In rural Philippines, promising students were given financial support to pursue further education outside their village (Rubin Reference Rubin2018, 166). In the region that later became Eritrea, more than 33,000 women learned to read during the “Illiteracy is our main enemy” campaign (Gottesman Reference Gottesman1998; Pateman Reference Pateman1998). In Nepal, judges travelled to rural villages as a “mobile team” to consult with victims prior to trial in cases of domestic violence against women (Braithwaite Reference Braithwaite2015, 12). In mid-March 2020, a public health campaign in north-western Syria aimed to prevent the spread of COVID-19 (Furlan Reference Furlan2020). In none of these cases were these programs and services provided by the state. Instead, the New People’s Army (the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines), the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, the Communist Party of Nepal–Maoists, and the Syrian Salvation Government (the governance arm of Hayat Tahrir al-Sham), respectively, spearheaded these efforts. In short, rebel organizations, perhaps best known for their violence, provided basic goods and services and worked to meet the needs of citizens.

The provision of public services such as education, health, and dispute-resolution mechanisms are typically thought to be the purview of state governments. Nevertheless, empirically, non-governmental organizations, religious groups, criminal syndicates, and rebel groups all participate, to some extent, in these core components of governance. In the context of armed conflict, rebel groups stand out as being one of the most prominent non-state actors to participate in these behaviors. Research on governance by rebel groups during civil wars has drawn our attention to the ways in which armed non-state actors govern as a direct component of their challenge to the state (e.g., Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Arjona, Kasfir, and Mampilly Reference Arjona, Kasfir and Mampilly2015; Cunningham and Loyle Reference Cunningham and Loyle2021; Huang Reference Huang2016a; Kasfir, Terpstra, and Frerks Reference Kasfir, Frerks and Terpstra2017; Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011; Staniland Reference Staniland2014). This observation highlights a critical need to understand how, when, and why rebels take up governance functions; how they interact with the state and other providers as they do so; and the outcomes of such efforts for the welfare of ordinary citizens.

Rebel groups are organized non-state actors that challenge their host state through violent means in order to achieve a political objective. We center our attention on rebel groups as consequential actors in the global system in their own right; with violent conflicts within states continuing around the world, rebels demonstrate complex relationships with states, external supporters and adversaries, international organizations, other rebel actors, and civilian populations. We focus on rebel actors because of the inherently political nature of their governance claims as a direct challenge to state power.

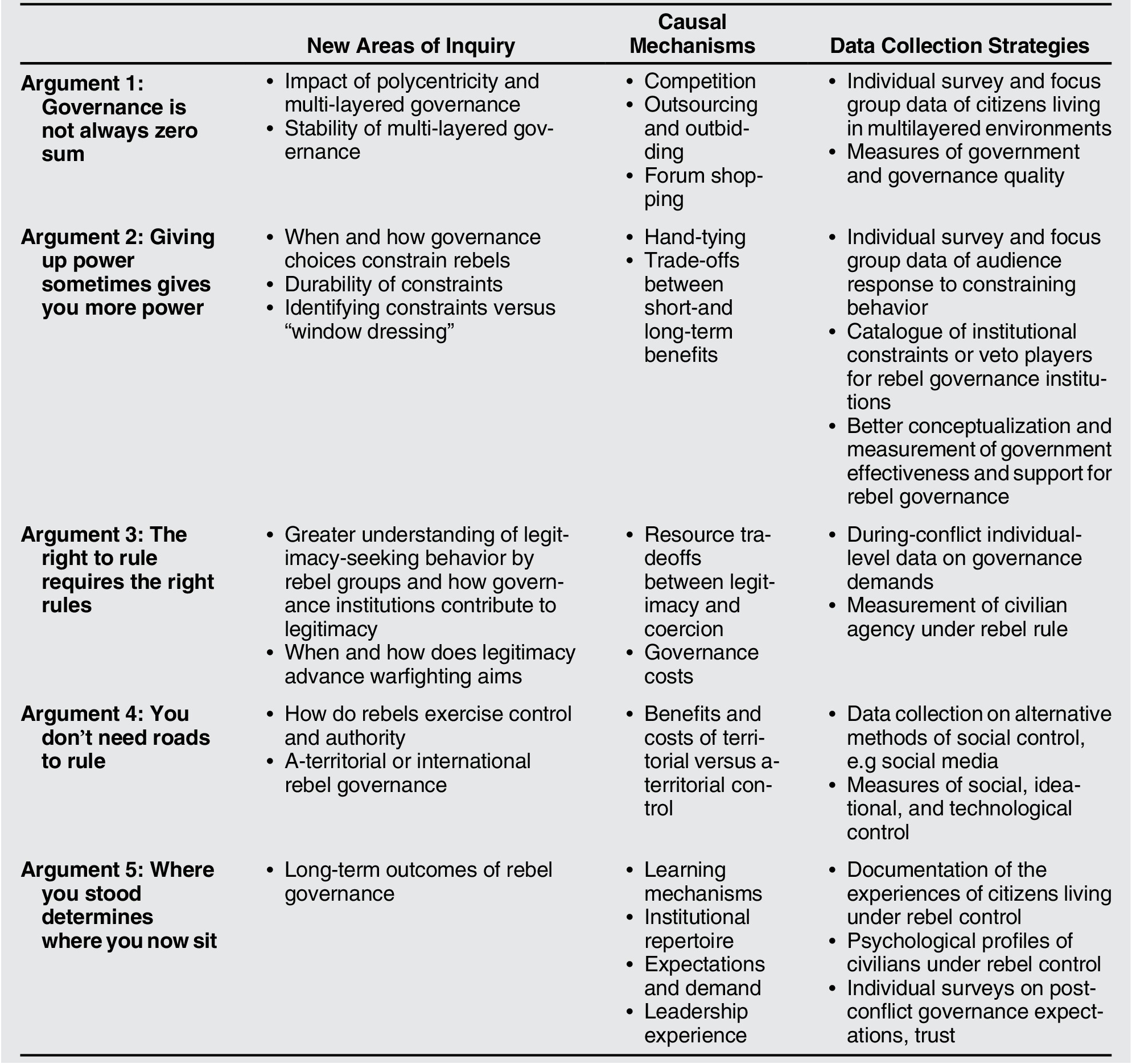

In this article, we evaluate existing work on rebel governance, illuminating key contributions and building a bridge to scholarship on governance more broadly. To do so, we develop five arguments, each of which challenges common assumptions and understandings about rebel governance and offers new ways to conceptualize, theorize, measure, and analyze rebel governance. Our arguments, in brief, are as follows. First, rebel governance is not always zero-sum. Rather, it is often characterized by overlapping zones of control and even collaborative efforts by a variety of actors. Second, we argue that one way rebel groups amass more power is by giving up power, or more specifically, by creating institutions that tie their own hands. Institutions such as popular elections and referenda create risks for rebel groups, and yet they yield enough political benefits that many rebel groups choose to implement them. Third, it has become almost a truism that rebel groups seek legitimacy, and yet we identify reasons to further probe even this basic assumption. Rebel governance can boost legitimacy but can also jeopardize it, depending on civilian responses and other factors. Fourth, rebels can wield control over civilians without holding territory and govern without infrastructure. This is a departure from conventional understandings and yet, once freed of the territorial control assumption, significant theoretical and empirical room opens up for further research into rebel governance via a-territorial means. Finally, we contend that rebel governance has enduring impacts on societies, civilians, and state governance, and identify new ways to examine such impacts.

While these arguments are not centered on a single theme, they each address an area of key debate or a nascent research agenda that yields critical questions. We do not call for a paradigm shift in the study of rebel governance; instead, we advocate for a pluralistic approach moving forward, relaxing problematic assumptions in the existing literature and advancing a multifaceted exploration of new questions—involving new levels of analysis, actors, and scope conditions. In developing our five arguments, we pay particular attention to how new cases and methods can be brought to bear to explore novel questions and motivate innovative research agendas.

The study of rebel governance has important implications for the study of governance more broadly. In deepening our understanding of rebel governance, we gain new insights into why non-state actors provide goods and services and how non-state governance differs, whether in motivation, processes, or outcomes, from state governance. Research into rebel governance also has potential to yield new insights about the strategic use of governance by both states and non-state actors, the relationship between governance and local legitimacy, the relevance of territorial control for governance provision, and the effects of institutional design on governance outcomes. These issues are relevant for other governance providers, including NGOs, international NGOs, and corporations, all of which play a role in delivering basic services to communities around the world. A greater understanding of how and why armed non-state actors govern will advance the growing literature on types and styles of governance in a diversity of contexts.

Argument 1: Governance Is Not Always Zero-Sum

Foundational work in the field of rebel governance has focused almost exclusively on emblematic cases of well-organized and highly structured rebel institutions (e.g., Arjona Reference Arjona2016; Kasfir Reference Kasfir2005; Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011). Given this focus, cases such as the NRM in Uganda, the LTTE in Sri Lanka, and the self-declared Republic of Somaliland have come to dominate our understanding of how rebel groups solidify legitimacy and control. In many ways, this work has replicated the state governance literature in looking for those rebel groups whose governance activities and outcomes most closely resembled that of states, achieving a maximalist conception of governance and control. We question the generalizability of findings from these cases. In particular, we challenge the utility of this maximalist conception by studying areas of multi-layered governance.

Exclusively studying strong and well-established governance structures by rebel groups has led to an overfocus on the “state-like” qualities of rebel governance (or lack thereof). Yet work on early state formation did not begin with the premise that rebels sought to resemble, imitate, or be states per se. Instead, the territorially defined sovereign state was seen as the project of a confluence of factors, from geo-political competition (Ertman Reference Ertman1997) to the rise of literacy and decline of religiosity (Anderson Reference Anderson1983). Of particular note, the period of Western state formation was characterized by diverse sets of actors with often overlapping areas of authority (Spruyt Reference Spruyt1996). A laser focus on the most “state-like” rebels belies the diversity of actors and governance behaviors at play in conflict settings, and critically, limits the bounds of our collective inquiry about governance.

Implicit in many studies of armed conflict is the assumption that rebels and the government are engaged in a zero-sum conflict over governance (Ledwidge Reference Ledwidge2017), yet this need not be the case. The focal cases in the study of rebel governance reinforce this assumption through an emphasis on groups that maintain absolute authority in a particular territory. Given the variety of possible governance-providing actors, and the array of possible governing arrangements, we find the assumption of a single governing authority to be myopic, precluding many important questions.

If governance is creating order and shaping behavior (Weber Reference Weber, Gerth and Mills1946), governance need not come from the state or from any single actor. In addition to the state, security and the provision of goods and services can come from armed actors, such as rebel groups or criminal syndicates (e.g., Lessing Reference Lessing2020), non-state actors such as NGOs or religious organizations, or even other states. Given the range of actors potentially involved in governance, the quest for governance need not be zero-sum. Rather, there are likely competing and complementary sources of authority, legitimacy, and capacity within a given space and time (Ostrom Reference Ostrom1990).

Individuals around the world live in a variety of governance contexts. On one extreme, following from the emblematic rebel governance cases are examples where the state has failed to provide governance and non-state actors, such as rebel groups, step into this void (e.g., Somalia and Somaliland). States, particularly in developing countries, provide security, goods and services to varying degrees (Cammett and MacLean Reference Cammett and MacLean2014; MacLean Reference MacLean2017). There are therefore examples of weak states where the state outsources components of governance, such as the provision of health care or clean water, to international NGOs (Mayer and Phillips Reference Mayer and Phillips2017). Further, alternative governing arrangements can include instances where one state provides governance over another state, as in the case of colonialism, informal empires, protectorates, or spheres of influence (Lake Reference Lake2011). In other cases, the state and religious authorities co-provide governance, as in the case of Islamic law in Iran. The most common condition of governance for most citizens is therefore likely one of multilayered governance where states, armed actors, private entities, NGOs, and other sources of authority compete and cooperate to provide security, goods and services.

Advances in the study of rebel governance elaborate the multilayered environments in which actors govern (Staniland Reference Staniland2012). In the introductory essay to a special feature in Civil Wars, Kasfir, Frerks, and Terpstra (Reference Kasfir, Frerks and Terpstra2017) detail the ways in which rebel groups, along with police, foreign interveners, and other actors, create a polycentric field of governance, complicating prior studies of governance during armed conflict. Stel’s (Reference Stel2017) work in this feature debunks the zero-sum logic of governance in the case of the PLO in Lebanon and instead demonstrates a continuum of mediated governance.

These innovations in the study of rebel governance call us to question the impact of multilayered governance on the individuals who live in these complex regimes. For example, under what conditions does the presence of multiple sources of governance improve social welfare outcomes? Engaging the literature on market economies, could it be the case that competition over the provision of security or goods and services increases the quality of these goods? It is also possible that living under multiple forms of governance poses certain cognitive challenges for individuals. Does the possibility of “forum shopping” for governance increase or weaken individuals’ sense of security? There are also broader questions for state building. For example, under what conditions is multilayered governance more or less stable than concentrating governance power solely with the state?

To answer these questions, the study of rebel governance needs new data collection efforts that are less state-centric in their conceptions and measures to better capture governance in multilayered environments. One approach, for example, might be to collect objective and attitudinal measures at the individual level that include qualitative life-history interviews to document what individuals have received from which provider and when. Other individual measures could include survey measures that capture welfare and attitudes toward various state and non-state governors. At other levels of analysis, studies should document governor and government quality and effort of governance as well as how the multiple layers of governance intersect. Often such measures are of the highest quality and most complete for states, but as research on rebel governance shows, that may reflect less the actual range of governance activities and more the existing data collection biases.

Argument 2: Giving Up Power Sometimes Gives You More Power

The literature on rebel governance centers on the benefits governance behaviors bring to the group, primarily in terms of increased local legitimacy, increased combat effectiveness, and improved information gathering. However, the variety of governance arrangements that exist in practice suggest that governance can constrain rebels as well as empower them. Critically, more governance does not directly translate to more power for rebel groups. Instead, some governance behaviors constrain rebels, putting limits on their war-fighting capacity in the short term.

The constraining effects of governance institutions is well studied for states (cf. literature on democratic and autocratic institutions, such as Geddes (Reference Geddes2003), Weeks (Reference Weeks2008), Putnam (Reference Putnam1988)). The development of this constraining relationship is seen as essential to modern state development in Europe and beyond (Bendix Reference Bendix1980; Slater Reference Slater2010). While work on rebel governance has acknowledged the back and forth negotiations occurring between civilians and rebels (cf. Arjona Reference Arjona2016), there is room to explore more directly when and how governance choices constrain rebels. Rebels can tie their own hands—much as states do—in a variety of ways, and some forms of this behavior are likely to be more or less durable.

We know that rebels can and do think strategically about allowing constraints on their behavior. For example, taking direct financial or military support from outsiders often comes with important conditions (Salehyan, Gladitsch, and Cunningham Reference Salehyan, Gleditsch and Cunningham2011)Footnote 1 and thus shape rebel governance decisions (Huang and Sullivan Reference Huang and Sullivan2020). Jo (Reference Jo2015) details how rebel groups make and keep legal agreements constraining their behavior. For example, some rebel groups allowed the International Committee of the Red Cross to visit detainees in compliance with the Geneva Conventions, signaling their willingness to abide by international law (Jo Reference Jo2015, 184). Fazal and Konaev (Reference Fazal and Konaev2019) show that half of rebel groups signed a commitment to ban landmines when approached by Geneva Call, an NGO that promotes rebel group adherence to international humanitarian norms. In each of these examples, rebels chose to give up some power today for possible longer-term benefits.

Local governance institutions can play a similar role in tying rebel’s hands. Mampilly and Stewart (Reference Mampilly and Stewart2021) suggest there are a number of ways rebels integrate civilians into governance structures, such as through local councils in rebel-held areas, that can ultimately constrain rebel behavior. Breslawski (Reference Breslawski2021) demonstrates that the inclusiveness of rebel institutions varies depending on the cohesion of the local community pre-conflict, and that rebels are willing to constrain their direct power when they see civilian goals as more aligned with their own. Cunningham, Huang, and Sawyer (Reference Cunningham, Huang and Sawyer2021) highlight the use of popular elections by rebels, an institution classically associated with increased accountability. Sawyer, Bond, and Cunningham (Reference Sawyer, Bond and Cunningham2020) show that rebels that choose to employ electoral governance institutions are less likely to commit acts of sexual violence against civilians, a practice that has been associated with both strategic choice on the part of rebels (Cohen Reference Cohen2016) and lack of control of rank and file (Butler, Gluch, and Mitchell Reference Butler, Gluch and Mitchell2007). Rebels also act locally to codify regulations and provide legal order, sometimes directly to their detriment, when they must address wrongs perpetrated by their own soldiers (Loyle Reference Loyle2020).

In addition to establishing participatory institutions and legal order, rebel groups use referenda projects strategically, leveraging non-sanctioned democratic behavior to pressure the state. This is particularly the case for autonomy- and independence-seeking rebels, such as the 2017 independence referendum in Nagorno-Karabakh or the referendum for independence by the Anjouan People’s Movement in Comoros in 1997 (Mendez and Germann Reference Mendez and Germann2018). These referenda can reveal the power behind such movements, but they can also constrain rebel actors when outcomes are not in perfect alignment with their preferences. Indeed, Balcells and Cunningham (Reference Balcells and Cunningham2020) suggest that competition for power within independence movements is a driving force behind many referenda as actors seek to lock in positions of public support among the local community.

Work on rebel governance demonstrates that rebel groups are willing to give up power to stay in power, raising a number of unanswered questions. Foremost among these is the question of whether these constitute actual constraints versus “window dressing.” Rebels may enact constraining behaviors without a true commitment to rule following, accountability, or civilian exercise of power. However, literature on international organizations suggests that the creation, maintenance, and continued adherence to constraining institutions and practices can change actors’ preferences and behavior over time (cf. Martin Reference Martin1994; Keohane and Martin Reference Keohane and Martin1995). Do these patterns apply to rebel groups? There are other important questions: When are governance constraints effective and what are their broader effects on vulnerable populations, such as women in conflict settings? How do the multiple potential audiences of their behavior respond to the use of constraining behavior? Is it useful to try to characterize rebel institutions the way we do states, focusing on democratic versus autocratic institutions and variations within them (Downing Reference Downing1993; Weeks Reference Weeks2008) or perhaps focused on veto points (Tsebelis Reference Tsebelis2002)?

To answer these questions, we need new data collection and more in-depth studies of particular governance behaviors. Perhaps as a first step this work should include better conceptualization and measurement of effectiveness and of support from different audiences. Individual-level survey work, similar to Revkin (Reference Revkin2021), is a promising avenue toward this end. In addition, interview and focus group data can gauge individual and small group dynamics. At the rebel group level, a more systematic measure of institutional variation and veto points will allow for better identification and comparability of institutions, as well as for theoretical advances in understanding how rebel institutions vary and relate to other constraints, including from the state.

Argument 3: The Right to Rule Requires the Right Rules

Research into the governance practices of rebel groups has primarily conceptualized governance as a path to legitimacy. Building on the early rebellion philosophies of Che Guevara and Mao Zedong, the literature ascribes governance institutions to those groups seeking to demonstrate capacity, arguing that establishing this capacity is important for winning over and ultimately pacifying the civilian population (see a discussion in Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011). While a useful heuristic for examining those groups with long term state-like governance aspirations (cf. center-seeking groups; Stewart Reference Stewart2018), this framework overlooks other potential governance aims such as warfighting, information gathering, and social control. In other words, rather than an attempt to build legitimacy, as Guevara and Mao envisioned, rebel governance is also employed as a tool of coercion. While rebel groups wield force and often have a monopoly on the use of that force in a given territory, it is less clear when and how these groups derive legitimacy from the civilian population and the impact that legitimacy has on warfighting ends. If we refrain from assuming a positive relationship between rebel governance and legitimacy, the question becomes why do rebels seek to build legitimacy and what is the role of governance institutions in achieving that aim?

Legitimacy is a concept that captures the “beliefs that bolster willing obedience” (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009). A legitimate rebel group has successfully harnessed these beliefs to be “the rightful wielder of power, maker and interpreter of rules or user of force and who thereby warrants support and compliance” (Podder Reference Podder2017, 687). Although it is possible to rule through coercion, legitimacy makes governing easier and more effective (Tyler Reference Tyler2006). As legitimacy is often seen as zero sum, the focus within much of the rebel governance literature has been on the ability of rebel groups to undermine the legitimacy of the state in order to strengthen their own (Podder Reference Podder2017). As Ledwidge writes, “It is the job of the insurgent to drain that [legitimacy] reservoir and refill it with his own capital” (Reference Ledwidge2017, 18). Again, this view starts from the premise that legitimacy is both useful and central to a rebel group’s warfighting aims.

New work on the topic of rebel legitimacy challenges this premise. To begin, not all rebel groups are legitimacy-seeking. Groups that do not rely heavily on civilian support (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2006) or those groups more focused on international backing (Coggins Reference Coggins2014) may forgo efforts to compel compliance from the civilian population and instead expend resources on “monitoring and enforcement” (Levi, Sacks, and Tyler Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009). It may be that there are costs associated with these legitimacy-building activities that the group is not willing to take on, or not willing to take on at a given point in time. Other groups, such as those with secessionist aims, may be interested in legitimacy but only among a certain population or in a particular spatial location. The decision of a rebel group to seek legitimacy is shaped by the need for civilian resources (Weinstein Reference Weinstein2006), the group’s mobilization efforts (Loyle Reference Loyle2021), as well as civilian demand for governance (Florea and Malejacq Reference Florea and Malejacq2018).

While states derive legitimacy from international claims to sovereignty, rebel groups do not enjoy the same universal legitimizing principals (Huddleston and Loyle N.d.). Legitimacy-seeking rebel groups adopt a variety of tactics to achieve this aim. Most central to the study of rebel governance have been those groups that adopt governance structures to enhance legitimacy, such as the provision of goods and services (Huang Reference Huang2016a) or the creation and enforcement of laws (Ledwidge Reference Ledwidge2017; Loyle Reference Loyle2021). Other legitimization strategies include mechanisms for hand tying (Jo Reference Jo2015), civilian consultation (Jaskoski Reference Jaskoski2020), the use of referenda (Balcells and Cunningham Reference Balcells and Cunningham2020), and the codification of transparent rules through rebel constitutions (Reed, Sawyer, and Ventura Reference Reed, Sawyer and Ventura2019).

Given the variation in desire and tools for seeking legitimacy there are still disparities in terms of when these strategies result in support from the population. What characteristics of legitimacy-seeking behavior are most likely to produce the desired outcomes? Characteristics of state legitimacy, such as government performance, administrative competence and procedural fairness are likely to also impact citizens’ views of rebel legitimacy. Rebel groups that deliver on their promises to provide social services and are deemed competent to deliver on future promises are more likely to be seen as legitimate (Flynn and Stewart Reference Flynn and Stewart2018). For example, groups with arguably higher levels of legitimacy among the civilian population often have a degree of transparency and inclusion in their governing processes. The firdi baito—local courts run by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in Ethiopia—operated with a strong degree of local autonomy (Loyle Reference Loyle2020). The National Resistance Movement in Uganda incorporated a high level of civilian participation and democratic elections in the village committee system (Kasfir Reference Kasfir2005). It may also be that civilians consider rebel leadership and governance structures co-opted from existing authority systems, such as tribal authorities or Sharia courts, to be more legitimate (Mukhopadhyay Reference Mukhopadhyay2014).

Civilians have a role to play in this process both as the actors who grant legitimacy as well as a force that shapes the conditions under which that legitimacy will be conveyed (Dorff Reference Dorff2019). New work by Florea and Malejacq (Reference Florea and Malejacq2018) traces the demand side of rebel governance whereby under certain conditions civilians lobby for the creation of rebel institutions and service provisions. On occasion rebels are reluctant rulers responding to strong demand from the civilian population for the provision of governance despite other military priorities. For example, the CPN-Maoist in Nepal created their court structure as a direct response to the deficiencies of the state in creating law and order (Sivakumaran Reference Sivakumaran2009). The PIRA in Northern Ireland are often credited with policing local crimes in response to pressure from the Nationalist community (Munck Reference Munck1984). Rebel governance created at the behest of the civilian population is likely to be seen as more legitimate than are more top-down rebel projects.

Despite the advances on the question of legitimacy in the field of rebel governance, there is still more we need to know. We have yet to develop a clear understanding of when and why rebels seek legitimacy. Central to this is the question of when is legitimacy needed to fulfill warfighting aims? Cases such as the NRM in Uganda suggests that legitimacy-seeking is not solely the purview of secessionist groups nor is it solely born of revolutionary ideologies. International audiences likely have a role to play both in conferring legitimacy and shaping domestic claims to legitimacy (Coggins Reference Coggins2014, Jo Reference Jo2015). Furthermore, new research is needed to explore the demands and agency of civilians in their complicated interactions with rebel governors around them. Levi, Sacks, and Tyler (Reference Levi, Sacks and Tyler2009) identify the concept of behavioral legitimacy that differentiates actual compliance from coercion or other forms of acceptance of an actor’s rule. When do civilians willingly obey rebel leaders? The process of rebel rule is iterative and responsive so we should also expect behaviors and relationships to change over time (Mampilly and Stewart Reference Mampilly and Stewart2021).

Answering questions of legitimacy calls for the use of new research methodologies such as the use of survey data and survey experiments to learn more about the people living under rebel rule, the degree of civilian agency, and citizens’ governance preferences. New techniques in natural language processing could shed light on the kinds of arguments used by members and organizations alike to make their appeals to legitimacy. Like work by Loyle and Bestvater (Reference Loyle and Bestvater2019) cataloging the use of social media by rebel group leaders, advances in this area could lead to a greater understanding of the ways rebel groups appeal to the civilian population.

Argument 4: You Don’t Need Roads to Rule

Existing studies largely view rebel control of territory as a necessary condition for rebel governance. Whether implicitly or explicitly, studies hold that physical control of land enables rebel groups to engage in the building of administrative and bureaucratic institutions, infrastructure, and social services. These governance engagements, in turn, allow rebel groups to exert authority over people who populate the territory. Hence territory enables control, and institutions and infrastructure enable governance. Conversely, a lack of territorial control or a situation of contested territorial control should drive rebel groups to fight intensely to (re)gain territory so that they can (re)create order through governance. Control of physical space is thus seen as a prerequisite for rebels’ exercise of local authority, and territorial expansion a sine qua non for rebels’ success (Kasfir Reference Kasfir2005; Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2006; Anders Reference Anders2020).

This view of territorial control mirrors the wider scholarship on state formation and statebuilding, which sees territory as central to the formation and strengthening of the state. The Weberian definition of the state specifically refers to a defined territory on which a government sits (Weber Reference Weber, Gerth and Mills1946), and building a state requires a ruler to become a “stationary bandit” who sets down roots in a given territory for more efficient resource extraction (Olson Reference Olson1993). Likewise, European state formation was a byproduct of wars of conquest and territorial expansion (Tilly Reference Tilly1990), while a major challenge of African statebuilding was that states had difficulty extending their reach into peripheral regions (Herbst Reference Herbst2000, 2). State infrastructural power, according to Mann, is the “institutional capacity of a central state … to penetrate its territories and logistically implement decisions” (Reference Mann1984, 113, emphasis added). State power, in other words, cannot be understood apart from a study of how the state reaches into, controls, and governs its territories.

As applied to rebel groups, however, an uncritical assumption of local control and governance as tied to land can be more constraining than revealing (cf. Rubin and Stewart N.d.). While territorial control remains a fundamental aspect of violent rebellion, rebels understand that survival often hinges critically on their ability to gain support from local civilians and external states. And while territorial control can certainly facilitate rebel governance, features of contemporary civil conflicts suggest there is much beyond territorial control that enables rebel groups to govern, foster social relations with civilians, and appeal for external support. These notions further suggest that today’s violent conflicts take place in contexts that have changed dramatically in the contemporary era, and that our understanding of how armed rebels project authority and govern should be revised accordingly.

Here, we focus on four modes of rebel governance of civilians that are distinct from, and unencumbered by, rebels’ degree of territorial control. First, today’s rebel groups govern as much by occupying digital space as they do geographical space. Rebel groups are increasingly active on social media such as Twitter (Loyle and Bestvater Reference Loyle and Bestvater2019), broadcasting streams of messages that create and maintain a wide following in an online “imagined community” of sorts (Anderson Reference Anderson1983). While the effects of rebels’ social media use have yet to be systematically analyzed, it is clear that rebel groups use social media for standard governance purposes including propaganda, self-promotion, and public outreach, with messages aimed as much at international as local and domestic audiences (Blaker Reference Blaker2015; Jones and Mattiacci Reference Jones and Mattiacci2019; Loyle and Bestvater Reference Loyle and Bestvater2019). But rebel groups’ use of the Internet goes beyond propaganda and communication; rebels have recourse to highly robust “virtual sanctuaries” that facilitate online financial transfers, recruitment, and clandestine planning and communication (Kilcullen Reference Kilcullen2006, 113). These new Internet-based modalities of rebel operations are not only often exceedingly difficult for the state to track and dismantle, they can also obviate the need for more traditional forms of governance infrastructure such as rebel-operated banks and TV stations—infrastructure that often require rebel control of territory and can be directly targeted by state forces.

Second, rebel groups often deliver social services via “on the spot” governance that requires neither firm territorial control nor significant investments in infrastructure. In Nepal, for example, the Maoist rebels dispatched mobile courts that traveled to villages to hear cases (International Commission of Jurists 2008, 8). In Benghazi and other Libyan towns, armed and unarmed opposition actors set up local committees to oversee food distribution, humanitarian aid, and other services in mere days following the start of mass protests against the Qaddafi regime in 2011. Within two weeks, the opposition had coalesced into the National Transitional Council (NTC). This rapid bottom-up organizing was enabled less by rebel territorial control—which was nascent and at best tenuous—but by the swift dissolution of local state authority along with the widespread defection of senior state officials to the opposition (Lacher Reference Lacher2020, 19–21). In other cases, rebel groups can co-opt state services or negotiate their way into the state governance structure, thus creating a hybrid governance system that reaches a wide swathe of the population. The Taliban has governed in this manner in recent years, leading one study to conclude that “the Taliban do not have to take territory to control it” (Jackson Reference Jackson2018, 25).

Third, rebel governance can be a-territorial at its top echelons when its administrative center or executive leadership is a political, rather than an infrastructural, creation. Governance is about more than providing services to local communities; it also involves establishing oneself as an authority and legitimating that claim to authority. When the NTC declared itself “the sole representative all over Libya” in early March of 2011, it was a hastily assembled governance body that could only claim weak control of some eastern towns (Lacher Reference Lacher2020, 21).Footnote 2 Regardless, France responded within days to recognize the NTC as the sole legitimate representative of the Libyan people; other foreign governments soon followed.Footnote 3 In addition to creating a political body, a rebel leadership can also boost its credentials by introducing conventional trappings of statehood such as flags, slogans, and insignia that collectively signal their claim to political authority over people (Mampilly Reference Mampilly2011). Research finds that such performative acts do have effects on governance. The Tamil Tigers’ use of symbols of legitimation during its war against Sri Lanka, for example, “not only consolidated its grip on the Northeast, but also engineered a level of support and compliance” from the local populace (Terpstra and Frerks Reference Terpstra and Frerks2018, 1001–1002).

Finally, rebel groups can govern from abroad, irrespective of their level of local territorial control. The top leader of the Free Aceh Movement (GAM), Hasan di Tiro, ran a self-styled government in exile in Sweden for almost the entire duration of the group’s secessionist war against Indonesia (Aspinall Reference Aspinall2009, 104–105). While GAM made governance efforts both locally and abroad, other rebel groups are more focused on external outreach (Tull Reference Tull2005, 123). Many rebel groups maintain “diplomatic” wings in foreign capitals to oversee their external outreach efforts (Huang Reference Huang2016b). If public outreach is an aspect of governance, these activities abroad, like rebel activism on social media, further reinforce the idea that rebel groups operate well beyond the confines of what local territory they may hold at any given time.

The question, then, is not whether territorial control is necessary for rebel governance, but what are the relative benefits and costs of governance within a physical space versus in cyberspace or through a political-administrative leadership that is not tied to territory? Such a research agenda would be consistent with the understanding that the locus of control has become increasingly detached from geographical space in recent decades for state and nonstate actors alike. What, then, does building roads do for rebels, in comparison to building a social media presence or a foreign presence? In what other ways do rebels capitalize on new technologies or foreign sanctuaries for governance purposes, and to what effects?

These questions broaden our understanding of rebel governance as a function not merely of physical control, but also of social, ideational, and technological control. Given the relative novelty of rebel use of cyberspace, there is ample room in future research for deep case study work, as well as innovative use of big data on rebels’ internet and social media use, on the effects of technological control. Studies can also use social network analysis to map out rebel groups’ nodes of contacts and bases abroad and examine how these networks enable war-fighting, governance, and legitimation. Paired with geo-spatial measures of the extent of territorial control, alternative measures of control will elucidate new theoretical insights.

Argument 5: Where You Stood Determines Where You Now Sit

Conflict institutions affect many long-term governance outcomes in post-conflict states, including the post-conflict rule of law (Loyle Reference Loyle2020), regime type (Huang Reference Huang2016a), social cohesion (Kubota Reference Kubota2018), and health care systems (Ghobarah, Huth, and Russett Reference Ghobarah, Huth and Russett2003). However, many open questions remain about the lasting impacts of rebel governance on societies, civilians, and state governance following conflict.

The rebel governance literature has been primarily focused on the drivers of rebel governance rather than its outcomes. Notable exceptions suggest that rebel governance can have long-term impacts on state institutions. Huang (Reference Huang2016a), for example, demonstrates that postwar regimes are deeply rooted in wartime rebel governance experience (cf. Slater Reference Slater2020). Rickard and Bakke (N.d.) show that paramilitary reliance on informal systems of “punishment attacks” and vigilantism in Northern Ireland has had lingering effects on support for the judiciary and policing in Northern Ireland, even two decades after the Good Friday Agreement.

Rebel governance also shapes post-conflict representation. Many rebel institutions provide leaders and citizens with institutional experience and expertise that may help post-conflict societies recover more quickly. Loyle (Reference Loyle2020) demonstrates the presence of learning mechanisms which transfer skills and expectations from rebel judiciaries to post-conflict rule of law. Rebel elections and rebel participation in elections during conflict may make their transition to participating in the post-conflict political system smoother, and the establishment of coherent, organized political parties easier (Cunningham et al. 2021). Candidates who participated in rebel governance have a record to run on, leading to governance experience and potentially higher quality candidates. Early work into these questions highlights many interesting facets: Dresden (Reference Dresden2017) argues that certain rebel capacities will translate more easily into post-conflict political competition, while Zaks (Reference Zaks2021) examines under what conditions rebel structures better enable rebel group-to-political party transitions. On the other hand, Stam and Horowitz (Reference Stam and Horowitz2014) show that of all heads of state, those who are former rebels are the most likely to use force, potentially implying that politicians with former experience in rebel governance may behave differently than non-former rebels.

The long-term effects of rebel governance—both for conflict dynamics and for individuals who have lived under rebel rule, or under dual-governance—are still poorly understood and leave many unanswered questions. For example, it is unclear how the process of post-conflict state-building will be affected by the experience of rebel governance. There is evidence that criminal governance complicates state-building (Bateson Reference Bateson2020; Jung and Cohen Reference Jung and Cohen2020; Moncada Reference Moncada2017), but the political nature of rebel governance may facilitate state-building if rebel governance institutions could be co-opted. While there is mounting evidence that civilians prefer harsh governance (by the state or the rebels) to ambiguous control (Revkin Reference Revkin2021), the long-term success of re-establishing robust institutions remains unclear.

Rebel governance offers scholars of governance an unusual view into civilian life under multiple regimes and institutions—often simultaneously—but we do not know yet what the psychological implications of these experiences are, for individuals or for society. Berry (Reference Berry2018) and Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytiov, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016) document the potentially transformational role of conflict on society—in generating social and political participation, particularly from previously marginalized members of society such as women. How does rebel governance strengthen or attenuate post-conflict post-traumatic growth or expectations around social engagement? How does it shape civilian assessments of the quality of governance, and expectations of the governed? Revkin shows that in Mosul these elements were critical to civilians’ migration decisions (Reference Revkin2021), but we know little about the long-term effects following conflict, and about how civilians adopt and re-adopt different views of citizenship and identity during periods where they experience different or layered governance.

To answer these questions the study of rebel governance must expand its data collection and theorizing, both at macro and micro levels. Archival and qualitative work on the historical roots of institutions can shed light on the institutional legacies of rebel governance. The effects of rebel governance will form a critical new piece of the state-building literature, which has often focused on the role of external states in the building process. Similarly, the role of rebel governance in transforming civilian life, particularly around core human rights like education, literacy, and health care is not fully understood (Jo Reference Jo2015). At a micro-level, questions on the legacies of rebel governance for individuals should look more closely to innovations in surveys and experiments to understand within-person assessments and the psychological effects of rebel governance.

Conclusion

The phenomenon of rebel governance has generated a burst of scholarship in conflict studies in recent years. And yet there remains significant room for further study of how, when, and why armed non-state actors seek to govern civilian communities. In this article, we reflect on a generation of scholarship on rebel governance and identify five areas of inquiry, summarized in table 1, which, if pursued, would help advance our understanding of rebel governance to a new level in the coming generation of scholarship.

Table 1 Summary of arguments

These areas reflect the state of the rebel governance literature in parallel with the broader study of civil war and governance in the state-building tradition—two critical literatures from which rebel governance scholarship has grown. As scholarship on civil war emerged as distinct from work on social revolution,Footnote 4 key assumptions from the study of international conflict took root, including the zero-sum nature of conflict and assumptions about rebel actors as solely aggressive power-seekers vying for territory and control. Earlier work on rebels as governors leans heavily on how such actors mimic and aspire to statehood, which led to an overfocus on territorial control and the ways in which state-like actors maintain legitimacy. The final argument brings rebel governance forward in time to the post-conflict environment, connecting this work to governance studies inside and outside the state-building tradition. Collectively, the five arguments urge a reconsideration of some of the most fundamental aspects of rebel governance, including its relationship to state governance, its institutional design, the role of legitimacy, its relation to physical territory, and its post-conflict legacies.

In addition to these five arguments, another way to bring the research agenda forward is to focus on causal mechanisms. For example, what explains why some rebel groups are more legitimacy-seeking than others, why some rebel groups embrace hand-tying institutions and others do not, and why some rebels prioritize local territorial control while others opt for extraversion? While existing work has identified organizational features and rebels’ concern for international support, new work would likely also be enriched by established theories, including theories of collective action (e.g., use of selective incentives to gain civilian compliance), bargaining (between rebels and civilians), deterrence (of rebel defection), signaling (of future intent), cheap talk (via social media), and historical legacies (for understanding post-conflict trajectories). In other words, theories developed elsewhere in political science offer much utility for understanding rebel behavior. In turn, exploiting these theories helps to better incorporate rebel scholarship into the rest of political science, in lieu of building a “rebel research” silo.

Advancing our understanding of rebel governance has broader implications for how we tackle some of the most pressing social issues of the day, including the need for crucial services such as public health and education, as identified earlier. The United Nations, for example, continues to identify education as a critical component of development, including education indices as a key part of the Millennium Development Goals. Between 2005 and 2015, over $120 billion (US) was spent to promote education globally.Footnote 5 The United States alone has devoted $11.2 billion in 2020 to increasing global health outcomes, the vast majority provided bilaterally (state to state).Footnote 6 These initiatives are predicated on the idea that—particularly in times of conflict—the state is the only, or at least the primary, provider of governance on the ground. In challenging that idea, the research agenda put forward here opens space for an exploration of how rebel governance intersects with these global initiatives, as well as the implications of different rebel governance experiences on the ability of a variety of actors to meet these challenges.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge support from the Ostrom Workshop at Indiana University for hosting their program on Rebel Governance in May 2019, along with workshop attendees Jessica Braithwaite, R. Joseph Huddleston, Michael Rubin, and Megan Stewart.