The Electroconvulsive Therapy Accreditation Service (ECTAS) was launched in May 2003. Its purpose is to assure and improve the quality of the administration of electroconvulsive therapy. Participating clinics undergo a process of self- and peer-review. The Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Court of Electors will award an accreditation rating to clinics that meet essential standards; this accreditation will last for 3 years, subject to annual self-review. Participating clinics will also receive feedback and advice about local strengths and areas for improvement. The accreditation service is endorsed by the Royal College of Nursing and the Royal College of Anaesthetists and has the support of the Healthcare Commission in relation to English services. Clinics that participate in ECTAS will be listed on the College website, with the accreditation rating awarded.

The need for a quality assurance system

Although electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) remains controversial, evidence supports its effectiveness in treating depression (UK ECT Review Group, 2003). The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) has endorsed its value, albeit with recommendations restricting the type and severity of conditions for which it should be prescribed (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003). The major threat to the continued use of this therapy is not doubt about whether it is a useful treatment option, but concern about how it is administered. A warning from an editorial in The Lancet in 1981 is as relevant today as it was nearly 25 years ago: ‘if ECT is ever legislated against or falls into disuse it will not be because it is an ineffective or dangerous treatment, it will be because [of a failure] to supervise and monitor it correctly’ (Lancet, 1981).

Regulation or accreditation of ECT was first proposed after the last national audit (Duffett & Lelliott, Reference Duffett and Lelliott1997, Reference Duffett and Lelliott1998) which, like an earlier survey (Reference PippardPippard, 1992), found deficits in the quality of administration of this therapy. The potential impact of these deficits has been highlighted by the NICE guidance linking efficacy and side-effects of ECT to the method of its delivery (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003). Short-comings have also been found in the way in which information is provided to patients and consent is obtained; half of those undergoing ECT reported that they had not been given an adequate explanation (Reference Rose, Fleischmann and WykesRose et al, 2003). These problems in quality are in the context of testimonials that suggest that many ECT clinic staff work in isolation, with little communication with other clinics.

The Royal College of Psychiatrists Special Committee on ECT has been active in improving the administration of ECT for more than a decade. It published the ECT Handbook in 1995 (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1995), and provides training and advice. The Committee is a multiprofessional group, including anaesthetists and nurses as well as psychiatrists.

Aims of ECTAS

The ECT Accreditation Service will accredit both National Health Service and independent clinics in England, Ireland, Northern Ireland and Wales that meet explicit standards. The service also aims to foster learning and communication between clinics, and to create a national network to support working in the clinics, by involving them in the process of peer review and by:

-

• maintaining a database of standards in the administration of ECT;

-

• facilitating an e-mail discussion group;

-

• organising an annual members’ forum.

The standards

The accreditation standards for electroconvulsive therapy have been drawn from the ECT Handbook (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 1995), the NICE Technology appraisal (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003), the Scottish national audit (CRAG Working Group on Mental Illness, 2002), the systematic review of the efficacy and safety of ECT in depressive disorders (The UK ECT Review Group, 2003) and the systematic review of patients’ perspectives by Reference Rose, Fleischmann and WykesRose et al, 2003. The standards have been the subject of extensive consultation with all professional groups involved in this therapy and with service users and their representative organisations, and have been piloted during ‘mock’ visits to two clinics. The current version can be viewed on the College website at www.rcpsych.ac.uk/cru/ECTAS.htm. The standards are organised into the following sections:

-

• the ECT clinic and facilities

-

• staff and training.

-

• assessment and preparation

-

• consent

-

• anaesthetic practice

-

• the administration of ECT

-

• recovery, monitoring and follow-up

-

• special precautions.

These standards relate to the process of administration of ECT and to the facilities; they do not consider the quality of clinical decisions about which patients should be given this therapy.

It is highly unlikely that any clinic would meet all of these standards. To support their use in the accreditation process, each standard has been categorised as follows:

-

(a) type 1: failure to meet the standard would result in a significant threat to patient safety or dignity and/or would breach the law;

-

(b) type 2: standard that an accredited clinic would be expected to meet;

-

(c) type 3: standard that it would be desirable for a clinic to meet.

The accreditation process

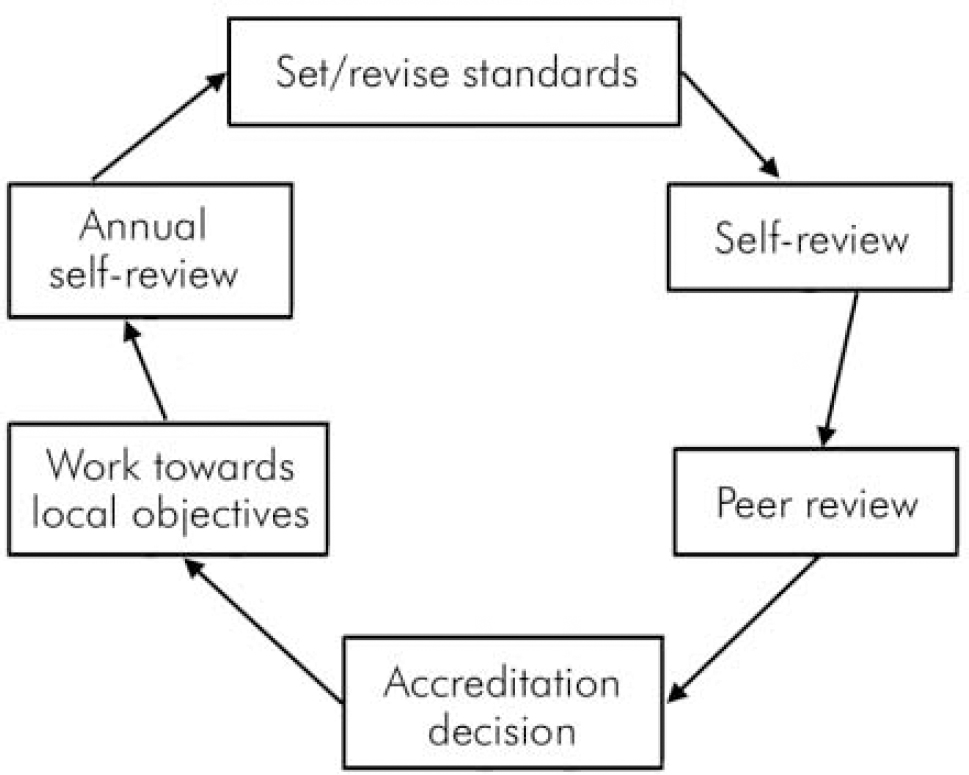

The ECTAS standards have been adapted into a range of data collection tools. Data are collected during a 3-month self-review period followed by external peer review, as part of a cycle (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. The accreditation cycle.

The process incorporates elements that research has demonstrated to be effective in bringing about quality improvement (Reference RolandRoland, 2001); these include the use of peer support, the accreditation cycle, active feedback and encouragement to identify and prioritise problems, and the setting of achievable targets for change.

Self-review

The first phase, self-review, provides an opportunity for the clinic staff to reflect on their practice, review procedures in relation to the standards, and address any deficiencies in preparation for accreditation. During the self-review, data are collected using a range of methods tailored to the different standards. These include a clinical audit of patients’ notes, staff and patient questionnaires, and the systematic observation of treatment sessions.

External peer review

After the self-review data have been returned to the College Research Unit and collated, a team consisting of three or four members of staff from other clinics will visit to validate the findings. This visit also provides an opportunity for discussion and for the review team to share ideas, make suggestions and offer advice. A lead reviewer will oversee the day to ensure that, as well as being rigorous, the visit is constructive and supportive of clinic staff. The first cohort of 40 lead reviewers, which includes psychiatrists, nurses and anaesthetists, has already been trained in the accreditation process.

Accreditation decision and feedback

A report will summarise the findings from the self- and peer reviews and identify strengths and areas for improvement. This will be sent to the service concerned and considered by the ECTAS Accreditation Advisory Committee, which will make a recommendation about the clinic's accreditation status. This recommendation will be ratified by the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Court of Electors. There will be four categories of accreditation.

Category 1

Category 1 is ‘approved with excellence’. The clinic:

-

• meets all type 1 standards;

-

• meets all type 2 standards (or meets most, with a clear plan of how to achieve the others);

-

• meets many type 3 standards;

-

• is likely to have excelled in other ways, such as research, audit or teaching.

Category 2

Category 2 is ‘approved’. The clinic:

-

• meets all type 1 standards;

-

• meets the majority of type 2 standards;

-

• meets many type 3 standards.

Category 3

Category 3 is ‘approval deferred’. The clinic:

-

• fails to meet one or more type 1standards, but demonstrates the capacity to meet these within a short time;

-

• fails to meet a substantial number of type 2 standards, but demonstrates the capacity to meet the majority within a short time.

Clinics in this category will have the opportunity to take action over a 6-month period to demonstrate that they now meet the criteria for category 2 approval.

Category 4

Category 4 is ‘not approved’. The clinic:

-

• fails to meet one or more type 1 standards and does not demonstrate the capacity to meet these within a short time;

-

• fails to meet a substantial number of type 2 standards and does not demonstrate the capacity to meet these within a short time.

Clinics in this category will be advised that, in the opinion of ECTAS, electroconvulsive therapy should not be administered in the clinic until these standards have been met.

Accreditation period

Clinics that satisfactorily complete the initial self- and peer review process are accredited for 3 years. Maintenance of a clinic's approved status is conditional on the satisfactory completion of annual self-review.

Organisation of ECTAS

The Royal College of Psychiatrists provided funding to establish ECTAS, and the College Research Unit manages the initiative. The ECTAS team is advised and supported by a reference group which has cross-representation from the ECT committee. The Accreditation Advisory Committee, which receives reports and makes recommendations about accreditation status, is chaired by Dr Chris Freeman. Both the reference group and the Committee are multiprofessional, with representatives from the Royal College of Nursing and Royal College of Anaesthetists.

As well as the endorsement of the Royal College of Nursing and Royal College of Anaesthetists, ECTAS has support of the Healthcare Commission. The latter recommends that independent-sector psychiatric hospitals in England that have ECT clinics should participate in ECTAS. The Irish College of Psychiatrists is actively involved in promoting ECTAS to services in Ireland, and similar links are being established in Northern Ireland and Wales.

Progress

The Accreditation Service was launched on the same platform as the NICE Technology Appraisal of ECT (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2003), on 1 May 2003. Twenty-five clinics subscribed to the first wave of accreditation. This commenced in October 2003, with the first peer review taking place in January 2004 and the first clinics being accredited in late spring 2004.

Benefits of membership

Membership of ECTAS is voluntary. In keeping with successful quality improvement initiatives, the impetus for the first wave of members came from the staff working in the clinics, not from senior managers. Accreditation recognises the achievement of the clinical team, and the local reports provide clear advice about areas for improvement. Membership of the e-mail discussion group and the annual forum will promote better communication between services, while the peer review process allows staff to visit and learn from other services. As it develops and more clinics become accredited, regulatory bodies — including the College, which approves training schemes — may come to expect that services that provide electroconvulsive therapy meet ECTAS standards.

In time, ECTAS should also help inform patients’ treatment decisions. An accreditation rating will reassure patients, and referrers, that an ECT clinic not only meets certain standards but is also striving to improve. To support this, all clinics participating in ECTAS will be listed on the Royal College website, with the accreditation rating awarded.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.