Introduction

Self-practice/self-reflection

Self-practice/self-reflection (SP/SR) is an evidenced therapist training methodology that has been used extensively within cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) training and professional development (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003). It has been defined as ‘a formal self-experiential training process over an extended period of time, following through on real-life issues and developing reflective skills as a bridge between personal impact of the therapeutic techniques and implications for the therapist role’ (Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019; p. 383). Therefore, SP/SR can be seen as an integrative methodology, that falls somewhere in the intersection between more traditional forms of CBT training (for example, didactic teaching or role-plays) and types of personal practice (for example, personal therapy or meditation; Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019; Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018; Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019; Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014). Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff (Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019) provide a helpful overview of SP/SR.

SP/SR is underpinned by a model of therapist skill development, known as the declarative-procedural-reflective (DPR) model, which was developed in parallel by Bennett-Levy (Reference Bennett-Levy2006). This model proposes three systems: a declarative system (involved in the ‘what’ of therapy, for example, conceptual and technical knowledge), a procedural system (involved in the ‘how’ and ‘when’ of therapy, where declarative knowledge is applied in practice) and a reflective system (the ‘engine’ of skill development, involved in the evaluation of declarative knowledge and procedural skills, supporting the refinement and development of skills; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Chaddock, Davis, Dallos and Stedmon2009b). The DPR model also distinguishes between the personal self and the therapist self, which are seen to be distinct but overlapping, and influence skill development (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff, Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019). Therefore, SP/SR as a methodology is seen to work across these three systems in developing therapist skills, where the experiential and reflective elements are seen to be particularly key in developing procedural and reflective skills (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, McManus, Westling and Fennell2009a). The DPR model has also been extended to describe a personal practice (PP) model, which outlines how SP/SR and other forms of personal practice are related to therapist skilfulness (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018). A key addition in the PP model is the emphasis on a ‘reflective bridge’, which serves as a link between personal self-reflection and therapist self-reflection, and the process of transitioning between the two has possible outcomes such as enhanced self-awareness, personal development, and enhanced reflective and conceptual/technical and interpersonal beliefs and skills (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018).

To date, a number of research studies have evaluated the impact and experience of participating in formal SP/SR programmes. Declarative, procedural and reflective skill development has been found to be one of the primary outcomes of SP/SR (Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014), such as improvements in the understanding of the CBT model (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001; Haarhoff et al., Reference Haarhoff, Gibson and Flett2011), improvements in specific technical skills (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Davis et al., Reference Davis, Thwaites, Freeston and Bennett-Levy2014), and enhanced interpersonal skills (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Thwaites, Freeston and Bennett-Levy2014; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Cairns, Lowrie, Robinson, Haarhoff, Lockhart and Perry2017). Studies and reviews have also reported outcomes related to personal and professional development, where greater self-awareness is noted and SP/SR is also seen as an effective tool for personal change (Chigwedere et al., Reference Chigwedere, Bennett-Levy, Fitzmaurice and Donohoe2021; Fraser and Wilson, Reference Fraser and Wilson2010; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Yap, Bunch, Haarhoff, Perry and Bennett-Levy2020). These findings have contributed to more recent conceptualisations of SP/SR as a wellbeing intervention, where greater wellbeing and reduced levels of burnout are reported (Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Thwaites, Haarhoff and Perry2015a; Bennett-Levy et al., Reference Bennett-Levy, Wilson, Nelson, Rotumah, Ryan, Budden, Stirling and Beale2015b; Pakenham, Reference Pakenham2015; Scott et al., Reference Scott, Yap, Bunch, Haarhoff, Perry and Bennett-Levy2020). However, some individuals have been found to experience differential levels of benefit from SP/SR, with some people experiencing negative effects (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014; Gale and Schröder, Reference Gale and Schröder2014). In addition, the research base around SP/SR is dominated by qualitative studies, with a need for greater, and more robust, quantitative evaluation (Haarhoff and Farrand, Reference Haarhoff, Farrand, Dryden and Branch2012; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014).

Cultural competence

Despite the growing use of SP/SR in relation to the development of a range of generic and CBT-specific skills, to the authors’ knowledge, there is no existing SP/SR programme that has explicitly addressed the development of therapists’ cultural competence. However, cultural competence and the provision of culturally responsive CBT are regarded as key competencies for CBT practitioners in the UK, as set out by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP) Core Curriculum and Minimum Training Standards for practitioners (British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2021; British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies, 2022). This is also highlighted in several recommended practice guidelines, such as the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Service User Positive Practice Guide (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Naz, Brooks and Jankowska2019). The provision of culturally competent and responsive CBT is a critical issue within CBT practice, where the acceptability of the approach to people from minoritised ethnic backgrounds has been called into question, given its Eurocentric underpinnings and research base (Hays, Reference Hays, Iwamasa and Hays2019; Hays and Iwamasa, Reference Hays and Iwamasa2006; Naeem, Reference Naeem2019; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Kingdon, Pinninti, Turkington and Phiri2015; Rathod et al., Reference Rathod, Phiri and Naeem2019). Furthermore, there are significant issues around access to services, and systemic and structural barriers to care, particularly within the UK’s Talking Therapies programme (previously known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies), which is the main provider of psychological therapies and for which CBT is the predominant approach (Baker, Reference Baker2018; Baker and Kirk-Wade, Reference Baker and Kirk-Wade2023; Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019; Harwood et al., Reference Harwood, Rhead, Chui, Bakolis, Connor, Gazard, Hall, MacCrimmon, Rimes, Woodhead and Hatch2021; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021; Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). There is a clear call from service users and practitioners for CBT provision in the UK to more explicitly consider ethnicity and culture within therapy (Faheem, Reference Faheem2023a; Faheem, Reference Faheem2023b; Jameel et al., Reference Jameel, Munivenkatappa, Arumugham and Thennarasu2022; Mir et al., Reference Mir, Ghani, Meer and Hussain2019; Prajapati and Liebling, Reference Prajapati and Liebling2022).

However, some key issues are highlighted within the CBT and wider cultural competence literature: first, despite the inclusion of cultural competence within CBT training standards, it is unclear how this is translated into teaching and implemented across training courses (Bassey and Melluish, Reference Bassey and Melluish2012). Secondly, there is a significant training gap that is reported by practitioners, where they suggest that professional training courses do not sufficiently address the development of cultural competence (Bassey and Melluish, Reference Bassey and Melluish2012; Benuto et al., Reference Benuto, Singer, Newlands and Casas2019; Faheem, Reference Faheem2023b; Hakim et al., Reference Hakim, Thompson and Coleman-Oluwabusola2019). It is further emphasised that initiatives that seek to develop cultural competence focus more greatly on developing cultural knowledge, with self-reflection and skill development often neglected (Bassey and Melluish, Reference Bassey and Melluish2012; Benuto et al., Reference Benuto, Singer, Newlands and Casas2019; Faheem, Reference Faheem2023a; Haque et al., Reference Haque, Thapa and Kunorubwe2021; Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019). A third identified issue is the overwhelming focus of the cultural competence literature on the practice of White clinicians working with service users from minoritised ethnicities. Therefore, the unique training needs and experiences of therapists from minoritised ethnicities are often left out, despite there being a clearly articulated desire from therapists for their own ethnicity to be considered within their practice (Faheem, Reference Faheem2023a; Faheem, Reference Faheem2023b; Haque et al., Reference Haque, Thapa and Kunorubwe2021; Kadaba et al., Reference Kadaba, Chow and Briscoe-Smith2022; Sue and Sue, Reference Sue and Sue2015).

SP/SR for therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds

A recent theoretical paper by Churchard (Reference Churchard2022) has explored what the application of the DPR model to the development of cultural competence skills in White therapists could look like, including the barriers to skill development, as well as areas for remedial action. However, this has not yet been extended to therapists who are from minoritised ethnic backgrounds. The general success of the SP/SR methodology in developing therapist skills, in particular procedural and reflective skills, may lend itself well to the development of cultural competence. For example, practising culturally responsive CBT techniques on oneself through self-practice (like completing a CBT formulation with the explicit consideration of ethnic identity or identifying strengths associated with ethnic identity), and then subsequently working through reflective questions on the experience and its implications for clinical practice (like how and when it may be incorporated into therapy) may support therapists to develop their skills in this area. Therefore, it is possible that the mechanisms that underlie how more general skills are developed through SP/SR (like conceptual knowledge, procedural skills, interpersonal and reflective skills), as explained by the DPR and PP models, may also support the development of skills in working with ethnicity within clinical practice. In addition, the explicit bridging of the personal and therapist selves may offer therapists from minoritised ethnicities a unique opportunity to explore the personal and professional impact of their ethnicity and to develop a positive sense of their ethnic identity (for example, through developing a timeline of their relationship with their ethnic identity or identifying strengths associated with their own ethnic identity). A positive ethnic identity is understood to be a likely protective factor for ethnically minoritised individuals against the impacts of racism (Chang, Reference Chang2022; Neblett Jr et al., Reference Neblett, Rivas-Drake and Umaña-Taylor2012; Williams et al., Reference Williams, Kanter, Peña, Ching and Oshin2020a; Williams et al., Reference Williams2020b, Williams et al., Reference Williams, Holmes, Zare, Haeny and Faber2022; Umaña-Taylor, Reference Umaña-Taylor, Schwartz, Luyckx and Vignoles2011). Therefore, such a programme may support both the ethnic identity development and wellbeing of therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds.

A novel SP/SR programme for CBT therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds was recently developed with the aim of providing therapists with a supportive space to explore their ethnic identity and its impact on their practice, as well as to develop their skills in working with ethnicity (Churchard and Thwaites, Reference Churchard and Thwaites2022). A full description of the programme and its delivery is provided in the Method section of this paper. The aim of this empirical paper was to quantitatively evaluate this SP/SR programme, using a multiple baselines single case experimental design.

The primary aims of the evaluation were to explore the impact of the programme on:

-

(1) Therapists’ self-rated skill in working with ethnicity within their clinical practice.

-

(2) The ethnic identity development of therapists themselves, particularly around the exploration, resolution and affect associated with their ethnic identities.

-

(3) The wellbeing of therapists in relation to their professional and personal selves.

A secondary aim was to consider if any impacts were maintained following the completion of the programme.

This research was largely exploratory, as it was a novel adaptation of SP/SR. However, given the existing literature, it was hypothesised that the intervention would have positive impacts on skill development, ethnic identity development and wellbeing.

This quantitative evaluation was carried out alongside a qualitative evaluation of participants’ experiences of the SP/SR programme and the implications of the programme on their ethnic and cultural identity (Malik, Reference Malik2024).

Method

Participants

Participants were qualified CBT therapists who self-identified as being from a minoritised ethnic background. This referred to all ethnic groups other than the White British group, so therapists from minoritised White ethnic groups such as Roma and Irish Travellers also met the criteria for participation in the programme (The Law Society, 2023).

Nine participants began the programme in May 2022. The group was ethnically diverse and consisted of seven female and two male therapists. They also ranged in the number of years that they had worked as a qualified CBT therapist, from 2 months to 12 years (as shown in Table 1).

Table 1. Breakdown of participant demographic and contextual information

In addition to demographic information, participants also provided contextual information as to the diversity of the staff teams and service users they worked with, as well as experiences of racism and discrimination in the workplace. As can be seen in Table 1, most participants answered that the staff teams they worked within were ‘A little diverse’. In contrast, there was more of a range within the diversity of service user groups participants worked with, where most participants stated they were ‘Moderately diverse’ to ‘Very diverse’. Of note, almost all participants reported experiences of racism and racial microaggressions within their current workplaces and in therapeutic work with service users.

Of the nine participants who commenced the programme, two dropped out and a third participant did not complete it due to health issues. The outcomes of the six participants who completed the full programme and related evaluations are presented here. Reasons for drop-out were not explored as a part of the current study. However, eight of the participants took part in qualitative interviews at the end of the study. Therefore, the experiences of participants, including participants who dropped out, will be explored as a part of the qualitative evaluation of the SP/SR programme (Malik, Reference Malik2024).

The current SP/SR programme

This SP/SR programme (Churchard and Thwaites, Reference Churchard and Thwaites2022) was developed specifically for CBT therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds with the aim that it would offer therapists a safe and supportive space to explore their ethnic identity and consider its personal impact, as well as any implications on their clinical practice. Therefore, it was hoped that the programme would support therapists to develop a positive sense of their own ethnic identity, while also supporting them to develop their skills in working with ethnicity within their practice, particularly with service users who are also from minoritised ethnic backgrounds.

The programme adopted a CBT approach to support participants to explore their own ethnic background, placing a particular emphasis on strengths associated with ethnic identity, while also recognising and addressing challenges and experiences of racism and discrimination. In addition to the work of Bennett-Levy et al. (Reference Bennett-Levy, Turner, Beaty, Smith, Paterson and Farmer2001, Reference Bennett-Levy, Lee, Travers, Pohlman and Hamernik2003) on SP/SR, which underpinned the programme, it also drew on recent advances in CBT for ethnically diverse populations and anti-racist practice, including the work of Beck (Reference Beck2016), Graham et al. (Reference Graham, Sorenson and Hayes-Skelton2013), Williams (Reference Williams2020), and Sue and colleagues (Reference Sue, Sue, Neville and Smith2019). An expert reference group of three CBT therapists/clinical psychologists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds were also consulted on the programme and evaluation materials.

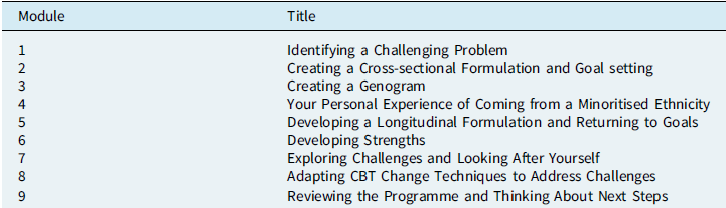

The programme consisted of a workbook with nine modules, which guided participants through a series of self-practice tasks and related self-reflection questions (as shown in Table 2). Participants were also invited to join a facilitated group reflective session every fortnight, on completion of each module. Examples of the self-practice tasks included the completion of a cultural genogram, creating an ethnic identity timeline, and developing a longitudinal formulation around being from a minoritised ethnic background and its influence on participants as therapists. The related self-reflection questions encouraged participants to reflect on the process of completing these tasks and exercises, the impacts on them personally, and crucially, any implications on their clinical practice.

Table 2. SP/SR programme modules

Due to the sensitive content of the programme and evaluations, participants were encouraged to create safety plans at the beginning of the programme and were invited to contact programme facilitators in case of any concerns.

As an example of the programme content, Modules 1 and 6 of the programme are included in Supplementary Material (section A).

Design

An ABC multiple baseline single case experimental design (SCED) was chosen. Data were collected across three experimental phases: baseline (A), SP/SR (B) and follow-up (C) phases. Outcome data were collected weekly and a minimum of three data points per phase was deemed acceptable for inclusion in this study (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010; Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2013; Lobo et al., Reference Lobo, Moeyaert, Cunha and Babik2017).

As there need to be at least three demonstrations of an effect within a SCED, three baseline conditions were chosen which varied in lengths: 7, 6 and 5 weeks (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010; Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2013). Participants were randomly allocated to these three baseline conditions, with three participants in each condition (as shown in Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Participant allocation and attrition diagram.

Measures

Outcomes were considered in relation to three main areas: therapist skill in working with ethnicity, ethnic identity development, and wellbeing. They were completed by participants weekly, via an online survey tool. Due to the frequency of data collection, the aim was for outcome measures to be brief and easy to complete, therefore measures were either developed or adapted for this evaluation. Each outcome item was evaluated separately. For all measures, higher self-ratings were associated with improved outcomes.

The outcome questionnaire is included in the Supplementary material (section B).

Therapist skill in working with ethnic identity

A set of 10 skill-related outcomes were developed. These skill outcomes largely related to procedural and reflective skills as set out by the DPR model (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006) and were informed by ideas around the provision of effective transcultural CBT (Beck, Reference Beck2016).

These outcomes broadly related to technical skills, such as skills in exploring ethnicity and including this within formulations, reflective skills, such as skills in managing personal resonances and addressing ethnic similarities and differences with clients, and supervision skills, such as the skills to bring discussions related to ethnicity within one’s own supervision or as a supervisor.

Participants were asked to self-rate their level of skill in relation to each outcome on a scale of 0 (no skill) to 100 (highly expert).

An example of a skills outcome is given below:

Over the last week:

I have the skills to talk about and explore my client’s ethnic identity in sessions

0 (No skills)----25 (Novice)----50 (Competent)----75 (Proficient)----100 (Highly Expert)

Ethnic identity development

Ethnic identity is defined as ‘the identity that develops as a function of one’s ethnic group membership … Ethnic identity is conceptualised as a component of one’s overall identity and will vary in its salience across individuals’ (Umaña-Taylor, Reference Umaña-Taylor, Schwartz, Luyckx and Vignoles2011). The Ethnic Identity Development Scale (EIS; Umaña-Taylor et al., Reference Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian and Bámaca-Gómez2004) was adapted for use in this study, which considers three components of ethnic identity development: the degree to which someone has explored their ethnicity (exploration), the degree to which they have resolved what their ethnic identity means to them (resolution), and the affect associated with that resolution (valence). The EIS is a validated and reliable measure of ethnic identity development (α=.84–.89; Umaña-Taylor et al., Reference Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian and Bámaca-Gómez2004).

One outcome question relating to each component of ethnic identity from the EIS was selected and adapted. Participants were asked to provide weekly self-ratings related to each of the three measures on a scale of 0 to 100.

An example of an ethnic identity outcome is given below:

In relation to the last week, how well do the following statements describe you:

I have had a clear sense of what my ethnicity means to me (Resolution)

0 (Not well at all)----25 (Slightly well)----50 (Moderately well)----75 (Very well)----100 (Extremely well)

Wellbeing

Personal wellbeing and therapist wellbeing, as distinguished by the DPR model (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006), were also included as outcomes. A simple visual analogue style rating scale was developed by the researcher to measure both wellbeing outcomes. The scale ranged from 0 to 100, and participants provided their respective personal and therapist wellbeing ratings each week.

An example of a wellbeing outcome is given below:

Over the last week, how would you rate:

Your personal wellbeing

0 (Poor wellbeing)----25 (Fair wellbeing)----50 (Good wellbeing)----75 (Very good wellbeing)----100 (Excellent wellbeing)

Procedure

Participants were asked to complete the outcome questionnaire each week, providing self-ratings on the skills, ethnic identity development and wellbeing measures. Participants also provided information on the number of service users from a minoritised ethnicity they worked with, and the amount of time they spent on the SP/SR programme each week. This was done across the baseline, SP/SR and follow-up phases. Data were collected pseudonymously.

During the SP/SR phase, participants worked through each of the nine programme modules independently, with two weeks allocated to each module. At the end of each module, participants were invited to join a fortnightly online reflective group (for an hour and a half), which was facilitated by the two programme authors, Dr Alasdair Churchard (a clinical psychologist who self-identifies as a mixed-race cis male with Afro-Caribbean heritage) and Dr Richard Thwaites (a clinical psychologist who self-identifies as a White British cis male), and Leila Lawton (a CBT therapist who self-identifies as a Ugandan-British cis female, racialised as Black). The purpose of the reflective group was to offer an opportunity to reflect collectively on the process of completing the programme, as well as a facilitated peer support space to consider the impact of ethnicity within their practice. The facilitators also received their own supervision around the running of this space.

Data analysis

Visual analysis is the primary analysis for SCED data. The What Works Clearinghouse (WWC; Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010) process for conducting a visual analysis was used.

For each variable, data were first visually inspected, following which statistical analyses of baseline stability and non-overlap data were completed. Tau-U was the chosen statistical analysis, which is a non-parametric technique for measuring data non-overlap between phases of data, and is one of the more robust existing methods of analysing SCED data and allows the correction of baseline trend if indicated (Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber2011). Missing data were retained in the analysis.

The analysis was conducted in two stages: the first stage of the analysis explored whether the SP/SR programme had an effect on each of the outcome variables, therefore baseline and intervention phases were compared for the six completers. Following this, the second stage of the analysis examined if these effects were sustained at follow-up for the three participants who completed sufficient data, therefore a comparison between the intervention and follow-up phase was done.

Data were graphed in Excel. In addition, two online programmes were used to support the visual and statistical: the single case research Tau-U calculator (Vannest et al., Reference Vannest, Parker, Gonen and Adiguzel2016) and the SCDA shiny web app (De et al., Reference De, Michiels, Vlaeyen and Onghena2020).

Results

The results are presented for the six participants who completed the SP/SR programme; however, follow-up data were only considered for participants A, C and E as they provided sufficient data.

A summary of contextual information provided weekly by participants is presented first. The visual and statistical analyses for each outcome variable are then presented, to explore the overall and individual effects of the SP/SR programme on skill development, ethnic identity development and wellbeing. As explained in the Method section, Tau-U was the chosen statistical analysis, which is a non-parametric technique for measuring data non-overlap between two phases of data. In this study, data non-overlap was first contrasted between the baseline and SP/SR phases, followed by the SP/SR and follow-up phases, and this was done for each outcome variable. To demonstrate an effect of the SP/SR programme on an outcome, statistically significant non-overlap was needed (p-value of <0.05) between the baseline and SP/SR phases for at least one participant in each of the three baseline conditions, that is, three demonstrations of an effect.

For ease of presentation of the visual data, only linear trends across outcomes have been presented in this section. The visual plots of the raw data for each outcome are presented in the Supplementary material (section C); the means and standard deviations are also presented in the Supplementary material (section D).

In this paper, of the 15 outcome variables, the results of 12 are presented below as they were directly addressed by the SP/SR programme. The three remaining skills outcomes are presented in the Supplementary material (section E). The findings from these outcomes suggest an overall increase in level and a positive trend from baseline to the SP/SR phase. However, only some participants showed significant improvements, and this was not replicated across all baseline conditions for any outcome. In addition, there were not sufficient data collected for the skills outcome relating to being a supervisor, as data relating to this were only collected across two baseline conditions.

Contextual information

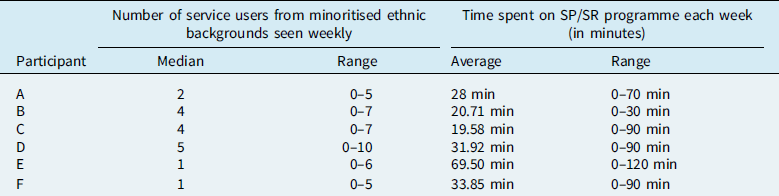

Participants provided weekly information on the number of service users they saw who were from minoritised ethnic backgrounds, and the amount of time they spent on the SP/SR programme each week. This information is summarised in Table 3.

Table 3. Weekly number of service users from minoritised ethnic backgrounds and time spent on SP/SR programme

Overall, it appeared that participants varied in the number of minoritised ethnic service users they saw each week, with participants B, C and D seeing a greater number of service users from these groups. There was also notable variation in the amount of time spent weekly on the SP/SR programme, both within and across participants. Participants E, F, D and A, on average, spent the most time on the SP/SR programme.

Participants were also able to provide additional information, if relevant, to contextualise their ratings for each week. Examples included illness, significant life events and global/political events.

Skills in working with ethnicity

For skills in working with ethnicity, seven self-rated outcomes were considered. For ease of presentation, these are shown within two broad categories: technical skills and reflective skills.

Technical skills

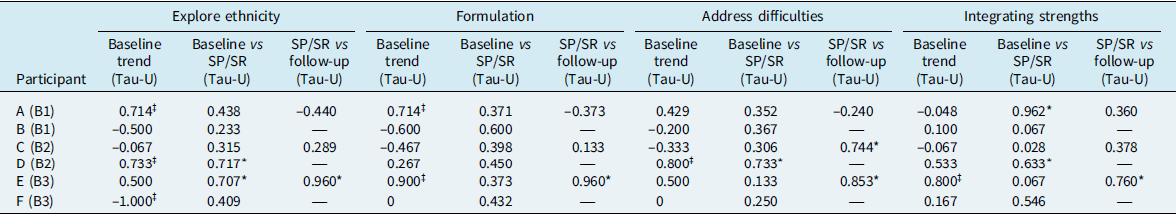

Participants showed varying baseline trends across the four technical skill outcomes. The statistical analysis showed the baseline trends were significant in some cases, therefore baseline corrections were applied (as seen in Table 4).

Table 4. Tau-U analysis of baseline trend, baseline SP/SR comparison and SP/SR follow-up comparison for technical skill outcomes

B1, baseline 1; B2, baseline 2; B3, baseline 3.

* Significant change (p≤0.05);

‡ baseline correction applied.

The visual analysis of all four outcomes generally showed high degrees of variability, particularly within the SP/SR phase. All participants showed an increase in level from the baseline to the SP/SR phase on outcomes relating to skills in exploring ethnicity and including this within formulations. For the outcomes relating to addressing difficulties related to ethnicity and integrating strengths, five out of six participants showed an increase in level, with participants E and B showing small decreases in level, respectively. Participants generally appeared to show an increasing trend in the SP/SR phase across all four technical skills (as in Fig. 2). The subsequent statistical analysis showed some differing findings across the different outcomes (as in Table 4). Two participants appeared to make significant improvements during the SP/SR phase in the skills related to exploring ethnicity and integrating strengths outcomes, and one participant in the addressing difficulties related to ethnicity outcome. Most notably, participant D appeared to show significant improvements across all three outcomes. Interestingly, none of the participants showed significant improvements in skills related to including ethnicity within formulations. Where improvements were significant, these were only replicated across a maximum of two baseline conditions.

Figure 2. Linear trend lines for technical skill outcome.

Between the SP/SR and the follow-up phase, participants C and E generally appeared to show an increase in level and an increasing follow-up trend across all four technical skills outcomes. Participant E appeared to make significant gains within the follow-up phase across all four outcomes, with participant C doing so on the skills in addressing difficulties related to ethnicity outcome. In contrast, participant A appeared to show a decrease in level and a decreasing follow-up trend, but these were not significant for any of the outcomes. Therefore, any improvements made during the intervention phase were generally maintained in the follow-up phase across all three baseline conditions.

Reflective skills

Participants showed varying baseline trends across the three reflective skills outcomes, which were significant in some cases, and so baseline corrections were applied (as seen in Table 5).

Table 5. Tau-U analysis of baseline trend, baseline SP/SR comparison and SP/SR follow-up comparison for the reflective skill outcomes

B1, baseline 1; B2, baseline 2; B3, baseline 3.

* Significant change (p≤0.05);

‡ baseline correction applied.

The visual analysis across the three outcomes generally showed high degrees of variability. All participants showed an increase in level in the SP/SR phase on skills related to managing personal resonances, and five out of six participants showed the same on the remaining two reflective outcomes. All participants showed an increasing SP/SR phase trend across all three outcomes (as in Fig. 3). The associated statistical analysis revealed that only participant A showed a significant improvement in skills relating to managing personal resonances and identifying their own biases. In contrast, participants A, D and F showed significant increases in their ratings of skills related to addressing their own ethnic similarities and differences, which crucially was replicated across the three different baseline conditions.

Figure 3. Linear trend lines for reflective skill outcomes.

Comparing the SP/SR and follow-up phases, participants C and E generally showed an increase in level and, in most cases, showed an increasing follow-up phase trend across the reflective skills. These improvements in the follow-up phase were significant for participant E for all three skills. Like the technical skills, participant A appeared to show a decrease in level and a downward trend in the follow-up phase, but these were not significant for any of the outcomes. Again, improvements made during the SP/SR phase were generally maintained in the follow-up phase across all three baseline conditions.

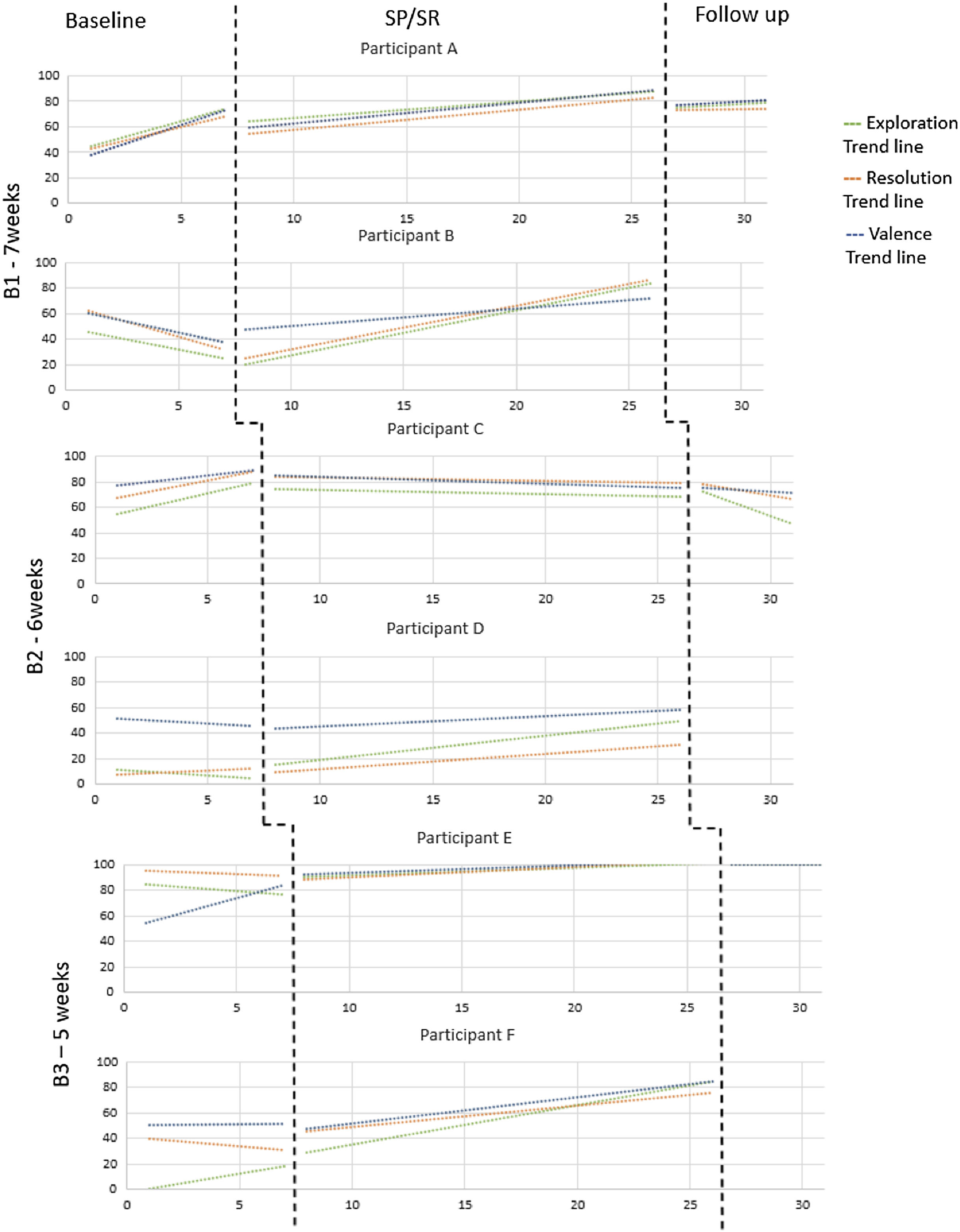

Ethnic identity development

Across all three ethnic identity development outcomes, although some participants showed increasing baseline trends, statistical analysis revealed that none of these trends was significant (as in Table 6).

Table 6. Tau-U analysis of baseline trend, baseline SP/SR comparison and SP/SR follow-up comparison for the ethnic identity development outcomes

B1, baseline 1; B2, baseline 2; B3, baseline 3.

* Significant change (p≤0.05).

There was generally some degree of variability across baseline and SP/SR phases across all three ethnic identity outcomes. All participants showed an increase in level from the baseline to intervention phase across all three outcomes, except for participant C, who showed a slight decrease in level for valence related to their ethnic identity. These changes appeared gradual across the three outcomes. Related to this, all participants apart from participant C also showed an increasing SP/SR trend across all three outcomes, which was the desired trend direction (as in Fig. 4). Participant C showed a decreasing intervention trend on valence related to ethnic identity, indicating a more negative view of their ethnic identity as the SP/SR programme progressed, but this reduction was not statistically significant. Statistical analysis indicated that scores significantly improved during the SP/SR phase for participants A, E and F for exploration of ethnic identity, participants A and F for resolution related to ethnic identity, and participants E and F for valence related to ethnic identity. However, in all cases, these improvements were only replicated across two baseline conditions.

Figure 4. Linear trend lines for ethnic identity development outcomes.

From the SP/SR to the follow-up phase, visual analysis indicated an increase in level for participants A and E, who also showed an increasing trend in the follow-up phase across all three outcomes. Statistical analysis (as in Table 6) suggested that for participant E, there was a further significant increase in exploration and resolution ratings in the follow-up phase. For participant C, although there was a reduction in scores across all three outcomes, this was only statistically significant for resolution related to ethnic identity.

Wellbeing

For both personal and therapist wellbeing, despite some participants showing an increasing baseline trend, none of these was found to be statistically significant (as in Table 7).

Table 7. Tau-U analysis of baseline trend, baseline SP/SR comparison and SP/SR follow-up comparison for the wellbeing outcomes

B1, baseline 1; B2, baseline 2; B3, baseline 3.

* Significant change (p≤0.05).

There were generally high levels of variability for both wellbeing outcomes, and in the case of personal wellbeing, variability reduced from baseline to the SP/SR phase for most participants. From the baseline to the SP/SR phase, the level increased for most participants across both personal and therapist wellbeing, with the exception of participant B, whose level reduced on both, and participant F, whose level reduced on personal wellbeing. Five out of the six participants also showed increasing SP/SR phase trends on both outcomes (as in Fig. 5). The Tau-U comparison of the baseline and SP/SR phases showed differing results for personal and therapist wellbeing outcomes. For personal wellbeing, only participant E appeared to show a significant improvement in wellbeing scores during the SP/SR programme. In contrast, for therapist wellbeing, participants A, E and F showed a significant increase in wellbeing scores during this phase. However, these improvements in therapist wellbeing were only replicated across two baseline conditions.

Figure 5. Linear trend lines for wellbeing outcomes.

For the SP/SR to follow-up phase comparison, the visual analysis appeared to show a mixed pattern. Participants A and E showed a further increase in level and trend in the follow-up phase, with these gains being statistically significant in the case of participant E for both personal and therapist wellbeing. Conversely, participant C showed a reduction in level and trend for both personal and therapist wellbeing in the follow-up phase, with a significant reduction in therapist wellbeing ratings.

Discussion

This empirical paper describes the evaluation of a novel SP/SR programme for CBT therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds, using a multiple baselines single case experimental design. SP/SR has not previously been adapted to develop the cultural competence of therapists and this is also the first SP/SR programme that has explicitly focused on the ethnic identity of therapists. Therefore, the findings from this evaluation seek to add to the research base around cultural competence, as well as to the personal and professional development of therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds. This research also aimed to expand the quantitative literature and research methods around SP/SR, with the rigorous application of the WWC standards (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010).

The primary aim of this evaluation was to explore the programme’s impacts on therapists’ self-rated skill in working with ethnicity in their clinical practice, their ethnic identity development, and personal and therapist wellbeing. The discussion for each is presented below.

Therapist skill in working with ethnicity

The results indicate that, overall, over the course of the SP/SR programme, most participants appeared to show improvements across the seven skills outcomes, with observed increases in level and trend during the SP/SR phase. These improvements in skills ratings were significant in the case of some participants, with the greatest number of participants showing significant improvements in the skills to identify and address similarities and differences in ethnicity (three participants), followed by the skills to explore ethnicity (two participants) and skills to integrate strengths related to ethnicity (two participants). However, significant improvements were only replicated across the three baseline conditions for the skills to identify and address similarities and differences in ethnicity, therefore, we can only conclude that improvements were as a result of the SP/SR programme for this outcome. It is possible that the SP/SR programme had the greatest impact on the skills to explore and address similarities and differences in ethnicity as it considers the ethnic identity of therapists as it relates to that of service users, which is something that is often lacking within traditional cultural competence training (Faheem, Reference Faheem2023a) and might be specifically targeted by an SP/SR training methodology and the current intervention. It may also be possible that the engagement of the reflective bridge between the personal and therapist selves, through the self-practice exercises and related reflective questions contained in the programme, may have had a particular impact on this outcome (Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018).

In contrast, none of the participants appeared to show significant improvements in skills related to including ethnicity within formulations. This finding is particularly surprising, given that two of the modules of the SP/SR programme focused on developing CBT formulations incorporating ethnicity/ethnic identity. It is difficult to ascertain why this might be from the quantitative data collected in this study.

Ethnic identity development

Participants appeared to show increasing levels and trends in relation to the three ethnic identity development outcomes during the SP/SR phase, but these were only significant in the cases of some participants, with the greatest number of participants showing significant improvements on the outcome related to the exploration of their ethnic identity (three participants). Although three participants showed significant gains on this outcome during the programme, this was not replicated across the three baseline conditions, and therefore it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions that improvements were as a result of the SP/SR programme.

It is interesting that, of the three ethnic identity development outcomes, there was a greater impact of the programme on the exploration component than on the resolution and valence components. Some models of ethnic identity development highlight the importance of exploration (Phinney, Reference Phinney, Bernal and Knight1993; Phinney and Ong, Reference Phinney and Ong2007), and it seems the current SP/SR programme may have offered therapists an important opportunity for exploration. This is consistent with assertions within the CBT and related cultural competence literature that highlight a need for therapists to have spaces to explore their own ethnicity and its implications on their practice (Faheem, Reference Faheem2023a; Haque et al., Reference Haque, Thapa and Kunorubwe2021; Naz, Reference Naz2021).

Wellbeing

Most participants appeared to show increasing levels and trends in the ratings of their personal and therapist wellbeing. However, it appeared that more participants experienced a significant benefit for wellbeing related to their therapist selves (three participants), than personal selves (one participant). Considering these findings within the DPR and PP models (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones, Reference Bennett-Levy and Finlay-Jones2018), it is possible that more people engaged in the SP/SR programme on the level of their therapist self, and so greater benefit was experienced related to this outcome. In addition, lower personal wellbeing ratings could be accounted for by personal events that participants highlighted when contextualising their weekly ratings, including reports of bereavement and illness that would understandably have impacted on perceived levels of personal wellbeing.

Therefore, looking at the overall impacts of the SP/SR programme on the three outcome areas, there appeared to be some evidence that the programme led to improvements in therapist skill, specifically in relation to identifying and addressing similarities and differences in ethnicity outcome with service users. There also appeared to be a general increase in level and trend across outcomes during the programme, but these were not significantly improved in all cases. These findings may suggest that although participation in the programme was beginning to have a positive impact on the different outcome areas, skills in working with ethnicity, ethnic identity development and wellbeing are all dynamic factors, and change is often a longer or even life-long process. This is highlighted in particular within the cultural competence and ethnic identity development literature, where specific training programmes or interventions may just offer a starting point in a continuous journey of development (Benuto et al., Reference Benuto, Singer, Newlands and Casas2019; Curtis et al., Reference Curtis, Jones, Tipene-Leach, Walker, Loring, Paine and Reid2019; Haque et al., Reference Haque, Thapa and Kunorubwe2021; Maehler, Reference Maehler2022). Importantly, it appeared that none of the participants experienced any significant negative impacts because of this SP/SR programme during the course of the intervention.

A secondary aim of this study was to consider if any impacts of the programme were maintained after the completion of the programme. The findings from the comparison of the SP/SR and follow-up phases presented a more mixed picture, where improvements were maintained for two of three participants, with participant E making further gains across most outcomes. It may be that the follow-up phase offered a period of consolidation for participant E, allowing for further gains to be made. In contrast, participant C appeared to show some deterioration at follow-up, with a significant reduction in resolution related to their ethnic identity and in levels of therapist wellbeing. It is possible that a greater consideration of ethnic identity during the SP/SR programme, which included a consideration of negative experiences and experiences of discrimination related to ethnic identity, may have led to a reduced sense of resolution. It is also possible that these reductions reflect unknown factors outside of the SP/SR programme.

Individual impacts of the SP/SR programme

A key finding from this evaluation is that different participants appeared to experience differential impacts and levels of benefit from the SP/SR programme. Participant D seemed to experience the greatest level of benefit related to the technical skills outcomes. In contrast, it appeared that participants A, E and F experienced the greatest benefit from the programme overall, showing significant improvements related to reflective skills, ethnic identity development and therapist wellbeing outcomes. Looking at the participant demographic and contextual information, it appeared that participant D had the least clinical experience of the group, being the most recently qualified, while participants A, E and F had varying lengths of experience, ranging from 2.5 to 10 years. Therefore, it is possible that the impact of the programme on the development of more concrete, technical skills was experienced by the novice therapist, with the more experienced therapists experiencing some benefits related to reflective skills, their own ethnic identity development and therapist wellbeing. Similar findings have been reported in other SP/SR studies, where declarative information and procedural skills are enhanced for novice therapists, and skill refinement as well as personal and professional benefits are experienced by experienced therapists (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Bennett-Levy and Haarhoff; Reference Bennett-Levy, Haarhoff and Dimidjian2019; Thwaites et al., Reference Thwaites, Bennett-Levy, Davis, Chaddock, Whittington and Grey2014).

In addition, it appeared that participants A, D, E and F also spent the greatest amount of time on the SP/SR programme. Therefore, it is likely that their level of engagement in the SP/SR programme led to them experiencing the greatest levels of benefit. These findings are supported by existing SP/SR research which sets out differential impacts of SP/SR programmes for individuals, with engagement being a central factor related to outcome (Bennett-Levy and Lee, Reference Bennett-Levy and Lee2014; Chaddock et al., Reference Chaddock, Thwaites, Bennett-Levy and Freeston2014).

It is hard to fully interpret these findings within the wider literature, as this is the first study to use an SP/SR methodology to develop therapist skill in working with ethnic diversity and existing studies vary greatly in their methods of training (Bentley et al., Reference Bentley, Jovanovic and Sharma2008; Truong et al., Reference Truong, Paradies and Priest2014). However, the initial support for the use of SP/SR in developing the skills of therapists in working with ethnicity in clinical practice is promising.

Limitations

The main limitation of this research project is that is it difficult to fully contextualise these findings and to generalise these findings more widely. It is difficult to know if the hypothesised mechanisms of change within the programme are reflected in the findings from this study. Therefore, it will be important to interpret these findings alongside the qualitative evaluation of this programme (Malik, Reference Malik2024).

A second limitation of this study is around the outcomes and related measurements. This evaluation relied on the use of unstandardised, adapted, and self-rated outcomes. While this is not uncommon within SCED, SP/SR and cultural competence research (Jongen et al., Reference Jongen, McCalman and Bainbridge2018; Krasny-Pacini and Evans, Reference Krasny-Pacini and Evans2018; McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015), they present some issues around validity and self-reporting bias.

Finally, the current SP/SR intervention is pitched at the level of the individual therapist. However, it is increasingly acknowledged that change at the individual level is insufficient in bringing about transformative and lasting change for both therapists and service users from minoritised ethnic backgrounds, and there is more that needs to be done at a structural and institutional level (Beck and Naz, Reference Beck and Naz2019; Lawton et al., Reference Lawton, McRae and Gordon2021; Naz et al., Reference Naz, Gregory and Bahu2019).

Future directions

As this is the first SP/SR programme and evaluation of its kind, it would be important for further evaluations to take place, addressing the limitations of the current study. It would be important for future studies to address the limitations around the measurement of outcomes, where the validation of simple measures prior to use in this study would be helpful. Adopting a mixed methods analysis may also be helpful in future evaluations, where the mechanisms of change may be examined in greater detail.

In addition, while the DPR model has been applied to the development of the cultural competence of White therapists (Churchard, Reference Churchard2022), this has, so far, not been extended to the development of similar skills for therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds. It would be important for a comprehensive theoretical model to be developed. It is hoped that the qualitative (Malik, Reference Malik2024) and current quantitative evaluation of this SP/SR programme may inform this model, which may guide further research (McGillivray et al., Reference McGillivray, Gurtman, Boganin and Sheen2015).

Key practice points

-

(1) Given the initial support for the use of SP/SR as a methodology for developing therapist reflective skill in working clinically with ethnicity, consideration may be given to integrating a similar approach within existing CBT professional training programmes. It might be that this programme offers a novel and practical way of developing therapist skills.

-

(2) The importance of having a space to consider ethnicity for therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds has been highlighted. The same or similar initiatives may offer this opportunity within professional training and/or service-specific contexts.

-

(3) SP/SR programmes appear to have differential impacts on individuals, depending on their level of experience as well as on their levels of engagement with SP/SR. This may support the development of further iterations of the current programme or other similar initiatives.

-

(4) The WWC standards (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010) for SCEDs may be replicated in future quantitative evaluations of SP/SR, where there is limited, quantitative empirical research (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2019).

-

(5) Co-production is integral to the development of any initiatives, that aim to support the personal and professional development of therapists from minoritised ethnic backgrounds.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X24000448

Data availability statement

The data from this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data will not be made publicly available due to data protection/ethical considerations.

Acknowledgements

The authors would first like to recognise the commitment of the CBT therapists who gave their time to participate in this programme. The authors would like to thank all the experts who consulted on this project: Dr Isaac Akande, Dr Reena Vohora, Dr Chris Gaskell and Dr Steve Kellett. Their input into the design and evaluation has been invaluable. The lead author would also like to thank Carla Quan-Soon, for providing a much-needed reflective space to consider the personal impacts of this research project. Finally, the facilitators would also like to thank Dr Roberta Babb for her insightful and supportive supervision.

Author contributions

Sakshi Shetty Chowdhury: Conceptualization (lead), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Investigation (equal), Methodology (lead), Visualization (lead), Writing - original draft (lead); Alasdair Churchard: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (equal), Methodology (supporting), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Leila Lawton: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Zara Malik: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Richard Thwaites: Conceptualization (supporting), Investigation (equal), Methodology (supporting), Resources (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal); Henry Clements: Conceptualization (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (equal), Writing - review & editing (equal).

Financial support

The first author received a small budget for research costs from the UCL Doctorate in Clinical Psychology programme.

Competing interests

Richard Thwaites is the Editor-in-Chief of the Cognitive Behaviour Therapist. He was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he is listed as an author. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest related to this publication.

Ethical standards

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval for the SP/SR programme and the related analyses was granted by the UCL Research Ethics Committee (committee approval ID number: 22167/001). Informed consent was received from the participants for their involvement in the research and the publication of results.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.