Introduction

Keith Swanwick has had an important influence on my life as a music educator both as teacher and academic. In particular, this is manifest in my ongoing concern for ‘how music works’ and the implications for practice, which are so brilliantly thematised in Swanwick’s celebrated collaboration with June Tillman.

As a student teacher I was introduced by enlightened tutors to Swanwick’s early work and the seminal A Basis for Music Education was published in 1979, the year of my graduation. As an emerging meta-theory, this is one of the most important books on music education that I have read. Later in my career, as a more experienced music teacher and postgraduate, I was taught by Swanwick and introduced to his ever-developing ideas including his work with Tillman. Furthermore, the first national curriculum for music in England (DfES, 1992), based on the triumvirate of listening, composing and performing, was a thinly disguised, if unacknowledged, version of his C(L)A(S)P parameters.

I am still drawn to the wide-ranging and overarching coherence of Swanwick’s work and in the context of his obvious ‘care’ for music in the music classroom; his meta-theory remains a very attractive proposition for progressive music teachers.

Whether you agree with him or not, Swanwick’s unprecedented research and scholarship, his creative and illuminating appropriation of authors such as Popper (evolutionary epistemology) and Langer (on the significance of music), almost single-handedly brought into existence the field of music education as an area of academic interdisciplinary study in the UK. There were other contemporary giants, such as John Paynter but nothing on this scale or breadth.

A central and seminal publication in this legacy is Swanwick’s work with Tillman on the sequence of musical development based on an empirical study of children’s compositions (Swanwick and Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986). The underpinning data, derived from Tillman’s PhD thesis and from which the famous ‘spiral’ emerged, proved to be so significant to our understanding of developmental theory and practice in music education.

This current paper will aim to place the ‘spiral’ in the wider context of Swanwick’s work, to trace ideas that fed into it, those that were developed from it and that now represent his unified meta-theory. It will also explore some of the critical issues that have been identified with the meta-theory and how these have informed the ever-developing field of music education. Swanwick is at heart a Popperian and while music education moves on (not always in good ways), his contribution over the last 60 years or so has been at the heart of an evolutionary epistemology for our understanding of music teaching. So where exactly does the Swanwick/Tillman spiral stand in relation to the wider meta-theory of music education?

Claims made for the spiral by Swanwick and Tillman

The explicit claims made for the spiral by Swanwick and Tillman in the original article, and its implications for music education, are in fact quite modest. First, they suggest that it can inform us in relation to planning for curriculum progression, that is, given what they uncovered about musical development the spiral can be used to ‘focus our curriculum activities towards broad aspects of musical development’ (Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986: 335).

Second, it can be used to recognise and plan for individual development where, by understanding a child’s developmental place on the spiral, the teacher is able ‘to choose material or suggest an activity that may have more personal meaning and consequence for the individual’ (ibid 336). Actually, tucked away in their second implication is at least one more of huge importance: that the spiral might help us to identify ‘what is musical about music’ (ibid 336), of which more later.

Thirdly, based on the assumption that the spiral is both developmental and experiential, then ‘overall development… is reactivated each time we encounter a new musical context’ (ibid 336). This, they suggest, is an important understanding for teachers when initiating activities or new musical experiences.

These conclusions outlined by Swanwick and Tillman are a glimpse of where the spiral came from and where it was to go, and this is the focus of the current article. Key to its relationship with what went before and what came after is a crucial qualitative orientation. The shifts between the layers and from one side of the spiral to the other are not recognised by criteria that chart ‘more of’ but are qualitative changes in the ways in which children developmentally engage with music. Most importantly, children’s actual experience of music is also qualitative, and the spiral specifically outlines the qualities of their creative engagement with music.

As a music educator I have found the qualitative nature of the descriptions resonant with my own theory and practice of music education. For example, the spiral aimed to account for what is musical about music and in spite of any critical issues, which are explored later, this qualitative focus on music (and its meaning) remains important to me. While this hugely significant nuance has not always translated into wider classroom practice or policy, it is certainly the key to the meta-theory to which we now turn.

More than just a spiral: Swanwick’s meta-theory

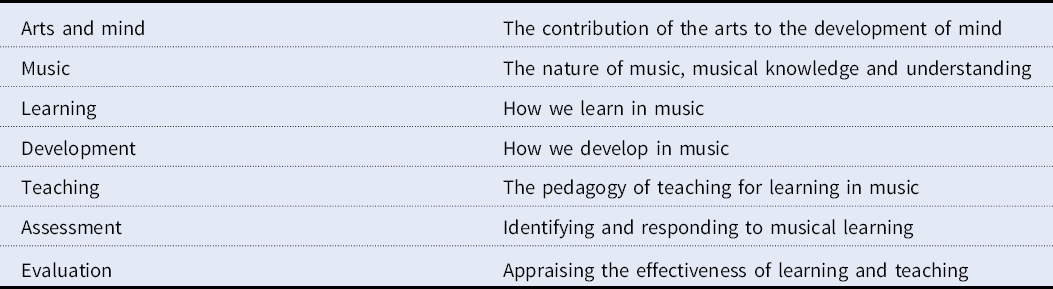

The qualitative values of Swanwick’s meta-theory can be seen in a coherent and logically connected set of themes, which in the spirit of the spiral itself he re-engaged with increased richness over time. These themes are outlined in Table 1, and the purpose here is to draw connections between them, to understand what informed the spiral and how its ideas moved on after publication. It is perhaps invidious to separate in this way given the high levels of integration across Swanwick’s ideas, and yet the categories enable us to analyse the overall shape of his work as an overarching meta-theory, and the centrality of the spiral within this.

Table 1. Themes in Swanwick’s Meta-Theory

The arts and mind

For Swanwick, the arts have common roots in mind and where education ‘has to do with developing understanding, insightfulness; qualities of mind’ (Reference SWANWICK1983: 9). Swanwick is concerned with how this might be translated into practice ‘in such a way that the arts can be true to themselves…’ (ibid 26). This is the crux of his starting point: that arts education should be driven by their essential nature and their role in the expression and education of mind.

Drawing particularly on the work of Piaget (Reference PIAGET1951), Swanwick (Reference SWANWICK1983, Reference SWANWICK1988) posits the essential interconnectedness of mind, arts and education through a concept of ‘play’ which can be characterised by mastery, imitation and imaginative play. These concepts end up being the essential layers of the spiral infused with the back and forth of assimilation and accommodation that achieves a developmental equilibrium in the development of mind (through the arts). This is a balance between the arts as a creative development of new relationships in our world (imaginative play) and as a representation of our world (imitation). This approach is key to the proto theory that underpins the spiral and the tools later used to interpret Tillman’s empirical data.

Locating music in the wider context of the arts and mind is important. There is a notion here that there are deep rooted consiliences between all disciplines and symbolic modes through which we create and understand our worlds (Philpott, Reference PHILPOTT, Cooke, Evans, Philpott and Spruce2016). This is a more enlightened and nuanced position than the populist and protectionist narrative (‘music is special and good for us’) that is prevalent amongst some music educators, especially at a time of pandemic.

Furthermore, Swanwick’s psychological account of the relationship between the arts, mind and education asks us to consider complexity and subtlety in contrast to oversimplified interpretations of neuroscience promoting ‘principles of instruction’ and where distorted accounts of knowledge and learning are applied to the arts and education (see Department for Education 2021).

Finally, in locating the arts (and their essential nature) in the wider development of mind, Swanwick provides a rich alternative to utilitarian and instrumental approaches to education. In a famous paraphrase of an obscure 1904 policy document, he suggests that the development of mind is: ‘For the work of life, not the life of work!’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 155).

Music

Probably the most important cog in understanding the Swanwick meta-theory is his work on what is musical about music. Questions arise such as: What is the nature of music? What does music mean? What does it mean to know and understand a piece of music? What is the nature of musical knowledge?

The answers to these questions are key to understanding exactly what Swanwick and Tillman were observing in the empirical data collected from children’s un-notated compositions, that is, the development of ‘what’. In answering this Swanwick has separately developed an epistemology for music drawing on musicologists and philosophers.

The nature of Swanwick’s epistemology is based on understanding the ways in which music makes meaning. In A Basis for Music Education (Reference SWANWICK1979), he uses the work of Suzanne Langer (Reference LANGER1942) to explore how music makes meaning for us through its significance as a metaphor (and symbol) of our dynamic felt and conscious world, for example, where music and the world of feeling share shapes and gestures such as ebb and flow, tension and release.

Swanwick’s theory is further enriched through a psychological account of how these metaphors are created through, for example, Meyer’s (Reference MEYER1956) suggestion that meaning is made in music through the inhibition of an expectation or tendency. These symbolic and metaphorical meanings permeate the musical layers of materials, expression and form in the spiral of development, which in turn correspond with the psychological layers of mastery, imitation and imaginative play.

In Teaching Music Musically (Reference SWANWICK1999), further detail is developed in relation to the metaphorical transference of music into meaning and its development in the spiral, when:

-

‘Tones’ (materials) are heard as ‘tunes’ (expression)

-

‘Tunes’ (expression) are heard together in new relationships (form)

-

Music informs the ‘life of feeling’ (value).

The important point here is that what is musical about music is its meaning and our understanding of it: knowledge ‘of’ music. This is a challenging idea in the context of musical knowledge commonly being seen in terms of knowing about things, knowing how to do things, knowing how to read and write notation, knowing how to use analytical concepts, etc. When proposing objectives for learning musical knowledge in the classroom, Swanwick outlines a hierarchy that specifically places a knowledge ‘of’ music as the ‘ultimate aim’ (Reference SWANWICK1979: 67). This knowledge ‘of’ music, what Reid (Reference REID1986) calls embodied meaning, involves us having a personal relationship with music in the same way that we might know a town or a person.

The practical manifestation of Swanwick’s approach to knowledge is to be found in his C(L)A(S)P model of the parameters of music education (Reference SWANWICK1979: 45) and the associated hierarchy exemplified by the brackets (literature studies and skill acquisition). This was an influential model on national policy as seen in the first version the national curriculum (1992) and its subdivisions of Listening (audition for Swanwick), Composing and Performing. However, the radical epistemological implications of the hierarchy of musical knowledge were not followed up in the implementation of the national curriculum. Meaning and qualitative musical knowledge was a step too far for national policy.

This is such a crucial theme in Swanwick’s work that he further refined it in what he considers his magnum opus Musical Knowledge (Reference SWANWICK1994). Here, amongst other things, he explores the dialectical relationship between intuitive knowledge (knowledge ‘of’ music) and analytical knowledge (know-how) which is a further manifestation of moving from one side of the spiral to the other (assimilation to accommodation) as musical knowledge develops in children.

This concern with meaning as being central to musical knowledge and music education remains challenging to this day. As we shall see, ideas have moved on in this regard (not always in a forward direction) and yet musical meaning at the heart of theory was and still is sadly rare.

The qualitative orientation is, for Swanwick, a focus on what makes music ‘musical’ and is central to the way in which we conceive learning, teaching and how we identify musical development in children.

Learning

Nothing of what has been said thus far need necessarily have anything to do with formal music education. Clearly music and the arts are part of the development of mind outside of education in the process of enculturation, and in this sense we might consider ourselves lucky that we do not only rely on formal education to develop musically.

Children intuitively develop their knowledge ‘of’ music and it is at least theoretically possible for us to have highly developed relationships with music without any formal understanding of ‘know how’, although there is a sense in which ‘know how’ can also develop intuitively. For example, we can ‘know’ the unfolding of ‘Confutatis’ in Mozart’s Requiem Mass and be able to describe it or compose in response to it without being able to formally ‘name’ its expressive devices or structure.

Whether in informal or formal situations, the spiral can tell us something about the ‘how’ of musical learning and here Swanwick adapts the theory to embrace what he calls musical encounter (intuitive experience) and musical instruction (analytical experience) to understand this:

‘I would suggest that this tension between instruction and encounter is both inevitable and fertile. These apparently contradictory aspects of human learning are the positive and negative poles between which the electricity of educational transactions flow. Encounter and instruction correspond with the left and right of the musical spiral, with the natural ebb and flow of musical experience’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 135).

However, the instruction (right) side of the spiral does not necessarily need to be managed by a formal teacher. It could be that the taught moment is one of self or peer instruction. In this sense, the spiral is a precursor to Folkestad’s (Reference FOLKESTAD2006) work on formal and informal moments of learning where the informal moment has an emphasis on playing or making music (encounter) and the formal moment on learning how to play music (instruction). This productive tension underpins musical learning outside of school and also potentially the pedagogy of music teachers in school as we shall see later.

At the heart of the spiral then is not just what we learn and its developmental sequence, but also implications for how we learn in a wide variety of musical contexts. However, the spiral also has embedded within it the priority of musical encounter over instruction. While it is at least theoretically possible for the former to exist independently of the latter (as part of an intuitive musical understanding), instruction in the more formal (analytical) sense is contingent upon encounter for a musical education.

Development

While the spiral speaks of so much more than musical development, the original article is an ample description of this. However, having reached the central point in our survey of the meta-theory we can summarise that: there is a strong structural relationship between the arts and mind; development in the arts (and music) is educative of mind; at the heart of this development is the essential nature of the arts as ways of making meaning; that knowledge ‘of’ this meaning is central to the various layers of musical experience and our development through them; that musical knowledge can develop both in and out of school through a productive tension between encounter and instruction, intuition and analysis (the to and fro, back and forth of the spiral).

It is also worth reiterating how the spiral itself reflects the shape of musical experience (i.e. all developmental layers are ever present during any musical experience) and is also a model for how we take meaning from new and unfamiliar musical experiences. However well developed we are, the model predicts that we re-engage with the lower levels of the spiral as we make sense of new music.

Having come to this understanding, it is clear that the spiral of development proposed by Swanwick and Tillman is a multi-dimensional matrix and has complexity and nuance that speaks to the totality of music education. This is its central place in the wider meta-theory.

We now turn to the implications of the meta-theory for pedagogy, assessment and evaluation.

Teaching

There is much by way of a conflation of teaching and assessment in Swanwick’s work and he famously argued that ‘to teach is to assess’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 149).

The bald implications for classroom pedagogy lie in the productive tension between encounter and instruction, intuition and analysis, that is, when teachers are able to establish this in their classrooms they will facilitate learning in and through the qualitative layers of musical knowledge. However, the spiral speaks of some important implications in this regard. First, given the hierarchical significance of knowledge ‘of’ music, there is an implied movement from the left to the right, that is, from encounter to instruction, from intuition to analysis. While more ‘formal’ knowledge has the power to inform our intuitive understanding of music, it is the latter which is the ‘ultimate aim’ of music education with consequences for pedagogical sequencing. In short, musical encounters need to be built into classroom experience as a basis for moving from left to right. While Swanwick agrees that it is tough to guarantee musical encounters, and that they are more likely to naturally occur outside of school, he suggests that:

‘…we can try… to bring about a state of readiness, so that encounters become more likely and more significant….to increase the likelihood of these encounters…’ (Reference SWANWICK1988, 138).

This state of readiness to facilitate encounters is most likely found when teachers take ‘care’ of music, and Swanwick outlines three important principles of care in music education:

-

Care for music as discourse: where ‘the aim of the music teacher is to bring music from the background into the foreground of awareness’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 44)

-

Care for the musical discourse of students: where ‘Each student brings a realm of musical understanding into our educational institutions’ (ibid: 53)

-

Care for fluency first and last: ‘musical fluency takes precedence over musical [notational] literacy’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 56).

These principles of care derive directly from the epistemology that surrounds the spiral and for me, have had (and continue to have) a significant impact on my writing and practice in music education.

Assessment

There are obvious implications of the spiral for summative assessment and the layers can be used to appraise where individual children are (qualitatively) located on the spiral when engaging with materials, expression, form and value. Swanwick (Reference SWANWICK1999) spent some time producing qualitative criteria statements across different types of musical engagement that can be used for this purpose.

Swanwick also adapted criteria derived from the spiral to mirror the quantitative levels found in the national curriculum (SCAA, 1996) and examinations (Swanwick, Reference SWANWICK1988 and Reference SWANWICK1994). While it is clear that Swanwick wanted to ameliorate a policy that was not sympathetic to the qualitative, as an exercise this tended to erode the essential nature of the layers through appearing to take up an accumulative tone.

Of greater potential for me, is the use of the layers in formative assessment for learning, and this is where there is a significant (and important) conflation of assessment and pedagogy in the meta-theory.

At the heart of this is Swanwick’s belief in music education as musical criticism, the formative and constructive dialogue between teacher and student:

‘…an alternative vision of assessment as an extension of teaching, assessment as criticism; appraisal of the folio, the poem, the dance, the improvisation, the performance, the composition, the design, the artifact; all these objects and events in the real world’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 150).

Given the shape of musical experience and knowledge wrapped up in the spiral, it is a dialogue that can take place around the layers themselves, and Swanwick boldly asserts:

‘These are the dimensions in which all musical criticism and analysis is framed, areas in which philosophers of art, aestheticians and psychologists have laboured for centuries. It seems not unreasonable to have them infiltrate our thinking on assessment…’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 80).

Furthermore, this is not just a discourse of words but a discourse within and between the layers of music and where music ‘is a medium in which ideas about ourselves and others are articulated in sonorous shapes’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 2).

This is an attractive and coherent notion of music education conceived as criticism both about and in music and founded on the shape of musical experience embodied in the spiral. Here again, ‘to teach is to assess’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 149).

Evaluation

Finally, and to complete the logic of the meta-theory, the spiral also has implications for evaluating the effectiveness of teaching, learning and assessment. For Swanwick, this is an issue of quality where assessment information is used to understand the development of qualitative musical understanding.

Swanwick argues that in order to do this we need a ‘valid assessment model that is true to the rich layers of musical experience’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 84) and that this is only possible ‘with the aid of a half-way decent definition of musical understanding, a theory of musical mind’ (Reference SWANWICK1999: 87).

The issue of evaluation then brings us full circle back to where we started in this analysis of the meta-theory. To evaluate our work as educators we can ask ourselves: as a consequence of what has gone on in our classrooms how has the (musical) mind developed? Here the spiral is the benchmark of evaluation and, Swanwick would argue, without such a ‘theory’ how would we know the answer to this question?

Some critical issues

The pervasive consistency of Swanwick’s meta-theory throughout his work has, in different measures, had an impact on music teachers, the field of music education and national policy, although these three are by no means mutually inclusive.

However, despite its theoretical elegance and coherence there are a series of related issues, which can be seen as being either terminally schismatic or part of the wider evolution of the field, and it is to these issues that we now turn.

While this is by no means an exhaustive account of critical issues, four related areas will be examined:

-

Swanwick’s musicological sources and a partial account of musical meaning;

-

problematic claims for universalism in the way musical meaning is made;

-

the issue of invariance in meta-theory;

-

musical criticism without criticality.

Given the centrality of the spiral to the meta-theory, these are issues that equally apply to it.

Musicological sources

Issues with the musicological sources employed by Swanwick have been raised by, amongst others, Elliot (Reference ELLIOT1995), Shepherd (Reference Shepherd, Shepherd, Virden, Vulliamy and Wishart1977) and Green (Reference GREEN1988).

Elliot (Reference ELLIOT1995, Reference ELLIOT2000) is concerned that in relying on the work of authors such as Langer, he (and others such as Reimer, Reference REIMER1989) is committed to a concept of aesthetic listening where musical works are seen autonomous objects with meaning wrapped up in the internal properties of the music. Furthermore, Elliot argues, this version of musical meaning is rooted in the western classical tradition of the 18th and 19th centuries.

While there is some substance to this, Elliot misrepresents Swanwick through a limited account of the scope of his position. For example, Swanwick’s concern for the creative responses of children in the making of musical meaning illustrates a far wider reach than that recognised in Elliot’s criticism.

Of course, Elliot himself produced what is a rival ‘praxial’ theory of music education in the late 20th century, and yet while he provides a hugely detailed cognitive framework for the philosophy and practice of music education, there is little by way of how music makes meaning. By engaging with this Swanwick stimulated debate in the field, and the import of meaning in music education is still being worked out (Philpott, Reference PHILPOTT2021).

In particular, Elliot’s issue is with Swanwick’s appropriation of Langer. Elliot (Reference ELLIOT1995) argues that Langer’s assumption that music is mostly significant to our inner felt worlds has been widely discredited and thus also redundant as a theory of musical meaning for music education. Notwithstanding that Elliot does not start from a position of meaning in his own praxial philosophy, it is clear that music does have an inner dimension and further constructive debates with Swanwick on this issue were conducted with Shepherd, Vulliamy and Green.

Shepherd argues that:

‘restricting musical meaning to the ‘inner life’, as Langer does, and thereby denying an ‘outer’, transcendent or social meaning… seems to be a product of traditional industrial epistemology as witnessed in the inner-outer opposition’ (Reference Shepherd, Shepherd, Virden, Vulliamy and Wishart1977: 66).

Furthermore, by relying on properties such as ebb-flow, tension and resolution this version of musical meaning is rooted in the tonality of the western classical tradition, which for Shepherd is the musical embodiment of the ‘traditional industrial epistemology’.

Shepherd argues for the importance of the outer social dimension to musical meaning by claiming that ‘the organization of musical structures is ultimately a dialectic correlate of the social reality that is symbolically mediated by and through the music of a particular society’ (Reference Shepherd, Shepherd, Virden, Vulliamy and Wishart1977: 84)

For Swanwick, this approach to meaning is unduly referential (and relativist) promoting as it does the direct relationship between music and the structure of society. He believes that music functions in a more universal way ‘to which we are able to relate across historical time and cultural differences’ and furthermore ‘we can be responsive to music that is from a quite alien social structure’ (Reference SWANWICK1979: 110). The reason we can do this, he suggests, is because of ‘deep structures’ in the making of musical meaning, that is, ‘of tension, of resolution, growth and decay, a feeling of weight space and size…’ (Reference SWANWICK1979: 111). These are the very same deep structures outlined by Langer.

While Vulliamy and Shepherd (Reference VULLIAMY and SHEPHERD1984) refute the charge of music only being referential of the social they maintain their position on cultural and social relativism and in the context of Swanwick promoting the presence of deep universal structures in musical meaning, this is a major schism for music education (and indeed for much western thought).

Lucy Green (Reference GREEN1988) aims to resolve this schism by theorising the relationship between inherent musical meanings (promoted by Langer) and the delineated meanings (focused on by Shepherd). Green critiques Swanwick for not recognising ‘the dialectical and logical nature of music’s relationship to its own internal structure on the one hand, and to its social structuration on the other’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 96). Green further argues that the dominant ideology of western classical music has the power to ‘fetishise’ these dimensions to meaning and thereby hierarchically structure what counts as ‘good’ music.

‘Great music is made to appear, and is required to appear, eternal, natural and universal: or autonomous. Poor music is rooted in society and allowed nothing but interfering delineation…to rid music of all its social constructs, is at the heart of musical ideology, the bourgeois aesthetic of autonomy and fetishism’ (Reference SWANWICK1988: 101).

For Green, what counts as music has huge implications for the access and distribution of success in the music classroom and can confound inclusion and social justice. Such a perspective takes on increased significance at a time of calls for the decolonisation of the music curriculum.

Universalism

Behind the debates outlined above is the tension between universalism and pluralism. This was illustrated in a brief but turbulent debate Swanwick had with Robert Walker.

Walker (Reference WALKER1996) reiterates Green’s point that the culturally specific features of western thought (and music) have been conflated with what we might regard as being the universal, and even words such as ‘music’ itself are ‘culturally laden with western traditions of the last several hundred years’ (Reference SWANWICK1996: 8). Walker promotes a music education in which there would ‘be no reliance on an essentialist notion of the autonomous, culturally transcendent, generically expressive qualities of sound matched by a generic human aesthetic response to such sounds’ (ibid 12).

In his response to Walker, Swanwick argues a familiar case about designing ‘principles for music education [which] may be shared by teachers in very different cultural and educational settings’ (Reference SWANWICK1996: 16). Walker sees this as further evidence of ‘a universal cognitive position for human minds’ and as such putting music education ‘back in its western prison’ (Reference WALKER1998: 61).

Meta-theory and invariance

Universalism and associated meta-theories are of course ripe for post-modern critique. Swanwick seems to suggest that his ideas apply across human cultures and that they are invariant in structure, that is, we might expect to observe the spiral the world over. Quite apart from what Lyotard (Reference LYOTARD1984) describes as the post-modern incredulity at meta-narratives, the philosophical schism is outlined by Walker when he suggests: ‘Cultural difference means cognitive difference which does go hand in hand with social and musical difference’ (Reference WALKER1998: 60).

Criticism but not criticality

It would be fair to say that the ‘social turn’ to music education and its inherent critique of the ideology of western classical music has not been predominantly focused on Swanwick’s work. This has been saved for versions of music education that more explicitly promote knowledge of the ‘canon’, concepts and skills above what is most musical about music. In this particular debate, Swanwick is a progressive and massive ally.

However, the ‘social turn’ does point to ideological values that, perhaps unwittingly, permeate the theory and practice of music education and that otherwise might appear to be progressive in nature. Depending of course on your starting point Swanwick’s meta-theory appears to fall into this camp. While it is founded on music education as musical criticism it can be argued that it is criticism without criticality, that is, that given the sealed and insulated nature of the meta-theory it does not have the critical tools (or disposition) to understand or deconstruct its own premises. This is criticism without critical musicology or critical pedagogy.

The spiral and the critical issues

Given that the Swanwick–Tillman spiral has a central position in the meta-theory it is clear that it is implicated in all of the critical issues noted above and the following interrelated questions arise in relation to it:

-

Is the spiral, as conceived by Swanwick and Tillman, based on a limited conception of musical meaning or does it reveal the deep structures of meaning?

-

Is the spiral prejudicial to an understanding of cultural pluralism or does it chart universal principles of musical development?

-

Does the implied invariance of the spiral mean that it cannot recognise cognitive difference across cultures or does it transcend such difference?

-

Does the spiral spawn an insulated notion of musical criticism without criticality or can it furnish a critical pedagogy?

These are crucial and fundamental questions which arise as a consequence of developments in the theory and practice of music education since the publication of the original Swanwick/Tillman article and indeed the development of the wider meta-theory. At face value, they may appear irreconcilable and yet in another sense they are the issues that have underpinned philosophical thought for thousands of years, and we learn to live with them.

Concluding discussion

Where then does all this leave a long-time supporter of Swanwick? What does it mean for a music teacher whose writing and practice have been heavily influenced by his work, but who has also been convinced by the social turn? From a very personal perspective, there are two main ways to view this conundrum in light of the theoretical schism between different ways of viewing the world.

First, Swanwick’s work can be seen as part of the evolutionary epistemology of music education and as a Popperian I am sure that he would accept this as quite natural. Work goes on although, in a post-modern context, with little purporting to be a meta-theory.

For example, there is an increasing awareness that we might turn to critical musicologists for our understanding of how music works before we design ways to teach it. Writing in the field of semiotics and hermeneutics has the potential to inform not only a musical music education but also one of criticality (Kramer Reference KRAMER2011; Philpott Reference PHILPOTT2021). Here is an interpretative and critical epistemology to inherent and delineated meanings that, while recognising relativism, does not infer meaninglessness.

There is also much by way of theorising around the ways in which we engage with music through a pluralism of creativities (Burnard, Reference BURNARD2012) that provide an alternative to universal accounts of how meaning is made.

In the realms of pedagogy and assessment, there is important work focused on the making of meaning in the classroom through, for example, dialogic (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE, Benedict, Schmidt, Spruce and Woodford2015) and self-directed pedagogies (Green, Reference GREEN2008), which recognise pluralism and the critical complexity of relationships between music, individual and society.

These approaches can be embraced by a critical pedagogy (Philpott with Kubilius, Reference PHILPOTT, KUBILIUS, Benedict, Schmidt, Spruce and Woodford2015) as teachers and their students become reflectively self-aware of the relationships between musical meaning, society and culture. For me, this work is not an antithesis to Swanwick but part of an evolutionary response to him.

Second, while there is much that is schismatic in this evolution, the aims of the meta-theory remain powerfully and foundationally valid. The desire to understand what is musical about music as an underpinning for music education remains, for me, the key issue in our field. This is by no means easy to write about and yet Swanwick is one of the few who have done so with eloquent conviction.

It can be argued that these foundational considerations are an immunisation against social realist accounts of education that are currently in favour and where disciplinary conceptual knowledge holds sway as ‘powerful knowledge’. In music, knowledge ‘of’ meaning can be subverted here beneath the need to learn concepts and skills, most readily seen in the UK government’s recently published Model Music Curriculum (DfE, 2021) which energetically constructs lists of content to be ‘learned’, for example, notations. Swanwick maintains that just because we can form concepts about music does not mean that it is essentially conceptual in nature and that concepts are of a second order in the hierarchy of knowledge, certainly not the most powerful knowledge. For me, this single principle continues to guide my writing and practice: the pursuit of understanding what is musical about music as being the most powerful knowledge at the heart of music education.

Swanwick’s research with Tillman yielded a seminal model of musical development and the spiral is an epistemological symbol of the meta-theory that surrounds it. Whether or not we agree with the meta-conclusions the theory continues to speak to us about the most important issues in music education. In Swanwick’s own words, his work has aimed to focus on ‘the medium of music and the qualities or elements that may be thought to constitute our experience of music, whether in active practical engagement or as ‘listeners’’ (Reference SWANWICK2016: 3).

In this regard, when considering the foundational and qualitative orientation of the spiral, we can do worse than judge any curriculum development or initiative by Swanwick’s three principles of care for music education outlined earlier. These principles are both woven and emergent in Swanwick’s meta-theory and with or without the ideological baggage I can, and do, live by them as a music educator. We do not need to subscribe to the meta-theory to agree with these principles.

As with most seminal thinkers, when the field evolves, no matter how large the paradigm shift there is something of them that remains. For this reason, Swanwick will always be important to the field of music education.