Introduction

The world Englishes (WEs) paradigm describes the spread of English in three concentric circles (Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985) – the Inner Circle (e.g., the USA, UK, and Australia), the Outer Circle (e.g. India, Philippines, and Singapore), and the Expanding Circle (e.g. China, Indonesia, and Thailand). With Englishization and nativization outside the Inner Circle and the changing demographics of English users (e.g. non-native speakers [NNSs] considerably outnumber the native speakers [NSs] in the Inner Circle [Crystal, Reference Crystal1995; Graddol, Reference Graddol1999], the WEs research strongly advocates to recognize the NNS varieties. Until today, the WEs paradigm has not only posed challenges to, but also encouraged changes in, the language testing (LT) profession that has been traditionally relying on the Inner Circle standard (e.g., Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985; Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Davies, Hamp–Lyons & Kemp, Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012; Brown, Reference Brown2014).

The discussion of the impacts of WEs on LT has been centered on standard/norm and consequent reliability and validity issues related to large-scale international standardized language proficiency tests (ISLPTs) that are developed and used in the Inner Circle; the conversation has also covered local standard language proficiency tests (LSLPTs) in the Outer Circle. However, locally developed and administered tests in the Expanding Circle context has been understudied, despite their growing impacts on the large population of users of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) (Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002).

This study investigated to what extent LSLPTs in the Expanding Circle have been, and could further be, influenced by the WEs paradigm. By examining the College English Test (CET), one of the largest standardized English proficiency tests developed and administered locally in China, the study is believed to shed light onto the possible ways for negotiation and cooperation, instead of confrontation, between WEs and LT. The research will also extend the literature on WEs and LT in the Expanding Circle and ‘broaden current understanding of the full range of users and uses of the [English] language’ (Berns, Reference Berns2005: 85).

Literature review

World Englishes (WEs) and language testing (LT): The confrontation

The tension between WEs and LT resides mainly on the standard/norm to use and the consequent reliability (or bias) and validity issues. In a nutshell, WEs criticizes LT for relying solely on the Inner Circle standard (e.g. Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985; Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012; Brown, Reference Brown2014), or the two varieties – American and British English (Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Hamp–Lyons & Davies, Reference Hamp–Lyons and Davies2008; Davies, Reference Davies2009) used by educated NSs (e.g. Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg1993, Reference Lowenberg2002; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2006), hence ‘disconnect[ed] from the insights in analysis of English in the world context’ (Davidson, Reference Davidson, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006: 709). In addition, using the Inner Circle standard in an L2 test raises serious fairness concerns (e.g. Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Brown, Reference Brown2004) such as discriminating against NNSs who typically have limited exposure (Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985, Reference Kachru1992; Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003) or relevance (Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2006; Taylor, Reference Taylor2006) to this standard, misinterpreting ‘deviations’ as ‘errors’ (e.g. Kenkel & Tucker, Reference Kenkel and Tucker1989; Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg1993; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2006), etc. Further, the construct validity is questioned when an L2 assessment leaves out NNS varieties (e.g. Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg1993; Brown, Reference Brown2004; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006). Another issue related to construct validity is LT's tradition to have limited the definition of language proficiency to a monolithic construct that focuses on linguistic forms and correctness based on the NS standards (e.g. Matsuda, Reference Matsuda2003; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018; Brown, Reference Brown, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020), despite the strong argument that English language proficiency is a multidimensional construct which also includes textual and pragmatic competence (e.g. Bachman, Reference Bachman1990; Bachman & Palmer, Reference Bachman and Palmer1996; Brown, Reference Brown, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020).

To such criticisms from the WEs research, LT researchers have rebutted with concerns regarding the importance of standard in testing (e.g. Lukmani, Reference Lukmani2002; Davies, Reference Davies2009), the insufficiency and inconsistency in codification of NNS varieties (e.g. Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006; Davies, Reference Davies2009), unacceptance from stakeholders (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Brown, Reference Brown2004, Reference Brown2014, Reference Brown, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020; Taylor, Reference Taylor2006), as well as similar bias issues arouse with replacing the ‘hegemony of the old with the hegemony of the new’ (Berns, Reference Berns2008: 333) and ‘all the attendant consequences for those lacking the command of the new code’ (Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006: 296).

World Englishes (WEs) and language testing (LT): The negotiation and cooperation

Despite the tensions between WEs and LT, language testers are believed to have been ‘responding to, not ignoring, WEs issues’ (Brown, Reference Brown2014: 12; Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018). Some tests, mostly ISLPTs that target candidates who intend to live and study in the Inner Circle, have taken a weak approach (Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012) and mainly accommodated to the NNS candidates without de-centering the Inner Circle standard (ibid; Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006). For instance, the International English Language Testing System (IELTS) incorporated social and regional Inner Circle language variations into the reading and listening texts, used material writers from not only the U.K., but also Australia and New Zealand, and hired proficient NNSs as raters of the oral and written tests (Taylor, Reference Taylor2002). In addition, the Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOEFL) has explored L2 accents in listening assessment (Elder and Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006). Empirical studies on using proficient NNS raters in the test have also been conducted (e.g. Chalhoub–Deville & Wigglesworth, Reference Chalhoub–Deville and Wigglesworth2005; Lazaraton, Reference Lazaraton2005; Hamp–Lyons & Davies, Reference Hamp–Lyons and Davies2008), which tend to suggest including NNS raters and training them to attend more to mutual intelligibility (e.g. Smith, Reference Smith1992; Berns, Reference Berns2008) and communicative effectiveness than NS grammatical competence (Matsuda, Reference Matsuda2003; Taylor, Reference Taylor2006; Elder & Harding, Reference Elder and Harding2008; Brown, Reference Brown2014; Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018) and only penalize errors that hinder communication (Taylor, Reference Taylor2006).

Others, especially English as a lingua franca (ELF) researchers, have practiced a stronger approach (Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012) that intends to take ‘a new orientation towards the test construct’ (ibid: 132). Manifestations of the strong moves can involve implementing new standard(s) (ibid; Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006), such as EFL or local varieties that are considered as valid in their own right (Seidlhofer, Reference Seidlhofer2001; Jenkins, Cogo, & Dewey, Reference Jenkins, Cogo and Dewey2011), or even a more thorough shift of the assessment focus from formal accuracy to communicative effectiveness. For instance, it is suggested to avoid discrete measures of linguistic forms (Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018) and use performance-based assessment that simulates real-life communications in relevant contexts (Brutt–Griffler, Reference Brutt–Griffler2005; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006), such as paired tasks (e.g. Fulcher, Reference Fulcher1996; O'Sullivan, Reference O'Sullivan2002; Bonk, Reference Bonk2003). To this end, sampling should come directly from the local contexts, focusing on local topics and a diversity of NNS accents (Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006); NNS interlocutors with different proficiency levels can be used to elicit strategic competence such as self-repair, speech accommodation, and meaning and difference negotiating, etc. (ibid). Although ‘worth speculating’ (ibid: 290), the strong approach faces challenges in practicality due to the dubious status (especially codification and acceptance by stakeholders) of the new norms.

A less charted area: Local language testing in the Expanding Circle

The conversation between WEs and LT has mainly revolved around large-scale ISLPTs developed and used mainly in the Inner Circle context (Criper & Davies, Reference Criper and Davies1988; Clapham, Reference Clapham1996). Even though research in international language (EIL) (e.g. McKay, Reference McKay2002; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Schneider, Reference Schneider2011) and English as a lingua franca (ELF) (e.g. Seidlhofer, Reference Seidlhofer2001; Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2002, Reference Jenkins2006; Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006) have enriched the WEs research on testing outside the Inner Circle context, much more weight has been placed onto the Outer Circle than the Expanding Circle. Even in studies which cover both circles, much of the discussion arguing for the use of local norms in fact does not apply to the Expanding Circle given the premature stage of codification of local norms. As commented by Lowenberg (Reference Lowenberg2002), there has been a lack of research on the LT in the Expanding Circle context, which holds ‘the world's majority of English users’ (p. 431).

Recent new understandings of the complex and dynamic community (Berns, Reference Berns2005) demand more studies on the local language testing in the Expanding Circle. Originally regarded as norm-dependent (Kachru, Reference Kachru, Quirk and Widdowson1985), the Expanding Circle has recently seen increasing use of English as a second language (ESL) in addition to English as a foreign language (EFL), for a mixture of inter-national and intra-national purposes (Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Berns, Reference Berns2005; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006); there has also been growing discussion of local varieties in this context (e.g. Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Davies, Reference Davies2009). Take China as an example. English in China today is used mainly as a global language in international, multicultural settings (Pan & Block, Reference Pan and Block2011) for economic, social, cultural, and scientific communications (McArthur, Lam–McArthur & Fontaine, Reference McArthur, Lam–McArthur and Fontaine2018). Besides, English is also used for intra-national purposes in specific domains such as medical, engineering, and media (Zhao & Campbell, Reference Zhao and Campbell1995). ‘China English’ (Ge, Reference Ge1980), which refers to the educated variety (typically the English versions of Chinese idioms or slang), has begun to be considered a potential candidate for the standard English variety in China (Hu, Reference Hu2004; Honna, Reference Honna2020).

Very little research has closely studied the LSLPTs in Expanding Circle countries. Lowenberg's (Reference Lowenberg2002) article titled ‘Assessing World Englishes in the Expanding Circle’ in fact examined the use of an ISLPT, the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC), rather than LSLPTs in Expanding Circle countries such as South Korea, and China. Further, studies (e.g. Davidson, Reference Davidson, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006; Elder & Davies, Reference Elder and Davies2006; Davies, Reference Davies2009; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012) that discuss local testing in the Expanding Circle are rather theoretical instead of data-driven. The only research that has been found to have investigated the local testing practice in the Expanding Circle is Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003), which reported findings from a seminar about the local English proficiency tests (i.e. NMET and CET) in China, among other tests in some Outer-circle countries. Davies et al.'s (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003) discussion was centered on the selection of contents/texts, scoring, and rater training of the CET in comparison to the TOEFL and concluded that the test practice in China is Inner Circle norm dependent and localized in selection of contents/texts, scoring, and rater training; however, the conclusion was ‘tentative’ with no substantive examples or suggestions for changes.

Present study

This study conducted an in-depth analysis of a locally developed and administered language proficiency test in China – College English Test (CET). By examining the test specification and real test items delivered in the past three years (2017–2019), the data-driven study discusses how the ISLPT in the Expanding Circle has been assessing WEs and to what extent it can better incorporate the WEs paradigm. Research questions include:

1. What variety/varieties of English does the CET use?

2. How does the CET define language proficiency? Specifically, to what extent does the test assess NS linguistic forms and accuracy?

3. How can the CET better assess varieties of WEs?

Method

The College English Test

The College English Test (CET) is the ‘largest English as a foreign language test in the world and one of the language tests that has attracted most public attention in China’ (Zheng & Cheng, Reference Zheng and Cheng2008: 410). According to the latest version of the Test Specifications of the College English Test (National College English Testing Committee, 2016) (hereafter referred to as Specifications [2016]), the CET aims to assess general English proficiency and inform pedagogical improvement, graduate school admission, and employment in China. The CET consists of two tests – Band 4 and Band 6 – and is delivered semi-annually to college non-English majors who have completed two years and four years of the National College English Teaching Syllabuses (NCETS), respectively. Each band contains a written test (CET-4 and CET-6) and an oral test (CET-SET4 and CET-SET6). The written test comprises two selected-response sections, Listening and Reading, and two constructed-response sections, Writing and Translation. The SET is optional, but only for those who have passed a written test cutoff score. The delivery of the SET is automated, moderated by a computer examiner; tasks require both individual and paired work with a partner randomly assigned by the system. See Appendix I (Table 1-4) for the test structure.

Table 1: Summary of Tests and Items in 2017–2019

Data collection

I conducted detailed analyses of two types of data: 1. the test specification, which provides a guideline for test construction and is crucial to test development (Davidson, Reference Davidson, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012), and 2. test items, which indicate to what extent the blueprint is followed in practice rather than test writers’ expertise knowledge (Davidson, Reference Davidson, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006).

Specification

The latest version of the Specifications (2016) was downloaded from the CET official website: www.cet.edu.cn.Footnote 1 It covers three parts: 1. Descriptions of test purpose and use, structure, and rating criteria for the constructed sections; 2. A vocabulary list; 3. A sample test for each level (Band 4 and 6), with sample answers for Writing and Translation. For this study, I analyzed the first and third part, which could reveal valuable information about how the test has defined the standard and construct in practice; the vocabulary list was reserved for future studies.

Test item

I examined the items in the 36 written testsFootnote 2 delivered from 2017 to 2019, accessible in two test preparation books (Wang, Reference Wang2020a; Wang, Reference Wang2020b). Table 1 summarizes the counts of the analyzed test content by section. For convenience, citations of item sources will take such a form: CET4_06_17(1), denoting the first form of the CET-4 delivered in Jun 2017.

Data analysis

To answer the research questions, I first studied the test specification multiple times and marked wordings that could reflect the WEs paradigm. Informed by the literature review, my focus was on the statements of test purpose, question types, skills to be tested in each section, and rubrics of the Writing, Translation, and Speaking tasks. Next, I analyzed the two sample tests plus the 36 real tests (2017–2019), where I paid special attention to topic and content selection, context- or culture-specific information, accent in Listening, and the sample answers to Writing and Translation in the specification. Due to the large quantity of test items, I was able to record descriptive statistics about the characteristics (e.g. topic, sources, accent, genre) of the different sections, which help present the findings in a richer picture.

Regarding Listening and Reading, I coded each material in terms of topic, material sources, and accent in Listening (see Appendix II for sample coding). Concerning topic, I studied the material's estimated author, audience, and setting(s) based on the language and culture-specific elements (e.g. local companies and cultures) and then labeled each passage with one or more of the three broad categories – Inner Circle, Global, or Local (namely Chinese); within each topic category, I also coded specific countries or regions (as subcategories) if possible. Some passages could be identified with more than one (sub)category: for example, a listening passage about growing up in New Zealand and living in Asia would be labeled as ‘IC(New Zealand)/Global(Asia)’. Regarding material sources, only reading materials could be traced, and I did this by googling and evaluating the content match between the material and the potential source. Given a lack of standards for identifying specific accents (e.g. American or British), accent was coded based on three broad categories, namely Inner Circle, Local/Chinese, and Others. Before analyzing the data, a second coder checked all the coding and resolved any deviations through discussions with me.

Results and discussion

Research Question 1: What variety/varieties of English does the CET use?

The study echoes Davies et al.'s (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003) main finding that the CET relies, although not consistently, on the Inner Circle standard. While topics and accents in the selected-response items are dependent on the Inner Circle context, global and local varieties have also been included, especially in the constructed-response tasks.

Inner Circle varieties

Inner Circle topics in Listening and Reading

As shown in Figure 1 and 2, most of the Listening and Reading materials in the CET could be related to the Inner Circle, especially US and UK. About 50% in Listening and 70% in Reading were identified as Inner Circle topics, among which US topics accounted dominantly for about 70% and 80% in Listening and Reading, respectively. UK topics ranked the second but accounted for a much smaller proportion. A few were relevant to other Inner Circle countries such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, but the percentage was rather negligible.

Figure 1. Topics in listening materials by region (N = 180)

Figure 2. Topics in reading materials by region (N = 144)

The Specifications (2016) designates ‘original English-language materials’ (p. 1) as the sources, which could partly explain the dominant percentage of Inner Circle topics. In fact, most sources of the reading texts could be traced to Inner Circle newspapers, magazines, and websites (see Figure 3), with the top sources being NPR News, Interesting Engineering, BBC, The Guardian, and The New York Times. Of course, some of the sources target a more global audience (e.g. Interesting Engineering), but no local media sources were found.

Figure 3. Sources of reading materialsFootnote 5 (N = 144)

The test's adaptation to the original sources mainly focused on text length and difficulty at the linguistic level, preserving the content and tone as addressing mainly the Inner Circle audience. Therefore, much content information could assume background knowledge. For instance, a reading passage (CET4_12_19[1]) opens with ‘a polar wind brought bitter cold to the Midwest’ without mentioning the ‘Midwest’ of which region, apparently composing for a local audience (in the US, which could be decided based on later message that contained regions and businesses in the country, e.g. Chicago, USPS, etc.). Many topics are hardly relevant to the Chinese culture and can be unfamiliar to Chinese test takers. For instance, a reading passage (CET4_12_18[1]) about healthy lifestyle discussed only Western dishes, such as cereal, frozen oranges and apples, and macaroni-and-cheese, which are rarely seen in the Chinese diet. Another example (CET4_12_19[2]) discusses the expensive E-textbook industry in the US, which can sound strange to the Chinese students who typically purchase paper books that are rarely found to be expensive. This unselective adoption of original materials can lead to validity and bias concerns, which will be further discussed under Research Question 3.

Inner Circle accents in Listening

The Specifications (2016) openly states that the listening assessment ‘uses standard American and British accents’ (p. 6). This statement may not be easy to interpret, because in China, American and British English varieties are ‘often mixed without distinction’ (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003: 577). Even when they are used in distinction, the definition of such standard accents can differ. In a narrow sense, they refer to the American and British accents spoken by educated NSs in the U.S. and U.K. In a broad sense, each may also contain other varieties in the Inner Circle; for instance, ‘standard American accent’ can also refer to educated Canadian accent and ‘standard British accent’ to educated Australian and New Zealand accents. Nevertheless, based on the test specification, it is obvious that the test is intended to use Inner Circle accents in Listening. An examination of the sample and real tests revealed that the listening test relied exclusively on varieties of Inner Circle accents, and no Chinese or other accents were identified.

Global and local varieties

Listening and Reading

Although relying on Inner Circle sources, the CET listening and reading passages also included topics related to global contexts (see Figures 1 and 2), particularly in CET-4. Specifically, 50% (n = 90) of the listening materials could be identified as global, with 22 passages situated in European settings (e.g. Italy and France), 5 in AsiaFootnote 6, and others undefined; 42% of the reading materials could be identified as global, with 8 passages situated in Europe, 5 in AsiaFootnote 7, and others unidentified. Although a small portion, it is worth noting that two topics involving Chinese culture were found in Reading – one (CET4_12_18[3]) discusses the writer's experience of having a Chinese medicine treatment in a China Town; the other (CET4_06_18[3]) is about Neon lights in Hong Kong. The statistics indicate that global topics in general account for a large percentage of the topics in Listening and Reading. Even though topic selection within the global category relies predominantly on European and other settings, the inclusion of global cultures that have more contact with China (e.g. Asian topics) as well as the local Chinese topics can serve as a good starting point and example for further diversifying topic selection.

Writing

Most of the writing prompts are, as found in Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003), similar with the TOEFL writing test (p. 578), which are mostly argumentative as shown in the following example (CET6_12_19[1]):

(1) Write an essay on the importance of having a sense of social responsibility.

However, I disagree with Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003) that the similarity signals dependence on the Inner Circle standard. Rather, such prompts do not assume any background knowledge related to any particular contexts and therefore show that the test is doing as fair a job as the TOEFL.

More importantly, a few prompts in more recent tests have attempted to include local elements, which has not been discussed in Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003), although, again, such prompts concentrated in the CET-4 tests. For instance, the three prompts in the CET4_12_19 set asked the examinees to recommend a place/city/university to a foreign friend. In CET4_06_19(2), the prompt states:

(2) Write a news report to your campus newspaper on a visit to a Hope elementary school organized by your Student Union.

The term ‘Hope elementary school’ refers to an elementary school built and supported by charitable contributions, which has strong Chinese characteristics and is representative of the local language variety, China English.

Translation

Translation does not typically occur in ISLPTs or even LSLPTs and therefore has rarely been discussed in prior literature. Interestingly, with the purpose to ‘introduce the Chinese cultural, historical, and social development [to a foreign audience]’ (Specifications, 2016: 4), the translation topics in both CET-4 and 6 were exclusively local. For example, many original Chinese texts were about the social development in China, such as Chinese family values (CET-4, Dec 2019), the use of mobile payment in China (CET-4, Dec 2018), the museums in China (CET-6, Dec 2018), etc. Prompts focusing on Chinese history and culture covered topics such as Chinese Lion Dance (CET4_06_19), famous mountains, rivers, and lakes (e.g. Mount Tai, CET4_12_17; Yellow River, CET4_06_17), and famous dynasties in history (e.g. Ming, Song, and Tang, CET6_06_17), to name just a few.

Some translation prompts also contained ‘commonly used’ (Specifications, 2016) Chinese idioms, such as ‘ào rán zhàn fang’ (proudly bloom ,meaning flowers blooming vibrantly) (CET6_12_19[1]) and ‘chū wū ní ér bù rǎn’ (out dirty mud but not polluted,meaning emerging pure and clean from the murky water, typically used to describe the characteristics of the lotus flower) (CET6_12_19[3]), and not surprisingly, culture-loaded names of historic figures, places, and events. Translating these idioms and terms requires a mastery of the educated local English variety, China English (Honna, Reference Honna2020).

Research question 2: How does the CET define language proficiency? Specifically, to what extent does the test assess NS linguistic forms and accuracy?

The study examined the assessment goals, required skills, question types, scoring rubrics, and sample answers in the Specifications (2016) to gain an understanding of how the test defines language proficiency to be assessed. The examination reveals that the CET's assessment goal does not focus on NS linguistic forms and accuracy; rather, it emphasizes gauging overall communicative competence, regarding the local variety as acceptable and appropriate.

Item types

The CET does not contain discrete-point grammar items, which have been criticized by WEs scholars for focusing solely on NS linguistic forms and accuracy (e.g. Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg2002; Matsuda, Reference Matsuda2003; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006). Remarkably, Listening abandoned the task of ‘Compound Dictation’ (i.e. filling in blanks of a listening passage with words or phrases) (Li & Zhao, Reference Li and Zhao2016), or a listening cloze item, which has been questioned for being unable to assess high-order language abilities (e.g. Cohen, Reference Cohen1980; Buck, Reference Buck2001; Cai, Reference Cai2013). Avoiding such discrete-point grammar questions reflects the test's possible intention to deemphasize a specific standard or variety of English as the goal of assessment.

It is also worth noting that the SET contains paired interactions between Chinese test takers at different proficiency levels, which enables the elicitation of the examinees’ interactive and negotiation skills through NNS-NNS communication (Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Taylor, Reference Taylor2006; Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018). This reflects a strong move toward assessing WEs (Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012), especially when considering the possibility that, as Davies et al. (Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003) indicated, raters of the CET are proficient English speakers with Chinese as their native language. Admittedly, it is challenging to conclude whose norms are actually referred to by the Chinese raters, and it needs further research to confirm whether such NNS rater recruitment still remains nowadays; however, the scoring criteria specified in the Specifications (2016) can speak to this issue and will be discussed in the following section.

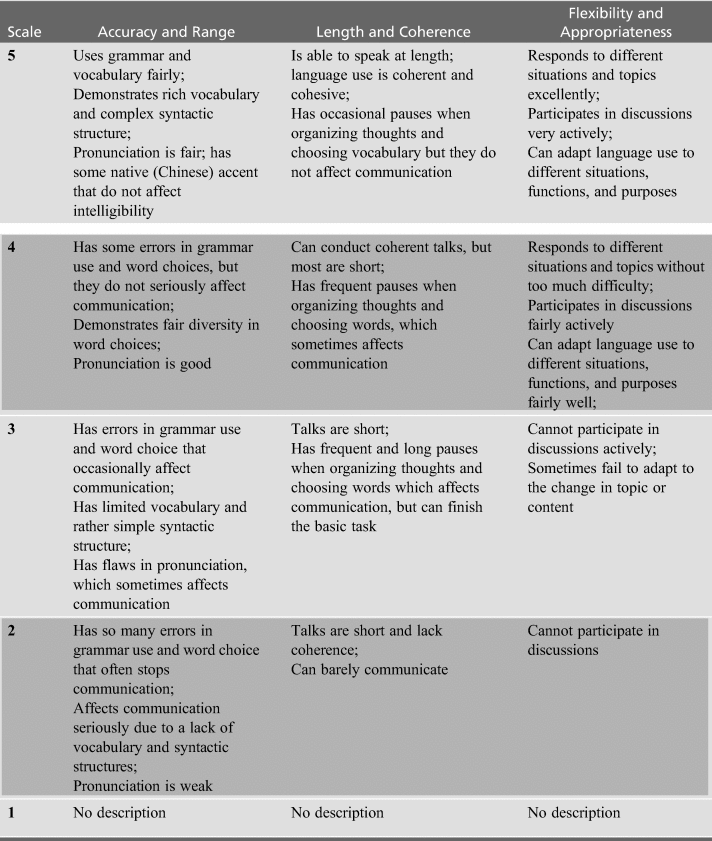

Scoring criteria

An analysis of the scoring criteria (see Appendix III) of the constructed-response items (Writing, Speaking, and Translation) in the Specifications (2016) also suggests what the CET assesses is not centered on linguistic accuracy, but communicative competence at all linguistic levels (Berns, Reference Berns, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020). For instance, the rubric of the SET covers not only ‘Accuracy and Range’ at the grammatical level, but also Length and Coherence and ‘Flexibility and Appropriateness’ at the textual and pragmatic level. Specifically, the criteria of ‘Flexibility and Appropriateness’ refers to the abilities to ‘respond to different situations and topics’, ‘participate in discussions actively’, and ‘adapt language use to different situations, functions, and purposes’ (p.11–12), emphasizing the evaluation of candidates’ competence in terms of functional effectiveness (Matsuda, Reference Matsuda2003; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012) and strategic competence (Jenkins, Reference Jenkins2006; Jenkins et al., Reference Jenkins, Cogo and Dewey2011, Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012), thus decentering the assessment of NS linguistic forms. As Elder and Davies (Reference Elder and Davies2006) pointed out, focusing the assessment on meaning making and functional effectiveness instead of language form enables a test to avoid the necessity for a description of which language norm(s) is the target, thus being considered a possible way to assess WEs or ELF.

Meanwhile, Elder and Davies (Reference Elder and Davies2006) raised the concern about what counts as an intelligible and successful conversation. Berns (Reference Berns, Nelson, Proshina and Davis2020) also claimed that communicative competence is an indispensable topic to WEs studies, and the key questions center around whose norms are considered acceptable, intelligible, and appropriate in different social contexts. An examination of the rubric descriptors and the translation and writing benchmarks in the Specifications (2016) indicates that there is no emphasis on the NS norms. For example, no reference was made to the ‘native speaker’ norms (Harding & McNamara, Reference Harding and McNamara2018); instead, ‘certain levels of native (Chinese) accent that don't affect intelligibility’ (p .4) are not penalized in the SET; additionally, the rating of all constructed items allows for ‘occasional minor errors’ (p. 5), suggesting a likely intention to differentiate ‘errors’ from ‘deviations’ and acknowledgment of the local variety. The following CET-4 benchmark translation about traditional Chinese hospitality can help us better understand how the test defines ‘minor errors’ and thus ‘intelligibility’ and ‘appropriateness’:

-

(3) The traditional Chinese way of treating guests requires hosts to prepare abundant and various dishes, and make the guests unable to finish them all. The typical menu for a Chinese feast consists of a set of cold dishes, which are served at the beginning and some hot dishes after that, such as meat, chicken, ducks, and vegetables. In most feasts, a complete fish is considered necessary unless various kinds of seafood have been served. Nowadays, Chinese people like to mix western special dishes with traditional Chinese cuisine, so it is not rare to find steak on the table. In addition, salad has gained its popularity constantly, even though Chinese people are not likely to eat dishes that have not been cooked in tradition. There is generally a soup in a feast, which can be served at the beginning or the end of the meal. Besides, desserts and fruits often mark the end of a feast. (p. 200)

Although the underlined expressions are not idiomatic or ‘correct’ under the Inner Circle standard, the response is used as the benchmark for the highest level (score 14) of writing, which means the ‘deviations’ were treated as merely differences. This suggests that the test treats the local variety as, if not the norm, at least acceptable and intelligible. The same applies to the Writing sample response, where the essay receiving the perfect score (score 14) also contains expressions that may sound strange or incorrect to NSs, such as ‘to hear such argument’ and ‘harmful for following reasons’ (p. 197). Of course, more research needs to be conducted on how raters rate in real tests to deepen our understanding of their interpretation of intelligibility, appropriateness, and acceptability in actuality.

Research Question 3: How can the CET better assess WEs?

What has been done

Following the lead of ISLPTs, the CET has taken active moves, essentially the weak approach, to assess WEs by diversifying the sampling sources within the Inner Circle. Generally, the CET fits fairly into the context of local testing in China. As a norm-dependent Expanding Circle country, China has relied on the NS-model (e.g. Kirkpatrick, Reference Kirkpatrick, Rubdy and Saraceni2006) in English education at the tertiary level (He & Zhang, Reference He and Zhang2010), which largely explains its dependence on the Inner Circle standards and echoes Hu's (Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012) advocacy to ‘make allowances for individual aspirations to Inner Circle Norms’ (p. 138). Meanwhile, the CET has taken actions to meet its purpose of assessing general English abilities in a wide range of communication contexts (Specifications, 2016). For instance, it also includes global and local elements in its input texts and item prompts and decenters the evaluation of the NS linguistic forms and accuracy by emphasizing intelligibility and communicative effectiveness. Some stronger approaches were also utilized, such as the paired interaction in the SET which has the potential to assess NNS–NNS communicative and strategic competence. The accommodations respond to the changing role of English from a way to ‘[interact] with native speakers with a focus on understanding the customs, the cultural achievements’ (Berns, Reference Berns2005: 86) to a tool for a mixture of international and intra-national purposes. The incorporation of global and local elements to the Inner Circle standards, or the Standard English plus method (Li, Reference Li2006), speaks to the test's local validity and reliability. The bias issue is also addressed when the assessment acknowledges the acceptability of the local variety and recognizes certain levels of ‘differences’ and ‘deviations’.

Recommendations

The nature of WEs tends to favor pluralism, instead of a certain, single variety or group of varieties; therefore, it is important to make ways for diversity in assessment, to prepare the English learners in the Expanding Circle for real-life communications (Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006; Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012). The following aspects of the CET should be further diversified.

The topics in Listening and Reading, as noted earlier, have been too restricted to the Inner Circle context. The local validity and authenticity of the test can be questioned when the topics and contents relate little to the culture the candidates are familiar with and do not assess students’ use of English in real life (Lowenberg, Reference Lowenberg1993; Canagarajah, Reference Canagarajah2006). Besides, topic familiarity has been suggested to play a crucial role in L2 listening and reading comprehension (Markham & Latham, Reference Markham and Latham1987; Leeser, Reference Leeser2004), since background knowledge enables the audience to connect new information to existing knowledge (Anderson & Lynch, Reference Anderson and Lynch1988) and make inferences needed for a coherent mental representation of a text's content (e.g. Kintsch, Reference Kintsch1988; van den Broek et al., Reference Van den Broek, Young, Tzeng, Linderholm, van Oostendorp and Goldman1999). Therefore, irrelevant topics can bias against the Chinese examinees who have limited exposure to the corresponding culture- or context-specific background knowledge. To better assess WEs, the test should not only diversify sampling within the Inner Circle, but it should also address the global and especially the local contexts. As mentioned earlier, among the 36 tests delivered within the three years, only two reading passages and no listening passages were situated specifically in the Chinese context. Creating space for one or two texts from the local setting in one test could be a good start to assessing WEs. Regarding global topics, test developers can also consider cultures that have more contact with China (e.g. South Korea, Japan, India, Thailand) rather than relying predominantly on European contexts.

Topic familiarity has also been proved to relate strongly with writing performance (e.g. Hamp–Lyons & Mathias, Reference Hamp–Lyons and Mathias1994; Magno, Reference Magno2008; Mahdavirad, Reference Mahdavirad2016). However, the majority of writing prompts do not relate to any local topics. Besides, the very few topics involving local varieties are not updated (e.g. the ‘Hope elementary school’ topic). Therefore, the test needs to incorporate more local and updated topics to the writing prompts.

The accents used in Listening, although not confined to a single variety, have been restricted to the varieties in the Inner Circle. The test should expose the examinees to more varieties to ‘foster their sociolinguistic awareness and sensitivity’ (Hu, Reference Hu, Aslagoff, McKay, Hu and Renandya2012: 136; Brown, Reference Brown2004; Kachru, Reference Kachru and Hinkel2011). The local variety, Chinese accent, can be a fair candidate. Studies (e.g. Harding, Reference Harding2012) have indicated that Chinese students could be advantaged when taking listening assessment recorded by proficient Chinese-accented speakers. Indeed, the CET test-takers typically have much and even more exposure to the Chinese accent (e.g. learning English with teachers who share their L1) than other accents (He & Zhang, Reference He and Zhang2010).

A recommended way to diversify the topic and accent selection discussed above is sample more from local English media, such as China Central Television (CCTV)-News (a local English TV channel), and China Daily and Beijing Today Weekly (local English newspapers). Take China Daily (see http://global.chinadaily.com.cn/) as an example. It covers a wide range of global (including the Inner Circle) and local topics (e.g. World, China, Technology, Business, Culture, Travel, and Sports) that are closely relevant to Chinese people. One of the latest articles from ChinaDaily-Opinion discussing a popular topic in China – ‘Food waste is a shameful chronic disease’ – can be a potential Reading material. Another hot topic – ‘Should mukbanger, or Chibo be banned?’ – could be adapted for the writing or speaking test, with a slight modification by adding a brief explanation of the term ‘Mukbanger’.Footnote 8 In addition, the newspaper uses a combination of NNS and NS journalists that compose for both global and local audiences and is a source of the local variety, China English.

Conclusion

As a local standardized language proficiency test (LSLPT) in China, the College English Test (CET) demonstrates impacts of the WEs paradigm from various aspects, which contributes largely to the conversation of WEs and LT. Given the time-honored concerns such as insufficient codification and stakeholders’ unacceptance of any new varieties as well as the entrenched NS-model in English education in China, the CET still uses the Inner Circle Standard as the underlying standard and construct, which is shown in the reliance on Inner Circle topics and accents in the selected-response items. However, the test has relaxed this standard to a large extent, by including global and local elements in the selected-item materials, focusing on global and local topics in the constructed prompts, and decentering the assessment of NS formal accuracy by avoiding discrete-point items and emphasizing communicative competence at all linguistic levels in the scoring. Different from traditional LT practices, the test also references the local variety when defining intelligibility, acceptability, and appropriateness in its scoring criteria.

Concerning the limitations of the test under the WEs framework, the study also proposed possible modifications to the Listening, Reading, and Writing tests, namely sampling more from local English media to add diversity and relevance to topic and accent selection. The modifications will address the local validity and bias issues attached to the restriction to the Inner Circle context that has little relevance to the Chinese context and make the assessed construct more comprehensive.

Due to the scope of the study, more research can be done in the future. First, the study only examined the scoring rubrics and sample responses in the test specification; research on rater behavior based on real response data in the Writing, Translation, and Speaking assessments would inform us of how scoring practices are related to the WEs paradigm. Besides, it would be helpful to conduct a more elaborate text analysis on the linguistic features of the test input and the vocabulary list in the specification to learn more about the underlying linguistic norms in the test. Additionally, it would be interesting to examine other LSLPTs in China, such as the Test for English Majors (TEM) and National College Entrance Exam (NCEE), and similar LSPTs in other nations, such as the National English Ability Test (NEAT) in South Korea, to enhance our understanding of language testing in the Expanding Circle context.

Nevertheless, the study could shed light onto how LSLPTs like the CET in the Expanding Circle context can benefit from the WEs paradigm and in what ways such tests can incorporate the advocacies by the WEs research into practice to better serve its local examinees under the dynamic sociolinguistic reality. Of course, more research on WEs in general, especially data-driven empirical studies such as those sufficiently codifying the varieties in the three circles, need to be done (e.g. Davies et al., Reference Davies, Hamp–Lyons and Kemp2003; Brown, Reference Brown2014) in order to lay a more solid foundation for the conversation with LT and to dissolve more practicality issues.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Dr. Margie Berns (Purdue University) for her supervision of the study as the final project of her World Englishes course, her encouragement to send the paper to English Today for publication, and an insightful discussion on the revision of the paper. I also thank Zijie Wu (Purdue University) for his efforts in checking the coding of the data and a helpful discussion of improving the coding.

Appendix I: Structure of the College English Test (CET)

Table 1.1: CET-4 (Specifications, 2016: 5)

Table 1.2: CET-6 (Specifications, 2016: 7–8)

Table 1.3: CET-SET4 (Specifications, 2016: 7)

Table 1.4. CET-SET6 (Specifications, 2016: 9)

Appendix II: Sample coding

Table 2.1 Sample coding for the Listening Section

Table 2.2: Sample coding for the Reading section

QIUSI ZHANG is a PhD student in Second Language Studies at Purdue University. She is currently a testing office assistant and tutor at the Oral English Proficiency Program (OEPP). Her past work experiences include teaching English as a foreign language in China for four years and teaching the first-year composition course at Purdue for two years. Her research interests include world Englishes, second language testing and assessment, second language acquisition and development, and corpus linguistics. Email: [email protected]

QIUSI ZHANG is a PhD student in Second Language Studies at Purdue University. She is currently a testing office assistant and tutor at the Oral English Proficiency Program (OEPP). Her past work experiences include teaching English as a foreign language in China for four years and teaching the first-year composition course at Purdue for two years. Her research interests include world Englishes, second language testing and assessment, second language acquisition and development, and corpus linguistics. Email: [email protected]