Introduction

In skilled hands, assisted vaginal birth (AVB) remains the most efficient and effective method of expediting birth in the second stage of labour. It is associated with fewer adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes compared to second stage emergency caesarean section. In this chapter we will focus on the history and role of AVB as it currently stands. We will review relevant literature, examine important areas of practice and suggest a way forward that aims to maintain AVB at the heart of obstetric practice in the twenty-first century. The need for such focus is clear – complications in the second stage of labour (fetal compromise, obstructed labour, maternal exhaustion, or maternal medical conditions exacerbated by the act of pushing) remain a major cause of maternal and neonatal mortality and morbidity across the world. Such complications are responsible for 4 to 13% of maternal deaths in Africa, Asia, Latin America and the Caribbean.Reference Khan, Wojdyla, Say, Gülmezoglu and Look1 In 2013 obstructed labour alone accounted for 0.4 deaths per 100,000 women worldwide.2

Current Practice

Since its introduction to routine clinical practice, AVB has been the preferred approach used by the accoucheur seeking to reduce maternal and neonatal morbidity in the second stage of labour.Reference Arulkumaran, Robson, Arulkumaran and Robson3 In a matched cohort study, compared to assisted vaginal delivery, caesarean section (CS) at full cervical dilatation was associated with higher rates of major haemorrhage >1 L (RR 2.8; 95% CI 1.1 to 7.6) and extended hospital stay ≥6 days (RR 3.5; 95% CI 1.6 to 7.6). Neonatal outcomes with second stage CS showed higher rates of admission for intensive care (RR 2.6; 95% CI 1.2 to 6.0) but lower rates of neonatal trauma (RR 0.4; 95% CI 0.2 to 0.7) compared to forceps.Reference Murphy, Liebling, Verity, Swingler and Patel4

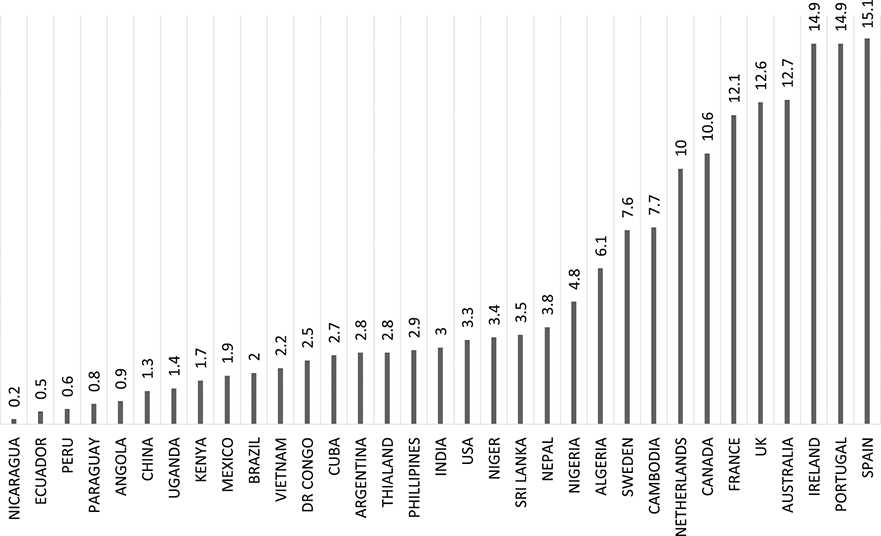

Despite this evidence suggesting an overall benefit for AVB, rates and methods of AVB have remained highly variable over time and between countries. AVB is currently performed with varying frequency in both high- and low-income countries (see Figure 1.1).5–Reference Souza, Gülmezoglu and Lumbiganon8

Figure 1.1 Percentage of births as AVBs in selected countries, 2008 to 2015.

In addition to widespread low levels of utilisation, some surveys found many areas where AVB was not used at all. In 2006 this was the case in 74% (17/23) of Latin American and Caribbean countries, 30% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa and 40% of countries in Asia.Reference Fauveau9

AVB in High-Income Countries

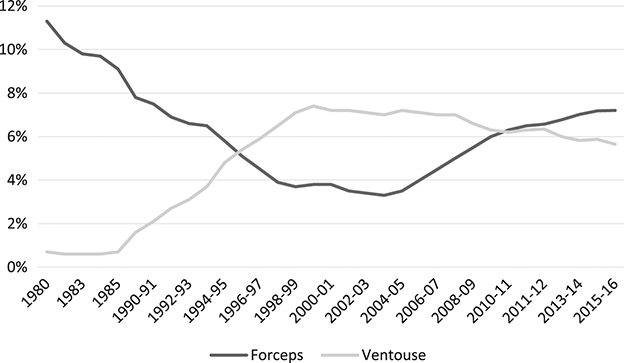

Rates of AVB appear to have remained broadly stable within many high-income countries, although the utilisation of forceps versus ventouse/vacuum delivery has changed over time, with forceps declining and the rate of ventouse/vacuum increasing in many settings. In the UK in 1980, the overall AVB rate was 12%, with 11.3% of all births being performed with forceps but only 0.7% being performed by ventouse/vacuum.10 By 2022 the overall rate of AVB was 11.4%, with 7% of all births performed by forceps and 4.4% performed by ventouse/vacuum.11 This trend is shown in Figure 1.2 (data adapted from NHS Maternity Statistics, annually from 1980 to 2016).

Figure 1.2 Percentage of births performed with forceps and ventouse in the UK, 1980 to 2016.

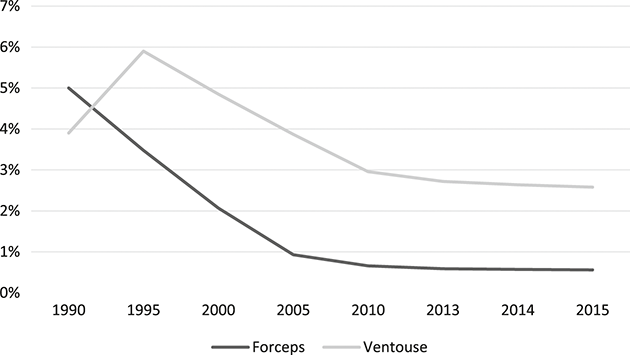

There has been a similar change in Australia, where from 1991 to 2013 the overall AVB rate increased from 12.5% to 18%, with forceps deliveries reducing from 10% of births to 7%, while ventouse/vacuum increased from 2.5% to 11%.5,12 In the USA, AVB rates for both forceps and ventouse/vacuum have consistently declined in the past 30 years, from a level broadly comparable with European countries (9% of all births in 1990) to a current low of 3.12% in 2015, of which forceps were only 0.56% – see Figure 1.3 (data adapted from CDC, National Vital Statistics Reports, 2017).13

Figure 1.3 Percentage of births performed with forceps and ventouse in the USA, 1990 to 2015.

Since 2015, the CDC no longer makes assisted vaginal birth data routinely available, given its infrequent nature within the USA.

Current Instruments for AVB and Associated Outcomes

Non-rotational forceps (Simpson, Rhodes, Neville-Barnes, Anderson, Wrigleys, etc.), manual rotation (usually completed with non-rotational forceps), solid mushroom cup ventouse/vacuum (Malström, Bird and Kiwi) and rotational forceps (Kielland’s forceps) are the obstetric instruments currently in use. Bell cup ventouse/vacuum (silastic/silicone) are used less frequently. Other instruments (e.g. Odon) are still being developed and tested with uncertain applicability. The instruments are associated with different relative benefits and adverse outcomes. These depend not only on specific differences between devices, but also on the different clinical presentations in which the instrument is used (e.g. non-rotational versus rotational births). The different risk/benefit profile for each device, and variable experience in their use, impact on the utilisation rates of individual instruments, as well as the decision whether to attempt AVB or proceed directly to caesarean section.

Non-rotational Instrumental Births

A non-rotational birth is an AVB where the fetal head is not rotated (or rotated <45°) by the accoucheur (either actively – i.e. rotational forceps/manual rotation, or passively – i.e. rotational ventouse/vacuum). Non-rotational births can be performed using non-rotational forceps, solid mushroom cup or bell ventouse/vacuum. Of these, forceps tend to be more successful and associated with less harm to the baby, but are potentially associated with higher maternal morbidity. The most recent Cochrane Review of 10 randomised trials involving 2,923 women showed that the use of forceps was associated with a lower risk of failure as the primary instrument (RR 0.58; CI 0.39 to 0.88) compared to ventouse/vacuum.Reference Verma, Spalding and Wilkinson14 While this is an important finding given the significantly higher rates of maternal and neonatal adverse outcomes associated with the use of sequential instruments, other significant differences need to be considered; thus relative to ventouse/vacuum, forceps is:

■ Less likely to be associated with a low Apgar score at 5 minutes (<7) (RR 1.71, CI 0.59 to 4.95)

■ More likely to be associated with an umbilical arterial pH < 7.2 (RR 1.33, CI 0.91 to 1.93)

■ More likely to be associated with third/fourth degree anal sphincter injury (RR 1.83, CI 1.32 to 2.55)

■ More likely to be associated with post-partum haemorrhage (>500ml) (RR 1.7, CI 0.59 to 4.95)Reference Verma, Spalding and Wilkinson14

■ Possibly less likely to be associated with higher long-term morbidity as a result of pelvic organ prolapse, although this association has not been shown in recent population-level studies.Reference Barber15,Reference Volløyhaug, Mørkved, Salvesen and Salvesen16

Despite the apparent superiority of forceps in non-rotational birth for most maternal and neonatal outcomes, their use is generally lower worldwide than ventouse/vacuum.Reference Deering17

Rotational Births

A rotational birth is an AVB where the fetal head is rotated by the accoucheur by >45° (either actively – i.e. rotational forceps/manual rotation, or passively – i.e. rotational ventouse/vacuum). Rotational births can be performed using mushroom cup ventouse/vacuum (Bird or Kiwi cup), manual rotation followed by direct forceps (or ventouse/vacuum) or rotational forceps.

Rotational births have long been perceived as being proportionately more risky than non-rotational AVBs.Reference Patel18 Reflecting this, the most recent RCOG guideline specifies that rotational deliveries should be conducted in the presence of an experienced operator and in a setting with immediate recourse to caesarean section.Reference Murphy, Strachan and Bahl19 Although some small studies in previous decades have shown poorer neonatal outcomes following attempted rotational forceps births (relative to caesarean section),Reference Chiswick and James20 more recent, larger studies suggest that attempted rotational birth (using any of the three approaches) is not inherently more risky than the alternative of second stage caesarean section,Reference Aiken, Aiken, Alberry, Brockelsby and Scott21 and generates comparable outcomes to non-rotational AVB.Reference Bahl, Macleod, Strachan and Murphy22,Reference Tempest, Hart, Walkinshaw and Hapangama23 This has generated a renewed interest in rotational AVB for the management of malposition of the fetal head at full cervical dilatation.Reference O’Brien, Day and Lenguerrand24–Reference Wattar, Wattar, Gallos and Pirie26

Debate continues about the most effective instrument for rotation and delivery of the fetal head. Whilst the relative efficacy of all three approaches has only been compared in one retrospective cohort study,Reference Bahl, Macleod, Strachan and Murphy22 other studies have examined outcomes of various combinations of two of the three approaches.Reference Tempest, Hart, Walkinshaw and Hapangama23–Reference Al-Suhel, Gill, Robson and Shadbolt25

A large prospective randomised trial is under way in the UK (ROTATE) to examine the outcome of different rotational methods (manual, rotational forceps, rotational ventouse).

Rotational Forceps versus Rotational Ventouse/Vacuum

In single centre trials, rotational forceps appear to be more effective compared to rotational ventouse/vacuum in terms of successful vaginal delivery. A meta-analysis in 2015 analysed eight studies (seven retrospective cohort studies and one prospective cohort study, total 2,399 patients) and reported a statistically significant reduction in the risk of failure to deliver with the intended instrument using rotational forceps compared to rotational ventouse/vacuum (RR 0.32; 95% CI 0.14 to 0.76; p = 0.009), with no significant differences found in any adverse maternal or neonatal outcomes.Reference Wattar, Wattar, Gallos and Pirie26 However, a national audit in the UK showed the same success rate with either rotational forceps or rotational ventouse/vacuum (79%, REDEFINE, unpublished data).

Rotational Forceps versus Manual Rotation Followed by Direct Forceps

Two UK-based retrospective cohort studies have directly compared rotational forceps with manual rotation followed by direct forceps, but they reached different conclusions: Bahl et al. found no differences in any maternal or neonatal outcomes,Reference Bahl, Macleod, Strachan and Murphy22 whilst the study published by O’Brien et al. found a significantly higher chance of vaginal birth using rotational forceps than with manual rotation followed by direct forceps (RR 1.17; CI 1.04 to 1.31, p = 0.017). Additionally, birth by rotational forceps was associated with a significantly higher rate of shoulder dystocia (RR 2.35; CI 1.23 to 4.47, p = 0.012), but with no other differences in maternal or neonatal injuries.Reference O’Brien, Day and Lenguerrand24 Both of these studies were limited by their design (retrospective cohort) and the setting (both studies were restricted to one unit in the same city (Bristol, UK)). Moreover, the number of accoucheurs performing the rotational forceps births in each study was low (three accoucheurs in O’Brien et al.)Reference O’Brien, Day and Lenguerrand24 and this may limit the generalisability of the study findings.

Manual Rotation Followed by Direct Forceps versus Rotational Ventouse/Vacuum

In 2013, in a retrospective study of 263 women, Bahl et al. compared success rates of manual rotation (followed by direct forceps) with rotational ventouse/vacuum and found no significant differences in any outcomes.Reference Bahl, Macleod, Strachan and Murphy22

Despite renewed interest, the performance of rotational AVB remains relatively specialised.

The Way Forward for AVB

In skilled hands and in the majority of cases, AVB remains the safest and most effective means of expediting delivery in the second stage of labour. Multiple pressures, including availability of training, women’s perceptions and concerns surrounding long-term complications, have acted as negative drivers on rates of AVB in many settings, across many countries. Multiple efforts by national and international bodies have not succeeded in preventing the continued rise in caesarean sections in the second stage of labour, and substantial changes to training schedules for junior obstetricians appear unlikely.

Outwith new technologies and large trials, there are approaches which can be used to promote competent and confident use of AVB. For AVB to be used regularly, both individual practitioners and healthcare units need to be confident that the techniques are being deployed safely and effectively. Women and their families need to be active participants in the decision-making, ideally through ample provision of antenatal information, well in advance of labour, as to the options to deliver a baby with malposition. Regular positive feedback, when appropriate, can be a driver that helps to both develop and maintain skills. Real time reporting and collation of outcomes can be useful. This approach, using statistical control charts of simple ‘success’ or ‘failure’ outcomes for attempted ventouse/vacuum deliveries, has been demonstrated to be a useful tool with which to target training within a large teaching unit in the UK.Reference Lane, Weeks and Scholefield27 Reporting and active review of real time outcomes has been practised routinely in surgical specialties in the UK since 2013,28 and large population-based studies have found that this did not lead to a change in surgical patient selection or ‘gaming’ of the system.Reference Vallance, Fearnhead and Kuryba29

In a similar way, it may be useful to encourage real time open reporting of selected outcomes following attempted AVB. Trainees would benefit from confirmation of developing or continued competence, allowing them to grow in confidence and become more assured of their skills. Trainers and hosting hospitals would be able to use the data generated to pick up early when individuals are not meeting expected thresholds of competence. This would allow for focused, targeted training, and correction of ‘less than ideal’ practices at an early stage.

Feedback from women and their families is also necessary and will increase both the perceived and the actual safety of AVB.

AVB has long been considered to be the essential core skill that every obstetrician should be able to confidently offer. Developing and maintaining relevant skills in AVB should continue, supported by an ongoing research base and continuous audit of practice. This will ensure safe, effective and appropriate use of all available AVB techniques.