The provision of specialist mental health services for people early in the course of their psychotic disorder is a matter of considerable debate worldwide (Reference McGorry, Edwards and MihalopoulosMcGorry et al, 1996; Reference Pelosi and BirchwoodPelosi & Birchwood, 2003). Despite the controversy, the adoption of early intervention services is now policy in the UK (Department of Health, 2001). There are few randomised controlled trials of early intervention, and preliminary findings have been reported only for the OPUS study in Denmark (Reference Nordentoft, Jeppesen and AbelNordentoft et al, 2002) and for a small study in south London (Reference Kuipers, Holloway and Rabe-HeskethKuipers et al, 2004). Although people with first episodes of psychosis respond well to initial treatment, they frequently relapse and a substantial proportion of people develop persisting symptoms (Reference Mason, Harrison and GlazebrookMason et al, 1995; Reference Wiersma, Nienhuis and SloofWiersma et al, 1998; Reference Robinson, Woerner and AlverRobinson et al, 1999). Social and functional deterioration is also a marked feature of the early course of the disorder (Reference Wyatt, Green and TumaWyatt et al, 1997; Reference Birchwood, Jackson and ToddBirchwood et al, 1998). In aiming to improve these outcomes, some offer a package of care and interventions especially adapted for people with early psychosis (Reference Cullberg, Levander and HolmqvistCullberg et al, 2002; Reference Nordentoft, Jeppesen and AbelNordentoft et al, 2002; Reference Malla, Norman and McLeanMalla et al, 2003; Reference Kuipers, Holloway and Rabe-HeskethKuipers et al, 2004); other initiatives involve the provision of individual treatments, such as cognitive-behavioural therapy and supportive counselling (Reference Lewis, Tarrier and HaddockLewis et al, 2002; Reference Tarrier, Lewis and HaddockTarrier et al, 2004), or family interventions (Reference Zhang, Wang and LiZhang et al, 1994; Reference Linszen, Dingemans and Van der DoesLinszen et al, 1996). It is therefore important to examine a range of outcomes.

In this study we set out to investigate whether a new community team (the Lambeth Early Onset team), providing a specialist service for people with a non-affective psychosis who present to services for the first time (or second time, if they previously failed to engage in treatment), would achieve better outcomes than existing services. In an earlier study (Reference Craig, Garety and PowerCraig et al, 2004) we found evidence to suggest that the Lambeth Early Onset service achieved superior outcomes in rehospitalisation over 18 months and that participants maintained higher rates of contact with services. Participants were also less likely to relapse; however, when adjusted for baseline imbalances in gender, past episode and ethnicity, this improvement in relapse rate failed to remain statistically significant. The study reported here aimed to test the hypotheses that the intervention would be associated at 18 months with:

-

(a) lower symptoms and improved insight;

-

(b) better adherence to prescribed medication;

-

(c) greater satisfaction with services and quality of life;

-

(d) better social functioning, including occupation, housing and relationships;

-

(e) fewer adverse events, including homelessness, violence and self-harm;

-

(f) lower overall costs of care (to be reported separately).

METHOD

Study design and context

The study was a randomised controlled trial (International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number 73679874). Eligible patients were randomly allocated to care from the early onset team or from a community mental health sector team. The setting, Lambeth, is a socially deprived and ethnically diverse inner-city borough of London. Mental health services for the borough are provided by the South London and Maudsley National Health Service (NHS) Trust.

The experimental service

The Lambeth Early Onset team is a multidisciplinary team comprising one team leader, one part-time consultant (2 sessions), one trainee psychiatrist, a half-time clinical psychologist, one occupational therapist, four community psychiatric nurses and two healthcare assistants. It was established in January 2000 on principles of assertive outreach (Department of Health, 2001), providing a single point of access for all the mental health and social welfare needs of its patients, with an extended-hours service 5 days per week (0.800 h to 20.00 h) and open from 09.00 h to 17.00 h at weekends and public holidays. The interventions provided by the team were specially adapted for a group with early psychosis and followed protocols and manuals from the Early Psychosis Prevention and Intervention Centre (1997) early intervention service (Reference Edwards and McGorryEdwards & McGorry, 2002) and, for cognitive-behavioural therapy, pilot work conducted locally (Reference Jolley, Garety and CraigJolley et al, 2003). A mix of medication management, cognitive-behavioural therapy, vocational input and family interventions was provided according to individual need. The emphasis of the whole programme was on helping the patient retain or recover functional capacity to return to study or work, to resume leisure pursuits and retain or re-establish supportive social networks. A family and carers support group was established, as was a social activity programme open to all patients in the service. Staff were selected who had an interest in working with younger people and who were sensitive to the needs and concerns of the local minority ethnic population.

Comparison services

For the borough of Lambeth, community services at the time were provided through five mental health teams, each providing a range of assessment, treatment and continuing care to a geographically defined sector. Sector teams typically comprised psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists and part-time clinical psychologists. Each of these sector community teams was associated with inpatient facilities on one of three hospital sites. Prior to the establishment of the early onset team, all people presenting with suspected first episodes of psychosis were seen either by the sector community team or the associated in-patient service following referral from the person's general practitioner, through accident and emergency departments of local hospitals, or following contact with another statutory agency (e.g. police or courts). If admitted, the patient was followed up by a sector team on discharge.

The control condition was standard care as delivered by the sector community teams. These teams received no special training or support in the management of early psychosis, although they were not discouraged from following best practice guidelines. Given that the UK government's decision to implement early psychosis services and the publication of implementation guidelines on the management of early psychosis emerged during the life of the study, it is to be expected that all sector teams were attempting best practice within the limitations of generic services.

Participants, recruitment and randomisation

All patients aged 16-40 years with an address in Lambeth and presenting, from January 2000 for an 18-month recruitment period, for the first time with a non-affective psychosis (an ICD-10 diagnosis of F20-29: schizoaffective and delusional disorders; World Health Organization, 1992) were eligible for inclusion. Patients with organic psychosis or with a primary alcohol or drug addiction were excluded. In addition, patients who met these demographic and diagnostic criteria who had presented once previously but had immediately disengaged and were not known to any of the existing mental health services were also deemed eligible. Inability to speak English was not an exclusion criterion, but asylum-seekers who were liable to enforced dispersal were excluded. In order to identify suitable patients, all admissions to hospital and all new referrals to out-patient sector teams were screened over an 18-month period to identify potential cases using a sensitive psychosis screening assessment (Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992). Eligibility for the study was then confirmed by a member of the research team (N.R.), who confirmed symptoms using the Item Group Checklist of the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN; Reference Wing, Barbour and BrughaWing et al, 1990), the likely date of onset of disorder and prior history of contact with psychiatric services, and finally assigned a provisional diagnosis using the Operational Clinical Research Criteria (OPCRIT; Reference McGuffin, Farmer and HarveyMcGuffin et al, 1991) computer program.

Patients who were selected as eligible for the study were then randomly allocated to receive care from the early onset team or from sector community team services using a sequence of sealed, opaque envelopes containing the outcome of randomisation. The latter used randomised permuted blocks of varying block size between two and six. The process of randomisation and allocation was carried out independently of the research or clinical team by the trial statistician (G.D.), based in Manchester. The study was approved by the local research ethics committee and a decision was made to allow randomisation prior to seeking consent and as soon as possible after making initial contact with services. All patients were subsequently informed of the randomisation and written consent was then sought to collect outcome data from case notes and by interview. The rationale and procedure for this are fully described by Craig et al (Reference Craig, Garety and Power2004). In practice, only one patient objected to the randomisation and was therefore treated by the local sector team, although this individual's data were analysed as allocated to the early onset team.

Measures

Standardised assessments by trained independent research staff were administered at baseline within 1 week of randomisation and at 18 months' follow-up.

Baseline assessments

Socio-demographic data were recorded, including age, gender, marital status, accommodation, education and employment. The participants' clinical state, overall functioning and levels of depression were assessed using the following measures.

Clinical state. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS; Reference Kay, Fiszbein and OplerKay et al, 1987) is a 30-item, seven-point rating instrument with sub-scale scores for positive symptoms, negative symptoms, general psychopathology and a total score (total scale range 30-210).

Overall functioning. The Global Assessment of Function (GAF; Reference Endicott, Spitzer and FleissEndicott et al, 1976) is a widely used scale measuring overall functioning during the previous month, on a hypothesised continuum (scored 0-100) between severe psychiatric morbidity and health. It has been shown to have good interrater reliability for use with people with psychosis (Reference Startup, Jackson and BendixStartup et al, 2002).

Depression. The Calgary Depression Rating Scale, a nine-item scale (score range 0-27) designed for rater assessment of symptoms of depression in people with schizophrenia, has been shown to have adequate reliability and validity (Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-TyndaleAddington et al, 1993).

Assessment at 18 months

Clinical measures were repeated as described above. In addition, the following factors were assessed.

Insight and treatment adherence. The Scale for the Assessment of Insight (Reference David, Buchanan and ReedDavid et al, 1992) is a well-established measure of insight, assessed by nine items, six items scored 0-2 and three items scored 0-4, scale range 0-24 (high scores representing good insight). In the Expanded version (SAI-E; Reference Kemp, Kirov and EverittKemp et al, 1998), adherence to medication is assessed by researcher interview using the compliance sub-scale of the SAI-E, resulting in a summary score on a scale of 1-7, where 1 represents ‘complete refusal’ and 7 represents ‘active participation, readily accepts and shows some responsibility for medication regimen’. Adherence was also independently assessed over the entire 18 months from case-note records of prescribing and clinician-assessed adherence: time to first point of non-adherence to prescribed medication was defined as months from baseline to the first month in which it was recorded that the patient had discontinued the medication for any reason.

Satisfaction. The Verona Service Satisfaction Scale (Reference Ruggeri and Dall'AgnolaRuggeri & Dall'Agnola, 1993) ‘professionals’ skills and behaviour' subscale (eight applicable items, scored 1-5, total scale range 8-40) is a self-report Likert scale addressing patients' satisfaction with community-based psychiatric services, with good sensitivity, test-retest reliability and content validity (Reference Ruggeri, Dall'Agnola and AgostiniRuggeri et al, 1994). A separate summary item, ‘belief that the treatment is right for you’, is scored 1-10. The professionals' skills and behaviour sub-scale has been found to make a major contribution to reported satisfaction with services (Reference Ruggeri, Dall'Agnola and AgostiniRuggeri et al, 1994).

Quality of life. The Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA; Reference Priebe, Huxley and KnightPriebe et al, 1999) comprises 12 subjective items on a seven-point rating scale (from ‘couldn't be worse’ to ‘couldn't be better’, scored 1-7, range 12-84), assessing satisfaction with life ‘in general’ and in a range of domains, such as vocational, financial, friendships, leisure, personal safety, physical health and mental health. Four objective items, answered ‘yes’ or ‘no’, assess the existence of a close friend, contacts with friends per week, accusation of a crime and victimisation of physical violence. It has good concurrent validity and internal consistency.

Clinical record data. The patients' clinical state, social functioning, contact with clinical services and uptake of treatment were monitored through their clinical case-note files across the entire 18-month period of the study. Detailed extracts concerning mental state, treatment adherence, service contact and interventions and social functioning were compiled, from which all information that might provide clues as to whether the patient was being seen by the early onset team or receiving standard care had been removed. These records were used to rate recovery and relapse in our earlier study by independent raters, masked to condition, with good interrater reliability (Reference Craig, Garety and PowerCraig et al, 2004), and were used in the same way in this study for rating social recovery cross-sectionally at the 18-month follow-up point, on a three-point scale (‘no’, ‘partial’ and ‘full’) of recovery to baseline levels, in the following areas:

-

(a) Housing: in-patient care, homelessness or prison were rated as ‘no recovery’, sheltered or supported accommodation as ‘partial recovery’ and return to previous independent accommodation (including living with family members) or acquiring new independent accommodation as ‘full recovery’.

-

Vocational or educational status: ‘full recovery’ was rated for return to, or taking up, full-time independent employment or full-time education; ‘partial recovery’ was rated for parttime work or education, or for supported work or activity programmes; ‘no recovery’ was rated for no regular scheduled work or educational activity. The case-note data were also analysed to record total number of months engaged in regular scheduled work or educational activity over the entire 18-month period.

-

Relationships: ‘full recovery’ was rated for return to or establishment of close personal relationships, with a partner or family; ‘partial recovery’ was rated for evidence of some ongoing social contact with friends or family; ‘no recovery’ was rated for no evidence of any regular social relationship or activity.

The interrater reliability for ratings of social recovery was good or excellent (according to conventional evaluation of kappa values; Reference RobsonRobson, 1993) (n=23; housing, k=0.69, P <0.001; vocational k=0.70, P <0.001; relationships, k=0.83, P <0.001).

Adverse incidents. Adverse incidents from NHS trust incident records and case-note data included death, prison, self-harm, violence to others and homelessness.

Assessor masking

The research assistants, although independent of service provision, were not unaware of treatment group allocation; this was impracticable, given that this was a study of the effects of allocation to a whole service. However, the case-note data were rated masked to condition. In order to test the success of the efforts to ensure masking, the two assessors guessed whether each participant had been receiving care from the early onset team or the sector community services. The two raters correctly guessed the allocation of 60% of participants, which is marginally better than chance (95% CI 52-63%, k=0.20). The adverse incident data were recorded and extracted for the whole sample by trust staff masked to treatment condition.

Data analysis

The sample size for the study was calculated on the basis of the estimated reduction in relapse rates (the primary outcome). A total of 120 patients were required to show a reduction of relapses in the experimental condition at 18 months from 60% to 40% of the sample, with a power of 80% at α=0.05. The analysis was done using STATA release 8 (StataCorp, 2003). Intention-to-treat analyses compared the two groups in terms of cross-sectional outcomes at 18 months, with all available participant data in the analysis. First, for all variables except the case-note data and adverse incidents, estimates of intervention effects on the outcome scores were obtained through the use of a regression (analysis of covariance, ANCOVA) using the relevant baseline score as a covariate if assessed; subsequent analyses also entered as covariates ethnicity, gender and whether first or second episode to allow for baseline imbalances in these variables. Finally, the sensitivity of the results to the missing follow-up data was examined by repeating the above regression analyses, but with the additional use of inverse probability weighting (Reference Heyting, Tolbroom and EssersHeyting et al, 1992; Reference Everitt and PicklesEveritt & Pickles, 1999) to adjust for rates of attrition that were dependent on both treatment group and selected baseline covariates. The weights were determined (for each randomised group separately) using a logistic regression to predict missing PANSS values, using ethnic group, gender, number of previous episodes, contact with family and having a stable relationship as predictors (the weight being the reciprocal of the predicted probability of having a non-missing outcome measure). The clinical record data outcomes, with low levels of missing data, were analysed for group differences at 18 months by w2 tests or t-tests. A Cox's proportional hazards model was used to test the association between non-adherence to prescribed medication and group membership, ethnicity, gender and whether first episode.

RESULTS

Participant recruitment and follow-up

Over the 18-month study period 144 persons who met inclusion criteria presented and were randomly allocated to either the early onset team or the sector community team (Fig. 1). Data on the primary outcomes of relapse and rehospitalisation were obtained on 135 (94%) of these patients over the 18-month follow-up (Reference Craig, Garety and PowerCraig et al, 2004) and for 132 patients (92%: intervention group 94%, standard care group 89%) we had case-note records from which information was drawn on social outcomes (housing, vocational activity and relationships), medication adherence and adverse events at the 18-month follow-up point. A rather lower proportion of eligible patients consented to and completed the research interview for the other outcomes at 18 months: n=99 (69%); intervention group n=55 (77%), standard care group n=44 (60%). The reasons for non-completion of data collection are shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 Flow of participants through study.

Sample characteristics

As would be expected of an early psychosis population, the majority of the sample were male (65%) and single (70%), and the average age was 26 years. More than half were from a minority ethnic, predominantly of African or Caribbean parentage. Over half were unemployed (62%). The majority met ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia (69%). Experimental and control groups were similar for all characteristics, including the duration of untreated psychosis, except that the intervention group had significantly fewer males (intervention group 55% v. control group 74%), a higher proportion of first-ever episode (86% v. 72%) and a higher proportion of White ethnicity (38% v. 25%). A more detailed description of the sample is given by Craig et al (Reference Craig, Garety and Power2004).

Clinical outcomes, satisfaction and social outcomes

The summary data for the clinical measures (PANSS, GAF and Calgary Depression Scale) at baseline and at 18 months are given in Table 1. Comparisons were made between groups on the scores for these measures by means of separate ANCOVAs, first with baseline score as a covariate, then entering ethnicity, gender and whether first or second episode as covariates. The estimated intervention effects are shown in Table 2. There was a trend for an effect of the intervention on PANSS total scores, largely attributable to a significant effect on PANSS negative symptoms in the first analysis; however, this effect becomes non-significant when adjusting for differences in other baseline variables. There is no effect on the Calgary Depression Scale. There are consistently significant effects on the GAF favouring the intervention group.

Table 1 Clinical symptom assessments at baseline and at 18 months

| Intervention group | Control group | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 18 months | Baseline | 18 months | |||||||||||

| n | Score Mean (s.d.) | n | Score Mean (s.d.) | n | Score Mean (s.d.) | n | Score Mean (s.d.) | |||||||

| PANSS | 56 | 55 | 43 | 44 | ||||||||||

| Total | 67.4 (17.2) | 51.2 (15.2) | 73.3 (19.7) | 58.9 (14.2) | ||||||||||

| Positive symptoms | 17.2 (6.2) | 11.8 (5.1) | 18.9 (6.4) | 14.0 (5.9) | ||||||||||

| Negative symptoms | 15.1 (7.0) | 11.9 (5.1) | 17.8 (12.7) | 14.8 (5.4) | ||||||||||

| General | 35.0 (7.7) | 27.4 (7.6) | 36.6 (8.1) | 30.2 (7.0) | ||||||||||

| GAF | 56 | 46.5 (15.3) | 54 | 64.1 (15.3) | 43 | 42.2 (14.8) | 44 | 55.3 (15.1) | ||||||

| Calgary Depression Scale | 56 | 4.1 (3.5) | 55 | 2.7 (3.3) | 43 | 3.3 (3.2) | 44 | 2.7 (3.5) | ||||||

GAF, Global Assessment of Function; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Table 2 Clinical symptoms: estimated treatment effects at 18 months

| Intervention effect | Adjusted for ethnicity, gender and episode | With inverse probability weights | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P | Coefficient (95% CI) | P | Coefficient (95% CI) | P | ||||

| PANSS | |||||||||

| Total | 5.74(−0.30 to 11.79) | 0.06 | 5.26(−1.14 to 11.65) | 0.11 | 4.90(−0.96 to 10.76) | 0.10 | |||

| Positive symptoms | 1.32(−1.01 to 3.65) | 0.26 | 1.42(−1.07 to 3.91) | 0.26 | 1.42(−0.73 to 3.56) | 0.19 | |||

| Negative symptoms | 2.30(0.02 to 4.57) | 0.048 * | 1.62(−0.78 to 4.02) | 0.18 | 1.41(−0.97 to 3.79) | 0.24 | |||

| General | 2.19(−0.75 to 5.13) | 0.14 | 2.14(−0.97 to 5.25) | 0.17 | 1.97(−0.87 to 4.82) | 0.17 | |||

| GAF | −8.72(15.46 to −1.98) | 0.01 * | −8.77(−15.89 to −1.65) | 0.02 * | −8.38(−15.61 to −1.16) | 0.02 * | |||

| Calgary Depression Scale | 0.93(−0.47 to 2.33) | 0.19 | 0.98(−0.51 to 2.47) | 0.19 | 0.82(−0.62 to 2.36) | 0.25 | |||

GAF, Global Assessment of Function; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

* P<0.05.

Data for insight, satisfaction, quality of life and interview-rated treatment adherence at 18 months are given in Table 3. Comparisons were made between groups for intervention effects using ANCOVAs, with a second analysis entering ethnicity, gender and whether first or second episode as additional covariates (Table 4). There is no effect on insight; however, there is a just-significant effect on treatment adherence and consistently significant effects on service user satisfaction and self-rated quality of life, all favouring the intervention group. Inspection of individual items reveals that the significant differences on the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale were attributable to satisfaction with the manners of staff, the perceived competence of staff, staff willingness to listen, satisfaction with the type of service offered, and the separate summary item: belief that the treatment ‘is right for me’ (P <0.01). On the MANSA, individual subjective items reported by the intervention group as of better quality (P <0.10) were life in general, accommodation, people that you live with, relationship with family, physical health and mental health. The objective items (existence of a close friend, contacts with friends per week, accusation of a crime and victimisation of physical violence) did not differ between the groups.

Table 3 Insight and adherence at baseline and 18 months, and satisfaction and quality of life at 18 months

| Measure | Intervention group | Control group | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 18 months | Baseline | 18 months | |||||||||||

| n | Mean (s.d.) | n | Mean (s.d.) | n | Mean (s.d.) | n | Mean (s.d.) | |||||||

| Insight 1 | 55 | 11.4 (6.9) | 54 | 16.6 (7.2) | 41 | 9.8 (5.7) | 43 | 12.7 (7.7) | ||||||

| Adherence 2 | 55 | 4.9 (1.5) | 49 | 5.4 (1.4) | 40 | 5.0 (1.3) | 41 | 4.5 (1.8) | ||||||

| Satisfaction 3 | 50 | 13.9 (4.8) | 44 | 17.1 (5.9) | ||||||||||

| Quality of life 4 | 52 | 59.2 (12.6) | 40 | 53.3 (12.4) | ||||||||||

1. Scored on the Scale for Assessment of Insight - Expanded (SAI-E); higher scores represent better insight.

Table 4 Insight, adherence, satisfaction and quality of life: estimated treatment effects at 18 months

| Measure 1 | Intervention effect | Adjusted for ethnicity, gender and episode | With inverse probability weights | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% Cl) | P | Coefficient (95% Cl) | P | Coefficient (95% Cl) | P | ||||

| Insight | −2.94 (−6.20 to 0.31) | 0.076 | −2.45 (−5.94 to 1.05) | 0.167 | −3.03 (−6.91 to 0.86) | 0.125 | |||

| Adherence | −0.76 (−1.45 to −0.06) | 0.033* | −0.74 (−1.49 to 0.02) | 0.055 | −1.00 (−1.93 to −0.07) | 0.036* | |||

| Satisfaction | 3.19 (1.00 to 5.37) | 0.005** | 2.98 (0.62 to 5.33) | 0.014* | 1.57 (−0.97 to 4.10) | 0.223 | |||

| Quality of life | −5.96 (−11.19 to −0.74) | 0.026* | −7.08 (−12.47 to −1.69) | 0.011* | −6.60 (−11.59 to −1.61) | 0.010* | |||

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01.

1. See footnotes to Table 3.

2. Scored on the SAI-E compliance sub-scale; higher scores represent better adherence.

3. Scored on the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale.

4. Scored on the Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life; higher scores represent better quality of life.

The analyses were then repeated allowing for the same baseline covariates, but with additional adjustments provided using inverse probability weights to allow for non-random patterns of missing data (see Tables 2 and 4). For the most part, these showed few differences from the results after adjustment for the baseline differences in ethnicity, gender and episode (the second sets of analyses). However, the effect on the Verona Service Satisfaction Scale is no longer significant.

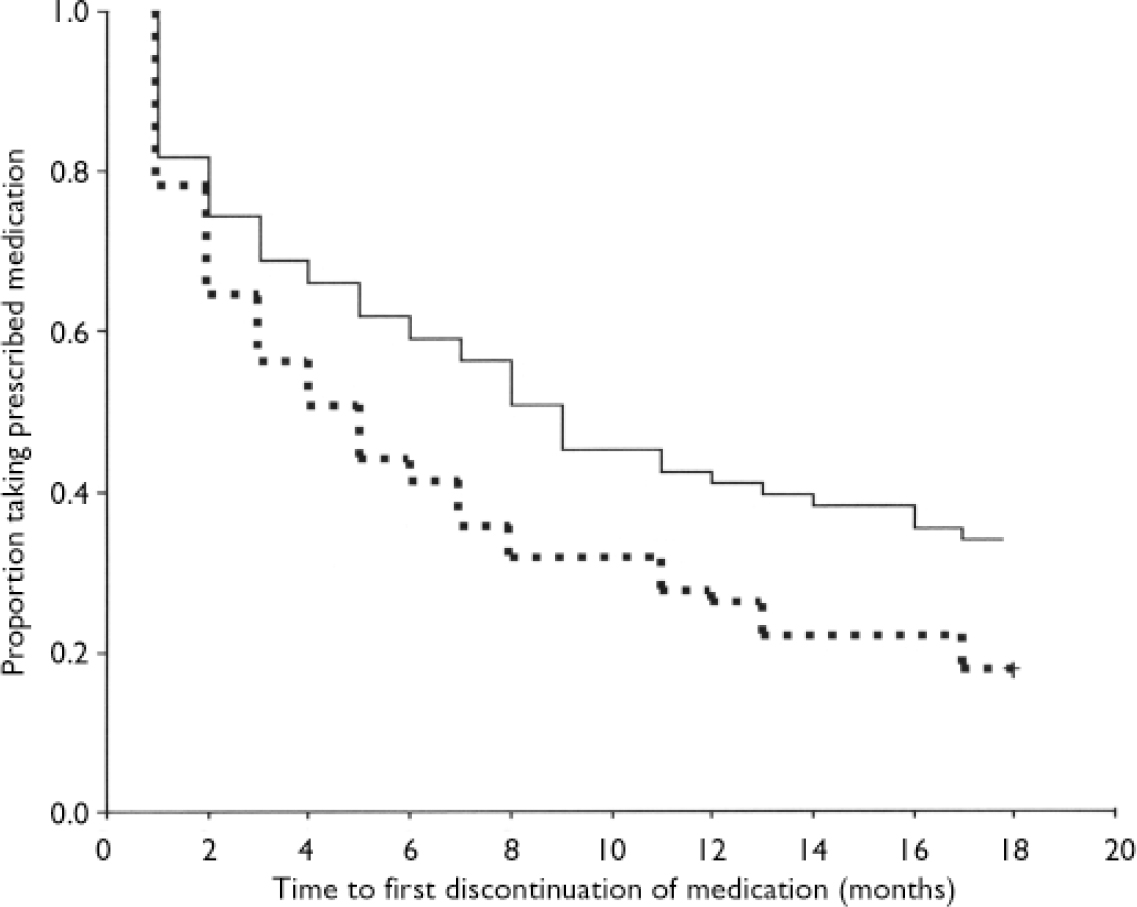

The number of months for which the groups maintained adherence to prescribed medication was entered into a survival analysis (Fig. 2). A Cox's regression analysis showed that the groups differed significantly: the hazard ratio for the risk of discontinuing medication for a person in the control group was 1.5 times that of a person in the intervention group (n=131, hazard ratio 1.5, 95% CI 1.05-2.2; P=0.029). Half of the intervention group had first discontinued medication for any reason by 9 months, whereas half of the control group had first stopped taking medication by 5 months (Fig. 2). There was a slightly higher proportion of those who discontinued medication against medical advice at least once over the entire 18 months, as documented in the case notes, in the control group (95%; 57/60) compared with the intervention group (79%; 37/47).

Fig. 2 Adherence to prescribed medication over 18 months (survival analysis): solid line, intervention group; dashed line, standard care group.

The social outcomes (housing, vocational activity and relationships) at 18 months are shown in Table 5. Comparisons of full recovery with combined partial and no recovery are made between the groups using χ2 tests. Although housing and vocational/educational outcomes do not significantly differ between groups, relationships outcomes are significantly better in the intervention group.

Tabel 5 Social recovery: housing, vocational activity and relationships at 18 months (full recovery v. partial and no recovery)

| Intervention group: full recovery % (n/N) | Control group: full recovery % (n/N) | χ2 | d.f. | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Housing | 70 (46/66) | 58 (36/62) | 1.879 | 1 | 0.170 |

| Vocational/educational | 33 (21/64) | 21 (13/61) | 2.086 | 1 | 0.149 |

| Relationships | 55 (34/62) | 25 (14/57) | 11.31 | 1 | <0.001 |

Any vocational and educational activity in a given month across the 18-month period, as recorded in the case notes, was also analysed. The intervention group was engaged in an activity for significantly more months (6.9 months, s.d.=6.6; n=67) than the control group (4.2 months, s.d.=5.3; n=65); t=2.689, P=0.008. This advantage for the intervention was also apparent when comparing the groups in terms of those who had spent 6 months or more engaged in an educational or vocational activity: intervention group 49% (33/67), control group 29% (19/65); χ2=5.54, d.f.=1, P=0.019.

Adverse events and homelessness

At 18 months, one participant receiving standard care had died of unknown cause and another was in prison. Adverse incident records from the clinical services (in-patient and community) over the 18-month study period were examined. These revealed that 12 members of the early onset team group (17%) and 14 of the control group (19%) were recorded as involved in a violent act towards a member of staff; 14 of the intervention group (20%) and 15 of the control group (20%) were violent towards another patient or a member of the public. Six of the intervention group (8%) and 5 of the control group (7%) were recorded as having engaged in self-harm, such as taking an overdose. In terms of homelessness, from case-note records and researcher enquiries, at 18 months, 1 participant from the intervention group and 2 from the control group were homeless, and the whereabouts of 5 (7%) and 10 (14%) control participants could not be ascertained. In terms of housing, 5 (7%) intervention group members and 2 (3%) of the control group were in supported accommodation, 59 (83%) of the intervention group and 54 (74%) of the control group were in independent accommodation or residing with family, and 1 of the intervention group and 3 of the control group were in ‘other’ (e.g. shared housing).

DISCUSSION

Benefits of early intervention

This study is one of the first UK randomised controlled trials to report the effects of an early intervention service, and, indeed, is one of very few worldwide. It provides support for the current government policy of developing such services. It is not only in the UK that this is relevant; many other countries, including Canada, Australia, Denmark and Norway, are engaged in similar programmes to establish early intervention services. The results indicate that the provision of a specialist service for people early in the course of psychosis has a range of benefits: at 18 months it has superior social outcomes, in regaining or establishing social relationships, in time spent in vocational activity and in global functioning; it is more satisfactory to participants than generic sector services, and leads to a higher reported quality of life. It also improves observer-rated and casenote records of adherence to medication. These are in addition to the previously reported benefits of increased contact with services and reduction in hospitalisation (Reference Craig, Garety and PowerCraig et al, 2004). There were fewer recorded incidents of most categories of adverse events in the Lambeth Early Onset team group (death, prison, homelessness and violence - but not self-harm), although these are relatively rare events for the whole sample and do not differ significantly. The recorded incidence of self-harm over 18 months in 7.6% of the whole sample is somewhat lower than that reported in the only comparable study, by Nordentoft et al (Reference Nordentoft, Jeppesen and Abel2002), who reported that 11.3% of their first-episode sample engaged in self-harm over a 1-year follow-up period. (We do not, however, conclude that this reflects a particularly low rate in the current study. The definitions and data collection methods were not identical in the two studies and we consider that our data may be susceptible to underreporting, especially in the control group, more of whom were out of contact with services.) For some variables - vocational activity and medication adherence - the results offer clearer support for the effects of early onset team care when using data drawn from the entire 18-month period than cross-sectionally at 18 months. This may, in part, reflect the larger sample size included, especially for the control group, when using case-note data rather than data obtained from researcher interviews.

Symptoms

Despite the benefits described above, it appears that the specialist early onset service does not specifically improve persisting symptoms. As would be expected, given that the initial assessments were made in the acute episode of illness and the follow-up was 18 months later, symptoms did improve substantially over time in both groups. However, contrary to our hypothesis, allocation to the early onset team service had few significant effects on symptoms, with no effect on positive psychotic symptoms or general psychopathology and no improvement on a scale of depression. There is some evidence of benefits for negative symptoms; however, when adjustments are made for chance baseline differences and to account for missing data, the difference is no longer significant. Insight also was not significantly improved. Given the evidence for the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural therapy in reducing persisting symptoms (Reference Pilling, Bebbington and KuipersPilling et al, 2002) and the promising findings from the Study of Cognitive Reality Alignment Therapy in Early Schizophrenia (SoCRATES) trial of psychological treatments in early psychosis (Reference Tarrier, Lewis and HaddockTarrier et al, 2004), it is not clear why early onset team care, which included cognitive-behavioural therapy, did not result in greater symptomatic improvements. The early onset service delivered interventions in a pragmatic mix, according to patient preference and identified need. These interventions were also provided in the control teams, although at a lower rate (Reference Craig, Garety and PowerCraig et al, 2004). It may be that a more systematic approach to the provision of cognitive-behavioural therapy should be attempted in early intervention services, ensuring that all who are willing to receive this therapy have a reasonable number of sessions (at least ten; National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002) and especially targeting those with persisting symptoms (Reference Jolley, Garety and CraigJolley et al, 2003).

Range of outcomes

A strength of this study is that it provides data on a range of outcomes. Studies of clinical interventions or services for people with psychosis are often criticised for providing only clinical data on relapses, readmission and symptoms (National Institute for Clinical Excellence, 2002). We report, in addition, service user satisfaction data, quality of life and a range of social outcomes, and adverse events. The satisfaction and quality of life data are encouraging, in that they suggest that service users with early psychosis in general find the provision of a service with active outreach acceptable. It is also noteworthy that major adverse events were certainly not increased, if not significantly less frequent, in the intervention group. Of course, this study does not tell us how the improvements occurred; it was not designed or powered to test hypotheses concerning mediators of treatment outcomes. It is possible that key factors resulting in reductions in relapse and rehospitalisation were the maintenance of contact with service users and continuance of medication. It is perhaps less plausible to attribute the social and vocational benefits to these variables alone; we suggest that the team's explicit focus on work in these areas was important. Given the importance of employment in assisting in the long-term recovery from schizophrenia (Reference WarnerWarner, 1994) and the beneficial role of protective social relationships (e.g. Reference Jablensky, Sartorius and ErnbergJablensky et al, 1992), this study adds to the literature by demonstrating it is possible to intervene to improve these factors by offering an early psychosis service.

Limitations of the study

The study had a number of methodological limitations. The sample size was designed to be adequate for the primary outcome of relapse, but proved somewhat underpowered for the adjustments required by chance baseline differences in variables likely to affect outcome. Another methodological concern was follow-up rates. We had previously discovered that there was a high rate of disengagement and loss to clinical follow-up from existing services in this early psychosis group within the Lambeth inner-city area (Reference Garety and RiggGarety & Rigg, 2001). Thus, although one strength of the study was its inclusion of all first episodes from a defined geographical area, enhancing the generalisability of our findings, this strategy paradoxically also led to a substantial limitation as it necessarily increased the inclusion of substantial numbers of patients who would traditionally fail to engage with treatment or agree to participate in detailed follow-up interviews. We anticipated that this might prove a problem as it has also been reported in other studies (e.g. Reference Kemp, Kirov and EverittKemp et al, 1998) and might also result in differential attrition between groups, given that the Lambeth Early Onset service was aiming explicitly to improve rates of contact. This proved to be the case despite vigorous attempts at follow-up. To deal with this, in order to reduce sole reliance on face-to-face contacts, case notes and other routinely collected clinical records (e.g. adverse incidents) were used, where possible, to provide data for some of our secondary outcomes. Where reliance on face-to-face research interviews was necessary, for example for clinical symptom assessments and service user satisfaction, we employed statistical techniques to test for the sensitivity of the results to the non-randomness of missing data. Not being in a stable relationship and not having contact with family members at baseline predicted missing data at 18 months. In general the results were not changed by the sensitivity tests; however, there was an effect on the satisfaction results, which suggests that the satisfaction data should be treated with some caution. A third limitation is that the research assessors were not masked to condition. Trials with inadequate allocation concealment have been shown to report larger treatment effects than those in which concealment has been achieved (Reference Schulz, Chalmers and HayesSchulz et al, 1995). Given that this was a trial of allocation to a complete service, rather than a study of a discrete and time-limited intervention, masking was not possible, since it was not possible (or safe) to contact participants totally independently of the clinical service. The outcomes reported in this study are, however, not restricted to assessor ratings. Finally, this is a study of a new team from its inception. None of the original team had prior experience in early intervention. As has been noted, this team was learning on the job and developing skills as the study progressed (Reference SinghSingh, 2005). This may have limited the capacity of the clinicians in this new team to deliver the most effective mix of interventions.

The Lambeth Early Onset trial adds to the evidence base by demonstrating that a newly formed specialist early intervention team achieved improved outcomes at 18 months in a number of different outcome domains, when compared with the provision of services by generic teams. It would clearly be of interest to examine the effects of this service over a longer follow-up period and also to compare the effects of a specialist team with the provision of phase-specific interventions delivered by a different service model, such as specialist workers within generic teams. However, this study does provide support for the current UK policy on early intervention.

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ Social and clinical outcomes in early psychosis can be improved by the provision of an assertive outreach team offering a package of evidence-based treatments and care.

-

▪ Service users report a better quality of life and greater satisfaction with an early intervention service than with generic sector teams.

-

▪ A systematic approach to monitoring and preventing the early development of persisting psychotic symptoms should be taken.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ The study was somewhat underpowered when adjustments were made for chance imbalances in baseline variables.

-

▪ For some outcomes, sample attrition reduced the sample size, par particularly in the control group.

-

▪ Research assessors were aware of treatment condition for some outcome variables.

Acknowledgements

The study was funded by a grant from the Directorate of Health and Social Care for London R&D Organisation and Management Programme. The research team is entirely independent of the funders. T.C. and P.P. have received support from Eli Lilly, AstraZeneca, Janssen-Cilag and Novartis for attending and speaking at conferences.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.