Twin studies are a valuable resource for epidemiological and genetics research. They enable the identification of genetic and environmental contributions to individual variation in complex traits and diseases (Hur & Craig, Reference Hur and Craig2013). Many countries, predominantly in Europe, North America and Asia, have established twin registries to facilitate the investigation of a wide range of aspects of human health and behavior (Bjerregaard-Andersen et al., Reference Bjerregaard-Andersen, Gomes, Joaquím, Rodrigues, Jensen, Christensen and Sodemann2013; Ferreira et al., Reference Ferreira, Oliveira, Junqueira, Cisneros, Ferreira, Murphy and Teixeira-Salmela2016; Hur & Craig, Reference Hur and Craig2013; Marcheco-Teruel et al., Reference Marcheco-Teruel, Cobas-Ruiz, Cabrera-Cruz, Lantigua-Cruz, García-Castillo, Lardoeyt-Ferrer and Valdés-Sosa2013). However, there is a dearth of studies in admixed populations, which exhibit distinct genetic architectures due to their complex history of genetic admixture and being subjected to distinct environmental factors.

Historically, research in genetics has been primarily focused on populations of European ancestry. For instance, genomewide association studies (GWAS) have greatly improved our understanding of the genetic basis of complex diseases, such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis or type 2 diabetes, over the last decade (Bustamante et al., Reference Bustamante, Burchard and De la Vega2011; Need & Goldstein, Reference Need and Goldstein2009; Popejoy & Fullerton, Reference Popejoy and Fullerton2016). However, as of 2009, 96% of participants in GWAS studies were of European descent, while Hispanic and Latinos represented only .06%. By 2016, the proportion of individuals of non-European descent had increased to nearly 20%, mainly due to more studies being conducted in populations of Asian ancestry (Popejoy & Fullerton, Reference Popejoy and Fullerton2016), but admixed populations, Hispanic and Indigenous people are still, to date, underrepresented. In the long run, a lack of representation might result in inequitable access to the benefits of precision medicine, exacerbating existing disease and healthcare disparities (Martin et al., Reference Martin, Kanai, Kamatani, Okada, Neale and Daly2019; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Kuchenbaecker, Walters, Chen, Popejoy, Periyasamy and Duncan2019; Wojcik et al., Reference Wojcik, Graff, Nishimura, Tao, Haessler, Gignoux and Carlson2019)

The heritability of a trait, that is, the amount of variance of the trait that can be attributed to genetic factors, is a population-specific parameter. For instance, the heritability of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms has been estimated at 14% in individuals of European ancestry (Otowa et al., Reference Otowa, Hek, Lee, Byrne, Mirza, Nivard and Hettema2016); however, a recent study in a sample of Hispanic participants living in the USA showed a heritability of 7.2% (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Sofer, Gallo, Gogarten, Kerr, Chen and Smoller2017), suggesting that dissimilar genetic influences are in place. The question still remains whether similar heritability estimates will be identified for Hispanic populations living in environmentally diverse countries of Latin America.

Advantages of integrating diverse populations in genetic association studies include the possibility for uncovering novel population-specific genetic variants implicated in disease and drug response (Mills & Rahal, Reference Mills and Rahal2019) and aiding in the fine mapping of disease risk loci (Gonzalez et al., Reference Gonzalez, Gupta, Villa, Mallawaarachchi, Rodriguez, Ramirez and Escamilla2016). Therefore, there is growing interest among the scientific community in increasing ethnic diversity in genetic studies. To that end, establishing population-based deeply phenotyped and genotyped cohorts in Latin America is a paramount step.

Mexico is culturally and ethnically diverse. Its population has a complex admixed genetic makeup, with contributions from European, Native American and African and, to a lesser degree, East-Asian ancestry populations (Moreno-Estrada et al., Reference Moreno-Estrada, Gignoux, Fernández-López, Zakharia, Sikora, Contreras and Bustamante2014). Similarly, genetic stratification among Indigenous populations within Mexico is striking, with some groups being as differentiated as Europeans are from East Asians (Moreno-Estrada et al., Reference Moreno-Estrada, Gignoux, Fernández-López, Zakharia, Sikora, Contreras and Bustamante2014). Thus, twin studies in the Mexican population could contribute substantially to our understanding of the genetic and environmental mechanisms that underlie ethnic variation in complex traits and diseases, including metabolic, cardiovascular and mental diseases, or behavioral, psychometric and anthropometric traits. This reasoning is what inspired the creation of TwinsMX, a population-based registry of Mexican twins.

TwinsMX was founded in 2018 as a national twin registry in Mexico, with the electronic questionnaires portal opening for registrations in May 2019. Its primary aim is to establish one of the largest deeply phenotyped population-based cohort studies with a genetically informative design in an admixed population. The core research team is multidisciplinary, comprising experts in bioinformatics, psychology, neuroscience and genetics. The required infrastructure and institutional support has been provided by National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), the premier research university in the country, and technical advisory during the creation process was facilitated by Mexican geneticists working with the Queensland Twin Registry in Brisbane, Australia. Collaborations with other twin registries in Latin America and around the world are underway. TwinsMX will contribute significantly to expand our knowledge of the genetics of admixed populations and will lay the foundations for a larger national longitudinal biobank with associated genotyping and biological samples in the future.

Experimental Design and Progress to Date

Target Population and Estimates

Our target population consists of twins, triplets and members of any multiple births from all over Mexico. Data from Mexico’s National Statistics and Geography Institute (INEGI, in Spanish) indicate that there are approximately 750,000 twin-pairs aged between 18 and 60 in the country. In a first stage, the goal of TwinsMX is to recruit 15,000 individuals (~7500 twin-pairs). Official data from the National Intercensal Survey of 2015 indicate that the State of México, Mexico City, Veracruz, Jalisco, Puebla and Guanajuato are the states with the highest number of inhabitants, with 13.5%, 7.5%, 6.8%, 6.6% and 4.9% of Mexico’s total population, respectively (INEGI, 2015). These states are geographically located within the central region of the country, and thus is where we are focusing our initial recruiting efforts.

Recruitment Strategy

Participants are being invited via social media (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram) and traditional advertising to engage and participate. We aim to reach the twin and multiple birth population nationwide by actively sharing digital content as part of our publicity campaign. Furthermore, TwinsMX has been featured in radio shows and interviews where members of our research team have been broadcast in national media, giving us the opportunity to talk about the purpose and goals of the project. Notably, an alliance has been established with the National Multiple Births Association, and the official launch of the registry was made at their annual meeting this year. As part of our strategy to recruit a diverse cohort of participants and to promote the project in different regions, we will host information events across the country.

Ethics Approval and Privacy Protection

The project has been reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Institute of Neurobiology at UNAM in March 2019. Participant registration and data collection are done online through a secure page, and the personal information of all participants is anonymized and stored in a database within a dedicated server at the National Laboratory of Advanced Scientific Visualization at UNAM, under strict security protocols. As declared in the ethics approval, informed consent must be obtained from every participant in the project. New registrations cannot be completed until the participant provides his digital signature granting consent on the use of his or her data. In compliance with the Federal Law on the Protection of Personal Data Held by Private Parties, TwinsMX has a privacy statement that stipulates how personal data will be used, stored and handled, and how users are protected under principles provided by the Mexican federal law.

Institutional Identity and Online Presence

Our logo (Figure 1) consists of the words ‘Twins’ and ‘MX’, and ‘Mexican Twin Registry’ (in Spanish, ‘Registro Mexicano de Gemelos’), located right below. The ‘I’ in the word ‘Twins’ and the ‘X’ in the ‘MX’ simulate two heads and bodies, making reference to twin-pairs. The color scheme, including bright green and pink, was chosen because they both represent the vibrancy of our culture, as well as the charisma of our people. Mexicans regard that specific tone of pink as ‘Mexican pink’. Along with the green, these colors have been used in traditional Mexican clothing, textiles and artisanal objects and, therefore, resemble the Mexican spirit and its people. The TwinsMX logo is currently under the registration process as a trademark and securing copyrights related to its exclusive use and distribution within the Mexican territory.

Fig. 1. TwinsMX logo: The Mexican Twin Registry (‘Registro Mexicano de Gemelos’ in Spanish).

Our website was designed in accordance with the same color scheme used in the logo. Additionally, it features photographs from twins and multiple birth members at an event hosted by the National Multiple Births Association in Jalpan, Querétaro, where we officially launched the project and began recruiting participants. The site features two buttons that redirect potential participants to the registration page and surveys implemented in the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform (Harvey, Reference Harvey2018; Wright, Reference Wright2016). The site includes an ‘About Us’ (‘Acerca de’ in Spanish) section, links to the privacy statement and ‘Frequently Asked Questions’. Furthermore, the site has a ‘Contact Us’ button that displays a map with the location of our laboratory at UNAM in Querétaro, our contact information and a message box that allows visitors to get in touch with our research team. Finally, we also have a presence in social networks, including Facebook, Twitter and Instagram; people can find us under ‘/TwinsMXOfficial’ and follow us for news and updates about the project and general information including posters, infographics and photos that stir continuous interaction with the general public.

Data Collection Platform

Data collection has been conducted using the REDCap platform (Harvey, Reference Harvey2018; Wright, Reference Wright2016), which enables the integration of several surveys and document collections in research studies while facilitating data management for statistical analysis.

In compliance with Article 55 of the Federal Civil Code in our country, all Mexicans have the legal obligation to register the birth of their children within 6 months following the date of birth of each child born in Mexico. All registered Mexicans are assigned a Unique Population Registry Code (CURP, for the abbreviation of Clave Única de Registro de Población, in Spanish), composed of 18 alphanumeric characters that contain initials and an additional letter from their given and family names, date of birth, sex, state of birth, and a unique number to avoid duplication.

Each participant in TwinsMX is required to enter their CURP as part of their registration process. Given that this code is unique, users can use it as their username in the platform and is used to match twins to their co-twin. This allows participants born and registered in Mexico, but currently living abroad, to participate if they have a CURP. Importantly, the number can only be used by participants to access their information, because data are anonymized in the backend.

Measures Being Collected

Data collection surveys are structured into two modules (for an overview of contents, see Tables 1 and 2). We have implemented a set of initial surveys about medical family history, zygosity, sociodemographic information, personality, addictions, mental health, eating habits, lifestyle and quality of life variables, validated in the Mexican population. Also, cognitive tests that assess essential cognitive processes, including attention, working and episodic memory, decision-making and impulsivity, are being integrated in the platform. Some of these tasks and questionnaires have previously been used in the Mexican population by Dr Ruiz-Contreras (Ruiz-Contreras et al., Reference Ruiz-Contreras, Soria-Rodríguez, Almeida-Rosas, García-Vaca, Delgado-Herrera, Méndez-Díaz and Prospéro-García2012) and Dr Alcauter (Alcauter et al., Reference Alcauter, García-Mondragón, Gracia-Tabuenca, Moreno, Ortiz and Barrios2017; Gracia-Tabuenca et al., Reference Gracia-Tabuenca, Moreno, Barrios and Alcauter2018). Participants are asked for permission to be recontacted in the future, to be invited to take part in additional waves of the study and indicate their willingness to provide a DNA sample for genotyping.

Table 1. Overview of the contents in the core module

Table 2. Overview of the contents in the secondary module

Recruitment to Date

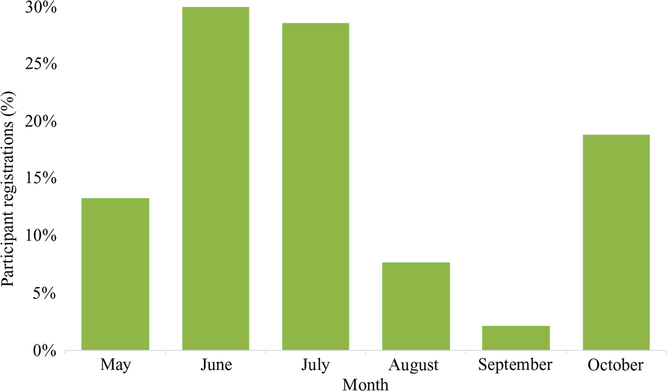

The TwinsMX platform was launched in May 2019. Since then, 145 individuals had successfully signed up as of October 18, 2019 (Figure 2). Of those, 51% of registered participants are male and 49% are female; 49% self-reported being monozygotic pairs, 45% dizygotic and 6% do not know (Figure 3). We observed an increase in registration numbers from June to July when the research team attended the biggest twin and multiple birth events nationwide. From then on, we had a considerable decrease in numbers from August to September, which led us to launch an improved social media strategy to strengthen our positioning, which resulted in an increase in the number of online registrations during October (Figure 2).

Fig. 2. Monthly registrations since launching the TwinsMX platform in May 2019 (as of October 18, 2019).

Fig. 3. Self-reported zygosity of registered twin-pairs (as of October 18, 2019).

Most registered participants to date come from the state of Querétaro, followed by Mexico City, San Luis Potosí, Jalisco, Guanajuato, Veracruz and the State of Mexico (Figure 4a). Considering the distribution of multiple births across the country (Figure 4b), we believe this trend to be biased by the fact that part of our core research team and the National Multiple Births Association in Mexico are both based in Querétaro, where we have a stronger presence. Nonetheless, we have successfully managed to reach all states across the country via social networks.

Fig. 4. (a) Geographical distribution of multiple births in Mexico by State, shown by quintiles (National Institute of Statistics and Geography, ‘Birth characteristics’, press communication, 2017) and (b) TwinsMX incoming participant registrations as of October 2019.

Available Infrastructure and Support

UNAM provides full infrastructure and institutional support for the development and upkeep of TwinsMX as Mexico’s National Twin Registry. Our core research team is based in both the main campus in Mexico City (School of Psychology at University City) and a satellite campus in the city of Querétaro (International Laboratory for Human Genome Research and Institute of Neurobiology), located 221 km north-west of Mexico City. Similarly, facilities such as the Unit for Magnetic Resonance Imaging and the National Laboratory of Advanced Scientific Visualization from the UNAM also provide infrastructure and regular support to our twin registry.

Collaborations

Technical advisory and support during the creation of this twin registry was facilitated by Mexican geneticists working with the Queensland Twin Registry in Brisbane, Australia (Dr Rentería and Dr Cuéllar-Partida), and budding collaborations with other twin registries in Latin America and around the world are underway. Furthermore, the connection with the National Multiple Births Association in Mexico has been extremely valuable and has allowed us to get closer to the community of multiple births.

Future Directions

As there is only a handful of deeply phenotyped population-based cohorts with genetically informative designs in Latin America, we expect that TwinsMX will play a central role in characterizing the genetic and environmental factors involved in complex traits and diseases in admixed populations. In parallel, we will try to secure funding for DNA collection, genotyping, and to extend the study to include family members of twins, such as parents and siblings. We envision that molecular genetic studies in the Mexican population will provide valuable data for fine mapping of genetic risk variants relevant for many conditions.

A particular interest of the research team is to investigate brain structure and function through magnetic resonance imaging technologies, taking advantage of state-of-the-art facilities available within the National Laboratory of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (Laboratorio Nacional de Imagenología por Resonancia Magnética in Spanish) at the Institute of Neurobiology. Neuroimaging twin studies have been fundamental in understanding the heritability and genetic architecture of brain structure and function (Gao et al., Reference Gao, Elton, Zhu, Alcauter, Smith, Gilmore and Lin2014; Jansen et al., Reference Jansen, Mous, White, Posthuma and Polderman2015; Rentería et al., Reference Rentería, Hansell, Strike, McMahon, de Zubicaray, Hickie and Wright2014). In addition, the electrophysiological brain activity evaluated at the School of Psychology will also provide insights about temporal information related to cognitive function. Therefore, there is potential to investigate the genetic relationships of neuroimaging and electrophysiological measures in relation to specific conditions (e.g., addiction, psychiatric disorders, metabolic or cardiovascular conditions).

Overall, we also hope to articulate a network of collaborations with other scientists in Mexico and to actively contribute to the larger international community of genetics consortia. We have already established contact with the Mexican Biobank Project (http://mxbiobankproject.org/), a group of researchers that have already established strong genotyping and analysis pipelines for the Mexican population. Thus, we extend an invitation to all those with common interests to get in contact with us and explore opportunities for collaboration.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México for their support for this project and to all the twins who have signed up for their willingness to participate and contribute to medical research. We thank Prof Nick Martin of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute for valuable input and feedback during the early stages of the creation of the registry; Mauricio Guzman for designing the logo and corporate image for TwinsMX; Patricia Andrade for her support as marketing strategy advisor; the staff responsible for the maintenance of the TwinsMX IT infrastructure, in particular Luis Alberto Aguilar Bautista and Jair García Sotelo at the Laboratorio Nacional de Visualización Científica Avanzada (Mexico); those who have supported us in the selection of surveys and instruments, Dr Luis Pablo Cruz-Hervert from the School of Odontology at UNAM, and Dr Carlos S. Cruz-Fuentes and Dr Gabriela A. Martínez-Levy from Mexico’s National Institute of Psychiatry; those that contributed to editing the questionnaires for REDCap: Elissa López, Carla Guillermo-Flores, Angela Polo, Alejandra Lázaro, Andrea Tapia and Sofía Pradel. We especially thank Asociación de Nacimientos Múltiples de México, A.C., particularly Pedro Alfonso Ochoa Ledesma, President of the Association, who has supported the project from the beginning.

Financial support

A.M.-R.’s laboratory is supported by funding from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia, Mexico (CONACYT) (Grant no. 269449) and by a grant from the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (PAPIIT-UNAM; Grant no. IA206517-IA201119); A.E.R.-C.’s laboratory is supported by PAPIIT-UNAM (Grant no. IN217918). S.A. is supported by PAPIIT-UNAM (Grant no. IA204217, IN212219). G.C.-P. is funded by an Australian Research Council (ARC) Discovery Early Career Researcher Award (DE180100976). M.E.R. thanks the support of Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council and the SRC, through a National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC)-ARC Dementia Research Development Fellowship (GNT1102821).