Disparities in health care access based on various social determinants of health are ubiquitous in the USA. One such disparity, legal status, has been shown to significantly affect an individual's level of health care access, as well as their health outcomes (Durden and Hummer, Reference Durden and Hummer2006; DuBard and Massing, Reference DuBard and Massing2007; Pitkin Derose et al., Reference Pitkin Derose, Bahney, Lurie and Escarce2009; Khan et al., Reference Khan, Velazquez, O'Connor, Simon and De Groot2011; Vargas Bustamante et al., Reference Vargas Bustamante, Fang, Garza, Carter-Pokras, Wallace, Rizzo and Ortega2012; Edward, Reference Edward2014; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015). For example, undocumented immigrants utilise health services less frequently than native-born citizens or those with legal status and report worse experiences with and higher levels of discrimination within the health care system (Ortega et al., Reference Ortega, Fang, Perez, Rizzo, Carter-Pokras, Wallace and Gelberg2007; Jiménez-Rubio and Vall Castello, Reference Jiménez-Rubio and Vall Castello2020). Moreover, due to their lack of routine care, undocumented immigrants are more likely to use emergency departments as their primary point of contact with the health care system (Coustasse et al., Reference Coustasse, Lorden, Nemarugommula and Singh2009; Pitkin Derose et al., Reference Pitkin Derose, Bahney, Lurie and Escarce2009) and are more likely to arrive in the emergency department with late-stage conditions that could have been avoided with routine care (Footracer, Reference Footracer2009). These effects stretch beyond the undocumented immigrants themselves, as children of undocumented immigrants are less likely to receive both regular primary care and specialty care and have worse physical health outcomes (Adler and Rehkopf, Reference Adler and Rehkopf2008; Kannan and Veazie, Reference Kannan and Veazie2014; Oropesa et al., Reference Oropesa, Landale and Hillemeier2015; Gelatt, Reference Gelatt2016; Zamora et al., Reference Zamora, Kaul, Kirchhoff, Gwilliam, Jimenez, Morreall, Montenegro, Kinney and Fluchel2016; Vargas and Ybarra, Reference Vargas and Ybarra2017).

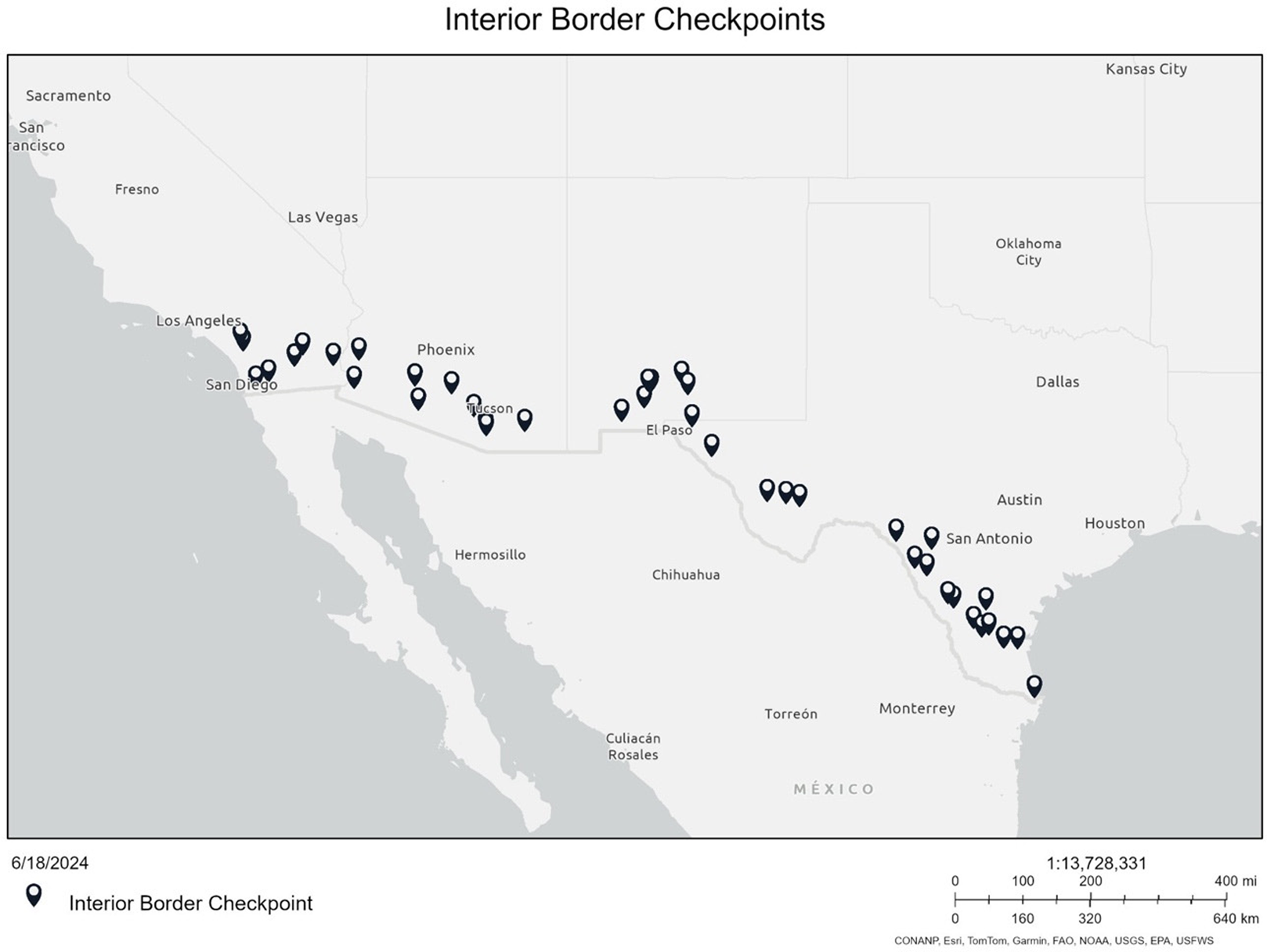

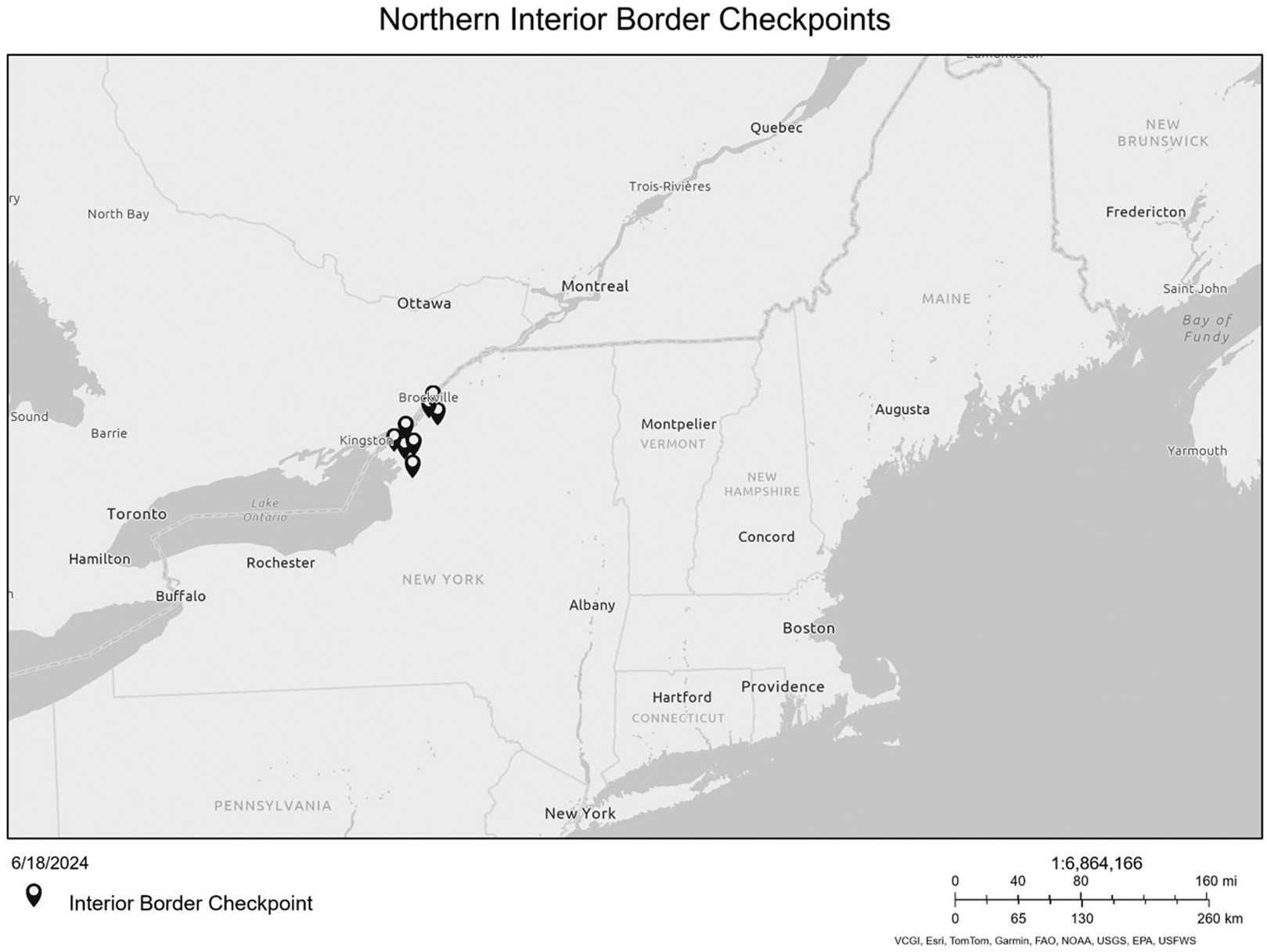

There are reasons to believe that immigration enforcement plays both a direct and indirect role in reducing health care access for undocumented immigrants. For one, such enforcement may decrease immigrants' trust in health care institutions (Cruz Nichols et al., Reference Cruz Nichols, LeBrón and Pedraza2018), and the trauma associated with immigration enforcement may also affect immigrants' mental health (Nichols et al., Reference Nichols, LeBrón and Pedraza2018), as well as the physical and mental health of their children (Brabeck and Xu Reference Brabeck and Xu2010; Zayas et al., Reference Zayas, Aguilar-Gaxiola, Yoon and Rey2015; Lopez et al., Reference Lopez, Kruger, Delva, Llanes, Ledón, Waller, Harner, Martinez, Sanders and Harner2017; LeBrón et al., Reference LeBrón, Schulz, Gamboa, Reyes, Viruell-Fuentes and Israel2018). Additionally, because immigration enforcement has been increasingly focused on interior areas of the USA, the threat of discovery outside of the immediate border region has been further expanded (Heyman et al., Reference Heyman, Núñez and Talavera2009; Bissonnette, Reference Bissonnette2022). One such form of interior immigration enforcement that may restrict health care access is interior border checkpoints (IBCs). These checkpoints, located in the interior of the USA within 25 and 100 miles of the border (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022), are in addition to the ports of entry along the borders between the USA and Mexico (Figure 1) and the USA and Canada (Figure 2). While there are 110 permanent checkpoints there are estimated to be about 170 IBCs, when temporary checkpoints are considered, and more than 50 million private and commercial vehicles pass through these IBCs every year (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022). IBCs draw their authority from the 1952 Immigration and Nationality Act that allows Border Patrol to conduct enforcement activities within a ‘reasonable’ distance of the border; defined as 100 air miles from any exterior boundary of the USA (Immigration and Nationality Act (NIA) of 1952). This authority was affirmed in United States v. Martinez-Fuerte (428 U.S. 543, 1976), in which the Supreme Court stated that the need for IBCs was great and the intrusion on Fourth Amendment rights was limited. When vehicles stop at IBCs, Border Patrol agents ask motorists if they are American citizens and maintain the legal authority to search any vehicle or individual if they have reasonable suspicion that any individuals in the vehicle may be undocumented or that the vehicle may be carrying illegal substances (Gonzales, Reference Gonzales2015). Between 2016 and 2020, Border Patrol agents apprehended 35,700 individuals at IBCs who were unable to produce appropriate documentation of legal status (U.S. Government Accountability Office, 2022). Once an individual is apprehended at an IBC, they are placed under arrest, and they begin the process of deportation from the USA.

Figure 1. Location of IBCs along the US southern border.

Notes: Figure shows IBCs along the US southern border with Mexico. Each marker indicates one checkpoint.

Figure 2. Location of IBCs along the US northern border.

Notes: Figure shows IBCs along the US northern border with Canada. Each marker indicates one checkpoint.

Due to their role in interior immigration enforcement, IBCs serve as an area of confinement for undocumented individuals living within the 100-mile border zone (Castañeda and Melo, Reference Castañeda and Melo2019; Boyce, Reference Boyce2024). IBCs can affect health outcomes for undocumented individuals because they often isolate undocumented immigrants and their families from health care services (Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Dodge, Reece, Schnarrs, Rhodes, Goncalves, Muñoz-Laboy, Malebranche, Van Der Pol and Nix2011; Castañeda and Melo, Reference Castañeda and Melo2019). Undocumented parents have reported having to decide between possible deportation and obtaining the medical care that they or their child needs when they are required to pass through an IBC to receive that care (American Civil Liberties Union, 2017; Lutz Reference Lutz2018). In 2018, to address the ways in which IBCs serve as a barrier to health care access, US Customs and Border Patrol (CBP) issued a memorandum that stated ambulances should not be delayed at IBCs (Alvarado, Reference Alvarado2018). This policy suggested that ambulances be expedited through IBCs so as not to delay care. However, the memorandum does not speak to individuals in private vehicles and does not negate the responsibility for Border Patrol agents to apprehend undocumented persons. In most cases, if an individual is determined to be undocumented at an IBC, a Border Patrol agent will accompany them to the hospital, wait at the hospital until they are medically cleared, and then place them under formal arrest (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Rico, Hernandez and Lee2024).

Due to the existence of IBCs, undocumented individuals throughout the border zone in the USA often must decide between receiving medical care and facing deportation or whether to forgo or delay care (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Rico, Hernandez and Lee2024). As interior immigration enforcement continues to become a higher political priority (Gurman, Reference Gurman2017), the US government has dedicated millions of dollars to expand IBCs along the border between the USA and Mexico (Gomez Jr, Reference Gomez2024). The expansion of IBCs along the southern border will further compound the challenges for undocumented individuals seeking to access necessary health care, but to date, there is limited research on how IBCs restrict the movement of undocumented individuals in the USA. Additionally, there is currently no assessment of how the American public views the effects of IBCs on access to health care services for undocumented immigrants.

This study aims to increase understanding of public opinion regarding IBCs as barriers to health care access, as well as perceptions of undocumented immigrants' right to health care access using a large (N = 6,178), national survey that contained an experiment assessing differences based on emergency vs non-emergency situations as well as age, gender, and pregnancy status of the undocumented immigrant. Below, we first provide additional background on the existing literature of US public opinion on undocumented immigrants as well as the hypotheses we derived based on this literature. We then provide a detailed introduction of our survey and its design, the data collected, and the variables utilised in our analyses.

We found that most Americans did not support arrest of undocumented immigrants prior to receiving emergency medical care and that they were less supportive regarding non-emergency care, although there were substantial differences based on respondent characteristics. We also found that most Americans supported arrest of undocumented immigrants after they received care and are released from the medical facility. Our analyses suggest that Americans generally support access to emergency medical care for all regardless of immigration status, supporting previous studies that show Americans are becoming increasingly pro-immigrant by providing context in which immigration enforcement is not supported. However, our findings here are more nuanced because immigrant demographics play an important role. Moreover, a majority of respondents were supportive of detention at some point in the care-seeking process or upon release which may ultimately deter undocumented immigrants from seeking care in the first place. We conclude by raising the question for future research of whether Americans only support maintaining access to care or if there is support for expanding access to care for undocumented immigrants.

1. Literature and theoretical expectations

As the number of immigrants in the USA has increased, so has the salience of immigration policy for the average American (Segovia and Defever, Reference Segovia and Defever2010; Mangum and Block Jr, Reference Mangum and Block2018). Most of the literature examining US public opinion towards immigrants, however, has analysed these attitudes through the framing of the ‘immigrant threat’ to ‘American’ culture or economics (Harell et al., Reference Harell, Soroka, Iyengar and Valentino2012; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014; Mangum and Block Jr, Reference Mangum and Block2018) and, to date, the literature related to US public opinion towards immigrants paints an inconsistent and often contradictory picture. For example, Americans express more negative attitudes towards immigrants if they believe that they will not follow American norms (Citrin et al., Reference Citrin, Green, Muste and Wong1997; Burns and Gimpel, Reference Burns and Gimpel2000; Hainmueller and Hopkins, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2014, Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015), but generally reject stereotypes of immigrants as threatening (Kulig et al., Reference Kulig, Graham, Cullen, Piquero and Haner2021) and tend to have more favourable attitudes towards them than populations of most European countries (Anderson and Turgeon, Reference Anderson, Turgeon, Anderson and Turgeon2022). Additionally, Americans are becoming increasingly pro-immigration (Wright and Levy, Reference Wright and Levy2020) even as belief in the US government's ability to address immigration issues has declined (Segovia and Defever, Reference Segovia and Defever2010). While US public opinion on immigrants has not been consistent over time (Wright and Levy, Reference Wright and Levy2020), given the recent focus on the US southern border and the increased number of undocumented immigrants entering the USA, issues related to undocumented immigrants are likely to only increase in relevance in US politics (Narea, Reference Narea2024). Indeed, there are some early indications that American public opinion may become more negative on the issue (Santhanam, Reference Santhanam2024).

While US public opinion may or may not be shifting, better understanding American perceptions as they related to health care for undocumented immigrants is a topic that is highly relevant for both academics and policymakers. For one, no matter how the American public feels about illegal immigration, there are well over 10 million undocumented immigrants currently in the USA who, at one point or another, will likely need to access medical care (Passel and Krogstad, Reference Passel and Krogstad2023). In many places, the increase in undocumented immigrants has led to substantial access and financial issues in the health care system (Gionet, Reference Gionet2024). Moreover, the topic will likely receive further attention with the US presidential election approaching (Narea, Reference Narea2024). Lastly, the conception that ‘health is different from other policy areas’ has been well established (Volden and Wiseman, Reference Volden and Wiseman2011; Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2012), making our work here an interesting test case whether it stretches to undocumented immigrants in the eye of Americans. While the specific topic of our analysis here has not been explored, the literature on US public opinion towards immigrants and immigration policy has identified many predictors that are relevant to this study.

1.1 Access to care

There are reasons to believe that most Americans support allowing individuals in need of medical care to access that care without obstructions, particularly in emergency situations. While the literature is scarce on the topic, it provides some evidence that broad US social norms favour guaranteeing access to medical care if individuals are in need (Haeder, Reference Haeder2019). Moreover, some states have begun to open their public assistance programs to immigrants (Nguyen, Reference Nguyen2023), and emergency programs have long been accessible at the local level (Haeder, Reference Haeder2010). This applies even to very conservative states like Texas (Dunkelberg, Reference Dunkelberg2016). Undocumented immigrants, under certain conditions, may also qualify for emergency coverage under Medicaid (Berlinger and Gusmano, Reference Berlinger and Gusmano2013). This general social norm towards ensuring at least some access under certain conditions is perhaps best exemplified by the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) which requires that hospitals participating in Medicare must provide screenings and stabilising treatment regardless of the patient's ability to pay (Lee, Reference Lee2004). Importantly, EMTALA provides this, albeit limited, access guarantee to all individuals regardless of citizenship and immigration status. Ultimately, it seems likely that most Americans would not support impeding care by detaining individuals prior to obtaining care, particularly emergency care. We thus hypothesise that respondents will be less supportive of detaining individuals for emergency conditions as compared to non-life threating conditions. Moreover, we hypothesise that respondents will be most supportive of detaining individuals at the time of release from medical care (as compared to all other potential times of detention).

1.2 Women and children

Perceptions of the immigrant's socially construction ‘deservingness’ may be a primary driver for whether people believe they should have access to health care (Schneider and Ingram, 1997, Reference Schneider and Ingram2005; Viladrich, Reference Viladrich2019). Generally, people express very little support for providing health care coverage to undocumented immigrants (Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Sanchez-Youngman, Murphy, Goodin, Santos and Burciaga Valdez2011), though there are higher levels of support for providing coverage to children of undocumented parents (Sanchez and Sanchez-Youngman, Reference Sanchez and Sanchez-Youngman2013). These findings are in line with broader assessments of the US welfare state in which children have long been the recipients of substantial benefits, particularly as compared to adult males (Haeder and Weimer, Reference Haeder and Weimer2015; Haeder et al., Reference Haeder, Sylvester and Callaghan2023). This applies, to a more limited degree, to women as compared to men, as well, particularly when they are pregnant (Skocpol, Reference Skocpol1995). Indeed, women and children are regarded as deserving but powerless and hence may become the recipients of certain benefits (Schneider and Ingram, 1997, Reference Schneider and Ingram2005). As a result, we expect that respondents will be least supportive of detaining individuals who are children or pregnant women respondents will be less supportive of detaining adult women over adult men.

1.3 Partisanship

Partisanship plays a central role in Americans' views of immigrants and immigration policy (Reich and Mendoza, Reference Reich and Mendoza2008; Knoll et al., Reference Knoll, Redlawsk and Sanborn2011; Merolla et al., Reference Merolla, Karthick Ramakrishnan and Haynes2013; Alamillo et al., Reference Alamillo, Haynes and Madrid2019) as well as health policy more generally (Bussing et al., Reference Bussing, Patton, Roberts and Treul2020; Jacobs and Mettler, Reference Jacobs and Mettler2020; Oberlander, Reference Oberlander2020; Sances and Clinton, Reference Sances and Clinton2021; Haeder and Chattopadhyay, Reference Haeder and Chattopadhyay2022; Wang Reference Wang2022; Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2023a). The divergence of immigration views along partisan lines has grown increasingly polarised over time (Baker and Edmonds, Reference Baker and Edmonds2021), though negative framing of immigrants has been shown to lead to support for more restrictive immigration policies among both Democrats and Republicans (Haynes et al., Reference Haynes, Merolla and Karthick Ramakrishnan2016). Additionally, an individual's political affiliation has been shown to be predictive of their attitudes towards immigrants (Chenane, Reference Chenane2022; Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng, Reference Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng2023; Sagir and Mockabee, Reference Sagir and Mockabee2023). Partisanship in views on immigration is maintained among Latino immigrant Republicans who have been found to view themselves as different than other Latinos and African Americans, do not believe racism is systemic, and generally minimise racist rhetoric from the Republican party (Cadena Jr, Reference Cadena2023). While there are nuances in the expression of negative attitudes towards immigrants among the US public, studies have consistently found that conservatives and Republicans are more likely to have anti-immigrant views than liberals and Democrats (Cadena Jr, Reference Cadena2023; Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng, Reference Dzordzormenyoh and Boateng2023; Willnat et al., Reference Willnat, Ogan and Shi2023). Based on the literature, we thus hypothesise that Democrats will be less supportive of detaining individuals than Republicans.

1.4 EducationFootnote 1

Several studies have highlighted the role that educational attainment may play regarding perceptions of immigrants (Espenshade and Calhoun, Reference Espenshade and Calhoun1993; Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2021), with more highly educated individuals having more favourable attitudes towards undocumented immigrants (Espenshade and Calhoun, Reference Espenshade and Calhoun1993). More highly educated individuals are also significantly more pro-immigrant overall (Haubert and Fussell, Reference Haubert and Fussell2006). Studies conducted in Europe show a similar relationship. For example, more years of schooling in Germany was associated with lower levels of concern about immigration and there were observed spillover effects related to maternal level of education (Margaryan et al., Reference Margaryan, Paul and Siedler2021). Another study, which examined attitudes towards immigrants and refugees across Europe, found that years of education was highly correlated with support for both groups (Abdelaaty and Steele, Reference Abdelaaty and Steele2022). Based on the literature, we hypothesise that individuals with higher levels of education will be least supportive of detaining individuals.

1.5 Sympathy towards immigrants

As described above, studies have shown that attitudes towards immigrants vary along several demographic factors including race, education level, and partisanship (Hopkins, Reference Hopkins2010; Mangum, Reference Mangum2019; Baker and Edmonds, Reference Baker and Edmonds2021; Macdonald, Reference Macdonald2021). In addition to assessing these individual predictors of public attitudes we also try to assess support and opposition to detaining immigrants based on their overall sentiment towards immigrants. Based on the literature, we hypothesise that those high in sympathy towards immigrants will be less supportive of detaining individuals than those low in sympathy.

1.6 Race and ethnicity

Lastly, race and ethnicity influence American attitudes towards immigrants (Espenshade and Calhoun, Reference Espenshade and Calhoun1993; Frasure-Yokley and Wilcox-Archuleta, Reference Frasure-Yokley and Wilcox-Archuleta2019), with white and native-born Americans showing greater support for restrictive immigration policies compared to non-white Americans and those who are foreign-born (Masuoka and Junn, Reference Masuoka and Junn2013; Mangum, Reference Mangum2019). Additionally, Hispanics/Latinos are more likely to have positive attitudes towards undocumented immigrants compared to non-Hispanic whites (Peña et al., Reference Peña, Verney, Devos, Venner and Sanchez2021) and other races and ethnicities (Espenshade and Calhoun, Reference Espenshade and Calhoun1993). Here, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders have been shown to be least likely to have positive view of undocumented immigrants (Frasure-Yokley and Wilcox-Archuleta, Reference Frasure-Yokley and Wilcox-Archuleta2019). Based on the literature related to the influence of race and ethnicity on attitudes towards immigrants, we hypothesise that Hispanics will be least supportive of detaining individuals under all conditions.

2. Data and methods

2.1 Data

To assess US public opinion related to the detention of undocumented immigrants seeking medical care we developed and administered an original survey in Qualtrics and utilised Lucid to recruit respondents. Respondents came from Lucid's large, online, opt-in panel and Lucid offered incentives to respondents. Lucid was compensated $1.50 per completed response. Lucid is considered a high-quality panel as its data have been validated and is frequently used for health services and policy work (Kennedy et al., Reference Kennedy, Mercer, Keeter, Hatley, McGeeney and Gimenez2016; Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019). Recent analyses identified Lucid as an exceptional forum for work related to social science and politics (Stagnaro et al., Reference Stagnaro, Druckman, Berinsky, Arechar, Willer and Rand2024). Overall, of the 10,327 US adults (18 years or older) who initiated the survey from 13 November to 19 November of 2023, 6,178 respondents completed it, with a completion rate of 60 per cent. Two standard attention checks, a crucial component to ensure data quality, were responsible for the attrition (Ternovsk et al., Reference Ternovsk, Orr, Aronow and Kalla2022). While the data collected approached national population benchmarks on gender, race, income, and education, we further improved fit by using weights based on the US Census Current Population Survey (for further details see Appendix Exhibits 1–6). This study was declared exempt by the appropriate Institutional Review Board.

2.2 Survey design and dependent variables

Our survey utilised an experimental approach to test differences in US public opinion based on differences in immigrant age, gender, and pregnancy status as well as whether the undocumented immigrant was seeking care for a medical emergency or a non-emergency. Initially, all respondents were introduced to the topic as follows:

Interior Border Checkpoints (IBCs) are places within the United States where Border Patrol requires all individuals passing through to provide evidence of citizenship or documentation of legal status in the United States. These checkpoints are located between 25 and 75 miles of the Mexico–United States border. IBCs have been set up to deter illegal immigration and smuggling activities along the southern border.

Think about the following scenario.

We then followed up with one of eight unique scenarios for each respondent. We developed these eight scenarios (four emergencies and four non-emergencies) utilising a man in his early thirties, a woman in her early thirties, a 5-year-old male child, and a woman in her early thirties who was pregnant. To make the scenarios more realistic, we also utilised four distinct names. These names were pre-tested in another survey to ensure that respondents identified them as Hispanic, in line with the characteristics of the primary migrant group in Texas, the southern border, and the USA. We utilised Emilio Perez (identified by 97.1 per cent of respondents as Hispanic in a previous survey), Luisa Diaz (94.0 per cent), Miguel Sanchez (94.1 per cent), and Alejandra Rodriguez (93.5 per cent) in order of the scenarios just described. The characteristics of the undocumented immigrants were mirrored between emergencies and non-emergencies. In the emergency condition, the undocumented immigrant's condition was described as follows:

[Name] just got into a severe car accident and suffered life-threatening injuries. An ambulance is taking [him/her] to the nearest emergency department.

This compares to the following non-emergency condition:

[Name] is on [his/her] way to a local clinic because [he/she] cut herself and needs stitches.

The two cases were based on real-world examples the researchers had identified in previous field work in the South Texas border region, again, seeking to describe realistic scenarios. After the introduction and the scenarios, respondents were asked whether they thought that the undocumented immigrant should be detained at four unique locations: (1) the Border Patrol IBC, (2) the medical facility prior to treatment,Footnote 2 (3) in the case of the emergency, when life-saving treatment was complete, but the patient was still recovering, and (4) at the time of release from the medical facility. For each of the four instances, we asked respondents whether they thought Border Patrol should detain the undocumented immigrant at that location, offering a standard 5-point scale from ‘Definitely not’ to ‘Definitely yes’, with a neutral mid-point option. The survey flow, complete scenarios, and question wording are contained in full in the Appendix. The survey and the hypotheses were pre-registered except for the hypotheses with regards to geography and education.

2.3 Independent variables

As described above, we were interested in various sub-analyses based on respondent characteristics. First, we determined the partisanship of the respondent by asking them the standard questions whether they ‘usually think of yourself as a Republican, a Democrat, an Independent, or what?’ We offered them three options for Democrats (strong, weak, lean), three options for Republicans (strong, weak, lean), and one Independent option. Four analyses, we then pooled the data into a Democratic, Independent, and Republican categories. Second, we asked respondents ‘how sympathetic would you say you are toward immigrants who are in the United States illegally’, offering them a 5-point scale from ‘Very unsympathetic’ to ‘Very sympathetic’, with a neutral midpoint option.Footnote 3 For analysis purposes, we then divided respondents into tertiles to increase the power of our analyses based on partisanship. We also created a binary indicator for whether respondents had obtained a college degree or higher. Lastly, we relied on respondent self-report race and ethnicity to determine which respondents were non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, non-Hispanic Asians, and Hispanics. By definition, all variables are binary indicators. These demographic data were provided directly from Lucid.

2.4 Methods

Due to the experimental design, our analyses below rely on two common methodological approaches. First, we relied on t-tests to make comparisons within respondents about the support for detaining undocumented immigrants at the four potential locations. Second, we estimated a series of weighted least squares (WLS) models utilising the aforementioned survey weights to make comparisons across respondents. These models serve as t-tests when utilising weighted regressions. We then relied on comparisons of predicted means to assess statistical differences (Cameron and Trivedi, Reference Cameron and Trivedi2010; Long and Freese, Reference Long and Freese2014). We assessed differences in various sub-analyses (such as partisanship or southern residency) by interacting indicator variables for each treatment with the respective variable. We note that we resorted to WLS estimation over ordered logit models to facilitate comparisons, interpretation, and presentation of results, as is a common approach. We then compared differences using mlincom in Stata (Long and Freese, Reference Long and Freese2014) and considered a p-value lower than 0.05 as statistically significant throughout our analyses.

3. Results

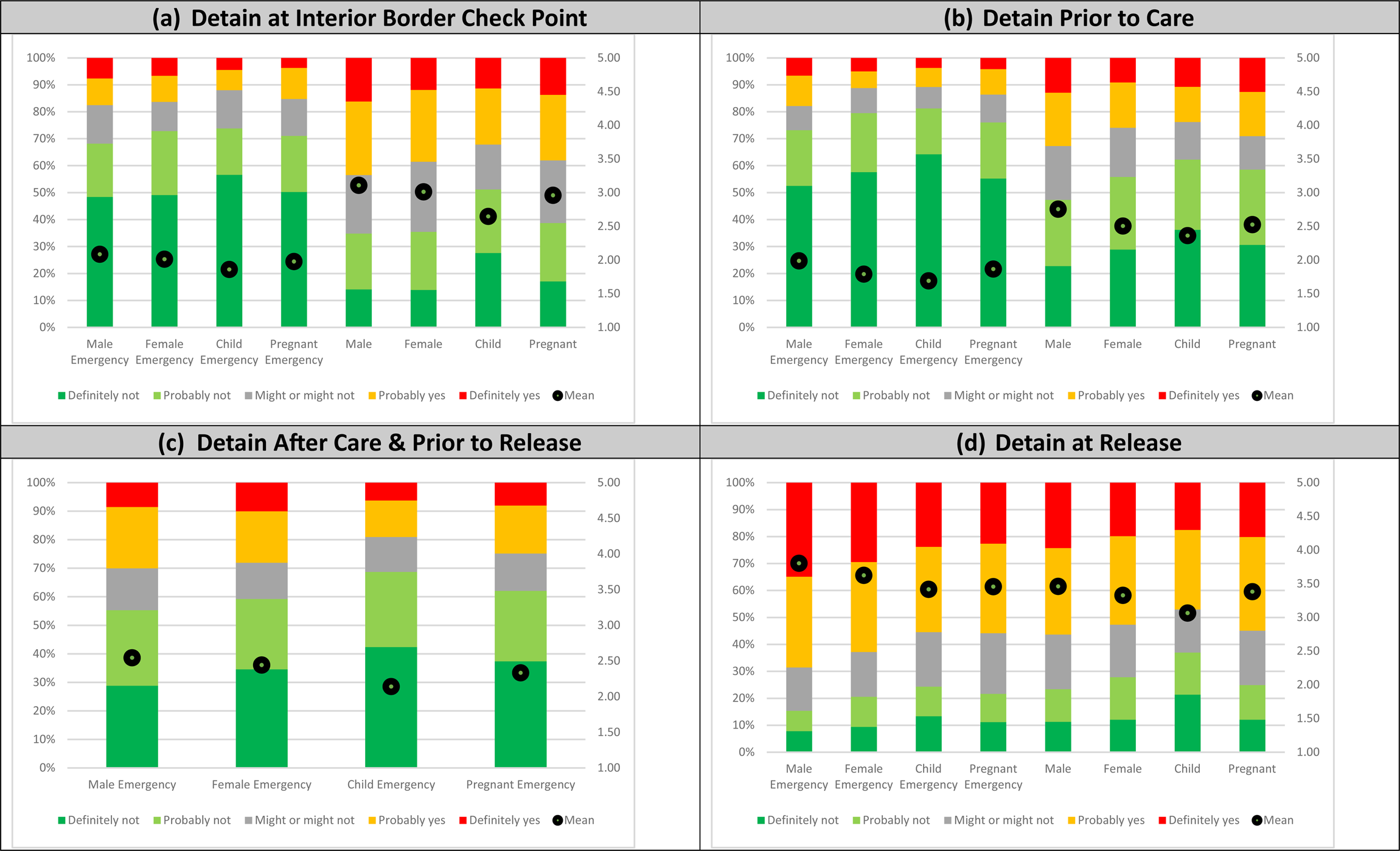

Our unadjusted results are presented in Figure 3. Several observations stand out. First, roughly 60 per cent of respondents favoured not detaining individuals presenting with emergency conditions at the first three potential points of detention (Figures 3a–c). In eight of the 12 potential cases, the opposition to detaining individuals even exceeded 70 per cent. Contrastingly, between 11 and 30 per cent of respondents favoured detaining individuals in emergency situations, including in situations where the individual had not received treatment yet. At the same time, after treatment was complete (Figure 3d), between 15 and 24 per cent of respondents opposed detention, whereas 55–69 per cent favoured detention.

Figure 3. Distribution and mean of responses whether respondents favour detaining undocumented immigrants: (a) detain at IBC, (b) detain prior to care, (c) detain after care and prior to release, and (d) detain at release.

Notes: Based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording in the Appendix.

The findings were much more mixed for non-emergencies, particularly at the IBC itself (Figure 3a), where between 35 and 51 per cent opposed detention and between 32 and 44 per cent favoured detention. At the clinic prior to treatment (Figure 3b), between 47 and 62 per cent of respondents opposed detention whereas 24 to 33 per cent favoured it. Also noticeable was the fact that more than 50 per cent of respondents favoured detaining the individual at the time of release post-treatment (Figure 3d) with the only exception being the child in a non-emergency (47 per cent) while only 23–37 per cent opposed it.

3.1 Emergencies vs non-emergencies

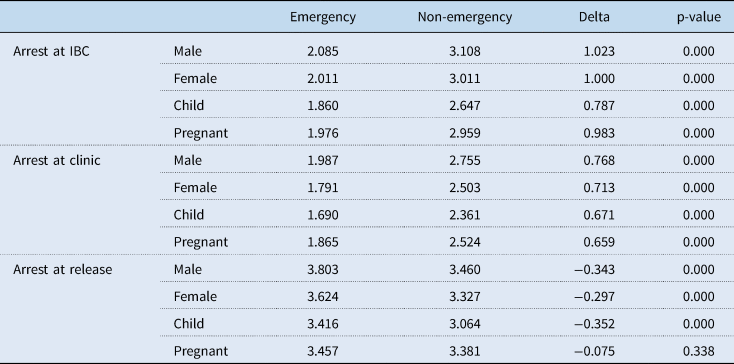

Across all respondents, we found our hypothesis related to the comparison between emergency and non-emergency conditions partially confirmed (Table 1). That is, respondents consistently were less supportive of detaining individuals suffering an emergency (life-threatening car accident) that a non-emergency (needing stitches) for detention at the interior border checkpoint (deltas: 0.787–1.023, p-values <0.001) and at the medical facility prior to treatment (deltas: 0.659–0.768, p-values <0.001). At these two locations, differences were significant for all four scenarios (male, female, child, pregnant female). However, at the third potential point of arrest, release after treatment, respondents were more supportive of detaining those with medical emergencies (deltas: 0.297–0.343, p-values <0.001) with the exception of pregnant women. Importantly, these findings were consistent for both Democrats (see Appendix Exhibit 7) and Republicans (see Appendix Exhibit 8), those with low (see Appendix Exhibit 9) and high sympathies (see Appendix Exhibit 10) towards immigrants, and for whites (see Appendix Exhibit 11), Blacks (see Appendix Exhibit 12), and Hispanics (see Appendix Exhibit 13). However, findings for Asian respondents were inconsistent (see Appendix Exhibit 14). Here, we found no statistically significant differences for women, children, and pregnant women at the time of release from treatment. Lastly, the findings were also analogous for those with (see Appendix Exhibit 15) and without a college degree (see Appendix Exhibit 16). We note that the p-values are consistently low and remained statistically significant even with substantial Bonferroni adjustments.

Table 1. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, emergency vs. non-emergency

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

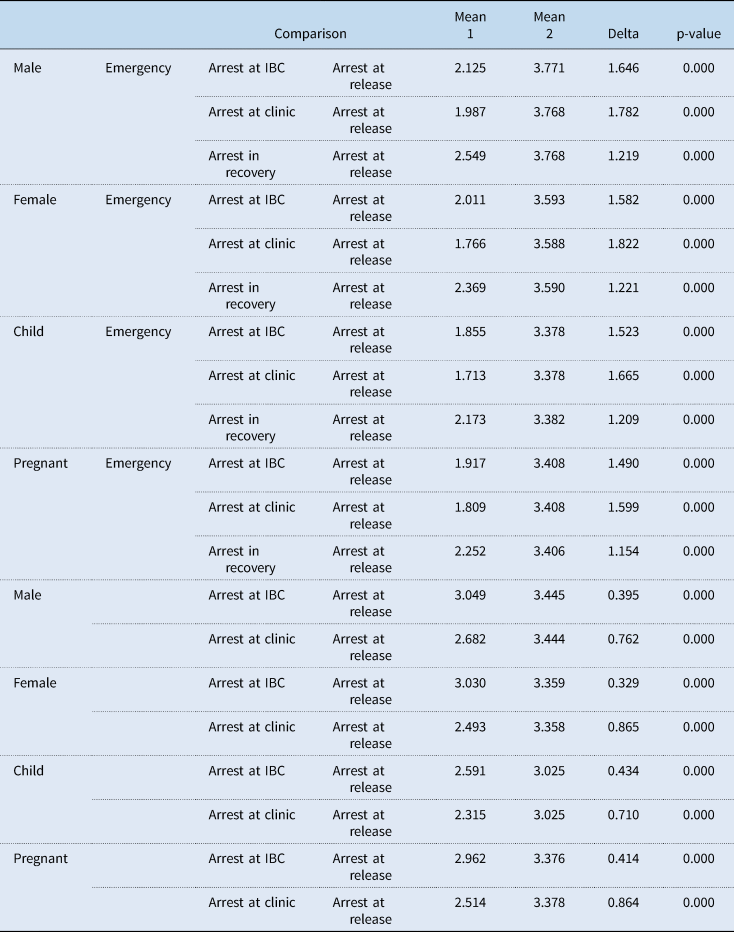

3.2 Location of detention

We found consistent evidence that respondents were most supportive of detaining undocumented immigrants at the time of release from care as compared to all other potential points of detention for both emergencies and non-emergencies as well as for all four scenarios (Table 2). For men, the differences ranged from 1.219 (p < 0.001) to 1.646 (p < 0.001) in emergencies and 0.395 to 0.762 (p < 0.001) in non-emergencies; for women the differences ranged from 1.221 (p < 0.001) to 1.822 (p < 0.001) in emergencies and 0.329 to 0.865 (p < 0.001) in non-emergencies, for children the differences ranged from 1.209 (p < 0.001) to 1.665 (p < 0.001) in emergencies and 0.434 to 0.710 (p < 0.001) in non-emergencies, and for pregnant women the differences ranged from 1.154 (p < 0.001) to 1.599 (p < 0.001) in emergencies and 0.414 to 0.864 (p < 0.001) in non-emergencies. These differences held across partisans (see Appendix Exhibits 17 and 18), for those with low and high levels of sympathies for immigrants (see Appendix Exhibits 19 and 20), and across racial and ethnic groups (see Appendix Exhibits 21–24). Differences held consistently those with (see Appendix Exhibit 25) and without a college degree (see Appendix Exhibit 26).

Table 2. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, by location of detention

Notes: T-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

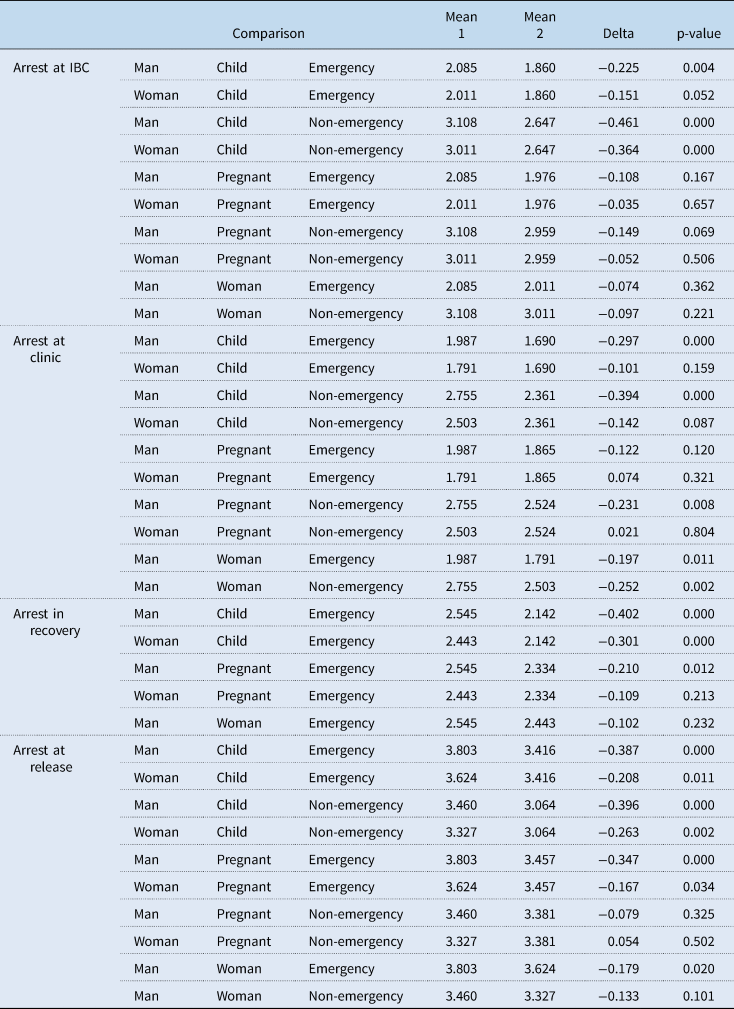

3.3 Women and children

Our findings related to differences based on the four scenarios (male, female, child, pregnant female) and different social constructions were more nuanced (Table 3). The only consistent finding that emerged was for differences between the adult man and the child in both emergency (deltas across detention points: 0.225–0.402, p-values <0.005) and non-emergency conditions (deltas across detention points: 0.394–0.461, p-values <0.001). We also identified consistent differences between men and the three other groups under the emergency scenario at the time of release (deltas: 0.179–0.387, p-values <0.021) and women and the two other groups under the emergency scenario at the time of release (deltas: 0.167–0.208, p-values <0.035). These findings are consistent for both Democrats (see Appendix Exhibit 27) and Republicans (see Appendix Exhibit 28) as well as those with low (see Appendix Exhibit 29) and high levels (see Appendix Exhibit 30) of sympathy for immigrants. However, we identified substantial differences in the pattern based on the race and the ethnicity of the respondent. That is, while we found analogous patterns for White respondents (see Appendix Exhibit 31), we only identified differences between adult males and children in non-emergency conditions for Hispanics (see Appendix Exhibit 32) and we identified no differences for both Blacks (see Appendix Exhibit 33) and Asians (see Appendix Exhibit 34). Differences for those with (see Appendix Exhibit 35) and without college degrees (see Appendix Exhibit 36), by-and-large mirrored, those for all respondents.

Table 3. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, by immigrant characteristics

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

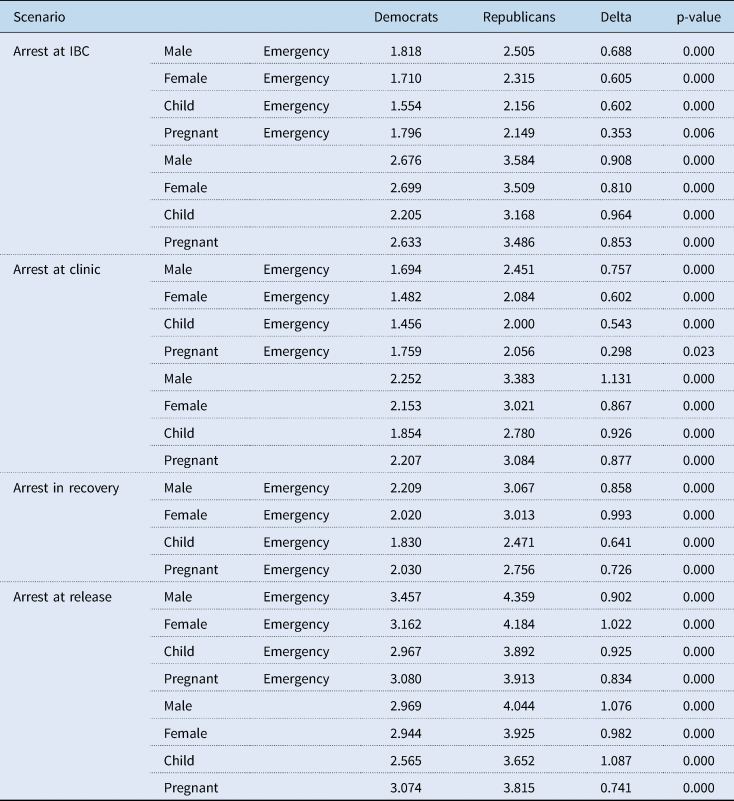

3.4 Partisanship

Our assessment of differences based on respondent partisanship (Table 4) indicated consistent and often substantial differences between Democrats and Republicans (deltas: 0.298–1.131, p-values <0.024). These differences were present at all four potential locations of detention as well as for both emergency and non-emergency situations. Differences were smallest for the detention of pregnant women in emergency situation at the medical facility prior to treatment (delta: 0.298, p-value <0.024) and at the IBC (delta: 0.353, p-value <0.007); they were largest for men in non-emergencies at the medical facility prior to treatment (delta: 1.131, p-value <0.001) and at the time of release (delta: 1.076, p-value <0.001).

Table 4. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, by partisanship

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

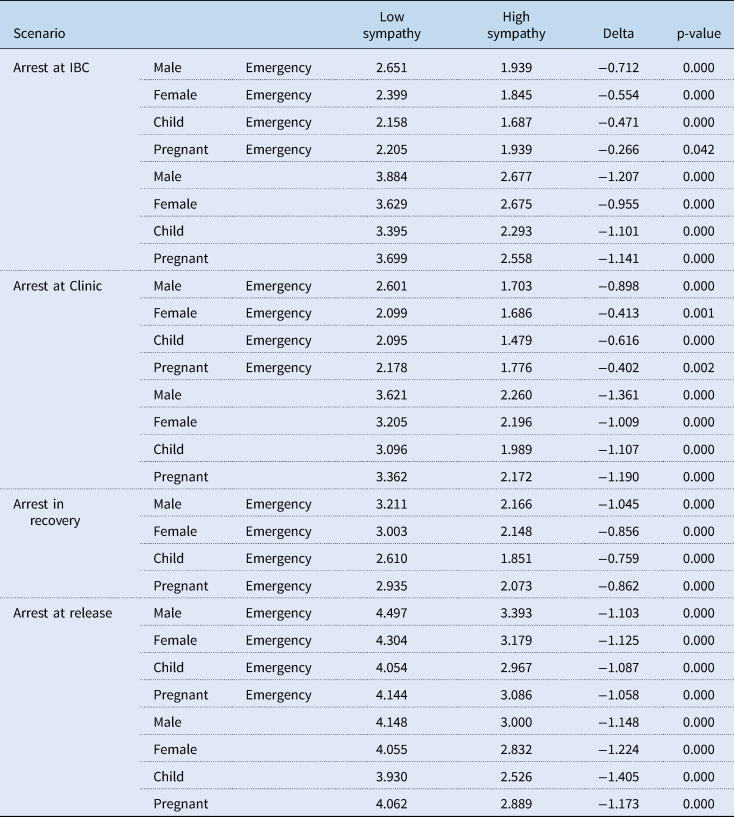

3.5 Sympathy towards immigrants

Similarly, we also found consistent differences comparing individuals low in sympathy to those high in sympathy (Table 5) for all cases ranging from a low of 0.266 (p-value <0.043) for detaining a pregnant woman at the IBC and 0.402 (p-value <0.003) at the facility prior to treatment in an emergency situation to a high of 1.361 (p-value <0.001) for a male in a non-emergency situation at the facility prior to treatment and 1.405 (p-value <0.001) for a child in a non-emergency situation at the time of release.

Table 5. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, by sympathy for undocumented immigrants

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

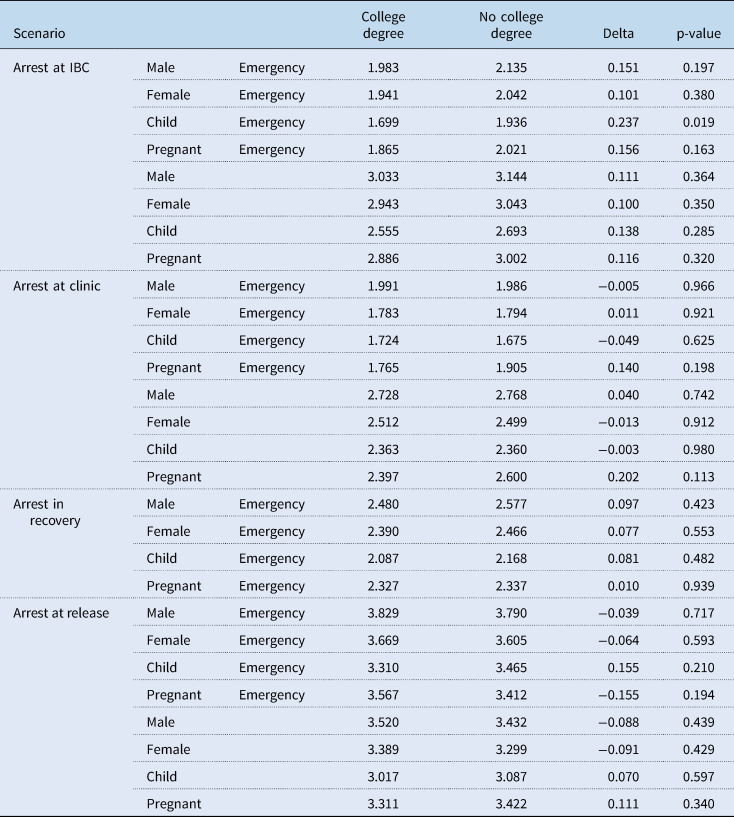

3.6 Education

We only found differences based on education (Table 6) in the case of children in emergency situations at the IBC (delta: 0.237, p-value <0.020) with those without a college degree more likely to favour detention. Both comparisons tended to be smaller than those based on partisanship or attitudes towards immigrants.

Table 6. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, by education level

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix.

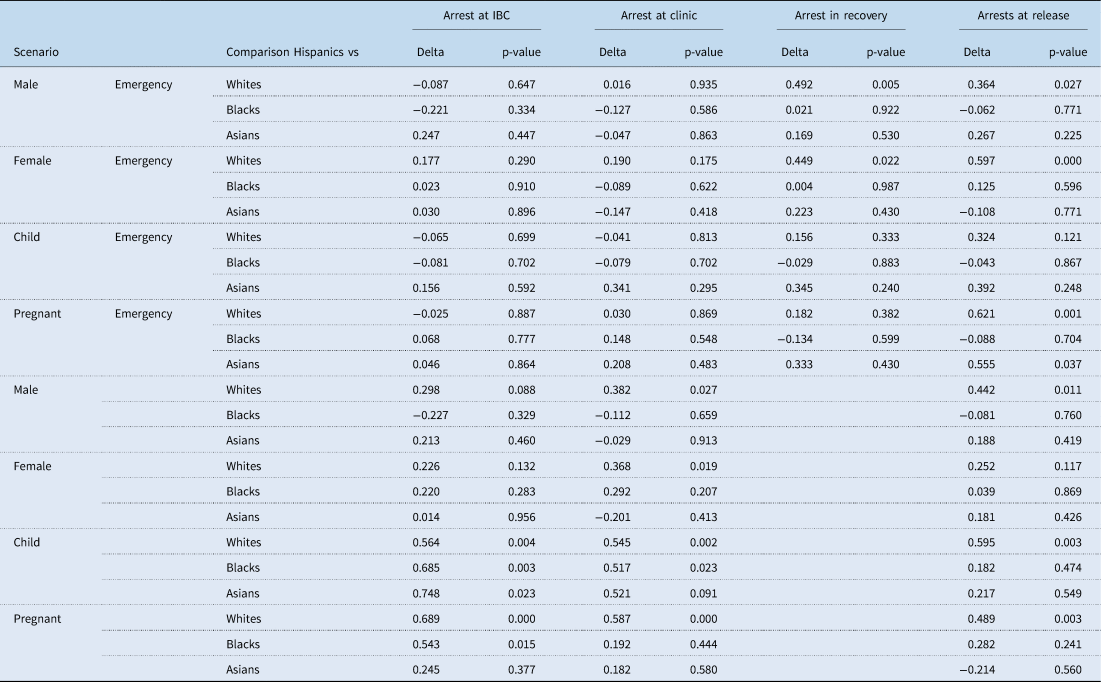

3.7 Race and ethnicity

Lastly, comparing Hispanics to whites, Blacks, and Asians we only found very few instances where differences were statistically significant (Table 7). In all cases, Hispanic respondents were less supportive of detention. For non-emergency conditions, we found that Hispanic respondents were consistently less supportive of arrests than whites for both children (0.54–0.59, p-values <0.005) and pregnant women (0.49–0.69, p-values <0.004). Hispanics were also less supportive of arrest for men at clinics (0.37, p-value <0.028) and at release (0.59, p-value <0.004) and women at clinics (0.37, p-value <0.020). At the same time, Hispanics were also less supportive of arrests than Blacks for children at the IBC (0.68, p-value <0.004), and the clinic (0.52, p-value <0.024) and for pregnant women at the IBC (0.54, p-value <0.016). We identified even fewer differences for emergency conditions. Here, differences between Hispanics and whites were significant for both women and men in recovery (men: 0.49, p-value <0.006; women: 0.45, p-value <0.023) and at release (men: 0.36, p-value <0.028; women: 0.60, p-value <0.001) and for pregnant women at release (0.62, p-value <0.002).

Table 7. Comparison of support for detaining undocumented immigrants, Hispanics vs other races/ethnicities

Notes: Weighted t-tests based on authors’ survey of 6,178 respondents completed from 13 November to 19 November of 2023. Survey flow and questions wording are given in the Appendix. Coefficients are omitted for clarity.

4. Discussion and conclusion

We administered a national survey assessing US public opinion towards detention of undocumented immigrants seeking medical care that required passage through an IBC for emergency and non-emergency conditions at four distinct points in the care-seeking process. To our knowledge, this analysis is the first assessment of such attitudes. We found that most respondents were not supportive of detaining individuals at IBCs or medical facilities in emergency scenarios regardless of characteristics of the care-seeking individual (man, woman, pregnant woman, child). This finding was consistent across all respondent demographics analysed here. However, this changed after medical treatment was complete, a finding that was once again consistent across respondent characteristics. We also found that respondents were generally more sympathetic towards children and pregnant women compared to women and men although these findings were inconsistent for Hispanics, Blacks, and Asians. Moreover, partisanship and sympathy expressed towards immigrants influences attitudes towards detention with respondents who identified as Republican and those who expressed low sympathy towards immigrants consistently showing higher levels of support for detention in each scenario and for all characteristics of the care-seeking individual. This is consistent with the literature, which finds that those identifying as Republicans or conservative have more negative attitudes towards immigrants and tend to support more restrictive immigration policy. Findings based on race and ethnicity showed more inconsistencies. If at all, Hispanics tended to more sympathetic and opposed to the detaining care seekers. We also found that respondents without a college degree expressed higher levels of support for detaining children in emergency scenarios at IBCs. This finding is consistent with the literature that shows that higher levels of education are associated with more pro-immigrant attitudes.

Findings from this study support and expand the knowledge base regarding American attitudes towards immigrants. Previous studies show that Americans are becoming increasingly pro-immigrant and often reject stereotypes of immigrants as threatening, and our findings demonstrate overall support for forgoing immigration enforcement prior to the administration of necessary medical care (Wright and Levy, Reference Wright and Levy2020; Kulig et al., Reference Kulig, Graham, Cullen, Piquero and Haner2021). While there are notable differences based on respondent characteristics, our findings expand the current literature by providing context in which typical immigration enforcement is not supported. Moreover, we extend the findings related to social construction to the analysis of undocumented immigrants and medical access. Our findings, with important nuances, indicate that while Americans generally support the provision of medical care, a majority nonetheless favours ultimate detention. It is worth noting that a small but substantial minority of Americans favours detaining undocumented immigrants even in life-threatening situation.

Several limitations apply to our study. First, our survey is cross-sectional providing a one-time assessment of the topic. As a result, all commonly acknowledged limitations related to this type of research apply. We also note that anti-immigrant rhetoric during the presidential campaign may further alter public opinion on the issue, something that can only be captured via a panel survey approach. Moreover, our analysis makes use of an online, non-probability sample platform, as is common practice in survey research today. Weighting and attention checks provide some mitigation of concerns, as well as the fact that the majority of our analyses focus on experimental designs. Importantly, the survey data used has been validated, is frequently used for this type of work, and is considered to be of high quality (Coppock and McClellan, Reference Coppock and McClellan2019; Haeder et al., Reference Haeder, Sylvester and Callaghan2021, Reference Haeder, Sylvester and Callaghan2023; Haeder and Chattopadhyay, Reference Haeder and Chattopadhyay2022; Haeder and Moynihan, Reference Haeder and Moynihan2023b). Third, we focus on only one ethnic group in our analyses, Hispanics. While this is the most common migrant group, we cannot speak to public sentiments about other groups. Analogously, our experiments relied on certain characteristics and circumstances. While these were chosen strategically, we cannot guarantee that our findings hold in other cases. Moreover, utilising these concrete scenarios may overstate public support compared to cases where questions would have been asked in the abstract. Moreover, our scenarios are relatively short albeit strategically developed to raise the salience of certain items. However, more intensive treatments and interventions may have shown substantially different effects.

Overall, our findings suggest that most of the American public believe that IBCs should not act as immediate barriers to receiving medical care for undocumented immigrants, especially in emergency situations and for children and pregnant women. Moreover, Americans seem to favour the completion of treatment. However, as described there are important differences based on respondent characteristics, and, at times, these differences can be quite substantial. Currently, however, detention of undocumented immigrants at IBCs while travelling for medical care, even when the care is lifesaving, occurs, particularly when travelling in private vehicles (Lutz, Reference Lutz2018). While US CBP policy advocates for the unrestricted passage of ambulances through IBCs (Buch, Reference Buch2018), no such policy exists for individuals travelling in private vehicles. Our findings also suggest that there may be public support for expanding existing federal policies to allow for undocumented individuals to pass through IBCs to access medical care. Policy expansion may take the form of including private vehicles in the current US CBP policy regarding ambulance passage through IBCs. Such changes may increase health care access for some undocumented immigrants living between the border and IBCs without negating Border Patrol's responsibility to apprehend those without legal status. However, at the same time, our findings raise several concerns in overcoming the substantial barriers that immigration enforcement poses for access to care both for undocumented immigrants and family members, many of which may be US citizens. The findings that a majority of Americans favour detention may create a barrier that may be too large to overcome except perhaps in life-threatening emergencies. It is well established that undocumented immigrants may often avoid reaching out to public services like 911 for fear of interacting with law enforcement and immigration officers, thus making private transportation an importance pathway to care. These findings also support the current Border Patrol policies of accompanying those found to be undocumented from the IBC to the hospital and detaining them after treatment (U.S. Customs and Border Protection, 2015). Ultimately, reducing health disparities will likely require a more comprehensive policy adjustment that fully exempts travel for health-related reasons from subject to detention. Whether this change is politically feasible remains to be explored.

Of course, knowing that they may ultimately be arrested, even after treatment, may further dampen immigrants' incentive to seek care, even when severely needed and even when they know they will not be detained prior to seeking care. Importantly, this may also apply to care for the children of undocumented immigrants, whether they are US citizens or not. Delay and avoidance of care because of legal status contributes to worse health outcomes for undocumented immigrants compared to native-born Americans or those with legal status in the USA (Footracer, Reference Footracer2009; Vargas Bustamante et al., Reference Vargas Bustamante, Fang, Garza, Carter-Pokras, Wallace, Rizzo and Ortega2012; Edward, Reference Edward2014; Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Boyce, Reference Boyce2024). Such outcomes include untreated health conditions, low immunisation rates, and chronic conditions such as hypertension and cardiovascular disease (Hacker et al., Reference Hacker, Anies, Folb and Zallman2015; Martinez et al., Reference Martinez, Wu, Sandfort, Dodge, Carballo-Dieguez, Pinto, Rhodes, Moya and Chavez-Baray2015). While our findings show that most respondents do not support detention prior to the completion of medical care, especially in emergency scenarios, the majority do support arrest upon release from the medical facility. This finding demonstrates that most Americans support the standard practice on this topic, which is for Border Patrol to accompany the undocumented individual upon discovery of their legal status at an IBC, allow them to complete care, and then detain them (Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, Rico, Hernandez and Lee2024). The threat of arrest and detention upon completion of medical care, however, likely contributes to health care delays and avoidance among undocumented immigrants in the USA, as the ultimate outcome may still be possible deportation. Ultimately, our findings here also raise questions about the role that health care personnel should and want to play when it comes to immigration enforcement.

Given the increasing salience and polarisation of immigration policy at both the federal and state level, examining American's attitudes towards interior immigration enforcement is central to contextualising immigration policies, health-related or otherwise. Our findings suggest that the national value of emergency health care access for all holds true for undocumented immigrants as well as US citizens and those legally present in the USA. Further study is needed to understand the full scope and nuance of US public opinion of undocumented immigrants' rights to health care and medical care access and the extent to which interior immigration enforcement should be applied in the health care context. One particularly interesting topic for future enquiry is whether and under what conditions public attitudes about the topic may shift. Questions also emerge whether Americans will differentiate between ensuring merely access to care or whether they are willing to expand access, at least for ‘deserving’ groups like children and pregnant women to health coverage. At the same time, a number of interventions seeking to improve access to care for undocumented immigrants and their families such as mobile clinics remained unassessed. More broadly, public attitudes providing broader access to care in the form of insurance coverage also remain underexplored. Lastly, the question of whether and how policymakers may be punished or rewarded by their constituencies based on their willingness to improve access to medical care deserves further scholarly attention. Ultimately, better understanding public perceptions about immigrants' access to care holds important relevance and substantial implications for US politics.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744133124000252.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the reviewers and editors for their helpful suggestions.

Financial support

No outside support was obtained to support this work.

Competing interests

None.