Introduction

Recruiting appropriate study subjects is critical for conducting sound research to improve health and medical care. Yet, enrolling volunteers into health research remains a significant challenge, as many teams do not have access to systems that facilitate efficient and effective recruitment from specific healthy and patient populations. Typically, health research opportunities tend to be broadly dispersed through a variety of channels. This creates a difficult and inefficient environment for patients and community members to proactively find studies in which they can be involved. To overcome this barrier, the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research, a translational science institute funded by the National Institutes of Health, at the University of Michigan developed UMHealthResearch.org (formerly UMClinicalStudies.org), a web application that links the community to a single gateway for health research opportunities [Reference Dwyer-White, Doshi, Hill and Pienta1].

Before 2013, UMHealthResearch was only designed to be a registry in which volunteers could sign up to receive potential study matches at a later date. This signified a passive approach to volunteering for health research, in which someone would register and wait to be contacted by research teams. We hypothesized that shifting from passive to active engagement would result in higher registration. In this report, we detail our model and process to update UMHealthResearch to provide potential volunteers with a more active way to signify interest and get involved in specific health research opportunities that fit their interests.

Providing opportunities for active research volunteering is important for potential volunteers, as people’s motivation to participate in research is often fleeting. For potential research volunteers, their goal is to sign up for specific research studies being conducted that fit their needs and interests. However, the former registry version of UMHealthResearch did not provide a timely or straightforward method for volunteers to actively show interest in specific research. Thus, it did not capitalize on their switch from deliberating about participation to implementing their goal of participating.

In many ways, making decisions about participating in research is similar to the process of shopping for a product or service. For example, volunteers seek to sign up for specific studies that seem most suited to their needs, just as shoppers seek to purchase a product or service that fits their needs. Thus, models of consumer behavior, such as the buying funnel, are highly relevant and easily adapted to help us consider potential volunteers’ thoughts and behaviors when recruiting for research studies.

The Buying Funnel

The buying funnel (also known as a shopper’s funnel, sales funnel, or sales cycle) is a staged process that a consumer goes through in order to purchase a product or service [Reference Ramos and Cota2]. This model posits that consumers pass through four stages of cognition and action as they decide whether and what product or service to purchase [Reference Jansen and Schuster3]. Specifically, consumers (1) become aware of products or services, (2) research their options, (3) make a decision, and (4) purchase one of the options.

In his work consulting with businesses through Google Ventures, Michael Margolis has adapted the buying funnel to be a user experience design tool for online stores [4]. He proposes 6 general stages in this funnel for Web site design to enhance the user experience when purchasing a service or product:

-

1. Discover: gather options and establish criteria—in this stage, customers try to determine what products are available, what their requirements and criteria are for the product they seek, and which sites are credible sources for information about the product. Therefore, in this stage, Web sites must establish trust with their users and provide clear descriptions of products and their features.

-

2. Select: make a short list—in this stage, customers choose a set of product options that meet their initial screening criteria. Therefore, in this stage, Web sites must provide users with just enough information about a product and allow them to easily shortlist products they like for further examination.

-

3. Dig in: drill into each product—in this stage, once customers consider a product worthy of consideration, they drill into the details to determine whether the product meets their criteria. Therefore, Web sites must provide customers with useful product-specific content that describes a product in detail.

-

4. Validate: find out what people are saying—in this stage, when customers are close to a purchase decision, they look for outside validation from other customers. Therefore, Web sites can provide ratings, reviews and other such validation features to help customers during this stage.

-

5. Try: see what it is really like—in this stage, customers often want to try a product before they commit to help ensure it fits their habits, lifestyle, or the way they work. Therefore, Web sites should make it easy for customers to try products before purchasing or to return products once purchased.

-

6. Buy: in this stage, customers finally purchase the product they were evaluating. Web sites must make it easy and efficient for customers to make the purchase.

Variations of this funnel-like model have been evaluated with and applied to various paradigms including tourism [Reference Sirakaya and Woodside5], online keyword advertising [Reference Jansen and Schuster3], information-seeking [Reference Rose6], and cosmetics [Reference Yang and Lee7]. We posited that it can also be readily and comprehensively applied to health research recruitment, and the model has high potential for designing online research recruitment tools—such as UMHealthResearch—that could be used by multiple research study teams.

Methods

To adapt Margolis’ version of the buying funnel for our needs, we first gathered user feedback on the previous version of UMHealthResearch. We then created the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel based on Margolis’ buying funnel and our user feedback. Finally, we updated UMHealthResearch using our new model as a design tool to create a more active health research volunteer experience.

User Feedback and Creation of the Health Research Participation Funnel

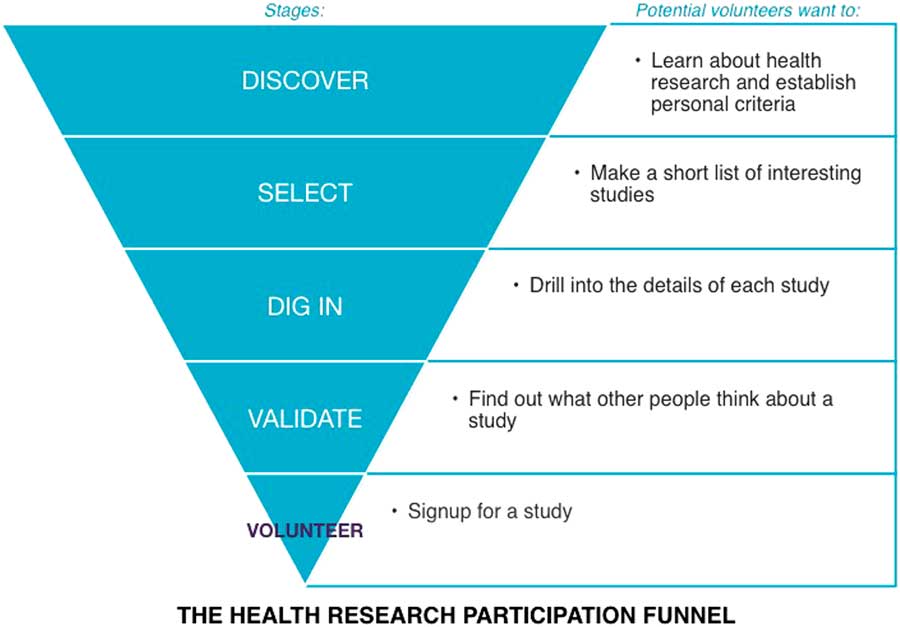

First, we conducted a user research study where we sought feedback from our volunteers through various channels, including in-person interviews, surveys, on-site feedback, and ethnographic studies. We also mined our customer service data to assess the kinds of questions our volunteers were asking. We then synthesized this feedback into broader questions. As a design team, we wanted to be sure to answer these broad questions that users had while searching for a study in which to participate. Thus, we mapped those broad questions to the stages of the buying funnel to create our new Digital Health Research Participation Funnel (see Fig. 1). The Digital Health Research Participation Funnel allowed us to determine how and where to address user needs and concerns. The broad questions that potential volunteers had when interacting with the previous version of UMHealthResearch can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 1 Stages of the Health Research Participation Funnel mapped to what potential volunteers want from each stage.

Table 1 Stages of the Health Research Participation Funnel, what volunteers want in each stage, what recruitment websites must do to address these wants, and improvements made to UMHealthResearch based on these insights

In addition to making the new model more specific to health research participation, 2 other major differences emerged between the new Digital Health Research Participation Funnel and Margolis’ buying funnel. Specifically, we removed the “Try” stage, as this was not applicable to participating in health research through a digital tool. In addition, we replaced the “Buying” stage with “Showing Interest in a Study.” Thus, the final Digital Health Research Participation Funnel consists of 5 stages. In the “Discover” stage, potential volunteers want to learn broad contextual and procedural information about health research and they must establish their own personal criteria for the types of research they are willing to participate in. In the “Select” stage, volunteers narrow down the studies they are interested in so they have a short list of options. In the “Dig In” stage, volunteers drill into the specific details of each study of interest to ensure it meets their personal criteria. In the “Validate” stage, potential volunteers want to know what others who have participated thought about the study. Finally, as mentioned above, volunteers actively show interest in a study that they want to participate in and want to know what the next steps are.

Design Insights Based on the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel

Creating the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel helped us understand potential volunteers’ journeys and thoughts while looking for research studies. In turn, this led to design insights for research recruitment Web sites that mapped onto the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel (see Table 1). Specifically, it is critical for recruitment Web sites to provide sufficient education about research participation, gain user trust, and provide volunteers with an easy way to search for studies when they are in the “Discover” stage. As volunteers move to the “Select” stage, they must be able to easily see relevant information for studies that fit their initial criteria to help them narrow down their options. When volunteers want to “Dig In” to study details, the Web site must quickly show them all the information they need to know in an organized fashion. For volunteers who want to learn what others think of the study, Web sites can create a method for social validation. Finally, when people are ready to volunteer, it should be quick and easy for them to show interest in the study they like and they should have a clear picture of what they need to do next. It is also ideal for the recruitment tool to connect the volunteer with other potential studies of interest to capitalize on their involvement and motivation. After determining these web design insights based on the user feedback and new model, we were able to use these insights to identify problems we needed to address to improve UMHealthResearch and create a more positive and active user experience.

Improvements Made to UMHealthResearch based on the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel

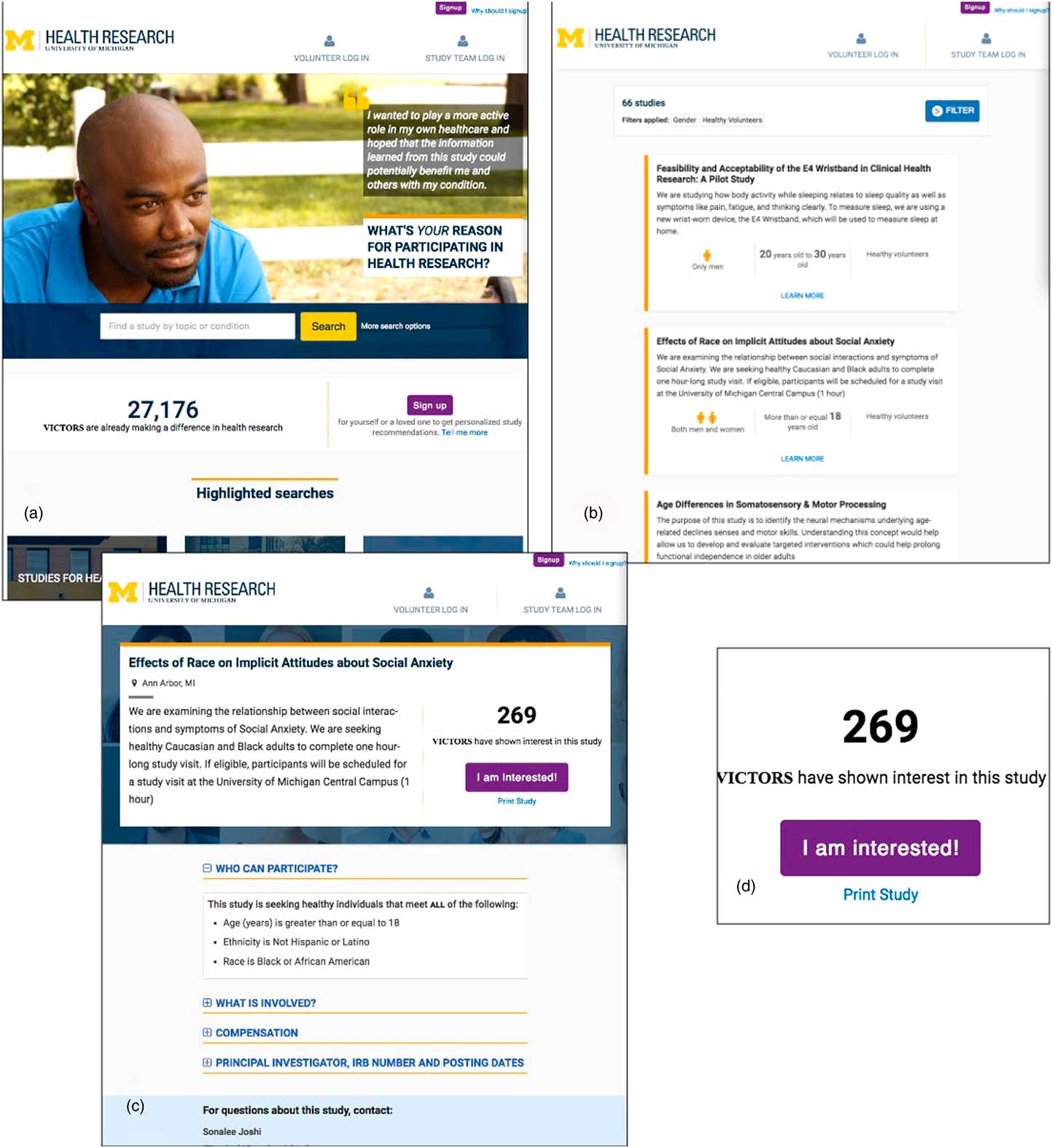

We addressed each insight garnered from the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel through one or more improvements to the previous version of UMHealthResearch (see Table 1). To help volunteers in the “Discover” stage, we ensured that the home page provided sufficient education on Digital health research through multiple modalities. For those in the “Select” stage, we created an easy-to-use search function with easy-to-read and detailed search results. To help people “Dig In,” we ensured that the study detail page answered as many questions as possible; thus, potential volunteers would be fully informed when making participation decisions. For those who seek social validation, we display the number of people who have already shown interest in a particular study. Finally, for those who were ready to volunteer, we created an easy-to-use action button, where volunteers click “I am interested!” to sign up for a study. Examples of these improvements are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2 Screenshots from UMHealthResearch: (a) home page corresponding to the “Discover” stage; (b) study results list corresponding to the “Select” stage; (c) a page showing the details of a specific study corresponding to the “Dig In” stage; and (d) the number of people already interested in a study corresponding to the “Validate” stage and the “I am interested!” button corresponding to the “Volunteer” stage.

Results

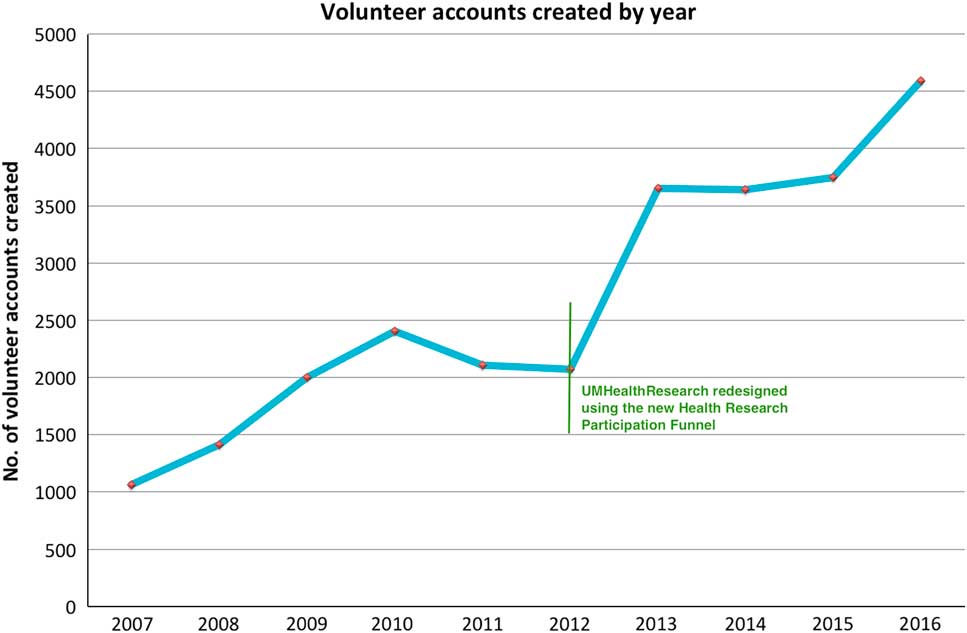

To determine how our improvements to UMHealthResearch based on the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel influenced the performance of the recruitment tool, we examined the number of volunteer accounts created before and after our redesign. As can be seen from Fig. 3, there has been a notable increase in the number of accounts created after our redesign. In the years before the redesign (2007–2012), an average of 1844 new accounts were created every year. In the completed years after the redesign (2013–2016) the average improved to 3906 accounts and more than doubled with an increase of 111%. Since the redesign, volunteers in UMHealthResearch have shown interest in a research study over 120,000 times.

Fig. 3 Volunteer accounts created by year from the beginning of UMHealthResearch’s inception. This includes the timeframe before the buying funnel redesign was implemented and after.

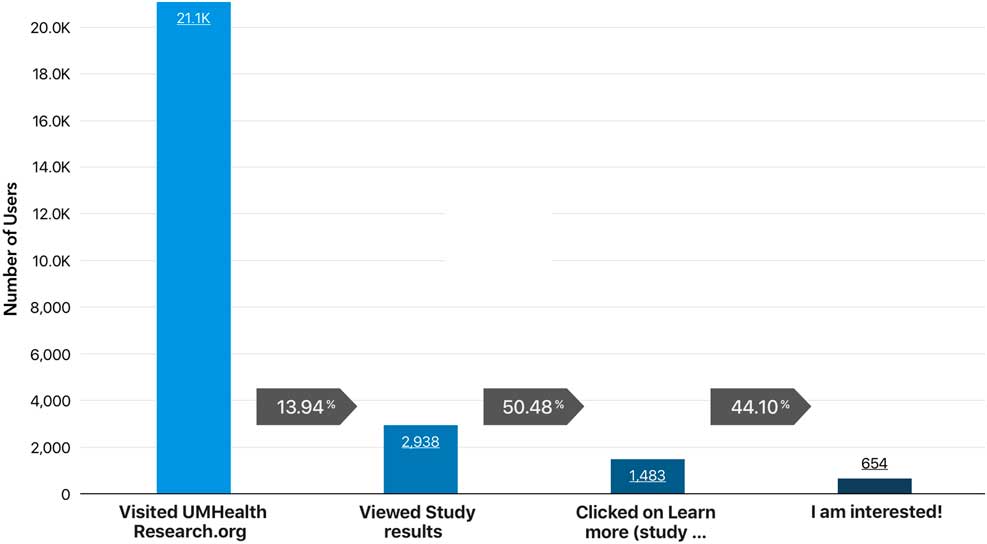

Beginning in October 2016, we started tracking conversion rates at each stage more closely using an event tracking and analytics platform (Heap analytics). In the date range between October 2016 and January 2017, 14% performed a search for research studies or browsed studies by popular topics out of all the people that visited UMHealthResearch, including researchers (to access their administrative portals) and volunteers. Out of this population, about 50% of users looked at a study in detail in the same session. Of those users, about 44% ended up showing interest in a study in that session (Fig. 4). These conversion rates allow us to measure success at each stage of the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel.

Fig. 4 UMHealthResearch user action data through different stages in the time period between October 1, 2016 and January 27, 2017. Roughly translated, these numbers act as the metrics to measure success at each stage of the buying funnel model as applied to UMHealthResearch.

Conclusion

In the previous version of UMHealthResearch, the focus was on volunteers registering, at which point they had to wait for a potential future match—a passive method. After 2013, we focused our design on enabling volunteers to sign up actively for studies. Creating the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel based on consumer engagement principles enabled us to redesign our recruitment tool to allow for a more active user experience. The results of preassessment and postassessment suggest that the focus on user experience improved the performance of UMHealthResearch. As UMHealthResearch grows to support more volunteers, we plan to continue evolving the recruitment tool to fit their needs based on more user feedback, quantitative data, and the Digital Health Research Participation Funnel. Specifically, we continue to focus on increasing conversion rates for each of our stages, or “plugging the leaks in the funnel.” Some new initiatives that are currently being considered include: (1) helping researchers craft postings in a lay-friendly language that is understandable by our volunteers; and (2) encouraging researchers to post more studies in the system to provide volunteers with more choices.

It must be acknowledged that we did not employ a randomized design, and thus we cannot assert unequivocally that the redesign is the causal influence that doubled registration rates. Preassessments and postassessments are subject to the confounds of other changes occurring that might be influential. However, it should be noted that there were no other major initiatives related to recruitment or UMHealthResearch.org at this time. Further, the dramatic and sustained increase after the redesign supports the hypothesis that the shift to active user engagement leads to increased performance. This strategy is likely generalizable and warrants further application in web-based platforms that support recruitment to health-related research.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Meagan Ramsey, Grant Writing Specialist, Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research, for invaluable feedback.

Financial Support

Research reported in this article was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) of the National Institutes of Health under award number UL1TR000433 and UL1TR002240. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.