The final report of the World Health Organization's (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH), Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on the social determinants of health, was published in August 2008 (CSDH, 2008; Marmot et al., Reference Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling and Taylor2008). Welcoming the document on behalf of WHO, Director-General Margaret Chan noted: “the Commission's main finding is straightforward: the conditions in which people are born, live, and work are the single most important determinant of good health, or ill health; of a long and productive life, or a short and miserable one” (Chan, Reference Chan2008). The report presents an excellent overview and analysis of the range of structural factors that influence individual and population health, and makes a number of practical recommendations that seek to ensure that avoidable health inequalities are levelled out, so that everyone has an equal opportunity of leading a healthy life. Roughly around the time of publication of the CSDH report, and in the 60th anniversary year of the NHS, the UK Department of Health (DH) held a consultation on a draft NHS Constitution. The document aimed to set out the NHS’ fundamental values and principles and included a range of individual rights of NHS users, detailing also their responsibilities. A final version of the constitution was published in January 2009 (DH, 2009). Given the CSDH's emphasis on the primary role of the social determinants of health (CSDH, 2007, 2008), what should we make of the DH's initiative to introduce, for the first time in NHS history, explicit health-related responsibilities for individuals? Why talk about individual responsibility if yet further evidence has been produced that demonstrates the importance of environmental factors? For those sympathetic to the social determinants of health (SDH) approach, there seem to be three principal types of response: (i) to reject the DH's move; (ii) to agree that it makes some sense, but to argue that it should nonetheless be abandoned for other reasons; or (iii) to accept it as an approach that, in principle, is capable of complementing the aims of the SDH approach.

Regarding the first option, one could argue that the project of establishing individual responsibilities is simply misguided, as it assumes a degree of control by individuals over their health which they typically do not have. From this perspective, suggesting that individual action caused, or will cause, a certain health outcome is shortsighted, and what really matters is to acknowledge the role of the “causes of the causes” (CSDH, 2008). For example, one could point to the CSDH's discussion on obesity and argue that this example illustrates how talk about individual responsibility for health is generally meaningless. A great number of environmental factors, including access to healthy and affordable food and opportunities to exercise, determine whether or not people will be overweight or obese. Exploring the role of individual responsibility may be interesting in the counterfactual scenario where an environment has been created in which it is equally easy for all to achieve the right balance of energy intake and expenditure. But until such a state has been secured, any responsibility talk should be abandoned because it ignores the extent to which environmental factors determine what might seem like fully autonomous individual action. Moreover, responsibility talk also carries a significant risk of victimizing those who are already in the most disadvantaged positions, by blaming them for health outcomes that are largely beyond their control.

A second type of approach would be to agree that there can be “causes of causes”, but that this does not mean that individuals are absolved from any responsibility. From this perspective, it can make sense to think about the degree to which people might be able to exercise certain responsibilities. Using again the example of obesity, it might be argued that talking about a person's responsibility to maintain a healthy weight is of relatively limited use in the case of a single unemployed teenage mother who grew up and lives in a deprived inner city borough with a high density of fast food outlets, poorly maintained and unsafe parks, and no affordable sports facility and so on. But it might be more plausible in the case of someone who grew up and lives in a far more affluent part of the same town, and has enjoyed an environment and education that equipped her with the range of capabilities required for people to be self-motivated and efficacious. However, clearly, there is a range of cases between these two extremes. On practical grounds, it seems very difficult, if not impossible, to measure out and determine the exact scope of people's individual freedom and responsibility. Moreover, one might argue that even if it may occasionally be possible to make such assessments with certainty, or even if we accept some degree of fuzziness in ascribing responsibility, it is important to move away from such assessments on strategic grounds: they might distract the attention of policy makers away from addressing the underlying and hugely important social determinants of health.

Thirdly, one could agree with the second view that the first option builds on a too narrow conception of causality, but argue that both the first and second options also share too narrow a conception of responsibility. For both are preoccupied with linking the question of responsibility with proof that people have played a certain causal role, and moreover both assume that if we say that someone is responsible for something we also need to hold them responsible. I will explore below in what sense a more nuanced picture of responsibilities can make sense, and how such a view is capable of complementing the SDH approach. I will also suggest that there is nothing wrong in principle with the responsibilities that have been established in the NHS constitution, as long as a genuine both/and approach of individual and social responsibility is pursued in policy and practice.

Responsibilities in the NHS Constitution – types of responsibility

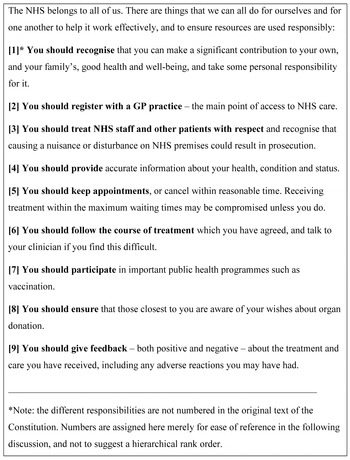

Figure 1 reproduces the responsibilities as included in the Constitution. Nine paragraphs set out obligations of healthy people and those who are sick, or recovering from sickness. The responsibilities fall in to three main categories: those directed towards oneself, towards others, and towards the health care system as a whole. For example, the obligations in the first, second, fourth and seventh paragraph are directed towards oneself in the sense that compliance is likely to be in one's self-interest as it leads to personal benefit. But the first paragraph also relates to obligations people have towards others: in referring to “your family” it asserts that one's actions have implications for the health of those to whom one may stand in a caring relationship, for example, children or parents. The third paragraph equally concerns health-related responsibilities towards others, by requesting respect for health care staff and other NHS users. Lastly, all responsibilities also specify obligations people have towards the NHS as a whole, as compliance is likely to ensure an efficient operation of the health care system and use of resources.

Figure 1. Excerpt from NHS draft Constitution – Section 2b on “Patients and the public – your responsibilities”

The first paragraph differs from the following in that it is somewhat more general than the remaining provisions. Presumably what is meant here is something like ‘lead a healthy life, take part in preventative and health maintenance activities, attend check-ups if you are in the relevant age and risk group, and play an active role in treatment and rehabilitation’. The supplement “and take some personal responsibility for it” is also somewhat unclear. It would seem that it should either have been added to all paragraphs, or, more plausibly, to none, since the overarching phrase (“The NHS belongs to all of us...”) already introduces the idea that people should take some responsibility. Alternatively, perhaps the type of responsibility addressed here differs from the others, but if so, it is not clear from the wording alone in what sense, and what taking (some) responsibility means in the respective cases. It is also interesting that although organ donation is addressed, there is no reference to, for example, donating blood, tissue or bone marrow.

Responsibilities in the NHS Constitution – status of responsibilities

The Constitutional Advisory Forum to the Secretary of State for Health (CAF) published a report in December 2008 which summarised the findings of a comprehensive consultation exercise which was overseen by Strategic Health Authorities over the summer of that year. It also builds on reflections of CAF members who attended consultation discussion events and received formal representations from stakeholders. The CAF noted in its summary of the consultation exercise that the section on responsibilities was generally supported, but that there had been “anxieties about enforcement”. While some respondents took the view that “only those responsibilities with clear sanctions for individuals would have an impact” others worried that “excessive or inappropriate enforcement might deter people from the services they need” (CAF, 2008).

The overall status of the responsibilities is generally non-binding and merely aspirational. There is no mention of positive or negative conditionalities (financial or other incentives or disincentives, or other forms of rewards or penalties) with the exception of the third set of obligations, which implies that legal action based on general provisions of the law may be taken where other NHS users or health care staff are aggressed, harassed or harmed. It is noteworthy that the explanatory text of the consultation document stated unambiguously: “We have firmly ruled out linking access to NHS services to any sort of sanction for people not looking after their own health” (DH, 2008). Perhaps some of the anxieties which the CAF reported might have been avoided if this, or a similar phrase clarifying the primarily aspirational nature of the responsibilities, had been included in the opening paragraph of the actual text of the responsibility section, in the first or second principle of the Constitution as a whole, or, alternatively, in the documents Your Guide to the proposed NHS Constitution, (intended primarily for the public) or the Handbook to the draft NHS Constitution, rather than just in the explanatory notes. However, neither the draft version of the constitution nor its final version include an explicit acknowledgement that responsibility-related denial of treatment is not an option. The CAF's report concludes that

“the responsibilities in the Constitution as currently drafted do not need strengthening. The [DH] will, however, need to argue for an understanding of ‘responsibility’ that reaches beyond duties and sanctions to a concept linked to ‘mutuality’- as taking responsibility with consequences for all rather than sanctions for individuals [for] responsibility to the NHS is, at bottom, a responsibility to each other” (CAF, 2008).

Discussion: the case for a wider concept of responsibility

As the brief quotes from the CAF's report demonstrate, for many, the concept of responsibilities is intrinsically linked to being held responsible. Responsibilities without sanctions appear pointless, while putting sanctions in place may risk penalising people unduly. The CAF suggests that this situation can be resolved by emphasising the notion of mutuality. However, without further detail, it is not clear that this concept by itself offers a useful strategy. Among other things, mutuality has a strong notion of reciprocity, which may well be compatible with penalising people where they do not honour their obligations in the community, or where they take unreasonable risks that seem unjustifiable to others. By contrast, the concept of solidarity, understood as the notion of giving without expectation of return – and thus distinct from strict mutuality or reciprocity – may be a more promising starting point. I have attempted elsewhere to sketch a more comprehensive account of health responsibility (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2008) and will focus here on a basic conceptual analysis of the term responsibility as commonly used in order to prepare the ground for a plausible wider concept of health responsibility, and to make the argument that the responsibilities included in the NHS Constitution are, in principle, useful ones and suited to complement a SDH approach (see also Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2009).

When we say “person X is responsible for p”, we may mean a range of different things. Sometimes, distinct notions are made explicit, but other times, several meanings may be in use simultaneously, whether explicitly or implicitly. Much confusion arises from not distinguishing clearly between these different meanings, or from not being explicit about which sense is intended in endorsements or criticisms of particular responsibility-related policies. It is also important to distinguish whether we are using the phrase in a backward-looking sense (where, for example, we assess someone's past behaviour that is correlated to some health outcome) or in a forward looking one (where we may want to specify what people should do in the future).

In a backward-looking sense, the phrase “person X is responsible for p” may mean:

X has played a certain causal role in having brought about p.

X has played a certain causal role in having brought about p, and should recognise this.

X has played a certain causal role in having brought about p, should recognise this, and try to avoid doing so in the future.

X has played a certain causal role in having brought about p, should recognise this, try to avoid doing so in the future, and make good any costs (with or without being blamed) for reasons of distributive justice.

X has played a certain causal role in having brought about p, should recognise this, try to avoid doing so in the future, make good any costs, and, in cases where X requires treatment, may be given a lower priority than patients whose behaviour played none or a lesser role in contributing to their health care needs (typically with attribution of blame).

It is not uncommon for commentators to focus on the last type only, and/or jump straight from the first to the last type, assuming that having established some degree of causal or role responsibility, a person must also be held responsible (Daniels, Reference Daniels2007; Cappelen and Norheim, Reference Cappelen and Norheim2005; Heath, Reference Heath2008). But this is far from necessary. For example, the concept of solidarity as characterised above may mean that we are quite clear that a person's action played a causal role in producing a bad health outcome, but that this does not reduce the person's claims on the solidaristic community. Nonetheless we may find it useful to draw on some notions of responsibility. For example, in a given case where a person is responsible in one of the first three senses there may remain some degree of freedom for personal action and behaviour change even if environmental constraints have played a role, perhaps even a major one. Realising the scope for action in this area is important for avoiding fatalism and resignation, which may have a powerful grip on people struggling to maintain or improve their health. While it is difficult to disagree with the SDH approach's emphasis on the general need for improving environmental conditions, an exclusive or overly strong focus on the environment can overlook the degrees of freedom which people have, even in constrained conditions. For people to take action, then, it is necessary for them to realise the extent to which they contributed to, say, a bad health outcome, and, in this merely functional sense, to realise that they are, and can be, responsible.

In a forward-looking sense, “person X is responsible for p” may mean:

X should do p as no-one else can, in principle, (or will, practically) do p for X (eg: exercise more, eat less).

X should do p, as this will be good for the health of X.

X should do p, as this will be good for the health of others, or the operation of the health care system, even though X won't be penalised if p is not done.

X should do p, as this will be good for the health of others, or the operation of the health care system, and X knows that a penalty will be imposed if p is not done.

Again, it is far from necessary that the first or second type of responsibility, which may be called prudential responsibilities, automatically lead to the last type, which, together with the third, may be called responsibilities of justice.

Paragraphs one, two, four and seven of the responsibility section of the NHS Constitution helpfully emphasise the value of prudential responsibilities. Some health-related behaviours simply require that people individually do them, as no-one else will do them for them, and not even the most optimal environmental conditions will make them do them, in some sort of mechanistic way. It is in this somewhat banal, but nonetheless crucially important sense, that a range of health-related behaviours are personal responsibilities. Noting them and appealing to them in health promotion activities is relevant since it is up to us to decide on whether we wash our hands regularly, brush our teeth, exercise, see our GP when we are sick, are honest about our health-relevant information, take part in public health programmes, and so on. Advocating such responsibilities can result in clear personal benefits and is also likely to complement the SDH approach as it can help identify those social or other structural constraints that make it difficult for people to live healthily.

Furthermore, the Constitution's responsibilities one, four, six and seven clarify that achieving good health is necessarily a co-production process, requiring both individual and social action. The concept of co-production features prominently in other statues that fulfil a similar function as the NHS Constitution, such as the German Social Security Schedule (Sozialgesetzbuch V), which governs the provision of statutory health insurance. More recently, Forde and Raine (2008) have characterised co-production as the idea that: “responsibility for better health should be shared between society and the individual,...society's efforts for health improvement should be dovetailed with individuals’ and families’ efforts”. Central to their discussion is that polices are required that “support… people to engage with decisions about their own health”. This includes health-literacy campaigns and may also speak in favour of financial incentive or conditional cash transfer schemes, interventions whose potential is also noted in the CSDH's report. Again, drawing on individual responsibilities here complements the SDH approach, can help reduce fatalism and resignation, and can help make progress in developing and promoting peoples’ capabilities and agency.

Lastly, all of the Constitution's responsibilities also have a justice element, as they require consideration of the consequences which one's actions have for the health of others, or, in a more indirect way, for the efficiency with which the health care system can be operated. However, none of these obligations, except those falling under general legal provisions, are combined with legal or other penalties, and they concern entirely reasonable provisions. Complying with them, as far as can reasonably be expected of people in view of their respective circumstances, will again complement the SDH approach, as the most efficient health care system is the one that can make the biggest contribution towards the SDH approach's central goal of reducing avoidable health inequities, and improving the health of people individually and collectively as fairly, effectively and sustainably as possible.

Conclusion

One of the findings of the CSDH's report that received much coverage in the press around the time of the launch was the statistic that that a boy growing up in the deprived Glasgow suburb of Calton will live on average 28 years less than a boy born in nearby affluent Lenzie (54 vs 82 years). Equally, it remains the case that travelling eastbound on London's Jubilee Line from Westminster to Canning Town, life expectancy decreases with every tube stop by one year (77.7 vs 71.6 years, eight stops, London Health Observatory, 2005). Such figures illustrate in a very clear and powerful way the reality of the social determinants of health. The CSDH report presents a wealth of further evidence showing that we need to be concerned not only about the difference in quality of life and life expectancy between the best and the worst off, but also about the fact that there is a range of groups between these two extreme ends of the spectrum whose morbidity and mortality data demonstrate that there is a systematic and steady decline from the best to the worst off. Action on the social determinants of health is therefore urgently needed.

Appeals to individual responsibility generally do not sit easily with a social determinants perspective, for it is all too easy to “victim-blame” people in disadvantaged positions by holding them responsible for factors that are beyond their control. However, I tried to show here that it is not helpful to reduce the concept of personal responsibility to just one dimension. There are a variety of other, non-punitive senses which form part of a reasonable, fuller and more nuanced concept of personal responsibility for health, and these types of responsibility form an integral part of any health promotion activity. I also aimed to show that the responsibilities set out in the NHS Constitution should be seen as complementary to a SDH approach, as they can pinpoint those areas where social and structural determinants have especially strong effect; acknowledge the inevitable necessity of individual action that is required even when environments have been optimised to the maximum extent; underline the need for policies that build on promoting co-production of health; and help make the health care system, which plays an important part in the SDH approach (Marmot et al., Reference Marmot, Friel, Bell, Houweling and Taylor2008), as efficient as possible.

Clearly, whether or not these benefits will be secured depends on how the responsibilities will be implemented in further policy and practice (Klein, Reference Klein2008), and at this stage it is impossible to make any prognoses. Sceptics may reiterate that the final version of the constitution, just like its draft version, is nothing but “seven parts platitude, two parts mendacity, and one part hypocrisy” (Heath, Reference Heath2008), or they maybe concerned that what seems like a set of toothless motherhood and apple-pie responsibilities may just be the beginning of a slippery slope to binding and potentially penalising responsibilities as they have been implemented in other countries such as the US or Germany (for some detail see Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2007). However, I would suggest that the new NHS responsibilities have not only significance for health promotion campaigns that complement the SDH approach, but should also be welcomed on conceptual and strategic political grounds. For too long the responsibility debate has followed unhelpfully rigid left-right patterns, with people arguing in an all-or-nothing fashion for or against individual responsibility at the expense of social responsibility, or vice versa. The significance of the responsibilities set out in the NHS constitution, then, is that they demonstrate the limitations of these perspectives by shining the spotlight on the middle ground. Instead of tug-of-wars between the social versus individual responsibility camps we need genuine efforts to make the best of both approaches – and starting by introducing the idea of non-penalising personal responsibilities is an important step in the right direction.