The previous chapter introduced the historical driver of my argument about why we are seeing the emergence of disparate local redistributive strategies in rural Senegal: variation in exposure to precolonial statehood. Core to my argument, however, is the idea that these precolonial legacies interact in unforeseen ways with subsequent institutional reform. Accordingly, this chapter takes up the task of laying out the two remaining historical foundations of my argument. I begin by introducing Senegal’s system of decentralized local governance, which intersects with the country’s precolonial political geography to generate institutional congruence or incongruence. The second half of the chapter explores the third empirical building block that relates to the unit of analysis itself: how were the boundaries of Senegal’s local governments drawn? If what is critical is how elites relate to each other across villages, then the argument risks being endogenous to the very social relations that benefit local governance today if some communities were able to self-select into a local state with their friends and family. Drawing on archival and interview data, I find scant evidence that boundaries were systematically driven by bottom-up social dynamics. In contrast, the material suggests that decentralization reforms were implemented from above, in some cases netting villages with shared social institutions of cooperation and reciprocity into new administrative units, while in others grouping together villages with no meaningful shared history. Taken together, this historical detail enables me to explain why Senegal’s decentralization scheme structures distinct cross-village social dilemmas across the country.

The Structure of Governance in Postcolonial Senegal

Centralizing Tendencies in the Senegalese State

Senegal gained independence from France in 1960. The newly independent nation inherited a highly centralized colonial state and, under the leadership of the country’s first president Leopold Sedar Senghor, the government pursued nation-building and economic development through a statist and socialist model. This had three consequences for the decentralization reforms that were to follow. First, it centralized power around the executive and within the ruling Socialist Party (Parti socialiste or PS). This concentrated political competition from the national to the local level within the party itself, as political disagreement manifested in party factions or “clans.” The drafting of a new constitution in 1963 further consolidated the “winner-take-all electoral regime” and rendered even prestigious ministerial posts mere “high-level functionaries.”Footnote 1

Senghor’s “amalgam” party apparatus was largely built on relations of convenience rather than a serious adherence to socialist ideology.Footnote 2 The second defining feature of the postcolonial regime was the patronage ties Senghor reinforced with local brokers as Senegal became a clientelist regime par excellence. As Boone (Reference Boone1992, 98) writes, “power relations in the rural areas that were rooted in long-established social hierarchies and relations of production constituted the regime’s most solid and reliable bases of political power.” This largely continued a pattern set in the colonial era, when Sufi marabouts and other traditional leaders built and maintained their authority by cultivating relationships with elites in Dakar.Footnote 3 Even as the regime centralized, therefore, it did so via local brokers, most famously the Mouride Brotherhood, introduced in the previous chapter.

In an early challenge to the regime, Senegal saw a constitutional crisis in 1962 that was marked by a falling-out between Senghor and his Prime Minister, Mamadou Dia, largely attributed to Dia’s more radical vision of reform than that held by Senghor, who was wary of directly challenging the regime’s clientelist network. Part of Senghor’s disagreement with Dia was over the regime’s ambitious rural outreach program, animation rurale, which aimed to bring the peasantry into the modern economy by improving their access to modern agricultural practices and social services.Footnote 4 While making inroads in the regions of Casamance and Fleuve (present-day Saint-Louis and Matam Regions), the program met resistance in the heartland of the country’s peanut basin, where local brokers and religious authorities saw the program as a challenge to their authority. Senghor’s solution was to imprison Dia and eliminate the position of prime minister, a political maneuver his regime was able to weather precisely because he maintained the support of the Mouride leadership throughout.Footnote 5 In turn, animation rurale shifted toward less radical goals, emphasizing agricultural production over social reform.Footnote 6

Cumulatively, this centralization of power and the subverting of the regime’s stated development goals to the exigencies of its clientelist relations produced a third consequence: the crisis of le malaise payson that beset the country in the early 1970s. Despite the fact that the state had already begun to back away from the ambitious – and costly – expenditures associated with animation rurale, Senghor’s patronage system was under pressure.Footnote 7 Groundnut production, the state’s primary export commodity, fell short of projected growth, inhibiting Senghor’s ability to generate the necessary revenue to keep the centralized clientelist system running smoothly. Despite the young state’s vast ambitions, the cooperatives established by animation rurale had neither transformed the lives of rural producers nor produced rapid economic growth. In sharp contrast, peasants had used these services opportunistically at best.Footnote 8 As the promised benefits of the socialist regime floundered, rural producers became increasingly vocal in their dissatisfaction.Footnote 9

Decentralization in Three Acts

Senghor responded to this crisis in 1972 by announcing the creation of a new administrative unit below the arrondissement: the rural community (le communauté rurale). Diouf (Reference Diouf and Diop1993, 237) quotes Jean Collins, the Ministry of the Interior at the time:

over the past several years it has become clear that the rural population has not really been involved in our administrative structures … That means that only a tiny minority of the population participates. It is just as clear that if administrative activities are to be carried out with genuine efficiency, they have to be based on the active, responsible involvement of the population. After all, they are in the best position to assess their own needs.

Now known as Acte I, the creation of local governments made Senegal an unwitting trailblazer for decentralization in the region. Designed to improve the ability of state officials to respond to local needs and unrest while simultaneously appeasing PS brokers by deconcentrating the power that Senghor had amassed in the presidency, the government rolled out 320 local governments over a ten-year period between 1974 and 1984, beginning in the peanut basin where the rural citizenry was most vocally unhappy.Footnote 10 Each local government was comprised of numerous villages, collectively run by locally elected rural councils (le conseil rural). Although local elections began in 1978, one-third of seats were allocated to state agents, while the remaining two-thirds were elected from the single party lists assembled by local PS party branches. At the head of the local government council sits the influential Rural Council President (le président du conseil rural) – today known as the mayor – along with two vice presidents.

Acte I granted local authorities the right to prioritize local needs, but because rural communities were subject to the tutelle of the central state and hence not autonomous actors, actual decision-making remained with the central-state-appointed subprefect (sous-préfet), based in the next highest administrative unit, the arrondissement. This effectively ensured central government control of rural development initiatives. What Acte I did offer was the transfer of authority over land allocation to local councils. Land had been moved out of the customary domain and to the central state with the 1964 Loi sur le domain national, but the 1972 decentralization law transferred authority over allocating uninhabited or unused land for farming or herding to the rural council, quickly making it the most significant source of power for local councils.Footnote 11

In 1996, Senegal’s second president, Abdou Diouf, announced Acte II of the country’s decentralization reforms and transferred substantial new fiscal and developmental authorities to local governments. Diouf’s reforms built on the country’s first phase of decentralization, but profoundly shifted the nature of local governance by introducing three major changes. First, all council seats became subject to popular vote, though the country remained dominated by the PS until the election of President Abdoulaye Wade with the Parti démocratique Sénégalais (PDS) in 2000. As a result, a number of parties contested and were elected in the 2002 local elections.Footnote 12 Local elections had originally been based on proportionality, but Acte II introduced a mixed proportionality–plurality model. To the present, half of local council seats are allocated proportionally, while the other half goes to the majority winner, thus that even if the second place party obtains 49 percent of votes, they hold at most 24 percent of seats. Not surprisingly, this results in considerable premium being placed on obtaining a majority and, once earned, the ruling party has substantial say in decision-making.Footnote 13 Councilors are elected from party lists with the entire local government functioning as a multimember district. Following the popular vote, the mayor and his two adjoints are elected indirectly by their fellow councilors at the first meeting of a local council’s new term.

These changes to the council’s political dynamics are particularly consequential in view of the second major policy change in 1996: Acte II enlarged the local council’s authority to nine policy areas, including the responsibility to prioritize and implement the construction of high-demand basic social services, such as classroom and clinic construction.Footnote 14 Consequently, local councils have full legal autonomy within the decentralized sectors.Footnote 15 Today, most local governments are not active in all nine of the domains, though all local councils run activities in health, education, and many implement programs in the areas of youth and culture in addition to distributing and adjudicating issues surrounding land access.

The central government appoints a local government secretary, or Assistant Communitaire, to each local government to help with paperwork, but we should be careful to not overestimate the planning capacity of local governments, which suffer from weak tax receipts, poor training, and meager transfers from the central government in proportion to their devolved areas of authority. Still, even though local officials like to quip that the central state transferred “the nine biggest problems in the country, with none of the means,” local governments are able to engage in a number of yearly activities, such as providing school supplies at the start of each school year, building new classroom blocks or health clinics. Combined with resources that may enter a community through donors, this can result in a number of “small” improvements over a five-year term.Footnote 16

The third major change introduced by Acte II was the transfer of fiscal resources to local governments, including the local government’s ability to collect a series of taxes. Most councils only collect the rural tax (la taxe rurale, still referred to in many areas by the colonial nomenclature, l’impot) and, less frequently, taxes on local market stalls or parking.Footnote 17 Many local governments collect almost nothing in a given year, but even those who do raise the rural tax have to rely on other financial sources to actually implement projects.Footnote 18 The key revenue source of local governments is then by default central government transfers, which cover operating costs and a few development investments per year. The central transfer, the Fonds de Dotation de la Decentralisation (FDD) averaged between $22,000 and $28,000 in 2013, for example.Footnote 19 Together, this means that Acte II granted local councils expenditure autonomy for investments in capital or maintenance, while key patronage activities, such as staffing rural administrations, remain firmly within the control of the central state.Footnote 20

The arrival of Acte II – with its new resources and autonomy – dramatically altered the incentives facing local elites, reorienting their behavior toward the local state. The ability to target villages with a school or clinic is an unparalleled source of local patronage, thus that even if financing is insufficient, it is nonetheless non-negligible. And while local governments make varied investments, such as building a football pitch for a youth league or buying millet mills to alleviate women’s labor, their most significant accomplishments in a given term are almost always the construction of major infrastructure.Footnote 21 Demand for new public goods, like new schools, additional classrooms or clinics, should not be underestimated. Requests such as one chief’s in Kaolack Region, that the local council “should build us a school so that we have our own and so that our children do not have to walk two kilometers to the school …” are heard throughout the countryside.Footnote 22

Still, Acte II was far from a perfect reform and local politicians articulate lengthy reclamations from the state; local governments need more funding, more technical assistance, more training, and more central state support. When President Macky Sall introduced a new set of decentralization reforms, Acte III, in December of 2013 – intended to harmonize decentralization and encourage localized direction of economic and social development – local politicians anticipated long-awaited improvements to their working conditions.

The most immediate outcome of Acte III was the elimination of disparities between decentralized political units. The country was home to urban and rural communes under Actes I and II, but Acte III brought communalisation integral, creating urban and rural communes alike, a long-desired goal among rural politicians. Still, uncertainty around the changes generated substantial skepticism. “I think Macky Sall enacted Acte III just so he could leave his own footprint on decentralization in Senegal,” remarked one local development agent cynically, given that “Senghor created it, Diouf undertook Acte II, even Wade made his mark …”Footnote 23 In the short term, Acte III generated substantial confusion over financing, resulting in a common lament that President Sall enacted the reforms “too fast” and with insufficient attention to the financial resources available to local governments.Footnote 24 “All we felt here was a change in name,” one adjoint mayor commented in 2016, noting that federal government transfers had remained the same while citizens’ expectations about the role of the local state continued to expand. “We cannot wait for the texts while the population is there waiting … we cannot just cross our arms and wait on Dakar,” he surmised.Footnote 25

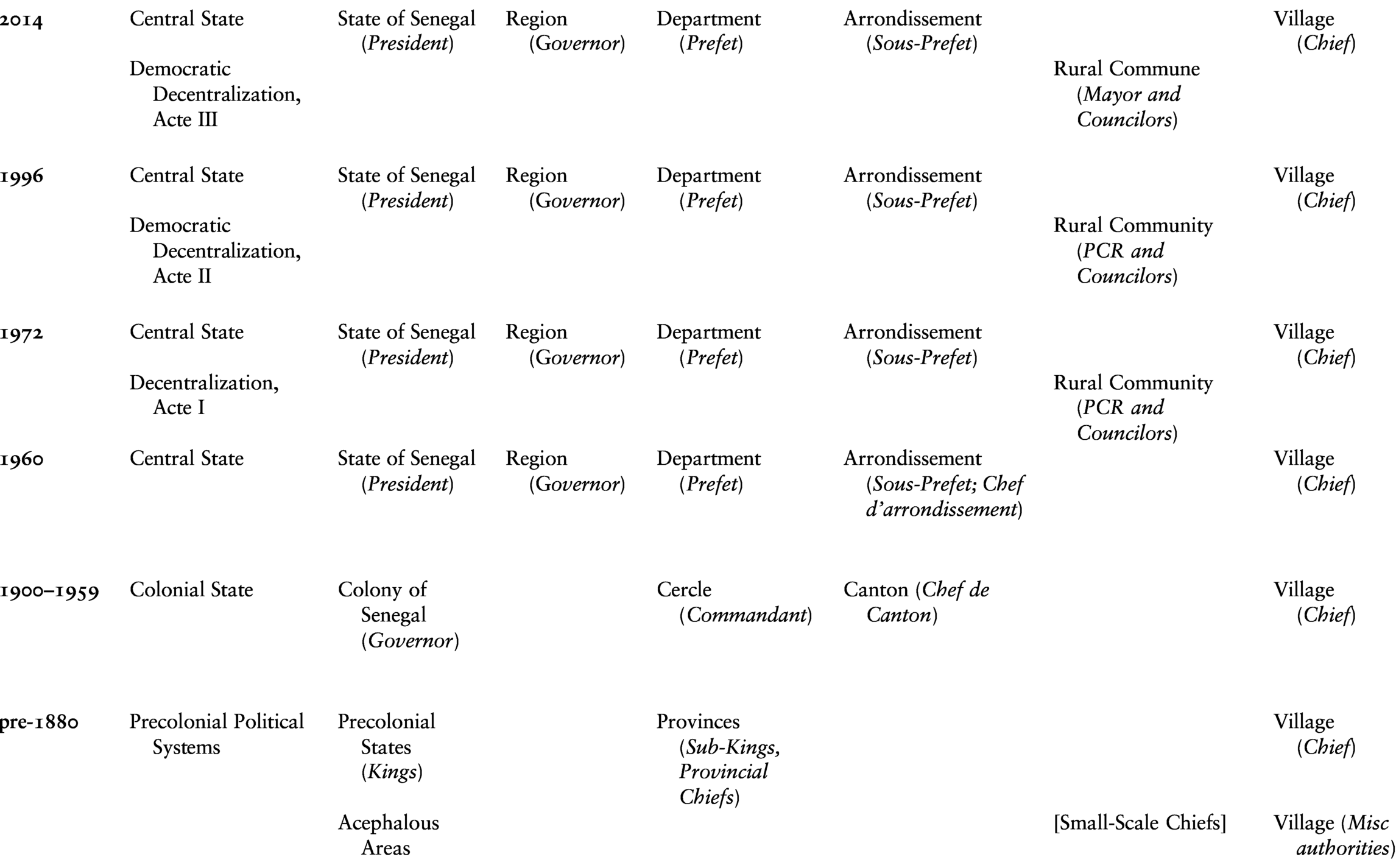

These changes in Senegal’s administrative hierarchy over time are summarized visually in Table 3.1. Note that the changes brought by Acte III of decentralization in 2014 do not fundamentally change the structure of local government, but rather the nomenclature alone.

Table 3.1 Administrative hierarchies over time, with relevant officials in italics

As introduced in Chapter 1, I conceptualize the introduction of elected, decentralized governments as creating a form of a two-level game. This is illustrated well in Table 3.1. Local elites who pursue elected office face two levels of play: their local governments are comprised of numerous villages, within which they seek and retain clients, promising local government goods in exchange. Yet at the second level of the local state itself, local elected officials find themselves facing a second political arena. Here, elected officials must adjudicate between the competing demands of the many villages that comprise the local state, generating distinct negotiations over which villages receive which investments. Evidence of this dilemma can be found elsewhere in the region. Koné and Hagberg (Reference Koné, Hagberg, Hagberg, Kibora and Korling2019, 44), for example, observe how the legitimacy of a local government candidate in Mali’s decentralized system rests on two levels: candidates cannot be seen as neglecting their extended family and social network on the one hand, but on the other they cannot risk completely favoring them either, generating a precarious balancing act for local candidates. This means that a local elected official’s preferences vis-à-vis their home village, their co-ethnics, or their extended family are not always the best choice for their political party or allies in the arena of the local state. Senegal’s decentralization reforms have delivered valuable patronage for local politicians to distribute across the villages of the local state, but by asking village-based elites to compete at the level of a newly created local state, the devolution of authority to democratically elected local governments has generated unique redistributive dilemmas that, as the following chapters show, are resolved in structurally distinct ways across the country.

Central–Local Relations under Decentralization

To the extent that Senegalese politics was long defined by a centralized administration with extensive clientelist relations to rural brokers, how has the increased responsibilization of local governments impacted central–local relations? Certainly, national politics loom large across the country and rural Senegalese eagerly debate shifting party alliances and the fates of favored politicians. Nonetheless, the general impression across rural Senegal is that the central state uses rural areas opportunistically. This is not lost on local actors. For example, it is widely acknowledged that the redistricting of many localities prior to the 2009 elections was motivated by central state ambitions. “The redistricting was only political,” sighed one community secretary whose local government had been placed under a special delegation following the elevation of one of the local government’s larger villages to the statute of an urban commune. Because the mayor was from the opposition, she continued, the regime of former President Wade had rewarded a partisan ally in the now urban commune, punishing opposition politicians based in the former local government’s remaining villages.Footnote 26

This does not make rural actors mere passive recipients of state action, however, and the relationship between the central and local state is far from top-down. In contrast, even if many individuals cynically remark that national parties use local elections as de facto mid-term barometers of their popularity, local electoral fortunes are heavily influenced by local political dynamics.Footnote 27 Spots on local electoral lists are widely ascribed as going to those with local “electoral weight.” As one chief described, it helps a candidate if they are well-known and have a history of doing good work in the community because this inspires “confidence.”Footnote 28 This means that rather than national parties endowing any given local actor with electoral power by virtue of offering their party affiliation, local politicians who have “mass” behind them are highly valuable allies that national parties seek out. As a mayor in Dagana Department remarked, “locally, it’s the person that counts” not the party.Footnote 29 This renders partisan attachments fleeting; when asked about local partisanship, one chief summarized pithily what many spoke of across the country, “we follow our leader [the mayor] and right now he is with the APR.”Footnote 30

One consequence is that Senegalese politicians prioritize winning by large margins, rather than pursuing a minimum winning coalition.Footnote 31 Indeed, it is far more common for local party leaders to speak of the need to “massify” their parties than to narrowly target certain segments of the electorate. As one community secretary wryly commented, “politics is all about who has the people behind him.”Footnote 32 This means that party affiliation and coalitions at the local level are in many ways a function of the availability of prominent local politicians. Take, for instance, one subprefect’s prognosis for the 2014 local elections: the mayor of the local government I had visited in his arrondissement was, in his opinion, “strong enough” to run with the APR alone. But elsewhere in his district, he commented, incumbents were weaker and would need the help of the broader presidential coalition, Benno Bokk Yakkar. Indeed, he observed, the dynamic would be much the same as in other local elections he had observed since 1996: “everyone needs to consolidate their base to have a chance … they need local party militants” and this, he continued was largely a function of a politician’s own “strengths” and not their party.Footnote 33

The 1996 reforms were a dramatic shift from the early centralizing tendency of Senghor’s regime, therefore, but despite the extent that local governments have become important sites of political contestation, they remain in their own unique local venues. In contrast and substantiated in the qualitative data marshaled in the following chapters, local politics is animated by distinct logics that call into question the idea that the central government and national level parties “telecommand” the local state.

Drawing Boundaries in the Countryside

Chapter 2 established that rural Senegal is home to durable social hierarchies rooted in histories of village settlement. This raises the possibility that local governments in historically centralized and acephalous areas never faced comparable redistributive dilemmas at all. Is variation in local governance endogenous to the ability of historically centralized communities to select into a meaningful administrative unit in the first place?

Political scientists have only rarely theorized the spatial origins of territorial units, despite the fact that borders may in many cases be a result of the very political processes we study.Footnote 34 What attention has been paid to this question has focused on the nature and repercussions of Africa’s national boundaries.Footnote 35 Less attention has been paid to subnational boundary-making, however, despite Posner’s (Reference Posner2004a) well-known conclusion that the legacies of colonial boundary-making are as much domestic in nature as they are international because subnational administrative boundaries put social and cultural identities into particular relief. In South Africa, for example, the fact that local jurisdictional boundaries lay arbitrarily on top of the territory of traditional authorities has generated substantial contention.Footnote 36 My argument asks us to think seriously about the question of boundary delimitation specifically because the politics that boundaries enable or obscure hold profound consequences for citizens.

Below, I trace the history of subnational boundary delimitation from the colonial period to the present through archival documents and interviews. Of course, it is implausible that subnational boundaries are as-if random but examining the history of boundary creation does suggest that there is no clear path by which precolonial provinces or territories have either persisted or been reinvented following decentralization. In sharp contrast, redistricting has almost exclusively been done as a means to obtain the objectives of the colonial or postcolonial central state, such as rendering the population more legible or political coalition building. I find minimal evidence that they systematically incorporated local preferences, reducing concerns that local government boundaries were systematically structured by bottom-up preferences of local elites.

Colonial Boundary-Making

The early years of colonialism were marked by French efforts to create usable administrative units for the colonial project.Footnote 37 In 1895, the French administration divided Senegal into cercles and, three years later, they created cantons, the base unit of French colonial governance, within each cercle. Cantons were intended to mirror France’s own départements, “neat logical units with approximately the same size and population,” but in reality, administrators were quite practical, at times co-opting precolonial provinces and cantons as described to them by customary authorities, while at others creating units around principles of ethnic homogeneity or by relying on geographic markers.Footnote 38

General William Ponty’s 1909 Politique de Race was the first significant articulation of France’s policy toward their new colonial subjects, arguing that France should create similarly sized cantons of homogenous religion or ethnicity and abandon precolonial structures, which he viewed as “arbitrary groups created by the tyranny of local chiefs.”Footnote 39 In large part, this was the consequence of French skepticism of indigenous African authority, meaning that even if early years saw the French seeking out reliable “aristocratic” intermediaries, this initial reliance on precolonial understandings of territories quickly eroded as Cartesian principles seeped in.Footnote 40 This generated strange hybrids in the short term. Administrators proposed two provinces, all comprised of five to six cantons, for each of the precolonial kingdoms of Baol, Saloum, and Sine, for example. In other cases, they stressed administrative ease, citing a need to balance the population evenly across units and to avoid unmanageable territorial expanses.Footnote 41 Plans to merge a series of cantons in the former kingdom of Sine in 1925 were met with outrage unforeseen by the French, who assumed that everyone being Serer and loyal to the Bour (king) of Sine would make their consolidations acceptable.Footnote 42

Different strategies had to be employed altogether in historically acephalous areas, where colonial administrative units often had no geographic or political significance.Footnote 43 Borders in Senegal Oriental (present-day Tambacounda and Kedougou Regions) long remained imprecise, relying on natural features, such as rivers, or straight lines to delineate cantons.Footnote 44 Ten cantons were created in Bignona, but only in Tendouck Arrondissement did any of them reflect any degree of ethnic homogeneity.Footnote 45 In the Fouladou in the Haute-Casamance (Kolda Region), the French sought meaningful indigenous political organization, but the administration fundamentally misunderstood the loose ties between ruling families and ended up creating eleven cantons that failed to correspond either to precolonial understandings of territory or to produce the political acquiescence they desired.Footnote 46

As the colonial state bureaucratized, the administration continually sought to improve their territorial organization.Footnote 47 To take the year 1924 as an illustration, the French made the following changes in that year: the canton of Nioro Rip was reattached to Wack and Rip and Pakalla-Mandakh was reattached to Ndoukoumane in Saloum. Twelve new cantons were created in Casamance and while Sandock Diagagniao was merged into Sao-Ndimack in Tivaouane, La and Ndoulo were split in Baol.Footnote 48 Redistricting was done to meet a myriad of objections. The broad demographic changes induced by colonialism – notably the rapid conversion to the Mouride Brotherhood as well as the expansion of the colonial economy – spurred territorial changes driven by economic motivations.Footnote 49 By way of illustration, the canton of Meringahem was reassigned to Louga cercle in 1928 due to its population’s reorientation toward Louga’s economic centers for the sale of their peanut crops; “administrative divisions should correspond as exactly as possible to the economic regions created by the implementation of colonial rule,” justified the French Chef de Cercle.Footnote 50 Diplomatic objectives were also pursued – a proposal in 1953 to merge the cantons of Kadiamoutayes-Ouest and Kadiamoutayes-Sud-Est (originally split as “a matter of personal satisfaction … and subsequent administrative instigations, but not one of real political or economic interest”) was rejected due to the perceived need to amplify France’s administrative presence along the colony’s southern border, where the two cantons lay.Footnote 51 Alternatively, the sheer inability to locate reliable intermediaries resulted in the merging of numerous cantons at various points of time, particularly in historically acephalous areas.Footnote 52

By the end of the colonial era, Senegal was home to only a handful of cantons that still resembled the provinces of precolonial states. Most colonial units had been dramatically altered by decisions both large and small.Footnote 53 That few canton chiefs ruled over meaningful territorial divisions reflected the fact that precolonial polities had effectively “been incorporated into the French bureaucratic state” by the onset of the First World War. By 1935, the colonial state had abandoned any formal demand that the canton corresponds to indigenous history, defining it simply as “a group of villages and the territories that depend on them.”Footnote 54 The result of this nearly constant tinkering with administrative borders was that the canton “ceased to have, in effect, an ethnolinguistic or historical base necessary to be more than a simple territorial subdivision.”Footnote 55

Efforts to map these changes are stymied by the imprecision of French colonial maps or, more accurately, their nonexistence before the 1920s. Such ambitions are further impeded by the fact that the French had at best an approximate idea of where many villages were physically located in early decades, meaning they were inconsistently allocated to the correct colonial canton in early censuses. One way to estimate the degree of change is to engage in a simpler endeavor of counting the frequency of changes to subnational units. To do so, I turn to the Journal Officiel du Senegal, which recorded all administrative changes in the colony. Figure 3.1 displays the frequency of territorial changes to canton borders within each cercle over time. Note that cercles, grouped by colonial regions on the right-hand y-axis, themselves come in and out of existence during this period. The figure demonstrates that all cercles and regions saw redistricting at least once. Changes to canton borders were particularly prominent in the 1920s and some regions, such as Dagana, witnessed numerous changes while others, such as Bakel or the Petite-Cote, home to Dakar, remained more consistent.Footnote 56 There is no apparent correlation between the frequency of changes and a cercle having had most of its territory dominated by a precolonial state.Footnote 57 By the late colonial era, administrative units were largely settled.

Figure 3.1 Colonial changes to cantons by cercle and region, 1895–1960

Delimiting the Postcolonial State

Following independence in 1960, the postcolonial Senegalese state took its own turn at restructuring the state as a vehicle to promote state-led development, turning cantons into arrondissements and, in 1964, creating departments, similar in size to colonial cercles, nested in regions.Footnote 58 Though a few arrondissements persisted untouched, many aggregated two or three colonial cantons. Alternatively, others split existing cantons to create new administrative units altogether. On average, cantons were split into 2.5 arrondissements and, in turn, today’s average arrondissement includes territory from three to four cantons.Footnote 59 Like their colonial predecessors, the postcolonial state sought to balance the population across arrondissements and to generate economic complementarities by creating administrative units based around central economic infrastructure.Footnote 60 The cost of this strategy was significant variability in surface area and population density across administrative units. This eliminated “any fiction of a territory based on historical tradition,” and, accordingly, the state renamed all administrative units after their chef-lieu, or capital city or village, to signal this break.Footnote 61

Numerous changes took place in the first years of independence. At times, they were practical, such as the decision to move the capital of Adeane arrondissement to the village of Niaguis after Adeane-village was deemed too remote. Similarly, a new arrondissement was created in Bakel because citizens were traveling to neighboring Mali for social services rather than the more distant headquarters of their arrondissement.Footnote 62 At others, they were political. As the postcolonial regime sought to consolidate a reliable political foundation in the countryside, they proved willing to negotiate with key vote brokers, notably Sufi religious leaders.Footnote 63 The state redrew the border between Thienaba and Pout arrondissements in this vein, moving a handful of villages to the former, for example, to improve the villagers’ access to their marabout, a resident of Thienaba-village.Footnote 64

Decentralization brought the need to further divide the country. This process is crucial to subsequent outcomes of such reforms. To the extent that local elites – who seek to distribute goods to their own villages or clients as a means to reinforce their social status – strive to capture local policymaking as I have argued, the dynamics of which villages comprise the local government is central to understanding local redistributive politics. If local elites could coordinate around the delineation of their local governments, it is possible that something about their relative ability to do so drives the outcome variables under study here. When local government boundaries are created via a bottom-up, consultative process, such was the case during Mali’s decentralization reforms, then contemporary government performance could be the product of the capacity of some communities to organize and demand their own local government.

As stated in the 1972 law introducing decentralization (article 1 of law 72–75 Relative aux Communautes Rurales), a local government, or rural community, would be “a number of villages belonging to the same territory, united by a solidarity resulting from their neighborship, having common interests and able to find the resources necessary for their development.” The degree to which these ideas of solidarity and neighborliness came into play is questionable, however. To the extent that the 1972 decentralization reform was designed to meet the central state’s political objectives, the boundaries established by the 1972 reform by and large left the previously lowest level administrative unit, the arrondissement, intact, simply dividing it into three to four local governments.Footnote 65 Rather than seeking out meaningful political entities, the state stuck to eminently rationalist strategies, crafting an administrative structure that divided each region into three departments, each department into three arrondissements – themselves the product of a late colonial bureaucratic desire for uniform administrative divisions – and each arrondissement into three local governments. Local governments were created according to a “principle of centrality” as the government employed technical criteria to identify villages that served as economic poles, such as weekly markets, peasant cooperatives, or health centers, for local government capitals.Footnote 66 Over half of the villages identified as local economic poles in response to a 1962 government request for the name of influential villages in Senegal Oriental (contemporary Tambacounda and Kedougou regions) are either urban communes or local governments capitals today, for instance.Footnote 67

Beyond this, the government was concerned with ensuring demographic balance and, more ambiguously, “economic potential.”Footnote 68 The stated goal of having 5,000 inhabitants as a minimum threshold for economic viability led to exceedingly large territorial units in areas of the country with low population density. The government did commission a series of studies undertaken by the Direction de l’aménagement du territoire (DAT) to identify potential ways to divide the country into viable socioeconomic units. These included sociological criteria, though these rarely won out in the end.Footnote 69 In Koungheul, DAT technicians faced low population densities that problematized their ability to create “economically viable” units, conceptualized thinly as a locality’s ability to raise sufficient revenues from the rural tax, without risking under-administration and weakened popular participation. The DAT proposed two solutions: they could firstly delimit local governments around potential “villages-centres,” those with the historical importance, population, proximity to infrastructure, and transport. This would create local governments where every village would be within 15 kilometers of a center, but it relied on the hope that future population growth would make the units economically viable. Alternatively, they could delimit six local governments that were much larger and more diverse, but able to muster sufficient tax revenue in the present. The latter option won the day.Footnote 70

Thus, while the central state aspired to create administrative units composed of villages that shared attributes like neighborly solidarity, this goal had to be reconciled with other, more tangible objectives, such as grouping villages that together would have “the resources necessary for their development.”Footnote 71 Despite paying lip service to the value of consulting with local populations, in many cases, the state simply delimited local governments solely by rational “demographic criteria or on the number of villages grouped together, without any meaningful historical or socioeconomic reference,” or to the lived dimensions of territory.Footnote 72

There is little evidence that local political cleavages systematically influenced boundaries delimitation.Footnote 73 Writing on Kolda Region, Fanchette (Reference Fanchette2011, 234–235) notes that local governments lack “any historical legitimacy,” resulting in rural communities that are “too large, heterogeneous and traversed by multiple political conflicts.” In many areas, local government boundaries are seen as inimical to development. This generated complaints from central state officials assigned to rural areas, such as one adjoint subprefect who noted bitterly that government functionaries in Dakar had simply devised boundaries they thought would meet the state’s political needs at the cost of local considerations. “The populations do not question the boundaries because the administration made them,” he sighed.Footnote 74 Faced with endemic political divisions induced by local government boundaries, “democracy can do nothing” in many communities, surmised one technical advisor in Dakar.Footnote 75

Still, this is not always the case. One village chief in Louga Region described his local government as a “homogenous and solidary unity,” echoing almost directly the language of early planners. In this case, the local government boundaries reflected one-half of a colonial canton that had been split into two.Footnote 76 At the other extreme however, the delimitation of decentralized political units has been “explosive” as villages with long histories of rivalrous relations find themselves within the same local government. This has repeatedly resulted in weakened local government institutions beset by in-fighting as local factions gained a new and influential venue within which to adjudicate longstanding disputes.Footnote 77

More recently, Senegal undertook significant administrative redistricting in 2009, creating fifty new local governments, and in 2011–2012, thirteen more. This leads to a total of 384 local governments at the time of research with the addition of 126 urban communes (including Dakar’s urban communes). Numerous explanations have been put forward for these changes. The government claimed it was trying to bring the administration closer to the citizenry by creating smaller administrative units, but the general consensus is that the regime of President Wade was acting with a direct eye on the 2009 local elections. In reality, local governments that were divided had, on average, more villages (76 versus 56) and larger surface areas (110,437 hectares versus 58,784). Historically, acephalous areas were more likely to have an administrative division, with 33 percent of local governments seeing some boundary change compared to only 16 percent in formerly centralized regions (significant at p < 0.001).

It is not a secret that these changes were driven by the political motives of the central state. A government bureaucrat at the Direction des Collectivites Locales laughed when I asked about new commune creation, pulling out a file full of such requests. Most would go nowhere, he argued, because they were so clearly political – written by members of the opposition or disgruntled villages’ chiefs – even if petitioners framed them in terms of local development. Still, a few that were more serious would be sent to the Ministry of the Interior for review though the outcome was often contingent on central government preferences.Footnote 78 This claim is supported by the story one mayor shared of having written to the Minister of Local Authorities in the mid-2000s to petition for a division of his local government, which covered a vast expanse that made it difficult to serve the nearly 100 villages within its boundaries. He was shocked, he recounted, when a presidential décret arrived at his desk with a list delineating which villages would stay in his local government and which would be removed to form a new collectivity. “I thought they would come and consult with the population,” he mused, but instead the whole process was “antidemocratic,” resulting in villages only a few kilometers from his local government’s capital being attached to the new local government, whose own seat was nearly 10 kilometers to the south.Footnote 79 Indeed, numerous individuals working in rural areas noted the sloppiness with which recent divisions had been conducted in Dakar. In one community in southeastern Senegal, a village was officially listed as belonging to a neighboring local government even though it was more than 10 kilometers from the border. This meant that citizens of the village had to travel to their “official” local government for all paperwork for over a year while the local administration attempted to remedy the situation.Footnote 80

Looking across archival documents, secondary literature, and interviews, I find scant evidence that areas home to precolonial states were routinely able to self-constitute their local governments. Though boundaries are rarely, if ever, plausibly as-if random, we can be more or less confident that they are not endogenous to the processes under study. The delimitation of subnational boundaries throughout the colonial and postcolonial eras prioritized the practical and political ambitions of the central government and I find no evidence of a systematic relationship between the ability of elites to influence the process of local government boundary delineation and precolonial political geography in archival and interview data.

Conclusion

This chapter made two historical claims that build on the introduction to Senegal’s dynamic precolonial political geography offered in Chapter 2. The decentralization reforms introduced in 1996 dramatically altered the nature of local public goods delivery at the same time that it introduced new incentives and rewards for politicians. These reforms intersected with the divergent grassroots legacies of precolonial statehood to structure distinct cross-village redistributive dilemmas across the country. It is precisely because democratic decentralization opens up the possibility that local elected officials will draw from a number of villages, that local decision-makers are obliged to negotiate across villages when deciding how to distribute scarce projects and resources.

This also reveals the importance of my final historical claim: how did any given local government come to be comprised of the villages that constitute it? By tracing the history of subnational boundary creation from the colonial period to the present with a range of archival and interview data, I mitigate the concern that local government boundaries are endogenous to local social networks. In contrast, redistricting was repeatedly undertaken with an eye to the multitude of changing objectives of colonial and postcolonial states. This raises an important reminder that space is not neutral, and we should not assume that the boundaries we reflexively use are necessarily exogenous to the processes we study.

It was only with the 1996 decentralization reforms, therefore, that social legacies of Senegal’s precolonial past interacted with the bounds of decision-making, facilitating institutional congruence in some communities and incongruence in others. I map out these diverging political dynamics in the next chapter.