Introduction

Forensic hospitals in Canada use three forms of restraint when patients pose a risk of harm to self or others: (1) chemical, (2) physical, and (3) environmental. The environmental category, known in the medical community as “seclusion,” involves placing patients in a secure room that is locked from the outside. These rooms are often like a jail cell: small in size, windowless (except for an observational portal in the door), empty (except for a mattress and possibly a toilet), containing no control over the lights or temperature, and isolating.Footnote 1 This article analyzes the legal regulation of seclusion in forensic hospitals in Canada, particularly in comparison to the practice of solitary confinement in prisons.

In the penal context, at least historically, the legal system failed to control the isolation of prisoners.Footnote 2 Over the past ten years, however, Canadian courts have grappled with the legality of prolonged solitary confinement in prisons.Footnote 3 Under the Mandela Rules, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, solitary confinement is defined as “the confinement of prisoners for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact.”Footnote 4 Solitary confinement becomes “prolonged” when it is longer than fifteen consecutive days. Prolonged solitary confinement is prohibited for prisoners and solitary confinement of any length is prohibited for prisoners with mental disabilities if such confinement would exacerbate their disability.Footnote 5 Canadian courts now accept that the Mandela Rules represent “an international consensus of proper principles and practices in the management of prisons and the treatment of those confined.”Footnote 6

Based in part on this consensus, two appellate courts recently found federal legislation authorizing prolonged solitary confinement unconstitutional on the basis that such detention is “grossly disproportionate” and “cruel and unusual.”Footnote 7 The Government of Canada initially responded by appealing the rulings that invalidated legislation authorizing prolonged solitary confinement, but abandoned those appeals in favour of passing new legislation to purportedly end solitary confinement and replace it with a constitutionally compliant “structured intervention unit” regime.Footnote 8 The new scheme is subject to an ongoing Charter challenge.Footnote 9 Notwithstanding these concerns, litigation to end prolonged solitary confinement in prisons was successful in establishing that such confinement is unconstitutional and achieving judicial recognition that prolonged isolation is harmful. These are not small victories.

The harmful effects of solitary confinement have now been “accepted by every Canadian judge who has seriously considered the issue.”Footnote 10 Building on this recognition of harm, several class action lawsuits were instigated, pursuing damages for people with serious mental illnesses who were placed in solitary confinement for any length of time.Footnote 11 Focusing on people with serious mental illnesses as a class enabled courts to extend what is known about the harms of solitary confinement to this particularly vulnerable group. In 2020, the Ontario Court of Appeal held “that from the late 2000s it was widely recognized and accepted that placing inmates suffering from mental illness into solitary confinement caused them serious harm and therefore should be avoided.”Footnote 12 In 2021, the same court went further, holding that placement of inmates with serious mental illnesses in solitary confinement for any period of time violates their constitutional rights to life, liberty, and security of the person, and to be free from cruel and unusual treatment or punishment.Footnote 13

The story of this litigation is one of enhanced constitutional scrutiny of solitary confinement conditions in Canadian prisons, especially for prisoners with mental illnesses. These gains, however, have not translated into comparable scrutiny of seclusion and isolation in forensic hospitals. This article examines that disjuncture. Part I discusses the objective and subjective harms associated with human isolation in the penal and hospital contexts, and shows that these harms are comparable in both contexts. Based on a series of access-to-information requests for hospital seclusion policies across Canada, Part II analyzes the existing regulatory framework for seclusion and explains why the scrutiny of solitary confinement that courts have provided has not transferred to seclusion in the hospital context. Part III proposes three legal avenues to achieve enhanced legal scrutiny of seclusion. The article argues that case law on prolonged solitary confinement in the penal context has application to the forensic psychiatric context and that a failure to more closely regulate the use of seclusion may render this type of mental health legislation and treatment unconstitutional.

I. The Harms of Human Isolation

1. Solitary Confinement in Prisons

Beyond positive outcomes, Canadian solitary confinement litigation is remarkable for its detailed recognition of both the subjective and objective psychological harm caused by solitary confinement and for the willingness of courts to place greater emphasis on the risk of such harms to prisoners ahead of governmental arguments about prison security.

In terms of objective harm—assessed by third-party professionals using accepted clinical standards—courts have found that prolonged solitary confinement “can and does cause physical and mental harm, particularly to inmates that have serious pre-existing psychiatric illness.”Footnote 14 Examples of this type of harm include: “anxiety, withdrawal, hypersensitivity, cognitive dysfunction, significant impairment of ability to communicate, hallucinations, delusions, loss of control, severe obsessional rituals, irritability, aggression, depression, rage, paranoia, panic attacks, psychosis, hopelessness, a sense of impending emotional breakdown, self-mutilation and suicidal ideation and behaviour.”Footnote 15 These harms can occur within forty-eight hours of being isolated and can be permanent.Footnote 16 On the basis of these objective harms, which have been characterized as “a consistent stream of medical opinion,” courts have found it necessary to impose a firm cap on the use of solitary confinement for ordinary prisoners and an outright prohibition for prisoners with serious mental illnesses.Footnote 17

In terms of subjective harm—assessed by self-reports from people with lived experience—courts have found that prisoners experience the isolation of solitary confinement “very negatively and stressfully.”Footnote 18 Prisoners report experiencing “anger, hatred, bitterness, boredom, stress, loss of the sense of reality, suicidal thoughts, trouble sleeping, impaired concentration, confusion, depression and hallucinations.”Footnote 19 Where isolation is prolonged, “prisoners who are denied normal social contact with others […] experience heightened levels of anxiety, increased risk of panic attacks and a sense of impending emotional breakdown.”Footnote 20 In Francis v Ontario, the trial court admitted several affidavits from prisoners who described their emotional experience upon being placed in solitary confinement.Footnote 21 While reliance on this subjective experience was perhaps unnecessary, it appears to have played a role in the intensity of judicial scrutiny of solitary confinement.

These types of objective and subjective factual findings are not remarkable when viewed against the extensive scientific literature documenting the psychological harms of solitary confinement.Footnote 22 However, when viewed against a long history of treating prisons as black boxes, shielded from theoretical and legal scrutiny, the judicial willingness to accept and engage with these facts is notable.Footnote 23 What is even more remarkable is that courts then gave these harms lexical priority over other competing interests (e.g. prison security) in their constitutional proportionality analysis.

Canadian constitutional law employs proportionality or balancing both at the rights violation stage (for some rights) and at the infringement justification stage. In the context of the deprivations of the right to life, liberty, or security of the person, claimants must show that interference with the right is also not in accordance with one or more principles of fundamental justice. One principle of fundamental justice is that against “gross disproportionality,” which applies in extreme cases where the interference with the right is “totally out of sync” with the objective of the law in question.Footnote 24 In the context of cruel and unusual treatment, excessive punishment is one track or avenue through which a violation can be found.Footnote 25 Punishment will be excessive when it is incompatible with human dignity and shows “complete disregard for the specific circumstances of the sentenced individual and for the proportionality of the punishment inflicted on them.”Footnote 26 In operationalizing what is excessive, the Supreme Court of Canada has adopted the language of “gross disproportionality” and called for a contextual and comparative analysis that examines the impact of the punishment in relation to the objective of the law.Footnote 27

In comparing judicial approaches to these two rights, we see two important features: first, substantial analytical overlap between the notion of gross disproportionality compromising the principles of fundamental justice and operationalizing what constitutes excessive treatment or punishment; and second, reliance on “context” to determine what is outside acceptable constitutional boundaries. This second feature invites judicial discretion that makes case outcomes turn on how particular judges view the specific circumstances.

One explanation for the success of solitary confinement litigation in Canada is the incontrovertible evidence of its harm.Footnote 28 As one judge put it recently, solitary confinement is a “dungeon inside a prison.”Footnote 29 But this harm only becomes disproportionate if judges are prepared to recognize the human dignity of prisoners as something that requires prioritization relative to state interests. The fact that courts were willing to recognize these dignity interests in carceral settings is what makes these cases truly remarkable, even if it has not ended solitary confinement in practice. Such recognition grants standing to people who are subjected to isolation even though they have themselves transgressed socially by violating criminal law. This empowers incarcerated people to demand responsive justifications or systemic change from the state.

2. Seclusion in Forensic Hospitals

Unlike in prisons, there is no hard cap on the length of seclusion in Canadian forensic hospitals or prohibition on the use of such treatment for people with serious mental illnesses. Before discussing the use and impact of seclusion as an intervention in forensic hospitals, it is important to distinguish between the ordinary or constitutional meaning of “treatment” and the medical meaning of “treatment.”

Constitutionally, the Supreme Court of Canada has not definitively determined the meaning of “treatment” but has opined that it is a “process or manner of behaving towards or dealing with a person or thing.”Footnote 30 Detention for non-punitive reasons, transfer to segregation, and detention conditions such as lockdowns, have all been found to constitute a “treatment” for the purposes of determining whether state action was cruel and unusual.Footnote 31

Medically, the meaning of “treatment,” if it is discussed at all, arises in conversations about consent. The common law recognizes a right to be free from non-consensual “medical treatment” but does not define that term.Footnote 32 The ordinary use of the word “treatment” means care provided to a patient in response to illness or injury. Some provincial health statutes do define “medical treatment.” For example, the Ontario Health Care Consent Act defines “treatment” as “anything that is done for a therapeutic, preventive, palliative, diagnostic, cosmetic or other health-related purpose, and includes a course of treatment, plan of treatment or community treatment plan.”Footnote 33 What is common to all of these statutory articulations of “medical treatment” is the requirement that the treatment should assist the patient in some way, even if that assistance is merely cosmetic.

Historically, seclusion was considered to be a medical treatment that would assist the patient. Indeed, seclusion was often referred to as “therapeutic quiet,” which implies that it was of some benefit to the patient.Footnote 34 In a survey of British physicians in 2001, 56 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that seclusion was a treatment that could benefit patients, whereas 33 percent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that seclusion was therapeutic.Footnote 35 Psychiatric literature from that period acknowledged there was no “inherent therapeutic property in the seclusion room itself” but contended there could be some theoretical benefit from the related isolation, containment, sensory deprivation, or punishment of the patient.Footnote 36 More recently, the therapeutic nomenclature has been removed in many jurisdictions and the isolation of patients is simply referred to as “seclusion.” Even if seclusion is not considered therapeutic, the Canadian Psychiatric Association maintains that seclusion is a legitimate intervention that may be used in emergency situations in which there is a “risk of physical harm to patients, staff, and copatients.”Footnote 37 Despite being part of accepted psychiatric practice in Canada, the harms of such seclusion and social isolation, particularly when viewed subjectively, are often comparable to those associated with solitary confinement.

In terms of objective harm, health professionals recognize that seclusion creates a significant risk of harm to people with mental illnesses, including “serious injury or death, retraumatization of people who have a history of trauma, and loss of dignity and other psychological harm.”Footnote 38 Multiple studies have linked placement in seclusion with increased risk of post-traumatic stress disorder.Footnote 39 These findings are not new. One of the first comprehensive literature reviews of the subject, published in 1994, concluded that it is “well-established that these procedures can have serious deleterious physical and (more often) psychological effects on patients.”Footnote 40 This parallels what Canadian courts have found was well established, by the late twentieth century, concerning the harms caused by solitary confinement in prisons.

Notwithstanding these harms, multiple studies have found that health professionals view seclusion as a coercive and unpleasant, but necessary, intervention to respond to violent patient behaviour towards self and others.Footnote 41 In this sense, seclusion is not a medical treatment even though it is ordered by medical professionals, but rather an administrative tool to control violent behaviour. Whether seclusion has any meaningful benefit from a clinical perspective is unclear. Mental Health America, a national nonprofit organization, takes the position that “[s]eclusion and restraints have no therapeutic value, cause human suffering, and frequently result in severe emotional and physical harm, and even death.”Footnote 42 Recent research on the ethical challenges of ordering seclusion found “no studies that definitively support the therapeutic effect of seclusion.”Footnote 43 As a result, there is a “major discrepancy between the widespread use of seclusion and its knowledge basis.”Footnote 44 Designing randomized–controlled trials to determine whether seclusion is ever beneficial to patients is complicated by the ethical difficulty (perhaps impossibility) of knowingly subjecting patients to a treatment that has such deleterious effects.Footnote 45 What this reveals is that seclusion is almost entirely an administrative practice in hospitals, not unlike administrative segregation in jails, that responds to real and perceived institutional management needs.

Like administrative segregation, the subjective harms associated with seclusion, while not universal, are also substantially negative.Footnote 46 Qualitative studies of patient experience report emotions of fear, shame, neglect, anger, humiliation, worthlessness, powerlessness, loss of control, and loneliness.Footnote 47 Even when there are policies in place to offer alternatives to seclusion and post-seclusion debriefing, patients in a non-forensic psychiatric hospital reported not being offered any alternatives to seclusion or post-seclusion debriefing.Footnote 48 Several patients, in multiple studies, reported feelings of being caged and treated like an animal.Footnote 49 As one patient explained: “the thing is, when they put people in TQ [therapeutic quiet], they don’t really treat them like people they treat them like an animal kind of thing.”Footnote 50 The result is feelings of abandonment, pain, violation, humiliation, and being punished.Footnote 51 A recent review study found three consistent themes in the closed psychiatric ward patient experience: (1) unclear information and application of rules, including in the context of seclusion; (2) lack of time and contact with nurses; and (3) feelings of humiliation.Footnote 52

For patients who have experienced social isolation in prison settings, the seclusion experience is often indistinguishable:

the seclusion experience reminded me of the time I was in a jail cell […] the seclusion forced me to revisit the bad experience I had in jail again […] the seclusion room had no “peep holes” like they have in the jail […] I thought how to get out of the room […] uh […] I mean […] uh […] if there was a ladder I would have climbed out of there.Footnote 53

Despite the similarities between the subjective harms reported by patients in seclusion and those of prisoners in solitary confinement, Canadian courts have not yet applied comparable constitutional scrutiny to what may be an equally harmful isolative experience.

II. The Legal Regulation of Seclusion

There are at least two reasons why seclusion has not been subjected to the same legal scrutiny as solitary confinement. First, there is no consistent legal framework that regulates seclusion in Canada. Many provinces have no law that governs seclusion at all. This means that oversight, to the extent that there is any, must come from the common law and a patchwork of policies, often overseen by administrative tribunals with limited access to review by courts. Second, within this regulatory patchwork, physicians are afforded substantial deference and physician-ordered social isolation is viewed as qualitatively different from jail-ordered solitary confinement.

The regulation of seclusion in forensic hospitals starts off on a promising note. Subsection 672.55(1) of the Criminal Code expressly authorizes Criminal Code Review Boards to order the detention of not criminally responsible (NCR) patients in forensic hospitals, but it also prohibits such boards from ordering specific treatment for an NCR patient without their consent.Footnote 54

In determining what level of detention order is required—for example, supervised day passes, unsupervised day passes, or overnight passes—the board may consider an NCR patient’s compliance with recommended medical treatment insofar as non-compliance is linked to the risk that the patient poses in the community. But the board cannot compel a patient to consent to a particular treatment. Beyond restricting the imposition of treatment without consent, the Criminal Code says nothing further about what treatment is acceptable in forensic hospitals. This silence is not an oversight and results from the fact that health, the operation of hospitals, and the regulation of health professionals are all provincial matters in Canada’s federal constitutional order.

The provincial jurisdiction over health means that seclusion, if it is to be regulated, must be regulated provincially. However, in the six provinces that were reviewed for this study (British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland & Labrador), only one province (Ontario) provides statutory authorization for seclusion and that authorization is only implied under a broader definition of “restrain.”Footnote 55 Other than stating that NCR patients may be restrained and including seclusion within the definition of restrain, the Ontario legislation is silent on when or how seclusion may be used.Footnote 56 The remaining provinces do not define or authorize seclusion by way of legislation or regulation (Table 1). Instead, these provinces rely on a patchwork of provincial or hospital-specific policies.

Table 1. Provincial Regulation of Seclusion by Legislation, Provincial Policy, and Forensic Hospital-Specific Policies in Six Canadian Provinces

* British Columbia defines “restraint” in its Health Care (Consent) and Care Facility (Admission) Act, RSBC 1996, c 181, but this legislation does not apply to forensic hospitals.

† Ontario defines “restrain” in its Mental Health Act, RSO 1990, c M.7, which also states that any NCR patient who is detained in a forensic hospital can be restrained.

To understand how seclusion is regulated in practice, the author submitted freedom-of-information requests for every major forensic hospital in six Canadian provinces: British Columbia, Alberta, Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland & Labrador. Only British Columbia had a provincial policy on the use of seclusion. The other provinces all had hospital-specific policies that applied to one or more forensic institutions (Table 1).

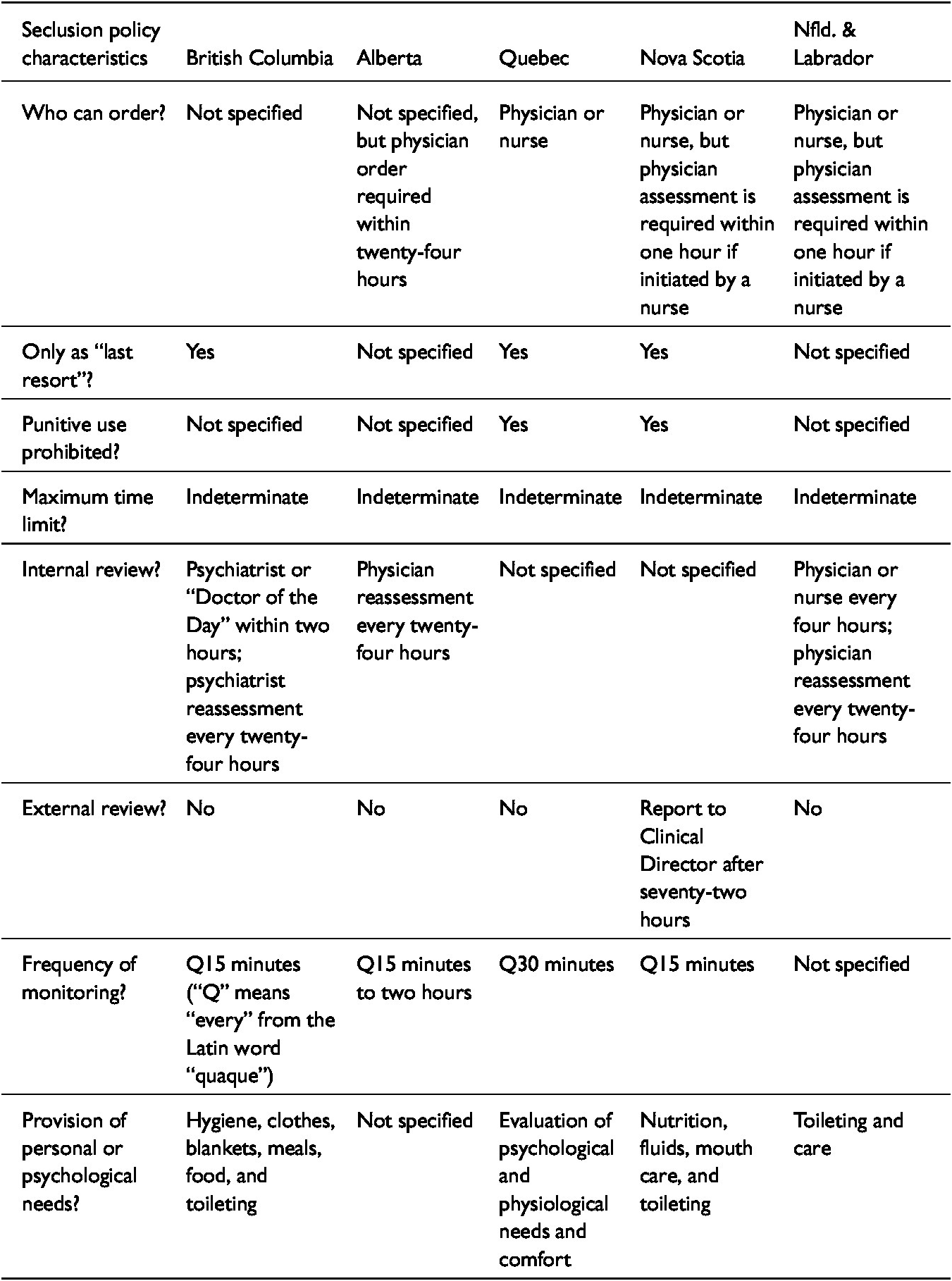

A comparison of the hospital-specific seclusion policies in five provinces (Table 2) as well as the seven hospital-specific seclusion policies from Ontario (Table 3) shows that there are both similarities and differences between the policies. Most policies permitted seclusion to be ordered by either a physician or a nurse and most required that seclusion should be used as a last resort. Roughly half explicitly precluded the use of seclusion as punishment.

Table 2. Comparison of Seclusion Policy Characteristics in British Columbia, Alberta, Quebec, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland & Labrador

Table 3. Comparison of Seclusion Policy Characteristics in Six Ontario Forensic Hospitals

All the policies permitted indeterminate seclusion. Like the prison administrative segregation schemes that were found to be unconstitutional, the policies do not expressly prohibit hospitals from isolating patients for more than twenty-two hours per day without meaningful human contact and for periods longer than fifteen days, contrary to the Mandela Rules.

Several policies implicitly envisioned that some placements in seclusion would last for longer than four weeks. This is evidenced by provisions of the policies that apply at the four-week mark. Internal review of the seclusion placement was required within anywhere between two hours and twenty-four hours. There were significant differences in when an external review was required. For the non-Ontario policies, only Nova Scotia had some form of external review after seclusion that lasted for longer than seventy-two hours and this was simply a report to the clinical director (Table 2). The Ontario policies, by contrast, employed a mixture of collegial review as well as review by physicians who were outside the treatment team; for prolonged placements in seclusion, in the range of seven to thirty days, most Ontario policies required some form of complex case assessment and notification of hospital management (Table 3).

Almost all the policies required some form of monitoring of the patient in seclusion with increased frequency at the beginning of the placement (Tables 2 and 3). Almost all the policies required that staff should provide basic hygiene and toileting opportunities to patients (Tables 2 and 3). Some specified that this should be outside the seclusion room, if possible, to protect the dignity of the patient; most permitted the use of bed pans, and one expressly prohibited the use of Styrofoam cups for toileting purposes. Only two of the twelve policies that were reviewed (17%) required staff to provide psychological counselling and support. None of the policies required patients in seclusion to be provided with meaningful human contact, but one of the twelve policies (8%) permitted family members and close others to visit a patient in seclusion with the permission of the treatment team. None of the policies required that patients should have daily time outside of the seclusion room or daily access to the outdoors. One of the twelve policies (8%) required daily bathing outside of seclusion but only if sufficient staff were available. This suggests that seclusion may often meet the definition of solitary confinement in the Mandela Rules or, at the very least, that seclusion akin to solitary confinement is not expressly prohibited by the policies.

One of the limitations of this type of study is that a written policy does not necessarily provide evidence of how the policy operates in practice. On-the-ground implementation of the policy could be better or worse than what is required. The principle of “last resort” could be fastidiously followed, limiting the quantum of seclusion placements. The internal and external review processes may function to limit lengthy stays in seclusion. Frequent patient monitoring may also provide more meaningful human contact than what is evidenced on paper. All of this could make seclusion work in practice quite differently from solitary confinement. Case law and available statistics cast doubt on this hopeful perspective.

In Re Edgar, for example, a patient who had been found NCR for mischief and resisting arrest was “detained in seclusion for over three years with little progress.”Footnote 57 During this time, the hospital obtained an internal and an external consultation from forensic psychiatrists pursuant to its policy on seclusion. The external psychiatrist recommended “relief from seclusion as frequently as possible in a safe manner.”Footnote 58 Before the provincial review board that was responsible for overseeing deprivations of liberty in forensic hospitals, the patient’s attending psychiatrist conceded that “there was not ‘an easy end in sight’ to his seclusion.”Footnote 59 This was exacerbated by the patient’s unwillingness to wear restraints when offered seclusion relief and the availability of non-oral antipsychotic medication.Footnote 60 Nonetheless, the review board found that there was no treatment impasse and no further supervisory responsibilities were needed. The Ontario Court of Appeal dismissed the patient’s appeal, concluding that the board’s determinations were reasonable even though the patient had “not made any progress” in the four years he had been detained at hospital.Footnote 61 As a result, no judicial constraints were placed on the prolonged use of seclusion in this case.

In Re McFarlane, the provincial review board found “any seclusion, with or without seclusion relief, is a significant restriction of the liberty of a person.” However, the board also concluded that its jurisdiction to review deprivations of liberty required a significant change to a patient’s liberty. The board reasoned that it was not compelled to review continuations of seclusion, prolonged or otherwise, that continued the same level of restricted liberty.Footnote 62 As a result, the board declined to review a two-and-a-half-month period of seclusion that started on the final day of a separate two-week seclusion period.Footnote 63

As part of this study, one province (British Columbia) provided seclusion statistics that also raise serious concerns. What is notable and commendable about these statistics is that they are being gathered as part of province-wide efforts to reduce the frequency and duration of seclusion. These statistics track the number of seclusion placements and the duration of those placements. In the 2019/20 fiscal year in British Columbia, 9 percent of patients (n = 67) were placed in seclusion for up to six hours, 17 percent (n = 131) for seven to twelve hours, 18 percent (n = 135) for thirteen to twenty-three hours, and 41 percent (n = 305) for one to five days. Nine percent of patients (n = 72) were placed in seclusion for six to fifteen days and 9 percent (n = 40) for more than fifteen days. In the 2020/21 fiscal year in British Columbia, 9 percent of patients (n = 9) were placed in seclusion for up to six hours, 28 percent (n = 27) for seven to twelve hours, 18 percent (n = 17) for thirteen to twenty-three hours, and 29 percent (n = 28) for one to five days. Eight percent of patients (n = 8) were placed in seclusion for six to fifteen days and 7 percent (n = 7) for more than fifteen days.Footnote 64

These statistics reveal that, in British Columbia, one or two out of every twenty patients (5–10%) are subjected to prolonged seclusion for a period in excess of fifteen days. Viewed in comparison with judicial findings about prolonged solitary confinement in prisons—specifically that such treatment is cruel and unusual—the prevalence of equivalent prolonged seclusion in hospitals is startling.

In discussing how solitary confinement was permitted to go unchecked for so long, Kerr highlights the role of administrative discretion and delegated authority to prison officials. Such delegated decision-making is part of the administrative state and so must conform to legal standards that, if not met, are actionable. But the existence of delegation and discretion often means that decision-makers are immunized in practice from effective judicial review. As a result, “[r]egimes that determine the character and quality of incarceration are often designed and implemented in a setting that can be characteristically unconstrained by the larger framework.”Footnote 65 Part of the undoing of solitary confinement, according to Kerr, was external critique of the policies that prison officials developed pursuant to their delegated authority.Footnote 66

There are good reasons to advance similar critiques of provincial and hospital seclusion policies. These policies permit indeterminate isolation of people with serious mental illnesses, often under conditions that are akin to solitary confinement, and with minimal oversight. But, unlike prison policies, hospital policies are implemented and overseen by physicians. Physicians hold a different place of trust in society and have substantially greater expertise than prison officials. Even though seclusion is associated with serious risks of objective and subjective harm, the fact that it is physicians who are overseeing the use of seclusion may immunize such policies from judicial scrutiny.

Not everyone is convinced that this immunity will last. Recently, Chaimowitz—the psychiatrist who authored the Canadian Psychiatric Association’s position statement on seclusion—reviewed the legal developments in solitary confinement litigation. He then queried whether the lawyers involved in prison litigation will “turn their attention to seclusion in hospital.”Footnote 67 As the following part shows, legal challenges to seclusion in hospitals have already started and, although these cases may prove to be more difficult than those in the prison context, there are several paths to legally contesting seclusion with the objective of better regulating its use.

III. Constitutional and Administrative Challenges to Seclusion

There are three avenues to challenging the use of seclusion in hospitals: (1) test case litigation seeking to declare the practice unconstitutional, (2) class action litigation seeking damages for historic or ongoing misuse of seclusion, and (3) complaints to regulatory colleges for improper use of seclusion. Each avenue comes with benefits and difficulties. The latter two avenues, as this part shows, are already being employed by plaintiff counsel, with some degree of success.

1. Declaring Seclusion Unconstitutional

The most frontal way to restrict the use of seclusion in hospitals is to bring a constitutional challenge seeking to declare the practice unconstitutional in some or all circumstances in which it is presently used. This is also the most challenging avenue.

Most jurisdictions do not have legislation that authorizes, expressly or by implication, the use of seclusion in hospitals. This contrasts with federal and provincial legislation that does authorize the use of isolation in jails, albeit under a new structured intervention unit regime.Footnote 68 This means that there is no obvious law to challenge as being unconstitutional. Legislation in some jurisdictions does explicitly define “restraint” and authorize psychiatric hospitals to restrain NCR patients by using as minimal force as is reasonable to prevent serious bodily harm to the patient or others.Footnote 69 But, even in such circumstances, counsel are likely to be met with an argument that the impugned circumstances were maladministration of the legislation rather than an unconstitutional law. Characterizing systemic constitutional wrongs as isolated incidents of maladministration enables courts to avoid reviewing and remedying the legal and policy schemes that govern ongoing state practices.Footnote 70

The reality is that the legal authorization for seclusion—to the extent that this practice is authorized by law—is found in the common law. The common law is unclear and underdeveloped in this area. The orthodox view is that physicians are authorized and even obligated under the common law to prevent patients from harming themselves or others. The genesis for this authority is a pre-Charter conception of “public necessity” that requires limitations on a patient’s liberty for the benefit of themselves and others.Footnote 71 This reasoning has been extended to justify the legality of psychiatric restraint in the Charter era.Footnote 72

Case law concerning psychiatric restraint, however, “does not set clear or precise limits on the common-law authority to restrain.”Footnote 73 It was also developed before Canadian courts struck down solitary confinement in jails because of the disproportionate harm on offenders, particularly those with serious mental illnesses. As a result, the common law does not adequately take into consideration what we now know about the harms of human isolation, and it does not squarely confront the reality that the psychiatric use of this intervention lacks a robust knowledge basis.

Common-law powers are not immune from legal oversight and revision. In the context of common-law powers that are exercised by police, the Supreme Court of Canada recently remarked that strict limits must be placed on the powers of state actors when individual liberties are engaged.Footnote 74 The onus is always on the state to justify the existence of common-law powers that involve interference with liberty.Footnote 75

The Supreme Court of Canada has also recently remarked that, in a free and democratic society, state actors may interfere with the exercise of individual freedoms only to the extent provided for by law.Footnote 76 State actors must also be aware of the scope of their powers. While they are not expected to be lawyers, they cannot rely on erroneous training and instructions as an excuse for unlawful conduct.Footnote 77

These jurisprudential developments support Wildeman’s claim that “an essential part of the defence of public necessity (and the related defence of protection of third parties) is that the one acting to protect must act reasonably, weigh the proportionality of the response against the risk, and otherwise contain the threatening behaviour in the least restrictive manner possible.”Footnote 78 What once may have been justified can become unjustified when new information is produced on the benefits and harms of a practice. Psychiatrists are already starting to grapple with the ethical dilemma created by an intervention that has no “therapeutic effect” or benefit to the patient but may be needed or perceived to be needed to control their behaviour.Footnote 79 Others now view the use of seclusion as a “treatment failure.”Footnote 80 This is a material change in the circumstances that warrants revisiting how the law governs seclusion.

To displace or refine the existing common-law rules that authorize seclusion, a claimant would have to show that seclusion, in some or all circumstances, is inconsistent with the constitution. The claim would rely on the same right to life, liberty, and security of the person, and the right to be free from cruel and unusual treatment that grounded the solitary confinement challenges. Claimants may also be able to advance discrimination arguments on the grounds that prisoners with mental illnesses receive greater protections against harmful isolation than patients with mental illnesses, but an analysis of such claims is beyond the scope of this article.

Establishing that liberty and protection from cruel and unusual treatment rights are engaged would not be difficult. Current case law recognizes that transfer to a more secure setting in a forensic hospital engages a patient’s liberty interest.82 Moreover, detention for non-punitive reasons is a treatment,Footnote 81 as is the transfer of an inmate to administrative or disciplinary segregation.Footnote 82

Where the claim would face difficulty is in establishing that the risk of harm associated with seclusion is grossly disproportionate or totally out of sync with the objective of patient safety. It would not be enough to prove the harms associated with solitary confinement in prison. Canadian courts are likely to treat jailors and physicians differently, conferring greater deference on the latter because of their expertise. A claimant would have to prove that the solitary-confinement harms are also likely to occur in seclusion under the supervision of medical staff. This is not insurmountable given the existing literature on the objective and subjective harms of seclusion, the authorization of indeterminate isolation in seclusion policies, and the limited attention that those policies place on providing meaningful human contact. However, establishing an equivalence between solitary confinement and seclusion is not the end of what must be established.

The final step would be to convince a judge that these harms are grossly disproportionate or excessive. It is here that physicians may be afforded substantial deference in how they implement social isolation of patients. Courts will be alive to assertions of complexity, violence, and risk in the context of forensic hospitals. Those dynamics are objectively present in forensic hospitals. Additionally, risk assessment is shaped by social stigma: “People with a mental illness are not generally viewed as benign or in need of social support, but are more often considered a public risk.”Footnote 83

Even conceding this risk, at the justification or proportionality phase, the extensive literature on the objective and subjective harms associated with seclusion would have to be confronted. The state would have the onus of proving that the harms are not grossly disproportionate or excessive in the circumstances. This analysis would be informed by recent research showing that seclusion can be significantly reduced without increasing rates of violence in forensic hospitals and in some cases reducing patient-to-staff assaults.Footnote 84 Reductions in the use of seclusion have also been shown to improve patient outcomes, staffing costs (sick time, turnover, and workers’ compensation), and economic expenditures.Footnote 85 The focus would be on the viability of alternative interventions to seclusion that are not harmful or less harmful.Footnote 86

The advantage of this approach is that it addresses the systemic constitutional wrongs associated with secluding patients with serious mental illnesses. It centres the harms, experiences, and human dignity of those people. It invites more widespread declaratory remedies that can reach beyond individual plaintiffs and compel responsive state action, including with the expenditure of funds to alter the forensic care environment. It also makes possible attenuated remedies that outlaw seclusion in some circumstances while permitting it in others.

The disadvantage of this approach is that it is by far the most complex. It faces the inherent difficulty of overcoming accepted practice that is reinforced by social stigma, in circumstances in which there is objective risk to other patients and staff. It is complex and expensive. Expert evidence would be needed. Because the conduct in question falls under provincial responsibility, the Court Challenges Program would not be available to finance the litigation, as it is restricted to federal areas of responsibility.

2. Class or Individual Actions to Recover Damages

A second way to challenge the use of seclusion is to bring a class action or individual actions seeking damages on behalf of forensic patients who have been historically and systemically mistreated in seclusion. Such a claim was recently certified in Tidd v New Brunswick, in which the plaintiffs, all former patients in residential psychiatric care, alleged that common operational failures at the hospital, including the improper use of solitary confinement and restraints, caused them and others harm.Footnote 87 In 2020, another class action claim was commenced against Waypoint Centre for Mental Health Care (a forensic hospital whose policies are included in this article) and the province of Ontario. The claim contends that seclusion is akin to solitary confinement, and that Waypoint has been “systemically negligent by routinely subjecting involuntary patients to solitary confinement […] for weeks, months and sometimes years at a time.”Footnote 88

The goal of this type of litigation is both restitution for the individual patients and behavioural change on the part of the institution. One challenge with this type of litigation is that it is often historic and not forward-looking. For example, a seclusion policy may have changed since the time period of the litigation. Accordingly, a finding of wrongdoing would not necessarily impact the ongoing practice of seclusion.

One feature, however, of class action and ordinary litigation is that it can be quite expensive to defend and can result in substantial damage awards in the millions of dollars.Footnote 89 Indeed, one of the lessons from the solitary confinement class actions is that, when the law shifts, institutions that have been systematically negligent can find themselves exposed to significant damage awards. Leaving aside human dignity arguments, the prospect of damage awards may convince some hospital administrators to take a more proactive and restrictive approach to the use of seclusion. The possibility of large damage awards also makes access-to-justice barriers less pronounced.

3. Complaints to Medical Professional Regulators

The final avenue for challenging seclusion is to bring a professional regulatory complaint against the healthcare professionals who are involved in ordering and implementing seclusion. In Complainant v College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia (No. 1), for example, an inmate in pretrial detention filed a complaint against the psychiatrist who was treating them while they were being held in solitary confinement.Footnote 90 The inquiry panel initially dismissed this complaint on the basis that the prohibition on the use of solitary confinement had not crystallized at the time of the complaint. In overturning this decision, the Health Professions Review Board found that the Mandela Rules informed the ethical obligations of a physician.Footnote 91 The Board then returned the matter to the inquiry panel for it to determine whether and to what extent the Mandela Rules and solitary confinement case law inform the ethical requirements of physicians.Footnote 92

What is significant about this decision and the approach of filing complaints against healthcare professionals is that it will require regulatory bodies to explain why conduct that is profoundly offensive in the penal context should be acceptable in the healthcare context, particularly when medical professionals have been the source of proving the harms associated with isolation in the penal context. If there is evidence showing how the same treatment can be safely used in hospitals—a finding that is not readily apparent from the existing literature—then that evidence will have to be marshalled and presented to regulatory bodies. In other words, the existing professional practice may not be sufficient to protect against a finding of misconduct.

The threat of professional sanction, while again not centrally focused on the human dignity of patients, has the potential to act as a serious deterrent. Administrative complaints processes are easier to access than constitutional claims and class proceedings. Professionals do not like regulatory complaints.Footnote 93 The case reviewed above has been litigated over a four-year period, at significant expense. Even if the physician in that case is successful, the inquiry panel’s dismissal of the complaint rests on the finding that the prohibition of solitary confinement had not been crystallized in or around 2015. This will not protect other healthcare professionals from complaints on a forward basis. At some point, healthcare professionals and their insurers will have to incorporate the human rights consensus on solitary confinement into their practice decisions. This is unlikely to end the use of seclusion, but it may further regulate when and how it is used.

Conclusion

The story of ending solitary confinement in Canada, even if incomplete and ongoing, is one of remarkable judicial recognition that human isolation is profoundly harmful, especially for people with serious mental illnesses. Although the practice of solitary confinement is similar, if not identical, to the practice of seclusion in forensic hospitals, the type of judicial scrutiny imposed on solitary confinement has not been imposed on seclusion.

The differential scrutiny of seclusion is not a product of its harmlessness—far from it. The literature clearly establishes: (1) that seclusion comes with serious risks of objective and subjective harm, and (2) that seclusion does not provide any therapeutic benefit to patients. This has been known since at least the beginning of the twenty-first century. Nonetheless, the practice of seclusion as an administrative tool continues in Canadian forensic hospitals.

One of the main reasons why this practice continues is that there is no legislative framework to regulate seclusion. Instead, a patchwork of provincial and hospital-specific policies govern when and how it is used. These policies are not consistent across the country, do not preclude indeterminate isolation, and do not require meaningful human contact on a daily basis. As a result, the policies do not preclude the possibility that seclusion may be akin to solitary confinement in practice. Indeed, data on the actual use of seclusion suggest that a sizeable percentage of the NCR patient population is exposed to prolonged social isolation every year.

There are three possible legal avenues for challenging this underregulated practice. A constitutional challenge could be brought to modify the common law and restrict when or how seclusion is authorized at common law. This has not occurred to date. What has occurred is the filing of class action lawsuits to address the misuse of seclusion. Patients have also started to file professional regulatory complaints against physicians, arguing that the Mandela Rules should inform medical ethics and professional practice. These latter two avenues have the potential to create litigation, monetary, and professional risk that may deter the ongoing underregulated approach to seclusion.