Outside of the subdiscipline of American politics, most political science is qualitative. Predominantly qualitative articles outnumber quantitative and formal articles. Moreover, nearly all political scientists, even those who primarily use other methods, conduct at least some qualitative research. Multi-method research is the new disciplinary norm. In the past two decades, the methods used to conduct this qualitative research have seen much innovation. Scholars such as Bennett and George (Reference Bennett and George2005); Brady and Collier (Reference Brady and Collier2010); King, Keohane, and Verba (Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994); Mahoney and Goertz (Reference Mahoney and Goertz2013); and van Evera (Reference van Evera1997) have revitalized debates over the import, centrality, and rigor of qualitative research. In 2003, the American Political Science Association (APSA) founded a section dedicated to qualitative and multi-methods research; since 2012, APSA has been discussing how to make such scholarship more transparent.

These innovations considerably advanced our understanding of how to improve qualitative research, yet we know very little about how departments have incorporated them into graduate training. In this article, we pose two questions. First, how much training in qualitative methods do political science doctoral programs offer and require today, relative to two decades ago? Second, in departments that offer qualitative methods courses, how much convergence exists on content and pedagogical approach?

To answer these questions, we collected comprehensive data on what was assigned in every methodology course at the 25 top-ranked American political science doctoral programs between 2010 and 2015 (N=261). We evaluated the number and nature of qualitative methods courses compared to those in other methodologies. These measures are comparable to previous studies, which allowed us to estimate trends over time. In addition, we conducted the first detailed content analysis of qualitative and research design courses, evaluating the material treated in syllabi week by week, reading by reading, and assignment by assignment.

Our findings reveal both bad and good news. Our analysis of how much qualitative methods is taught today reveals a disciplinary crisis. Only 60% of the top political science departments offer any focused training in qualitative methods—a decrease during the past 10 to 15 years. For graduate programs to train state-of-the-art, multi-method researchers—as most undoubtedly aspire to do—the majority must enact significant curricular reforms. For departments that seek to make this commitment to excellence, however, our study offers cause for optimism and a clear path forward. In-depth analysis of the content of existing qualitative methods syllabi and curricula reveals substantial convergence on a substantive core of qualitative methods training and effective pedagogical approaches. Based on a customizable list of these items, we recommend three effective ways to incorporate qualitative training into graduate curricula.

METHODS OF CHOICE AMONG TODAY’S POLITICAL SCIENTISTS

Curricular changes in graduate methods training are worthwhile only if they equip emerging scholars with the skills necessary to conduct cutting-edge research. A 2003 study examined the 1,000 most-recent articles in the top 10 political science journals, finding “case-study” analysis present in 46%, “statistical” analysis in 49%, and “formal” analysis in 23% (Bennett, Barth, and Rutherford Reference Bennett, Barth and Rutherford2003, 374). Although 46% comprises a substantial portion of the discipline, measuring methodological use by examining publications in “top” journals severely underestimates the amount of qualitative scholarship in the field.Footnote 1 The list of journals used in such studies oversamples disciplinary journals that focus relatively narrowly on quantitative and formal research while excluding many journals that are primary outlets for research areas dominated by qualitative scholars, such as international security and historical institutionalist studies of American politics (AP).Footnote 2 Moreover, this measure ignores books and book chapters, which generally contain more qualitative research and, indeed, are the most important mode of publication for many qualitative scholars.Footnote 3 Even predominantly quantitative, experimental, and formal researchers often include detailed qualitative analysis solely in book chapters.Footnote 4

Because existing sampling schemes of journals are subject to these biases, a more telling indicator of the importance of qualitative methods may be the number of scholars who primarily use qualitative methods compared to statistical or formal methods. To our knowledge, these data exist only for international relations (IR). In 2012, nearly 60% of IR scholars self-reported conducting predominantly qualitative research, compared to only 15% who conduct mostly quantitative work and less than 1% who conduct primarily formal work (Maliniak, Peterson, and Tierney Reference Maliniak, Peterson and Tierney2012, 34). The dominance of qualitative methods in IR is even more striking when secondary usage is included: more than 85% of empirical IR scholars conduct some qualitative analysis (Maliniak, Peterson, and Tierney Reference Maliniak, Peterson and Tierney2012, 35). Thus, standard journal-based measures underestimate the proportion of qualitative work in IR by at least a factor of two. There is no reason to doubt that a similar bias exists in journal-based estimates of qualitative work in comparative politics (CP) and even in some parts of AP.

In summary, even conservative estimates suggest that qualitative techniques are the most widely used research methods in political science. Given the preponderance of qualitative research across the discipline, how are top departments ensuring that every political scientist masters the techniques needed to do it well?

THE STATE OF THE DISCIPLINE

The first systematic data about graduate methods training appeared in a 2003 PS symposium. Bennett, Barth, and Rutherford (Reference Bennett, Barth and Rutherford2003) juxtaposed these publication trends in top journals with 236 methodology courses offered at 30 of the top-ranked American graduate programs in 1998. All departments in the sample offered a quantitative methods course, whereas only two thirds offered a qualitative methods course. Turning to mandatory courses, two thirds of the departments required quantitative coursework—10 times more than the number requiring qualitative courses (Bennett, Barth, and Rutherford Reference Bennett, Barth and Rutherford2003, 377). To address the disjuncture between courses and the ratio of methods published in journals, the authors recommended that more qualitative courses be offered—and perhaps mandated—in graduate programs.

Schwartz-Shea (Reference Schwartz-Shea2003) reached similar conclusions based on a study of the methods courses in 57 American doctoral programs. She also concluded that the only “methodological core” of the political science discipline is quantitative methods/statistics; agreement on qualitative methods was absent. Every program in the sample offered at least one quantitative course; however, less than half offered even one qualitative course (Schwartz-Shea Reference Schwartz-Shea2003, 382). Furthermore, 66% of programs required a statistics course but only 9% required a course in qualitative methods (Schwartz-Shea Reference Schwartz-Shea2003, 380). She recommended increasing the number of philosophy of science courses as a way to accommodate multiple epistemological approaches.

SAMPLE AND ANALYTICAL APPROACH

Have these calls for change affected curricular decisions in the past 10 to 15 years? To answer this question, this study focuses exclusively on the top 25 American political science doctoral programs as identified by US News and World Report (appendix table A1). To capture course content, we deepened and broadened the measures used in existing research. The 2003 studies evaluated course descriptions and requirements using departmental course lists. However, this approach has the disadvantage (as Schwartz-Shea recognized) of conveying relatively little information about what actually is taught, how in-depth the treatment is, and which techniques are used to teach relevant skills (Schwartz-Shea Reference Schwartz-Shea2003, 380).

Accordingly, we first proceeded as existing studies have: consulting department websites, online course lists, and graduate-student handbooks for each department to generate a preliminary count of courses. We then conducted a second, unprecedentedly intensive form of data collection in which we gathered copies of syllabi (online or by request), simultaneously soliciting information about how frequently each course is offered, typical enrollment rates, and alternative or supplemental training available in other departments or at external institutes. We consulted course instructors, the methodology subfield chair, and/or the director of graduate studies in each program, achieving a response rate of more than 90% on qualitative syllabi. Thus, our data present a nearly comprehensive picture of qualitative methodology training in these departments between 2010 and 2015.Footnote 5 This approach allowed us to measure course content more precisely than previous studies and to describe and analyze the standard pedagogical techniques.Footnote 6

CURRICULAR OFFERINGS AND REQUIREMENTS

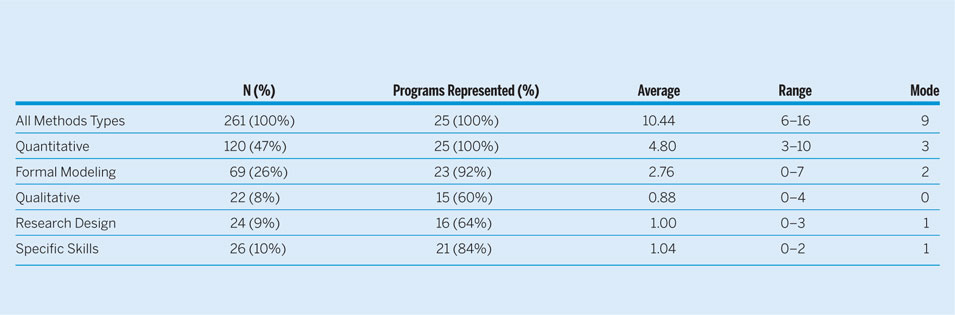

The 25 departments offered 261 unique methods courses. We categorized them into five types according to title and description: quantitative, formal modeling, qualitative, general research design, and specific research skills (table 1).Footnote 7 Quantitative courses include topics such as linear regression and maximum likelihood estimation. Formal modeling courses focus largely on game theory. Qualitative courses cover individual case studies, small-N comparative studies, discourse analysis, and collecting and analyzing qualitative evidence, within a basic ontological and philosophical framework that supports the use of these techniques.Footnote 8 Research design (or “scope and methods”) courses emphasize issues common to any empirical political science work, including measurement, concept formation, philosophy of science, and varieties of social science theory. Courses on specific research skills focus on one technique, such as survey design, experimental design, history, or network analysis.

Table 1 Graduate Methods Courses Offered 2010–2015

Note: The first row provides the average, range, and modal number of courses that constitute a department’s methodology curriculum. The subsequent rows list the average, range, and modal number of each type of methods course offered across departments. See the online appendix for inclusion criteria.

One finding is immediately evident: qualitative methods courses are severely underprovided compared to the proportion of research in the field. Qualitative courses are the least common type of methods course offered, comprising only 8% of the entire sample. They also are offered in surprisingly few departments: whereas all departments offer quantitative training, 40% do not offer any qualitative methods training. In comparison with the findings of Bennett, Barth, and Rutherford (Reference Bennett, Barth and Rutherford2003), these results reveal that the share of total training dedicated to qualitative methods has decreased in the past 15 years in terms of the number of courses (figure 1a) and, even more significant, the number of departments that offer any course (figure 1b).

...qualitative methods courses are severely underprovided compared to the proportion of research in the field.

Figure 1 Methods Courses Offered over Time, (a) Percentage Total Courses, (b) Percentage Total Departments

Note: Data on courses from 1998 as reported in Bennett, Barth, and Rutherford (Reference Bennett, Barth and Rutherford2003). Calculations made by authors.

Whereas course offerings reflect faculty interest, departmental capacity, and/or student demand, course requirements may more accurately portray departmental commitment to training for career success. Twenty-eight courses in our sample are required, representing slightly more than 10% of the total. This distribution reveals a similar pattern of emphasis on statistical and formal rather than qualitative methods (figure 2). Six departments impose quantitative requirements and 10 require general research design, whereas only two require qualitative training. Of these two, one requirement is only for CP students and the other requirement can be met with a general research design course. In summary, although qualitative research is the dominant method in the field, no top program requires all students to be trained in qualitative methods.

Figure 2 Current Course Requirements

Note: N=28. Because the qualitative courses are required for only a subset of students, the courses are represented but not the departments.

THE COMMON CORE OF MODERN QUALITATIVE TRAINING

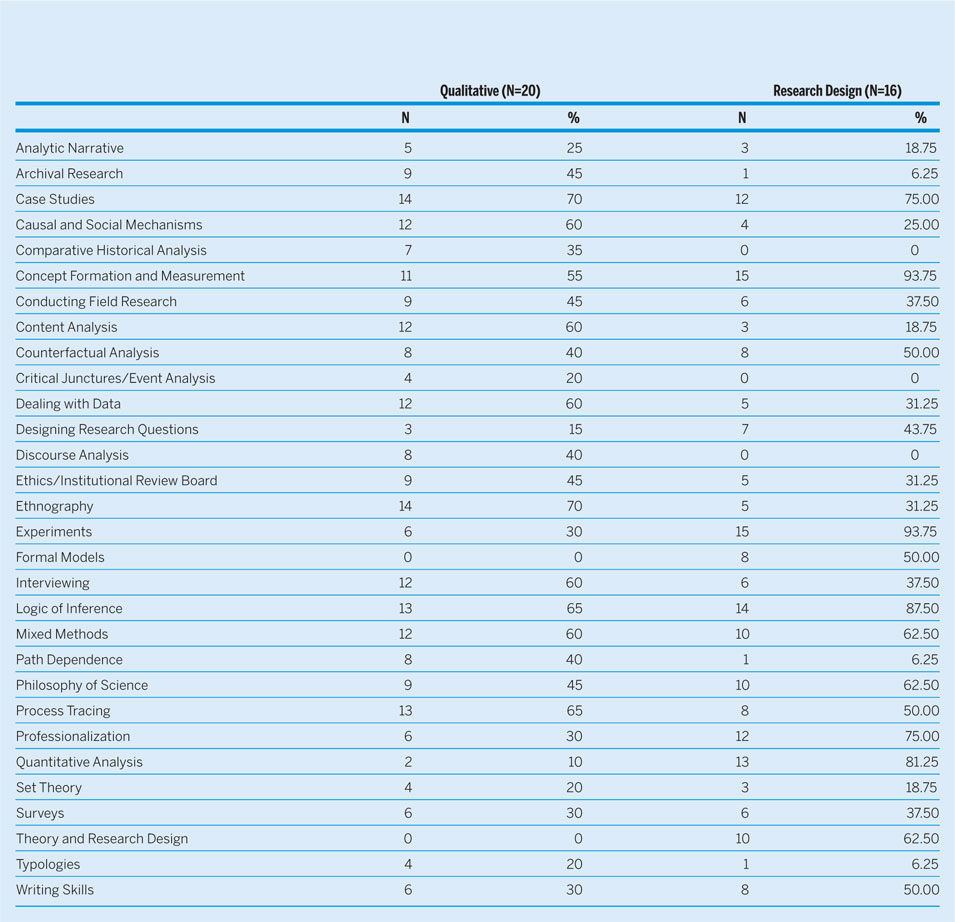

What specific knowledge and research skills do these curricular choices emphasize or neglect? To what extent does a common core of qualitative methods exist? To answer these questions, we analyzed the content of qualitative methods course syllabi by readings and assignments to identify common topics, themes, and pedagogical techniques. Of the 22 qualitative research methods courses taught across 15 departments, 20 syllabi (91%) from 13 schools were available for analysis. Table 2 lists all course topics that appear in at least 20% of the sample. We then created a typology of these topics along two dimensions: type (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or general) and stage of the research process (i.e., design, data collection, data analysis, or presentation).Footnote 9

Table 2 Common Course Components in Qualitative and Research Design Courses

To distill the “typical” content of a qualitative research methods course, we considered the components present in at least half of the sample. This snapshot suggests that such courses balance broad research design issues with training in concrete skills and techniques. On average, slightly less than half of a typical qualitative research methods course comprises distinctively qualitative issues of general research design, and slightly more than half is devoted to concrete skills and techniques of qualitative data collection (“field methods”) and data analysis. Courses typically supplement the latter with “learning-by-doing” activities, such as visiting archives, implementing interview protocols, conducting local ethnographic studies, and replicating preexisting work—the equivalent of problem sets, replication, and small statistical projects in quantitative courses (appendix figure A1). Six courses incorporate an ongoing fieldwork project, most requiring students to spend time “on site” for several hours per week. Thus, we conclude that the discipline has developed a substantial consensus around what constitutes qualitative methods and that teaching such methods contains both conceptual and “hands-on” components.

Among the 40% of departments that do not offer a single qualitative methods course, all but two offer a general research design course. Fifteen of these departments (60%) seem to structure their curriculum so that either qualitative methods or general research design is offered—a distribution consistent with the view that some departments perceive them, consciously or not, as substitutes. If the two courses are substantively comparable, perhaps we underestimated existing qualitative training; therefore, we examined them closely.

To assess whether general research design courses actually can substitute for a dedicated qualitative methods class, we analyzed 16 general research design syllabi representing 13 departments. Comparison of course components in table 2 reveals very little overlap with qualitative methods courses. Insofar as overlap does exist, it is not because research design courses cover qualitative topics but rather because qualitative courses typically include issues of general research design (figure 3). We conclude that most essential qualitative research techniques cannot be acquired in traditional research design courses.

We conclude that most essential qualitative research techniques cannot be acquired in traditional research design courses.

Figure 3 Standard Course Composition by Component Type, (a) Qualitative Courses, (b) Research Design Courses

Note: Calculations are based on component appearance in at least 50% of course syllabi.

(RE-)DESIGNING A QUALITATIVE METHODS CURRICULUM

We have shown that nearly half of political science departments seeking to train graduate students to conduct state-of-the-art, multi-method research are not currently providing training in qualitative methods. Today, this training should take account not only of recent innovations in qualitative methodological scholarship but also of the consensus that all methods should be taught through active learning. To achieve that goal, most of the top graduate programs must significantly reform and enhance their qualitative methods curricula. Based on our evaluation, we propose three alternative curricular approaches that can be used to achieve this goal. In increasing order of ambition, they are the single-course, multi-course, and comprehensive options.

The Single-Course Option

For the 40% of mono-methodological departments that offer graduate students no in-house opportunities to receive training in qualitative methods, a minimal option would be to inaugurate a single dedicated course. Whereas this qualitative methods course may include a few basic topics also covered in general research design courses (e.g., concept formation, measurement, and mixed-method design), approximately two thirds of such a course should focus explicitly on concrete techniques of qualitative design, data collection, and analysis. Essential topics include process tracing and social mechanisms, single-case analysis, small-N case comparison, interviewing, archival research, ethnography, participant observation, and other field methods. Departments that already offer a single course of this type should keep it current by entrusting it to a faculty member familiar with the rapidly evolving qualitative methods literature. From a pedagogical perspective, it also is essential to design this course around active “learning by doing,” which includes designing and critiquing elements of a research design, replicating existing research, and carrying out common field research tasks.

The Multi-Course Option

Regardless of how current and well designed it may be, inherent scope limitations in a single course have led some departments to consider multi-course sequences. We believe this should be recognized as the new minimal standard for top political science departments. The relevant methodological literature is now large and diverse enough that it is becoming impractical for a one-term course to offer an introduction to general research design, introduce fundamental literature on qualitative causal inference, present specific field research and data analysis skills identified previously, and incorporate active-learning exercises. More than one course is required. Emory University’s two-course sequence provides a useful template: the first course focuses on general methodological issues and the second emphasizes concrete applications of specific qualitative research techniques.

The Comprehensive Option

The current “gold standard” of state-of-the-art qualitative methods training consists of a multi-course sequence designed to establish qualitative methods as a comprehensive exam field. Since 2009, Yale University’s department has demonstrated its commitment to professional training in this way. The comprehensive exam field is conventionally designed: a student can take three courses (including at least one significant research paper) or take a written comprehensive exam focused on a reading list of canonical texts. Faculty members strongly advise students to choose the former because it maximizes opportunities for active learning. The three core courses are offered regularly. Students can choose to take all three or to substitute one for a preapproved, substantive course that is particularly attentive to qualitative methods. One core course includes a term-length project that requires application of qualitative research techniques in the student’s local field site. Although this option is demanding—it requires a significant commitment of faculty time and, realistically, interdisciplinary cooperation—departments that want to be at the forefront of qualitative or mixed-methods training should seek to emulate it.Footnote 10

CONCLUSION: THE FUTURE DIRECTION OF QUALITATIVE TRAINING

Exposing graduate students to unbiased state-of-the-art methods training is vital to the future trajectory of political science research. The current state of the discipline is a bad-news/good-news story. The bad news is that despite robust innovation in cutting-edge methods and prior studies demonstrating the disjuncture between research priorities and methods training, the commitment of political science to qualitative methods training has barely evolved in two decades. Our study documented this in detail.

The good news is that those departments that do teach qualitative methods share a substantial consensus about what should be taught and how to teach it. This means that departments committed to multi-method research can change course relatively easily if they allocate the necessary resources. We proposed several options for implementing qualitative research training and suggest that the two-course sequence should be seen as the new minimum. Morrow (Reference Morrow2003) was correct that specialization in particular methods allows for departmental diversity in the field going forward. However, departments that want to be at the cutting edge of training all types of researchers—including those who use the discipline’s most prevalent method—must incorporate more structured qualitative research training in their graduate curricula. The willingness to enact these reforms is a clear litmus test for whether departments actually believe in multi-method political science or simply pay lip service to it. If a more rigorous qualitative and multi-method discipline is the goal, longer-term changes must extend beyond graduate curriculum to include undergraduate curriculum, hiring decisions, conferences, and methods textbooks. A focused conversation on graduate curriculum therefore should be viewed as a necessary first step in a longer evolution toward richer, more rigorous, and more diverse political science.

...those departments that do teach qualitative methods share a substantial consensus about what should be taught and how to teach it.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096519001719.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We extend special thanks to Andrew Bennett for consulting with us on his 2003 study, as well as all of the instructors who made their syllabi available for analysis and participated in the survey. We also thank Colin Elman, Robert Keohane, Tommaso Pavone, Andrew Proctor, Travis Sharp, participants in the Princeton Qualitative Research Colloquium, and discussants at the 2016 SPSA, 2016 APSA, and 2017 MPSA Annual Meetings for useful feedback in the early stages of this project.