Does UN peacekeeping promote democracy in conflict-affected countries? Among policy makers, especially in the EU and North America, democratizationFootnote 1 is widely viewed as indispensable for peace and security after civil war (European Union 2020; NATO Parliamentary Assembly 2019; Schmidt Reference Schmidt2019; UN General Assembly 2016). Few international organizations are as committed to democracy promotion as the UN: despite the UN’s increasing emphasis on stabilization and civilian protection, democracy promotion remains an “integral part” of the UN’s peacebuilding agenda (Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015, 513) and a “key goal” of UN missions (Fortna and Huang Reference Fortna and Huang2012, 804). This is true even in missions otherwise focused on stabilization, as in Mali, where holding elections was the UN Security Council’s “strongest political priority” (Day et al. Reference Day, Gorur, Holt and Hunt2020, 124). Democratization can shape the structure and legitimacy of states emerging from conflict, and can be crucial for validating peace agreements (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 196–8). As former UN Secretary-General Boutros-Boutros Ghali explains in his Agenda for Democratization, democracy “fosters the evolution of the social contract upon which lasting peace can be built” (Boutros-Ghali Reference Boutros-Ghali1996, 7). Not coincidentally, “Democracy and Governance” projects have received the second largest share of funding from the UN Peacebuilding Fund since its inception.Footnote 2

Yet although democracy promotion remains one of the UN’s most important policy goals, it continues to provoke theoretical debate and empirical controversy among scholars. Critics dismiss democracy promotion (and “liberal peacebuilding” more generally) as a neocolonial enterprise used by Western “empires in denial” (Chandler Reference Chandler2006) to maintain “essentially undemocratic societies” (Robinson 1996 in Paris Reference Paris2010, 344–5). Even skeptics who do not reject liberal peacebuilding altogether nonetheless express concern that democratization is “inherently conflict-exacerbating,” and that elections in particular create incentives for violence among losing candidates, leaving deeply fragmented societies less democratic and more vulnerable to conflict relapse (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 197–8). Others worry that UN missions may undermine democratization by providing material support to authoritarian governments (von Billerbeck and Tansey Reference von Billerbeck and Tansey2019) or by imposing the “benevolent autocracy” of international intervention on host states (Chesterman Reference Chesterman, Newman and Rich2004). Marten (Reference Marten2004, 155) goes so far as to dismiss the UN’s democracy promotion agenda as a “pipedream.”

Empirical evidence on the efficacy of UN democracy promotion remains limited and contradictory. Some studies suggest that the UN’s efforts to democratize conflict-affected countries only exacerbate the risk of renewed violence, perhaps because newly democratized institutions are too weak to effectively channel democratic contestation (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Paris Reference Paris2004). Others, however, suggest that delaying democratization endangers peace by allowing autocratic governments to maintain power (Carothers Reference Carothers2007; Mross Reference Mross2019). Some studies have found that UN interventions have a positive effect on the quality of democracy in countries recovering from civil war (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Heldt Reference Heldt, Fjelde and Höglund2011; Joshi Reference Joshi2013; Pickering and Peceny Reference Pickering and Peceny2006; Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015). But others have found the opposite—that UN missions have null or even negative effects on democracy (Bueno de Mesquita and Downs Reference Bueno de Mesquita and Downs2006; Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b; Fortna and Huang Reference Fortna and Huang2012; Höglund and Fjelde Reference Höglund and Fjelde2012).

These existing studies provide important insights into the relationship between peacekeeping, democracy, and civil war. But they are also limited in at least four important ways. First, their analyses typically end in the late 1990s or early 2000sFootnote 3 and thus omit some of the most ambitious multidimensional peacekeeping operations to date, including UNMIL in Liberia (2003–2018), ONUB in Burundi (2004–2006), UNOCI in Côte d’Ivoire (2004–2017), UNMIS in Sudan (2005–2011), MONUSCO in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (2010–present), UNMISS in South Sudan (2011–present), MINUSMA in Mali (2013–present), and MINUSCA in the Central African Republic (2014–present). Second, most previous studies operationalize UN intervention in rather coarse ways, distinguishing between “strong” and “weak” (Joshi Reference Joshi2013) or “hostile” and “supportive” peacekeeping operations (Pickering and Peceny Reference Pickering and Peceny2006) or between missions with observer, traditional, enforcement, or multidimensional mandates (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b). Although these distinctions are important, they capture only a fraction of the variation in the contents of UN mandates, the composition of the UN missions responsible for fulfilling those mandates, or the tactics that UN personnel adopt to execute mandated tasks in the field.Footnote 4

Third and related, although previous scholars have identified specific mechanisms linking peacekeeping to democratization (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b; Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015), most have been unable to test these mechanisms except in general ways, due in part to an absence of data on the nature and intensity of UN interventions. Finally, to the best of our knowledge, all prior studies estimate the effect of peacekeeping on democracy by comparing countries with UN missions to those without. Although peacekeepers tend to deploy to “hard” cases (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Gilligan and Stedman Reference Gilligan and Stedman2003; Fortna Reference Fortna2008a), thus potentially attenuating the relationship between peacekeeping and democracy cross-nationally (Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015), comparisons of such disparate settings require strong assumptions and create serious inferential challenges. Most studies also rely on selection on observables for causal inference and do not attempt to identify plausibly exogenous sources of variation in UN democracy promotion either within or across countries. As Walter, Howard, and Fortna (Reference Walter, Howard and Fortna2021, 1715) conclude in a recent review, the limitations and contradictions of existing research on peacekeeping and democratization “call out for additional work on this critical relationship.” We seek to answer this call by overcoming the limitations described above.

Our theoretical framework synthesizes insights from existing accounts of international intervention (Barnett and Finnemore Reference Barnett and Finnemore1999; Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Fortna Reference Fortna2008a; Howard Reference Howard2008; Walter Reference Walter1997) while introducing nuances that arise from the specific characteristics of UN missions on the ground. We begin by identifying three primary barriers to democratization in conflict and postconflict countries: a lack of (1) credible commitment to the democratic process, (2) security, and (3) capacity, broadly defined. We argue that UN missions can help overcome these barriers, but that their ability to do so varies as a function of their (1) mandates, (2) composition, and (3) tactics. Mandates that include democracy promotion can create a shared expectation that the international community will devote time and resources to democratization; this, in turn, can increase the credibility of armed actors’ commitment to the democratic process. Missions composed of large numbers of uniformed personnel can provide security for political parties, politicians, and voters, especially during periods of conflict (Fjelde and Smidt Reference Fjelde and Smidt2021); missions composed of large numbers of civilian personnel can build capacity by educating citizens, training political parties and elected officials, and restructuring electoral institutions, especially during periods of peace. Finally, missions that engage host governments in the process of reform can strengthen and legitimize the agencies and officials on whose initiative the success of democratization ultimately depends. Engagement is especially important during periods of peace, when host states are less preoccupied with counterinsurgency and more inclined to support the UN’s peacebuilding goals (Blair, Di Salvatore, and Smidt Reference Blair, Di Salvatore and Smidt2022).

To test our theory, we combine existing data on the number of uniformed personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa since the end of the Cold War with three original datasets capturing the contents of each mission’s mandate, the number of civilian personnel deployed to each mission, and the nature and intensity of each mission’s democracy promotion tactics in the field. We operationalize the quality of democracy using data from the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project; our results are substantively similar when we use Polity scores or Freedom House rankings instead. We estimate the relationship between peacekeeping and democracy within countries over time, using a variety of controls to mitigate time-varying confounders and country fixed effects to eliminate time-invariant confounders. We also use two different instrumental variables strategies to address the potential endogeneity of peacekeepers’ mandates and tactics to conditions on the ground. Although none of our identification strategies is flawless, together they help support a causal interpretation of our results.

Consistent with our expectations, we find that the quality of democracy improves when a new UN mission with a democracy promotion mandate is authorized or when the mandate of an existing mission is revised to include democracy promotion components. We also find that democracy improves as the number of personnel assigned to a UN mission increases but that the magnitude of the correlation is larger for civilian personnel than for uniformed personnel, especially during periods of peace. Also consistent with our expectations, we find that democracy improves when peacekeepers engage host governments in the process of reform, but only once a peace process has begun. While civil war is ongoing, the relationship between engagement and democracy reduces to a null. This is unsurprising, as host governments are unlikely to have the will or capacity to participate in democratic reforms while they are waging counterinsurgency. As a more exploratory exercise, we also test whether the relationship between peacekeeping and democracy varies with the specific activities peacekeepers pursue in the field—for example, training political parties, educating voters, or administering elections. We find that the relationship is driven by activities that target the electoral process specifically. We conclude by considering the implications of our results for the study and practice of peacekeeping in the future.

CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIZATION AFTER CIVIL WAR

Democratization is an arduous and uncertain process. We argue that promoting democracy in conflict-affected countries involves addressing three interrelated obstacles: a lack of (1) credible commitment to the democratic process, (2) security, and (3) capacity. First, as Rustow (Reference Rustow1970, 355) argues, democratization requires a commitment on the part of elites to “accept the existence of diversity in unity” and “institutionalize some crucial aspect of democratic procedure.” But in countries recovering from civil war, previously armed actors tend to be only weakly committed to democracy (Wantchekon Reference Wantchekon2004, 22) and may refuse to abide by the rules of the democratic process if doing so erodes their status. In the absence of some third party capable of enforcing the outcomes of elections, elites “lack a sense of credible commitment by their opponents” and thus fear fraud or refusal to accept legitimate results (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 200). In Angola in 1991, for example, leaders of the two competing factions were “not irrevocably committed to a democratic transition” at a time when “only a wholehearted commitment to democracy … might have made such sudden transition successful” (Ottaway Reference Ottaway and Kumar1998, 137).

The second obstacle is a lack of security. Violence tends to persist locally long after national peace agreements are signed, impeding democratization in myriad ways (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2012). Violence polarizes citizens, intimidates voters and candidates, and undermines the norms of peaceful participation that are essential to democracy (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Höglund Reference Höglund, Jarstad and Sisk2008). Previously armed groups may respond to violence by delaying or reversing their transition into political parties, thus emboldening spoilers to the peace. Government officials may also cite threats of violence as a pretext for canceling elections or postponing democratic reforms (Piccolino and Karlsrud Reference Piccolino and Karlsrud2011). Even if elections proceed, they are unlikely to produce “legitimate or widely accepted results” if they are conducted under conditions of “grave insecurity” (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 203).

The third obstacle is a lack of capacity, broadly defined. Some amount of state capacity is necessary for democracy to function (Linz and Stepan Reference Linz and Stepan1996). Between elections, government officials must be able to pass legislation, enact policies, and satisfy the needs of constituents. During elections, they must be able to train poll workers; establish polling sites; and print, transport, secure, and count ballots. Meeting these challenges requires funding and expertise, which tend to be scarce in countries suffering or emerging from civil war. A lack of capacity can afflict citizens and political parties as well. Citizens may lack the education and independent information necessary to understand their rights as voters, distinguish between rival candidates, or demand accountability from elected officials. Political parties may be poorly organized, may lack both financial and human resources (Höglund, Jarstad, and Kovacs Reference Höglund, Jarstad and Kovacs2009, 537), and may operate within party systems that are underdeveloped and untested (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 201). This is especially problematic when incumbents with a weak commitment to democracy are the only ones capable of mounting nationwide campaigns, as occurred, for example, in Cambodia in the 1990s (Brown Reference Brown and Kumar1998, 100).

HOW UN MISSIONS ADDRESS THE CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIZATION

Perhaps no other international organization is as committed to addressing these obstacles to democratization as the UN. But UN missions vary in their ability to promote democracy on the ground. We focus on three sources of variation in particular: mandates, composition (i.e., the number of uniformed and civilian personnel deployed to UN missions), and tactics (i.e., how UN missions pursue democratization in the field). Each source of variation corresponds to one of the obstacles described above. Together, they generate six empirical hypotheses for us to test.

ADDRESSING A LACK OF CREDIBLE COMMITMENT THROUGH UN DEMOCRACY PROMOTION MANDATES

Even the most ambitious peacekeeping operations vary in the contents of their mandates. Mandates are especially important for ensuring a credible commitment to democracy among the parties to the conflict and other stakeholders. Democracy promotion mandates signal the UN’s intention to devote sustained time and resources to democratization and the international community’s intention to support the UN’s efforts (Di Salvatore et al. Reference Di Salvatore, Lundgren, Oksamytna and Smidt2022). In this way, mandates create a shared expectation of an eventual democratic order in the host country (Metternich Reference Metternich2011, 910). This is especially important when setbacks in the democratization process arise (Rich Reference Rich, Newman and Rich2004, 83). For example, if peacekeepers cannot assist with elections because the government refuses to participate (as Laurent Gbagbo did from 2005 to 2009 in Côte d’Ivoire or as Joseph Kabila did in the Congo from 2016 to 2018), a democracy promotion mandate helps communicate that the mission will not simply abandon elections and that they will be held sometime in the future. Opposition parties, civil society groups, and other actors know this and can continue to plan for the eventual democratic transition.

Of course, mandates are not self-enforcing. But they are not cheap talk either. As Steinert and Grimm (Reference Steinert and Grimm2015, 519) note, “the mandate details what peacebuilders are supposed and allowed to do during a mission. It can therefore be assumed that democracy promotion is an integral part of peacebuilding activities in the field if specified accordingly in the respective mandate” (see also Heldt Reference Heldt, Fjelde and Höglund2011). Peacekeepers certainly do not comply with all mandate provisions all the time (Blair, Di Salvatore, and Smidt Reference Blair, Di Salvatore and Smidt2022). But compliance is still the norm, and the parties to the conflict can generally expect UN missions to abide by the provisions in their mandates. In our sample, for example, UN missions with democracy promotion mandates pursue democracy promotion tasks 85.5% of the time. The UN itself views mandates as a “statement of firm political resolve and a means of reminding the parties to a conflict and the wider UN membership of their obligation to give effect to Security Council decisions.”Footnote 5 Existing studies suggest that conflict parties understand this “reminder” and adjust their behavior accordingly. Metternich (Reference Metternich2011, 921), for example, shows that UN missions without a democratization mandate “cannot provide the necessary institutional framework that keep rebel leaders with large ethnic support from fighting.”Footnote 6

The proliferation of democracy promotion mandates across UN missions also reflects an “evolution of international norms” in favor of democratization (Di Salvatore et al. Reference Di Salvatore, Lundgren, Oksamytna and Smidt2022, 1). The UN often adopts democracy promotion provisions from previous mandates for newly authorized missions (Bellamy and Hunt Reference Bellamy and Hunt2019; Blair, Di Salvatore, and Smidt Reference Smidt2022, 9; Rich Reference Rich, Newman and Rich2004, 76)—a “cut-and-paste” approach that is central to our empirical strategy, as we discuss below. Repetition of this sort is also theoretically important, however, because it signals that democratic reform is central to the international community’s operational and normative priorities (for a similar argument on civilian protection, see Hultman Reference Hultman2013). Indeed, this is precisely why Security Council debates over democracy promotion provisions are often heated, and why foreign ministries involve themselves “as closely as possible” in drafting mandates’ language (Rich Reference Rich, Newman and Rich2004, 72–3). For example, the phrase “progress towards democratic governance” had to be removed from a draft resolution on UNITAMS in Darfur after Russia and China fiercely objected.Footnote 7 We would not expect to observe debates of this sort if democracy promotion mandates were mere cheap talk.

Nor are mandates merely artifacts of an existing commitment to democracy among the parties to the conflict. Even if the parties are reluctant to democratize, they typically cannot prevent the UN from issuing democracy promotion mandates altogether, as evidenced, for example, by Angola in the 1990s (Ottaway Reference Ottaway and Kumar1998, 137) and Côte d’Ivoire in the 2000s (Piccolino and Karlsrud Reference Piccolino and Karlsrud2011). There are exceptions, of course—Chad, for example, where the government’s intransigence forced a “race to the bottom” to remove components from MINURCAT’s mandate (Novosselof and Gowan Reference Novosselof and Gowan2012). But UN leadership has often proved adept at convincing host states to accept mandates they might otherwise find objectionable, for example by persuading them that progress on sensitive issues will attract foreign aid or generate public support for fledgling regimes (Sebastián and Gorur Reference Sebastián and Gorur2018). Indeed, the success of UN democracy promotion mandates often occurs in spite rather than because of an existing commitment to democratization. In Haiti, for example, a US-led multinational operation forcefully intervened in 1994 to restore democracy after a military coup. Despite the absence of any genuine democratic commitment among the parties, including the government, the subsequently deployed UN mission received a mandate to assist elections one year later. Although challenges remained, these elections appear to have contributed to the establishment of democracy in the country (Nelson Reference Nelson and Kumar1998, 80). Therefore we expect that

Hypothesis 1: The quality of democracy improves when a UN mission is mandated to pursue democracy promotion in the field.

Addressing a Lack of Security through UN Uniformed Personnel

Even peacekeeping operations with identical mandates may vary in their ability to execute mandated tasks. UN missions consist of a combination of uniformed and civilian personnel, both of which are critical for democracy promotion, but in different ways. Uniformed personnel are especially important for security. As the number of uniformed personnel deployed to a given UN mission increases, the mission should become better able to reduce violence, neutralize threats from armed actors, and create a stable and predictable environment for voters, candidates, and political parties (Di Salvatore and Ruggeri Reference Di Salvatore and Ruggeri2017; Fjelde and Smidt Reference Fjelde and Smidt2021). Uniformed personnel can also create space for civic engagement and have been associated with increased levels of peaceful protest in postconflict countries (Belgioioso, Di Salvatore, and Pinckney Reference Belgioioso, Di Salvatore and Pinckney2021). In principle, the host state could perform these functions on its own, but restructuring and retraining host state security forces is inevitably slow. Uniformed personnel can provide security while host state capacity is being built. We hypothesize that

Hypothesis 2: The quality of democracy improves as the number of uniformed personnel deployed to a UN mission increases.

Addressing a Lack of Capacity through UN Civilian Personnel and Democracy Promotion Activities

Equally if not more important are the civilian contingents that play an increasingly prominent role in peacekeeping operations (High-Level Independent Panel on United Nations Peace Operations 2015). Civilian personnel are especially important for capacity building, broadly defined (Blair Reference Blair2020; Reference Blair2021). Civilian contingents can educate citizens on electoral rules and procedures, encourage them to vote, and develop mechanisms for them to communicate their policy preferences to elected officials. Civilian personnel can also train political parties to recruit candidates and organize campaigns, provide technical assistance and professional development to improve host state efficiency and accountability, and observe elections to ensure they are conducted freely and fairly. Therefore we expect that

Hypothesis 3: The quality of democracy improves as the number of civilian personnel deployed to a UN mission increases.

Although both uniformed and civilian personnel can contribute to democratization, their relative importance is likely to vary with conditions on the ground. The UN is resource constrained, and there are limits to the number of personnel that can be deployed to any given UN mission in any given year. The UN must consider the marginal return on additional deployments given circumstances in the host country and must weigh the trade-offs of authorizing more of one category of personnel over another. Uniformed personnel are likely to be especially essential during periods of conflict, when threats to the safety of citizens, politicians, and government officials are imminent. Uniformed personnel can mitigate these threats in ways that civilian personnel cannot. In contrast, civilian personnel are likely to be especially vital during periods of peace, once the risk of violence has begun to subside and the need to educate voters, train political parties, strengthen host government institutions, and organize elections has become more urgent. Civilian personnel can perform these tasks in ways that uniformed personnel cannot. This is not to suggest that civilian personnel are entirely irrelevant during periods of violence or that uniformed personnel are entirely irrelevant during periods of peace. But we expect their relative importance to shift as conditions on the ground evolve:

Hypothesis 4: The magnitude of the relationship between UN personnel and the quality of democracy is (a) larger for uniformed personnel than for civilian personnel during periods of conflict and (b) larger for civilian personnel than for uniformed personnel during periods of peace.

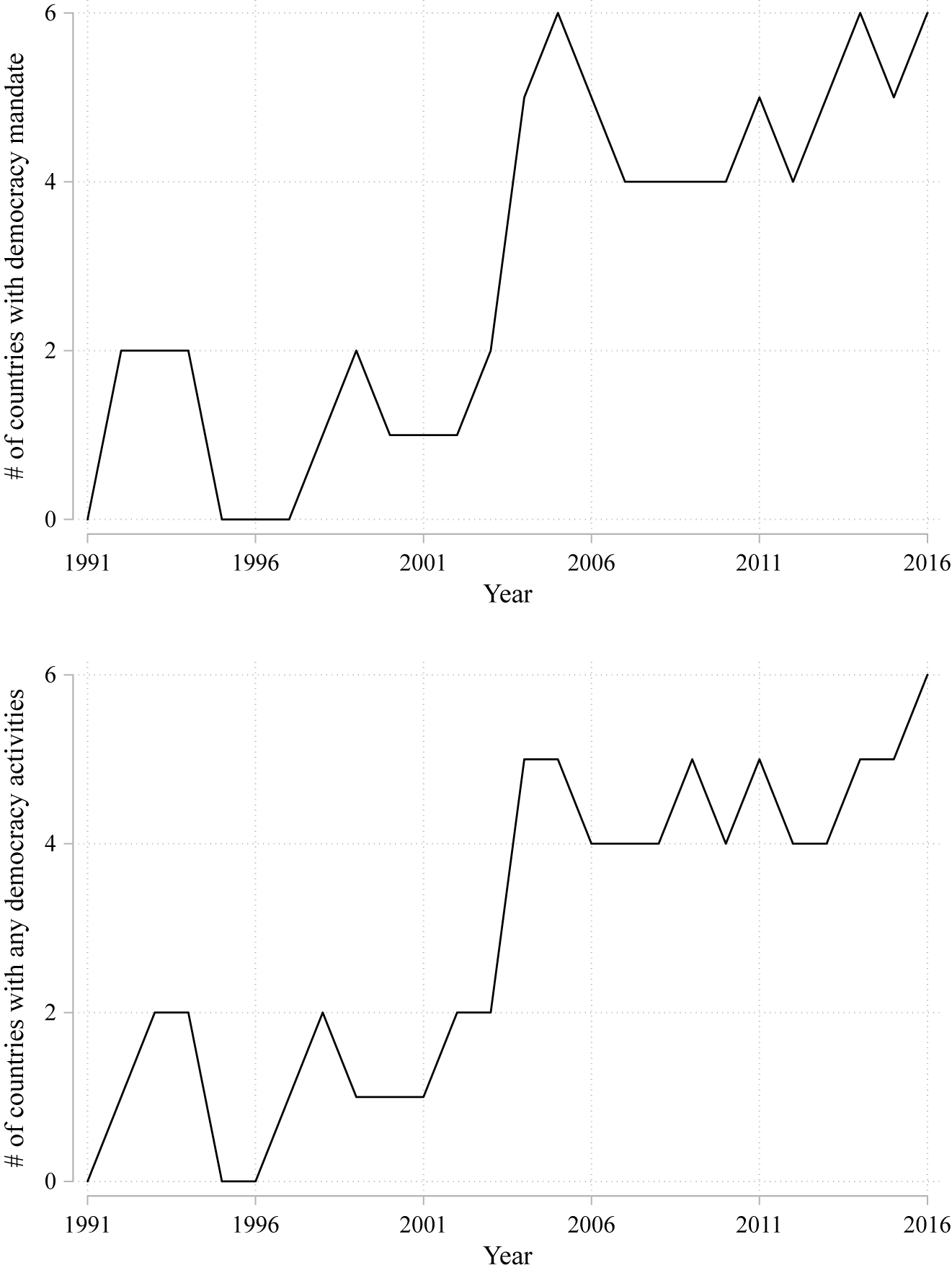

Even missions with similar mandates and similar numbers of uniformed and civilian personnel may vary in the tactics they use to promote democracy. As we show in Figure 1 below, although mandates and tactics are highly positively correlated, some UN missions pursue democracy promotion activities without being mandated to do so and vice versa. Missions with mandates to educate voters may decide to prioritize other goals; missions with mandates to train political parties may choose to redeploy resources and expertise to other purposes. These tactical decisions have important implications for democratization. Capacity building does not happen automatically or as a byproduct of other activities; it requires “targeted and planned substantive action by democracy promoters” (Steinert and Grimm Reference Steinert and Grimm2015, 519). Missions that neglect democracy promotion may delay or even reverse progress toward democratization. Therefore we hypothesize that

Hypothesis 5: The quality of democracy improves when a UN mission pursues democracy promotion in the field.

Figure 1. Democracy Promotion Mandates (Top) and Activities (Bottom)

Of course, UN missions vary not just in whether but also in how they implement mandated tasks. As Dorussen and Gizelis (Reference Dorussen and Gizelis2013, 696) note, the extent of peacekeepers’ involvement in host states “varies widely from technical assistance and monitoring to direct line authority or even direct implementation” (see also Caplan Reference Caplan2004). We seek to capture this variation by distinguishing between democracy promotion tactics that engage or bypass host governments. Engaging involves providing host governments with training, funding, and other forms of technical and material support as they pursue democratic reforms; bypassing involves registering voters, advising political parties and civil society organizations, or overseeing elections with no or minimal coordination with the host state.

As with composition, the efficacy of these different tactics is likely to vary with conditions on the ground. Engaging may be ineffective during periods of conflict (Narten Reference Narten, Paris and Sisk2009, 257), when host governments are unlikely to have the will or capacity to pursue democratization, and may impede democratic reforms (Sisk Reference Sisk, Paris and Sisk2009, 204). In Mali, for example, the exigencies of counterinsurgency against multiple armed groups made the government “reluctant” and “extremely slow” to execute its commitments under the 2013 Ouagadougou Preliminary Agreement and the 2015 Algiers Agreement, both of which included numerous provisions directed at strengthening Malian democracy (Day et al. Reference Day, Gorur, Holt and Hunt2020, 127-9).

Missions that engage host governments during ongoing civil war also risk being perceived as parties to the conflict, provoking local political opposition and potentially jeopardizing their relationship with important domestic stakeholders in the democratization process. Especially while conflict is ongoing, peacekeepers rely on the consent not just of the host state but also of the other belligerents; engaging during these periods can undermine the mission’s claim to impartiality and erode its legitimacy in the eyes of the other parties, weakening their commitment to reform (Rhoads Reference Rhoads2016; Sebastián and Gorur Reference Sebastián and Gorur2018). In South Sudan, for example, the eruption of violence in 2013 generated concern within the Security Council that “support to the government could be seen as politicizing the mission” (Day et al. Reference Day, Gorur, Holt and Hunt2020, 71–3), thus undermining other peacebuilding goals (including democracy promotion) in the long term. At worst, host states may capture whatever resources the UN provides during these periods and repurpose them for counterinsurgency.

Bypassing host governments during conflict may be the best (and sometimes only) way to improve the prospects for democratization once the violence subsides. But bypassing can also limit the effectiveness of democracy promotion activities during periods of peace. Activities that bypass host states in peacetime are unlikely to build (and may even weaken) their capacity to provide services to citizens—a perennial concern among scholars of foreign aid and other forms of third party public goods provision (Blair and Winters Reference Blair and Winters2020). Running this risk may be worthwhile to avoid politicizing the mission and inadvertently financing counterinsurgency during periods of conflict. During periods of peace, however, peacekeepers who bypass host states may have no or only weak effects on existing institutional arrangements; at worst, they may incapacitate and delegitimize precisely the same institutions whose capacity and legitimacy they are ostensibly mandated to promote (Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b), and may antagonize the same government officials whose cooperation is essential for the success of democratic reforms (Dorussen and Gizelis Reference Dorussen and Gizelis2013).

These dynamics are especially pronounced in transitional administrations. In Kosovo, for example, it took nearly 10 months after the end of the conflict for the UN Mission in Kosovo (UNMIK) to establish even the most rudimentary mechanisms of coadministration, and most of the mission’s activities involved “very limited consultation with local stakeholders” (Narten Reference Narten, Paris and Sisk2009, 264–5). UNMIK came to be viewed by many as an occupier, and the Kosovo Liberation Army began erecting “competing governmental structures” that later had to be dismantled (Beauvais Reference Beauvais2001, 1117). But even in UN missions that do not wield the same broad, intrusive authority as transitional administrations, bypassing host states can diminish the efficacy of democracy promotion activities. In Kosovo as elsewhere, the UN must balance competing priorities during the democratization process. It must build the capacity of host states but must do so without undermining its own legitimacy in the eyes of other stakeholders; it must retain the consent of host government officials but must do so without sacrificing the consent of citizens and the other parties to the conflict. During periods of civil war, we argue that the best way to balance these competing priorities is to bypass the host state; during periods of peace, the best way is to engage:

Hypothesis 6: The magnitude of the relationship between democracy promotion tactics and the quality of democracy is (a) larger when a UN mission engages rather than bypasses the host government during periods of peace and (b) larger when a UN mission bypasses rather than engages the host government during periods of conflict.

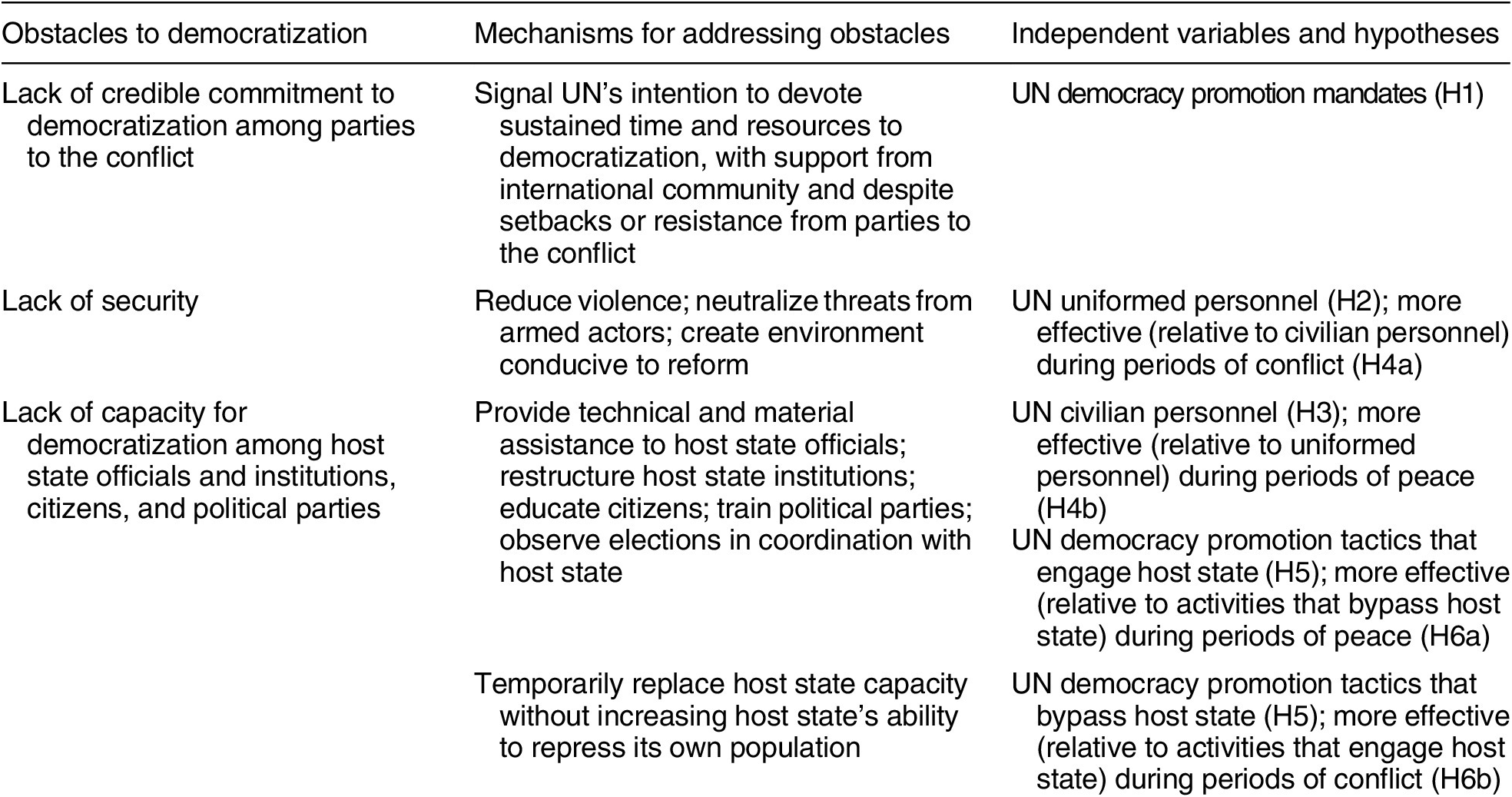

Table 1 summarizes our theory and hypotheses. Each source of variation in UN intervention corresponds to one of the three obstacles to democratization described above. But the correspondence is not perfect and the categories are not mutually exclusive. For example, large and increasing deployments of uniformed personnel may improve security but may also signal the UN’s intention to provide the resources necessary for democratization, thus increasing the credibility of domestic stakeholders’ commitment to the process (Ruggeri, Gizelis, and Dorussen Reference Ruggeri, Gizelis and Dorussen2013). Similarly, the tactics that UN missions use to promote democracy may build the capacity of host states but may also mitigate violence (Smidt Reference Smidt2021). Although we match specific sources of variation in UN intervention to specific obstacles to democratization, we acknowledge that some amount of overlap is inevitable in practice.

Table 1. Summary of Theory

We expect each of these factors—mandates, composition, and tactics—to improve the prospects for democratization independently of one another. But conditional and interaction effects are also possible. For example, although we expect UN missions with new democracy promotion mandates to improve the quality of democracy even if their civilian contingents remain unchanged, new mandates may be more effective if they are accompanied by new deployments of civilian personnel. Similarly, although we expect UN missions with growing uniformed contingents to improve democracy even if they only provide security, new deployments of uniformed personnel may be more effective if the missions to which they are deployed also promote democracy in other ways (e.g., by educating voters). We discuss these possibilities in further detail below.

RESEARCH DESIGN

We test our theory using four sources of data covering all conflict and postconflict sub-Saharan African countries between 1991 and 2016. We focus on Africa because it remains the locus of UN peacekeeping worldwide. Among the ongoing UN missions authorized after 1991 (hence excluding, e.g., missions in the Middle East authorized during the Cold War), six out of seven are in Africa. UN missions in Africa currently host more than 84% of all UN personnel deployed to peacekeeping operations around the world. UN missions in Africa also tend to have especially extensive mandates, in which democracy promotion is a core component. The prospects for (and obstacles to) democratization in Africa have been the subject of persistent scholarly and policy concern since at least the end of the colonial era. Africa is thus an important regional test case for understanding the relationship between peacekeeping and democracy in conflict-affected countries. We focus on the years since the end of the Cold War because the UN’s attempts to promote democracy have become especially active and ambitious during this period.

Measuring Variation in UN Peacekeeping

To test hypothesis 1, we code an indicator for UN missions with democracy promotion mandates using our original Peacekeeping Mandates (PEMA) dataset (Di Salvatore et al. Reference Di Salvatore, Lundgren, Oksamytna and Smidt2022). PEMA draws on resolutions establishing, extending, modifying, or overhauling the mandates of all UN missions in Africa from 1991 to 2016 and includes information on 41 tasks that these missions have been mandated to perform. We focus on four tasks in particular: voter education, assistance to political parties, assistance to democratic institutions (e.g., legislatures), and assistance with the planning and execution of elections, including provision of security at polling places. In Appendix D.1, we test a broader operationalization that includes assistance to media and civil society organizations as well; our results are substantively similar regardless.

Once the UN Security Council includes a given democracy promotion task in a mandate, we assume it continues to mandate that task unless and until it issues a new or revised mandate from which the task is omitted. If the new or revised mandate merely extends the previous one or makes only minor modifications, we assume the task is still included. Because UN mandates sometimes span multiple years, we lag our indicator by two periods to avoid reverse causality. As we show in Appendix D.12, our results are substantively similar using longer (or shorter) lags. We describe our coding rules in further detail in Appendix A. The top panel of Figure 1 plots the number of UN missions in Africa with a democracy promotion mandate over time.

To test hypothesis 2, we code the number of uniformed personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa using existing data from the International Peace Institute’s Providing for Peacekeeping (P4P) project.Footnote 8 Although P4P distinguishes between UN troops, police officers, and military observers, our theory does not generate distinct expectations for different categories of uniformed personnel and the pairwise correlations between categories tend to be high, creating problems of multicollinearity.Footnote 9 Therefore, we combine them into a single count. Because the UN records personnel numbers by fiscal rather than calendar year, we again lag our count of uniformed personnel by two periods in order to avoid reverse causality. Again, our results are substantively similar using longer or shorter lags. Figure A.1 in the Appendix plots the distribution of uniformed personnel across African countries over time.

To test hypotheses 3 and 4, we combine existing P4P data with another original dataset capturing the number of civilian personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa (Blair Reference Blair2020; Reference Blair2021). This dataset draws on annual budget performance reports from the UN’s Advisory Committee on Administrative and Budgetary Questions (ACABQ). Budget performance reports are available beginning in 1993 and distinguish between four categories of civilian personnel: international staff, national staff, government-provided personnel (GPPs), and UN Volunteers (UNVs). We collapse these categories into a single count and then lag the count by two periods to avoid reverse causality. Our results are again substantively similar using longer or shorter lags. Figure A.2 in the Appendix plots the distribution of civilian personnel across the nine African countries for which budget performance reports are available.Footnote 10

To test hypothesis 5, we code an indicator for UN missions that engage in democracy promotion activities on the ground using our original Peacekeeping Activities (PACT) dataset. The PACT dataset draws on UN Secretary-General progress reports, which are typically published four to seven times per year for each mission. PACT sythesizes information from 465 progress reports covering 24 missions in 14 countries. To maximize data quality, over one-third of all progress reports (selected at random) were double- or triple-coded; the rate of intercoder agreement is generally very high.Footnote 11 Although PACT records 37 different activities, we again focus on four: voter education; assistance to political parties; assistance to democratic institutions; and assistance with elections. In Appendix D.2 we again test a broader operationalization that includes assistance to media and civil society; our results are substantively similar regardless.

Because UN Secretary-General progress reports sometimes span two years, we again lag our indicator by two periods; our results are substantively similar using longer or shorter lags. We describe our coding rules in further detail in Appendix B. In Appendix D.4, we also test a continuous measure designed to capture the intensity with which each UN mission executes democracy promotion activities in the field; again, our results are substantively similar regardless. The bottom panel in Figure 1 plots the number of UN missions in Africa that pursue any democracy promotion activities over time.

Finally, to test hypothesis 6, we use PACT to distinguish activities that engage the host government from those that bypass it. Activities that engage the host government include monitoring, advocacy, and provision of technical assistance (e.g., training) or material support (e.g., funding) for democratization. Activities that bypass the host government involve what Dorussen and Gizelis (Reference Dorussen and Gizelis2013, 696) call “direct implementation”—that is, attempts to enact democratic reforms without host government involvement. We describe our approach to distinguishing engagement from bypassing and provide empirical examples in Appendix B. The top panel of Figure A.3 in the Appendix illustrates the variation in engagement and bypassing over time; the bottom panel illustrates the variation in the four democracy promotion activities captured in PACT.

Our theory suggests that each of our independent variables should be positively correlated with the quality of democracy in host countries. It also suggests that the quality of democracy should improve when one of our independent variables changes, even if the others do not. In other words, we do not expect the effect of any one variable to be conditional on the others. For example, we expect new democracy promotion mandates to improve the quality of democracy in host countries by signaling the UN’s commitment to the democratization process, even if UN missions do not immediately begin implementing democracy promotion activities on the ground. For these reasons, and because the correlations between our independent variables tend to be high,Footnote 12 we generally test our hypotheses independently of one another. This implies, for example, that we do not control for the number of civilian personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa when testing the relationship between democracy and UN democracy promotion mandates. We explore the possibility of conditional and interaction effects in Appendices D.10 and D.11, respectively. For reasons mentioned above, we interpret these conditional and interactive results somewhat cautiously.

Timing

Our dataset on civilian personnel covers fewer years (1993 to 2016) and countries (nine) than the other three datasets. To maximize statistical power and generalizability, we do not restrict our sample to the countries or years for which all four datasets are available. This is potentially problematic when testing hypothesis 4, which requires comparing uniformed and civilian personnel. In Appendix D.5 we show that our results are substantively similar when we restrict our sample of uniformed personnel to the country-years for which data on civilian personnel are also available.

Ideally we could test the relationship between peacekeeping and democratization both while UN missions are on the ground and after they withdraw. Unfortunately, the long lifespan of most contemporary peacekeeping operations makes this all but impossible. Instead, we run our analyses in five different ways: in the full sample of country-years, in a subsample of country-years in which civil war is ongoing, and in subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years, according to the UCDP armed conflict dataset. In some cases (e.g., Angola, Burundi, Mozambique, and Sierra Leone) these specifications encompass the full trajectory from deployment to withdrawal. But even in the other cases, understanding the effects of long, complex peacekeeping operations while they are still on the ground is important in and of itself (Blair Reference Blair2020; Reference Blair2021). As Howard (Reference Howard2019, 23) rightly notes, “researchers, peacekeepers, and the victims of civil war do not have the luxury to wait.” For an approach similar to ours, see Fortna (Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b).

Operationalizing Democracy

We operationalize democracy using the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) “electoral democracy” index, which consists of five components intended to capture Dahl’s conceptualization of polyarchy: an elected executive, free and fair elections, universal suffrage, freedom of association, and freedom of expression alongside alternative sources of information (Dahl Reference Dahl1971; Teorell et al. Reference Teorell, Coppedge, Lindberg and Skaaning2019). This index is advantageous because it corresponds to widely adopted definitions of democracy in political science, and to the UN’s own definition as well.Footnote 13 V-Dem has also been found to outperform the most common alternatives (Polity and Freedom House) in the coherence of its definitions, measurement strategies, and aggregation procedures (Boese Reference Boese2019). As robustness checks, in Appendix D.6 we replicate our analyses using Polity scores (Marshall and Gurr Reference Marshall and Gurr2020) and Freedom House “political rights” rankings.Footnote 14 Our results are substantively similar regardless.

ESTIMATION AND IDENTIFICATION

Like all studies of peacekeeping, ours is susceptible to selection bias. It is not clear whether selection should bias our estimates toward or away from the null. Peacekeeping operations tend to deploy to the “hardest” cases for peace (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Fortna Reference Fortna2008a; Gilligan and Stedman Reference Gilligan and Stedman2003); if the UN Security Council similarly authorizes more ambitious democracy promotion mandates or larger personnel deployments in the “hardest” cases for democratization, then we should expect the correlation between peacekeeping and democracy to be biased toward the null. Our data lend some credence to this expectation. Intuitively, and following our theoretical framework, we should expect democratization to be most difficult during periods of conflict, when threats to security are especially severe. If peacekeeping operations were systematically selecting into “easy” cases, we would expect them to contract during wartime and expand during peacetime. But this is not the case. If anything, our data suggest that peacekeeping operations tend to be statistically significantly larger during periods of conflict.

Importantly, this pattern holds for both uniformed and civilian personnel, even though the latter are not well equipped to neutralize violence during civil war.Footnote 15 Although UN mandates are slightly more likely to include democracy promotion components during periods of peace, the difference is small and not statistically significant.Footnote 16 Missions are also more likely to pursue democracy promotion activities during peacetime, but again, the difference is not statistically significant.Footnote 17 We interpret our analyses that disaggregate UN activities by type (e.g., voter education vs. support to political parties) or by degree of engagement with the host state as somewhat more suggestive, as we do not have an identification strategy to isolate the causal effects of distinct types of activities or different degrees of engagement. Taken together, however, the patterns in our data suggest that UN missions generally do not select into easy cases for democratization.

We further minimize bias by using country fixed effects to eliminate some of the most important time-invariant confounders identified in previous studies of peacekeeping and democratization such as civil war cleavages (e.g., ethnic vs. political), incompatibilities (e.g., government vs. territory), and modes of termination (e.g., one-sided victory vs. negotiated settlement), as well as the location, topography, and colonial histories of host countries (Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b). We also control for six potentially problematic time-varying confounders: population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) living in the host country.Footnote 18 Because we lag our independent variables by two periods to avoid reverse causality, we lag our controls by three periods to avoid posttreatment bias. We report results from random effects and lagged dependent variable models in Appendices D.7 and D.8, respectively; the latter allow us to mitigate potential confounding due to the quality of democracy in the past. Our results are substantively similar regardless.

We complement our fixed effects estimators with two instrumental variables strategies designed to address the potential endogeneity of UN mandates and activities to conditions in the field. Both strategies exploit well documented patterns of mimicry and path dependence within the UN system. The UN Security Council has long adopted a “copy-and-paste,” “off-the-shelf” approach to drafting mandates (Bellamy and Hunt Reference Bellamy and Hunt2019). This approach is apparent in the language of mandates themselves, many of which prescribe virtually identical tasks for wildly disparate settings (Howard Reference Howard2019, 9). Empirically, once the Security Council decides to include democracy promotion in the mandate of one mission, it becomes more likely to include democracy promotion in the mandates of other missions as well, regardless of conditions on the ground—indeed, even when those conditions militate against success (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2009, 252). In a similar way, once one UN mission decides to undertake democracy promotion activities in the field, other missions become more likely to do so as well.

Our two instrumental variables strategies exploit these dynamics. Mimicry and path dependence ensure that the probability that any given UN mission is mandated to pursue democracy promotion in a given year depends in part on the number of other missions that are mandated to do the same. For a given mission i in year t, we can therefore use the proportion of missions other than i with democracy promotion mandates as an instrument for mission i’s democracy promotion mandate in that same year. Likewise, we can use the proportion of missions other than i that pursue democracy promotion activities in the field as an instrument for mission i’s pursuit of democracy promotion activities. As we demonstrate below, these two instruments are strong first-stage predictors of their respective endogenous regressors.

Both of these instrumental variables strategies hinge on two assumptions. First, we assume that the proportion of UN missions other than i that have democracy promotion mandates or pursue democracy promotion activities is independent of other determinants of democracy in mission i’s host country, including any preexisting commitment to democratize. This independence assumption seems likely to hold in our case. UN mandates are the result of negotiations within the Security Council and may be driven as much by external factors (such as the economic and geopolitical interests of the P5) as by conditions internal to the host country (Higate and Henry Reference Higate and Henry2009). Moreover, as discussed above, the Security Council often drafts mandates that reflect broad trends in the UN’s priorities—for example, the relatively recent emphasis on corrections and justice sector reform as essential to peacebuilding (Blair Reference Blair2020; Reference Blair2021)—rather than specific considerations in the field. If mission i’s mandate and activities are only loosely tied to conditions on the ground in its own host country, then the mandates and activities of all other missions are unlikely to be tied to conditions in mission i’s host country any more closely.

Second, we assume that the only mechanism through which the proportion of UN missions other than i with democracy promotion mandates or activities can affect democracy in mission i’s host country is through mission i’s own democracy promotion mandate or activities. This excludability assumption seems likely to hold as well. Although there are several potential exclusion restriction violations, none seems especially plausible or problematic. One possible violation might arise as a result of personnel transfers across UN missions. For example, if personnel in missions other than i develop the knowledge and experience necessary to implement democracy promotion activities effectively and if they are then transferred to mission i, then mission i’s capacity to promote democracy may improve. But this is only relevant if mission i pursues democracy promotion on the ground; in other words, this alternative mechanism is still channeled through the mechanism we propose. Moreover, “second-level organizational learning” should help ensure that democracy promotion expertise is at least partly institutionalized within the UN system (Howard Reference Howard2008) such that it does not depend on the configuration of personnel across UN missions at any given time.

Another possible violation might arise as a result of changes in peacebuilding priorities across the international community. For example, if foreign donors and international NGOs interpret the growing proportion of UN missions with democracy promotion mandates as a signal that they too should prioritize democratization, then the quality of democracy in mission i’s host country may improve as a result of their efforts, which may be undertaken independently of the UN. But this assumes a level of coordination between the UN’s objectives and those of other actors that seems unlikely to materialize in practice, especially within a single year, and especially given the array of domestic and international factors that have been shown to influence agenda setting within the Security Council (Binder and Golub Reference Binder and Golub2020). The UN’s democracy promotion efforts are also far more prominent and ambitious than those of any other bilateral or multilateral actor, especially in the African countries in our sample. Of course, the exclusion restriction is an untestable assumption, and we cannot eliminate all potential violations. Nonetheless, the assumption seems plausible in our case.

RESULTS

Table 2 reports the correlation between V-Dem’s electoral democracy index and a dummy indicating whether each UN mission in Africa has a democracy promotion mandate in a given year. We report results for the full sample of conflict and postconflict African countries between 1991 and 2016 (column 1); a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2); and subsamples of countries that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years, as defined by UCDP (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). All specifications include country fixed effects and controls for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. (Tables with coefficients on these control variables are available in Blair, Di Salvatore, and Smidt Reference Blair, Di Salvatore and Smidt2023.)

Table 2. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Mandates

Note: Coefficients from ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Consistent with hypothesis 1, we find that democracy improves when a UN mandate is issued or revised to include democracy promotion. The relationship is positive and statistically significant across specifications, though, perhaps unsurprisingly, it is smallest during periods of conflict, when the challenges to democratization are especially acute. To put these correlations in perspective, the predicted score on the V-Dem index among African countries without a UN democracy promotion mandate is roughly 0.338. In countries with a democracy promotion mandate, the predicted score is roughly 0.459—an improvement of approximately 36%. This is slightly larger than the improvement we would expect to observe in an African country that transitions from civil war to at least one year of peace (0.105 points on the V-Dem index) and is between 13 and 15 times larger than the improvement we would expect to observe from each additional year of peace thereafter (between 0.008 and 0.009 points on the V-Dem index).

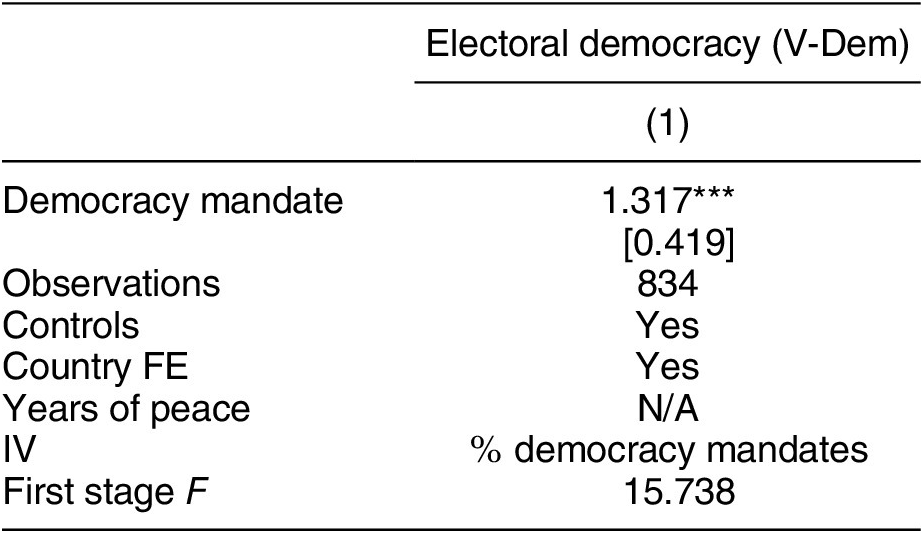

Table 3 replicates our analysis in Table 2 using instrumental variables. For a given mission i in year t, we use the proportion of missions other than i with democracy promotion mandates as an instrument for a dummy indicating whether mission i has a democracy promotion mandate in year t as well. Table 3 reports results for the full sample only: as we show in Appendix D.9, our instrument is strong in the full sample—with a first-stage F statistic of more than 15, well above the “rule of thumb” threshold of 10 (Sovey and Green Reference Sovey and Green2011)—but it becomes weaker when we split the data into smaller subsamples. With this caveat, our results in Table 3 are again consistent with hypothesis 1. Moreover, as we show in Appendix D.9, our second-stage coefficients remain large and positive but are imprecisely estimated in all subsamples of countries that have been at peace for at least one year.

Table 3. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Mandates Using Instrumental Variables

Note: Coefficients from two-stage least squares regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample only. Instrument is the proportion of other UN missions with democracy mandates. We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 4 reports the correlation between V-Dem’s electoral democracy index and the number of uniformed personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa. Uniformed personnel are coded in units of 1,000; all specifications include the same controls and country fixed effects as in Table 2. Consistent with hypothesis 2, we find that the quality of democracy improves as the number of uniformed personnel increases. This relationship is again positive and statistically significant across specifications, but is smallest during periods of ongoing conflict. For every additional 1,000 uniformed personnel, our model predicts an improvement of roughly 0.008 points on the V-Dem index. Although this is less than one-tenth of the magnitude of the improvement we would expect to observe in a country that transitions from civil war to at least one year of peace, it is roughly equivalent to the improvement we would expect to observe from each additional year of peace thereafter.

Table 4. Electoral Democracy and UN Uniformed Personnel

Note: Coefficients from OLS regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 5 reports the correlation between electoral democracy and the number of civilian personnel deployed to each UN mission in Africa. Consistent with hypothesis 3, we find that the quality of democracy improves as the number of civilian personnel increases. The relationship is again smallest during periods of ongoing civil war. For every additional 1,000 civilian personnel, our model predicts an improvement of 0.035 points on the V-Dem index. This is roughly one-third of the improvement we would expect to observe in a country that transitions from civil war to peace and is roughly four times larger than the improvement we would expect to observe from each additional year of peace thereafter. Also consistent with hypothesis 4, the correlation with civilian personnel is between six and 10 times larger than the correlation with uniformed personnel during periods of peace, and the gap between the two correlations is smallest during periods of conflict. As we show in Appendix D.10, this result holds when we include uniformed and civilian personnel in the same regression. Contrary to hypothesis 4, however, the correlation with civilian personnel remains five times larger than the correlation with uniformed personnel even while civil war is ongoing. We return to this result in the conclusion.

Table 5. Electoral Democracy and UN Civilian Personnel

Note: Coefficients from OLS regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

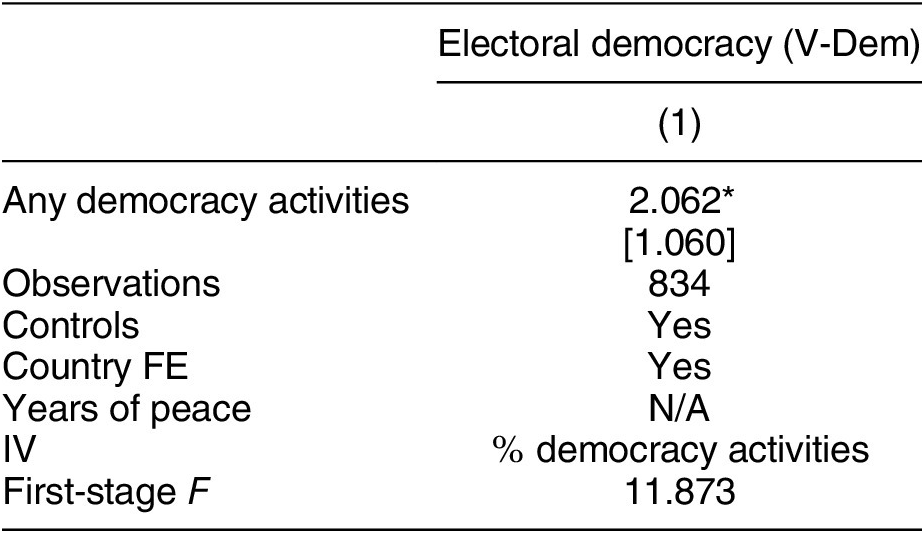

Table 6 reports the correlation between the V-Dem index and a dummy indicating whether each UN mission in Africa pursues democracy promotion activities in the field. Consistent with hypothesis 5, we find that democracy improves when UN missions actually pursue democracy promotion. When UN missions do not pursue democracy promotion, the predicted score on the V-Dem index among all African countries in our sample is roughly 0.339; when they do, the predicted score is 0.446—an improvement of roughly 31%. Table 7 replicates the analysis in Table 6 using instrumental variables, focusing on the full sample. Our results are again consistent with hypothesis 5, though they fall just short of statistical significance at the 95% level (p = 0.052). As we show in Appendix D.10, although our first stage is weak when we subset to countries that have been at peace for one or more years, the second-stage point estimates remain large and positive (though not statistically significant).

Table 6. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Activities

Note: Coefficients from OLS regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 7. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Activities Using Instrumental Variables

Note: Coefficients from two-stage least squares regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample only. Instrument is the proportion of other UN missions with democracy activities. We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Table 8 reports the correlation between electoral democracy and UN democracy promotion activities, distinguishing between activities that engage the host state (row 1) and those that bypass it (row 2). Consistent with hypothesis 6, we find that the correlation is between four and 11 times larger when UN missions engage rather than bypass host states during periods of peace. Conversely, during periods of conflict, the correlation is more than twice as large when UN missions bypass rather than engage host states, though neither correlation is statistically significant at conventional levels. This too is consistent with hypothesis 6. As noted above, we interpret these results somewhat cautiously, as the decision to bypass or engage may be endogenous to the host state’s existing commitment to democratization and we do not have valid instruments for engagement or bypassing specifically. Missions are more likely to bypass host states during periods of conflict and more likely to engage during periods of peace, suggesting that engagement is indeed more common when the host state’s commitment to democratization is likely to be relatively high—though, importantly, these differences are not statistically significant at conventional levels.Footnote 19 Though only suggestive, our results are nonetheless consistent with our hypothesis that peacekeepers are more effective at promoting democracy when they engage host states during periods of peace and when they bypass during periods of civil war.

Table 8. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Activities Disaggregated by Degree of Engagement with Host State

Note: Coefficients from OLS regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

EXTENSIONS AND ROBUSTNESS CHECKS

Further Disaggregating Democracy Promotion Activities

Democracy promotion can take multiple forms and target multiple actors and institutions—not just host states but also voters, political parties, civil society organizations, and the electoral process itself. We do not have strong theoretical priors about which of these strategies is most effective or an identification strategy to isolate the causal effects of different forms of democracy promotion. As an exploratory exercise, in Table 9 we distinguish between the four categories of democracy promotion in PACT: voter education, training of political parties, support for democratic institutions, and assistance with the conduct of elections. Of these four categories, we find that assistance with elections is the most consistently positively correlated with the quality of democracy in the host country. Support for democratic institutions is positively correlated with democracy as well, but only weakly so and only in countries that have experienced at least three years of peace. We return to this result in the conclusion.

Table 9. Electoral Democracy and UN Democracy Activities Disaggregated by Type of Activity

Note: Coefficients from OLS regressions with country fixed effects. We report results for the full sample (column 1), a subsample of countries with ongoing civil wars (column 2), and subsamples that have been at peace for at least one, two, or three years (columns 3, 4, and 5, respectively). We control for population, GDP per capita, foreign aid, literacy, fuel exports, and the number of refugees and IDPs living in the host country. Standard errors are in brackets; *p < 0.10, **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01.

Testing for Conditional and Interaction Effects

As mentioned above, although we expect mandates, composition, and tactics to improve the prospects for democratization independently of one another, conditional and interaction effects are also possible. We explore these possibilities in Appendices D.10 and D.11, respectively. As we show in Appendix D.10, our results remain substantively similar when we test for conditional effects (e.g., by including civilian personnel and democracy promotion activities in the same regression simultaneously). Our results in Appendix D.11 are more mixed. In general, we do not find evidence of interaction effects: in most specifications, the coefficients on the interaction terms are small and not statistically significant. The only important exception involves civilian personnel: when we interact civilian personnel with any of our other three proxies for UN presence (uniformed personnel, democracy promotion mandates, or democracy promotion activities), the interaction terms are negative and statistically significant.

This is surprising. Importantly, however, these negative interaction effects appear to be driven primarily by periods of conflict. Moreover, as the marginal effects plots in Appendix D.11 illustrate, the deployment of additional civilian personnel during periods of conflict makes the relationship between the quality of democracy and our three other proxies for UN presence less positive but generally does not make the relationship negative (at least not statistically significantly so).Footnote 20 In this sense, although the negative interaction terms are surprising, they are not entirely inconsistent with our theory. As discussed above, there are limits to what civilian personnel can accomplish while civil war is ongoing. It is possible that expanding civilian contingents during periods of conflict diminishes the effectiveness of other UN democracy promotion mechanisms, for example if civilian personnel require protection from their uniformed counterparts or if they prioritize long-term goals (like reforming electoral institutions) over potentially more urgent short-term priorities (such as protecting civilians), thereby stretching the mission’s human and financial resources too thin.

Again, we interpret these results somewhat cautiously, and there may be more complex interaction effects that we are unable to examine here (for example, a quadruple interaction between democracy promotion mandates, uniformed personnel, civilian personnel, and democracy promotion activities). With that caveat, the interaction effects in Appendix D.11 suggest that expanding both the uniformed and civilian components of peacekeeping operations simultaneously may not be an efficient use of resources, especially during periods of conflict. It may be preferable to wait to expand the civilian components until after a peace process has begun.

CONCLUSION

Taken together, our results suggest that UN intervention helps overcome challenges to democratization in conflict-affected countries. Consistent with our theory, we find that the quality of democracy improves when a UN mandate is authorized or revised to include democracy promotion; when the number of uniformed or (especially) civilian personnel deployed to a UN mission increases; and when the mission actually attempts to educate voters, train political parties, support democratic institutions, or assist with elections. Although these are correlations rather than relationships of cause and effect, we use multiple identification strategies to mitigate bias and support a causal interpretation of our results. In more suggestive exercises, we find that the magnitude of the improvement is larger when UN missions engage rather than bypass host governments, especially during periods of peace, and larger for election assistance than for other forms of UN democracy promotion.

Our analyses do, however, leave several questions unanswered. How long does it take for democracy to improve after a UN mission receives a democracy promotion mandate or after it begins implementing democracy promotion activities on the ground? What happens when a democracy promotion mandate is withdrawn or when a mission stops executing democracy promotion tasks? Are there outliers—cases in which the quality of democracy stagnates or decays despite the UN’s efforts? We explore these questions in the Appendix. In Figures A.4 and A.5, we show that democracy generally begins to improve shortly after a democracy promotion mandate is issued and democracy promotion activities commence—sometimes in the first year, sometimes one or two years later. In Tables A.54 through A.61 we also show that our results are robust to longer lags of our independent variables, suggesting that the improvement tends to persist while the UN is on the ground.

As we show in Figures A.4 and A.5, some countries’ V-Dem scores erode after a democracy promotion mandate is withdrawn or democracy promotion activities cease (Sierra Leone, for example), but in most cases they do not revert to baseline levels. There are, however, exceptions. In Burundi, the quality of democracy rose dramatically beginning in 2004 as violence abated and ONUB deployed to oversee elections stipulated in the 2000 Arusha Agreement. But conflict between the government and the last remaining rebel group (Palipehutu-FNL) continued, the government of newly elected President Pierre Nkurunziza asked ONUB to draw down, and the quality of democracy soon began to decay. In 2010, Nkurunziza was reelected in a landslide after a campaign of intimidation and repression forced all other candidates to withdraw. Burundi’s scores on the V-Dem index continued to fall thereafter.

In other cases—most notably the DRC—the quality of democracy begins to decay while the UN is still on the ground, even after years of democracy promotion. Indeed, the DRC’s V-Dem scores are consistently lower than predicted by our models. This is perhaps unsurprising, as the Congo has long been recognized as one of the most challenging environments for international intervention, with a protracted and immensely complex civil war; an enormous land mass; and a long history of government corruption, negligence, and abuse. It has confounded the UN for decades (Autesserre Reference Autesserre2009). These outliers notwithstanding, the correlations we observe between peacekeeping and the quality of democracy are generally positive and robust to different specifications.

Our findings have at least four important implications for the theory and practice of peacebuilding. First, previous accounts have emphasized the role that third parties can play in neutralizing spoilers (Walter Reference Walter1997), mitigating violence (Di Salvatore and Ruggeri Reference Di Salvatore and Ruggeri2017; Fortna Reference Fortna2008a; Hultman, Kathman, and Shannon Reference Hultman, Kathman and Shannon2016), and building the capacity of host states (Doyle and Sambanis Reference Doyle and Sambanis2006; Howard Reference Howard2008). Our results reinforce the importance of these efforts not just for peace but for democracy as well. Second, commentators both within and outside the UN system have argued that the Security Council should invest more resources in the civilian components of peacekeeping operations (Blair Reference Blair2020; Reference Blair2021; UN Security Council 2000). Our results lend credence to these arguments, at least during periods of peace. Although uniformed personnel can help provide security, our results imply that, for most missions, the marginal return on additional civilian personnel likely exceeds the marginal return on additional uniformed personnel, at least for purposes of promoting democracy and at least once a peace process has begun.

Third, critics often warn that international democracy promotion risks undermining domestic institutions and weakening the incentives of local reformers, thus diminishing the prospects for democracy in the long term (Fortna Reference Fortna, Jarstad and Sisk2008b; Pouligny Reference Pouligny2000). Although our results generally do not validate these concerns, they do support the idea that there are trade-offs involved in, for example, expanding civilian contingents while conflict is ongoing and large deployments of uniformed personnel are already in the field, or in bypassing host states once a peace process has begun. That said, the consistently positive correlation between UN engagement and democratization also contradicts the more sweeping claims of skeptics who believe third-party democracy promotion does more harm than good (Marten Reference Marten2004).

Finally, some observers argue that the international community is too quick to impose elections on weak and war-torn states, where institutions are fragile and the risk of violence is high (Brancati and Snyder Reference Brancati and Snyder2013; Flores and Nooruddin Reference Flores and Nooruddin2012). Although not conclusive, our results suggest that the positive association between peacekeeping and democratization may in fact be driven first and foremost by the UN’s support for electoral organization and security, even relatively early in the peace process. This finding complements several recent studies (Fjelde and Smidt Reference Fjelde and Smidt2021; Smidt Reference Smidt2020; Reference Smidt2021), and suggests that UN missions can help enable free, fair, and peaceful elections, even in some of the world’s weakest and most war-torn states, with potentially important implications for the quality of democracy in these settings.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422001319.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/UOYDHN.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ursula Daxecker and other participants in the Folke Bernadotte Academy workshop on “The Pursuit of Peaceful Polling” (December 2020) for their generous comments. We are grateful to the Folke Bernadotte Academy for their financial support and to Omar Afzaal, Samuel Berube, Victor Brechenmacher, Erin Brennan-Burke, Alexa Clark, Rachel Danner, Mara Dolan, Dylan Elliott-Hart, Karla Ganley, Ugochi Ihenatu, Julia Kirschenbaum, Ian Lefond, Divya Mehta, Ruth Miller, Remington Pontes, Lucy Walke, and Yijie Zhu for their excellent research assistance.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The authors affirm this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.