Introduction

Perinatal mental health disorders (PMHD; i.e., anxiety, nonpsychotic depressive episode, manic or psychotic episodes, post-traumatic stress disorder, and adjustment disorder occurring during pregnancy and the first year after childbirth) affect up to one in five women in high-income countries and are often associated with poor parental and child outcomes [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1]. PMHD are in particular frequent in women with serious mental illness (SMI) (i.e., schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression) and autistic women [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1, Reference Dubreucq and Dubreucq2]. Despite an estimate cost of £8.1 billion per year in the United Kingdom (UK), PMHD remain predominantly unrecognized, undiagnosed, and untreated [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1].

Guidelines and action plans from the WHO and many countries support prevention, early detection of PMHD, and improved access to specialist perinatal mental health services (SPMHS) [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1]. Despite efforts to address gaps in perinatal mental health care (PMHC) in some countries (e.g., £365 million invested between 2016 and 2021 in England) the access to these services remain often heterogeneous (e.g., ¼ of the women in the UK had no access to SPMHS in 2018 [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3]). In France, suicide is the leading cause of maternal mortality during the first year of life, responsible of approximately one death per month between 2013 and 2015 [4]. Of these deaths, 91% could be considered as avoidable because of nonoptimal care (i.e., lack of detection, referral, or treatment). Aligning with this, only 27.4% of the pregnant women reporting psychological distress in the French ELFE study had access to SPMHS [Reference Bales, Pambrun, Melchior, Glangeaud-Freudenthal, Charles and Verdoux5] and large areas of France remain without access to outpatient SPMHS or mother-baby units.

In a recent systematic review, Webb et al. [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3] identified barriers and facilitators to the implementation of SPMHC, influential at different levels across the care pathway. While a number of qualitative studies described the barriers to accessing SPMHS or to the implementation of SPMHC, there remain some limitations to the current body of evidence. First, most studies were conducted in the United States or the UK and did not compared the perspective of different stakeholders (e.g., solely mothers with PMHD or health providers [HPs]; mixed samples between mothers and obstetric providers [OPs]; [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3, Reference Sambrook Smith, Lawrence, Sadler and Easter6]). Second, while optimal service provision refers to person-centered care coproduced with persons with lived experience (PLEs; [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3]), most studies did not involve researchers with lived experience nor used a participatory design. Third, research on personal recovery in PMHD remains scarce [Reference Forde, Peters and Wittkowski7, Reference Law, Ormel, Babinski, Plett, Dionne and Schwartz8]. Fourth, while men often experience depression during the peripartum (8–10% of the fathers; [Reference Rao, Zhu, Zong, Zhang, Hall and Ungvari9]), their place in the PMHC is mainly envisioned from the perspective of their partner, for example (lack of) partner support [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3, Reference Sambrook Smith, Lawrence, Sadler and Easter6]. Fifth, most studies excluded women with SMI or autistic mothers and did not cover preconception care [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1, Reference Dubreucq and Dubreucq2].

To improve PMHC in France, the first 1000 days national commission issued recommendations that will be completed by guidelines from the National Health Authority. To guide the design of an innovative optimal service provision, this qualitative participatory study explored the experiences, views, ideas, and expectations of (i) PLEs of PMHD, SMI, or autism, (ii) OPs, (iii) childcare health providers (CHPs), and (iv) mental health providers (MHPs) on how to improve PMHC and in particular the care of perinatal depression. France is a relevant setting to examine this question because of its long-established interest in perinatal mental health (PMH) and perinatal psychiatry [Reference Brockington, Butterworth and Glangeaud-Freudenthal10]. We conducted nine focus groups and 24 individual interviews for a total number of 84 participants (24 PLEs, 30 OPs, 11 CHPs, and 19 MHPs).

Methods

Evidence before this study

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, and Embase for articles published in English and in French between January 1, 2000, and May 22, 2023, using the search terms “improvement,” “perinatal (peripartum, antenatal, postnatal),” “mental health care,” “participatory (collaborative, coproduction),” and “recovery” (recovery-oriented, person-centered, treatment preferences). We screened the reference list of five systematic reviews on topics related to the improvement of PMHC. The search yielded 75 articles applicable to our study objective (Supplementary Table 1).

Study design and participants

The present study used a qualitative participatory research design, combining focus groups (for providers) and in-depth individual interviews (for PLEs) conducted between December 2020 and May 2022. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ; [Reference Tong, Sainsbury and Craig11]) were used to design the study protocol and report results. HPs were recruited through three perinatal health networks in Auvergne Rhône-Alpes (ELENA for Saint-Étienne, AURORE for Lyon and Auvergne Perinatal Health Network (RSPA) for Clermont-Ferrand) and a group of experts in PMH in Ile de France. An advert was distributed through the social media of Maman Blues, an association of persons with maternal distress, to recruit PLE of PMHD. Women with SMI and autistic women were recruited through a center for psychiatric rehabilitation from the REHABase network (Grenoble). Eligible participants in the PLEs group were adults (age > 18) with lived experience of PMHD (self-identified) and adults with a confirmed diagnosis of SMI (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or major depression; DSM-5; [12]) or autism spectrum disorder (DSM-5, [12]), who had a lived experience of PMHD or had contact with perinatal health services (i.e., through prior pregnancies or preconception care). Eligible participants in the HPs’ group were OPs (midwives and obstetricians), CHPs (pediatricians, general practitioners, pediatric nurses, childcare assistants), and MHPs (child and adolescents (C&A) psychiatrists, adult psychiatrists, psychologists, mental health nurses, social workers). The relevant Ethical Review Board (CPP-Ile de France I) approved the appraisal protocol on March 10, 2020, and all participants gave informed consent.

Procedure

Researchers’ own position, views, and opinions can influence the research process [Reference Finlay13]. We thus used a participatory research design (i.e., coproduction by academic researchers and a coresearcher with lived experience as equal partners; [Reference Egid, Roura, Aktar, Amegee Quach, Chumo and Dias14]) and adopted a reflexive position from the inception of the project to ensure that researchers’ feminist convictions did not dominate the study design or data collection and analysis. Nine focus groups and 24 individual interviews were conducted for a total number of 84 participants. To capture the complexity of the topic and to facilitate participants’ expression on sensitive information (i.e., their personal experiences, views, feelings, and attitudes; [Reference Kruger, Rodgers, Long and Lowy15]), we conducted in-depth individual interviews for PLEs and separate focus groups for HPs according to their type of practice (i.e., OPs; CHPs; MHPs). Given the pandemic context, most individual interviews and focus groups were conducted online using secured video-conferencing solutions.

Focus groups are group discussions where the moderator uses a semi-structured group interview to address specific issues and to ensure that the discussion remains on the subject of interest. Apart from this artificial structure, efforts were made to create a group environment as close as possible to a naturally occurring social interaction. Participants were asked the same set of questions in the individual interviews and in focus groups (semi-structured interview in Supplementary Table 2). Participants were asked to discuss their personal experiences, views, feelings, and attitudes toward PMHC and in particular toward the care of perinatal depression (PPD) (e.g., the challenges they faced or anticipated and the resources they identified). They were encouraged to formulate their ideas on how to improve PMHC. We purposely put a focus on PPD for this study because this condition gained awareness in the general public and in HPs over the recent years (e.g., specific citation in the national “first 1000 days of life” commission report). General information was recorded for PLEs (age, gender, education, marital status, number of children, psychiatric diagnosis) and HPs (age, gender, profession, type of practice, for example, hospital or private practice, duration of professional experience and confidence when caring for patients with PPD). After participants consented to participate and agreed to the recording of the session, discussions lasted around 2 hours. Individual interviews and focus groups were conducted by at least two members of the research team, video and tape recorded and fully transcribed. In order to ensure the participation of all participants, the second moderator regularly invited those who did not spontaneously contribute to share their experience, thoughts and feelings about the topics covered. The first author checked the final transcription against the recordings.

Data analysis

For the thematic analysis, we used an inductive, rather than theoretical, approach to qualitatively analyze the data (i.e., “bottom-up” identification of themes). More specifically, we followed the six-step process by Braun and Clarke [Reference Braun and Clarke16]: researchers familiarized themselves with the data as a whole, generated initial codes, searched for themes, reviewed themes, named each defined theme, and produced the final report. Themes were refined by reexamining the coherence of data codes within each theme and the validity of each theme in relation with the whole dataset. Coder debriefings occurred throughout the analysis to review the identified themes and reach an agreement on coding discrepancies. To allow a deeper and broader understanding of the topic and reduce the risk of interpretation biases, we used methodological triangulation (i.e., individual interviews and focus groups), investigator triangulation (i.e., independent coding by two researchers with different backgrounds, a specialist midwife and a perinatal psychiatrist and review of all codes by a second perinatal psychiatrist and a coresearcher with lived experience of PMHD) and data triangulation (i.e., comparison of the perspective of various stakeholders – PLE and diverse HPs – on a same topic). Participants did not give their feedback on the results. We obtained code saturation and meaning saturation at the end of the study, that is, the point in the research process where no new information is discovered in data analysis and when no further dimensions, nuances, insights of issues can be found [Reference Hennink, Kaiser and Weber17]. Given the inclusion of nonparents in the PLEs group could have influenced the interpretation of the results, we conducted an additional analysis after removing these participants to search for potential differences in the identified themes.

Results

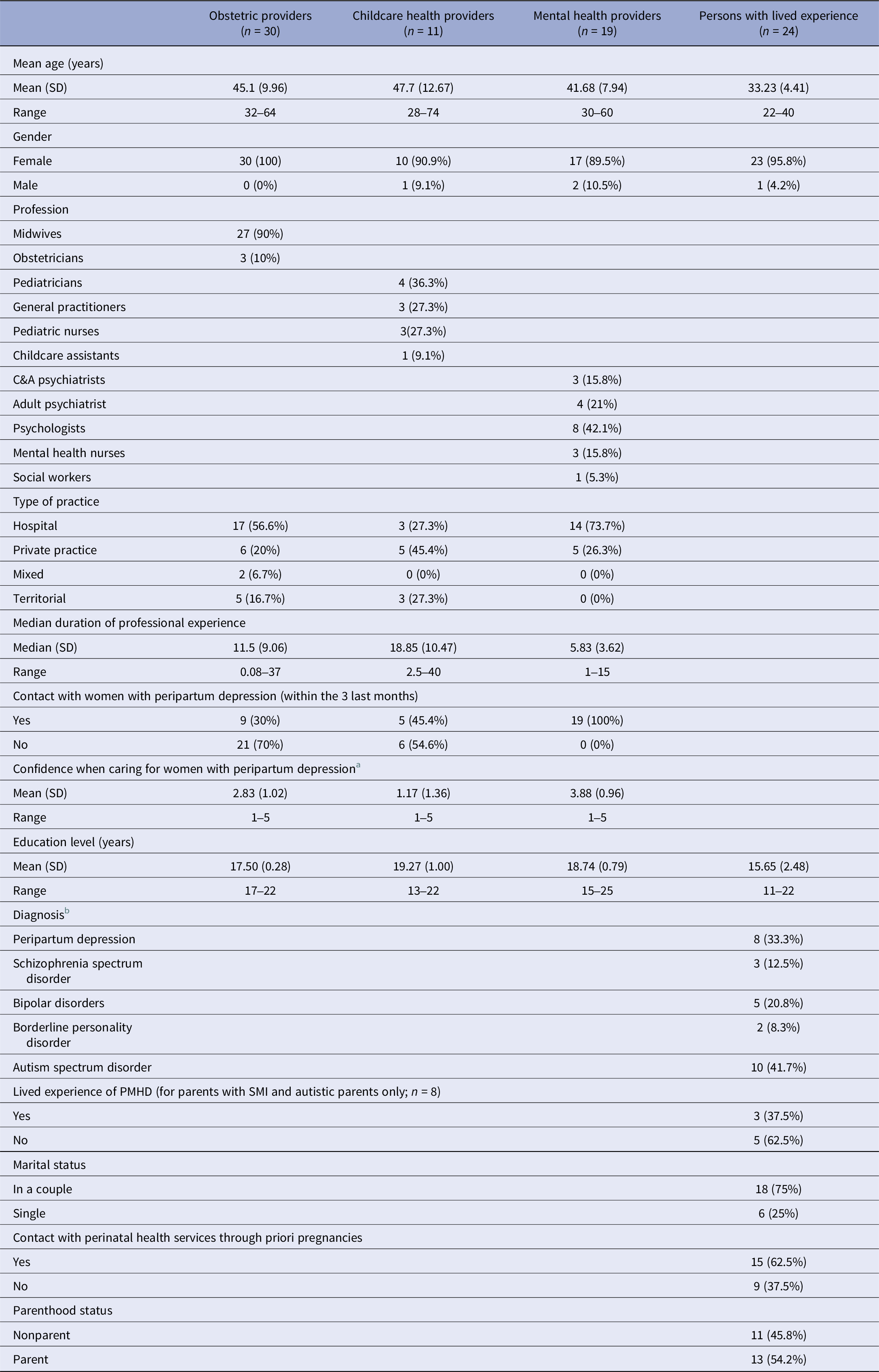

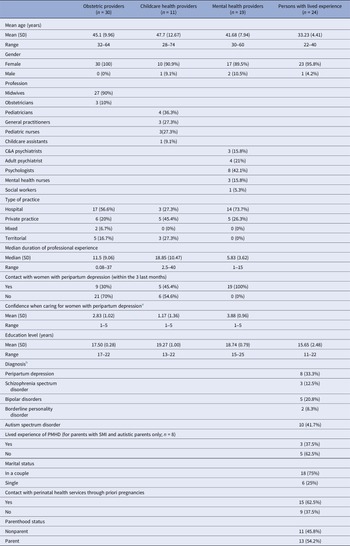

Nine focus groups and 24 individual interviews were conducted (n = 84 participants). The PLE group was composed of 4 women and 1 man with lived experience of PMHD, 9 women with SMI, and 10 autistic women. Of the PLE group, 62.5% had contact with perinatal health services through prior pregnancies (54.2% had children of any age). In the SMI and autism subgroups, three mothers also reported a lived experience of PMHD (37.5%). The provider group was composed of 30 OPs (27 midwives, 3 obstetricians), 11 CHPs (4 pediatricians, 3 general practitioners, 3 pediatric nurses, 1 childcare assistant), and 19 MHPs (3 C&A psychiatrists, 4 adult psychiatrists, 8 psychologists, 3 MH nurses and 1 social worker). Sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample characteristics

a From 1 (Not comfortable at all) to 5 (very comfortable).

b Four participants had two cooccurring conditions (one woman with bipolar disorder and borderline personality disorder; three autistic mothers with peripartum depression).

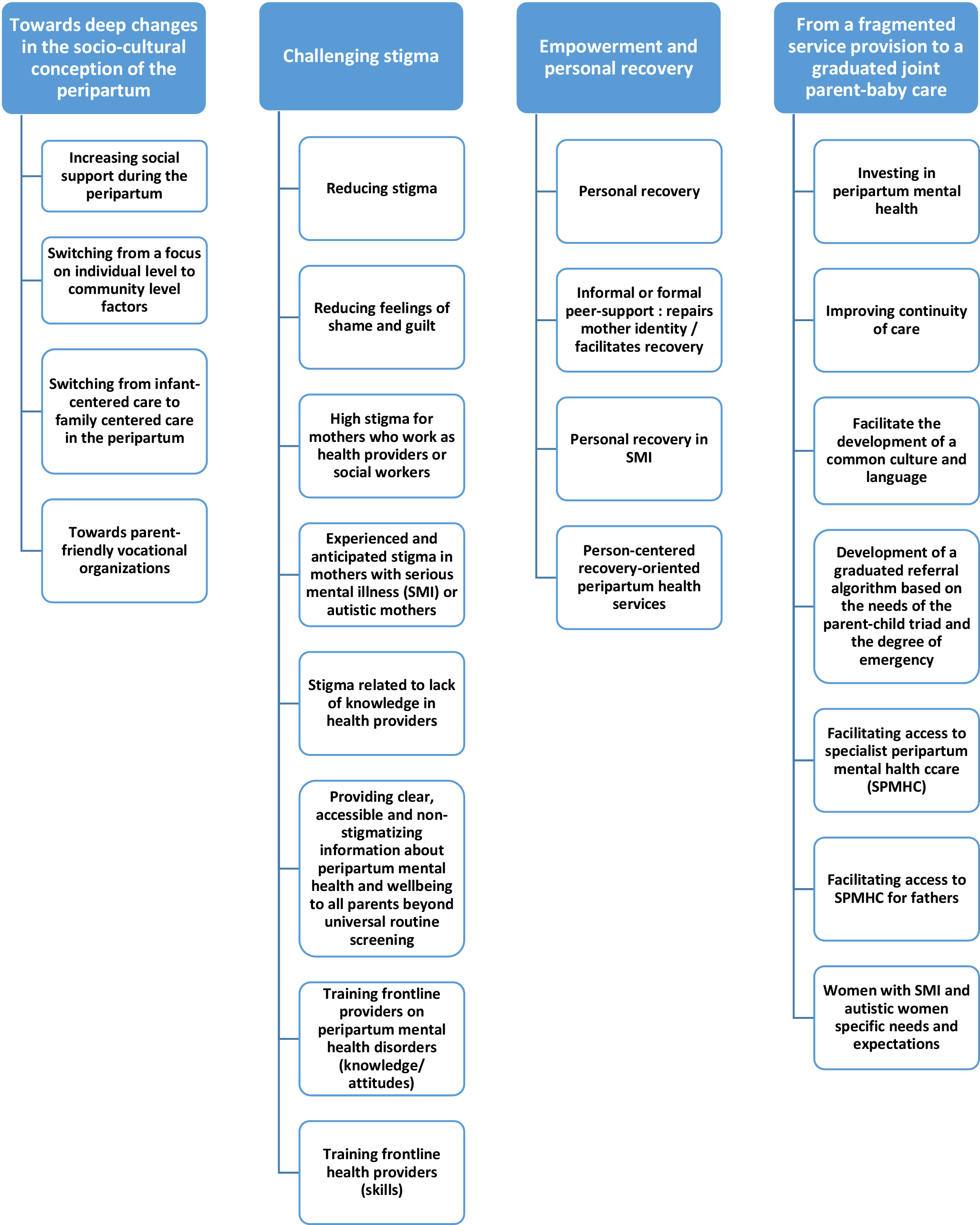

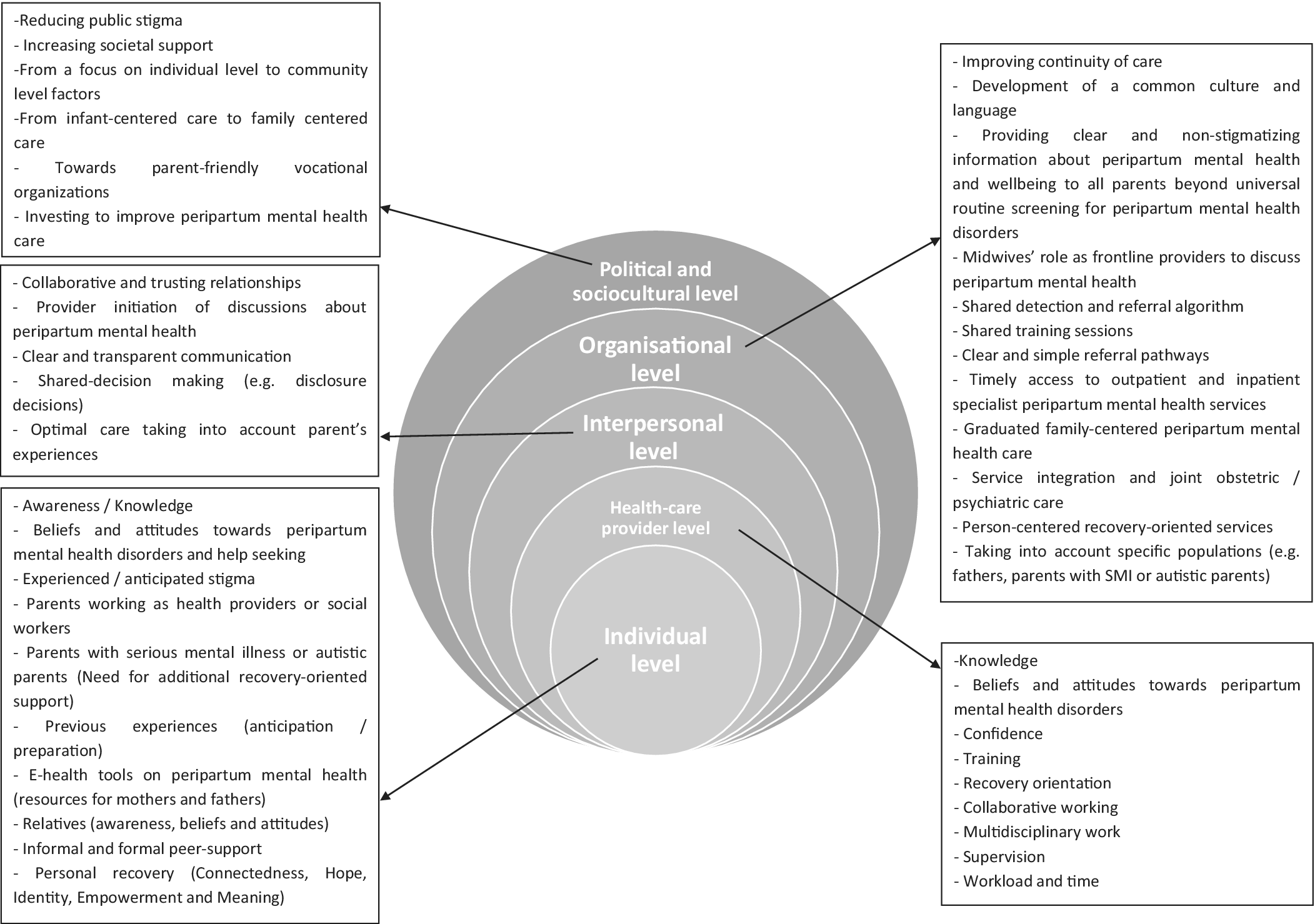

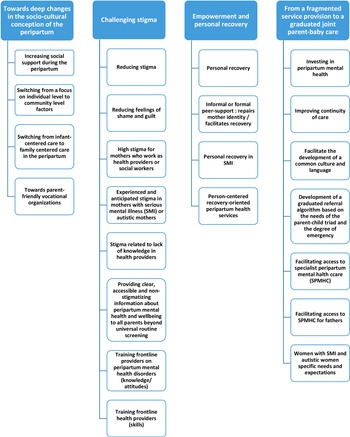

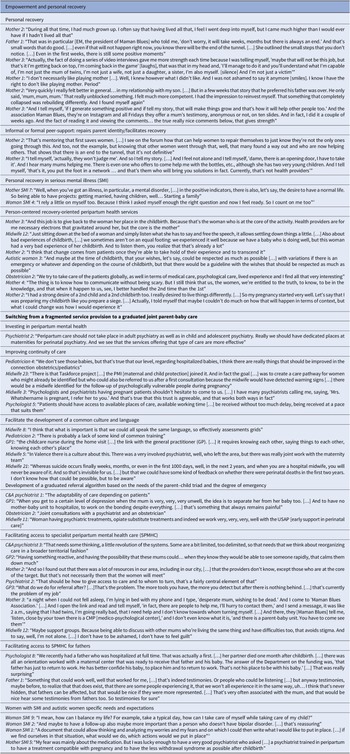

The thematic analysis generated four super ordinate themes: (i) toward deep changes in the socio-cultural conception of the peripartum; (ii) challenging stigma; (iii) empowerment and personal recovery; and (iv) from a fragmented service provision to a graduated joint parent-baby care. We found no differences in the identified themes after removing nonparents in the PLEs group from the analyses except for subthemes related to preconception care (identified by an asterisk in Table 3 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). The results of the qualitative analysis are presented in Figures 1 and 2, Tables 2 and 3, and Supplementary Tables 3–6 (quotations supporting the themes and subthemes). The list of abbreviations is presented in Supplementary Table 7.

Figure 1. Thematic tree.

Figure 2. System-level representation of results.

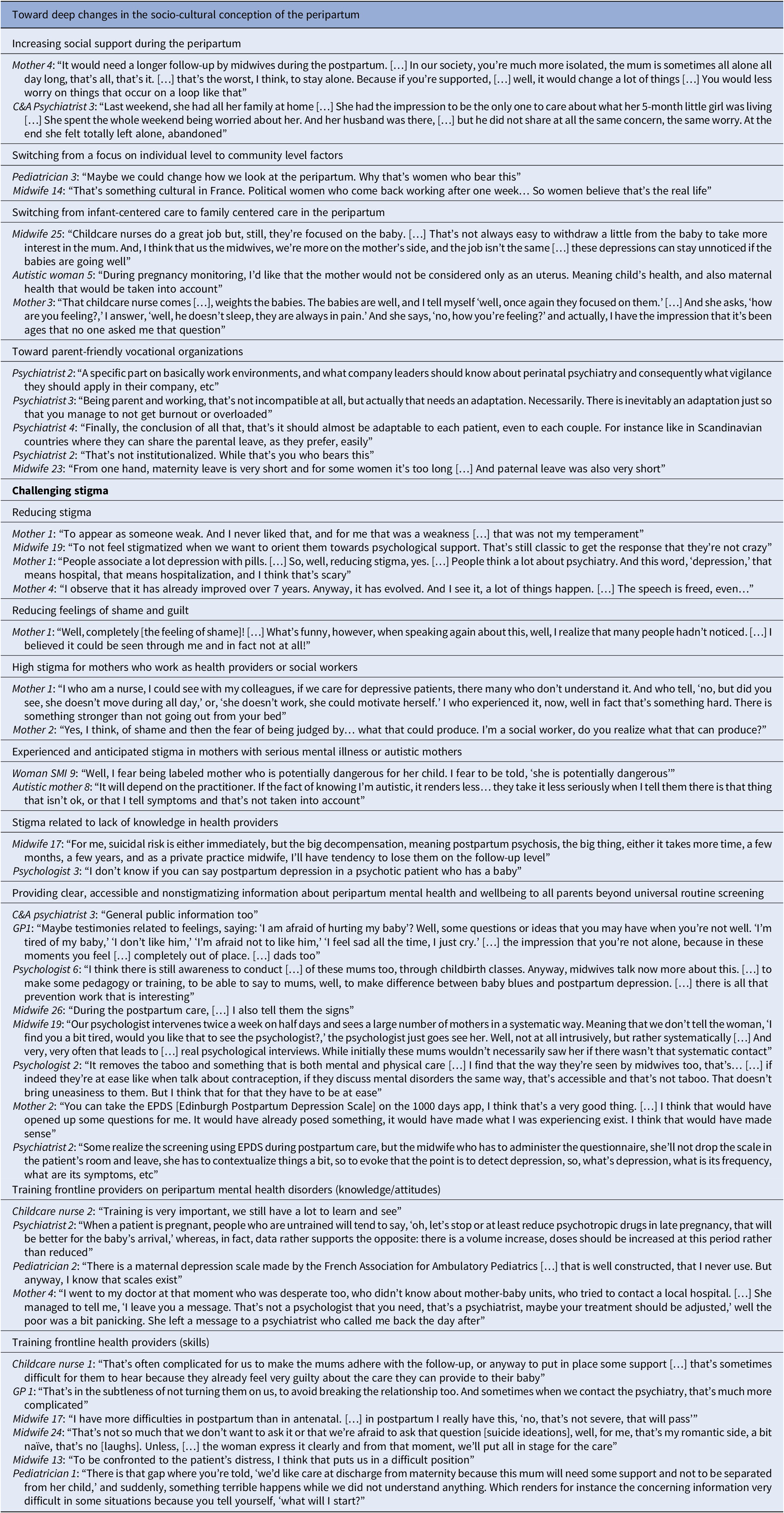

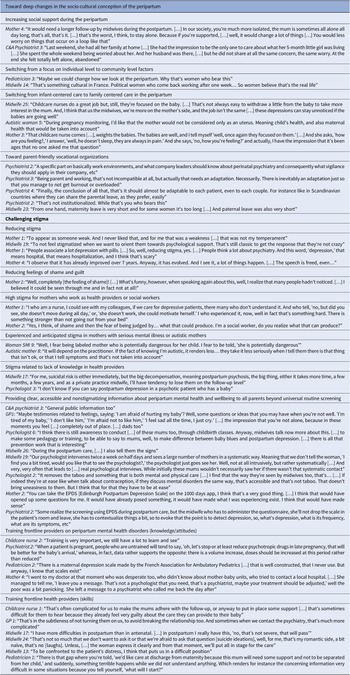

Table 2. Quotation supporting the themes “Toward deep changes in the socio-cultural conception of the peripartum” and “challenging stigma”

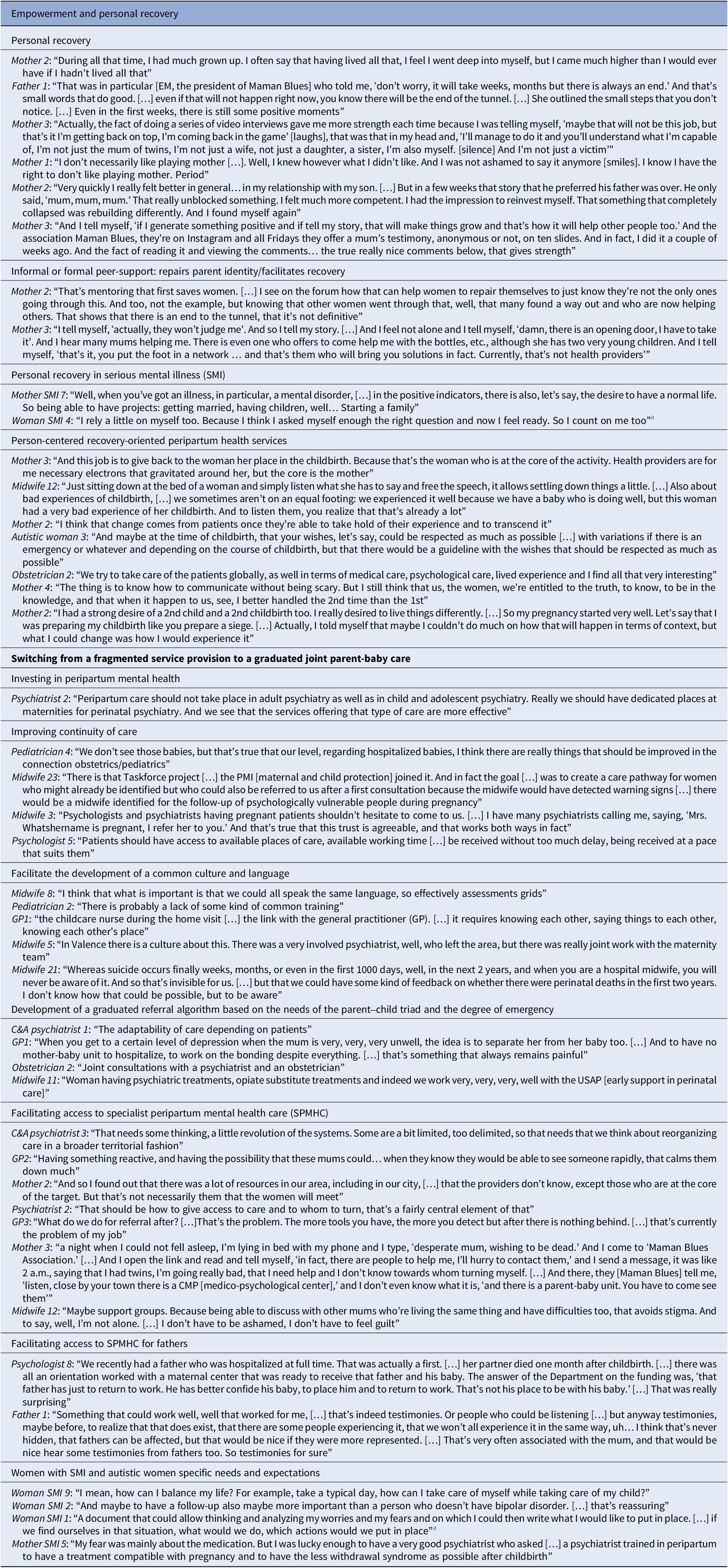

Table 3. Quotation supporting the themes “Empowerment and personal recovery” and “From a fragmented service provision to a graduated joint parent-baby care”

a Theme identified only by nonparents.

Toward deep changes in the socio-cultural conception of the peripartum

Changing socio-cultural conceptions of the peripartum to improve PMH was a theme running through all interviews or focus groups. Peripartum was described as a major life event with community-level implications (e.g., impact on the mother’s sense of personal identity, lifestyle, and social roles but also on the partner, the relatives and more broadly work environments). However, many participants felt that the community considered the peripartum mainly as a personal experience. While they acknowledged positive evolutions over the recent years, participants called for what they called a “cultural revolution” to improve PMH, that is, switching from a focus on individual level to community-level factors (e.g., switching from infant-centered care to family-centered care and adapting work environments to the needs of young parents).

Challenging stigma

Challenging stigma was another theme running through all interviews or focus groups. Public stigma (e.g., depression as weakness of character and inability to provide adequate childcare), feelings of shame about seeking help and anticipated stigma from relatives and HPs (e.g., fear of not being taken seriously) were major barriers to detection and timely access to PMHC. Mothers working as HPs or social workers anticipated additional stigma related to the intersection of PMHD and their vocational status. Women with SMI and autistic women reported experienced stigma from HPs during maternity care and anticipated to be discriminated against in case of disclosure. Additional barriers were described for fathers with PMHD (e.g., feelings of shame and limited access to perinatal support services such as “maternal centers”). Suicide ideations or SMI were associated with stigmatizing beliefs in HPs, for example, perceived dangerousness for others. OPs reported to fear of being intrusive when opening discussions about PMH with parents without identified risk factors.

Challenging stigma meant to improve knowledge, beliefs, and attitudes toward PMHD and SMI in the general public and in HPs. PLEs and HPs recommended providing clear, accessible, and nonstigmatizing information about PMH and wellbeing to all parents during the perinatal period. Similarly, universal routine screening was seen as a way to reduce stigma and to facilitate provider initiation of discussions about PMH with all parents. Participants outlined the need for an adequate training of HPs on PMH and wellbeing – and not merely on PMHD.

Empowerment and personal recovery

Parents with PMHD described personal recovery as a nonlinear self-broadening process aimed at living a meaningful life, a definition that corresponds to the CHIME framework proposed in SMI (connectedness, hope and optimism, identity, meaning, and empowerment; [Reference Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams and Slade18]). While HPs did not mention personal recovery or recovery-oriented practices, some OPs acknowledged the need for a shift from a medical conception of perinatal healthcare to a consumer-informed biopsychosocial perspective that considers the expertise of mothers. This included shared decision-making, for example, about disclosure of sensitive information to other HPs. Informal and formal peer support by PLEs played a central role in personal recovery for all participants. In addition to common themes identified by both parents and nonparents (e.g., being parent is a motivating factor for personal recovery), nonparents with SMI considered personal recovery as a facilitator in the decision-making process about starting a family.

From a fragmented service provision to a graduated joint parent-baby care

To improve the organization of perinatal healthcare, HPs formulated several recommendations influential at different levels across the care pathway: society, organizational, interpersonal, provider, and individual. Society-level factors included investments to improve access to SPMHS providing optimal family-centered care (e.g., perinatal psychiatric services, distinct from adult and child and adolescent psychiatry that offer graduated joint parent-baby care).

Organizational factors included improving the continuity of care and developing a common culture and language between non-MHPs and MHPs. Participants – in particular midwives – formulated the following ideas: (i) shared training sessions on PMH; (ii) regular supervision and feedbacks from MHPs to non-MHPs on clinical situations; (iii) e-health tools for a clear, secured, reactive, and transparent exchange of information between HPs and for an up-to-date directory of the local resources; (iv) universal routine screening and the implementation of a shared detection and referral algorithm graduated according to the parents-baby triad’s needs and the degree of emergency; (v) clear referral pathways; and (vi) access to reactive outpatient and inpatient SPMHS. In addition to mother-baby units, integrated inpatient or outpatient perinatal health services with OPs and MHPs were described as a useful resource for optimal SPMHC.

Provider-level and interpersonal factors included training non-MHPs and nonspecialized MHP on PMH to improve their sense of confidence when caring for parents with PMHD. Other factors included clear and transparent communication between parents and HPs and between non-MHPs and MHPs. Among parent-level factors, informal peer support facilitated the access to PMHC. Other factors included raising awareness on PMHD in parents and relatives, support groups, e-health tools on PMH and additional support for mothers with SMI and autistic mothers, for example, attending to a dual set of needs or optimal service provision including preconception care.

Discussion

Improving PMHC is a complex intervention that requires integrating the perspective of PLE, OPs, CHPs, and mental health providers [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3]. To our knowledge, this qualitative study is one of the first including all these populations using a participatory research design.

Inter-personal level and individual level factors

We found many interactions but also some degree of difference in the identified priorities between PLE (e.g., personal recovery and person-centered care) and HPs (e.g., common culture, improving inter-provider communication and risk management). This aligns with the emerging literature on personal recovery in PMHD that focused on the perspective of mothers [Reference Forde, Peters and Wittkowski7, Reference Law, Ormel, Babinski, Plett, Dionne and Schwartz8, Reference Powell, Bedi, Nath, Potts, Trevillion and Howard19]. Competing priorities between PLEs and HPs are also observed in the literature about recovery in SMI [Reference Le Boutillier, Slade, Lawrence, Bird, Chandler and Farkas20] and concerned in particular women with SMI, for example, anticipated challenges during the peripartum in PLEs versus risk management in HPs. This aligns with recent qualitative research comparing the experience of (future) parents with SMI and MHPs [Reference Dubreucq, Lysaker and Dubreucq21].

PLEs and some OPs acknowledged the need for a shift from a medical conception of perinatal healthcare to a person-centered perspective considering the expertise of parents. Beyond improving parental PMH [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3, Reference Verbiest, Tully, Simpson and Stuebe22], horizontal and collaborative relationships, self-determination, empowerment, social connectedness, and peer support facilitated personal recovery in parents with PMHD. Howard et al. [Reference Howard, Trevillion, Potts, Heslin, Pickles and Byford23] showed improved mothers’ satisfaction after admission to a mother-baby unit compared with generic inpatient care, a finding that could be related to the provision of noncoercive specialist care. This suggests that recovery-oriented practices (i.e., strength-based person-centered approach supporting hope, empowerment, and goal-striving; [Reference Slade, Bird, Clarke, Le Boutillier, McCrone and Macpherson24]) could be relevant in perinatal health services and SPMHS.

While public stigma and anticipated stigma had negative effects on PMH, help–seeking, and engagement into the care pathway for all parents [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3, Reference Dubreucq, Plasse and Franck25], we found that this was particularly the case of four populations, that is, men with PMHD, non-MHPs or social workers with PMHD, women with SMI and autistic women (e.g., fear of being labeled as “dangerous,” “fragile,” or “bad mothers”; [Reference Dubreucq and Dubreucq2, Reference Dubreucq, Lysaker and Dubreucq21]). This concurs with research on fathers with PMHD [Reference Lever Taylor, Billings, Morant and Johnson26] and HPs with nonperinatal depression [Reference Davis, Cher, Friese and Bynum27].

Healthcare provider level factors

Aligning with Noonan et al. [Reference Noonan, Jomeen, Galvin and Doody28], stigma in HPs included the fear of being intrusive when discussing PMH with women without identified risk factors and the desire to protect them from “being labeled” by a referral to SPMHS. While non-MHPs reported more negative attitudes in case of suicide ideations or history of SMI, this aligning with previous research [Reference Lau, McCauley, Barnfield, Moss and Cross29], several HPs expressed concerns about disclosing sensitive information with other HPs, this leading them to support shared decision-making (SDM) in this context. This concurs with the positive effects of SDM in treatment options on women’ experiences of PMHC [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3] and decisions about disclosure in SMI [Reference Dubreucq, Plasse and Franck25]. Training sessions should target the interaction between knowledge and beliefs and attitudes (i.e., stigma [Reference Dubreucq, Plasse and Franck25]) and include content about interviewing skills, distress management, parents with SMI and autistic parents [Reference Howard and Khalifeh1, Reference Dubreucq and Dubreucq2].

Political and socio-cultural level factors

Extending the results of previous research that focused on organizational, interpersonal, HP, or individual levels [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3], we found that society-level factors, for example, switching from infant-centered care to family-centered care and promoting parent-friendly vocational organizations, are determinant to improve PMHC. This aligns with the benefits of paternity leave uptake on paternal PMH [Reference Barry, Gomajee, Benarous, Dufourg, Courtin and Melchior30] and Wilkinson [Reference Wilkinson31] proposition of a research agenda to examine the interaction of maternal PMH and employment. Consistently with other high-income countries (e.g., the UK; [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3]), participants called for an adequately funded national public policy to address the gaps in PMHC (e.g., access to reactive perinatal psychiatric services [Reference Brockington, Butterworth and Glangeaud-Freudenthal10]).

Organization-level factors

Participants identified factors influential at the organizational level (e.g., clear referral pathways) that concur with Webb et al. [Reference Webb, Uddin, Ford, Easter, Shakespeare and Roberts3]. Participants called for a universal promotion of PMH for all parents extending beyond universal screening, this aligning with studies reporting that parental PMH should be integrated into standard perinatal health care [Reference Verbiest, Tully, Simpson and Stuebe22, Reference Laios, Rio and Judd32]. Other recommendations included offering more resources for fathers with PMH and additional recovery-oriented care to mothers with SMI or autistic mothers, this aligning with recent qualitative research [Reference Dubreucq, Lysaker and Dubreucq21, Reference Lever Taylor, Billings, Morant and Johnson26]. Patient representative associations were determinant at different levels across the care pathway (e.g., raising awareness; facilitating access and referral to SPMHC; facilitating personal recovery).

Limitations

There are limitations. First, our sample was self-selecting (i.e., persons interested in improving PMHC) and cannot be considered as representative of the experience of all stakeholders involved in PMHC. However, the large size (n = 84), the diversity of the sample (i.e., realization in five distinct locations, the inclusion of various PLEs [including women with SMI and autistic women], and inclusion of HPs with diverse backgrounds and practices working in urban, semi-urban and rural areas) and the use of three triangulation methods (i.e., investigator, methodological and data triangulation) are considerable strengths. Similarly, the proportion of women was high in all groups (95% in the HP group and 95.8% in the PLEs group) and most HPs worked in public hospitals (56.7%), thereby reducing the generalizability of our findings to men and private practice providers. Of 24 PLE of PMHD or SMI, ¼ worked as HPs or social workers. Given the experience of this at-risk population remains under-investigated, this could be a strength. Second, given nonparents may have limited lived experience of perinatal healthcare apart from preconception care, the high proportion of nonparents (45.8%) included in the PLEs group could be a limitation. However, we found no difference in the identified themes after removing these participants from the qualitative analysis – except for subthemes related to preconception care (e.g., personal recovery as a facilitator in decision-making about starting a family and joint crisis plans). Third, many individual interviews or focus groups were conducted online because of the pandemic context, which could have affected the quality of data collection. However, in-person and online focus groups yielded comparable themes and online discussions facilitated sharing of in-depth personal stories and discussion of sensitive topics in a recent study [Reference Woodyatt, Finneran and Stephenson33]. Fourth, researchers’ own position, views, and opinions can influence the research process [Reference Finlay13]. Adopting a participatory research design and a reflexive position from the inception of the project may have addressed this limitation. Fifth, we did not involve managers from public hospitals or local/regional public healthcare agencies or politicians in this study, which is a limitation given the role of these stakeholders in decision-making about healthcare.

Overall, this analysis generated novel insights into how to improve PMHC for all users including those with SMI or autism. These include a community focus on PMH, family-centered care, a better integration of mental health and perinatal health care and recovery-oriented practices.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2023.2464.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to women, men, and health providers who participated in this research and who shared their times, experiences, and ideas. We thank the FondaMental Foundation (www.fondationfondamental.org), which is a nonprofit foundation supporting research in psychiatry in France. We would like to thank Mrs Aurélie Delmas (perinatal health network ELENA), Mrs Mathilde Dublineau (Naître et Bien-Être network), and Mr Laurent Gaucher (midwife and researcher) who participated in the early stages of the study and data collection. We would like to thank Pr Céline Chauleur, Dr Tiphaine Barjat, Dr Laure-Élie Digonnet, Pr Cyril Huissoud, Pr Pascal Gaucherand, Pr Denis Gallot, Dr Amélie Delebaere (obstetricians), Mrs Stephanie Weiss (midwife), and Dr Catherine Salinier (French association of outpatient pediatrics) for their support to this project. We are also grateful to the reviewers of a previous version of the manuscript for their helpful comments.

Author contribution

J.D. and M.D. initiated and coordinated the project. M.D., M.T., S.T., and J.D. made the qualitative analysis. M.D. drafted the manuscript. M.D. and J.D. contributed to the literature review. C.M., C.D., P.F., and M.L. were involved in data collection and critically revised the article. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Financial support

This research was supported by grants from the APICIL Foundation, the LEEM Foundation, and the MUSTELA foundations.

Competing interest

The authors declare none.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.