6.1 Introduction

Polycentric thinking seeks to develop a more holistic picture of governance (see Chapter 1). Polycentric governance theory acknowledges that, in addition to nation states, other initiatives contribute to the shaping of collective orders. They involve local governments, businesses, civil society organisations and social movements. A core proposition identified in Chapter 1 is that an experimental search for governance arrangements within diverse local settings will lead to effective solutions, performing better than states or some kind of monocentric, globally oriented system of governance. This reflects awareness of complexity and limits of central control, which require ‘reflexive governance’ (Voß and Kemp, Reference Voß, Kemp, Voß, Bauknecht and Kemp2006).

An interesting paradox, however, is that while polycentric thinking acknowledges the complexity of ecological and social systems, it says little about the complexity of social processes that are involved in devising, carrying out and evaluating experiments. This leads to a highly reductionist conception of governing. Of course, experiments help involved actors to learn about what is actually being tested and they contribute to problem resolution in that way. But how are decisions taken on what to test and how? What role do politics and power play here and how do they affect the experiments? Do actors experience different effects from the outcomes of experiments with new forms of collective order, or already from the process of undertaking them? To what extent are their various concerns and aspirations addressed by experimental processes, and how are they negotiated with each other? If we consider that all experimentation is deeply embedded in institutional, cultural and material settings and asymmetric power relations, we quickly realise that just by leaving institutional development up to decentralised trials, we may not promote universally best solutions, but in fact help already powerful actors to assert their visions of collective order against others (cf. Voß and Bornemann, Reference Voß and Bornemann2011).

Our first aim in this chapter is to increase awareness of the fragility of expectations that are linked with this conceptual weakness in polycentric governance thought. We point to the idealistic assumptions about experimentation that the current discourse of polycentric governance hinges on. Following from this, our second goal is to offer a systematic account of where and how politics play out in the course of doing experiments, and to draw attention to the fact that in real-world contexts, experiments are likely to be shaped by asymmetric power relations. Our third goal is to caution against the uptake of polycentric and experimental governance concepts for orientating or legitimating governance interventions, unless a more realistic understanding of the practices of experimentation is taken as a starting point.

Before we start, let us introduce two key terms that we refine as we move along. Experimentation refers to the deliberate production of experiences for finding out what works.1 Politics is understood as the making of collectively binding decisions selecting from a diversity of deliberately judgments some to be realised.2 Broadly defined, the politics of experimentation thus occur whenever, throughout a process of creating novelty and making experiences, diversity is transformed into unity. Most obviously, this happens when controversies over findings are fought out in public, but it also occurs more inconspicuously when decisions are made about what needs to be known, which hypotheses are to be tested and which observations are to be made. Often, no one cares to contest such decisions as they are thought to be just epistemically, but not politically relevant.

6.2 Experimentation in Polycentric Governance

A closer look at the polycentric governance literature reveals that, even if it has developed into a much broader evolutionary philosophy of governance, it still carries forward some of the ontological assumptions from institutional economics (Ostrom, Gardner and Walker, Reference Ostrom, Gardner and Walker1994; Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2011; Cole and McGinnis, Reference Cole and McGinnis2014; Thiel, Reference Thiel2016). Polycentric governance theory emphasises decentralisation, local embedding and responsiveness to specific contextual conditions, along with the potential to mobilise entrepreneurial initiatives, also against incumbent powers and rigid institutions. The underlying imaginary is a constantly evolving institutional landscape (see Chapter 1). As such, the concept immediately attracts attention as a preferable alternative to the cumbersome business of coordinating state action on global problems like climate change through international diplomacy (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010; Cole, Reference Cole2015; Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017). The concept offers hope in times when ‘big politics’ appears to fail. Yet the expectation is not only that self-organisation will step in to fill gaps that are left open by state government and international institutions. The current discourse also raises the expectation that it would be actually preferable to actively withdraw state oversight to leave more space for self-organised institution building, because this would produce forms of governance that are better adapted to a diversity of socio-ecological contexts, and would thus be more effective and legitimate.

All this hinges on particular assumptions about experimentation that are imported from the functionalist evolutionary theory of institutional economics that originally inspired the articulation of the concept. First, there is the assumption that new institutions are freely created (in effect, randomly generated variations). And second, that selection works on the basis of feedback and adjustment within particular contexts (leading to a survival only of the fittest, best-adapted institutions that generate maximum utility for those who adopt them). Only if these assumptions about the inner workings of experiments are correct can we assume that experiments deliver trial-and-error learning that eventually results in governance that works well for all. When these assumptions are incorrect, however, the result would be quite a different scenario. Curtailing the regulatory monopoly of the state and liberalising the market for experimental institution building may, in this scenario, fail to bring about a world of governance bubbling with creativity and responsively adapting to the needs of the people, and instead lead to the emergence of a private oligarchy that can work more or less undisturbed by constitutional rules, public accountability and democratic control – which would have applied under a more monocentric or state-led system of governing.

Let us take a closer look at experimentation in polycentric governance. It generally appears as a central proposition in the discourse (Ostrom, Reference Ostrom2010; Cole, Reference Cole2015: 115; Dorsch and Flachsland, Reference Dorsch and Flachsland2017; see also Chapter 1). There is overlap with partly connected discourses of experimentalist governance (Sabel and Zeitlin, Reference Sabel, Zeitlin and Levi-Faur2012; De Búrca, Keohane and Sabel, Reference De Búrca, Keohane and Sabel2014) and experimentation for sustainability and decarbonisation (Kemp, Rip and Schot, Reference Kemp, Rip, Schot, Garud and Karnøe2001; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011; Sengers, Wieczorek and Raven, Reference Sengers, Wieczorek and Raven2016), or more specific discourses on urban experiments (Bulkeley and Castán Broto, Reference Bulkeley and Castán Broto2013; Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller, Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014; see more generally Ansell and Bartenberger, Reference Ansell and Bartenberger2016). Despite its centrality, however, the concept of experimentation is weakly developed in polycentric governance theory. Experiments are primarily understood as idealised methods, or are understood through the lens of expected effects (producing a variety of new and robust innovations), but not so much through the lens of the social processes in which they are done and from which actual effects could emerge.

We can discern two strands of philosophical thought in the literature on experiments in governance: a positivist-utilitarian strand and a pragmatist-interpretivist strand. In both strands, experiments are understood to generate solutions to perceived problems by trying out what happens when visions are put into practice. A fundamental difference is, however, that the former sees experiments as a process of adapting to reality, and the latter sees them as a process of making reality. Let us elaborate. The positivist-utilitarian framework assumes that the subjective and the objective world are ontologically separate. The generation of theoretical hypotheses is a matter of human ingenuity while the senses, if methodically controlled, can provide neutral data of an independently existing, objective world. The key task of experiments, then, is to provide empirical observations for selecting theoretical hypotheses about institutional designs and their effects (Campbell, Reference Campbell1969; Stoker and John, Reference Stoker and John2009; Abbott and Snidal, Reference Abbott and Snidal2016). Within the pragmatist-interpretivist framework, however, the world is understood to be essentially in flux. Subject and object are both part of this process. Within it, human imagination and the material world constitute each other, mediated by motoric and perceptual capabilities, in active human interventions and the experiencing of consequences. Experimenting thus is a way of deliberately changing the world. It enables learning, not about a pre-existing reality, but about the possibilities of knowing and doing reality differently. It is never neutral, but always geared towards specific concerns, and irreversibly transforming the world (Dewey, Reference Dewey and Boydston1986; Evans, Reference Evans2000; Ansell, Reference Ansell, Bevir and Rhodes2016).

While epistemologically these two strands of experimental philosophy are fundamentally different, neither of them provides fine-grained discussions, or illuminating empirical analyses, of experimental processes in governance. In both strands, there is little concern for social interactions and the nitty-gritty of actually doing experiments. As a result, they both neglect the politics of experimentation. Positivists see experimentation as a way to bypass the political resolution of conflicts because ‘nature’ becomes instituted as a neutral arbiter. Decisions are handed over to the ‘jury of experience’, which becomes objectified through methods of science (Norton, Reference Norton2005: 79). Pragmatists, in contrast, do not assume neutrality, but unanimity or at least equality in the process of collectively conducting experiments (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2012). They assume that social interactions unfold under conditions of freedom and symmetrical relations – as explicated, for example, through Habermas’ (Reference Habermas1981) model of communicative action or Lindblom’s (Reference Lindblom1965) model of mutual adjustment. If politics is mentioned, it is restricted to something that exists outside of experiments: to how experimenters struggle with incumbent interests and ideologies or how different experiments compete for space (Misiko, Reference Misiko2009; Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2011; Bulkeley et al., Reference Bulkeley, Edwards and Fuller2014; Evans, Karvonen and Raven, Reference Evans, Karvonen and Raven2016).

The possibility that experimentation may be captured by dominant interests and used for them to realise their own particular visions of collective order is ignored in current discourses of polycentric and experimental governance, either because it is assumed that objective conditions will determine the course of experiments or that power is absent or symmetrically distributed among those involved in and affected by experiments. That is the case despite empirical case studies suggesting that experimentation in governance is imbued with conflicting interests and asymmetric power relations.

A prominent example is the case of ‘transition management’, which is heralded as an approach for experimentally searching for pathways of sustainable system transformations in energy, agriculture, mobility and so on (Kemp and Rotmans, Reference Kemp and Rotmans2009; Voß, Reference Voß2014). Experience with transition management in the Netherlands has shown that the process of defining experimental agendas and evaluating results can be easily captured by incumbent networks of administration officials and big companies for pursuing innovation strategies especially geared towards the growth and competitiveness of particular branches and firms (Kern and Smith, Reference Kern and Smith2008; Heiskanen et al., Reference Heiskanen, Kivisaari, Lovio and Mickwitz2009; Kern and Howlett, Reference Kern and Howlett2009; Meadowcroft, Reference Meadowcroft2009). This demonstrates the relevance of considering politics and asymmetric power relations, if experiments are not to undermine democracy and allow powerful actors to assert their interests (Hendriks, Reference Hendriks2008, Reference Hendriks2009; Voß, Smith and Grin, Reference Voß, Smith and Grin2009; Voß and Bornemann, Reference Voß and Bornemann2011; Pel, Reference Pel2016). Because we seek to address this deficit in the conception of polycentric governance, we now move to discuss where the politics of experimentation can be found more specifically.

6.3 The Politics of Experimentation: Configuring Experimental Infrastructure

The practice of experimental inquiry has been a focus in science and technology studies. This led to the insight that experimentation is a social process, with decision-making deeply embedded in historically grown cultural and institutional patterns with asymmetric relations and established power positions. A key finding of so-called laboratory studies is that experimentation not only takes place within a societal context that affects what comes to be known, but also within specifically configured material settings that are deliberately shaped according to particular research interests and theoretical constructions of the phenomena that are tested (Knorr-Cetina, Reference Knorr-Cetina, Jasanoff, Markle, Petersen and Pinch1995). Massive laboratory complexes are a case in point, but this also applies in less visible configurations as when sight is focused through a telescope or field studies are conducted by systematic surveying and the drawing of probes (Latour, Reference Latour1999). The general point is that, in practice, experimentation occurs in socio-material settings that are preconfigured according to some theoretical model of what it is that is to be tested, and that they, to a greater or lesser degree, provide for seclusion from the wider world (Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe, Reference Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe2009). This is one of the key conditions of success for modern science: by reducing, simplifying and purifying a complex macrocosm of ‘reality out there’, already before any experiences are made, it makes specific phenomena experimentally demonstrable and knowable that would otherwise always be overwhelmed by the complexity of actual interactions and continuous change. In effect, experimentation fabricates the realities that it comes to know, rather than discovering them in nature (Knorr-Cetina, Reference Knorr-Cetina1981; Hacking, Reference Hacking and Pickering1992; Rheinberger, Reference Rheinberger2005). This includes the careful composition of a collective of trained and professionally disciplined experimenters to cultivate convergent ways of thinking, intervening and sensing (Fleck, Reference Fleck1994).

Experimentation thus appears as a particular mode of collective ordering, working through three steps (see Figure 6.1): (1) the selective reduction of reality ‘in the wild’ by building simplified local realities; (2) the experimental construction of local realities for the creation and controlled reproduction of theorisable phenomena in a confined setting; and (3) the expansion of experimentally created orders, by claiming that theories and data describing these phenomena represent universal properties of nature and by developing technology to replicate them elsewhere.

Figure 6.1 Experimentation as ‘secluded research’. (Reference Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe2009)

In these three steps, the world becomes creatively transformed. At least with the final step of expanding experimentally configured orders, they also come to be binding on others who were not involved in making them. Against this background, scientific experimentation is claimed to work as ‘politics by other means’ (Latour, Reference Latour, Knorr-Cetina and Mulkay1983) or as a form of ‘ontological politics’ (Mol, Reference Mol1998).

An illustrative example from the world of climate governance is the way in which the Kyoto Protocol’s Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) was given shape through experiments that were set up for testing how emission reduction commitments under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) could be fulfilled through international cooperation. A reconstruction of the process shows how experimentation in pilot projects not only produced special expertise, exemplary working arrangements, and more generally applicable methods but also contributed to realise a particular version of international cooperation. This version was very much geared towards the interests of private investors, as it allowed the trading of carbon emission offsets (Schroth, Reference Schroth2016). When the concept of ‘joint implementation’ of national reduction commitments was introduced in the late 1980s by the Netherlands and further developed by Norway and the United States, it was highly controversial (Paterson, 1996; Trexler and Kosloff, Reference Trexler and Kosloff1998). Concerns over international justice, asymmetrical power relations between the North and South (see Chapter 18), capacity-building and technology transfer, efficiency and reduced costs for fossil-fuel intensive industries, as well as the mobilisation of private capital and the making of new markets, suggested different directions for developing the proposal and different criteria for evaluating what works. From early on, however, advocates like Norway, the Netherlands and the World Bank started with experiments to test and demonstrate how international cooperation could work. In the late 1980s, they started with small-scale experiments to generate emission offsets by electric companies investing in reforestation projects in Guatemala. In the early 1990s, projects with energy efficiency investments in Mexico were undertaken. From 1993, experimentation with joint implementation proliferated through a dedicated programme set up by the US government (Jepma, Reference Jepma1995). In 1995, the UNFCCC officially endorsed a pilot phase, then called ‘Activities Implemented Jointly’. The insights and technical designs that were brought forward in these experiments turned out to reflect concerns about the mobilisation of private capital and establishing a new market more than any other of the concerns originally raised and politically debated under the UNFCCC. With the social momentum, evidence and the technical solutions that were generated, a decade of experimenting had created a new reality. With the 2001 Marrakech Accords, experimentally constructed arrangements for a CDM were finally adopted as a flexible mechanism for implementing international commitments under the Kyoto Protocol.

Next, we take a closer look at what is at stake in each of the three dimensions of reduction, construction and expansion and where asymmetric power relations can shape the experimental process.

6.3.1 Reduction: Modelling the World and Building a Test-Stand

A first point at which decisions are taken is that a research problem is identified and a basic analytical framework is deployed, which is then translated into the design and installation of a ‘test-stand’. This is a specifically prepared observational setting, ‘a simpler, more manipulable reality’ that replaces the unselected and overwhelmingly complex world as it actually unfolds ‘in the wild’ (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe2009: 50). Many foundational decisions are thus taken before the actual experimenting starts. During the subsequent process, however, these arrangements move into the background, working as a hidden experimental infrastructure that is taken for granted as ‘trials on nature’ proceed. The presumptions and considerations that led into decisions on this initial set-up, or reflections on what was excluded from the outset and could therefore not be observed, tend to be forgotten when results are publicly presented (Latour, Reference Latour1987).

An example from the CDM case is that particular forms of economics and engineering expertise had been assembled with a focus on testing methods to verify emission reductions per invested dollar, by measuring emissions of several greenhouse gases, calculating baseline scenarios and allocating portions of declared reductions between host and investor. Specific projects and sites were selected against the background of this framing and agreements with involved actors were negotiated in this orientation (Schroth, Reference Schroth2016: 82–107). While these methodological decisions were presented as technical issues, they presupposed a decision for cost-efficiency and the mobilisation of private capital as primary purposes of joint implementation – an issue that in the wider public and in the UNFCCC was still controversially discussed.

6.3.2 Construction: Creating Ordered Phenomena in Seclusion

The actual carrying out of trials starts within a reality that has already been selectively reduced. It then takes place through an iterative process of refining theoretical propositions, designing interventions, making observations and fine-tuning the material setup for the next round of experiments. This involves decisions to specify the experimental agenda in dealing with situational contingencies and to arbitrate between various possible ways to make sense of what happened. Even if attempts are made to objectify criteria, it involves ‘interpretive flexibility’, which is to be overcome by social means like status, threat, rhetoric or negotiation (Gilbert and Mulkay, Reference Gilbert and Mulkay1982; Collins, Reference Collins, Knorr-Cetina and Mulkay1983). Making decisions within the research collective thus is a form of micropolitics that helps to arrive at shared results and create a new way of collectively knowing and doing reality among selected actors and within a confined local setting (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe2009: 52).

In the case of the CDM, crucial design issues and conclusions on the outcomes of experiments were resolved among experts involved in the pilot projects, coming from non-governmental organisations, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the World Bank, research institutes, companies and agencies (Schroth, Reference Schroth2016: 108–129). They translated the issue of shared global responsibility for climate change into an issue of measuring emission effects of investments, thus bypassing political processing of diverse concerns and instead pursuing a particular concern as an epistemic and technical matter of testing facts. Working out ways to make joint implementation work was thus removed from the political forum of the UNFCCC and shielded from broader public scrutiny. The selected group of experts eventually came to the conclusion that ‘in the absence of credits, investments in [joint implementation] projects will not reach the level necessary to fully realise the potential of this concept’ (Dixon, Reference Dixon1998: 3) – a technical answer to many politically fraught questions related to crediting, the involvement of private investors and even the overall purpose of international cooperation projects in the first place.

6.3.3 Expansion: Generalising Local Achievements

Finally, politics occurs in the generalisation of experimental findings. Initially, findings are only locally true. The challenge is to turn what a few people have learned within a particularly configured experimental space into a collectively shared fact. This requires a disconnection from specific interpreters and circumstances. Descriptions must be formulated in abstract, decontextualised ways. In order to reproduce findings and use interventions that have been tested in the confines of the experimental setting, the experimental infrastructure needs to be turned into a ‘technology’, a transportable package with a reliable function. In effect, it also requires that other sites within the macrocosm are reconfigured after the model of the experimentally arranged microcosm: ‘For the world to behave as in the research laboratory, … we simply have to transform the world so that at every strategic point a “replica” of the laboratory, the site where we can control the phenomena studied, is placed’ (Callon et al., Reference Callon, Lascoumes and Barthe2009: 65). To achieve this, the experimental collective needs to recruit broader support, mobilise collective action and build legitimacy in interaction with powerful stakeholders and broader publics.

In the example of the CDM, this challenge is clearly visible in bringing results from experiments back into the UNFCCC (Schroth, Reference Schroth2016: 130–148). Crucial for this was the generation of support by raising economic interests in replicating experimentally configured solutions. The World Bank played a key role here. It adopted procedures and methods, as had been developed in pilot projects under the US joint implementation programme, and adopted them in the guidelines for a new fund for private investors, the Prototype Carbon Fund. A larger constituency of firms and governments was thus enrolled for installing a new wave of projects after the concept of joint implementation as developed in the pilot projects, and thus for replicating that experimentally configured reality elsewhere. This generated momentum, which eventually led to a shift in international negotiations under the UNFCCC as resistance against a private offset market from the alliance of G77 and China crumbled (van der Gaast, Reference Van der Gaast2015). Finally, after the pilot phase of Activities Implemented Jointly, it was stated as a matter of fact that it ‘has demonstrated that, for the Kyoto project-based flexibility mechanisms to work effectively, the private sector will need to be engaged through appropriate incentives’ (UNFCCC, 1999: 6).

Since decisions taken within the experimental collective only really start to affect others when experimental creations are expanded, the process of mobilising acceptance and support for replication is a key moment in the politics of experimentation. This is where the micropolitics of experimentation turn into macropolitics. In polycentric theory, this is usually rather unproblematically referred to as diffusion and ‘upscaling’. In the following section, we take a closer look at two specific mechanisms and at how they work together.

6.4 The ‘Scaling Up’ of Experimental Results

6.4.1 Generating Epistemic Authority: Performing the ‘Representation of Nature’

A first way in which locally generated truths can expand is by gaining acceptance for the claim that they are indeed of wider validity and importance. To this end, results are formulated in abstract and general terms, as decontextualised accounts that can circulate, while linkages with the actual experiment are maintained as chains of reference. By erasing particular concerns, interactional dynamics and situational contingencies that shaped this particular process, the experimental findings are turned into neutral representations of universally given conditions of nature. As such, they appear relevant even for those who were not themselves involved in the creative production of these findings, neither taking constitutive decisions nor actually making experiences (Gilbert and Mulkay, Reference Gilbert and Mulkay1982; Shapin, Reference Shapin1984; Latour, Reference Latour1987). If the claim to represent nature becomes accepted by a wider audience, local experimental findings are vested with epistemic authority. ‘Applying’ them for a reconfiguration of collective orders elsewhere thus shifts from being a matter of trusting that decisions among experimenters also reflect one’s own values and measures of relevance into a matter of rationally coping with factual requirements.

In the process of innovating governance instruments like emissions trading (Voß, Reference Voß2007a; Simons, Lis and Lippert, Reference Simons, Lis and Lippert2014), transition management (Voß, Reference Voß2014) or methods of public participation (Voß and Amelung, Reference Voß and Amelung2016), it has been shown how the translation of findings from experiments into authoritative epistemic claims led to the establishment of facts about their functioning among a growing constituency. This is an achievement that is not necessary nor irreversible. The expert literature plays a key role here, as it establishes facts about the functionality of a general model of governance across a series of experiments (Simons, Reference Simons2015, Reference Simons, Voß and Freeman2016).

6.4.2 Generating Political Authority: Mobilising ‘Instrument Constituencies’

A second way of expanding experimentally shaped orders is by generating collective will and agency for developing experimental findings into a general instrument for solving problems of governance. In addition to generating epistemic authority, as described earlier, collective action can also be mobilised by attracting wants and desires of actors from beyond the original experimental collective. Additional actors may become enrolled for the aesthetic attraction of a world modelled after the experiment or for the expectation that it solve their own problems or otherwise benefit them, if practical efforts were undertaken to reproduce the experimental order beyond the confined setting of first trials (Akrich, Callon and Latour, Reference Akrich, Callon and Latour2002). Supporters may, for example, be recruited by raising expectations of increased demand for products and services, or of institutional authority and expert positions in fields like public administration, business, civic activism, science etc. (Voß and Simons, Reference 116Voß and Simons2014: 739). Apart from mobilising a wider array of actors, there is the challenge of orchestrating an enlarged constituency with more diverse attachments and expectations. This involves the articulation of ‘representative claims’ (Saward, Reference Saward2006) on a collective will and interest in developing the experimental configuration into an instrument. When they are adopted by constituency members, this ‘produces temporarily associated wills’ (Latour, Reference Latour2013: 133) and generates political authority to be used for legitimately articulating collective action strategies and norms.

A dedicated effort to enrol a wider set of actors for the expansion of early experiments with emissions trading can be seen in ‘Project 88’ (Voß, Reference Voß2007b; Simons, Reference Simons2015). It was initiated by committed members of an experimental collective that emerged around the first trials with emissions trading at the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in the 1970s. The project brought together spokespersons from industry and the environmental movement, from different states and from the US Republican and Democratic parties. Through a series of workshops and negotiations, it eventually produced a policy proposal supported by a widespread and influential constituency (Project 88, Reference Stavins1988). This in turn was taken up by the incoming president, and the constituency was mandated with the task to install the US Acid Rain Program as the then-largest emissions trading programme. Though the Acid Rain Program was not concerned with greenhouse gas emissions, it became a crucial stepping stone for inserting emissions trading into climate policy and expanding the constituency transnationally, such as founding the International Emissions Trading Association in 1999.

6.4.3 Co-producing Epistemic and Political Authority: ‘Realising Governance’

So far, we have highlighted various points at which politics occurs in the experimental process. Studies which follow particular models of governance along their historical pathways of development also show, however, that they become articulated over a series of different experiments (Muniesa and Callon, Reference Muniesa, Callon, MacKenzie, Muniesa and Siu2007; Callon, Reference Callon2009). Along the innovation journey of such models, one can find experiments that are geared specifically towards epistemic or political authority generation, as described earlier, and discern a ping-pong pattern in which they play together (Voß, Reference Voß2014, Reference Voß, Voß and Freeman2016). Epistemically oriented experiments gradually produce harder facts on the basis of more sophisticated models that process more data and generate increasing evidence for arguing necessities and possibilities of collective action. They are carried out by experts in the laboratory or otherwise highly controlled circumstances, and are concentrated on fact-making in support of the functionality of governance models. Politically oriented experiments are associated to them. They gradually assemble broader and more powerful coalitions for installing larger real-world cases and for funding further research efforts to draw empirical data and provide evaluations. In these experiments, the focus is on testing claims about collective interests for policy-making and reconfiguring practices out in the field. Like pistons in a reciprocating engine, both types of experiments can so work together for the ‘realisation’ of new forms of governance, both in knowing and in doing (Voß, Reference Voß2014).

Here again, emissions trading provides an instructive case. From the early 1970s until 2000, economic models and experiments ‘in silico’ have been developed in close interplay with policy coalitions and experiments ‘in vivo’ (Voß, Reference Voß2007a; Simons, Reference Simons2015). While designs and evidence of their effects were simulated in computer models, these results were taken up, for implementation, first in a tentative trial at EPA and later for the Acid Rain Program as a large-scale policy experiment. Both policy processes fed model-based experiments with data and mobilised public support for this kind of research. Epistemic and political authority in support of emissions trading were thus co-produced over a series of interconnected lab and field experiments (Voß, Reference Voß, Voß and Freeman2016).

6.5 Conclusions

We have shown that the experimental process involves several decision moments. Every decision has the effect of including and excluding, and of granting more central positions to some actors rather than others. It would be an illusion, or a tactical masking, to presume that experimenting could somehow delegate all those decisions to nature or objectify them through method.

Since there is an inescapable social component in all experimenting, we may expect established power relations to shape experimental agendas and outcomes. Studies of the actual conduct of experiments in governance testify to this point. Without any further provisions, a greater role for experimentation in the shaping of collective orders, as polycentric governance theory proposes, would allow a few already powerful actors to realise their particular visions of governance at the expense of others who do not get to test theirs. At the same time as it would provide spaces for unregulated power play, it would make politics less visible, because decisions about collective order would be displaced from political arenas to more or less closed projects in which selected experts and stakeholders negotiate the future in apparently technical terms. The neglect of politics in polycentric and experimental governance theory contributes to this.

What are we to make of this? A first point would be to be attentive to problem frames and deeper ontological presuppositions that are inscribed in experimental infrastructures. We need to have a closer look at the processes in which decisions are taken in this respect. To develop our understanding of experimentation, more detailed empirical studies are needed of how governance experiments are actually done and how politics and power play out at the micro level of social interactions within certain experimental projects. Which alternative problems, research questions, experimental designs, measurement options and interpretations of results are articulated, which ones are suppressed and how are some asserted against others? Following up on these questions would require an interpretive and practice-oriented research approach that allows for empirically tracing the negotiation of problem frames and ontological assumptions while experimental infrastructures are socially and materially configured.

A second point would be to build on such studies for explicating the politics of doing governance experiments and to start thinking about a constitution. So far, experimental politics, because of their existence in the shadow of critical analysis and public attention, allow the fittest to survive. For civilising the ‘Wild West’ of experimental politics, they would need to be turned into a public issue so that a wider discussion is opened about how they should be done and how overarching rules could be established (Thiel, Reference Thiel2016; see also Chapter 1).

Finally, what is at stake here are future world orders that are collectively to be cherished or endured by ‘the people’. This brings democracy back in. The most crucial problems of polycentric governance as currently debated and advocated are that it ignores issues of legitimacy and justice by implicitly assuming some kind of pluralistic equilibrium (see Chapters 18 and 19). Yet, as polycentric governance ‘escapes the control of nation states’ (see Chapter 1), it simultaneously escapes the constitutionalisation of politics that has been fought over for centuries. Once upon a time, only princes and bishops experimented with governance. Polycentric governance, as it stands, would just evade democratic principles and open the field for new princes and bishops to emerge, perhaps in the shape of self-appointed sustainability stewards, experts, corporations and charities. Thus a major challenge is to make sure that experimental politics receive public scrutiny and to give it a solid democratic constitution.

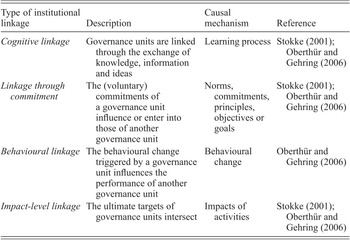

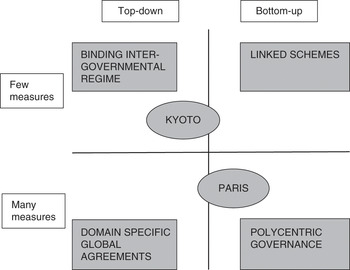

7.1 Introduction

What do investment banker Tessa Tennant, former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger, European Commission official Jos Delbeke and former London mayor Ken Livingstone have in common? They are all climate governance entrepreneurs. Drawing on academic studies of these and other entrepreneurs, this chapter argues that an entrepreneurship approach can help analysts to understand why some actors, in some situations, seem able to significantly accelerate, stall or shift climate policy and governance. Moreover, the shift towards more polycentric climate governance potentially affords governance entrepreneurs an even more important role as drivers or inhibitors of new governance developments.

Governance entrepreneurship is by no means a phenomenon that pertains only to polycentric governance. Over the years, political scientists and sociologists have explored how entrepreneurship plays out in a wide variety of contexts (e.g. Huitema and Meijerink, Reference Huitema and Meijerink2009; Green, Reference Green2014; Jordan and Huitema, Reference Jordan and Huitema2014; Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). The rapidly expanding literature on environmental and climate governance focuses on entrepreneurship at many different levels and in many different sites of governing: local and regional (Brouwer, Reference Brouwer2013; Anderton and Setzer, Reference Andonova2017; Maor, Reference Maor2017), national (Huitema and Meijerink, Reference Huitema and Meijerink2009; Boasson, Reference Boasson2015; Hermansen, Reference Hermansen2015), supranational (Buhr, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) and transnational (Green, Reference Green2014; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). This chapter seeks to add to the more nuanced picture of entrepreneurship that these authors have painted, avoiding the trap of heralding entrepreneurs as heroic figures. This chapter neither defends nor questions the development of more polycentric forms of governance. Rather, it uses polycentric governance as an explanatory concept to help explain the role of entrepreneurship in climate governance.

This chapter explores three main questions. First, how should climate governance entrepreneurship be understood, defined and operationalised? Second, to what extent and how may we expect entrepreneurship to play out in polycentric governance as compared to monocentric governance? Third, what are the potential limitations of applying an entrepreneurship lens to the analysis of climate governance?

7.2 Defining Climate Governance Entrepreneurship

Political scientists have a long tradition of studying actors that aim to achieve extraordinary things. Yet there is still confusion about what entrepreneurship actually means, how to apply it as an analytical tool in empirical research and how to perform entrepreneurship studies in a way that fosters cumulative research. Let us therefore first explore how climate governance entrepreneurship can be understood, defined and operationalised.1

Back in 1961, Dahl argued that policy entrepreneurs are especially ‘skilful or efficient in employing the political resources at their disposal’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1961: 272, emphasis in original). Polsby (Reference Polsby1984: 171) emphasised a different aspect, regarding entrepreneurs as actors ‘who specialize in identifying problems and finding solutions’. However, it was Kingdon who offered a more detailed theorisation and conceptualisation. He held that entrepreneurs are characterised by their ‘willingness to invest their resources – time, energy and sometimes money – in the hope for a future return’ (Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2011: 122).

His definition is very broad: it could conceivably apply to all actors aiming to influence policy development. Roberts (Reference Roberts1992: 56) argued that it was difficult to evaluate the state of entrepreneurship research because there was no consensus on what entrepreneurship was. This challenge persists, despite the substantial empirical and theoretical contributions published since the early 1990s. For entrepreneurship studies to prosper, it is important to develop a clearer understanding, starting with clear definitions. Various scholars define entrepreneurs by their skills. For instance, Fligstein (Reference Fligstein2001: 107) has argued that entrepreneurs are skilled societal actors who will be ‘more skilful in getting others to cooperate, manoeuvring around more powerful actors, and generally knowing how to build coalitions in political life’. In a similar way, Dahl argues that ‘[s]kill in politics is the ability to gain more influence than others, using the same resources’ (Dahl, Reference Dahl1961: 307). Fligstein, Dahl and Polsby also indicate that creativity is a key skill, because it enables entrepreneurs to find new paths to influence. The assumption that skills are the most important defining feature is intuitively appealing. Indeed, some actors are better at assessing the political context than others. Sometimes their influence may extend far beyond what could be expected on the basis of their formal position or role. One problem here, however, is that the identification of superior abilities and personal character is difficult to operationalise. How can a person’s intrinsic skills and qualities be measured? Moreover, skills are not likely to translate into actions in all situations and at all points in time. In identifying entrepreneurship, it is thus more fruitful to focus on entrepreneurial strategies and actual actions. Ackrill and Kay (Reference Ackrill and Kay2011: 78) suggest that entrepreneurship should be regarded ‘as a general label for a set of behaviours in the policy process, rather than a permanent characteristic of a particular individual or role’. Sheingate (Reference Sheingate2003: 198) actually argues that in the study of entrepreneurship, it is a mistake to focus on the personal qualities of individuals, ‘for this … limit[s] the utility of the concept to the study of “great men”’. Instead, Fligstein and McAdam (Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012) argue that the position of entrepreneur is a role that becomes available under certain social conditions. It is up to the actors involved in the process to seize the moment and exert entrepreneurship.

In this chapter, I understand entrepreneurship as acts performed by actors who seek to ‘punch above [their] weight’ (Green, Reference Green2017). By contrast, actors who merely ‘do their job’ and do what is ‘appropriate’ cannot be considered entrepreneurs. Two different categories of entrepreneurship can be identified (see Boasson, Reference Boasson2015; Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017). Institutional-cultural acts are aimed at enhancing influence by altering the distribution of authority and information. They require scholars to pay close attention to the use of decision-making procedures and venues (Roberts and King, Reference Roberts and King1991; Schneider and Teske, Reference Schneider and Teske1992; Moravcsik, Reference Moravcsik1999; Leca, Battilana and Boxenbaum, Reference Leca, Battilana and Boxenbaum2006; Hardy and Maguire, Reference Hardy, Maguire, Greenwood, Oliver, Sahlin and Suddaby.2008; Mintrom and Norman, Reference Mintrom and Norman2009; Mackenzie, Reference Mackenzie2010; Kingdon, Reference Kingdon2011; Fligstein and McAdam, Reference Fligstein and McAdam2012). By contrast, structural acts aim at altering or diffusing norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews and institutional logics. It requires scholars to explore activities such as framing, image-making and persuasion (Goffmann, Reference Goffmann1974; Snow and Benford, Reference Snow, Benford, Klandermans, Kriesi and Tarrow1988; Campbell, Reference Campbell2004; Goodin, Rein and Moran, Reference Goodin, Rein, Moran, Goodin, Rein and Moran2006; Baumgartner and Jones, Reference Baumgartner and Jones2009).

Many entrepreneurship scholars have been interested in entrepreneurship as a vehicle for change (i.e. the entrepreneur as a disruptive agent). Even if many entrepreneurial acts aim at producing change, and even if the most common criterion for successful entrepreneurship is achieving change, it is important to be open to the possibility that an entrepreneur can also block change (Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017). Moreover, given the complexity of the contemporary climate governance landscape (see Chapter 1), it is not always clear which governance measures will work and which will be counterproductive. Hence, we should include all kinds of entrepreneurial motivations when we study polycentric climate governance.

Moreover, we should take into account that governance entrepreneurship is a broader term than policy entrepreneurship. Governance covers traditional forms of public policy as well as private, and public-private initiatives aimed at influencing, steering and coordinating behaviour (see Chapter 1). Hence, entrepreneurship aimed at influencing private and public, as well as public-private, decision-making should be taken into account.

7.3 The Role of Governance Entrepreneurship in Polycentric Governance

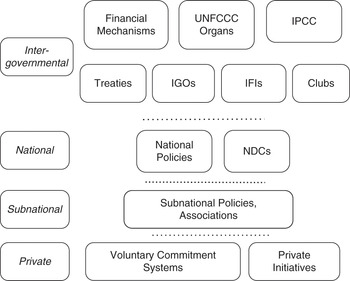

Back in 1997, many regarded the signing of the Kyoto Protocol as the first step on the path towards a monocentric global regime. Instead, climate governance subsequently adopted many more characteristics that can be described as polycentric. Changes in the basic landscape of climate governance have important implications when it comes to understanding the actual and potential roles of entrepreneurship. To shed light on this, I explore entrepreneurship under two simplified but contrasting conditions: polycentric and monocentric climate governance. Monocentric and polycentric governance differ in at least two respects (see Chapter 1):

(1) Whether steering and coordination is induced top down from global, intergovernmental agreements or bottom up from a variety of countries, sectors and domains.

(2) Whether climate mitigation relies on a few intergovernmental measures or a whole variety of measures adopted in international, transnational, national, subnational and private domains.

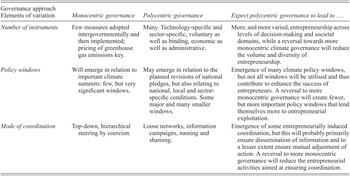

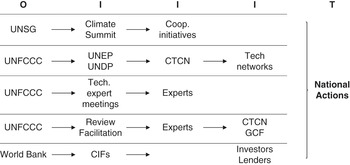

Figure 7.1 combines the two dimensions and shows that – depending on the degree of top-down steering and the number of measures in use – we are likely to find different modes of climate governance. Strong top-down steering combined with few measures and instruments would produce monocentric climate governance, while bottom-up developments combined with a great number of diverse measures and instruments would result in polycentric governance. For the sake of simplicity, I rely on the definition of polycentric governance outlined in Chapter 1.

Figure 7.1 Possible climate governance patterns.

Figure 7.1 aims to illustrate that the two dimensions (top down versus bottom up, and few versus many policies and measures) can exist in various degrees, and that polycentric governance and monocentric governing are ideal types that can guide the analysis but that will not be found as such in reality. Nevertheless, climate governance following the adoption of the Kyoto Protocol (from 1997 until around 2009) can be considered closer to the monocentric ideal than climate governance after the Paris Agreement. The Kyoto Protocol had important monocentric traits: it was based on binding commitments, targets and timetables for emissions reductions and detailed rules pertaining to collaborative efforts to reduce emissions, such as the Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation (Andresen and Boasson, Reference Andresen, Boasson, Andresen, Boasson and Hønneland2012). The Paris Agreement does away with most of these monocentric features, has weak central steering and follows a more bottom-up form of governance, in which countries make pledges to address climate change, which are subsequently subject to review (see Chapter 2).

Analytically, distinguishing between the two ideal types – polycentric and monocentric climate governance – can help us to develop more tangible expectations and predictions as to what role entrepreneurship can and will play in climate governance in the years ahead. Next, I discuss what implications these two forms of governance may have for climate governance entrepreneurship, paying particular attention to differences relating to (1) the number of measures and instruments; (2) policy windows; and (3) coordination across levels and domains.

Starting with the first of these, ever since the Kyoto Protocol was negotiated, actors that have promoted monocentric climate governance have sought to put a price on greenhouse gas emissions. I thus assume that this measure will play a superior role in this type of governance (see Andresen and Boasson, Reference Andresen, Boasson, Andresen, Boasson and Hønneland2012; Boasson and Lahn, Reference Boasson, Lahn, Wurzel, Connelly and Liefferink2016). Under more polycentric conditions, the greater willingness and ability to experiment will probably lead to multiple parallel and partly overlapping measures (see Chapters 1, 6 and 14). This will again tend to create multiple parallel and partly overlapping policy and governance patterns at different domains and at various levels (local, national, international and transnational).

The entrepreneurship literature indicates that many overlapping decision-making venues at various levels can be a valuable asset for entrepreneurs (Boasson and Huitema, Reference Boasson and Huitema2017), as it creates more entrepreneurial opportunities. One may argue that climate governance will in any event be complex – given the many sectors and actors involved in mitigating emissions – but a polycentric governance model will arguably increase this degree of complexity. I assume that polycentric climate governance will entail more, and more varied, entrepreneurship across levels of decision-making and societal domains, while a reversal towards more monocentric climate governance will reduce the volume and diversity of entrepreneurship. This assumption is rooted in existing research on how entrepreneurs respond to complexity. Newman (Reference Newman2008: 121) shows that duplication of authority structures in the European Union (EU) offers increased possibilities for societal groups to exert entrepreneurship (see also Börzel and Risse, Reference Börzel, Risse, Featherstone and Radaelli2003: 67). Mackenzie (Reference Mackenzie2010: 383), studying Australian policy development, observes that a multiplicity of policy forums in the federal political system in Australia provides ‘policy entrepreneurs with more avenues through which to pursue their innovations’. According to Sheingate (Reference Sheingate2003: 187, 191), heterogeneity creates uncertainty that can be exploited by entrepreneurs.

Indeed, scholars have increasingly identified how climate governance entrepreneurs have targeted many different venues of decision-making. Cities and states play an increasingly important role in climate governance, and several authors have argued that this is partly a result of entrepreneurship. For instance, Anderton and Setzer (Reference Andonova2017) show that entrepreneurship played a key role when São Paulo and California developed stronger climate polices. Biedenkopf (Reference Biedenkopf2017) shows that entrepreneurial governors have been instrumental in the adoption of emissions trading in several US states. Maor (Reference Maor2017) and Mintrom and Luetjens (Reference Mintrom. and Luetjens2017) show how entrepreneurial activities and strategies have resulted in transnational city climate networks.

Entrepreneurship may also play an important role in national climate policy development. For instance, Boasson (Reference Boasson2015) and Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015) explore how entrepreneurship has been key at certain moments in the development of Norwegian climate policy. Significant entrepreneurial activities have also influenced EU climate policy. Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) find that entrepreneurship has been important for the EU’s policies on emissions trading, renewable energy and carbon capture and storage. Buhr (Reference Buhr2012) shows that entrepreneurship was central for the inclusion of aviation in the EU’s emissions trading system. This literature indicates that institutional as well as structural entrepreneurship plays out at all levels. However, it is biased towards acts of entrepreneurship that seek to strengthen mitigation; it is less clear regarding how much counter-entrepreneurship (i.e. acts aimed at defending carbon-intensive practices and/or hindering the adoption and implementation of climate measures) we may see as the world moves towards more polycentric forms of climate governance.

While entrepreneurship can be a cause of polycentric development, it can also be understood as a consequence of weak monocentric steering (see also Chapter 9). Green (Reference Green2014: 16) argues that weaknesses in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) created a vacuum that allowed non-state, entrepreneurial actors to launch their own governance measures. If these experiments prove successful, they may be adopted by states. It is easier to initiate new policy ideas when no policy already exists than in a landscape crowded with other activities. In particular, scholars have highlighted entrepreneurship as an explanation for the upsurge in transnational governance (Green, Reference Green2014; see also Chapter 4). Andonova (Reference Andonova2017) explores entrepreneurship in international public-private partnerships. Pattberg (Reference Pattberg2017) shows that the entrepreneurial activities will change during the lifetime of transnational governance initiatives, and specifies what activities we may expect in different phases. There is an emerging literature on the role entrepreneurship plays in international private governance; much less is known about its role in national, regional and local private and/or private-public initiatives.

We may expect that as a more polycentric governance pattern is established, entrepreneurship may contribute to strengthen it further. After all, policies tend to determine politics (Lowi, Reference Lowi1964, Reference Lowi1972). A range of historical institutional studies have taught us that once a path of development has been created, subsequent policy tends to continue along that path (Pierson, Reference Pierson2004; Streeck and Thelen, Reference Streeck and Thelen2005). Accordingly, we may expect each of the many policies and measures adopted across scales and domains to develop along idiosyncratic paths, fostering multiple policy constituencies and decision-making venues. This will again create many opportunities for entrepreneurship, but it will become increasingly hard to know in advance which decision-making opportunities will be important. These multiple path dependencies may also contribute to hinder coherent and well-coordinated climate action (see in more detail later in this chapter).

In a monocentric regime, public decision-makers will seek to select one or a few of the best available instruments; the potentially important decision-making situations will be relatively few, and it will be relatively easy to differentiate important from unimportant decision-making opportunities. The competition for influence at these moments may, however, be very intense, so it may be harder for entrepreneurs (of all kinds) to succeed.

Second, the volume as well as the success of climate entrepreneurship is related to the existence of policy windows (e.g. Burh, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014; Hermansen Reference Hermansen2015). This is probably the single most dominant contextual condition cited in the entrepreneurship literature. Kingdon (Reference Kingdon2011: 165) regarded a policy window as ‘an opportunity for advocates of proposals to push their pet solutions, or to push attention to their special problems’. He further stated that ‘a window opens because of change in the political stream (e.g. change in the administration, a shift in the partisan or ideological distribution of seats in Congress, or a shift in national mood); or it opens because a new problem captures the attention.’ A substantial number of subsequent studies have shown that open policy windows permit enhanced entrepreneurial activities and sometimes also entrepreneurial success (e.g. Corbett, Reference Corbett2005; Ugur and Yanjaya, Reference Ugur and Yanjaya2008; Bakir, Reference Bakir2009; Zito, Reference Zito2011).

In the following, I argue that polycentric climate governance will tend to entail the emergence of many climate policy windows, but not all windows will be utilised and thus contribute to the success of entrepreneurs. In more monocentric forms of governance, there will be fewer but more important policy windows that lend themselves to entrepreneurial exploitation. Climate policy research shows that open policy windows have made climate policy and governance entrepreneurs more successful than they would have been without such a window. For instance, Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014) identify an open climate policy window in the EU from about 2006 to 2009, created by the preparations for the 2009 UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) in Copenhagen. Many actors in several different climate policy areas seized this opportunity. This had implications not only for EU policy but also for national policy in the EU; however, we lack systematic research on how this window influenced national policy development (for an exception, see Hermansen Reference Hermansen2015). Moreover, Boasson and Wettestad (Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014), as well as Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015) and Buhr (Reference Buhr2012), argue that policy windows are not merely a result of exogenous forces; entrepreneurs themselves seek to open windows and subsequently to keep them opened for as long as possible. Hermansen (Reference Hermansen2015: 933) argues that ‘[a] political wave comes from somewhere and involves some form of agency; it does not just appear out of the blue.’ Several authors have shown that institutional-cultural entrepreneurship and framing is key when it comes to the very creation of windows (Buhr, Reference Buhr2012; Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014; Hermansen, Reference Hermansen2015). Structural entrepreneurship can be important to prolong the period the window is open (Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2014).

Preparations for important UNFCCC COPs (such as COP15 in 2009 and COP21 in 2015) create more important domestic policy windows in some countries than in others, but we have little systematic and comparative research on this (but see Chapter 3). We also lack systematic knowledge about the relative importance of policy windows in private or private-public governance processes. Existing research indicates that such windows primarily strengthen the positions of actors that champion more and stronger climate polices. This may, however, result from a research bias, as there are far fewer studies that analyse actors who seek to obstruct climate policy initiatives (for an exception see Kibaroglu, Baskan and Alp, Reference Kibaroglu, Baskan, Alp, Huitema and Meijerink2009).

There are good reasons to expect that the character and volume of potential policy windows will differ between polycentric and monocentric climate governance, and work on Chinese policy change processes (te Boekhorst et al., Reference te Boekhorst, Smits and Yu2010) lends support to this notion. A centralised system will probably produce rather few, but potentially more important, policy windows. The fact that national climate policy adoptions tend to peak in the year or two before and after major global climate summits, such as those held in Rio de Janeiro (1992), Kyoto (1997) and Copenhagen (2009), indicates that intergovernmental summits help to create windows of opportunity that entrepreneurs can exploit (Townshend et al., Reference Townshend, Fankhauser and Ayabar2013). However, it is important to acknowledge that a range of other factors may also have contributed to producing this pattern. The future regular ‘global stocktakes’ of the nationally determined contributions under the Paris Agreement may ensure that the global regime continues to open up policy windows. If the ratcheting-up logic works, then the five-year cycle of ‘pledge and review’ could create regular, global policy windows. Moreover, increasingly polycentric governance patterns will probably ensure that many more policy windows are opened across decision-making levels and domains, created by local and regional conditions, sector-specific conditions, summits held by non-state actors and so forth. Yet, it may be that these policy windows will be less dramatic and be open for shorter periods than the windows relating to major intergovernmental summits. Moreover, this development may also reduce the importance of UNFCCC COPs as events that create windows of opportunity.

In any event, it is important to acknowledge that not all actors will be able, or have the resources required, to understand that a window has opened, and thus not all windows will be exploited to the same extent. Mintrom and Norman (Reference Mintrom and Norman2009: 852) argue that entrepreneurs need to ‘display high levels of social acuity, or perceptiveness’ to exploit such windows. Such actors are not always around, and thus only some of the ensuing political potential will be tapped (Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). Moreover, polycentric governance creates a more murky political landscape that may make it harder for entrepreneurs to detect, trigger and influence policy windows. Hence, the growth in the number of potential policy windows under polycentric conditions may not necessarily translate into more successful climate policy entrepreneurship and hence more ambitious climate policies.

Third and last, coping with climate change is a true global challenge, and thus we need a certain degree of coordination in order to solve the issue effectively and efficiently. The polycentric and monocentric models of governance rely on different modes of cooperation. The polycentric approach highlights self-organisation or mutual adjustment, often resulting from mere interaction and learning (see Chapter 1). By contrast, coordination in the more monocentric approach relies on what Scott (Reference Scott2014: 59–64) terms regulative steering: hierarchically designed, formal requirements that prescribe how information is to be disseminated and compliance monitored. There are also likely to be coercive sanctions to address any shortfalls in compliance. I argue that while coordination in the monocentric approach relies on intergovernmental political agreement and the agreed system of enforcement, coordination in a polycentric governance system is more reliant on entrepreneurship.

Coordination will not be a task that gains much entrepreneurial attention in monocentric governance. Rather, this will primarily be ensured by top-down steering. The situation is likely to be radically different in polycentric governance. For coordination mechanisms to emerge in the first place, these will need to be initiated and developed by actors other than the intergovernmental regime. Some of the polycentric governance authors suggest that mutual adjustment is a key feature of polycentricity, but I do not a priori assume that this will occur (see Chapter 1). Rather, I expect climate governance entrepreneurs to primarily mobilise to influence development of rules and practices, and to a lesser extent engage to ensure adjustments of measures across levels and domains.

The pledge-and-review system introduced by the Paris Agreement combines polycentric and monocentric governance elements (see Chapter 2). It requires countries to regularly submit a nationally determined contribution, but it is largely up to the countries to set their own ambitions and choose their own reporting format. Thus, it is a relatively weak top-down steering mechanism, ‘creating a framework for making voluntary pledges that can be compared and reviewed internationally, in the hope that global ambition can be increased through a process of ‘naming and shaming’ (Falkner, Reference Falkner2016: 1107). Whether this will develop into a system that truly facilitates behavioural change depends on whether and how country representatives, business actors, international environmental organisations and so forth respond to it. Put differently: whether actors will engage in entrepreneurial ways to ensure a ‘race to the top’.

The radical increase in private carbon disclosure can be understood as an entrepreneurially induced attempt to increase climate information sharing, particularly amongst private actors (Maor, Reference Maor2017; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). Carbon disclosure implies carbon reporting which denotes reporting of carbon emissions by companies, but also a broader societal purpose, increasingly understood as an instance of informational governance (Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). Hence, mechanisms of transparency and accountability may eventually influence the behaviour of actors, leading to processes of mutual adjustment. Pattberg (Reference Pattberg2017) shows that while several carbon disclosure systems initially resulted from entrepreneurship, the activity has since become institutionalised. This indicates that coordination under polycentric governance can eventually be sustained by institutional-cultural social features, and is not completely reliant on entrepreneurship. It is, however, important to note that while disclosure may ensure that information is disseminated, actual behavioural change may not happen unless some actors use the information that is disclosed in an entrepreneurial way, for instance to nudge or pressure other actors to adjust their behaviour. Moreover, we have not (yet) witnessed such elaborate systems of carbon reporting from governmental units, such as municipalities, regions and countries (with the notable exception of the C40 reporting from cities). The pledge-and-review system under Paris may, however, trigger the emergence of more streamlined pledge-and-review procedures from a larger number of actors.

Finally, there is reason to expect that it will be challenging to ensure coordination in a polycentric system given the ‘let a thousand flowers bloom’ nature of bottom-up governance. Many initiatives can sometimes be good, but it may also hamper effectiveness and efficiency. There is indeed a danger that having too many cooks involved in polycentric climate governance can spoil the broth. That is to say, the more actors that have authority over an issue area, the harder it may be to ensure coordination (Gulick, Reference Gulick, Gulick and Urwick1937; Egeberg, Reference Egeberg, Peters and Pierre2003).

Against this backdrop, I assume that polycentric climate governance may entail emergence of entrepreneurially induced coordination, but that this will probably primarily ensure the dissemination of information and to a lesser extent ensure mutual adjustment of action. A reversal to more monocentric governance will reduce the entrepreneurial activities aimed at ensuring coordination.

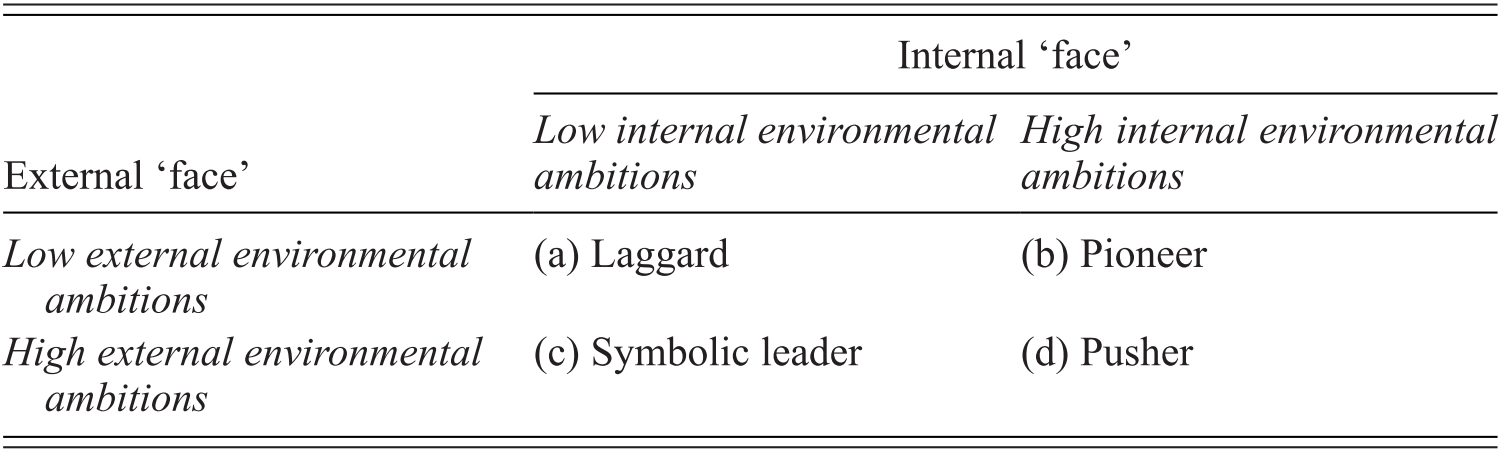

Table 7.1 summarises the differences between the nature and volume of entrepreneurial activities under the two governance modes. We should expect entrepreneurship to be a more important driver of climate action in a polycentric than in a monocentric climate governance situation, but also that entrepreneurship will take on different roles depending on which form of governance dominates. However, entrepreneurship is a rather quixotic factor – one that is highly dependent on a range of other variables. As not all entrepreneurs will be interested in more ambitious climate rules and practices, more room for entrepreneurship also means more room for actors aiming to resist climate governance.

7.4 The Role of Entrepreneurship in Climate Governance Studies

Thus far, I have argued that we should expect to see systematic differences in the role and magnitude of entrepreneurship depending on the type of climate governance mode. However, it is important to keep in mind that entrepreneurship is only one piece of the climate governance puzzle. There are clear limitations of applying an entrepreneurship lens to the assessment of climate governance.

Few studies have examined how entrepreneurship will fare when challenging powerful segments or sectors in society. It is, however, not very daring to suggest that entrepreneurship will have a smaller chance of succeeding when challenging economically and/or politically powerful actors. Social scientists that only focus on entrepreneurship may easily overlook entrenched power relationships relating to economic as well as social and cultural sources of influence. Wilson (Reference Wilson1989: 77) suggested that entrepreneurial action is key to ensuring environmental regulation, arguing that the cost of mitigating most environmental issues will be ‘heavily concentrated on some industry, profession, or locality and the benefits are spread over many if not all people’. He argued that the actors that experience costs relating to environmental action will mobilise all the political powers at their disposition to oppose these measures, while those in favour of a cleaner environment will tend to only overcome collective action dilemmas when they perform skilled entrepreneurship. Moreover, while such entrepreneurship can be very important in certain decision-making situations, it will often be challenging to create a long-lasting entrepreneurial counterweight to stronger social forces (Wilson, Reference Wilson1989: 80).

In addition to the economic interests highlighted by Wilson, several other factors may also counter the effect of entrepreneurship. Entrenched institutional-cultural features, for instance relating to energy use, modes of transportation (‘car culture’) or dietary habits (i.e. meat consumption), may thwart the adoption of stronger climate practices and governance. Moreover, public administrative units and businesses that have little to gain from climate mitigation often have superior formal authority and the ability to control information. For instance, a study of carbon capture and storage in the Norwegian petroleum industry shows that scientists, environmentalists and politicians succeeded only to a very limited degree, despite having applied a whole range of entrepreneurial strategies. The resistance from the structurally powerful petroleum segment was too strong (Boasson, Reference Boasson2015). This created a paradox: since it took more to succeed when the resistance was strong, entrepreneurs ended up being very active when they encountered strong opposition, while paying little attention to areas where the potential counterforces were much weaker. Thus, many opportunities remained unexploited.

Despite this bleak example, other parts of the climate entrepreneurship literature show that entrepreneurship can have long-lasting effects, and this gives us reason to be a bit more optimistic than Wilson (e.g. Boasson and Wettestad, Reference Boasson and Wettestad2013; Biedenkopf, Reference Biedenkopf2017; Green, Reference Green2017; Pattberg, Reference Pattberg2017). To understand the potential expansive effects of entrepreneurship, we need to combine the entrepreneurship approach with other social science frameworks and theories. Green (Reference Green2017) argues: ‘Considering the expansive effects of entrepreneurship means looking beyond the specific goal or target of an individual entrepreneur. Rather, it examines the extent to which entrepreneurship influenced a larger set of actors than originally intended, or helped catalyze broader effects.’

Drawing on various social science literatures, Green highlights three types of expansive effects. First, demonstration effects, where entrepreneurs, perhaps through forms of experimentation, ensure that some climate action is tested. When an action has been proven to work, this will help make the measure more legitimate. Second, policy entrepreneurship might give rise to normative changes. For instance, we have seen that entrepreneurship related to carbon disclosure has contributed to a broader corporate norm of more transparent measurement and reporting. Third, entrepreneurship might have the expansive effect of changing governance practices, leading governments to align with or adopt practices initiated by entrepreneurs. It can be challenging to determine analytically when the effects of entrepreneurship end and other causal forces take over, but skilful combinations of different theories and frameworks can help us capture important expansive and long-term effects of entrepreneurship.

To gain a better understanding of the role of entrepreneurship under polycentric climate governance, we need more cumulative and comparative research. Hopefully, the increased interest we have seen in entrepreneurship in the area of climate governance will lead more scholars to base their research on similar understandings of this concept, enabling us to contrast how entrepreneurship may play out under different conditions and the short- as well as long-term effects of entrepreneurial activities.

7.5 Conclusions

Drawing on policy, governance and institutional entrepreneurship literatures, this chapter concludes that entrepreneurship should be understood as acts performed by actors who seek to ‘punch above their weight’. By contrast, actors who merely ‘do what is appropriate’ should not be considered entrepreneurial. Two different, more operational categories of entrepreneurship were identified: institutional-cultural entrepreneurship, understood as acts aimed at enhancing governance influence by altering distribution of authority and information; and structural entrepreneurship, understood as acts aimed at altering or diffusing norms and cognitive frameworks, worldviews or institutional logics.

This chapter has explored when – and to what extent – entrepreneurship plays out in conditions of polycentric and monocentric climate governance respectively. The upshot is that the role and importance of entrepreneurship will probably differ between polycentric governance and monocentric governance; entrepreneurship will probably be a more important driver of climate action in polycentric than in monocentric climate governance situations. We will also rely on entrepreneurship to ensure a broader range of tasks in the former than the latter governance mode. Moreover, entrepreneurship is a rather quixotic and unpredictable causal factor – whether entrepreneurship will be performed is not only a result of the prevailing mode of governance. It depends on the skills and experience of the persons involved, but other factors may be just as important, such as the distribution of economic and structural resources and prevalent institutional-cultural understandings. Ideally, research on climate governance entrepreneurship should combine this analytical lens with analytical frameworks that highlight other causal factors, such as path dependency, exogenous shocks, socialisation and diffusion.