1. Introduction

Modern Ch'ol varieties exhibit two very interesting examples of metathesis in the terms 7ehk'ach ‘fingernail, claw’ and 7ik'oty ‘with’, both of them already noted by Hopkins et al. (Reference Hopkins, Guzmán and Josserand2008). That metathesis has taken place in Ch'ol is clear from the comparative and historical linguistic data (Table 1), which shows that these Ch'ol forms stem from Proto-Ch'olan *7ihch’äk (~ *7ehch’äk) ‘fingernail, claw’ and *7et'ok ‘companion; with, and’ (Kaufman and Norman Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984: 119, 138), respectively. An important fact is that Ch'ol attests to variation in the forms 7ik'oty ~ 7ity'ok, a matter that is considered in this article. Hopkins et al. (2008: 89) also highlight an interesting aspect of these examples of metathesis, namely, that “in both these examples, the glottalization has stayed in the same position in the word while the consonants have metathesized: ch’-k to k’-ch and t’-k to k’-t.” Those authors suggest that both cases of metathesis must have occurred after the 18th century, as a Ch'ol vocabulary from 1789, published just over a century later by the sons of its discoverer at the Archivo de Indias in Seville, Spain (Fernández Reference Fernández1892), does not attest to them.

Table 1: Comparative Ch'olan data for ‘fingernail, claw’ and ‘companion; with, and’ after Kaufman and Norman (Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984) and Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003)

These cases of metathesis are phonologically interesting for two reasons. First, in both cases the glottal stricture of the medial consonant has remained in place, as observed by Hopkins et al. (2008: 89–90), and it is only the oral features of the consonants that have undergone metathesis. But this need not be the case with metathesis in the Ch'olan (or other Mayan languages), generally speaking. For example, the Greater Tzeltalan term for ‘to point out, to show’ is reconstructed to Proto-Tzeltalan as *ch'ut, but to Proto-Ch'olan as *tuch’, both from Proto-Central Mayan *k'ut, by Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003: 706), showing that metathesis can apply to “whole” consonantal segments, ejective (with glottal stricture) and otherwise.Footnote 3

To my knowledge, no other roots in Ch'ol have experienced a similar metathesis to what is seen in the forms for ‘fingernail, claw’ and ‘with’.Footnote 4 Nor do Hopkins et al. (Reference Hopkins, Guzmán and Josserand2008) offer an explanation for the process in these cases. It would appear at first glance that these two cases are isolated instances of irregular, sporadic change. But this is perhaps a narrow perception, one that can be broadened when more data are considered, and also when cross-linguistic tendencies in the application of regular metathesis are taken into account (Ultan Reference Ultan and Greenberg1978, Hock Reference Hock1985, Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Joseph and Janda2005, Bybee Reference Bybee2015). And this is where the second point of special phonological interest can be raised. When additional data in the form of other disyllabic roots and stems containing a medial /C’/ are considered, the unusual behaviour of ‘fingernail’ and ‘with’ ceases to seem unusual, but instead rather conformist: these cases of metathesis can be shown to be a response to a tendency apparent in Ch'ol, and perhaps in Mayan languages more generally, on the preferred location within a disyllabic word for an ejective or implosive segment, and on the preferred place of articulation of said segment. Thus, the data will show that the predominant pattern of disyllabic roots can be a strong force that leads speakers to certain changes.

I begin with some background to Mayan languages and Ch'ol in particular (section 2). Then I provide a brief review of scholarship on the nature of metathesis, highlighting Hock's (Reference Hock1985) “structural purpose” motivation and Hume's (Reference Hume2004) indeterminacy/attestation approach (section 3). I continue with a presentation of relevant data and a review of the etymologies, offer an explanation of the cases of metathesis in Ch'ol (and potentially Mayan languages more generally) that posits a tendency for the medial ejective in disyllabic roots of the shape /CVC'VC/ to be the backmost in place of articulation, and provide preliminary support for this hypothesis based on the investigation of a small corpus of texts for token frequencies of the relevant structures and an investigation of type frequencies in a dictionary (section 4). Finally, conclusions are presented, and future steps to further test this proposal are outlined (section 5).

2. Background and sources of data

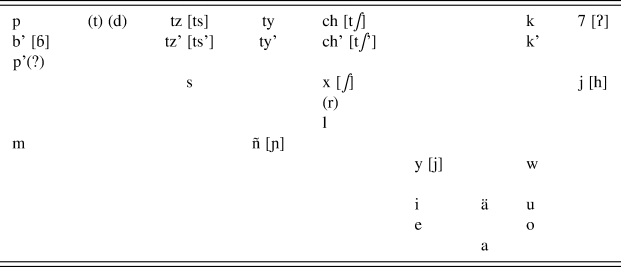

Figure 1 shows Kaufman's (Reference Kaufman, Aissen, England and Maldonado2017) model for the diversification of the Mayan languages. Of relevance for this article, it is necessary to highlight the diversification of the Ch'olan languages into two branches, an Eastern Ch'olan branch consisting of Ch'olti’ and Ch'orti’, and a Western Ch'olan branch consisting of Ch'ol and Yokot'an/Chontal; the recent ancestor of Yokot'an/Chontal is known as Acalan, based on a manuscript dating to the early seventeenth century (Smailus Reference Smailus1975). Table 2 provides the basic phonemic inventory for both Proto-Ch'olan (Kaufman and Norman Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984: 84–89), and Table 3 does the same for Ch'ol (Attinasi Reference Attinasi1973: 75, Becquey Reference Becquey2014: 93–94).

Figure 1: Diversification model of Mayan languages by Kaufman (Reference Kaufman, Aissen, England and Maldonado2017).

Table 2: Proto-Ch'olan phonemic inventory in standard orthography used in this article; IPA equivalents are provided within [].

Table 3: Ch'ol phonemic inventory in the standard orthography used in this article; IPA equivalents are provided within []. () is used for phonemes borrowed from Spanish. /w/ is labiovelar.

It is worth noting that Ch'ol has inherited CVC and CVjC canonical shapes from Proto-Ch'olan *CVC (< Proto-Mayan *CVC, *CVVC, *CV7C) and *CVhC (< Proto-Mayan *CVhC, *CVSC, with *S = /s x j/). Whether shapes like /C1VjC2/ (e.g., Ch'ol 7ejk'ach ‘fingernail, claw’) are considered as made up of a C1 onset, a Vj nucleus, and a C2 coda, or alternatively, a C1 onset, a V nucleus, and a jC2 coda, will be of no consequence in this article. Syllabification typically follows the following patterns: 7i.xik for 7ixik ‘woman’, yej.k'ach for y-ejk'ach ‘his/her/its fingernail/claw’. Complex syllable onsets (C1C2) are only allowed when they involve morpheme boundaries (i.e., with prefixes such as x- ‘female/small’, or the ergative/possessive pronominals).

To investigate the cases of metathesis of interest here, as well as the structural constraints that might have promoted them, I collected data from several sources: Kaufman and Norman (Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984) for comparative Ch'olan and Proto-Ch'olan, Keller and Luciano (Reference Keller and Plácido1997) for Yokot'an/Chontal, Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003) for comparative Mayan and Proto-Ch'olan, Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009) for Ch'ol, and Hull (Reference Hull2016) for Ch'orti’. I also employed a small corpus of texts titled “Ch'ol Texts of the Supernatural” (Whittaker and Warkentin Reference Whittaker and Warkentin1965).

3. Regular metathesis

Together with dissimilation, metathesis has been shown to be somewhat restricted in its regularity and scope when compared to sound changes like assimilation and reduction; also, like dissimilation, metathesis tends to reuse already existing segments of the language, to be phonetically abrupt rather than gradient, and to exhibit a language-specific directionality (see Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Joseph and Janda2005, Bybee Reference Bybee2015: 70–73).

Regarding the difference between regular and sporadic metathesis, Hock (Reference Hock1985: 537) argued that “metathesis can become regular only if it serves a specific structural purpose.” Such a purpose could include the promotion of open syllables in South and West Slavic via the ‘liquid metathesis’ process (e.g., Proto-Slavic *gor.dŭ > gro.dŭ/gra.dŭ ‘city’) (Hock Reference Hock1985: 532–533). It could also involve the elimination of “phonologically or perceptually ‘marked’ structures into more acceptable ones,” with markedness defined cross-linguistically, as in the case of “dental stop + l clusters” that “are frequently eliminated in the world's languages, especially if tautosyllabic,” as in the history of Spanish (e.g., Latin titulum: *tidle > Old Spanish tilde ‘title’, etc.) (Hock Reference Hock1985: 533). Regular metathesis, according to Hock (Reference Hock1985: 535), may also serve to promote a preferred syllable structure, such as a configuration of “fricative + stop” in syllable onsets, as in the history of Greek (e.g., Proto-Greek *dyēus > *dzeus > sdeus [zd-] ‘Zeus’, *dyugon > *dzugon > sdugon [zd-] ‘yoke’). And last, for our purposes, Hock (Reference Hock1985: 536) explains that it is possible for a structurally-motivated metathesis to be analogically extended to environments where it was not originally so motivated, and in fact, to lead to marked structures that may be “fixed up” by means of other processes subsequently: he notes that in “Persian (and many other Modern Iranian dialects)” a process of obstruent/nasal + liquid metathesis took place word-finally, but that one variety in particular, Ossetic, apparently extended the process from word-final (e.g., (*)caxr(a) > calx ‘wheel’) to word-initial (e.g., (*)tray(a) > ä-rtä ‘three’) contexts, resulting in marked onset structures, and as a result, a prothetic vowel was needed.

Blevins and Garrett (Reference Blevins and Garrett1998) depart from the view that metathesis is deviant compared to other sound changes, exhibiting regularity only under very specific structural conditions. Focusing primarily on CV/VC metathesis cases (in either direction), their analysis would suggest that all cases of metathesis “have basic commonalities in their diachronic phonetic basis.” They distinguish two basic types of CV/VC metathesis: perceptual and compensatory:

1) Perceptual metathesis involves only limited sets of segments; is characterized by phonetic features that can durationally transcend a segment (labialization, aspiration, retroflexion, pharyngealization, glottalization, place of articulation); may show symmetry, both language-internally and across languages; and is related to some kinds of vowel epenthesis and long-distance movement.

2) Compensatory metathesis “affects all or most” segment types, results from prosodic conditioning (such as stress and tonic length) and phonetic factors regarding the overall presence or absence of certain vocalic and consonantal traits that promote co-articulation effects.

Hume (Reference Hume2004) proposes that phonetic factors and the frequency of sound patterns in a particular language are both important considerations in metathesis, especially with cases of symmetrical metathesis, that is, cases where “two elements can surface in one order in one language but in precisely the opposite order in another language” (Hume Reference Hume2004: 206). She argues that “at the heart of the proposed account is the assumption that an individual's knowledge of his/her language, including its patterns of usage, is an effective predictor of the direction of metathesis,” and also that neither the phonetic factors nor the frequency of sound patterns alone “is sufficient to provide a fully predictive account,” but instead, both factors must be considered (Hume Reference Hume2004: 210). For example, Hume (Reference Hume2004: 205) illustrates different patterns in Pawnee and Hungarian for the cases of adjacent /r/ and /h/: in Hungarian, a phonemic sequence /rh/ surfaces as [hr], while in Pawnee, a phonemic sequence /hr/ surfaces as [rh]. She cites the “observation that the input order in each case is a nonoccurring or infrequent sequence in the language” (Hume Reference Hume2004: 217). Hume (Reference Hume2004: 217) explains thus:

Listeners learn to focus on meaningful cues in the signal, and to ignore others. Consequently, if the order of sounds in the input is unfamiliar to the listener, he/she may not be tuned to the cues that can aid in identifying the sound combination. We then correctly predict that listeners with different native-language backgrounds will process sound combinations differently if in one language the sequence occurs while in the other it does not. Yet, familiarity need not be considered all or none. Consistent with psycholinguistic studies, the listener is biased to parse the signal in a manner consistent with the most robust or frequent pattern in cases in which both orders of a given sequence occur in a language.

Based on her database and specific discussions of case studies, Hume (Reference Hume2004: 229) posits two preconditions for metathesis:

First, there must be indeterminacy in the signal, and second, the structure that would result from metathesis must already be attested in the system. Indeterminacy sets the stage for metathesis, and a speaker/hearer's knowledge of the sound system and its patterns of usage influence how the signal is processed and, thus, the order in which the sounds are parsed. The greater the indeterminacy, the more the speaker/hearer must rely on native-language knowledge to infer the temporal ordering of the sounds.

Below, I offer only a basic assessment as to the applicability of these various approaches to metathesis to the Ch'ol examples. More specifically, I attempt to test the attestation hypothesis by Hume, and whether such approach provides evidence for a structural motivation of the types suggested by Hock.

4. Analysis

Before exploring the factors that may underlie the two cases of metathesis of interest here, an excursus into their etymologies and histories, especially that of *7et'ok, could prove insightful. The etymology of ‘fingernail, claw’ is unproblematic, in as far as it can be traced back to Proto-Mayan *7iSk'aq, where *S = /h j x s/, and cannot be analyzed morphologically.Footnote 5 Classic Mayan texts attest to the spelling yi-ch'a-ki (Stuart Reference Stuart1987) for y-ihch'ak ‘his/her/its fingernail/claw’.Footnote 6 Since both Eastern Ch'olan (Ch'olti’, Ch'orti’) and Western Ch'olan (Ch'ol, Yokot'an/Chontal) attest to the variants *7ihch'ak (Yokot'an/Chontal, Ch'olti’) and *7ehch'ak (Ch'ol, Ch'orti’), the Classic Mayan spelling yi-ch'a-ki points to a retention of Proto-Mayan *7iSk'aq following the Greater Tzeltalan *k’ > ch’ and *q > k shifts, and a specific form of S as *h.

Regarding Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok ‘partner, companion; with’, the details are not as straightforward. It is almost certainly a compounded term based on the bound root for ‘partner’ or ‘fellow/mate’, which is widely attested in Mayan languages and reconstructed by Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003: 1520) as Proto-Mayan *7ety= ~ *7aty=. More specifically, they reconstruct a term *7et=’ok [sic], transcribed as *7et=7ok for consistency here, to Lowland Mayan, as seen in Table 4; I have incorporated the Acalan form, <ithoc>. This means that the term very likely diffused in the context of this contact region.

Table 4: Data pertinent to etymology of Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok (Kaufman with Justeson Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003: 1522).

Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003: 1522) do not offer an etymology for the second term of the compound, =7ok, which triggers glottalization of the /t/ of *7et= in the Lowland Mayan languages (Ch'olan, Yucatecan). An obvious candidate would be a reflex of Proto-Mayan *7ooq ‘foot/leg’, which became *7ook in Proto-Yucatecan and *7ok in Proto-Ch'olan, given that the lexical meaning of Lowland Mayan *7et=7ok is ‘companion, friend’ (i.e., someone that walks along with another). Previously, in her discussion of the Classic Mayan yi-ta-ji spelling, which likely includes the root -it= ‘partner/fellow’, MacLeod (Reference MacLeod and Wichmann2004: 301) mentions the relational noun y-it'ok, and suggested “(literally ‘its foot-fellow’)” as its etymology, but did not elaborate or justify it, to which I turn now.Footnote 7

First, several Greater Q'anjob’alan languages support this proposed etymology, such as Q'anjob’al y-et-oq ‘with him/her/it’ (Kaufman with Justeson Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003: 1522), showing a form -oq that would support an origin in *7ooq ‘foot/leg’.Footnote 8 From ‘companion’, a lexical meaning that is preserved in Ch'olti’, Ch'orti’, and Itzaj, the term underwent grammaticalization into a relational noun ‘with (comitative case); and (conjunction)’ in Western Ch'olan (Ch'ol, Acalan, Yokot'an/Chontal). In fact, the Western Ch'olan data suggest that both its grammaticalization and the change in the first vowel (Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok > Proto-Western Ch'olan *7it'ok, e.g., Ch'ol as 7ik'oty and Acalan <yithoc>), constitute Western Ch'olan innovations. After the breakup of Western Ch'olan, and in fact after 1789, as Hopkins et al. (Reference Fox2008) observe, Ch'ol experienced metathesis in this term (7ik'oty). Importantly, Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009: 123) remark that -ity'ok remains a “variant” of -ik'oty in contemporary Ch'ol, a statement that suggests that -ik'oty is the most frequent variant. Also, after the breakup of Western Ch'olan, Yokot'an/Chontal experienced the phonetic reduction and further grammaticalization of this relational noun into a preposition (y-it'ok > t'ok). The fact that Ch'orti’ and Ch'olti’ only attest to the ungrammaticalized use of this term could suggest that the Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok may have been simply ‘companion’, and that it was Western Ch'olan that innovated its grammaticalized use of ‘with’, and later, in Yokot'an/Chontal, ‘and’.

An interesting result from this etymological excursus is the conclusion that the medial /t’/ is not original in this root, but the accidental result of compounding, followed by amalgamation, of a root ending in /t/ with another root beginning in /7/. This is a relatively common result of compounding in Mayan languages, Ch'ol included.Footnote 9 Also, the evidence suggests that Proto-Ch'olan may not have yet shown evidence of grammaticalization of 7et=7ok > 7et'ok as a relational noun, but that it was instead the Western Ch'olan branch that experienced this change, with Eastern Ch'olan retaining the ungrammaticalized Proto-Ch'olan meaning only.

It is now time to examine the different types of data needed to assess whether there are analogical, regularizing factors at play in the cases of metathesis of relevance here. Appendix 1 presents a list of all the Proto-Ch'olan disyllabic roots with and without a medial /C’/; Appendix 2 sorts them by their medial consonant; and Appendix 3 sorts them by their final consonants. I have sorted the disyllabic forms in Table 5 according to the medial consonant, C2. Table 5 presents all of the disyllabic roots that can be traced back to Proto-Ch'olan that contain a medial /C’/; this dataset includes also all of the disyllabic roots in Ch'ol with a medial /C’/. Most of these disyllabic forms are essentially roots in today's Ch'olan languages, but several likely include fossilized derivational suffixes; only a few can be traced back to earlier (Pre-Ch'olan, Proto-Mayan) disyllabic roots without (obvious) evidence of compounding or derivational suffixes (e.g., #2, #4, #10, #16, #27, #28). Six Proto-Ch'olan items, #9, #13, #14, #16, #22, and #25, are not attested in contemporary Ch'ol. Furthermore, items #3 and #18 in contemporary Ch'ol preserve only the root, missing what must have been (unproductive?) derivational suffixes in Proto-Ch'olan; for the purposes of this article, these items are monosyllabic in contemporary Ch'ol and must be excluded from comparison. Items #30 and #31 are the focus of this article.

Table 5: Proto-Ch'olan disyllabic forms with medial /C’/ (Kaufman and Norman Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984; Kaufman with Justeson Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003). Abbreviations: pM = Proto-Mayan, pCM = Proto-Central Mayan, WM = Western Mayan, LL = Lowland Mayan (diffusion zone), GLL = Greater Lowland Mayan (diffusion zone), Yu = Yucatecan.

In the C1VC’2VC3 structures listed in Table 5, only eight (#4, #5, #9, #16, #24, #25, #30, #31) include a non-glottalic C1 or C3 with a glottalic counterpart in the language. None include more than two glottalic consonants: either C1 and C2 are glottalic, or C2 and C3 are glottalic, but there are no cases of both C1 and C3 being glottalic within the same root or stem. And there are no instances of two ejectives with different places of articulation: the only two examples with two ejectives (#17 and #26) show identical ejectives; otherwise, if two glottalic consonants are present in the disyllabic form, one is the bilabial implosive and the other is an ejective with different oral articulation (i.e., *b’ and *p’ do not co-occur within the same disyllabic form). I return to this last observation below, with respect to earlier stages of Mayan. Syllabification of such shapes, indicated by a period, usually follows a CV.C'VC pattern, though addition of a (typically -VC) suffix to this structure, (i.e., /CV.C'V.C-VC/), may result in a [CVC’.CVC] syllabification, after syncope of the second vowel — this process could be the cause of the reduction of #3 and #18 in Ch'ol, and can be seen, with reduction of the second vowel, in #19.

Next, attention must be drawn to the general structure of disyllabic roots and stems, particularly those glottalic and non-glottalic obstruents. One might ask, for instance, why did Proto-Ch'olan *7ihch'ak ~ *7ehch'ak not metathesize into Ch'ol 7ejkach’, and why did Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok not metathesize into Ch'ol 7ekoty’? Based on the more comprehensive dataset of di- and trisyllabic forms (Appendices 1–3), Table 6 summarizes the frequencies for the various obstruents, both glottalic and their non-glottalic counterparts. Note that /k/ and /k’/ constitute the majority of medial obstruents in such forms, with 50% of the total between them; /ch/ is found in just two cases, /ch’/ in one (‘fingernail’), while /t/ is found in eight instances and /t’/ in two; /b’/ takes up 15% of the total, while /p/ takes up 5% and /p’/ 0%. Importantly, 46.73% of all the medial obstruents are glottalic, and when we exclude the bilabial implosive, 31.73% of the medial obstruents in disyllabic forms are ejectives, and as already noted, 21.7% of all medial obstruents constitute cases of /k’/. Thus, even though glottalic obstruents do not make up the majority of medial obstruents in disyllabic forms, /k’/ makes up 21.7% of all medial obstruents, glottalic or otherwise, following only /k/ with 28.6%.

Table 6: Proto-Ch'olan frequencies of medial obstruents in CVCVC forms.

Table 7 provides the frequencies of obstruents, glottalic and non-glottalic, in the final position of disyllabic forms. Note that while glottalic obstruents make up 42.22% of all obstruents in final positions in disyllabic forms, this load is largely carried by /b’/, the implosive, with 31.12% of the total number of obstruents in final position. As far as the ejectives are concerned, there are no cases with final /tz’/, and the remaining ejectives are attested in very few examples each, with /k’/ showing up in final position in two instances out of 45 disyllabic forms with final obstruents.

Table 7: Proto-Ch'olan frequencies of final obstruents in CVCVC forms.

What the data summarized in Tables 6 and 7 suggest for ‘fingernail’ is the following: given the choice between metathesizing Proto-Ch'olan *7ehch'ak as 7ejkach’ or 7ejchak’ or 7ejk'ach, Ch'ol speakers may have been influenced by the patterns attested in the whole set of disyllabic forms, which disfavor /ch’/ in medial (only one Proto-Ch'olan case, ‘fingernail’) and final (only one Proto-Ch'olan case, ‘cornhusk’) positions, and disfavor /k’/ in final position (only two Proto-Ch'olan cases, ‘nephew, cousin’ and ‘pet’). In other words, what is left is to favor /k’/ in medial position (13 cases), for even though /k/ in medial position is strongly supported (17 cases), placing /k/ in medial position would be counterbalanced by the dispreference for /ch’/ in final position (one case). This gives the impression that it was the place feature that underwent metathesis.Footnote 13 As far as ‘with’ is concerned, Tables 6 and 7 suggest the following: given the choice between metathesizing Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok as 7ekoty’ or 7etyok’ or 7ek'oty, Ch'ol speakers may have been influenced by disfavoring final /ty’/ < */t’/ (one Proto-Ch'olan instance out of 45, ‘liver’), and disfavoring final /k’/ (two aforementioned Proto-Ch'olan instances out of 45). What is left is medial /k’/ (13 Proto-Ch'olan instances out of 60) and final /ty/ (8 Proto-Ch'olan instances out of 45), even though medial /k/ is strongly attested (17 Proto-Ch'olan instances out of 60); apparently, the dispreference for final /k’/ would outweigh the preference for medial /k/. Again, this would give the impression that it was the place feature that underwent metathesis. Referring back to Table 5, the 10 attested instances of CVk'VC disyllabic roots in Ch'ol (not counting ‘fingernail’ and ‘with’) constitute a model that, together with the attested patterns for both glottalic and non-glottalic obstruents in medial and final positions, may have promoted the structurally-motivated metathesis of ‘fingernail’ and ‘with’ in Ch'ol.

A reviewer of this article suggests that a potential problem with my approach lies in the fact that, as a grammatical morpheme, -ity'ok/-ik'oty would be of high frequency, and thus one would expect it to have preserved the original sequence -ity'ok. The facts, nevertheless, are clear on this matter: this morpheme is still seen, in variation with the conservative variant, but the innovative variant appears to be much more frequent (see Aulie and Aulie Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009: 123); and the one source that attests to this form prior to metathesis taking place already exhibits only its grammaticalized function and meaning (Hopkins et al. Reference Hopkins, Guzmán and Josserand2008: 89). This could suggest that the type frequency of this structure was sufficient to counteract the token frequency of the grammaticalized, relational noun ‘with’ in Ch'ol. Indeed, when we revisit the data from Table 5, this time considering ‘fingernail’ and ‘with’, there would now be 12 roots in contemporary Ch'ol that fit the general CVk'VC template, and three that fit the narrower CVk'Vt template, and while there were previously five possible glottalic obstruents in the medial position (i.e., /b’ tz’ ty’ ch’ k’/), now there remain only three (i.e., /b’ tz’ k’/). In other words, metathesis appears to reinforce a specific Ch'ol tendency for the medial ejective of CVC'VC roots to be /k’/ (the backmost ejective in the language, as far as place is concerned), and eliminates the rarer (front) cases (i.e., /ty’ ch’/).

One question that arises, then, is whether this is a generalized Mayan constraint — a preference for /k’/ as the medial consonant in CVC'VC roots. Here I attempt only a preliminary test of this idea. In addition to the cases already noted in Table 5, the following 34 items are the early (Proto-Mayan, Proto-Central Mayan) roots of CVCVC shape with at least one glottalic consonant in one of its positions. In 16 cases, we find an initial C’, in 10, we find a final C’, and in nine, we find a medial C’. The first nine examples in Table 8 are the ones of immediate relevance here — those with medial C’. The pattern is similar to that obtained in the Ch'olan data: /b’ tz’ k’ q’/ appear in medial position. Ch'olan lacks cases of *q and *q’ due to the Greater Tzeltalan *q(’) > *k(’) shift. Despite the small sample size, four cases of *q’ appear in medial position, compared to one for *k’, two for *b’, and two for *tz’. This is important to understand the Ch'olan tendency, though, because several of the cases of medial /k’/ in the Ch'olan data do in fact derive from earlier *q’. Thus, it would seem that in earlier stages of Mayan, it was *q’ (more than *k’) that may have been favored in medial position in CVC'VC roots; this suggests that the tendency is for a preference of the backmost oral glottalic consonant to take the medial position. What is also interesting, as it constitutes a difference with respect to the Ch'olan pattern, is that in the early-stage roots there are only two instances (#4 and #5) of two glottalic consonants within the root (when we consider the implosive *b’), whereas in the Proto-Ch'olan data there were nine.

Table 8: Cases of CVC'VC roots in early stages of Mayan.

Overall, the data regarding the distribution of glottalic and non-glottalic obstruents in disyllabic roots support a structural motivation for the cases of metathesis discussed here (Hock Reference Hock1985). And as is common of metathesis in other languages, including perceptual metathesis (Blevins and Garrett Reference Blevins and Garrett1998), the features involved (glottal stricture, place of articulation) are features that can spread; in this case, glottal stricture would seem to stay put, while places of articulation trade, well, places — though this might just be a superficial impression, given the discussion offered earlier.

Although the overall patterns seen in di- and trisyllabic roots and stems support Hume's (Reference Hume2004) attestation half of the indeterminacy/attestation model, a somewhat more comprehensive test of such model can be attempted by means of a small corpus of Ch'ol texts: specifically, a digitized version of Whittaker and Warkentin (Reference Whittaker and Warkentin1965), a collection of 19 texts with a total of approximately 12,989 words. The collection was previously digitized, converted to a Word document, and thoroughly checked for orthographic conversion errors. I then searched for the following sequences: /ch'V(j)k/, /ty'V(j)k/, /k'V(j)ch/, and /k'V(j)ty/. The results, sorted for initial versus medial contexts for the ejectives /ch’/, /ty’/ and /k’/ in these sequences are shown in Tables 9 and 10.

Table 9: Examples of /k'V(j)ch/ versus /ch'V(j)k/ sequences (texts).

Table 10: Examples of /k'V(j)ty/ versus /ty'V(j)k/ sequences (texts).

Table 9 serves as a comparison with ‘fingernail’. Curiously, the collection of texts did not attest to a single instance of ‘fingernail’. At first glance it would seem that /ch'Vk/ sequences are more common than /k'Vk/ sequences, but the raw frequency is not the important factor here: all instances of the sequence /ch'Vk/ are in root-initial position (with the verb ch’äk ‘to curse’, the noun ch'ok ‘youth’, the noun ch'ik(-il) ‘gnat’, and the noun ch’äk ‘flea’), none in medial position (after a vowel); in contrast, there were 12 cases of /k'Vch/ immediately after a vowel (with aw-älak’-äch ‘your very own animal’ consisting of aw-älak’ ‘your animal’ plus -äch ‘intensifier’; muk’-äch consisting of muk’ ‘habitual tense/aspect marker’ plus -äch ‘intensifier’; and yäx ak'ach ‘peacock’), and none in initial position.

The comparison for the pattern comparable to that of ‘with’ is provided in Table 10. This time, ‘with’ actually makes up the majority of attestations: 74 examples of the /k'oty/ sequence, all of them medial contexts (i.e., -ik'oty), are cases of ‘with’. In addition, 39 examples, all of them root-initial, are cases of inflections of the same root, k'oty ‘to arrive (there)’ (inflected in incompletive k'ot-el and completive k'ot-i statuses). And lastly, there are three cases of the root b'ik’ity ‘small’ (see #13 in Table 4). There are no cases of /t'Vk/ sequences in root-initial or “medial” contexts.

Similarly, a search of the sequences in question in Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009), a dictionary of Ch'ol that contains lexical entries and sample sentences, yielded the results in Tables 11 and 12; see Appendix 4 for detailed remarks on some of the relevant entries. I do not consider token frequency, but simply type frequency, according to context (i.e., root-initial vs. medial). I define type for the present purposes as equivalent to lexeme, and thus, I count different inflectional and derivational forms of the same root or stem as one type.

Table 11: Dictionary type (lexeme) frequency of /k'V(j)ch/ versus /ch'V(j)k/ sequences.

Table 12: Dictionary type frequency of /k'V(j)t/ versus /t'V(j)k/ sequences.

Table 11 was meant to find ‘fingernail’ and forms with the sequences /k'V(j)ch/ and /ch'V(j)k/ to check for the more common contexts, specifically whether sequences like CVk'Vch are more common than CVch'Vk. At first glance, it might seem that the sequence /ch'Vk/ is more common than the sequence /k'Vch/. Nevertheless, all four cases of a “medial” context of the sequence /ch'Vk/ are morphologically analyzable: they are examples of affective (sound symbolic, whether onomatopoeic or synesthetic) derivations based on monosyllabic roots of the shape /CVch’/ plus a suffix sequence -V1k-ña (the vowel shown as V1 harmonizes with the vowel of the preceding root), so that the sequence /ch'Vk/ in such cases cuts across a morpheme boundary (i.e., /CV1ch’-V1k-ña/). Consequently, not one case makes up an actual disyllabic root. In contrast, one of the three examples of the sequence /k'Vch/ in a “medial” context consists of an actual CVk'Vch root, the root 7ak'ach ‘turkey’; the others consist of the grammatical term muk’-äch, consisting of muk’ ‘habitual aspect marker’ and the intensifier -äch, a form cited above in connection with the corpus of texts, where it makes up 10 of the 12 tokens of /k'Vch/ sequences, as well as the root -ejk'ach ‘fingernail’.

Table 12 provides the type frequencies attested in the dictionary for /k'Vt/ and /t'Vk/ sequences in initial and medial contexts. The distribution is lopsided, with only two instances of the /t'Vk/ sequence, both of them in medial contexts: one consists of the root -ity'ok ‘with, and’ and is explicitly listed as a “variant” of -ik'oty (Aulie and Aulie Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009: 123); the other consists of the affective term b'uty’-uk-ña ‘overflowing’, consisting of the root b'uty’ ‘to fill (something) up’ and the affective derivation -V1k-ña, which means that the /ty'Vk/ sequence cuts across morpheme boundaries, just like Proto-Ch'olan *7et'ok did originally (recall proposed etymology as *7et=7ok based on *7et ‘partner’ and *7ok ‘foot/leg’). In contrast, there are not only more cases of “medial” /k'Vty/ sequences, but two of them include disyllabic roots: -ik'oty ‘with, and’, and b'ik’ity ‘small’. The remaining “medial” contexts involve cases where the sequence /k'Vt/ cuts across morpheme boundaries (pek’-7atyax, k'oty(a)-7atyax, 7ik’-7atyax, juk’-u=tyun).

Last, while the question of potential acoustic indeterminacy of the kind that would tend to “[force] the listener to rely on language experience to parse the signal” (Hume Reference Hume2004: 216) is not directly addressed here, I hypothesize, based on the corpus test carried out here, that the /CVch'Vk/ and /CVty'Vk/ sequences are likely to be rare in Ch'ol discourse, and that such rarity might result in a greater chance of acoustic misperception, which could motivate speakers to reshape them in terms of more frequent and lexically familiar sequences with a medial /k’/.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Although at first it seems that two cases of metathesis hardly merit mention and can be dismissed as irregular, sporadic changes, the result of the present exercise is rather interesting: these two examples of unusual metathesis, affecting the place feature of stops but seemingly ignoring their glottalic feature, conform to a broader, regular pattern of Ch'ol disyllabic /CVC'VC/ roots and stems favoring the back velar ejective /k’/ as the medial ejective, which may itself represent a more generalized Mayan pattern favoring /k’/ and /q’/ in such position, when one considers both *k’ and especially *q’ as sources of Ch'olan *k’.Footnote 14 Alternatively, they could be seen as the result of two patterns: a pattern favoring /k’/ as the medial ejective in disyllabic roots, and the dispreference for final /k’/ and final /ty’/ in disyllabic roots. Either way, these cases of metathesis abide by a structural motivation of the type supported by Hock (Reference Hock1985); they could also constitute a case of perceptual metathesis given that it affects glottalic consonants (specifically ejectives) (Blevins and Garrett Reference Blevins and Garrett1998). More specifically, these cases support the attestation part of the indeterminacy/attestation approach by Hume (Reference Hume2004). Since Mayan roots are predominantly monosyllabic, there likely is little room for increasing the dataset of disyllabic roots to further test this hypothesis.

Having said this, given the admittedly narrow scope of this article, the structural constraints proposed here for Ch'ol, and for Mayan languages more generally, should be tested by means of a more comprehensive analyses of other Mayan languages, including corpus and experimental approaches, the latter aimed at understanding native speaker intuitions of different types of disyllabic roots with glottalic consonants. Nevertheless, the present exercise offers a starting point.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Ch'olan Disyllabic Roots (n = 130): Alphabetic Listing

The following table provides the disyllabic roots reconstructed to Proto-Ch'olan by Kaufman and Norman (Reference Kaufman, Norman, Justeson and Campbell1984). I maintain the Spanish abbreviations for grammatical class (“gr”) used by those authors: aj = adjetivos (adjectives), adv = adverbio (adverb), instr = instrumental (instrumental), num = número/numeral (numeral/number), pt = partícula (particle), s = sustantivos (nouns), sr = sustantivo relacional (relational noun), sv = sustantivos verbales (verbal nouns), vi = verbo intransitivo (intransitive verb), vp = verbo posicional (positional verb), vt = verbo transitivo (transitive verb). I have incorporated a few corrections based on the more recent reconstructions by Kaufman with Justeson (Reference Kaufman and Justeson2003). The digraph <nh> stands for /ŋ/.

Appendix 2. Ch'olan Disyllabic Roots (n = 130): Sorted for Medial Consonant

Appendix 3. Ch'olan Disyllabic Roots (n = 130): Sorted for Final Consonant

Appendix 4. Notes relevant to Tables 11 and 12.

The following are remarks relevant to the items of relevance to Tables 11 and 12. I have introduced <b’> for Aulie and Aulie's, and <7> for their <’>, including root-initially, which Aulie and Aulie omit systematically. I have also added morpheme boundaries: <-> for affixes, <=> for terms of a compound. I have provided my own English translations from the Spanish entries in the dictionary.

With regard to Table 11, the following entries of relevance to the sequence /k'Vch/ were found in Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009): k'ach ‘to twist’, ak'ach ‘turkey’, -ejk'ach ‘fingernail’, ña[7]=[7]ak'ache ‘turkey hen’, yäxak'ach ‘wild turkey’, k’äch-choko-n ‘to set someone to ride on (something)’ ‘to mount someone onto something’, k’äch-l-ib’ ‘saddle (montura)’, k’äch-l-ib’-äl ‘horse, mule’ (something for mounting/riding), k’äch-ta-n ‘to mount, ride’, muk’äch (muk’ ‘habitual’, -äch ‘intensifier’), k'ochilan ‘to bend (the hand)’, k'och-ol ‘twisted’, k'ocholmetel ‘winding (road)’, k'uch ‘to arch (bend)’, k'uch-ul b'uch-ul ‘seated with head tilted down’, k'uch-uk-ña ‘related to the manner in which a person walks hunched over’ (k'uch-uk-ña), k'uchu pat ‘hunchback’ (e.g., k'uch-u(l)=pat).

Also with regard to Table 11, the following entries beginning with /ch'Vk/ appear in Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009): ch'ak ‘bed’, ch'akute7 ‘tapesco (bed) for drying up beans and coffee’ (almost certainly based on ch'ak ‘bed’), käch’-äk-ña ‘the sound made by a new rope when it is moved’, ch’äk ‘to curse’ (transitive), ch’äk ‘flea’, ch’äkojel ‘to curse’ (intransitivized form), ch’äk-oñ-el ‘witchcraft’, ch’äktal ‘hill or edge of a hill that serves as a lookout’, kech’-ek-ña ‘grinding/grating (teeth)’, ch'ik-ijl ‘chaquiste (biting midge)’, ch'ik ‘to insert (small instrument in a hole)’, mich’-ik-ña ‘angry’, tich’-ik-ña ‘with extended hand/arm’. Nicholas Hopkins (personal communication, 2020) suggests that ch'ik-ijl is likely based in ch'ik ‘to insert’, as these insects “take a bite out of your flesh and leave a little hole,” though he is unsure what the -ijl component might be.

With regard to Table 12, the following entries beginning with /k'Vty/ appear in Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009): k'ajtye7 ~ k'atye7 ‘bridge’, k'ajtye7ja7 ‘paso de agua (place)’, k'ajti-b'e-n ‘to ask (someone) (a question); to ask (someone) (for something)’ (tv), k'ajti-bil ‘engaged (for marriage); asked; ordered/reserved’, k'ajti-n ‘to ask (a question); to ask (for something)’ (tv), k'ajti-sa-n ‘to come to an agreement; to agree’, k'atinb’ak ‘domain of demons and destiny of bad people’, 7ik'atyax ‘early morning, dawn; at or before dawn’ (7ik’-7atyax, -7atyax ‘suffix for emphasizing; intensifier’), pek’-7atyax ‘it is low’ (see pek’ ‘short (in height); low; humiliated’), xtujk'atye7 wakax ‘bull’, k’äty ‘crossed’ (atravesado), k’äty-äl ‘crossed’, -k’ätylontye7el ‘lintel; crossbeam where the post is tied’, b'ik’ity ‘small’, *b'ik’itye7lel ‘roof rods’, k'otyel ‘to arrive (there)’, k'oti ‘arrived (there) (completive)’, k'otiyon ‘I arrived’, k'otib’ ‘destiny’, k'otyem ‘arrived (there) (participle)’, k'otya ‘pretty’, k'oti ‘dry’, yik'oty ‘with, and’, a wik'oty ‘with you’, kik'oty ‘with me’, xijk'otye7an ‘to shore up (house)’ (xij=k'otye7-an?), la kik'oty ‘with us’, k'ojty ‘shoot (of plant)’, k'uty ‘to grind (chilli pepper)’, k'uty-ilan ‘to grind (chilli pepper)’ (-ilan ‘indicates movement’), juk'utyun ‘piñanona (vine)’ (“swiss cheese plant”, Monstera deliciosa). Nick Hopkins (personal communication, 2020) analyzes juk'utyun as juk’-ul=tyun ‘shaved stone/egg’, consisting of the verb root juk’ ‘to shave’ in its stative form, juk’-ul ‘shaved’, and the noun tyun ‘stone/egg’, referring to the process for curing the fruit by shaving the scales and flesh off, leaving only the edible core.

Also, with regard to Table 12, the following entries beginning with /ty'Vk/ appear in Aulie and Aulie (Reference Aulie and de Aulie2009): y-ity'ok ‘with, and’, listed as a “variant” of y-ik'oty, and b'uty’-uk-ña ‘overflowing; full’.