Countries witnessing rapid economic development frequently struggle to assimilate new migrants into cities. As the population of Britain’s towns doubled in size during the industrial revolution, Friedrich Engels ([Reference Engels1845] 2010) described a burgeoning urban proletariat “cast out and ignored by the class in power” (114) and living in a “state of dilapidation, discomfort, and misery” (viii). During the Great Migration in the United States, African Americans escaping Jim Crow laws met with “unwritten, mercurial, [and] opaque” resentment in northern cities; they were pushed to the margins, leading Martin Luther King Jr. to lament that “Chicago has not turned out to be the New Jerusalem” (Wilkerson Reference Wilkerson2010, 386).

Internal migrants, who number one seventh of the world’s population, face similar challenges across much of today’s Global South (Bell and Charles-Edwards Reference Bell and Charles-Edwards2013). Political exclusion is commonplace (Bhavnani and Lacina Reference Bhavnani and Lacina2015; Thachil Reference Thachil2020; Weiner Reference Weiner1978). Evidence suggests that those who shift from the countryside to cities participate in destination-area politics at lower rates than local-born residents.Footnote 1 This shortfall matters normatively, cutting against democracy’s promise of equal representation. It is also of practical consequence, as social groups not exercising suffrage experience state neglect (Fujiwara Reference Fujiwara2015).

What accounts for migrants’ underrepresentation in politics? We theorize three mechanisms by which mobility induces political marginalization. The first centers on migrants’ enduring economic and social ties to their origin regions. Migrants who maintain close links to “home” may be unwilling to refocus their political activities, opting to remain detached from political life in destination areas. Second, bureaucratic obstacles associated with participation in host regions—above all, the hassle costs of updating voter registration and navigating electoral bureaucracies—militate against engaging there. Whereas governments normally assume responsibility for initiating the registration process in advanced industrialized states, we find that 16 of the 20 most populous low- and middle-income democracies place the onus on citizens to initiate enrollment (see Supplementary Information A). Last, ostracism by local-born residents and their elite representatives could impede migrant integration (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010). “Sons of the soil” parties that vilify newcomers have sprung up in Mumbai, Karachi, and in parts of South Africa and Malaysia in recent decades (Bhavnani and Lacina Reference Bhavnani and Lacina2018). It stands to reason that migrants meeting with broad-based indifference or hostility will foresee few benefits to sinking their energies on politics in host communities.

We study the role played by these factors in undermining migrants’ political incorporation, which we conceptualize to comprise both citizen-side political engagement and elites’ readiness to include citizens in their electoral coalitions. To do so, we fielded a large randomized controlled trial in India, a leading case for evaluating the political underrepresentation of internal migrants. Our focus is on rural-to-urban migrants and the reasons why such individuals struggle to incorporate politically in countries whose demographics are being transformed by high economic growth. We evaluate a door-to-door campaign to facilitate voter registration among migrants to two cities: Delhi, the national capital, and Lucknow, which is the capital of India’s largest state and is emblematic of a class of mid-tier cities increasingly attractive to jobseekers (Thachil Reference Thachil2017). Partnering with an NGO in advance of the 2019 national parliamentary elections, we recruited 2,306 migrants who lacked local voter registration documents. Half of those who expressed an interest in registering to vote in the city were then offered intensive assistance in applying for a voter identification card that enabled them to cast a ballot locally in the upcoming polls. In addition, we built a cluster-level experiment on top of the individual-level design. Its purpose was to inform politicians in a randomly chosen subset of neighborhoods that the registration drive had taken place, and thus to test whether attaining registered status paved the way to migrants’ full-fledged political incorporation.

Previewing the results, there is little to suggest that migrants’ ongoing links to their former places of residence prevent them from incorporating politically at their destinations—our first theoretical conjecture. Asked whether they wished to register locally, 98% of eligible respondents replied “yes,” indicating that voluntary disengagement is rare in our sample. This is striking because interviewed migrants reported significant social and economic ties to their prior hometowns. By contrast, there is clear evidence to support our second theoretical claim: that bureaucratic obstacles to registering to vote hinder migrants’ electoral participation. Alleviating these constraints—by providing at-home assistance in completing and submitting voter registration documents—increased migrant registration rates by 24 percentage points and next-election turnout by 20 percentage points. It also shifted downstream outcomes, raising political interest and perceptions of local political accountability.

Does elite nonresponsiveness further undermine migrants’ local political incorporation, as our final theoretical proposition predicts? The eagerness of migrants to accept registration assistance suggests that anticipation of ostracism is not a major determinant of exclusion on the demand side. Yet, we go further to assess experimentally whether the basis for such perceptions exists. If city politicians are constrained by the antimigrant preferences of urban electorates, then learning about the mass registration of migrant voters locally should fail to influence their campaign strategies. Against this expectation, we find that electioneering increased in the vicinity of polling stations listed in our communications to candidates. As migrants found a place on local electoral rolls and politicians learned as much, candidates began soliciting migrant support. Overall, we conclude that stringent registration requirements—rather than “opting out” or expectations of ostracism by local political machines—drive the political incorporation gap between migrants and local-born residents in the fast-growing cities we study.

Our study breaks new ground. We study a “patronage democracy” where access to government benefits is intimately bound to individual voting behavior. That migrants do not always assert their political participation in their primary places of residence, despite possessing the full constitutional rights to do so, poses a significant puzzle.

Recent studies suggest that registration drives can in some cases be effective tools for spurring enrollment among unregistered citizens (e.g., Harris, Kamindo, and van der Windt Reference Harris, Kamindo and van der WindtForthcoming; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2015). Yet to date there has been negligible theoretical or empirical work on the roadblocks to political access encountered by migrants in the developing world or, indeed, by movers writ large. Going beyond prior studies, our novel cluster-level experiment evaluates the “supply side” of political incorporation—investigating whether politicians are responsive to news of the enfranchisement of a previously disempowered population group. Observational studies on enfranchisement’s effects have generated mixed findings (cf. Paglayan Reference Paglayan2021). Our layered research design enables us to experimentally probe equilibrium dynamics as new groups of voters enter the electoral fray and politicians update their campaign strategies in reaction. To the extent that these strategies entail the targeting of individualized benefits and local public goods, our study can further advance understanding of the sources of urban deprivation (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2019).

Finally, as we document, naturalized cross-border immigrants consistently vote at lower rates than native-born citizens in wealthier democracies. Across countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, turnout rates averaged 80% for native-born citizens compared with 74% for foreign-born naturalized citizens between 2008 and 2016 (OECD 2019, 128). An analogous 10 to 12 percentage point disparity existed in the United States throughout the 2000s (Wang Reference Wang2013). Analyzing data from the 2014 World Values Survey, which covered 52 countries, we find that 82% of native-born citizens report that they “always voted” or “usually voted,” compared with 71% of foreign-born citizens (see Online Appendix A). Civil society organizations advocating on behalf of Hispanic communities in the United States and Muslim communities in Europe, for example, have underscored the importance of making these groups’ voices heard in the political arena.Footnote 2 Naturalized immigrant groups may therefore also gain from interventions that are similar to the one evaluated here (Braconnier, Dormagen, and Pons Reference Braconnier, Dormagen and Pons2017; Pons and Liegey Reference Pons and Liegey2019).

Conceptualizing Migrant Political Incorporation

Before presenting our theory, we introduce the concept of political incorporation and highlight its relevance for migrants worldwide.

Critical to our conceptualization is the dual contribution of demand- and supply-side inputs in bringing about migrant incorporation.Footnote 3 On the demand side, incorporation requires migrants’ full and active participation in destination-area politics. Behaviorally, it presumes that migrants first register to vote in city-based elections—a prerequisite for subsequent participation in formal political institutions—and then turn out to cast a ballot, the fundamental democratic act. Attitudinally, it entails shifts pertaining to political interest, perceptions of political accountability, efficacy, and trust.Footnote 4 Yet citizen action alone is insufficient to bring about full political incorporation, from our perspective. For that to happen, political elites must reciprocate by treating migrants equally vis-à-vis local-born residents and by acknowledging them to be bona fide members of local electorates. We minimally expect incorporation to include outreach to migrant citizens during campaign seasons, inclusion of migrants in local networks of clientelistic exchange, and sensitivity to problems faced by migrant communities. Paying attention to these supply-side actions is essential, not the least because politicians’ failure to include migrants in local political coalitions may demotivate migrants from taking steps to participate in the first place.

Our conceptualization maps onto the empirical record. In the realm of domestic migration, there is significant evidence that mobility is associated with lower political incorporation globally. Changing place of residence in Costa Rica “disrupts” voting and is associated with an eight to nine percentage point reduction in turnout propensity (Alfaro-Redondo Reference Alfaro-Redondo2016, 73). Focusing on Turkish municipalities, Akarca and Tansel (Reference Akarca and Tansel2015) estimate a strong negative province-level relationship between in-migration and electoral participation. Gay (Reference Gay2012) shows for the United States that use of a randomly assigned housing-relocation voucher reduced the probability of voting in national elections by seven percentage points. Qualitatively, scholars have substantiated internal migrants’ relative political disengagement in Nigeria, Colombia, Ukraine, and Myanmar (see Supplementary Information B). Ample evidence also attests to politicians’ exclusionary behaviors—that is, the core supply-side impediment to incorporation. Côté and Mitchell (Reference Côté and Mitchell2016, 662–66) marshal case study evidence from Côte d’Ivoire and Indonesia, where, according to observers, politicians have weaponized sons-of-the-soil narratives to “turn the politics of resentment to their electoral advantage.” Weiner (Reference Weiner1978, 9) describes elites’ antimigrant stances in the cities of Eastern Europe following the collapse of the Hapsburg Empire.

In short, the historical and comparative case literatures bear out the two-sided barriers to political incorporation for migrants. Our next task is to explain what drives variation in this phenomenon.

Theorizing the Migrant–Local Participation Gap

We now theorize the key citizen- and politician-side constraints to migrants’ political incorporation. Regarding citizens’ constraints, we develop two main hypotheses—one centered on voluntaristic detachment, the other on bureaucratic hurdles—explaining nonincorporation. These hypotheses hew to a cost-benefit analysis of political engagement, which posits that citizens participate politically when the expected benefits of doing so exceed the expected costs (Downs Reference Downs1957).Footnote 5 Overlooked in standard models, however, are costs and benefits that fall uniquely on those who move. Regarding politicians’ constraints, our third hypothesis homes in on the electoral pressures felt by candidates to eschew migrants. Such neglectful treatment by elites has the potential to feed back into migrants’ decisions to engage politically in the city.

Voluntary Detachment

Migrants may voluntarily decline to engage in destination-region politics because they see greater advantages to remaining politically involved in their home regions. Unlike local-born residents, migrants possess a choice about where to exercise their political participation: they can do so either in their region of origin—their default option—or in the place they settle. Thus, one engagement repertoire for migrants entails delinking their place of residence (for clarity of exposition, “the city”) from their place of political participation (“the village”).

A delinked engagement strategy holds out several attractions for migrants. First, social and emotional attachments weigh against withdrawing from politics in origin areas. Political interest develops during the early, formative years of individuals’ lives and does so in specific locales—places where social pressures to participate may be felt more intensely. At the same time, migrants often find themselves socially isolated at their destinations. Among rural-to-urban migrants in China, for example, “non-kin social ties between migrants and local urban residents are limited [and] non-resident ties still make up the majority of migrant networks” (Yue et al. Reference Yue, Li, Jin and Feldman2013, 1720). This is true of cross-border immigrants too.Footnote 6 Such dislocation effects are likely to be increasing in the cultural distance between migrants and nonmigrants. Thus, social relationships—that are strong in origin areas and weaker in destinations—may prolong origin-area political participation, even after migrants move away.

Second, economic motivations could dissuade migrants from shifting their locus of political participation. Rationally, migrants with significant material assets (e.g., property) in their former homes will seek to maintain a political voice there postmigration—to ward off expropriation and other economic threats. Intangible assets provoke similar calculations. Notably, migrants may be reluctant to sever long-nurtured clientelistic relationships with origin-area politicians. These relationships profit election-minded politicians, too, who have accordingly been known to bus migrant workers back to villages at election time and to offer gifts and additional benefits to woo migrants back during polls.Footnote 7 Analogously in the international domain, Wellman (Reference Wellman2021) finds that ruling parties encourage diaspora voting when they perceive electoral advantages to doing so.

Summing up, there are compelling reasons for migrants to wish to anchor their political participation in origin regions, rather than to transfer it to their point of destination, offering an explanation for the migrant–local incorporation gap. This leads us to hypothesize that migrants who are more socially and economically attached to their places of origin will be more likely to remain politically detached in their new places of residence.

Bureaucratic Hassle Costs

A second explanation for migrants’ political disengagement emphasizes the high administrative barriers migrants face in registering to vote in destination regions. Registration involves gathering and copying paperwork and completing and submitting forms. Citizens routinely procrastinate on time-consuming bureaucratic tasks. Randomized trials of voter registration campaigns in France, Kenya, and the United States demonstrate that enrollment is sometimes—though not always—sensitive to convenience costs for the average citizen (Braconnier, Dormagen, and Pons Reference Braconnier, Dormagen and Pons2017; Harris, Kamindo, and van der Windt Reference Harris, Kamindo and van der WindtForthcoming; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2015).Footnote 8 Missing from consideration in this literature have been the particular challenges migrants confront as they grapple with electoral bureaucracies.

Why might migrants be asymmetrically hard hit by bureaucratic registration hurdles? Migrants’ difficulties may be the unintended consequence of systems designed with nonmovers in mind. First, newcomers lack familiarity with local government procedures, rules, and regulations. The everyday knowledge required to navigate local bureaucracies (e.g., knowing the location of the nearest ward office) is likely to be second nature to local-born residents but opaque to outsiders. Second, in multilingual contexts, migrants from peripheral regions often speak a different language or dialect from those living in urban centers. Migrants who struggle with foreign-language forms will be handicapped in their bid to register to vote. Third, registrants must typically provide supporting documents along with their application. Here, too, migrants lag—particularly those living in informal settlements without title deeds or formal utilities. Finally, in many contexts, migrants are shouldered with a “double-registration burden”: they are required to deregister to vote in their prior place of residence before reregistering in their destination region. Locals do not have to jump through this additional hoop.

Alternatively, bureaucratic elites may deliberately erect barriers to thwart migrants seeking to register. Bureaucratic bias against culturally distinct outsiders—or against marginalized groups overrepresented in the migrant pool—can amplify enrollment costs (White, Nathan, and Faller Reference White, Nathan and Faller2015). Bureaucrats may recognize migrants and treat them in a demeaning or dismissive way during in-person interactions at government offices. When processing documents submitted remotely, bureaucrats can use proxies such as ethnic naming conventions or addresses (along with information about neighborhood demography) to detect migrant status. Bureaucrats can then drag their feet, refuse advice, call for supplemental evidentiary documents, or deny migrant petitions on spurious grounds.

Engaging with the state is demanding for almost any class of citizens. The foregoing discussion highlights the theoretical reasons why migrants may be levied with a registration surcharge, due both to the side effects of procedures created without thought to “voters on the move” and willful attempts to suppress migrant incorporation by bureaucrats. A testable implication is that programming crafted to ease the voter registration costs borne by movers will have pronounced, positive effects on their subsequent political incorporation.

Political Ostracism

Our final theoretical perspective attributes migrants’ political exclusion to ostracism and antimigrant backlash by urban elites. Across domains, local-born residents foresee that the arrival of newcomers will heighten labor market competition, strain public services, and “dilute” the ethnocultural fabric of urban society (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2017; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). The upshot is that locals, along with their elected representatives, are prone to exhibit antimigrant attitudes. This can manifest as passive indifference: migrant entry is permitted but nothing more is done to smooth migrants’ integration or to deliver them services to which they are entitled. It can also materialize as active antagonism—for instance, through the passage of voter suppression laws.Footnote 9 These strategies are especially likely to arise under conditions of local economic scarcity (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010). In short, politicians can respond with apathy to enfranchised migrants or, in certain circumstances, by stifling migrant turnout.

Migrants may disengage politically in these environments. Those who expect to be sidelined will anticipate little gain from taking part in city politics. Migrants fearful of police harassment, additional taxes, and pogroms may prefer to live in the “shadow of the state.” Ethnographic accounts attest to these concerns. For example, Jones (Reference Jones2020, 93) finds that migrants in Guariba, Brazil “do not belong and are not entitled to make demands” on the government because “civic ostracism places them on the margins of local politics [and] they have internalized the exclusion that they experience at the hands of permanent residents.” How general these experiences are remains to be established.

There is also a subtler logic by which politicians’ uncertain beliefs about migrants’ preferences can produce exclusion. In places where antimigrant sentiment is muted, it seems intuitive that parties would help migrants register and participate. Where parties can be confident of migrants’ probable vote choice, such party-led drives to enlist migrant voters make rational sense. Yet, more commonly, migrants are unknown quantities in local politicians’ eyes. Ethnocultural dissimilarities between politicians and migrants make their partisan leanings hard to discern; the tendency for low-income migrants to reside in dense, heterogeneous informal settlements renders their political preferences less legible to urban elites; and politicians may presume ex ante that migrants’ home attachments will depress demand for city-based registration. Meanwhile, the costs of shepherding migrants through the process are high. Running migrant-focused registration drives thus carries two risks for politicians and parties: (a) newly registered migrants may not turn out to vote, meaning that scarce resources have been squandered, and (b) migrants may accept registration help but then go on to vote for a competitor. To the extent that the political preferences of local-born residents are more transparent to elites, therefore, it makes sense to focus recruitment and mobilization efforts on locals.

If it is the case that ostracism by politicians is what drives migrant nonincorporation, a testable implication follows: even upon learning that migrants are registered to vote locally, politicians will decline to bring migrants into their local electoral coalitions. This is the third hypothesis we set up our empirical approach to evaluate.

Migration and Voting in India

We now describe a study setting—India—conducive to a rigorous test of our three theoretical claims. India has 1.4 billion citizens, 900 million eligible voters, and an estimated 325 million internal migrants, comprising 29% of the country’s population (Government of India 2010). At 34%, India’s current level of urbanization is low by international standards. However, the country’s urban population is projected to grow to 590 million people by 2030, up from 290 million in 2001, and the preponderance of all new jobs generated over the next decade will be city-based (Sankhe et al. Reference Sankhe, Vittal, Dobbs, Mohan, Gulati, Ablett, Gupta, Kim, Paul, Sanghvi and Sethy2010).

India’s rural-to-urban migrants constitute a disadvantaged population category. Online Appendix B analyzes nationally representative survey data, revealing that migrant-engaged households are poorer than nonmigrant households overall and they are more likely to belong to marginalized ethnic communities—differences that underline the integration obstacles that internal migrants face.Footnote 10 A United Nations report notes that “a holistic approach is yet to be put in place that can address the challenges associated with internal migration in India” (UNESCO 2012, 2). New migrants encounter discrimination in accessing government services (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2021a), migrant slums lack basic facilities (Auerbach Reference Auerbach2019), and demands for “locals only” employment quotas and discriminatory language stipulations have been prevalent (Weiner Reference Weiner1978).

The migrant/local participation gap is stark in India. Subnational states with more migrants evince lower voter turnout (Tata Institute of Social Sciences 2015, 30). Survey data from five states suggest that between 60% and 83% of domestic migrants did not cast a ballot in at least one national, state, or local election after moving (Tata Institute of Social Sciences 2015, 32). Representative surveys collected after the 2014 national election revealed turnout to be 69% in rural constituencies, 63% in smaller cities and towns, and 57% in large metropolitan areas (Kumar and Banerjee Reference Kumar and Banerjee2017, 83).Footnote 11 Micro-level studies in Delhi identify low turnout among urban-based migrants as a prime contributor to this rural–urban turnout divide: in 2014, only 65% of recent migrants to Delhi possessed a voter ID card allowing them to vote in city elections, whereas the overall average for Delhi residents was 85%.Footnote 12 Similarly, Thachil (Reference Thachil2017) finds in a sample of Delhi construction workers that only one in five migrants had ever voted in the city’s elections. A survey of India’s five largest cities conducted after the 2019 general elections revealed that 91% of urban-based migrants in their twenties reported that they were not registered to vote in the city.Footnote 13 The de facto disenfranchisement of internal migrants has been dubbed a “serious infirmity in the electoral process of the world’s largest democracy.”Footnote 14

Case Selection

Our study was fielded in two cities. Delhi is home to 19 million residents and is India’s national capital; it absorbs more migrants than any other metropolitan area. Like other megacities, its urban landscape is dotted with jhuggi jhopri (“slum hut”) dwellings, constructed from plastic, corrugated iron, and wood. Estimates suggest that 40% of Delhi’s population comprises migrants from other Indian states.Footnote 15 Lucknow, meanwhile, has 2.8 million residents. It is the capital of Uttar Pradesh, India’s largest state. Most migrants to Lucknow are attracted by higher wages and originate from economically backward districts of the state (Bose and Rai Reference Bose and Rai2014, 53–55).

Delhi and Lucknow were chosen for three reasons. First, we heeded the call from scholars of urban politics to study not only megacities but also small and medium-sized urbanities, which, as Auerbach et al. (Reference Auerbach, LeBas, Post and Weitz-Shapiro2018, 262) emphasize, are the world’s “most quickly expanding urban centers.” The comparison of Delhi, a Tier I Indian city, and Lucknow, a Tier II city, adds crucial generalizability in this respect. Second, and at the same time, we sought a controlled comparison, opting for two locations that were broadly similar in terms of the locally dominant language used (Hindi), historical and colonial legacies, national electoral preferences, socioreligious structures, and the primary sending regions of their migrant populations.Footnote 16 Last, we built on prior migration work by exploiting the paired comparison of Delhi and Lucknow (see Thachil Reference Thachil2017).

Local Context

To contextualize our study, we document the formal voting registration process in India and provide preliminary insights—from prior research and qualitative fieldwork—illuminating the difficulties migrants encounter in this regard.

Voter Registration Process

India uses simple plurality rules to elect 543 Members of Parliament (MPs) to single-member districts. Each citizen in our sample is further represented by an elected Member of the Legislative Assembly (MLA, a state-level position) as well as an elected municipal corporator.

Our investigation was timed to coincide with the 2019 Indian national (MP) elections. Citizens are required to initiate the registration process, which can be done online or on paper. The process, which is mandated by the federal Election Commission of India and is the same nationally, has four components:

-

• Form-filling. Registrants must complete the “Application for Inclusion of Name in Electoral Roll” (Form 6, reproduced in Online Appendix C). Migrants must also annul their registration in their prior place of residence and submit the deletion slip (Form 7), or they must declare that they were not previously registered elsewhere.

-

• Documentation. Citizens must provide proof of local residence (for example, a locally addressed electric/gas bill, ration card, driver’s license, or bank passbook), passport size photographs, and proof of age (e.g., birth certificate). If the applicant is a tenant, her landlord is usually expected to sign an affidavit confirming current occupancy.

-

• Submission. Applications are submitted to the registration office of the Assembly Constituency in which the citizen resides. Alternatively, applicants can hand over the documents to a Booth Level Officer (BLO) during brief voter registration drives conducted annually by local election offices.

-

• Verification. Local voter registration offices process the forms. If in order, a BLO will then pay an in-person visit to the applicant’s given address to verify that the submitted photograph matches the applicant. A voter identification card is mailed by post to the applicant following approval, and their name is entered on the local voter roll. Rejections occur either when documents are judged incomplete or improperly filled or when the applicant is not found during the BLO’s visit.

Barriers to Registration

Inertia, corruption, and classism mar India’s voter registration system. Peisakhin (Reference Peisakhin2012) found the median processing time for new voter registrations to be 331 days for slum residents in Delhi. To maximize rents, “officials at election registration offices did almost everything in their power to indirectly encourage applicants … to turn to middlemen for assistance” (Peisakhin Reference Peisakhin2012, 139). Nonbribe payers were additionally harassed, being asked to supply documents not required by law.

Our own interviews back these claims, while also highlighting the peculiar problems migrants face in registering to vote.Footnote 17 The BLOs betrayed animus toward migrants in interviews, referring to them as “troublemakers.” According to one officer:

Petty crimes in the area have shot up since the recent influx of migrants. They use voter IDs to get loans and then abscond. I would perform numerous background checks on a prospective tenant who is a migrant since all his ID proofs will carry my address, and it is me who stands to get bogged down by all the police paperwork in the event of an untoward incident. At the voter office, we are advised to exercise caution in our dealings with migrants.Footnote 18

Local elites were skeptical about migrants’ motives for registering. “It wouldn’t be a stretch to say that in the case of migrants, the primary motive for obtaining voter IDs is not the right to vote itself;” rather, they care only about the “potential benefits,” including a “claim to a government plot” if the slum is demolished, as well as “healthcare and education benefits.”Footnote 19 Pradhans (local community leaders) flagged landlords’ apprehensions about migrants obtaining local voter ID cards:

Landlords frequently refuse to sign the mandatory undertaking required by a tenant while filling registration Form 6. Further, landlords have, in the past, dragged the election office to court for registering migrants without their approval. Subsequently, BLOs have been as wary as the landlords themselves in dealing with tenants in bastis [slum colonies].Footnote 20

Migrants harshly criticized the election management system. “The voter office is jolted out of its inactivity only days before the elections. I suspect bastis are not even a priority for them. This year BLOs arrived at Ambedkar Camp … clueless and ill-prepared.”Footnote 21 According to another, “A few years ago, I had approached the Election Officer at the Dwarka voter registration office only to be told that the concerned BLO had resigned and there was nobody assigned to our basti at the moment.”Footnote 22 These accounts testify to migrants’ predicaments in registering to vote in destination cities.

Indian parties have, at times, engaged in voter registration drives to bring on board new supporters. Yet parties’ record of migrant outreach is patchier. Registration costs are high for parties because Indian electoral law requires that registration applications be filed before candidate nominations are declared, at a time when party organizations are typically shuttered. Knowing whether and in what way migrants will vote is challenging: India is multiethnic and multilingual; it has sprawling migrant-dominant slum settlements, and voters and candidates routinely switch parties. Online Appendix D analyzes representative data from the 2015 Delhi state assembly elections showing that recent internal migrants were 13.6 percentage points less likely to have been targeted for voter outreach by the city’s political parties compared with Delhi’s long-term residents. Overall, India’s urban migrants evince low rates of registration under the status quo. Parties’ engagement with migrants appears to fall short of their engagement with local-born residents.

Research Design

We implemented a large, multilevel field experiment to shed light on the reasons why migrants often do not incorporate politically into destination cities and the degree to which such disengagement is remediable.

Sampling, Recruitment, and Baseline Survey

Sampling and the administration of the baseline survey proceeded in four stages.

-

1. Site selection. We first generated a list of 150 migrant-dominated settlements, which is to our knowledge the most comprehensive list of such settlements for Delhi and Lucknow. To make this initial frame of potential sites, we relied on census data, schedules of informal settlements produced by city governments, and information gleaned from respondents at migrant-dominated labor chawks (markets). Scoping teams of 30 researchers assessed the suitability of potential sites over a period of nine months. During visits to settlements, they surveyed residents regarding the possession of local voter ID cards. The study includes those settlements where informants reported the greatest numbers of unregistered internal migrants residing.

-

2. Individual-level screening. Within selected neighborhoods, enumerators employed interval sampling to choose potential households to interview. Informed consent was requested from the adult household respondent with the next upcoming birthday. Therefore, only one subject was sampled per household. Subjects stating that they neither were born in the city nor had a voter ID card enabling them to vote there were deemed eligible. Thus our full sample is intended to be representative of unregistered migrants in sampled colonies.

-

3. Short baseline on omnibus sample. Eligible subjects were asked about basic demographics; their past voting behavior; and the extent of their social, economic, and political connections to their home villages or towns. At the conclusion of this module, we asked whether they wished to obtain a local voter ID card. The survey ended if a respondent replied “no.” These initial questions, as well as the overall take-up rate, are used to test the plausibility of the voluntary detachment hypothesis.

-

4. Long baseline on experimental sample. Respondents replying “yes” entered the experimental sample. We posed a larger set of demographic and attitudinal questions to this group. Descriptive statistics are provided in Supplementary Information F. These subjects were then randomized into different treatment conditions.Footnote 23

Representativeness

In Online Appendix B, we benchmark our experimental sample against nationally representative survey data collected in the second round of the Indian Human Development Survey (IHDS-II). Comparing household characteristics in IHDS-II by migrant/nonmigrant status in both rural and urban areas, we highlight three key respects in which our sample generalizes. First, migrants overall evidence lower political participation rates than nonmigrants. Second, marginalized caste groups and the poor are overrepresented both in our sample and in the wider internal migrant population. A third point of note concerns connectivity to patronage networks. Conceivably, our sampling criteria, which hinge on migrants’ stated willingness to register, select for migrants who are comparatively excluded from clientelistic channels in home regions. In fact, the IHDS-II benchmark demonstrates that rural migrant-sending households are less enmeshed in client–patron relationships than were others, potentially spurring migrants’ decision to “move to opportunity” to begin with.Footnote 24

Treatment 1: Individual-Level Registration Drive (Migrant-Targeted)

Our primary intervention (“T1”) operated at the level of individual migrants. Its purpose is to test our second hypothesis regarding bureaucratic hassle costs. Simple randomization was used to assign individuals who completed the long baseline survey to T1 with 50% probability. Remaining subjects were assigned to a pure control condition.

The intervention was an intensive door-to-door facilitation campaign to help migrants obtain a local voter identification card (see Online Appendix C for further details). This card would enable them to participate in the forthcoming national elections in the city where they were living (either Delhi or Lucknow). To begin, a worker trained with the help of our NGO partner visited migrants at their place of residence and presented their credentials. The worker described the benefits of holding a local voter ID card, the process for getting one, and the type of assistance the worker could provide. The worker asked whether the migrant had the necessary supporting documents at hand.Footnote 25 If they did, the migrant was asked to gather those documents in time for a future visit and a time was set. Migrants who lacked these documents were instructed on how to get them.

At the follow-up visit, the worker helped the migrant to complete the required forms online using an internet-enabled computer tablet. At the end of the meeting, workers ensured that the form, along with uploaded photographs of the required documents, were submitted to the local registration office. The worker then tracked the progress of the applications. Where problems arose—often, for example, BLOs were unable to track down the applicant at their listed residence—the worker intervened to try to fix the issue.

Treatment 2: Cluster-Level Information Dissemination Campaign (Politician-Targeted)

Our second treatment arm—henceforth, “T2”—operated at a cluster level and was intended to help adjudicate the plausibility of our third theoretical claim concerning politician ostracism. Using GIS software and publicly available information on the locations of polling stations in Delhi and Lucknow, we identified the 87 polling stations in closest proximity to our geo-located sample of experimental subjects. Each subject was tagged to the nearest one of these polling stations. We then divided the 87 polling stations into four blocks, defined by city and whether the number of experimental subjects assigned to that polling station was above or below the city’s median number of experimental subjects per polling station. Last, we randomly assigned polling stations within each randomization block to either the T2 intervention or to the T2 control condition. Randomization to T2 was thus fully independent of the T1 trial.

Between two and four weeks before election day—during India’s month-long campaign season and following parties’ selection of candidates—we sent individually tailored letters, WhatsApp messages, and emails to four types of politicians tied to each polling booth: the incumbent MP, officially declared MP candidates, incumbent MLAs, and incumbent municipal corporators. Politicians’ contact details were gleaned from public databases. The messages were written in both English and Hindi. They informed the politicians that a voter registration drive had been recently carried out among internal migrant communities in their area (see Online Appendix E for examples of the communications).Footnote 26 The purpose of the treatment was to disseminate information about the registration drives that had taken place and thus to positively update politicians’ beliefs about the average registration rate of migrants in those localities.

Outcomes

Outcomes were measured in an endline survey conducted approximately two months after the elections were held. The study timeline is shown in Online Appendix F, and the survey question wordings are given in Supplementary Information G. Methods used to create indexed outcomes are described in Online Appendix G.

Analysis

For estimations involving T1, we run ordinary least squares regressions of the following form:

where, i indexes subjects, Y is the dependent variable of interest, T1 is a dummy taking 1 if the subject was assigned to the registration facilitation campaign and 0 if assigned to control, u is the error term, and X is a vector of baseline covariates, included to improve statistical precision. All specifications control for gender, age, religion, caste, education, income, marital status, length of residence in the city, and homeownership status.Footnote 27 Where specified, we also included pretreatment measures of outcomes. T1 analyses use Huber–White robust standard errors.

For the T2 analysis, we employ weighted least squares regression:

Here, Y is the outcome of interest, T2 is a binary indicator taking 1 if individual i in cluster j was assigned to the T2 treatment and 0 if assigned to T2 control, and X is a vector of controls—the same set used for the T1 estimation—and δs are block fixed effects. We use cluster-robust standard errors, clustering at the polling booth level, which is the unit of randomization. As was prespecified, we reweight individuals such that each cluster contributes equally to the estimation.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) effect is the quantity of interest across all experimental analyses. In tests of balance and attrition we statistically find no threats to internal validity (see Online Appendix I). We successfully reinterviewed 91% of baseline subjects at endline. Our study was preregistered at the Evidence in Governance and Politics registry (#20191007AA).Footnote 28

Ethics

Our experimental design was informed by ethical best practices. To begin, we selected a sample size that was no larger than we deemed necessary to detect meaningfully sized treatment effects. Further, the sites in which we worked were not electorally competitive—the national ruling party secured strong victories across all study constituencies in the preceding election and in the election we investigated—implying that there was a negligible risk of affecting aggregate electoral outcomes.

Next, our nonpartisan intervention partner had already conducted extensive voter registration campaigns among urban migrants. It is a not-for-profit organization working in the fields of slum rehabilitation, housing rights for migrant workers, and slum sanitation and public health. Public advocacy for migrants has been at the core of its activities, meaning that such drives—conducted both by our partner and other civil society organizations—would have occurred in our absence.Footnote 29 This was a multistakeholder project. As academic partners, our role was to scientifically evaluate the efficacy of the NGO’s efforts in helping empower migrants to take up their constitutional rights to participate politically in destination cities.

Regarding context, we relied on the community-level embeddedness of our partner organization and field team (a) to be confident ex ante that the intervention was contextually and culturally appropriate; (b) to ensure that the registration intervention, as well as common knowledge of it, would not invite pushback—based on our partner’s relationships with local elites and past experience running and publicizing such campaigns; and (c) to have in place a set of protocols capable of providing immediate feedback on potential unanticipated events on the ground. In addition, we sought the permission of the Election Commission of India as well as community leaders in each slum colony prior to beginning work there.Footnote 30 We further vetted the design with Delhi- and Lucknow-based NGOs and academics not involved in the study.

The costs to study participants were quite minimal: the voluntary completion of two surveys and the time required to initiate registration if the subject so wished. There were several likely benefits. Directly, subjects receiving the registration intervention were able to exercise suffrage locally. Our prior research provided a strong basis for believing that political incorporation would yield material benefits for newly enfranchised urban migrants in the form of increased supply of essential constituency services by local politicians (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2021a).Footnote 31 Apart from gains to study participants themselves, there was (and remains) a pressing need to learn what works to raise turnout among hitherto politically marginalized groups. The unique incorporation challenges facing internal migrants in fast-urbanizing democracies have largely eluded attention, even as this population balloons in size. Our study helps establish an evidence base for policy initiatives that can be deployed by governments and NGOs working in this space.Footnote 32

Results

What causes migrants’ political exclusion? Turning to our data, we first characterize the sample. Subjects’ average age was 29; 54% were female, and 65% had attended primary school. Also, 77% of respondents had relocated to the city from villages, 8% from towns, and the remainder from other small or large cities. We asked the profession of the main working member of each interviewed household. Most household heads were said to be engaged in unskilled/semiskilled (33%) or skilled (26%) production, followed by commerce (16%). Subjects had spent 11 of the past 12 months residing in host cities, on average.Footnote 33

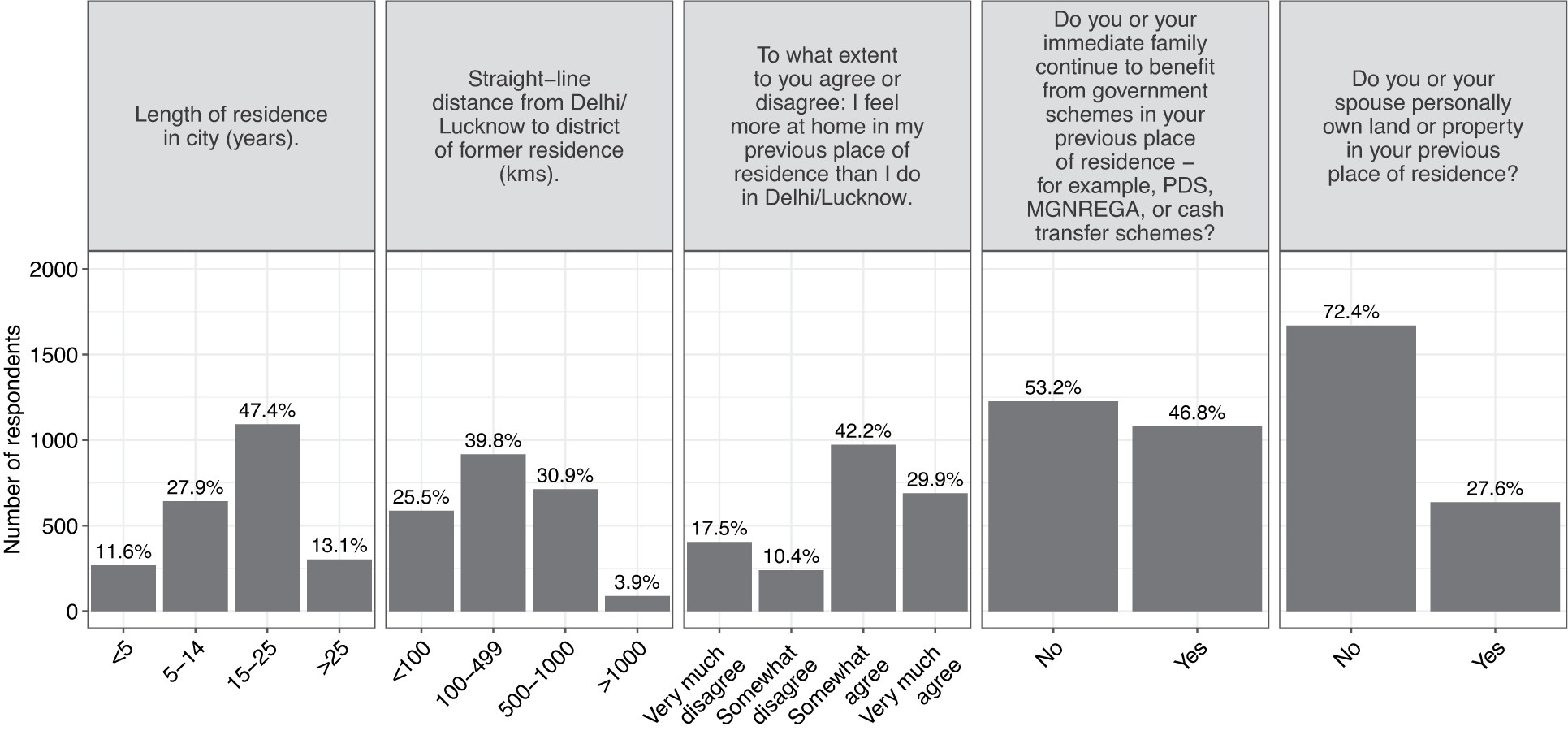

Voluntary Detachment

Recall, our first hypothesis zeroed in on socioeconomic ties to home regions as an explanation for political nonincorporation. Baseline data, plotted in Figure 1, underscore the prima facie plausibility of these claims. Subjects retained strong linkages to their hometowns. Socially, a large majority (72%) weakly or strongly agreed that they felt “more at home” in their previous place of residence—suggesting the possibility that they continue to feel alienated in their destination cities. This was true even though 75% of migrants lived more than 100kms away from their home district and 35% lived more than 500kms away, making regular visits impractical. A significant minority had material stakes in origin areas: 28% personally owned land or property and 47% reported benefiting from government schemes there. Simply put, migrants in our sample proved highly attached to their origin regions.

Figure 1. Baseline Descriptive Statistics of Migrants’ Attachments to Their Former Places of Residence

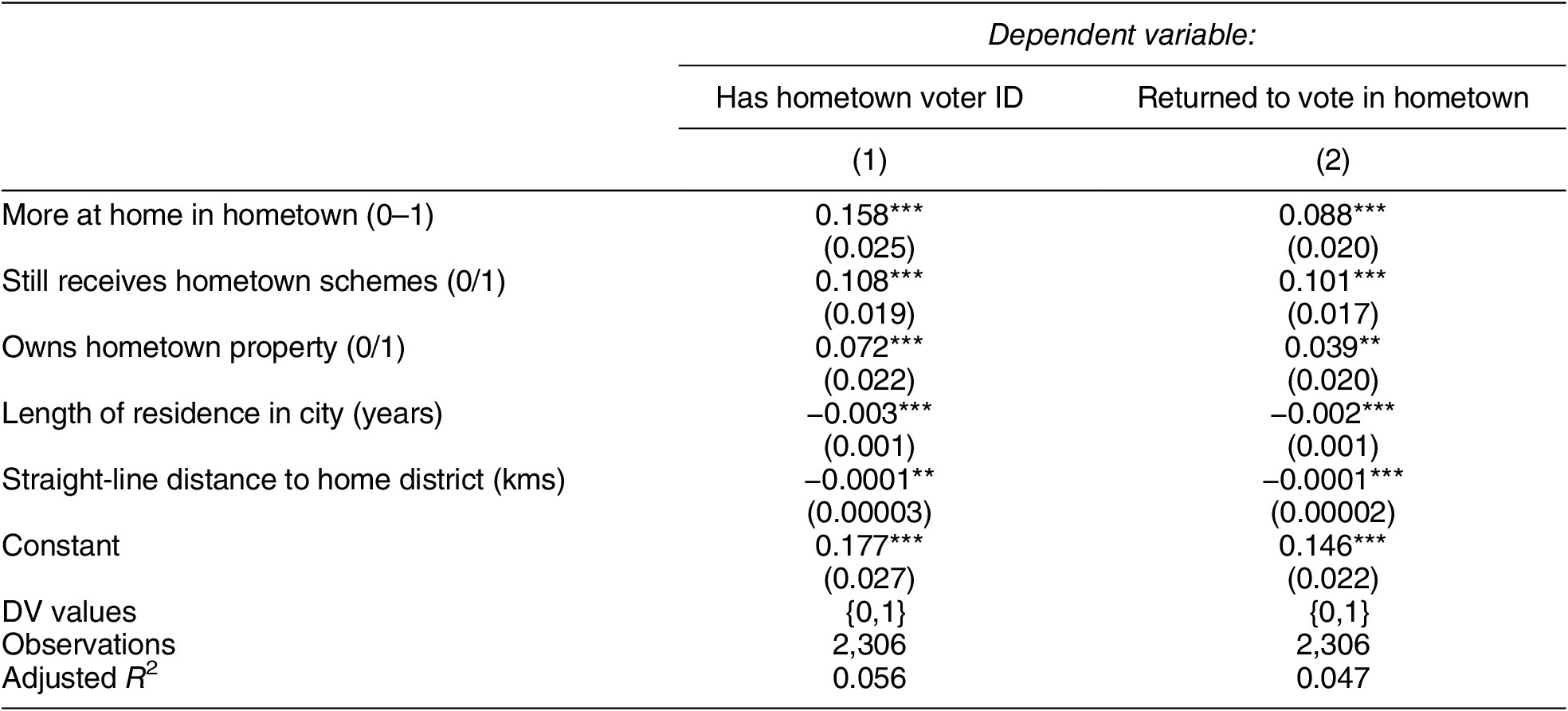

Under the theory of voluntaristic detachment, such socioeconomic bonds to “home” should predict ongoing political participation there. To investigate this, we regress indicators for (a) whether the migrant possessed an origin-area voter ID card and (b) whether they had previously left the city to vote in their hometown on the socioeconomic characteristics just described as well as one extra migrant attribute. The results are displayed in Table 1. Greater subjective attachment to origin regions, current receipt of government schemes, and owning hometown property all emerge as robust, positive correlates of origin-area political engagement postmigration. Longer-term residence in the city and greater geographic distance to home are negatively associated with those outcomes.

Table 1. [Exploratory] Baseline Correlates of Migrants’ Continued Political Participation in Their Former Place of Residence (“Hometown”)

Note: Estimated using OLS regression. For question wordings, see Figure 1. Robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

On first inspection, the patterns highlighted in Table 1 suggest that persistent socioeconomic attachments to home may induce migrants to hold onto origin-area engagement, as theories of social-group pressure, economic interests, and clientelism imply. However, we now proceed to examine our formal test of the extent to which these factors depress demand for political incorporation among migrants. At the end of the short baseline survey that was fielded on the omnibus sample (intended to be representative of city-based unregistered migrants), we asked eligible migrants whether they were interested in taking steps to register to vote locally—the main eligibility criterion for entering the experimental sample. Of the 2,350 subjects in the omnibus sample, an overwhelming majority—98%—replied “yes.” In other words, notwithstanding their material and social connections to hometowns, almost all favored concentrating their political activities in destination areas. We infer that such factors are not sufficiently potent in and of themselves to reduce migrants’ willingness to incorporate politically into the city. There is, then, sizable pent-up demand for incorporation.

While perhaps surprising in light of Figure 1, migrants’ stated desire to integrate politically sits with their positive estimations of their economic situation in the city. A majority—65% of respondents—rated their current employment opportunities as “good” or “very good,” something that only 23% said of their opportunities in their place of origin at the time they left. Only 3% stated that their incomes had gotten worse since migrating, whereas the rest claimed their incomes had stayed the same (26%) or gotten better (71%). Consistently, 96% of subjects expressed an intent to reside in their destination cities permanently. At the same time, many subjects reported a low sense of political efficacy. We asked to what extent they agreed that “people like me don’t have any influence on the government in [Delhi/Lucknow].” Forty-seven percent agreed. It appears, then, that city-based political incorporation is seen as desirable—if not essential—by a population that has come to be economically and residentially ingrained in the city, even as individuals continue to maintain links elsewhere.

Bureaucratic Hassle Costs

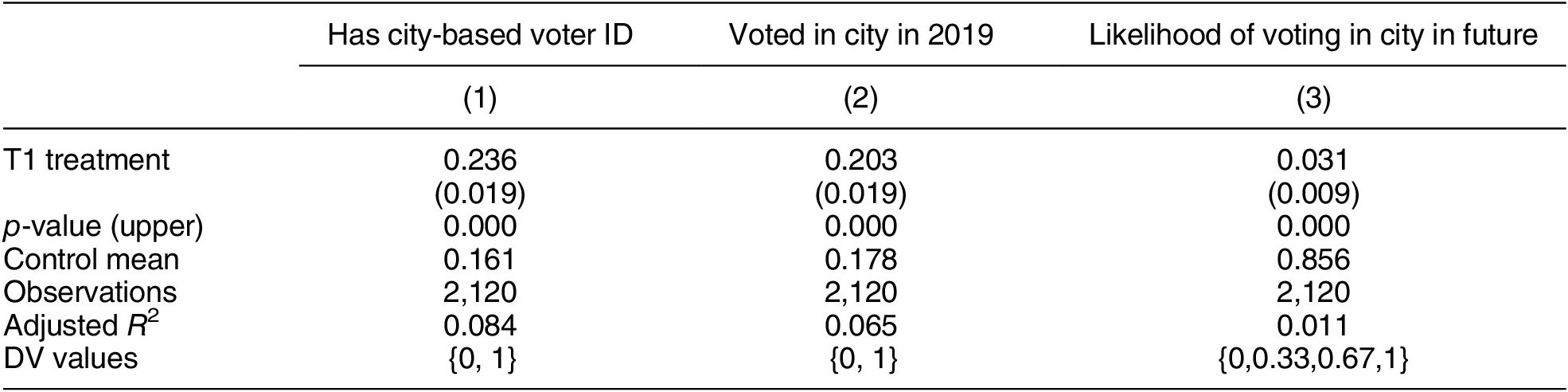

Voluntary detachment is inadequate to account for the low rates of voting and political participation among internal migrants in the Indian cities we study. We thus turn to our second candidate explanation for migrant exclusion—onerous voter registration procedures—which we test using our T1 experimental manipulation.

Table 2 presents the key T1 experimental results for our primary political outcomes. Column 1 shows that the intervention had a sizable first-stage effect. Note, only migrants lacking locally valid voter ID cards at baseline were eligible to participate in the study. By endline, 16% of control group subjects had gone on to obtain a local voter registration document. According to our main specification (Table 2, column 1), providing simple assistance with this procedure boosted registration rates by 24 percentage points, over and above the control group mean. This equates to a 147% proportional increase. The estimated effect is substantively large and statistically significant (p < 0.001), supplying strong evidence that the real or perceived costs of local voter registration prevent large swathes of India’s migrants from appearing on city voter rolls.Footnote 34 Providing simple at-home assistance can go a long way toward remedying migrants’ deficient representation in urban electorates.

Table 2. [Pre-Registered] T1 Experimental Results For Primary Political Outcomes

Note: Outcomes are whether respondent (1) currently has a voter ID card allowing them to vote in city elections, (2) voted in the city during the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, and (3) intends to vote in the next state elections held in the city. OLS estimates of intent to treat effects. Models include covariates. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

The right-hand columns of Table 2 quantify effects for turnout: whether subjects voted locally in India’s 2019 national election and their assessments of how likely they were to vote in future subnational elections. Assignment to the registration campaign increased the probability of turning out to vote by 20 percentage points (p < 0.001), totaling a 114% increase relative to the control group average (Table 2, column 2).Footnote 35 These are large effects. Benchmarking them against theoretically established drivers of participation, we note that Panda (Reference Panda2019) finds each additional year of education is associated with a 2.4-percentage-point reduction in the probability of voting in Indian national elections, while below-the-poverty-line status corresponds to a 3.2-percentage-point increase in turnout likelihood. The effect of our bureaucratic-assistance intervention outstrips these associations in magnitude. The intervention also caused subjects to state that they would be more likely to vote in the city’s next state election (Table 2, column 3). This hints at the potential for a longer-term effect—persistence that might also be engendered by the habit-forming effects of first-time participation in city elections (cf. Meredith Reference Meredith2009).

We next examine how the treatment shaped subjects’ political consciousness. To begin, we combine two measures of political interest—one capturing attention to city politics and the other to national politics—to generate a Z-score index. The results for the overall “Interest” outcome are shown in Table 3, column 1. Assignment to the intervention caused a 0.091-standard-deviation increase in political interest (p = 0.010).Footnote 36 Our survey asked respondents the extent to which they agreed that politicians are accountable to citizens. The control group average for this ordinal variable suggests that most citizens “somewhat agree” that politicians are accountable (Table 3, column 2). We find that assignment to treatment raised perceptions of accountability by four percentage points (p = 0.003). Possessing the documentation needed to vote thus enhanced citizens’ beliefs that good types of politicians can be rewarded at the ballot box and bad types punished.

Table 3. [Pre-Registered] T1 Experimental Results for Additional Political Outcomes

Note: Outcomes are whether respondent (1) pays attention to news about national, state, and city politics; (2) agrees that elected politicians are accountable to city residents; (3) agrees that citizens have an influence on the government; and (4) has trust in the national, state, and city governments, as well as political parties. OLS estimates of intent to treat effects. Models include covariates. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

By contrast, we do not observe any increase in citizens’ sense of political efficacy (Table 3, column 3) or of political trust, measured as an index that combines trust in national, state, and municipal governments as well as political parties (Table 3, column 4). It may be that these null estimated effects reflect the reality that, while voting raises awareness that politicians are vulnerable to being ousted (accountability), it does not change certain fundamentals: that an individual citizen has limited sway over the government of a vast polity (efficacy) and that core democratic institutions will not immediately be transformed by an additional migrant registering to vote (trust).Footnote 37

We have thus far presented the main effects of our T1 experimental intervention. An important question is whether the campaign worked symmetrically across different classes of migrants or whether it affected migrant subgroups differentially. We test five moderators, all but one of which focus on salient dimensions of social and economic marginalization in the Indian setting:

-

• Muslims, who comprise 14% of the country’s population and 24% of our study sample, have historically been targets of discrimination and violence (Gaikwad and Nellis Reference Gaikwad and Nellis2017).

-

• Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) are on the lowest rungs of India’s rigid caste hierarchy. Social bias against these groups is widespread. Combined, SCs and STs make up 38% of the sample, surpassing their share of the national population (25%).

-

• While India enshrines the right to primary education in its constitution, in practice many citizens do not receive even basic schooling; 35% of respondents in our sample had not attended primary school.

-

• We partition subjects at the sample median of monthly household income. At INR 10,000 (USD 131), this number is low, highlighting the poverty of many urban migrants.

-

• Last, we look for differential effects by whether the respondent is a long-term migrant—that is, whether their number of years in the city exceeds the sample median value.Footnote 38

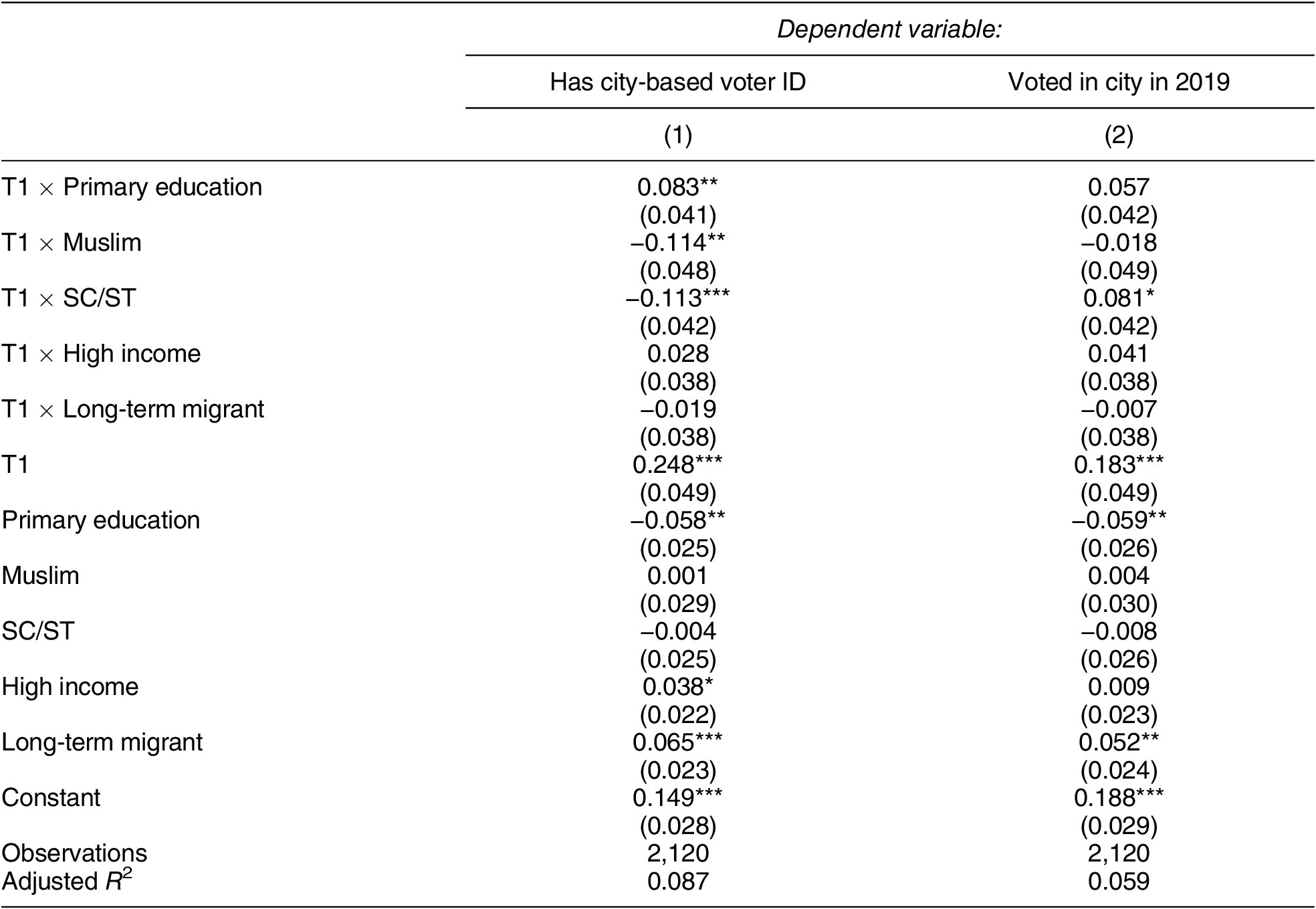

Table 4 displays our two sets of preregistered tests of heterogeneity for the two primary political outcomes: receipt of a local voter ID card and city-based voting in the 2019 election. The interaction coefficients are interpretable as the differences in T1’s effect across the groups defined by each dichotomous moderator. The estimates in column 1 paint a consistent picture. In terms of first-stage effects, the intervention proved more effective for relatively advantaged migrant subpopulations. Controlling for migrants’ other background characteristics and their interactions with the treatment, we find that the effect of the intervention was 8 percentage points larger for those with primary education (SE = 0.041). The gulf in treatment efficacy is wider still for Muslims and SCs/STs. The estimated effect of the intervention was 11 percentage points lower for Muslim migrants than for non-Muslims (SE = 0.048). Likewise, the effect of T1 on SCs/STs is 11 percentage points lower than it was for non-SCs/STs (SE = 0.042). That said, the heterogeneous effects for turnout in column 2 are substantially smaller and only statistically significant for the SC/ST moderator.

Table 4. [Pre-registered] Estimates of Heterogeneous Effects of T1 Treatment

Note: Models do not include additional covariates. All independent variables are dichotomous and are described in the text. Robust standard errors in parentheses.*p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

A fuller explanation for the variability in treatment effects on registration awaits future research. Yet our interviews with local brokers and community representatives in several sampled slum colonies indicate that the actions of local electoral gatekeepers may form part of the story.Footnote 39 A common refrain heard was that minorities, when made to establish their credentials, were held to a double standard:

Muslim migrants from West Bengal must constantly deal with persecution owing to the authorities’ suspicion of them being Bangladeshi. This may have been aggravated due to the government’s NRC [National Register of Citizens] policy.Footnote 40

A second interviewee stressed that “[t]here is wide variation in documentation requirements for forward castes vis-à-vis minorities [Muslims and SCs/STs]. In case of the former, verbal confirmation often suffices, while the latter are subjected to onerous formalities.”Footnote 41 The extra burden placed on minorities may be a product of individual-level discrimination by officials, or it may represent more systemic discrimination. As one respondent commented, “BLOs and AEROs [Assistant Electoral Registration Officers] are very risk averse professionally. They are doubly apprehensive and place more stringent documentation requirements on Muslim migrants relative to other demographics, fearing reprimand from senior officials.”Footnote 42

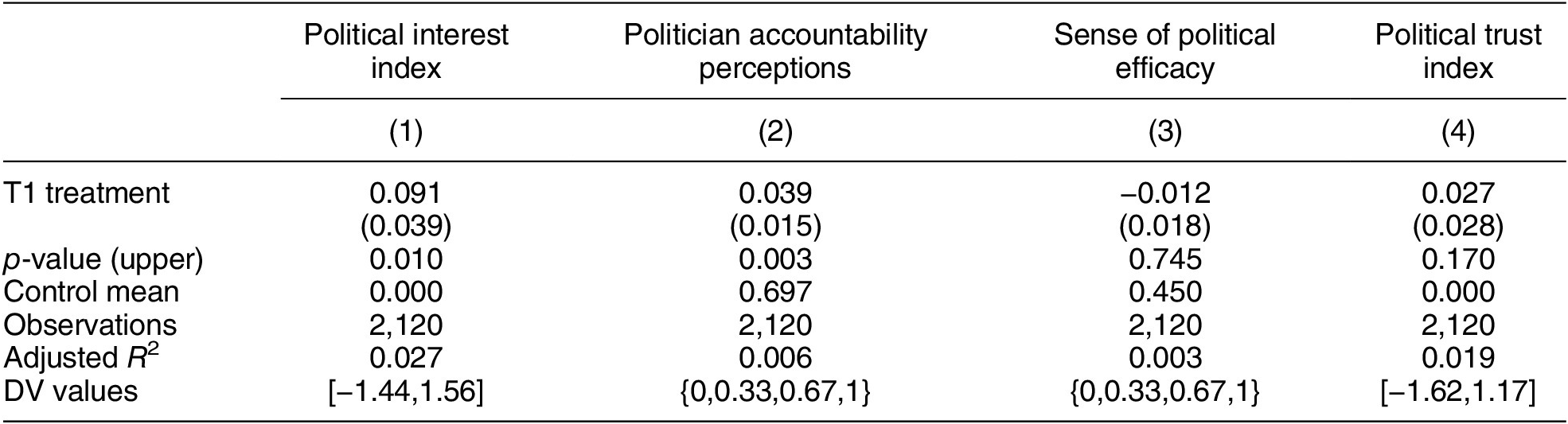

Ostracism by Political Elites

We have shown that subsidizing the costs of voter registration fosters migrants’ engagement in urban politics. Thus, there is considerable evidence that bureaucratic hurdles forestall migrant registration. We now adjudicate our final theoretical explanation for migrants’ political exclusion: ostracizing behavior on the part of political elites. Put simply, if elected elites on the “supply side” of politics resist or ignore even registered migrants, then migrants might reasonably find it unprofitable to situate their political participation in cities in the first place—or will see little reason to go on investing time and effort into city-based participation going forward.

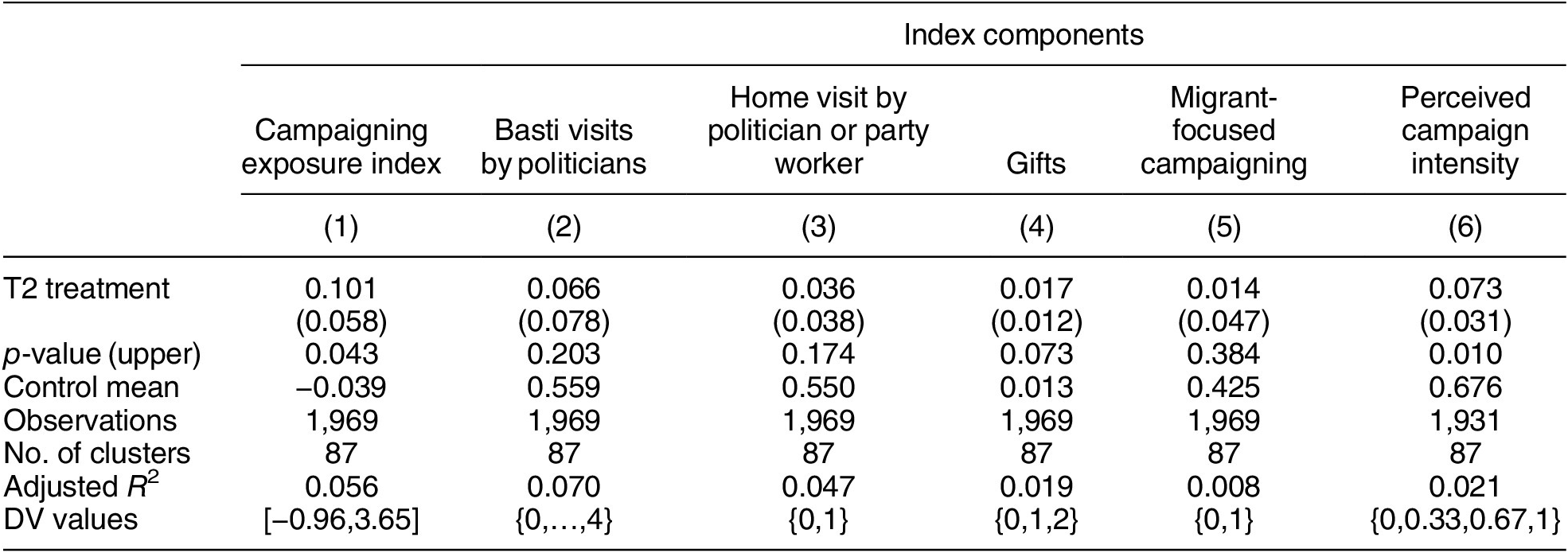

To assess whether such exclusionary behavior by politicians occurs, we exploit our T2 clustered experimental design, examining five endline variables that measure exposure to the 2019 Lok Sabha campaign as well as the Z-score index that combines them.Footnote 43 The raw responses indicate the campaign was quite hard-fought. A total of 79% of subjects either strongly or somewhat agreed that politicians and party workers had campaigned hard to win votes in the respondent’s neighborhood, 40% said that at least one incumbent politician or MP candidate had visited their basti, and 2% reported having been offered a gift.

Did informing local politicians about the rollout of a migrant-focused voter registration drive in the vicinity of a polling booth cause them to direct additional campaign resources there, or were such new voters disregarded? The evidence in Table 5 argues strongly for the first possibility. Looking at the preregistered analysis on the campaign exposure index (column 1), we see that respondents living near polling booths assigned to the T2 information dissemination condition report campaign exposure 0.10 standard deviations higher than subjects close to polling booths that came under the control condition (p = 0.043). Columns 2–6 break down the results for each component measure. This exercise reveals that the positive effect on the overall index comes primarily from the increase in perceived campaign intensity (column 6) and, secondarily, from a rise in the number of gifts offered to treated migrants (column 4). This second result is telling. It suggests that the campaigning windfall felt by subjects was “pro-migrant” and not due to politicians ramping up pro-local rhetoric in areas with a burgeoning migrant electorate.Footnote 44 We do not see movement on three of the other index components: basti or doorstep visits by politicians or on migrant-focused campaign activities. In seeking to expand their electoral reach, it seems, city-based politicians were not tailoring their campaigns in ways that might be off-putting to local-born residents—broadcasting, say, messaging in which migrant themes feature prominently. Rather, without noticeably modifying the content of their campaigns, politicians appear to have increased the quantity of campaigning where they knew there to be more migrant voters.

Table 5. [Index Outcome Pre-Registered; Index Component Analyses Exploratory] T2 Experimental Results for Exposure to Campaigning during the 2019 Lok Sabha Elections

Note: Campaign exposure index (1) based on whether respondent reports that politicians or party workers (2) visited their basti around the 2019 Lok Sabha election campaign, (3) came to the door to request votes, (4) offered gifts, (5) tried to specifically win votes of recent migrants to the city, and (6) campaigned hard to win votes in the basti. Weighted least squares estimates of intent to treat effects. Clusters weighted equally. Models include block fixed effects and individual covariates. Cluster-robust standard errors in parentheses.

The fact that urban politicians bolstered campaigning in response to information about migrant-focused voter enrollments is encouraging, pointing to a state of the world in which migrants register to vote and politicians incorporate them more fully into the mainstream political life of the city. It further indicates that localist bias and neglect by urban politicians is unlikely to be a principal explanation for migrants’ low registration rates in city elections.

We earlier described the reasons why parties may be hesitant to involve themselves in the business of registering migrants to vote: the unit costs are high and migrants’ propensity to vote, as well as their ultimate vote choice, are clouded with uncertainty. The analysis in Table 5 clarifies that once the costs of migrant registration have been carried by other actors, office-seeking politicians and party machines treat migrant voters conventionally: plying them with selective benefits and rallying their support.Footnote 45

Conclusion

We offer new theory and evidence to explain the drivers of migrants’ low rates of political incorporation into destination regions. A large, multisite experiment in India identifies bureaucratic hassle costs rather than migrants’ voluntary abstention from urban politics or political ostracism as the salient constraint. Subsidizing these costs by providing at-home assistance in registering to vote substantially increases political incorporation: raising registration rates, turnout, political interest, and perceptions of political accountability. Moreover, political elites react to news of the local enfranchisement of migrants by boosting electioneering in the vicinity.

The experimental evidence we adduce comes from two major cities that are jointly home to 22 million people (roughly the population of Scandinavia). The substantive findings, along with the theoretical framework that motivates them, have broad scope for generalizability. For example, a report by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (Mooney and Jarrah Reference Mooney and Jarrah2004, iii) notes that internally displaced persons “face obstacles in exercising their right to vote, sharply reducing their influence over the many political, economic and social decisions affecting their lives.” To be sure, the dominant factor for explaining political exclusion—whether voluntary detachment, bureaucratic impediments, or ostracism by local elites—may vary contextually.Footnote 46 For instance, in settings where highly pronounced cultural differences exist between migrants and nonmigrants, voluntary detachment may emerge more prominently as a cause of nonincorporation. Still, onerous voter-initiated registration systems, which our study distinguishes, are the rule rather than the exception in the world’s largest low- and middle-income democracies. This suggests that the mechanisms we decode likely operate elsewhere.

Policywise, the findings are relevant for election management bodies in states witnessing explosive urban growth. Rejecting proxy voting for internal migrants as logistically unfeasible, a recent review by the Election Commission of India recommended instead that migrants reregister in their new locations, employing the existing voter-initiated procedure.Footnote 47 As we document, this may underestimate the multiplex and unusual challenges that migrants confront in navigating such systems. Building capacity to streamline and perhaps automate registration should be a priority for the future.

There are also lessons for migrant advocacy groups. Investing in voter registration drives is worthwhile in territories where citizens are mobile. Our results sound a note of caution, however. The registration facilitation outreach, while effective overall, had a more positive influence among migrants belonging to advantaged ethnic, religious, and educational subgroups. These lopsided benefits highlight a trade-off. Easing registration requirements can lift the share of migrants in urban electorates but worsens representativeness along other axes of social identification. It will be important to engineer interventions that avoid producing such political inequalities.

The effects of political incorporation on social and economic integration merit investigation. Inter alia, future research should explore whether registration causes migrants to be more likely to consider cities home, to forge social ties with locals, and to be more willing to pay for city-based public goods. These issues have come to the fore during the COVID-19 pandemic, when the needs of millions of India’s migrants went untended by political elites and local populations (Rajan, Sivakumar, and Srinivasan Reference Rajan, Sivakumar and Srinivasan2020).

We end by underlining how the paper’s findings matter not only for within-country migrants. Low registration rates also characterize immigrant-background groups (Alizade, Dancygier, and Ditlmann Reference Alizade, Dancygier and ForthcomingForthcoming). Bass and Casper (Reference Bass and Casper2001, 105) write of “naturalization and registration” as “the first two barriers to voting” for foreign-born residents in the United States, where interventions like the ones evaluated here have recently become a mainstay of activist efforts to incorporate immigrant communities.Footnote 48 Our evidence suggests that high-intensity campaigns of this sort can facilitate political incorporation and incentivize parties and politicians to bring these communities into their electoral coalitions. Thereby, political exclusion may be overcome.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000435.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/G1JCKK.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to the Institute of Social and Economic Research and Policy at Columbia University and the University of California, San Diego for funding; to MORSEL PLC for fieldwork; and to our NGO partner for their assistance with the intervention. For comments and advice, our thanks to Claire Adida, Allison Carnegie, Richard Clark, Jasper Cooper, Fabien Cottier, Thad Dunning, Susan Hyde, Hyeran Jo, Kimuli Kasara, Mayya Komisarchik, John Marshall, Carlo Prato, Kenneth Scheve, Jack Snyder, Michael Weaver, and workshop participants at Columbia University, the University of California, San Diego, the University of Rochester, the 2019 Conference on South Asia at Madison, the 2020 International Political Economy Society Annual Conference, the 2020 Global Research in International Political Economy Webinar, and Pia Raffler’s replication seminar at Harvard University. For outstanding research assistance, we are indebted to Heba Abbas, Thomas Brailey, Aaron Christenson, Aura Gonzalez, Karminder Malhotra, Bidisha Mandal, Rochan Mathur, Amritanshu Patnaik, Seungyup Sin, Nitin Teotia, and Shane Xuan.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the University of California, San Diego, and Columbia University.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors declare that the human subjects research in this article was reviewed and approved by the University of California, San Diego, Columbia University, and MORSEL Research and Development, and certificate numbers are provided in the text. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.