Globally, disasters caused by natural or man-made hazards have become more frequent and severe in recent decades. 1 According to the Nepal disaster risk portal, earthquakes, landslides, floods, glacial lake outburst floods, fires, droughts, and avalanches are common natural hazards in Nepal. 2 Nepal is situated in a seismically active zone and ranks 11th for earthquake risk in the Global Report on Disaster Risk. 3 Earthquakes can have direct health impacts, including deaths and injuries, and indirect impacts, such as population displacements and economic hardships. Evidence suggests that the human cost of earthquakes is greater in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) due to risk factors such as high vulnerability, weak health systems, and limited resources for preparedness. 4

Nepal was hit by a 7.8 magnitude (Richter scale) earthquake on April 25, 2015, which was followed by a Richter scale 6.8 magnitude earthquake on May 1. 5 These 2 large-scale quakes affected 31 of 77 districts in Nepal and caused nearly 9000 deaths and over 22,000 injuries. 5 Over 600,000 houses were destroyed, leaving 650,000 families displaced. 5 Despite the anticipated high disaster risk in Nepal, there has been a lack of long-term and sustainable efforts to address disaster risk management (DRM) for earthquakes. 5 The Nepalese Government attempted to respond to the immediate needs of affected communities but was unable to fulfil the demand quickly enough. The government immediately appealed for international assistance; however, due to geographical and infrastructural challenges, it took longer than expected for assistance to reach the affected areas. Reference Basu, Ghosh and Jana6

Community health workers (CHWs) are indigenous community members who work as frontline health-care professionals in underserved areas for underprivileged people. Reference Love, Gardner and Legion7 The World Health Organization (WHO) in 1989 defined the roles of CHWs as “members of the communities where they work, should be selected by the communities, should be answerable to the communities for their activities, should be supported by the health system but not necessarily a part of its organization, and have shorter training than professional workers”. Reference Lehmann and Sanders8

In Nepal, the role of CHWs is fulfilled through the cadre of 52,000 female community health volunteers (FCHVs) known as “Mahila Swasthya Swoyem sewika” under the Ministry of Health and Population. 9 This FCHV program started in 1980 primarily to support family planning by distributing contraceptive supplies in their communities. Reference Kandel and Lamichhane10 Currently, FCHVs in Nepal have become an important group in national health programs, primary health care, and the national health system. They help to reduce health inequities at the grassroots, promoting health for all, particularly people in local and remote communities. Reference Khatri, Mishra and Khanal11,Reference Schwarz, Sharma and Bashyal12

During response and recovery following the 2015 earthquakes, remote villages had difficulties accessing relief aid and assistance due to geographical inaccessibility. Reference Fredricks, Dinh and Kusi13 For countries with limited resources and population living in difficult areas, CHWs may be the only option available to assist people at the time of crisis following a disaster. CHWs reside in the communities they serve, placing them in the position to aid the households under their care at the time of emergencies. Studies conducted in the aftermath of the earthquakes in Nepal found that disaster-related trainings to FCHVs can be beneficial, and the study also discovered that disaster-related training could support FCHVs to build confidence and provide guidance for their work. Furthermore, the mental health and support services provided by the FCHVs after the earthquakes were found to be vital for communities. Reference Kc, Gan and Dwirahmadi14 These included survival skills of remaining calm and to search for safe spaces, conducting group support meeting for mothers once a month to discuss and resolve community issues and conflicts etc.

Despite the implementation of the Nepalese national disaster policy in 2009 and the recognition of FCHVs’ involvement during the 2015 earthquakes, the roles of FCHVs have not been well incorporated in national DRM. 5 Therefore, to strengthen their capacities during emergencies, it is important to identify their roles and what needs improving. In a scoping review by Miller et al., it was empathized that the “bottlenecks” to CHWs service delivery needed to be addressed to achieve impact, as well as addressing additional challenges faced in humanitarian settings. The key challenges identified from this review included the competencies of the CHWs and their supervisors, but also the transition between development and humanitarian programing. Reference Miller, Ardestani and Dini15 This study aimed to explore the meaning and significance of FCHVs’ experience during the 2015 disaster to identify facilitators and barriers for their work. Through highlighting these, this study also aimed to identify capacity development contributing factors to improve FCHVs’ performance in DRM, including the availability of training and supervision, and access to medical supplies. Due to the importance of the supervisors and the system of CHWs identified in the previous review, Reference Miller, Ardestani and Dini15 health managers who supervised the FCHVs in the same health facilities during and after the earthquakes were recruited for key informant interviews in February 2021. This report constitutes 1 of the case studies in a World Health Organization (WHO) -funded research project “Health workforce development strategy in Health EDRM: evidence from literature review, case studies and expert consultations”. Reference Hung, Mashino and Chan16

Methods

Study Design

This qualitative study used semi-structured in-depth interviews with 24 FCHVs and 4 health managers to explore their experiences during the 2015 earthquakes through open-ended questions. The participants were selected from 2 districts in Nepal, namely Gorkha and Sindhupalchock. FCHVs were selected purposively: (1) FCHVs who worked during and after the 2015 earthquake in these districts: and (2) FCHVs who continued to work at the time of the study.

Study Setting

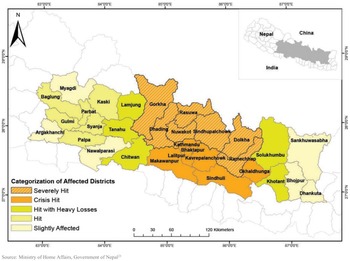

The WHO situation report identified 14 districts as severely affected by the earthquakes. 17 Two districts, Gorkha and Sindhupalchock, were selected as Gorkha was the epicenter of the earthquakes and Sindhupalchock had the highest death rate. Reference Chaulagain, Gautam, Rodrigues, Gautam and Rodrigues18,Reference Sharma, Kc and Subedi19 Both districts had the highest economic disaster effects per person (average values > NPR [Nepalese Rupee] 130,000 per person ≈ USD 1115) (Figure 1). 20 A brief profile of the districts is included in the supplementary file.

Figure 1. Map of the affected districts in the 2015 Nepal earthquakes. 21

Design of the Interview Guide

The interview guide was designed to explore FCHVs’ level of knowledge on earthquakes and their experience in the 2015 earthquakes (Supplementary File 1). It included (1) personal particulars, (2) knowledge on earthquakes, (3) FCHVs’ experience during the early response, (4) FCHVs’ roles in response, (5) quality and acceptance of their work, (6) training needs in disaster response, (7) supervision and leadership, and (8) motivation and difficulties in responding to earthquake situations. Pilot testing was conducted to assess the feasibility and applicability of the guide, and modifications were made before finalizing it.

Study Procedure and Data Analysis

The audio-recorded interviews were conducted in Nepalese and were documented by a note-taker. The content of the field notes was transcribed immediately after the interviews to maintain transparency. The interviews were later translated into English.

The sample size was determined by the point of reaching data saturation. Data saturation is reached when “there is enough information to replicate the study when the ability to obtain new information has been attained, and when further coding is no longer feasible.” Reference Fusch and Ness22 Peer debriefing was conducted by sharing data with several colleagues who hold no personal interest in this project. A thematic analysis method was used for data analysis. Then, data familiarization and coding were conducted to derive patterns and themes. Last, clustering and comparison were performed to draw conclusions.

Ethical Consideration

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethical Review Board, Nepal Health Research Council. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Confidentiality was maintained by keeping personal information anonymous.

Results

The participants were aged between 34 and 60 y. Less than half of the FCHVs had worked for over 20 y, and the majority served over 100 households. All the FCHVs were married. Table 1 summarizes the participant characteristics.

Table 1. Characteristics of the selected FCHVs

The data analysis identified 5 themes: (1) early response of FCHVs during the earthquakes, (2) FCHVs’ access to medical supplies, (3) training-related factors for FCHVs on earthquake response, (4) leadership and supervision for FCHVs during the earthquake, and (5) motivation factors for responding to health emergencies.

-

1. Early Response of FCHVs During the Earthquakes

All FCHVs said that they had provided services before any assistance arrived. One FCHV said: “We provided treatment as we couldn’t just watch when people were suffering from injuries.” Another FCHV said: “I started providing basic health services after the earthquakes. When national/international assistance arrived, they acknowledged FCHVs’ work which determined how important our roles were.” When all the FCHVs were asked if it was their responsibility to respond in health emergencies, most of them agreed: “We must do what we can because we know how to respond. If someone is cut and bleeding, we have the skills and supplies to deal with it.” However, 1 FCHV did not think it was their role, but she did it for self-satisfaction.

All the FCHVs stated that they aided local people to the best of their abilities. Most FCHVs provided first aid and water, sanitation, and hygiene-related services, for example, treating minor cuts and bruises, distributing soap, and conducting health awareness programs on proper handwashing techniques. One FCHVs elaborated on first aid services, “People with minor injuries were treated with betadine, whereas people with headache and other common health issues were managed by establishing a makeshift health clinic in the community by FCHVs.” Another FCHV stated: “Water was heavily polluted due to the earthquake, so we advised the community people to drink boiled or filtered water. Moreover, as many toilets were destroyed, we advised people to build temporary toilets.” Other services during this phase included emergency transport management and health information provisions, such as healthy diets for children, pregnant women, and lactating mothers. One FCHV said “We did not have stretchers, so I made a stretcher using a bed sheet and bamboo and transported an injured person to local hospital.” Further to providing general health information, over half of the FCHVs claimed that they provided information to reduce further health risks from disasters such as staying in safe areas and avoiding at-risk areas.

According to several FCHVs, they also provided mental health and psychological support during the disaster response: “We suggested to be calm and organising group meetings for mothers to share problems in the communities.” One FCHV mentioned: “We advised people not to worry/panic/fear but to carry on with their everyday activities while staying safe.” Another FCHV stated: “We created some space for recreation to prevent people from falling mentally ill. We were also assigned to collect data on people with mental illness during the post-disaster phase.”

Most of the FCHVs experienced the added workload from 5-6 d in a month to 10-15 d during the emergencies, sometimes during the night. They felt overburdened by the work during the earthquake response and struggled to balance their family responsibilities and the disaster response activities in communities. One FCHV stated: “We had problems in our own home, but we had to rush out when someone got sick or needed some help.”

-

2. FCHVs’ Access to Medical Supplies

All FCHVs said that access to regular supplies of common medicines and first aid equipment, such as paracetamol, povidone-iodine, oral rehydration salt (ORS), scissors, cotton, bandages, and thermometers was crucial during the emergencies. Over half of the FCHVs stated that they had enough access to medical supplies during the disaster. One FCHV indicated: “all the first aid medical supplies I had remained safe because my house was made of concrete. So, I was able to provide healthcare services during the emergencies.” However, all of the participants often experienced the shortages of supplies. A few FCHV participants said: “There were regular shortages of medical supplies in nearby health post, so we didn’t have continuous supplies in the emergencies. We didn’t have necessary supplies to treat children with diarrheal diseases, so we only gave suggestions and referred them to health institutions.”

-

3. Training-Related Factors Affecting Earthquake Response

Most of the participants said that they had received disaster response training and thought that all FCHVs should receive disaster response training. One FCHV explained that receiving disaster training would help people to make decisions during emergencies: “People are uncertain about many things during disaster situations, for example, things like where to go and what to do. If I can spread information and increase awareness in my community, people could decide and act more quickly. Hence such training is very necessary.” Another FCHV stated that the training improved her confidence level: “I had no training before the earthquakes, but a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) provided training on earthquake response. We felt empowered and gained confidence in our practice.”

A few FCHV participants did not receive any training and felt: “I worked in an office in the disaster response team but I was not provided with any disaster-related training after the earthquake. If we had such training beforehand, we could have saved many more lives.” The managers believed that some FCHVs were not fully competent in disaster response activities. However, all 4 managers believed that FCHVs could be important for future disasters with appropriate training. One of the managers described FCHVs’ contribution in the disaster: “We have been able to provide good services in the health sector only because of FCHVs’ hard work. During the 2015 disaster, mass awareness programs in communities became successful only because of their help and support. Hence, we did not have to suffer from any secondary disasters, such as post-earthquake epidemics or gender-based violence.”

All participants also emphasized the importance of reinforcing regular refresher training. One FCHV said: “We have not received training for a while since the last one. This resulted in the deterioration of service quality.” Another participant mentioned: “We need regular follow-up training to improve and maintain our skills and knowledge.” In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a few FCHVs thought that regular training on handling the epidemics would be beneficial, saying that: “In the time of corona, we couldn’t do much because we do not have any training on how to handle the pandemic.” Some managers also said: “There is inadequate refresher training for FCHVs. The government should provide regular and up-to-date training to FCHVs on how to manage all health emergencies.”

Despite the increased workload during the 2015 disaster response phase, most participants recalled that they had continuously provided good quality services. One FCHV said: “I believe that FCHVs received recognition for the good service after the quakes.” Another FCHV said, “I was awarded by the local government for my contribution during the earthquake response.” When the FCHVs were asked if their work quality would be hampered with additional roles, responsibilities, and training in disaster response, most of them believed that it would not be affected. Some described the relationship between their aspiration to be an FCHV and the work quality: “We have worked in communities for so long, I am sure that our quality stays the same.” “I became an FCHV to serve communities, which brings me happiness. So, work quality would not change.”

One FCHV pointed out a lack of quality assessment mechanisms for their work performance: “We report and submit our service data to the health post staff who compile and send it to the higher authority but there are no official mechanisms to evaluate the quality of our work.” All the health managers interviewed were also confident that FCHVs’ work quality would not decrease with additional duties. However, another manager pointed out, “it needs to be well-planned to ensure that FCHVs will not be overwhelmed with extra responsibilities in disaster response. If managed properly, they could be a prominent resource for disaster relief services and information to local communities.”

A manager pointed out that “It could be more effective to provide training to increase their knowledge and skills according to their capabilities and competencies.” Two health managers thought that FCHVs competencies would not improve unless the recruitment process is more systematized: “There were no clear entry guidelines or criteria in FCHVs’ recruitment process in the past and many were selected based on general literacy. Nowadays, most of FCHVs are required to have completed school education on a secondary level.” “It is important that all FCHVs have a zeal for providing services and assisting communities. However, it is also important that they can uptake and understand the content of disaster training.”

-

4. Leadership and Supervision for FCHV During the Earthquakes

The participants had different experiences on leadership and supervision during the earthquake response. The majority were supervised by their health managers. The managers organized monthly meetings with FCHVs to guide them on their responsibilities. All 4 health managers stated that they supervised FCHVs’ work: “During the emergencies, we directed FCHVs by guiding them on which areas to visit. FCHVs visited their allocated areas to collect information, such as the number of injured people and missing people, the situation of new mothers and people with disabilities. We also monitored and evaluated their work.”

Some of the FCHVs also worked with external organizations. One FCHV described the supervision mechanism within the organizations, “Officials from the Oxfam and health post gave us training and visited us in our community to see whether we worked or not.” Another FCHV said: “We were mainly instructed by health posts but we also worked with other organisations like Tulsi Mehar and United Nations Development Programme during the disaster.” A few FCHVs mentioned that they were not supervised by anyone but they did their jobs: “We provided services based on our observation because we weren’t given any instructions after the earthquake.”

-

5. Motivation Factors for Responding to Health Emergencies

When the FCHVs were asked what motivated them to respond in the emergency, many of them answered that it was not because of financial allowances and social recognition in communities but an act of volunteerism and their responsibilities. An FCHV expressed, “My first FCHV allowance was one hundred Nepalese Rupees which is not enough to motivate me. What motivated me the most was the feeling of helping someone and most importantly it is the fact that I am serving for my community, we agreed to work as a volunteer and the recognition from the government and society motivates us to work rather than the nominal allowances.”

Some health managers indicated that during the emergencies, some FCHVs received allowances from external organizations for disaster response activities while no additional allowances were provided by the government. A few managers mentioned that fair incentives should be provided to FCHVs for their work. As 1 manager explained “We need a mechanism or system not only to gain social recognition, but also to support their livelihood, FCHVs have to leave their household and agricultural works to work for us. If we could provide them some incentives, they would do happily, and their family also would support them.”

Discussion

This study investigated the roles and experience of FCHVs in the 2015 Nepal earthquake disaster. Our findings indicated that the FCHVs immediately responded to the disaster before any national or international response arrived by applying their skills and knowledge to provide multiple community health services, such as first aid, safe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programs, and mental health care. These findings were consistent with previous studies conducted in Nepal Reference Fredricks, Dinh and Kusi13,Reference Kc, Gan and Dwirahmadi14 and a scoping review study on CHWs in humanitarian settings. Reference Miller, Ardestani and Dini15

In 2011, the Global Health Workforce Alliance, United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), WHO, and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) published a joint statement on the role of CHWs during health emergencies. 9 It stated that CHWs should be an integral component of the health workforce to achieve public health goals because they can improve access to health care in local communities and play key roles in program sustainability, especially in LMIC settings. FCHVs in Nepal have great potential to provide life-saving support during health emergencies as they have good knowledge and understanding of local health risks, needs, and vulnerabilities. Hence, it is important for FCHVs to be recognized as a crucial health workforce group and to be integrated with national health systems to provide community-based primary health-care services during health emergencies.

This study also identified facilitating factors and barriers that influenced the roles and capacities of FCHVs to undertake effective disaster response activities during the 2015 disasters. First, our findings suggest that receiving disaster-related training appeared to have improved FCHVs’ performance and confidence level in dealing with emergency situations and that there is a lack of regular disaster preparedness and response training for FCHVs in Nepal. A systematic review on the roles of CHWs in LMICs reported that relevant training before emergencies can improve the quality of disaster response and is associated with longer service delivery times. Reference Kok, Dieleman and Taegtmeyer23 Several studies conducted after the Nepal earthquakes also reported that disaster-related training for FCHVs would be beneficial to provide guidance and to build FCHVs’ confidence. Reference Fredricks, Dinh and Kusi13,Reference Kc, Gan and Dwirahmadi14,Reference Horton, Silwal and Simkhada24 This is not limited to resource-constrained settings.

CHWs can play a pivotal role throughout the disaster management cycle in developed countries. Reference Nicholls, Picou and McCord25 Well-trained CHWs are key to timely responses, which can reduce further adverse health impacts in communities. Reference Nicholls, Picou and Curtis26 An effective way to protect public health is to train and educate local health workers to enable them to identify hazards and health risks specific to communities, to lower their vulnerability and strengthen emergency response. Reference Hung and Otsu27 Experience from Sichuan earthquake in China found that chronic disease management was a gap in the post disaster response, Reference Hung, Lam and Chan28 and community health emergency and disaster risk management (Health EDRM) initiative should address a comprehensive range of health education topics to meet the future needs. Reference Hung, MacDermot and Chan29 Furthermore, previous review of the global experience of CHWs highlighted the wide discrepancies in the level of education, duration of CHW training, and the level of supervision during practice. Formalized training instituted in Nepal FCHVs will be important evidence for the most appropriate level of training for CHWs in other countries to develop a competent health workforce for Health EDRM. Reference Bhutta, Lassi and Pariyo30

Second, this study found that the FCHVs did not have efficient coordination, leadership, and supervision, suggesting a need for better mechanisms and structures in the Nepalese health system for managing and evaluating CHWs’ practice during emergencies. Others have found that a lack of sufficient supervision and instructions for FCHVs during the 2015 Nepal earthquakes contributed to the inefficient disaster response. Reference Horton, Silwal and Simkhada24 Insufficient supervision can be a major challenge to program implementation and sustainability. 31

A review on CHWs’ roles in LMICs showed that availability of supportive supervision, communication, and coordination with other health-care professionals is associated with higher service performance. Reference Hill, Dumbaugh and Benton32 Supportive supervision is defined as “a process of guiding, monitoring, and coaching workers to promote compliance with standards of practice and assure the delivery of quality care service.” Reference Crigler, Gergen, Perry, Perry and Crigler33 This important component for strengthening CHWs’ capacity requires a well-established systematic structure, advanced planning, and integration of CHWs’ roles in public health/primary health-care systems. Alternative approaches, such as group supervision, peer supervision, and community supervision, can be useful and may be more cost and time efficient in local settings. Reference Crigler, Gergen, Perry, Perry and Crigler33 Furthermore, supervision can be more effective when it is context-specific and community focused and targets quality assurance, problem-solving, and skills development. Reference Crigler, Gergen, Perry, Perry and Crigler33,Reference Roberton, Applegate and Lefevre34 Pre-establishing clear reporting lines should also improve coordination and supervision mechanisms, resulting in improved disaster response activities. 9

Third, the FCHVs often experienced shortages of key medical commodities as reported elsewhere in Nepal. Reference Baral, Uprety and Regmi35 The national FCHV survey also identified the availability of key commodities is crucial. Reference Bhattarai, Khanal and Khanal36 Reduced access to medical equipment during emergencies could prevent a timely response. To increase access to medical equipment in future emergencies, it is important to integrate their roles and functions into the national health systems and to recognize CHWs as a key Health EDRM workforce groups. Reference Hung, Mashino and Chan16,Reference Hung and Otsu27 This may provide them with more consistent access to public sector commodity supply chains. Reference Baral, Uprety and Regmi35

Last, concerning FCHVs’ motivating factors for their willingness to work during disaster response, the major factor was an act of volunteerism whilst nominal allowances for increased workload had little impact. A similar national-level study reported that FCHVs were often overburdened by their work and were dissatisfied with government allowances in general. 37 Therefore, it is important to consider an appropriate level of allowance for additional responsibilities and to secure timely payment to increase and maintain their willingness to work during emergencies.

Health EDRM emphasizes a “people- and community-centered approach” as community members are often first responders to health emergencies, and community-based actions are essential during health emergencies. 38 This case study identified that CHWs were a vital Health EDRM workforce group in communities and provided critical health care services during emergencies. To maximize existing health systems, services, and health workforce in all phases of disasters (prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery), the roles of CHWs need to be recognized, established, and scaled up by training and equipping them for action and by supporting them as valued members of the health system. Integrating CHWs into the health system and maximizing their potential contribution in the context of primary health care will also help move closer toward achieving universal health coverage goals. Reference Evans, Hsu and Boerma39 This will require strong commitments from governments and supporting partners to promote CHWs by strengthening existing health systems, providing resources and planning employment, supervision, support, and career development.

Limitations

First, the decision of data saturation was according to the authors’ judgement where no new information for further coding was possible. However, this may be considered subjective, and more objective methods like the one proposed by Guest et al. may be more preferable. Reference Guest, Namey and Chen40 Second, the response from the participants might be subject to recall bias, given the length of time since the earthquakes. Last, the participants were selected from the 2 most severely affected districts in the earthquakes. The implication of study findings may be unique to these areas and may not be generalizable in other poor resource settings.

Conclusions

Community health workers, like FCHVs in Nepal, play an essential role not only in establishing universal health coverage during their routine contributions to their communities, but also in accomplishing community health emergency and disaster risk management. Strong leadership from the public sector and sustained investments will be essential for the development of a prepared and effective community health workforce to prepare for and mitigate the effect of future disasters and emergencies. This study also confirmed that there is a strong need to provide further research evidence to support their practice and to improve the potential capacity of CHWs during health emergencies in Nepal.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2022.47

Availability of Data and Materials

Data may be available from the corresponding author on a specific request.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants for taking the time to participate in the study.

Authors’ Contributions

H.K. and K.H. contributed to the conception of the study. H.K. designed the study, contributes to the coordination of the study and the acquisition of the study data. H.K. analyzed the data, K.H. and C.G. interpreted data for the work. H.K. drafted the manuscript, all authors critically revised the manuscript and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This research is the result of a study conducted in the framework of the International PhD in Global Health, Humanitarian Aid and Disaster Medicine jointly organized by the Università del Piemonte Orientale (UPO) and the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). This research was supported by the World Health Organization Centre for Health Development (WHO Kobe Centre – WKC: K19008).

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Ethical approval obtained from Nepal Health Research Council (ref no. 1925, Jan 2021).