Introduction and previous research

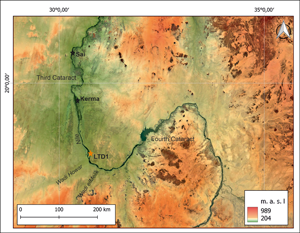

Kerma was the capital of an African kingdom in the Selim Basin, an area of the Third Cataract of the Nile. It evolved from Neolithic pastoral communities in the mid-third millennium BC into an urbanised civilisation capable of creating monumental buildings and necropolises. Its sovereignty came to an end with the Egyptian conquest of Thutmose I in 1504 BC (Anderson Reference Anderson2012). Extensive research on Kerma has been taking place for decades (e.g. Reisner Reference Reisner1923; Bonnet Reference Bonnet1986; Gratien Reference Gratien1978; Bonnet Reference Bonnet2014), but in the past it focused on only two regions: the central area around the Third Cataract; and the remote borderlands of the Fourth Cataract, where only loosely connected funerary sites of the Classic Kerma sub-phase had been recorded (Welsby Reference Welsby2003; Osypiński Reference Osypiński2010). The question of the southern borderlands of the state, whose influence and impact reached such distant areas (Figure 1), remained in the realm of hypothesis and heated debates by scholars. The state of archaeological research showed an astonishing ‘settlement hiatus’ covering a vast area of the Nile Valley between the Third and Fourth Cataracts.

Figure 1. Middle part of the Nile Valley and location of site LTD1. Satellite imagery and DEM: Google Maps/SRTM (www.opentopography.org) (figure by the authors).

New data

In 2021, we began research as part of the ‘Unearthing pan-African crossroads’ project (Osypiński et al. Reference Osypiński, Osypińska, Chłodnicki, Kokolus, Cendrowska, Łopaciuk, Piotrowska, Sobko and Madani2022). One of the key objectives was to assess settlement at the end of prehistory in the middle Nile area—that is, preceding the era of the ancient Kush. The work meant that we not only verified the data on prehistoric settlement in Letti but also discovered new sites on the edge of the desert. In the past, they were located in close proximity to the seasonally overflowing Nile, which formed a wide cultivation zone in the so-called Letti Basin (similar to the location of Kerma itself). Among dozens of new sites, we located extensive settlements from the era of the Kerma kingdom. Along with ceramics characteristic of Kerman manufacture, we discovered other typical settlement artefacts: animal bones and stone artefacts. At one of the sites (designated Letti Desert 1: LTD1), we initiated excavations supported by isotopic analyses of organic artefacts and radiocarbon dating.

The first results revealed that the settlement period at the site lasted continuously for nearly 700 years (Figure 2). The oldest radiocarbon dates from the explored storage pits corresponded to the beginning of the Kerma state—3715 ± 35 bp (Poz-154235) = 2205–2020 cal BC (92.8%)—while the newest corresponded to the period immediately preceding the Egyptian conquest—3275 ± 30 bp (Poz-153193) = 1618–1497 cal BC (91.6%).

Figure 2. Chronology of settlement at LTD1 indicated by radiocarbon dating (figure by the authors).

We established that a monumental mudbrick building was erected at the beginning of the second millennium BC and we uncovered a corner of it in the final days of the 2023 excavation. The thickness of the surviving wall is approximately 1m. Adjacent to it were structures containing large storage vessels and with foundations made of boulders dug into the ground (Figure 3). A few months before our arrival, local farmers had removed the largest boulder of 3m in diameter from this zone because they felt it was a dangerous feature of the landscape. Slightly further away was the ‘granary zone’ where square stone pavements surrounded by postholes remain (Figure 4). In another area of the settlement, we discovered the remains of a metallurgical workshop—fragments of a clay melting pot and small bronze smelts. All these elements point to the high status of the settlement, most likely as a regional settlement centre.

Figure 3. Architectural elements recorded in the eastern part of the LTD1 settlement, marked in red. The size of opened excavation is 5×5m (figure by the authors).

Figure 4. Stone pavements in the western part of the LTD1 settlement, view from the north (figure by the authors).

The first archaeozoological and isotopic analyses also revealed intriguing data. We identified a trend analogous to that observed in the kingdom's capital of a progressive decline in the economic importance of cattle in favour of sheep over centuries (Chaix Reference Chaix, Kroeper, Chłodnicki and Kobusiewicz2007). As civilisation developed while Nubia's desertification continued, cattle was losing economic importance although it remained an extremely important element of the ideological sphere. Cattle was used in funerary rituals, the most numerous deposits of bucrania (frontal bones with magnificent horns) were found around the monumental burials of Kerma's rulers from the late phases of the kingdom's operation (Chaix Reference Chaix, Jousse and Lesur2011). The results of our current analyses indicate that a large proportion of the Letti cattle came from outside the Nile Valley. This discovery was enabled by the extensive strontium isotopic database that we have at our disposal—thanks to the programme of analyses of Pleistocene and Holocene materials. The present state of research means it is not yet possible to define precisely the area of origin of non-local Letti cattle. It is certain that areas to the north (including the area of Kerma) can be excluded. However, later written sources (related to the fourth century BC raids of Meroitic rulers) suggest the opposite direction. Some records claim a southerly direction of herd acquisition from North Kordofan (Osypińska et al. Reference Osypińska, Żurawski, Bełka, Osypiński and Łopaciuk2022), which was connected to this part of the Nile Valley by large, dry channels: Wadi el Melik and Wadi Howar. This would be, in the case of the Kerman material, the first such evidence of far-reaching cattle trade and extensive state relations, extending far beyond the middle Nile.

Conclusions

The Letti data shed new light on the question of the territorial organisation of the kingdom of Kerma and the preference for settlement in zones with a wide strip of floodplain (similar to the capital itself). Further investigations will enable the layout of the settlement to be identified in detail, particularly around the mudbrick buildings and the square stone pavements. Continuing isotope studies will also provide more detailed data on cattle exchange, which is a key element not only economically but also ideologically for all Nubian civilisations.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Bogdan Żurawski who hosted our mission in Banganarti Archaeological Station. We are also grateful to the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums, Khartoum, in addition to the community of Letti for allowing us to study the prehistoric heritage of their land.

Funding statement

Research in Letti was supported by Polish National Science Centre grant UMO-2020/37/B/HS3/00519.