I. Introduction 26

II. The Objective versus Subjective Controversy over the Meaning of Investment 26 A.The trend towards an objective meaning in the practice of investment tribunals28 B.Evolving the meaning of investment through interpretation35 C.The inconclusive travaux préparatoires on the definition of investment39

III. The Objective Elements of Investments 42 A.Objective elements of investments in the negotiations of the ICSID Convention43 B.The Salini criteria and their critics46 i.Contribution52 ii.Duration56 iii.Risk56 iv.(Contribution to the) economic development of the host State58 v.Profit and return60 vi.Territoriality60 vii.Investments in accordance with the laws of the host State or good faith investments62 C.The new objectivism: objective in name only63 D.The commercial transaction test: distinguishing investments from commercial transactions67 E.Elements of investments in ICSID Additional Facility, UNCITRAL or SCC cases68

IV. Special and Controversial Cases of Investments 71 A.Financial instruments: lack of legal certainty71 B.Arbitral awards and judgments as investments75 i.Commercial arbitral awards75 ii.Investment arbitral awards77 iii.Judgments of national courts in the host country77

V. Conclusion 78

Appendix: Lists of cases covered in this study 79

I. Introduction

-

1. The subject of this volume of the ICSID Reports is the notion of “investment” – the crucial touchstone of the subject matter jurisdiction of ICSID tribunals. As is well known, the ICSID Convention does not define what “investments” are. Article 25 ICSID Convention, the only provision on the subject matter jurisdiction of ICSID tribunals, merely refers to “investment”. Investment tribunals and the literature have adopted divergent approaches with respect to two specific features of the term “investment”. These two features are: (i) whether “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention has an objective meaning, in addition to the definition of investment in the instrument of consent/the investment treaty (the controversy over the objective versus subjective meaning of investment); and (ii) if “investment” has an objective meaning, which elements ought to be used to objectively determine investments (the controversy about objective or characteristic elements of investments). Specifically, there has been some controversy as to whether an objective element is that the transaction contributes to the host country’s economic development.

-

2. This study explores both features. It focuses on the second feature because the objective elements that may characterise investments have considerable practical relevance for the jurisdictional determinations of ICSID tribunals. Section II analyses whether “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention has an objective meaning, and whether the term “investment” has evolved over time. Section III examines possible objective elements of investments. Section IV considers two special cases whose investment status is unclear considering these two controversies: first, whether financial instruments qualify as investments and, second, whether commercial arbitration awards, investment awards or judgments by national courts in the host country qualify as investments.

II. The objective versus subjective controversy over the meaning of investment

-

3. The controversy over the objective or subjective meaning of investment that is the subject of this Section concerns the implications of the ICSID Convention’s failure to define investment: does it mean that Article 25 ICSID Convention does not limit which transactions count as investments (subjective meaning), leaving this definition entirely to the instrument of consent; or do certain transactions not qualify as investments because they do not exhibit characteristic features of investments (objective meaning)?

-

[Page 27] 4. A first group of tribunals uses the failure of the delegates who negotiated the ICSID Convention to define investment in support of the conclusion that Article 25 ICSID Convention refers to an objective meaning of investment, or at least an objective core of investment. By contrast, a second group of tribunals considers that the absence of a definition means that there is no objective definition of investment. Accordingly, the silence in Article 25 ICSID Convention shifts the exclusive focus to the instrument of consent, to which alone the definition of investment is left: the investment contract, the domestic investment statute or the investment treaty. The definitions of “investments” in investment statutes and treaties strongly resemble each other.Footnote 1

-

5. Views in the literature on the definition of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention divide along similar lines.Footnote 2 A first school of thought holds that the silence in Article 25 ICSID Convention on the definition of investment is a simple silence, an unintended gap, which does not warrant extensive interpretation as a matter of course.Footnote 3 A second school of thought holds that the silence is qualified (or strategic) such that there is no gap – the drafters of the ICSID Convention deliberately left the term undefined and delegated the definition of investment to future decision-makers (the drafters of the instrument of consent and/or investment tribunals) – prompting some tribunals to interpret the term “investment” broadly.Footnote 4 [Page 28] Accordingly, the absence of a definition of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention means that the instrument of consent alone, usually an investment treaty in recent decades, defines what counts as an investment.

A. The trend towards an objective meaning in the practice of investment tribunals

-

6. Investment tribunals have increasingly accepted that the meaning of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention is objective and cannot be varied by the two parties to a bilateral investment treaty.Footnote 5 Even though a few tribunals continue to adhere to the “subjective” meaning of investment,Footnote 6 an increasing line of decisions finds that Article 25 ICSID Convention contains an “objective” meaning of investment,Footnote 7 including 12 of the 25 decisions summarised in this volume.Footnote 8 Accordingly, ICSID tribunals assess whether a transaction falls within Article 25 ICSID Convention’s own notion of “investment”. Some regard Article 25 ICSID Convention as a device to prevent the floodgates to ICSID arbitration from being opened.Footnote 9

-

[Page 29] 7. This approach is also known as the “outer limits” test,Footnote 10 or a “double-barrelled test”.Footnote 11 This is because tribunals assess, over and above the applicable investment treaty, whether the transaction qualifies as an investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention. The first leg (or barrel) is the investment treaty, whereas the second is Article 25 ICSID Convention. Accordingly, an investment treaty can restrict the subject matter scope of the ICSID Convention as regards the requirement of an investment but cannot expand it.Footnote 12

-

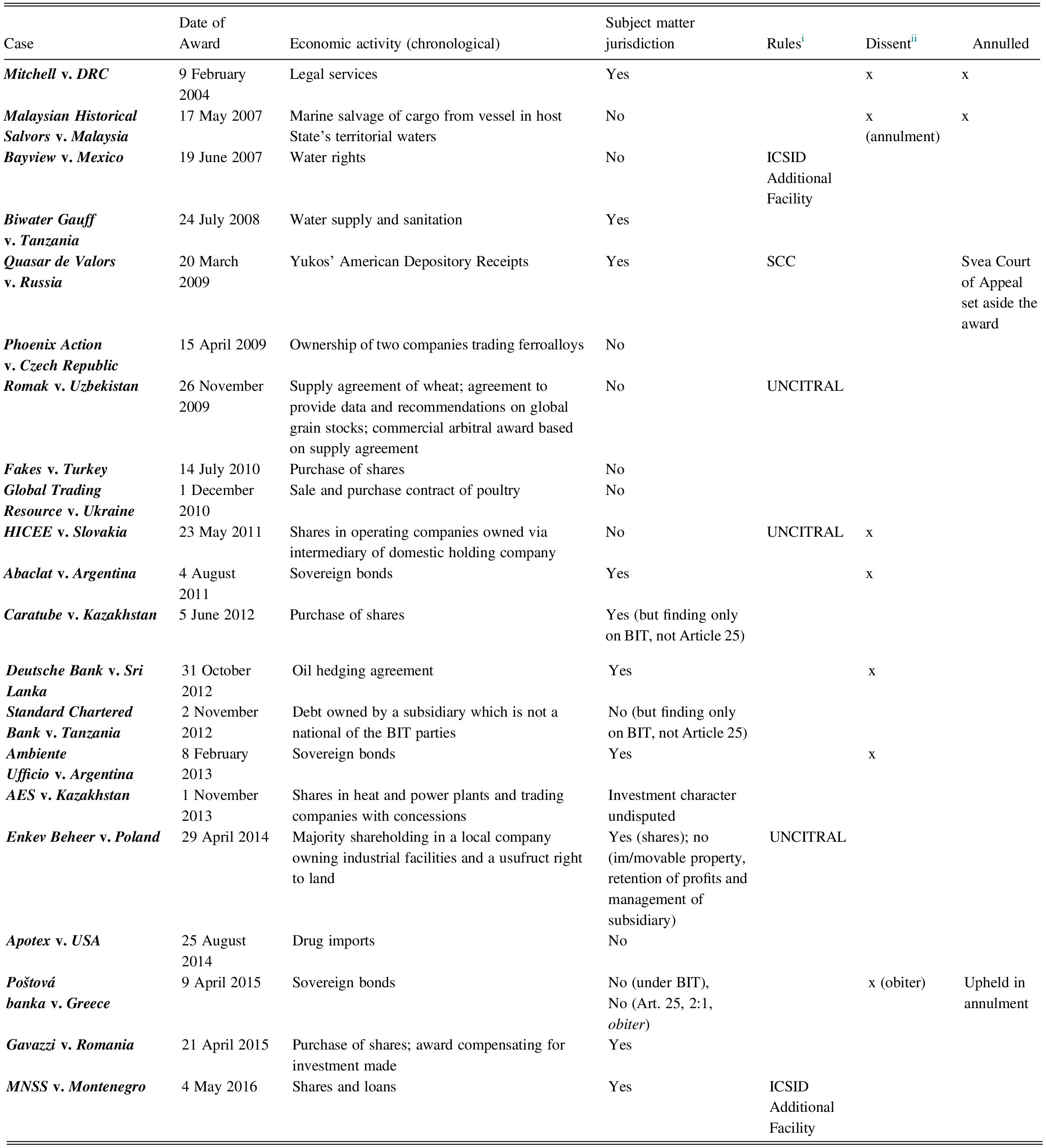

8. Table 1 summarises the cases reported in this volume. For each of the 21 cases (column 1), organised by year of the decision or award in ascending order (column 2), Table 1 shows:

-

a. the economic activity that the investor contended amounted to an investment (column 3);

-

b. whether the tribunal affirmed or declined jurisdiction (column 4);

-

c. the applicable arbitration rules, other than the ICSID Arbitration Rules (column 5);

-

d. whether an arbitrator dissented on jurisdiction (column 6); and

-

e. whether an ad hoc annulment committee annulled the jurisdictional finding of the tribunal (column 7).

Table 1 Decisions of investment tribunals on the notion of investment

-

-

9. A few important awards on the notion of investment do not appear in this volume because they have already appeared in previous volumes of the ICSID Reports.Footnote 13 Examples include Fedax v. Venezuela,Footnote 14 Salini v. Morocco Footnote 15 – the originator of the Salini criteria examined below – and Joy Mining v. Egypt.Footnote 16

-

10. Whether there is a second barrel is significant because many investment treaties (mostly concluded in the 1990s and the 2000s) adopt a broad, asset-backed definition of investment with illustrative examples. This contrasts with the ICSID Convention of 1965. Depending on one’s views, either the ICSID Convention adopted a narrower view of what constitutes investment than the one found in most investment treaties, or the Convention did not adopt any definition at all.Footnote 17 Notably, investment treaties often include in their definition of investment [Page 32] “every kind of asset” and “claims to money”Footnote 18 or “obligations” and “any right of an economic nature granted by law or by contract”.Footnote 19 Remarkably, the definitions of investment in some investment treaties are circular,Footnote 20 or mix forms of investment with rights associated with them.Footnote 21 The qualification of financial instruments as an investment by some tribunals illustrates the breadth of the typical definition found in investment treaties (see paras. 111–20 below).

-

11. Some investment treaties concluded in recent years expressly exclude certain transactions from the notion of investment. A good example is the “investment” definition in Article 8.1 of the EU–Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA):Footnote 22

investment means every kind of asset that an investor owns or controls, directly or indirectly, that has the characteristics of an investment, which includes a certain duration and other characteristics such as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk. Forms that an investment may take include:

-

(a) an enterprise;

-

(b) shares, stocks and other forms of equity participation in an enterprise;

-

(c) bonds, debentures and other debt instruments of an enterprise;

-

(d) a loan to an enterprise;

-

(e) any other kind of interest in an enterprise;

-

(f) an interest arising from:

-

(i) a concession conferred pursuant to the law of a Party or under a contract, including to search for, cultivate, extract or exploit natural resources,

-

(ii) a turnkey, construction, production or revenue-sharing contract; or

-

(iii) other similar contracts;

-

-

[Page 33] (g) intellectual property rights;

-

(h) other moveable property, tangible or intangible, or immovable property and related rights;

-

(i) claims to money or claims to performance under a contract.

-

For greater certainty, claims to money does not include:

-

(a) claims to money that arise solely from commercial contracts for the sale of goods or services by a natural person or enterprise in the territory of a Party to a natural person or enterprise in the territory of the other Party.

-

(b) the domestic financing of such contracts; or

-

(c) any order, judgment, or arbitral award related to sub-subparagraph (a) or (b).

Returns that are invested shall be treated as investments. Any alteration of the form in which assets are invested or reinvested does not affect their qualification as investment;

investor means a Party, a natural person or an enterprise of a Party, other than a branch or a representative office, that seeks to make, is making or has made an investment in the territory of the other Party;

-

-

12. Article 8.1 CETA uses an asset-backed definition of investment (“every kind of asset”), coupled with illustrative examples of investments. However, it also contains some exclusions such as claims to money related to the delivery of goods or services, and associated judgments and awards. The definition also relies on characteristics of investments that Schreuer and the Salini tribunal identified (see below para. 47). In a similar vein, Article 14.1 United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA) refers to “every asset … that has the characteristics of an investment, including such characteristics as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk”.Footnote 23 That article further adds illustrative examples and exclusions such as “commercial contracts for the sale of goods or services”:

investment means every asset that an investor owns or controls, directly or indirectly, that has the characteristics of an investment, including such characteristics as the commitment of capital or other resources, the expectation of gain or profit, or the assumption of risk. An investment may include:

-

(a) an enterprise;

-

(b) shares, stock and other forms of equity participation in an enterprise;

-

(c) bonds, debentures, other debt instruments, and loans;

-

[Footnote fn. 1: Some forms of debt, such as bonds, debentures, and long-term notes or loans, are more likely to have the characteristics of an investment, while other forms of debt, such as claims to payment that are immediately due, are less likely to have these characteristics.]

-

-

(d) futures, options, and other derivatives;

-

(e) turnkey, construction, management, production, concession, revenue-sharing, and other similar contracts;

-

(f) intellectual property rights;

-

[Page 34] (g) licenses, authorizations, permits, and similar rights conferred pursuant to a Party’s law; and

-

[Footnote fn. 2: Whether a particular type of license, authorization, permit, or similar instrument (including a concession to the extent that it has the nature of such an instrument) has the characteristics of an investment depends on such factors as the nature and extent of the rights that the holder has under a Party’s law. For greater certainty, among such instruments that do not have the characteristics of an investment are those that do not create any rights protected under the Party’s law. For greater certainty, the foregoing is without prejudice to whether any asset associated with such instruments has the characteristics of an investment.]

-

-

(h) other tangible or intangible, movable or immovable property, and related property rights, such as liens, mortgages, pledges, and leases,

but investment does not mean:

-

(i) an order or judgment entered in a judicial or administrative action;

-

(j) claims to money that arise solely from:

-

(i) commercial contracts for the sale of goods or services by a natural person or enterprise in the territory of a Party to an enterprise in the territory of another Party, or

-

(ii) the extension of credit in connection with a commercial contract referred to in subparagraph (j)(i);

-

-

-

13. A similar approach can be found in definition of investment under the EU–Vietnam Investment Protection Agreement,Footnote 24 which excludes “claims to money that arise solely from commercial contracts for the sale of goods or services … or any related order, judgement, or arbitral award”.Footnote 25

-

14. By contrast, the India Model BIT excludes a wider range of transactions, including portfolio investment.Footnote 26 For example, Article 2.4.1(iv) of the Brazil–India [Page 35] BIT states that “investment” does not include “portfolio investments of the enterprise or in another enterprise”.Footnote 27 The India–Taiwan BIT also contains a similar definition and categorises portfolio investments as an ownership interest of less than 10 per cent.Footnote 28 Similar to the above treaties, the India Model BIT and India’s treaties concluded thereafter rely on the elements of investments that Schreuer and the Salini tribunal identified or a variant thereof. Provided the purchases of shares amount to foreign direct investment, rather than portfolio investment, such transactions qualify as investments under these investment treaties.Footnote 29

-

15. At bottom, there are two different conceptions of “investment” that tribunals and the literature use. The first conception considers that States have the freedom to customise what counts as an investment in their BITs, without limitation. There is no numerus clausus principle in international investment law – the definition of investment is akin to contract.Footnote 30 The second conception considers that the notion of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention is akin to property. A numerus clausus applies, and hence only interests that conform to a limited number of standard forms are protected.Footnote 31

B. Evolving the meaning of investment through interpretation

-

16. As the next subsection below shows, the drafters of the ICSID Convention left the notion of “investment” ambiguous. And even if the meaning of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention was narrower than the definition of investment in modern investment treaties, it does not necessarily follow that this notion of investment remains the same today as in 1965. The “objective” meaning of investment could assume a broader, more modern meaning through interpretation. The meaning of treaty terms such as “investment” is not necessarily static but could evolve over time.

-

17. While there are no known examples of investment tribunals expressly applying evolutionary interpretation in the specific context of the definition of investment, there is no doubt that the meaning of terms such as “investment” can [Page 36] evolve.Footnote 32 Other international courts and tribunals, including the ICJ, have relied on evolutionary interpretation.Footnote 33 In the Dispute regarding Navigational and Related Rights, the ICJ considered whether the meaning of terms in an 1858 bilateral treaty between Costa Rica and Nicaragua concerning the San Juan River had evolved over the last 150 years.Footnote 34 Considering some subsequent practice of the two disputing States, the ICJ opted for a dynamic interpretation of another economic term, namely “libre navegación … con objetos de comercio”, albeit of a right rather than a jurisdictional title. The ICJ explained:

[the Court’s practice of interpreting clauses in line with their meaning at the time of conclusion] does not however signify that, where a term’s meaning is no longer the same as it was at the date of conclusion, no account should ever be taken of its meaning at the time when the treaty is to be interpreted for purposes of applying it.Footnote 35

-

18. Similarly, the term “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention could be found to have an evolutionary character. With respect to treaties concluded for a long period of time, such as the ICSID Convention, “the parties’ intent upon conclusion of the treaty was, or may be presumed to have been, to give the terms used – or some of them – a meaning or content capable of evolving, not one fixed once and for all, so as to make allowance for, among other things, developments in international law”.Footnote 36

-

19. Even though no investment tribunal thus far has expressly couched its analysis of “investment” in these terms, in some awards – such as Abaclat Footnote 37 – tribunals arguably adopted the view that “investment” has an evolutionary meaning.Footnote 38 Arbitrator Abi-Saab dissented vigorously on this point, referring to the [Page 37] “tenuous and untenable interpretations, particularly of jurisdictional titles, over-stretching the text beyond the breaking point, in order to extend jurisdiction to where it does not exist”.Footnote 39 The Salini tribunal’s finding on the “contribution to economic development of the host State” could also be seen as evolutionary interpretation because the tribunal did not pay regard to what this phrase meant in 1965.Footnote 40 The annulment committee in Mitchell v. DRC acknowledged that some cases “broadened” the meaning of investment compared to the 1965 meaning of investment, but concluded that this did not change the meaning in the instant case.Footnote 41

-

20. The tribunal in HICEE v. Slovakia, a non-ICSID arbitration, adopted an anticipatory, rather than evolutionary, approach to investment treaty interpretation. The dispute concerned shares in two Slovak health insurance companies. The tribunal was open to interpret the investment treaty based not on the conditions at the time of its negotiation but rather the economic transition that the parties anticipated for the future:

The Tribunal only feels it necessary to observe that BITs are, by definition, concluded for the future not just for the present, and that there was nothing to prevent either side – i.e. the Dutch side quite as much as the Czechoslovak side – wanting to provide in advance for a more liberal economic regime that was on its way.Footnote 42

-

21. As a matter of treaty interpretation, the definition of “investment” in an investment treaty can affect the interpretation of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention in three ways. A first possibility is that the investment treaty qualifies as a subsequent agreement or subsequent practice under Article 31(3)(a) or (b) VCLT between two States both of which are parties to the ICSID Convention.Footnote 43 Investment treaties could impact the meaning of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention through subsequent agreement (subparagraph (a) of Article 31(3) VCLT) or subsequent practice (subparagraph (b) of Article 31(3) VCLT). However, the insurmountable hurdle for both is that subsequent agreements and practice need to be common to all parties to the treaty, and that the rules need to be applicable in the relationship between all the parties.Footnote 44 As Pahis notes, “BITs are [Page 38] neither of these. An agreement between two of the State parties to the ICSID Convention cannot ‘establish the agreement of the parties regarding [the] interpretation’ by all the other [ICSID State parties].”Footnote 45

-

22. A second possibility is that the investment treaty is “relevant rules applicable in the relations between the parties” under Article 31(3)(c) VCLT. Accordingly, the definition of investment in the investment treaty could be relevant for interpreting the notion of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention in so far as the two parties inter se are concerned. In this respect, Article 31(3)(c) is concerned with “the extent to which other treaty relations between the parties may have an interpretative role”.Footnote 46 Gardiner finds some support in the preparatory works of the VCLT that treaties, including bilateral ones, are within the scope of the “rules” that Article 31(3)(c) envisages, but cautions that practice is only “gradually emerging”.Footnote 47 Unlike subsequent agreement or practice above, it is not established that congruence of membership between the treaty that one seeks to interpret and the second treaty that is used to interpret the first treaty is necessary.

-

23. With respect to the “parties” that need to share the interpretation, Pauwelyn argues in the context of the WTO agreements that all the parties to the treaty under interpretation must have assented, at least implicitly, to the second treaty used to interpret the first.Footnote 48 Gardiner, however, notes that practice and academic writing do not lead to “any firm outcome”.Footnote 49 He takes the view that the “omission of ‘all’ combined with the phrase ‘applicable in the relations between the parties’ … makes more sense if referring to relations between the parties having an immediate interest in the issue of interpretation, rather than all states parties to the treaty that is being interpreted”.Footnote 50 The implication is that the definition of investment in the investment treaty may shed light on the meaning of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention.

-

24. A third and much more far-fetched possibility is that the investment treaty’s definition represents an inter se agreement under Article 41 VCLT between two parties to the ICSID Convention in respect of the definition of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention.Footnote 51 This argument is likely to fail because the [Page 39] requirements of Article 41 VCLT are not met. Specifically, Article 41(1)(b)(i) requires that the purported modification “does not affect the enjoyment by the other parties [ICSID member States] of their rights under the treaty or the performance of their obligations”. But if the class of investments covered by Article 25 ICSID Convention were to be amended by inter se agreement, the enforcement obligations of all ICSID member States would increase.Footnote 52 And even if the requirements were met, it would be difficult to show that the investment treaty amounts to a modification. In practice, parties to investment treaties do not notify all the parties to the ICSID Convention that their investment treaty modifies the ICSID Convention, pursuant to the procedural obligation to notify in Article 41(2) VCLT.

C. The inconclusive travaux préparatoires on the definition of investment

-

25. During the period from the 1960s to the 1980s, when investment contracts were the primary instrument of consent for ICSID arbitration, ICSID subject matter jurisdiction was much more straightforward compared with the era of arbitration without privity, from the 1990s until the present, in which investment treaties are the main instrument of consent.Footnote 53 By agreeing to include an ICSID arbitration clause in the investment contract, the host State expressed its view that the specific investment at issue in this particular investment contract qualifies as an investment. By contrast, investment treaties (as well as domestic investment codes) cover a wide range of transactions that are not specified in advance.

-

26. When the ICSID Convention was drafted, no one could foresee the explosion in investment treaty making that followed, particularly in the 1990s.Footnote 54 States had signed only 26 treaties when the Consultative Meeting of Legal Experts that was tasked with drafting the ICSID Convention first met in Addis Ababa in December 1963, and had signed only 39 investment treaties when they signed the ICSID Convention on 18 March 1965.Footnote 55 At the time, only two traditionally capital-exporting States (Germany and Switzerland) had begun their investment [Page 40] treaty programmes: only two of the 26 treaties signed by 20 December 1963, and only five of the 39 treaties signed by 18 March 1965, had neither Germany nor Switzerland as a party.Footnote 56

-

27. The proper interpretation of the travaux préparatoires to Article 25 ICSID Convention on the definition of investment has given rise to sustained controversy. While negotiating the ICSID Convention, States made multiple attempts to define investment but failed due to divergent views on the scope of investment.Footnote 57 It was not surprising that developed and developing countries split on this point.Footnote 58 The lack of a definition of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention was not due to happenstance. Until the end of the negotiations of the ICSID Convention, States had different understandings of “investment”.Footnote 59

-

28. Notwithstanding, the Report of the Executive Directors 1965 expressly noted that “[n]o attempt was made to define the term ‘investment’”.Footnote 60 The same sentence explains that delegates chose not to define “investment” given “the essential requirements of consent by the parties”.Footnote 61 However, the 1965 Report does not mention the wider context of divergent views among the delegates on the notion of “investment” during the negotiations.Footnote 62

-

29. On 9 August 1963, the Executive Directors of the World Bank discussed a “First Preliminary Draft of a Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of Other States”. This first draft did not contain a reference to “investment”, or more generally, to subject matter jurisdiction. The second draft, the “Preliminary Draft Convention” of 15 October 1963, contained a reference to “investment” as a limitation. State experts discussed this draft between December 1963 and May 1964 in four Consultative Meetings of Legal Experts. Based on these meetings, the World Bank prepared a third draft, the “Draft [Page 41] Convention” dated 11 September 1964. The third draft provided the basis for discussions with States in the Legal Committee. This draft also contained a reference to “investment” as a limitation. It defined this notion as follows:

any contribution of money or other asset of economic value for an indefinite period or, if the period be defined, for not less than five years.Footnote 63

-

30. These discussions led to the adopted text of the ICSID Convention, signed on 18 March 1965.Footnote 64 The final version of the text contains the term “investment” but does not offer a definition. All proposals on the meaning of “investment” during the drafting history did not make it into the final text. An unapproved record of the Meeting of the Committee of the Whole on 16 February 1965 reads:

Mr. Broches [World Bank General Counsel and Chairman of the Legal Committee] said that the staff had prepared a definition of “investment” and had also brought to the attention of the Legal Committee a number of examples of definitions of that term taken from legislation and bilateral agreements. None of these had proved acceptable. The large majority had, moreover, agreed that while it might be difficult to define “investment” an investment was in fact readily recognizable. The Report would say that the Executive Directors did not think it necessary or desirable to attempt to define the term “investment” given the essential requirement of consent of the parties and the fact that Contracting States could make known in advance within what limits they would consider making use of the facilities of the Centre. Thus each Contracting State could, in effect, write its own definition.Footnote 65

-

31. Earlier, however, on 25 November 1963, Broches stated the notion of “investment” was not equivalent to State consent to the Centre’s jurisdiction:

[I]n the context of this Convention, the term “jurisdiction” does not mean compulsory jurisdiction, but rather the outer limits within which use can be made of the facilities provided for by the Center. In other words, one is here only concerned with a limitation of the scope of the Convention. Such a limitation is necessary in spite of the fact that the submission of disputes was subject to the consent of the parties concerned, since this Convention was intended to deal, first with a specific field, namely investments, and second with a particular category of disputes, namely disputes between Contracting States and nationals of other Contracting States. This explained why some of the definitions might lack the precision which would be quite essential if one dealt with a case of compulsory jurisdiction.Footnote 66

-

32. These two statements by Broches provide no clear answer on the notion of investment. The unapproved minutes capture the inconclusiveness of the [Page 42] discussions during the drafting of the ICSID Convention. Like the discussions themselves, this summary of the discussion showed that State delegates diverged on the meaning of investment. On the one hand, this summary states that an investment is “readily recognizable” without furnishing a definition (implying that there is an objective meaning of investment). On the other hand, States could write their own definitions (the subjective meaning of investment).

-

33. The formulation “did not think it necessary or desirable to attempt to define the term ‘investment’” in the extract of the minutes above, which also featured in the Draft Report of the Executive Directors,Footnote 67 ended up only a month later in the official Report of the Executive Directors but in the following variation: “[n]o attempt was made to define the term ‘investment’”.Footnote 68 However, the reference to the lack of need and the undesirability of defining “investment” disappeared. To some delegates, the reason for not defining investment was strategic – it was unnecessary and undesirable. However, for others it was the divergent views among States that led an inability to define the term, even though a definition was desirable.Footnote 69 In sum, the travaux to the ICSID Convention shed limited light on the notion of investment, beyond showing that there was much disagreement over what this notion referred to.

-

34. This controversy over whether the meaning of “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention is subjective or objective is important in practice: the more constraining the elements for determining objectively whether a transaction amounts to an investment (to which Section III now turns), the more limited the discretion enjoyed by ICSID tribunals on this matter. Conversely, the more degrees of freedom tribunals enjoy as regards these elements, the less relevant the controversy over the subjective or objective meaning of investment. If tribunals apply the elements very pragmatically, the objective or subjective view changes little to nothing with respect to the jurisdiction of ICSID tribunals.

III. The objective elements of investments

-

35. This Section examines whether there are any objective elements for investments under Article 25 ICSID Convention and, if so, what these elements are according to investment tribunals and the literature. We begin with the travaux préparatoires of the ICSID Convention, before examining three different approaches to the objective meaning of investment: (i) Salini’s positive criteria for investment, or variants thereof; (ii) an almost unlimited meaning of investment, [Page 43] excluding only facially absurd instances not connected to a plausible economic activity; (iii) a negative definition of investments that distinguishes investment, on the one hand, over which ICSID tribunals have jurisdiction, from commercial transactions, on the other hand, over which ICSID tribunals lack jurisdiction. These three approaches can overlap in practice. The Section concludes by looking at the relevance of the objective elements of investments in arbitrations governed by the ICSID Additional Facility Rules, the UNCITRAL Rules and SCC Rules.

A. Objective elements of investments in the negotiations of the ICSID Convention

-

36. Countries disagreed on the need for, and desirability of, a definition of objective elements of an investment during the negotiation of the ICSID Convention, similar to the fault lines that emerged during the negotiations on whether the meaning of investment was objective or subjective (see Section II above). As a rule, developed countries tended to favour a subjective meaning and developing countries an objective meaning of investments.Footnote 70 The travaux préparatoires of the ICSID Convention show that there was no agreement on what the objective elements for identifying investment could or should be – leaving the task of coming up with elements to investment tribunals from the 1990s onwards, and to scholars (the first award where the host State objected to the transaction qualifying as an investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention, and where an ICSID tribunal thus analysed this question in some detail, was Fedax v. Venezuela in 1997).Footnote 71 More fundamentally, during the drafting of the ICSID Convention, countries also disagreed on whether such elements were desirable in the first place.

-

37. Countries have also adopted divergent approaches on the elements for defining investments in their bilateral investment treaty programmes. For example, the UK emphasised the desirability of a definition that was as wide as possible in its bilateral investment treaty negotiations from the 1980s onwards. It also insisted to its prospective treaty partners that the non-exhaustive character of the definition of investment be preserved.Footnote 72 There are no indications that the UK contemplated any implicit objective definition of investment that would require transactions between host States and foreign investors to display certain inherent features.

-

38. In the negotiations on the ICSID Convention, Australia suggested the following definition: “Investment means every mode or application of money [Page 44] which is intended to return interest for profit.”Footnote 73 Germany, which at the time of discussions had already signed around a dozen bilateral investment treaties, which accounted for approximately half of all investment treaties at the time, suggested that the delegates look to existing treaties which “refer to the term ‘property, rights and interests’”.Footnote 74 Mr. Broches rejected this suggestion, as existing “definitions had convinced the draftsmen that they could hardly use them as models since they were always directed towards particular facts or situations”.Footnote 75

-

39. Austria favoured “as general an application as possible”Footnote 76 but also acknowledged the difficulty of having a precise definition of the term.Footnote 77 It underscored the desirability “for the Convention to indicate the meaning of this term in order to define which disputes could be brought before the Centre. A descriptive list might be suitable … public loans or bonds should not be included – but on the other hand, the Convention should cover guarantees given by States to contracts of investment.”Footnote 78 The Austrian delegate explained further:

the definition “legal disputes arising out of or in connection with any investment” is rather vague. It will, of course, be difficult to define precisely the disputes which would fall within the jurisdiction of the Center. Pursuant to Article 26, paragraph 2, the jurisdiction of the Center depends on the consent of both parties to the dispute, and in particular also the consent of the defendant State (same as in the first draft). The new draft, however, no longer provides explicitly the possibility of general statements of submission, as contained in Article 2, paragraph 2 of the first draft. It is doubtful whether the new formulation is an improvement since it should be the goal of the Convention to allow as general an application as possible.Footnote 79

-

40. The five Nordic countries opposed a definition, referring to the futility of attempting a definition. They forecast that few jurisdictional difficulties would arise, and those that did arise could safely be delegated by the parties to ICSID tribunals. Their joint statement shows what also appears to be the final result of the ICSID Convention: States, even if they rejected a definition, still had their own views of what the term “investment” means:

[B]ecause of the condition of consent, there would be no need for complicated definitions. With respect to the term “investment”, the examples circulated by the Secretariat proved how futile it would be to attempt a definition. Since the parties would be free to submit their disputes to the Centre … difficulties would [not] arise in practice and that, should difficulties arise, they should be dealt with by the tribunal. Therefore, [it is preferable that] no definition of the term “investment” be provided for in the Convention. In any case, … the definition included in the present draft suffered from various defects, being both too wide (for instance, seems to include portfolio investments) and too narrow (provides for time limits).Footnote 80

-

[Page 45] 41. Nevertheless, most developing countries underscored the desirability of a definition. For example, China considered the attempt of the World Bank staff to define investment in the Draft Convention of 11 September 1964 “too imprecise and that the condition of consent was too weak to exclude certain undesirable matters from submission to the Center”.Footnote 81 India favoured including “only ‘substantial’ investments” relating “to the total value of the investment rather than to the duration of it”.Footnote 82

-

42. Towards the end of the discussions, the two main proposals – the British and the Spanish proposals – lacked a definition of investment.Footnote 83 Rather than including a narrowly defined list of investments,Footnote 84 the Spanish proposal itself stated that it did not define investment but rather sought a limitation of ICSID’s jurisdiction through other means:

The delegation submitting this proposal understands that to define the concept of investment, in view of the multiple legal economic and financial aspects that it may contain, is a well-nigh impossible task, and it thinks it would be more logical to delimit the action of the Centre, not on a definition of investment, but rather on a definition of competence.Footnote 85

-

43. According to the British proposal, ICSID jurisdiction was limited to investment disputes. Crucially, “investment” was left undefined. To the British proponents, a definition was unnecessary because of an innovative feature that allows each State – at any time – to opt into or out of those disputes which in its view are unsuitable for adjudication by ICSID:Footnote 86

(1) The jurisdiction of the Centre shall extend to investment disputes between a Contracting State and a national of another Contracting State, which the parties to the dispute consent in writing to submit to the Centre. When the parties have given their consent, no party may withdraw its consent unilaterally. (2) Any Contracting State may at the time of ratification or accession or at any time thereafter notify to the Centre the class or classes of investment disputes in respect of which it would in [Page 46] principle consider submitting or not submitting to the jurisdiction of the Centre. Such notification shall not constitute the consent required by paragraph (1).Footnote 87

-

44. The final version of Article 25 ICSID Convention contains a modified version of the British proposal. According to Mortenson, this compromise was “permissive”, charging individual States “with doing the tailoring themselves”.Footnote 88 Based on additional archival research, however, St John shows that this was not the “final word” and that Broches’ (influential) view and the views of the Drafting Committee on this point did not necessarily coincide.Footnote 89 British officials asked Broches for clarification on the definition of investment after the Convention’s entry into force, and in particular noted the lack of certainty on whether the ICSID Convention covered portfolio investors.Footnote 90

-

45. Considering the “well-nigh impossible task” of defining investment,Footnote 91 delegates were unable to reach consensus – and they agreed to disagree.Footnote 92 They chose to include the term “investment” without providing a definition, without agreeing what was meant by the term, and without specifying by which elements investment tribunals should evaluate whether transactions amount to investments. Article 25 ICSID Convention is a good illustration of how States reduce their disagreement to writing.Footnote 93

-

46. Against the ambiguity of Article 25 ICSID Convention on the meaning of investment, three approaches have emerged that we examine in turn: (i) Salini’s positive criteria for investment; (ii) an almost unlimited meaning of investment; and (iii) a negative definition of investments that distinguishes investments from commercial transactions. The following subsections examine these three approaches.

B. The Salini criteria and their critics

-

47. In July 2001, the tribunal in Salini held:

The doctrine generally considers that investment infers: contributions, a certain duration of performance of the contract and a participation in the risks … In reading [Page 47] the Convention’s preamble, one may add the contribution to the economic development of the host State of the investment as an additional condition.Footnote 94

-

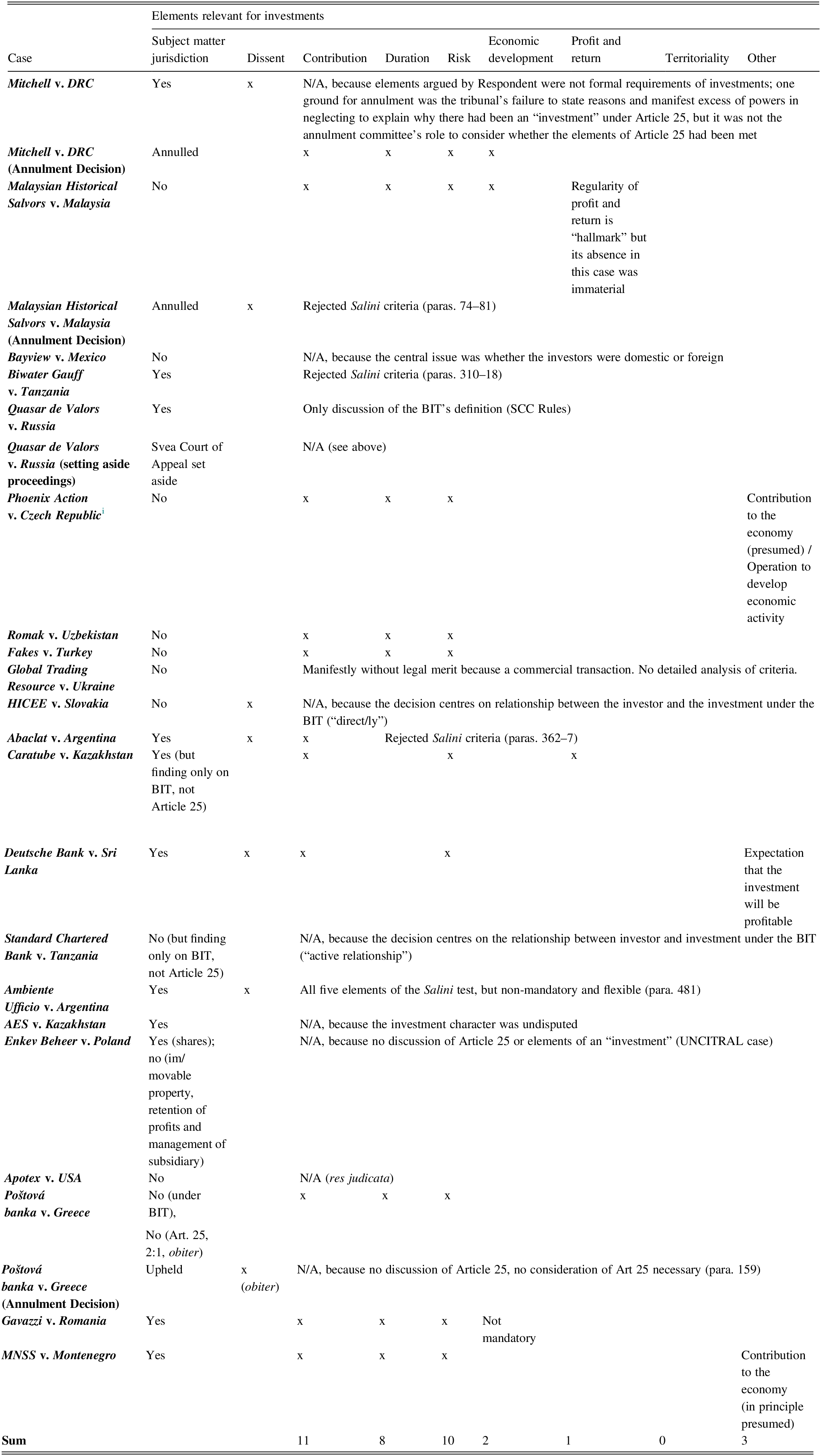

48. Almost 20 years after this decision, tribunals have reduced or expanded these elements of investment, ranging from three to six.Footnote 95 Table 2 provides an overview of which elements tribunals have considered to be relevant for the definition of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention. The awards are in ascending chronological order. Column 2 indicates whether the tribunal affirmed its subject matter jurisdiction, and the remaining columns summarise the approach of the tribunal for each of the six elements: (i) contribution, (ii) duration, (iii) risk, (iv) economic development, (v) profit and return, and (vi) territoriality. The final column includes further observations that do not fit the six other elements.

Table 2 Elements relevant for investments

-

49. There are some common strands of how investment tribunals approach the notion of “investment”: they commonly refer to the interpretive principles in Articles 31 and 32 VCLT when construing the notion of investment;Footnote 96 they frequently invoke the Salini criteria, as well as those of previous decisions; and they emphasise the flexibility of the Salini criteria.Footnote 97

-

50. Schreuer originally identified five elements in the first edition of his Commentary on the ICSID Convention: (i) a certain duration, (ii) a certain regularity of profit and return, (iii) the assumption of risk, (iv) substantial commitment, and (v) significance for the host State’s development. He referred to “characteristics” or “features”.Footnote 98 The Salini tribunal refers mostly to “criteria”, but occasionally also refers to elements and conditions.Footnote 99 This study refers to “elements” of investments. Irrespective of the precise terminology adopted, criteria, characteristics, features or elements are not the same as requirements.Footnote 100 Investment tribunals enjoy some discretion within the bounds that the elements of investment provide.Footnote 101

-

51. This flexibility of investment tribunals means that the lack of a particular element is not fatal to qualifying a transaction as an investment.Footnote 102 With such flexibility comes some discretion for investment tribunals to decide on the [Page 52] contours of the word “investment”. A flexible approach is in keeping with Schreuer’s admonition that the characteristics “should not necessarily be understood as jurisdictional requirements but merely as typical characteristics of investments under the Convention”.Footnote 103 The decisions in this volume illustrate the degrees of freedom that investment tribunals enjoy when it comes to defining the notion of investment:Footnote 104 for example, tribunals rejected the investment character of the delivery of wheatFootnote 105 or of poultry,Footnote 106 but held that that an oil hedging agreement amounted to an investment.Footnote 107

-

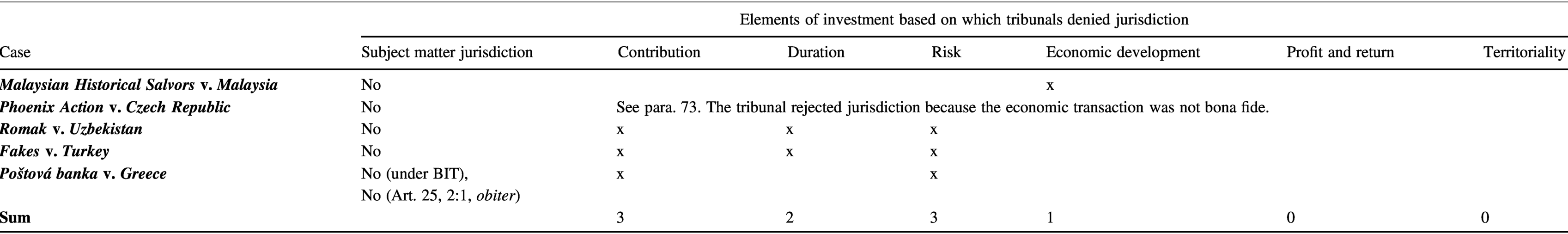

52. For those awards covered in this volume where investment tribunals denied jurisdiction for lack of an “investment”, Table 3 summarises the elements on which these tribunals reached this conclusion. The awards are in ascending chronological order. Five out of 25 decisions reported in this volume fall into this category (the only ad hoc annulment committee that annulled an award for lack of an investment, Mitchell v. DRC, is not shown because the committee by definition did not make any findings on investment; it merely annulled the tribunal’s award). Column 2 indicates whether the tribunal affirmed its subject matter jurisdiction, and an “x” in columns 3 to 8 indicates that the tribunal declined the investment character of the transaction based on the absence of the criterion concerned: contribution (column 3), duration (column 4), risk (column 5), economic development (column 6), profit and return (column 7) and territoriality (column 8).

Table 3 Elements of investment based on which tribunals denied jurisdiction

i. Contribution

-

53. Ten out of the 25 decisions in this volume expressly affirmed that contribution was an element of an investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention.Footnote 108 Only one tribunal (Biwater Gauff) and one ad hoc annulment committee (Malaysian Historical Salvors) expressly rejected this element of an investment (as part of their rejection of the Salini criteria more generally).Footnote 109 The need for a contribution [Page 54] was one of two elements that the Abaclat tribunal accepted, even though it rejected three other Salini criteria.Footnote 110

-

54. Four investment tribunals concluded that there was no investment, based on the absence of a contribution. First, in Romak v. Uzbekistan, a tribunal operating under the UNCITRAL Rules held that a supply contract for the delivery of 50,000 tons of wheat (of which it delivered around 40,600 tons) did not amount to an investment – nor did an arbitral award associated with it – because a mere delivery did not amount to a contribution. While the tribunal defined contribution broadly as “any dedication of resources that has economic value”, “a mere transfer of title over goods” was insufficient for an investment to exist.Footnote 111 The supply contract envisaged immediate performance at the market rate.

-

55. Second, in Fakes v. Turkey, the tribunal found that, because the claimant had never become the legal owner of shares in the second-largest mobile phone company in Turkey, the claimant had not made a contribution.Footnote 112 Third, in Poštová banka v. Greece, the tribunal in an obiter dictum considered that Greek government bonds held by the claimants did not involve a contribution (the ratio of the award was based exclusively on the definition of investment in the investment treaty). According to the tribunal, there was no creation of value, but only an exchange of value akin to a sale because the funds served Greece’s budgetary needs, particularly the refinancing of its existing debt.Footnote 113

-

56. Fourth, in Standard Chartered Bank v. Tanzania, the tribunal found that the claimant was merely a passive owner and had not made the required active contribution under the investment treaty.Footnote 114 A subsidiary of the British claimant bank in Hong Kong was owed a debt by a Tanzanian power company. This debt originally arose from a power purchase agreement for the construction and operating of a power plant in Tanzania. The Hong Kong subsidiary had acquired the debt from a Malaysian company charged with reducing non-performing loans from the Malaysian financial system. Even though the British bank was indirectly linked to the debt via its subsidiary, no British company had made a contribution in Tanzania’s territory. “Owning” or “holding” the purported investment was insufficient. It was necessary for the claimant to take on an active role, such as directing the purchase of the debt (for which there was no evidence).

-

57. In HICEE v. Slovakia, the claimant held indirect, structured investments in two Slovak health insurance companies mediated by a holding company that was also incorporated in Slovakia. The holding company was a direct investment, but the holding company’s shares in the two local insurance companies were only indirect investments of the claimants. Based on the specific language of the investment treaty, and after resolving the ambiguity of this language using the travaux préparatoires,Footnote 115 the tribunal found that the claims with respect to alleged [Page 55] damage to the indirect investment, held by a Slovak company, were inadmissible due to the way in which the investment was made.Footnote 116 These shares were not “an investment of investors of the other Contracting Party”, but an investment by one Slovak entity in two other Slovak entities.Footnote 117

-

58. Awards that focus on passive investments – such as Standard Chartered Bank – and structured, indirect investments – such as HICEE – sit at the intersection of subject matter and personal jurisdiction.Footnote 118 The Standard Chartered Bank award itself is ambiguous on whether disputes about investments “of” investors pertain to subject matter jurisdiction.Footnote 119 On the one hand, the tribunal’s test of whether there was an “active relationship between the investor and the investment”Footnote 120 and the tribunal’s holding “that the investor should have ‘made’ the investment in an active sense”Footnote 121 suggests personal jurisdiction.Footnote 122 On the other hand, the tribunal was not concerned with characteristics of the investment typically associated with jurisdiction, such as nationality, but with how the particular claimant established the investment. Even though the focus on the “activity of investing”Footnote 123 requires an enquiry into the role of the claimant, this approach is rooted in the unity of an investment:Footnote 124 the manner in which the contribution is made (or whether it is made at all) forms part of the process or unity of a putative investment (which is best conceived as an action, activity or process, rather than a static asset) and is thus an issue of subject matter jurisdiction rather than personal jurisdiction.Footnote 125

-

[Page 56] 59. The issue of an investment “of” an investor reflects the same concerns as the Salini criterion of contribution to the development of the host State (see below).Footnote 126 Yet, the focus is on the upstream source of the contribution, rather than on the downstream benefit for development. At both ends of the process, however, the quality of the contribution is at stake – subject matter jurisdiction – rather than the characteristics of the investor (personal jurisdiction).Footnote 127

ii. Duration

-

60. Eight out of the 25 decisions in this volume expressly affirmed that duration was an element of an investment – which is two decisions fewer than for the first element of contribution above. Four tribunals (Abaclat; Biwater Gauff; Caratube and Deutsche Bank) and one ad hoc annulment committee (Malaysian Historical Salvors) expressly rejected this element (as part of their rejection of the Salini criteria more generally).Footnote 128 The element is rarely crucial or decisive: in only two of the reported awards (Romak; Saba Fakes) did tribunals find that the lack of duration was a reason why the transaction did not amount to an investment – but in both cases alongside a lack of contribution and the lack of risk. No investment tribunal thus far has found that a transaction does not qualify as an investment based solely on the missing long-term transfer of financial resources.

-

61. First, in Romak v. Uzbekistan, the tribunal considered that a contract for supplying 50,000 tons of wheat over a five-month period, coupled with the lack of past or future relationship, meant that this was a one-time transaction – rather than an investment with a relationship of longer duration between the claimant and the host State. At the same time, it underscored there was no “fixed minimum duration that determines whether assets qualify as investments”, and that “short-term projects” could so qualify in light of all the circumstances of the transaction.Footnote 129 Second, in Fakes v. Turkey, the tribunal found that because the claimant had never become the legal owner of shares in the second-largest mobile phone company in Turkey, the criterion of a certain duration was not met.Footnote 130

iii. Risk

-

62. Nine out of the 25 decisions in this volume expressly affirmed that risk was an element of investments. Only two tribunals (Abaclat; Biwater Gauff) and one ad hoc annulment committee (Malaysian Historical Salvors) expressly rejected this element for an investment (as part of their rejection of the Salini criteria more generally).Footnote 131

-

[Page 57] 63. Views among investment tribunals and commentators differ as to the kind of risk that is needed for a transaction to qualify as an investment. Some tribunals, such as the Malaysian Historical Salvors annulment committee, consider that any kind of risk, such as the mere risk that the host State fails to perform a contract, suffices.Footnote 132 A second view is that there needs to be sharing of operational risk between the investor and the host State – a view that the tribunals in the following awards adopted. This is sometimes expressly linked to the need for a commercial venture in the host country.Footnote 133 A third view is that the distinction between commercial risk, on the one hand, and investment/operational risk, on the other hand, is irrelevant. Investment treaties protect only against sovereign risk, a type of risk that is unrelated to both commercial and investment risk.

-

64. In Romak v. Uzbekistan, the tribunal distinguished between general business risk and investment risk:

An “investment risk” entails a different kind of alea, a situation in which the investor cannot be sure of a return on his investment, and may not know the amount he will end up spending, even if all relevant counterparties discharge their contractual obligations. Where there is “risk” of this sort, the investor simply cannot predict the outcome of the transaction.Footnote 134

-

65. The tribunal found that Romak had assumed only general business risk (which the tribunal also referred to “as pure commercial, counterparty risk”Footnote 135 ) because the only risk for the claimant was the risk of non-payment for the delivery of wheat. The risk of non-performance was common to all forms of activity but did not suffice for purposes of qualifying a transaction as an investment.Footnote 136

-

66. The tribunal in Poštová banka referred to Romak’s distinction between general business risk (commercial/default risk) and investment risk. Because the claimants transferred funds to Greece that were used for repaying existing debt, rather than for a commercial undertaking, interests in Greek government bonds carried no investment risk.Footnote 137 The tribunal explained further:

Under an “objective” test, the element of risk is essential and cannot be analysed in isolation. Indeed any economic transaction – it could even be said any human activity – entails some element of risk. Risk is inherent in life and cannot per se qualify what is an investment … In other words, under an “objective” approach, an investment risk would be an operational risk and not a commercial risk or a sovereign risk.Footnote 138

-

67. Risk is the element of investment which features prominently in the cases distinguishing commercial transactions from investments (see below). Six of eight [Page 58] decisions that Pahis analyses differentiate commercial transactions from investments based on the character of the risk, among other Salini criteria.Footnote 139

iv. (Contribution to the) economic development of the host State

-

68. Of the 25 decisions reported in this volume, only one annulled award (Malaysian Historical Salvors) and one annulment decision (Mitchell v. DRC) consider that contribution to the economic development of the host State was a criterion of investment. Five tribunals expressly rejected or have not retained contribution to economic development of the host State as a necessary criterion of investment.Footnote 140 Douglas considers that contribution to the host State’s economic development (alongside duration) “generates too much subjectivity”.Footnote 141 In L.E.S.I. v. Algeria, the tribunal held that this element was implicit in contribution, duration and risk.Footnote 142

-

69. The tribunal in Fakes stated that:

Those tribunals that have considered this element as a separate requirement for the definition of an investment, such as the Salini Tribunal, have mainly relied on the preamble to the ICSID Convention to support their conclusions. The present Tribunal observes that while the preamble refers to the “need for international cooperation for economic development,” it would be excessive to attribute to this reference a meaning and function that is not obviously apparent from its wording.Footnote 143

-

70. The tribunal in Deutsche Bank v. Sri Lanka rejected contribution to economic development as a standalone element under Article 25 ICSID Convention in relation to an oil hedge sold by a European bank to a State-owned company in Sri Lanka and governed by English law. According to the tribunal, this element had been “discredited” and was generally considered “unworkable owing to its subjective nature”.Footnote 144 Arbitrator Ali Khan, dissenting, considered that “the substantial commitment or contribution by the Claimant must be made for economic [Page 59] development in the host State”, and found that there was “no contribution or commitment [in this case], let alone any substantial contribution”.Footnote 145

-

71. By contrast, in Mitchell v. DRC, the annulment committee found contribution to the economic development of the host State was “essential”.Footnote 146 This fourth criterion of an investment was the decisive element in this case. The annulment committee explained that

the parameter of contributing to the economic development of the host State has always been taken into account, explicitly or implicitly, by ICSID arbitral tribunals in the context of their reasoning in applying the Convention, and quite independently from any provisions of agreements between parties or the relevant bilateral treaty.Footnote 147

-

72. At the same time, the Mitchell committee underscored that contribution to economic development was a flexible criterion and that investment tribunals were not required to carry out an empirical assessment:

[It] does not mean that this contribution must always be sizable or successful; and, of course, ICSID tribunals do not have to evaluate the real contribution of the operation in question. It suffices for the operation to contribute in one way or another to the economic development of the host State, and this concept of economic development is, in any event, extremely broad but also variable depending on the case.Footnote 148

-

73. The tribunals in Phoenix Action v. Czech Republic and MNSS v. Montenegro chose a third – “less ambitious”Footnote 149 – approach of reframing the contribution to economic development of the host State: both tribunals opted for “a contribution to the economy” of the host State, instead of a contribution to “economic development” as the latter was “impossible to ascertain” given “highly divergent views on what constitutes ‘development’”.Footnote 150 A contribution to the economy could be presumed because it was “inherent in the mere concept of investment”, as reflected in the three main Salini criteria: contribution, duration and risk.Footnote 151

-

74. The claimant’s shares in two Czech companies that traded ferroalloys contributed to the Czech economy, but they did not amount to an investment because the only goal of the purported investment was to rearrange assets within the claimant’s family of companies to transform a domestic dispute into an international dispute. The tribunal gave weight to the “strong indicia that no economic activity in the market place was either performed or even intended by Phoenix. No business plan, no program of re-financing, no economic objectives were ever presented, no real valuation of the economic transactions.”Footnote 152 Thus, the claimant hoped to gain access to ICSID arbitration to which the initial claimant [Page 60] was not entitled.Footnote 153 The claimant did not act in good faith and committed an abuse of rights.

v. Profit and return

-

75. No tribunal viewed profit and return as an element of an investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention. Only one tribunal (Caratube) found that profit and return was an element of investment under the investment treaty. A further award, Malaysian Historical Salvors, that was annulled on different grounds, considered regularity of profit and return a “hallmark” of an investment but that the absence of this element was immaterial in the case of the salvage operation of a vessel sunk in 1817 in Malaysian territorial waters.Footnote 154 Eleven tribunals failed to include this element in their definition of investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention.Footnote 155

-

76. This element, one of Schreuer’s original five typical characteristics, “did not, in general, pose any problems”.Footnote 156 In Biwater Gauff v. Tanzania, the Respondent argued that due to the project being a “loss leader”, it could not qualify as investment. But the tribunal rejected this argument.Footnote 157 It recommended a “more flexible and pragmatic approach”, a holistic assessment of all the circumstances rather than construing the Salini criteria as requirements in one form or another.Footnote 158

vi. Territoriality

-

77. No tribunal viewed a territorial link as an element of investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention. Thirteen decisions reported in this volume omit a territorial element from their definition of investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention.Footnote 159 It is surprising that tribunals do not regard it as an element of investment under Article 25 that the investment be physically located in the host country. That said, some dissenting opinions recognise a territorial element in disputes concerning financial instruments.Footnote 160

-

[Page 61] 78. When investment tribunals do discuss the territorial link, it is by reference to language in the applicable investment treaty. References to “in the territory” in investment treaties are common. Two NAFTA awards under the ICSID Additional Facility Rules reported in this volume (Apotex and Bayview) discuss the territorial element of investment exclusively based on Chapter 11 NAFTA and without reference to Article 25 ICSID Convention.

-

79. An early award that adopted a very broad reading of territoriality was Fedax v. Venezuela. It sufficed that “funds were made available … to the beneficiary of the credit [i.e. Venezuela] so as to finance [Venezuela’s] various governmental needs”.Footnote 161 The Fedax approach on this issue has influenced later investment tribunals, particularly in the three Argentine bond cases.Footnote 162

-

80. In Abaclat v. Argentina, the territorial element was important because security entitlements in Argentine sovereign bonds governed by an external law and subject to the jurisdiction of external courts were at issue. The Abaclat tribunal considered that the situs of the debt was in Argentina because what mattered was for whose benefit the funds were used. Because the funds were available to Argentina and supported Argentina’s economic development, the territorial element was satisfied.Footnote 163

-

81. The tribunal in Ambiente Ufficio adopted a similar approach regarding the territorial element in the BIT. It considered that the “decisive criterion cannot be whether [the bonds] are physically located in Argentina”, as they differed qualitatively from “physical investments”.Footnote 164 The State that benefited from the transaction was automatically the one in whose territory the transaction has been made: “to assess where an investment was made, the criterion must be to whose economic development an investment contributed”.Footnote 165

-

82. According to the Romak tribunal, the mention of “territory” in the preamble of the applicable investment treaty does not warrant an independent element of territoriality. Instead, the tribunal analysed territoriality “in light of” the three [Page 62] elements that it identified as inherent in the meaning of investments under the BIT for UNCITRAL and ICSID proceedings: contribution, duration and risk.Footnote 166 The tribunal explained:

Although the BIT contains numerous references to the “territory” of the Contracting States, the Arbitral Tribunal notes that Article 1(2) of the BIT, which defines the term “investments,” does not. The Arbitral Tribunal can identify no treaty provision requiring that the investor’s contribution physically take place within the boundaries of the host State to trigger substantive protection … unless contracting States have made “territoriality” an express pre-requisite for treaty coverage (which is not the case in the BIT), references to “territory” normally refer to the benefit that the host State expects to derive from the investment.Footnote 167

-

83. In Bayview, a NAFTA tribunal operating under ICSID Additional Facility Rules considered rights of the claimants in the United States to extract water flowing through the Rio Grande/Río Bravo.Footnote 168 They contended that these rights amounted to investments in Mexico. The tribunal’s analysis focuses on whether claimants had an investment in Mexico.Footnote 169 The tribunal declined jurisdiction because the claimants’ investments were physically located in the United States rather than in the host State. The claimants had no personal property rights in the water flowing through the river on Mexican territory.Footnote 170

-

84. In Apotex, another NAFTA tribunal operating under ICSID Additional Facility Rules considered obiter in response to the host State’s alternative argument that the investment must be “in the territory” – though this was immaterial because the tribunal would have reached the same conclusion. The tribunal held that marketing authorisations by the US Food and Drug Administration were not an investment in US territory “particularly” because of the lack of a physical presence and the absence of tax payments.Footnote 171

vii. Investments in accordance with the laws of the host State or good faith investments

-

85. Tribunals have adopted two divergent approaches on whether the legality or the good faith character of an investment pertained to the definition of investment. There is a distinction between the qualification of an “investment” (for which legality/good faith is irrelevant) and the protection and coverage of the ICSID [Page 63] Convention (for which legality/good faith are relevant).Footnote 172 The first concerns jurisdiction, the second admissibility.Footnote 173 Whereas legality as a matter of definition concerns only jurisdiction, legality as a matter of coverage can concern either jurisdiction – if the definition of investment is met but a further requirement ratione materiae for the perimeter or scope of the treaty is not met – or admissibility – if the tribunal deems jurisdictional hurdles met but that it should not use its adjudicative power. The tribunal in Fakes stated:

the principles of good faith and legality cannot be incorporated into the definition of Article 25(1) of the ICSID Convention without doing violence to the language of the ICSID Convention.Footnote 174

-

86. By contrast, the tribunal in Phoenix Action v. Czech Republic held that ICSID tribunals only have jurisdiction with respect to transactions that are in accordance with host State law and are bona fide investments.Footnote 175 While the investor had not breached Czech law on the facts and thus complied with the first requirement, it made the investment not to engage in economic activity, but to transform an existing domestic dispute into an international one. The tribunal thus rejected its jurisdiction for lack of the second requirement (no bona fide investment). The consequences of the investor’s lack of good faith (abuse of rights) differ depending on whether: (i) a tribunal rejects the qualification as “investment” itself, as in Phoenix (no jurisdiction); or (ii) protection of the treaty is rejected, as in Philip Morris v. Australia (the claim is inadmissible).Footnote 176

C. The new objectivism: objective in name only

-

87. A second approach contends that the meaning of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention is almost limitless. This new objectivism, of which Julian Mortenson is a leading exponent, argues against any positive elements for investment such as the Salini ones examined above. Mortenson construes investment as broadly as possible with “near-total deference to state definitions of ‘investment’” in investment treaties,Footnote 177 excluding only “facially absurd” definitions.Footnote 178 He concludes that “ICSID has jurisdiction over any plausibly economic asset or activity”.Footnote 179 He gives the following example of an excluded transaction:

[Page 64] If a teenage backpacker slips and falls on public streets during a summer trip to New Zealand, she should not be able to bring an ICSID claim based on her “investment” of time in the country.Footnote 180

-

88. This illustration of a facially absurd investment is reminiscent of Douglas’ example of a metro ticket seemingly qualifying as an investment. He contends that qualification of the ticket as an investment would do violence to the economic meaning of investment, even if such a ticket could be said to fulfil the legal elements for an investment. Douglas, in contrast to Mortenson, contends that:

“investment”, however, is a term of art: its ordinary meaning cannot be extended to bring any rights having an economic value within its scope, for otherwise violence would be done to that ordinary meaning, in contradiction to Article 31 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. The right to performance embodied in a metro ticket cannot qualify as an investment.Footnote 181

-

89. Even investment treaties with broad, asset-backed definitions of investment – for instance by including “claims to money”,Footnote 182 “obligations” or “any right of an economic nature granted by law or by contract”Footnote 183 in their definition of investment – probably do not cover such “absurd” definitions of investment. Such absurd examples apart, under this approach, it is the investment treaty that is decisive. The reference in Article 25 ICSID Convention to “investment” does little, if any, work, rendering it superfluous.

-

90. Mortenson’s analysis relies heavily on the common mischaracterisation of the statement in the Report of the Executive Directors 1965 that “[n]o attempt was made to define the term ‘investment’”.Footnote 184 In contrast, as discussed above, there were multiple attempts to agree on a definition, but a consensus failed to emerge. According to Mortenson, the British proposal of including no definition of “investment”, but providing for a mechanism of excluding certain disputes under Article 25(4) ICSID Convention, shows that the drafters opted for an extremely broad definition of investmentFootnote 185 that covers “any plausibly economic activity or asset”.Footnote 186 Consequently, applying the Salini criteria (or any other substantive elements) for the second leg of the test for investment is mistaken. Based on the drafting history, there is no need for the second leg of the test.

-

91. The Ambiente Ufficio tribunal adopted this approach. It cited Mortenson several times in support of its broad interpretation of the term “investment”. In particular, the tribunal relied on Mortenson’s reading of the 1965 Report of the Executive Directors on the ICSID Convention and the possibilities for States to [Page 65] restrict the broad meaning of investment in Article 25 ICSID Convention through Article 25(4) notifications.Footnote 187 The tribunal explained that

The very citation from the Report of Directors referred to above testifies to this trade-off when it expressly links the lack of a definition of “investment”, first, to the “essential requirement of consent by the parties” and, second, to the “mechanism” of Art. 25(4) of the Convention. However, the Report’s wording is inaccurate inasmuch as the non-existence of a definition of “investment” in Art. 25(1) of the ICSID Convention was due to a deliberate abstention from including a definition rather than to a failure to agree on a definition. It is inaccurate inasmuch as the non-existence of a definition of “investment” in Art. 25(1) of the ICSID Convention was due to a deliberate abstention from including a definition rather than to a failure to agree on a definition.Footnote 188

-

92. While not relevant to its decision, the tribunal did not adopt Mortenson’s expansive view of investment under Article 25 ICSID Convention as regarding “any plausibly economic activity or asset”. In obiter, the tribunal expressed a preference to exclude commercial transactions from the notion of investment (see paras. 97–103 below).

-

93. The mechanism in Article 25(4) ICSID Convention for excluding disputes does not mean that the notion of “investment” is “nonjusticiable” – that is, that the presence of this mechanism precludes ICSID tribunals from drawing “outer limits” of the term investment.Footnote 189 Article 25(4) ICSID Convention speaks of disputes which can be excluded – not investments.Footnote 190 The original, co-sponsored British proposal spoke of “investment disputes” for jurisdictional purposes (in what became Article 25(1) ICSID Convention) and of “class or classes of investment disputes” in relation to possible exclusions by notification (now Article 25(4) ICSID Convention).Footnote 191 At the time of writing, only seven ICSID member States – all developing countries – had made such notifications.Footnote 192 In some cases, States limited disputes to approved investments.Footnote 193 Yet States also exclude sectors or they limit the applicability of treatment standards such as expropriation. [Page 66] Put differently, this mechanism of exclusion under Article 25(4) ICSID Convention is not limited to transactions that do not qualify, in the view of the excluding State, as an investment.

-

94. The same reasoning applies to the two other methods which States could use to limit their exposure to investment arbitrations: (i) reservations to the ICSID Convention;Footnote 194 and (ii) narrow definitions of “investment” in their investment treaties.Footnote 195 Just because States can exclude certain disputes under Article 25(4) ICSID Convention, because they may enter a reservation, or because they may define investment in their investment treaties narrowly, does not imply that “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention needs to be interpreted narrowly or broadly. The possibility of excluding certain disputes does not substitute for State consent.Footnote 196 This first approach renders “investment” in Article 25 ICSID Convention superfluous and deprives it of any real meaning – which is not in keeping with Article 31 VCLT.Footnote 197

-