Protests since 2016 in Chile against the expected low pensions of the private pension system (Bugueño and Mallet 2019), in Argentina in response to government attempts to introduce changes to the indexation of pensions (La Nación 2017), and recent developments in Peru and Uruguay (El País 2020), among other countries, signal that pension policy is high on the public policy agenda in Latin America.

Pension reform is not new to the region though: in the 1980s and 1990s, Latin America was at the forefront of pension privatization, a process entailing the full or partial replacement of preexisting pay-as-you-go (PAYG) public pension systems with ones based on individual private pension accounts (Orenstein Reference Orenstein2008). Yet recent years have witnessed the rise of an opposite trend: that of re-reforms that have increased the role of the state in pension provision. The latter has varied from the elimination of the private pillar to the maintenance of the private pillar (albeit reformed) and the rebuilding of a previously small first public pillar of contributory and noncontributory pensions.

Comparative analyses of the factors that explain these variations are still in short supply, although they have provided useful analytical insights for further research (Pribble Reference Pribble2013; Borzutzky Reference Borzutzky2019; Castiglioni Reference Castiglioni2018; Busquets and Pose 2016; Baba Reference Baba2015). The emerging insight from recent works is that although in the 1990s analysts believed that the state would “retire” from pension provision (Madrid Reference Madrid2003), recent re-reforms seem to suggest that the state “is back” (Rulli 2014). Yet scholars still need to understand more about the factors that play a role in shaping re-reform outcomes.

We contend that analyzing the factors that shape pension re-reforms can provide valuable insights to the literature on legacies and institutions in social policy change (Weaver Reference Weaver2010; Pribble Reference Pribble2013; Niedzwiecki and Pribble 2017; Borzutzky 2019), as well as contribute to the broader comparative literature on public policy change in the region and beyond (Béland and Powell Reference Béland and Martin2016; Pierson Reference Pierson2001). More widely, evidence shows that, variations notwithstanding, pension systems across the region are still far from providing adequate pensions that cover large parts of the population (Rofman and Olivieri Reference Rofman and María2012; Arenas de Mesa Reference Arenas de Mesa2019). Furthermore, the COVID-19 pandemic has sparked a debate on allowing access to private pension reserves as a way to provide some relief to affected workers (Americas Quarterly 2020). As the adequacy of pensions remains a concern and the role of private pensions continues to be challenged, we expect pension re-reform to remain high in the policy agenda in upcoming years. We therefore contend that understanding the factors that shape re-reforms may be useful for scholars and practitioners interested in pension and public policy issues.

We focus on the cases of Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile since the mid-2000s. From a comparative perspective, these countries share some common characteristics: they are all in the same region, and all of them introduced a mandatory pillar of private pension accounts in the 1980s and 1990s, notwithstanding some variations in terms of the degree of privatization chosen. While Chile (1981) and Bolivia (1997) opted for full privatization through substitutive reforms, Argentina (1994) chose a mixed model comprising a reformed public pillar and a second pillar, on which workers had a choice to contribute either to a public tier or to a private one. However, the three countries’ re-reforms since 2005, while increasing the role of the state in pension provision, have varied. Argentina eliminated the private pillar and switched back to the public one for all workers in 2008. Bolivia implemented Renta Dignidad in 2007 as a noncontributory pension that considerably increased coverage and benefits financed by the public sector and legislated to eliminate private pension administrators in 2010, but maintained private pension accounts under a new public administrator. Meanwhile, Chile in 2008, in addition to strengthening some aspects of the private pillar, introduced measures to strengthen noncontributory state pensions.

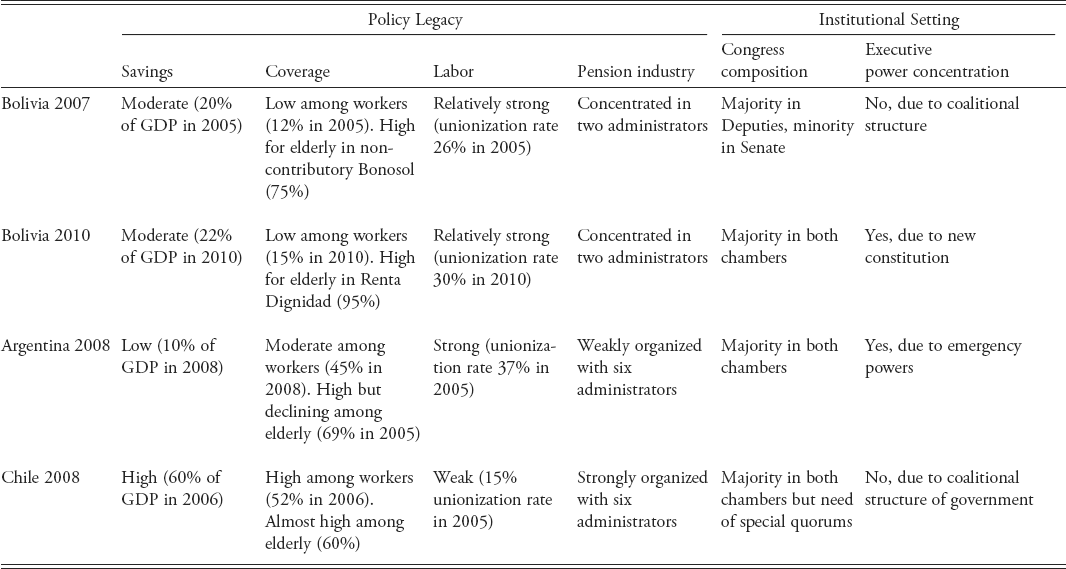

To explain re-reform variation, this study focuses on the legacy generated by previous reforms and the domestic institutional setting. We theorize that where a weak legacy, characterized by low coverage and savings rates, a weakly organized pension industry, and strong societal groups that oppose the private system, combines with a strong institutional setting, characterized by a government with large support in Congress and high levels of power concentration in the executive, re-reform outcomes may lead to the outright elimination of the private pillar or at least a significant reconfiguration of its administration. Conversely, where a strong legacy of previous reforms combines with a weak institutional setting, re-reform outcomes will tend to maintain the private pillar and possibly expand the role of the public one.

The article proceeds to discuss the main theories of pension reform and present the theoretical framework. Then it presents the trajectories of re-reforms in the countries under study, and finally discusses the comparative insights of the analysis and extends the discussion to recent developments in these cases and beyond.

Varieties of Pension Reforms and Re-reforms

Scholars analyzing the second wave of pension reforms in Latin America since the mid-2000s have readapted some of the arguments put forward to analyze the first wave of reforms (Brooks Reference Brooks2005; Orenstein Reference Orenstein2008; Pribble Reference Pribble2013; Weyland Reference Weyland2005; Kay Reference Kay1999) and complemented them with new approaches. Building on the concept of policy feedback (Pierson Reference Pierson2001), scholars have argued that policies may also produce negative feedback, which undermines them and ultimately leads to changing them (Weaver Reference Weaver2010; Jacobs and Weaver Reference Jacobs and Kent2015). For example, Arza (Reference Arza2012) shows how the low levels of support for the private pension system in Argentina in the aftermath of the 2001 crisis and the low levels of coverage and savings provided support for its elimination in 2008. Similarly, Borzutzky (Reference Borzutzky2019), focusing on Chile, argues that negative policy legacies, in terms of low expected future pensions, played a significant role in the 2008 re-reform.

Policy legacies can be interpreted in broader terms to refer to the legal structure set out by a given policy and the types of actors it generates (Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011). In this sense, scholars have highlighted the role in re-reforms of veto actors, such as trade unions and social movements (Castiglioni 2018; Pribble Reference Pribble2013; Niedzwiecki Reference Niedzwiecki2014). For example, Borzutzky (Reference Borzutzky2019) stresses the role of the emerging No + AFP (No more AFP) movement in Chile since about 2016. Actors generated by previous reforms may also play a role, as illustrated by how the powerful pension industry in Chile outmaneuvered and resisted re-reform attempts affecting the private pillar (Bril-Mascarenhas and Maillet Reference Bril-Mascarenhas and Antoine2019; Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011).

Baba (Reference Baba2015) provides a broader comparative framework of re-reforms in the region, highlighting that they range from those that increase the role of the state in pension provision (swingback reforms) to those that deepen the role of the private pillar. Focusing also on the role of policy legacies, Baba argues that the type of compromise among policymakers and veto actors in the first generation of pension reforms, and the nature of the pension policymaking process, condition the type of re-reforms ultimately pursued.

Analyses in central and eastern European countries have also shown that the legacy of the previous reforms may offer hints to understand the variety of re-reform outcomes. Sokhey (Reference Sokhey2017) argues that re-reforms that eliminate the private pillar are more likely in countries where privatization has been moderate. This is because the savings in the private pillar may be significant but, given the moderate reform, veto actors, such as private pension administrators and experts, are not well organized. In these countries, sweeping re-reforms that reduce or eliminate the private pillar may be more likely when governments face significant fiscal pressures, as witnessed in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis.

The role of policy legacies in pension reform notwithstanding, the role of political institutions cannot be disregarded. Analyses have highlighted that governments with large majorities have been able to pass significant re-reforms eliminating or significantly altering the role of the private system in pension provision, as in Argentina and Bolivia (Arza Reference Arza2012; Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2014). Some analysts have also argued that the level of concentration of power in the executive (the extent to which the president can take decisions without consulting members of the cabinet or coalition) has impacted pension and social policy reform in both reform waves (Castiglioni Reference Castiglioni2018; Castiglioni Reference Castiglioni2010; Valdés-Prieto Reference Valdés-Prieto2009, 26).

In sum, the emerging literature seems to agree that the legacy of previous reforms regarding the performance of the private pillar and the relevance of societal veto actors that participated in previous reforms or were generated by those reforms should be taken into consideration. Yet the domestic institutional setting also seems to affect the final content of re-reforms.

We theorize that the interaction of policy legacies of first-wave reforms with the domestic institutional setting is central to understand re-reform outcomes. Legacies from previous reforms can be either weak, given by low coverage and saving rates, a weakly organized pension industry, and strong societal actors that oppose the system; or strong, given by high coverage and savings levels, a strong pension industry, and relatively weak societal actors that oppose the system. Regarding the institutional setting, this, too, can be either weak, where the executive does not enjoy a large majority in Congress and does not significantly concentrate powers in the president’s hands, or strong, characterized by a president with a large majority in Congress and a high level of power concentration compared to other ministries. The full range of possible re-reform outcomes resulting from our theoretical expectations is laid out in table 1.

Table 1. Theoretical Expectations for Re-Reform Outcomes

Re-reforms in the upper two quadrants of the table are likely to change the structure of at least one of the pillars, given the low legacy. Governments operating in a strong institutional setting are likely to go all the way to an outright elimination or significant change of the private pillar; meanwhile, those operating in a weak institutional setting will focus on introducing significant changes to the first public pillar. By contrast, governments facing a strong legacy and operating in a weak institutional setting will need to negotiate the re-reform outcomes, and as a result, the private pillar will be largely untouched. We do not expect re-reforms in a situation of strong legacy and a strong institutional setting as the case for re-reform is not evident, given the strong system already in place and the government strong enough to rebuff any proposals.

We analyze re-reforms in Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile since the mid-2000s to illustrate how they fit our theoretical expectations. These regional neighbors all introduced a private pillar of individual pension accounts in the 1980s and 1990s, but their pension re-reform outcomes have varied. Chile in 2008 left the private pillar largely untouched and developed noncontributory first-pillar pensions. Argentina in 2008 eliminated the private pillar. Bolivia expanded first-pillar noncontributory pensions in 2007 and then, in 2010, decided to maintain private accounts in the second pillar, albeit under state management. The 2008 Uruguayan re-reform could also be considered for this comparison, given Uruguay’s similar economic development to that of Argentina and Chile and the fact that the three of them were pioneers in the development of a pension system. The re-reform of 2008 maintained the private pillar, albeit with some regulatory changes, while it improved eligibility criteria for the first pillar by reducing the number of years necessary to obtain a pension (Busquets and Pose Reference Busquets and Nicolás2016). Since this outcome is similar to that of Chile in 2008, we argue that the addition of this case would not improve variation in our model.

As the cases of Chile and Bolivia show, re-reforms that expand the role of the state in pension provision may change the architecture of the retirement system through the introduction of new, noncontributory public pensions. Similarly, we contend that re-reforms are not limited to changes entailing the elimination or reduction of contributions to the private pillar, as in Argentina and Eastern Europe (Arza Reference Arza2012; Sokhey Reference Sokhey2017). Therefore, we understand re-reforms as changes in the overall architecture of the system (Hinrichs and Kangas Reference Hinrichs and Ollie2003), in which components of future retirement income are altered altogether. Specifically, re-reforms understood in this way include changes in the balance of the private and public pillars in the overall architecture of the pension system. This definition is more encompassing than just focusing on the elimination or reduction of contributions to the private pillar.

Our main indicators of legacies are pension system savings and coverage (Pribble Reference Pribble2013). Regarding coverage, two common indicators are the percentage of members of the economically active population making pension contributions and the percentage of people age 65 and older who receive a pension. Rofman and Olivieri (Reference Rofman and María2012) and Arenas de Mesa (Reference Arenas de Mesa2019) found that the average coverage ratio of the economically active population in Latin America was about 40 percent in the mid- 2000s, right before the re-reforms analyzed in this study took place. We argue that a coverage ratio of above 50 percent denotes a high coverage for workers, while rates below 20 percent represent low coverage.

For pensioner coverage, the above studies found that the average coverage for the elderly from both the contributory and noncontributory pillars was about 55 percent in the mid-2000s. We therefore argue that rates above 65 percent denote high pensioner coverage, while rates below 20 percent denote low. Regarding the level of savings in the private pillar, Ortiz et al. (Reference Ortiz, Valverde, Urban and Wodsak2018) found, in their study of 24 countries that introduced privatization, that the average amount of assets under management was about 14 percent of GDP between 2000 and 2016. Based on this figure, and again considering the relatively high levels of informality in the region, we can assume that levels above 30 percent of GDP denote a high level of savings, while levels of about 10 percent or less are low. For the role of unions and the pension industry, we use different quantitative and qualitative sources. Regarding the institutional setting, we consider the number of legislators from the government’s party or coalition in Congress, and we rely on secondary sources to ascertain whether the president can concentrate power.

In terms of the interaction of other factors, such as the country’s fiscal situation and the impact of economic crises, we argue that these can accentuate the case for re-reform but they do not actually shape it. This is, for example, the case of Argentina, where the 2008 economic crisis accentuated further the fiscal stress, yet this acted more as an additional pressure than as a key factor in determining reform outcome (Baba Reference Baba2015, 1853). Furthermore, the implementation of reforms in Chile before the onset of the 2008 financial crisis provides additional support to our argument about the importance of policy legacies and the institutional setting in comparison to the economic argument.

Observers could also point to economic and demographic variation as leading to diverging re-reform outcomes. Chile and Argentina have similar levels of economic development and a more rapidly ageing population than Bolivia, which is also poorer. All things being equal, we would expect a poorer country to focus on noncontributory pensions exclusively to provide a basic income for all and rapidly to increase pensioner coverage (Arenas de Mesa Reference Arenas de Mesa2019). Meanwhile, wealthier countries and countries with a larger ageing population are expected to maintain or even expand the role of private pensions so as to relieve pressure on state finances (Béland Reference Béland2019). While the introduction of Renta Dignidad in Bolivia goes in the direction of expanding noncontributory pensions, the 2010 re-reform maintained individual pension accounts. Chile in 2008 expanded the role of noncontributory pensions. In addition, while Chile maintained the private pillar, Argentina eliminated it. We conclude that the level of economic development and population ageing does not seem to have a distinctive effect on re-reform outcomes.

Although previous studies have considered the role of ideology in the first wave of pension reforms (Castiglioni Reference Castiglioni2018), we do not expect ideology to play a significant role in re-reform cases. Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia had left-of-center governments when re-reforms where passed in the period under study, yet re-reform outcomes have varied significantly. This suggests that the locus of variation may be due to legacies and the institutional setting. This is consistent with the observation of some scholars that variation among left governments in the region in the early 2000s was due to historical and institutional features in each country (Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011, 13).

We also argue that international and transnational actors have not played as significant a role as during the first wave of reforms in the 1990s. The World Bank and the International Labor Organization (ILO) have been largely absent in the rereform processes that have taken place in the region. While it is true that in 2008 the Bolivian government consulted with the ILO on reform options, the government rebuffed the ILO’s recommendation of expanding the mixed system (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2018, 127). These organizations’ lack of influence may be related to the processes that have taken place inside these organizations since the early 2000s, when the former recommendation of pension privatization as a “one size fits all” model has been questioned in comparison to designs that are sustainable, extend coverage, and provide a social protection floors (Heneghan and Orenstein Reference Heneghan and Mitchell2019).

Varieties of Re-reforms in Three Latin American Countries

The history of pension reforms in Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile since the mid-2000s demonstrates the variation in legacies, development, and subsequent outcomes in each country.

Argentina

The Argentine pension reform of 1994 retained (albeit reformed) the first public pillar, providing a basic pension to all workers. The second pillar comprised two tiers, a first public PAYG tier and a second tier of private individual accounts managed by pension fund administrators (Administradoras de Fondos de Jubilaciones y Pensiones, AFJPs). At the time the reform was enacted, existing workers and new entrants were given the choice of contributing either to the public or the private tier. Those who did not express a choice were automatically assigned to the AFJP, which was managed by the state-owned Banco de la Nación. Once in the AFJP, workers could not switch back to the public-run tier.

The 1994 reform was highly contested by opposition parties and the labor movement and was approved only following concessions to labor, such as the introduction of the public tier in the second pillar and the permission for unions to run their own AFJPs (Brooks Reference Brooks2009; Madrid Reference Madrid2003). But the labor movement and other political and societal actors remained fierce critics of the new private AFJP system nonetheless (Bour Reference Bour2006).

Labor leaders’ opposition to the private system strengthened further in the aftermath of the 2001—2 economic crisis (Datz and Dancsi Reference Datz and Katalin2013). Moreover, the labor movement remained a relatively strong actor. This strength is explained by legislation enacted since the 1940s which, among other things, recognizes the union with the most members as the only one that can negotiate wages and other conditions and has allowed unions to contract with their own health care providers, to which workers are required to subscribe (Law 23551; Murillo Reference Murillo2005, 197). The strength of labor is illustrated by the fact that by about 2005, about 37 percent of workers were members of a union, the highest percentage in Latin America (ILO 2020). Against this background, the center-left governments of Néstor Kirchner (2003—8) and Cristina Fernández de Kirchner (2007—15) implemented a series of economic interventionist policies, such as the nationalization of utility companies, which increased the labor movement’s power even more (Alonso and Di Costa Reference Alonso and Valeria2015, 38).

The limited role of the private tier led to a low level of savings accumulated in the private system, reaching about 10 percent of GDP by 2008 (Ortiz et al. Reference Ortiz, Valverde, Urban and Wodsak2018). In this context, AFJPs did not become a key veto actor in the post-1994 period. This weakness was also related to the fact that most AFJPs were owned by large banks, whose focus and source of revenue was not the administration of pension funds themselves but other core banking activities (Hujo and Rulli Reference Hujo and Mariana2014). Furthermore, the one body that defended the interests of AFJP firms, the Unión de AFJP, was weakly organized (Hujo and Rulli Reference Hujo and Mariana2014).

Member coverage remained rather low: while about 45 percent of members of the economically active population were contributing to the pension system in 1994, this fell to 37 percent in 2003, increasing to 45 percent again in 2008 (Rofman and Olivieri Reference Rofman and María2012, 41). By the early 2000s, most workers affiliated with the private tier had an insufficient level of savings in their private accounts and an insufficient number of contribution years to qualify for a full pension from the public pillar. Coverage among the elderly was high but declined from 77 percent in 1994 to 69 percent in 2005 (Rofman and Olivieri Reference Rofman and María2012, 41). In this context, public support for the private system diminished over time. Indicatively, a 2008 survey showed that 90 percent of respondents believed that pensions should be primarily in the hands of the state (Arza Reference Arza2012, 56). In sum, the 1994 reform led to a legacy of low savings, rather low levels of coverage among workers but higher among the elderly, a weak pension industry, and a strong labor movement opposing the private system.

Re-reform measures started in 2005 with the introduction of a “moratorium” law that allowed a temporary flexibility in contributory requirements for obtaining a pension (Hujo and Rulli Reference Hujo and Mariana2014, 12). This was followed by a law in 2006 that allowed members of the private tier to switch back to the public one. The process culminated with the reform presented in October 2008 to eliminate the private tier and switch funds and members to the public pillar. The labor movement openly supported the government’s reform (Perfil 2008). Meanwhile, the weakness of the pension industry in the reform process was illustrated when the president of the Union of AFJP learned about the 2008 reform only from the press, and his complaints were not taken seriously (La Política Online 2008).

Surely, the lack of access to international markets, following the incomplete restructuring of government debt in 2005 and the impact of the 2007—8 crisis, made the nationalization of the private tier a palatable option for the government to secure badly needed funding (Datz and Danesi 2013). Nevertheless, the political institutional setting proved key to passing these reforms. President Néstor Kirchner’s party, the Frente para la Victoria (FPV), enjoyed a sizable majority in both chambers of Congress up to 2007. On being elected in late 2007, Cristina Fernández de Kirchner maintained that comfortable majority. In the Chamber of Deputies, the FPV had 129 deputies out of 257, with about 15 more from allies and provincial parties who consistently voted with the FPV. In the Senate, the FPV had 42 out of 72 seats (Secretaría Parlamentaria 2020). Furthermore, as her husband had, Fernández de Kirchner maintained a high level of power concentration via, for example, using emergency powers delegated by Congress and discreet budget allocations (Levitsky and Murillo Reference Levitsky and Murillo2008, 80). Thus, she drafted the re-reform nationalization bill exclusively with the support of the secretary of the National Social Security Administration (ANSES) and without any internal resistance (La Política Online 2008). The government presented the bill in early October 2008, and both chambers swiftly passed it by the end of that month.

However, the speed of the re-reform meant that the future sustainability of the system was not properly assessed. Some estimates showed that the new system could experience a deficit of between 1.7 and 4.1 percent of GDP by 2030, reaching over 5 percent by 2050 (Bridger and Cado Reference Bridger and Osvaldo2008, 12). A further change in 2009 to the indexation formula, based on an index composed by the change in wages and contributions of the public pension system, resulted in a yearly increase well above inflation (El Cronista 2017). In this context, total pension expenditure was estimated to reach 15 percent of GDP in 2050 (Rofman and Apella 2016, 115). On the other hand, coverage increased significantly, rising to 90 percent of the elderly population by 2011, mainly due to the “moratorium” (Rofman and Olivieri Reference Rofman and María2012). The policy legacy of increasing pension spending, due largely to the significant expansion in coverage that culminated with the 2008 nationalization of private pension funds, may exert pressure for future reform.

Bolivia

The pension reform implemented in 1997 eliminated the old, state-run PAYG public pillar, and all workers were forced to join the new system of private accounts. A noncontributory pillar, Bonosol, was also introduced for those aged 65 and over who met certain eligibility criteria. The benefit was funded out of the dividends of state-owned shares of privatized companies.

A significant problem for the new private system was the large informal sector, composed mainly of independent workers (about 58 percent of the economically active population, EAP), which left only a minority of urban workers contributing systematically. By 2005, member coverage was the lowest in Latin America, at around 12 percent of the EAP (Picado Chacón and Durán Valverde Reference Picado and Gustavo2009, 100; Arenas de Mesa Reference Arenas de Mesa2019, 149). Coverage among the elderly from the contributory private system was just 4.7 percent in 2005. Coverage of the noncontributory Bonosol among the elderly was high, at around 75 percent, yet this was a low benefit of about 248 USD (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2014).

The new system was dominated by two private pension administrators (Administradoras de Fondos de Pensiones, AFPs) and, given its mandatory feature, it managed to accumulate a moderate level of savings, over 22 percent of GDP by 2010 (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2014, 10). Low coverage and low density of contributions, which would lead to low future payments, was perceived as a problem, ultimately resulting in low support for the private system. In a perception survey conducted in 2008, only 38 percent of respondents wanted to keep the private system, while 61 percent were in favor of a new system (Arze Vargas 2008).

The legacy of moderate levels of savings, together with the concentration of the industry in only two AFPs, meant that the concerns and issues raised by AFPs during the reform process could not be totally ignored. The main labor confederation (Confederación Obrera Boliviana, COB) had been an ardent opponent of the private system since the passage of the 1997 reform. After 2006, it played a key role in discussing with the government future changes to the system and became a significant veto player in the reform process (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2018, 9). While the labor movement in Bolivia may not be as strong as in Argentina, in the mid-2000s, the overall unionization rate was still significant, about 26 percent (ILO 2020). Furthermore, membership in unions belonging to some key sectors of the economy, such as the mining and oil industries, was quite significant, eventually leading many of the demonstrations against changes to the pension system in subsequent years.

The new left-leaning, movement-led administration of Evo Morales took over in 2006, and it focused on introducing significant labor and social policy changes, which had been important promises during the presidential campaign. The institutional setting Morales faced was marked by the way his party, the Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS), reached power. MAS was a new left-leaning and power-dispersed movement that amalgamated a range of grassroots movements representing, inter alia, coca-producing farmers, peasants, and indigenous groups (Levitsky and Roberts Reference Levitsky and Roberts2011, 13). While heterogeneous, they were all disenchanted with neoliberalism and the political class and had led some significant protests in the early 2000s (Mainwaring et al. Reference Mainwaring, Bejarano and Leongómez2006). MAS had a majority in the Chamber of Deputies but was in the minority in the Senate. To further strengthen his administration, Morales had to negotiate cabinet positions with some organizations that had not originally supported him (Zuazo Oblitas Reference Zuazo Oblitas2008). This, in turn, meant that some of the groups that had supported MAS would not hesitate to mobilize when considering that their specific demands were not being heard. Thus, unlike in Argentina, presidential authority was more dispersed than concentrated.

The negotiation leading to the introduction of Renta Dignidad in 2007 illustrates how policy legacies and the characteristics of the institutional setting influenced the process. The low amount of Bonosol meant that the grassroots movements supported the higher Renta Dignidad. Yet the COB opposed the program, concerned about its funding, seeing it as just a charity, and arguing that the focus should be on the reform of the private pillar (Anria and Niedzwiecki Reference Anria2016, 23). In Congress, the Senate initially rejected the bill. However, after the Chamber of Deputies insisted on the original version of the bill, mass demonstrations by grassroots movements took place. On the day the Senate was due to vote on the bill, protesters prevented opposition senators from entering the building, and MAS senators passed the bill (Anria and Niedzwiecki Reference Anria2016, 25). Even after introducing the Renta Dignidad, however, the government’s key concern remained the private system. Therefore it continued to work on a reform project, an effort that had already started in early 2007 with the key input from the COB (ANF 2007).

While the policy legacy of a system with low member coverage and low public support may explain why the government saw the reform of the private system as the next step, the political institutional setting is key to understanding why the reform went ahead only in 2010. The passage of Renta Dignidad showed that in a context in which presidential authority was not concentrated, support in Congress was key. In 2006, the government called a Constitutional Assembly with the purpose of approving a new constitution. The new constitution was approved in a referendum in January 2009 by over 60 percent of the voters, and which expanded the power of the president (Anria Reference Anria2016, 105). New presidential and congressional elections took place later that year, resulting in the re-election of Morales and a two-thirds majority for MAS in both chambers of Congress: the MAS obtained 88 out of 130 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 26 out of 36 seats in the Senate (OEP 2009).

The government then started working on a new pension reform. It focused on improving benefit adequacy by increasing the noncontributory Renta Dignidad and introducing a new first-pillar contributory pension, Pensión Solidaria. Early versions of this proposal were shared with the COB, yet leaders initially opposed the reform because they saw the level of the proposed contributory pension insufficient (El País 2013). Furthermore, some COB members criticized the maintenance of the individualistic nature of the system, since the private individual accounts would continue to exist (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2018, 128).

Negotiations with the COB practically stalled at the beginning of 2010. This coincided with the first strike convoked by the COB against Morales, demanding wage increases but also opposing the re-reform bill (El Diario 2010a). Facing significant demonstrations, the government ultimately made some concessions to the COB, such as reducing the retirement age from 65 to 60 (58 for the powerful mining sector workers) and improving the amount of Pensión Solidaria (El Diario 2010b). The reform bill was swiftly passed by two-thirds of the Congress, thanks to the government’s large majority (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2018). Critically, the individual private pension accounts were maintained but managed by a state-run administrator (Gestora Pública de la Seguridad Social).

Yet the government could not totally ignore the concerns of pension administrators, and while it initially offered to buy the AFPs’ assets, it later withdrew the offer over concerns that the new public administrator would inherit judicial claims for unpaid contributions that had to be recovered (Mesa-Lago Reference Mesa-Lago2018, 11). While the overall policy legacy of the system was weak, compared to those in Argentina, the AFPs in Bolivia were in a stronger position, given that the market was concentrated in just two administrators; and while coverage was low, savings still represented about 22 percent of GDP. Thus, AFPs agreed with the government on a “transition” to transfer the administration of the individual accounts to the new public entity. In exchange for recovering unpaid contributions and transferring members’ data to the new state-run administrator, the government agreed to compensate the owners of the two AFPs (Los Tiempos 2018).

This transition is still ongoing, and constitutes the most striking legacy of the reform, since the government has postponed several times the start of operations of the Gestora Pública de la Seguridad Social (Los Tiempos 2018). Initially scheduled for 2011, this was postponed to 2017, and it was recently announced that operations would not begin before the third quarter of 2021 (Correo del Sur 2019). Given the lack of progress, in August 2018, AFP Previsión, owned by Spanish bank BBVA, decided to take the Bolivian government to the International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) (Página Siete 2018a). At the time, the government officials stated that the amount sought by the two AFPs was excessive, yet they underscored their commitment to pay for an orderly exit of the AFPs (Página Siete 2018b). This case is still pending. AFP Futuro has also expressed concerns about the lengthy transition (Página Siete 2018b).

Chile

The Chilean reform of 1981 is a landmark in the history of pension privatization. Given the early introduction of the system, by 2006 savings were high, at around 60 percent of GDP. They declined somewhat in 2008 because of the global financial crisis and then increased to 69 percent in 2016 (OECD 2017). Unlike those in the other reforming countries, private pension administrators were able to diversify their assets and help to develop the capital market. The 1981 reform closed the old PAYG state-run pillar for new entrants, while existing workers at the time of the enactment could stay in the old system or opt into the new private one. Members of the armed forces and the police maintained membership to their existing schemes, which provided a benefit based on final salary and years of membership.

The Chilean private pension market experienced a high degree of concentration, with the number of AFPs reduced to five by 2008. The high level of concentration combined with the high levels of savings transformed the pension industry into a key veto actor in future pension policy changes (Borzutzky Reference Borzutzky2019; Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011). Coverage of the EAP remained high, about 52 percent in 2006, while coverage of the elderly was almost as high, at 60 percent in 2006 (Arenas de Mesa Reference Arenas de Mesa2019, 149).

The policy legacy of the system was thus one of relatively high levels of coverage and savings and a powerful pension industry that would resist re-reforms that seriously limited the weight of the private pillar (Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011). Unlike those of Argentina and Bolivia, Chile’s labor movement did not play a role in the 1981 reform, which was enacted under the military dictatorship. The combination of repression and neoliberal economic policy during the dictatorship weakened the labor movement. Furthermore, deunionization continued during democracy. By 2005, the unionization rate was around 15 percent, much lower than in Argentina and Bolivia (ILO 2020). After the early 2000s, the labor movement expressed its interest in a significant reform of the system, yet it was unable to exert significant influence in subsequent pension reforms (Ewig and Kay Reference Ewig and Kay2011, 82).

Over the years, dissatisfaction with the system focused on the low level of future pensions, especially for low-and medium-low-income workers without steady jobs or self-employed, who might not be covered by a private pension unless they opted into the system. The most significant differences in expected pensions were between men and women (Gobierno de Chile 2006, 8).

Adequacy concerns, and the impact on fiscal costs of workers’ claiming supplementary pensions in the future to have some retirement income, were what mainly drove the first center-left government of Michelle Bachelet to set up a pension commission in 2006, delivering on a promise made during the presidential campaign to review the system (Arenas de Mesa Reference Arenas de Mesa2010, 51). Yet political and institutional factors also dictated the reason the president appointed a commission and then negotiated with the opposition parties for a reform. Her coalition had a narrow majority in both chambers of Congress, with 65 out of 120 seats in the Chamber of Deputies and 11 out of 20 seats in the Senate (Gamboa and Segovia Reference Gamboa and Carolina2006).

While, in principle, this majority allowed for significant changes, Bachelet did not enjoy high levels of power concentration. This was due to several institutional and partisan factors that greatly attenuate the formal strong powers allocated to Chilean presidents (Siavelis Reference Siavelis, Helmke and Levitsky2006). First, due to the characteristics of the transition to democracy, Chilean politics is structured by two main coalitions, the center-left Concertación and the center-right Alianza por Chile. In this context, policies must be negotiated among coalition members and political and economic ministers, aided by independent technocrats (Castiglioni Reference Castiglioni2010; 13). Second, the electoral system of the 1980 Constitution was designed to overrepresent the right (Siavelis Reference Siavelis, Helmke and Levitsky2006). Third, bills that introduce changes to specific policy areas, such as social security, require a special majority, called leyes de quórum especial (Cifuentes and Williams Reference Cifuentes and Guido2019). Overall, this institutional setting meant that the Bachelet government had to negotiate with the opposition and the strong pension industry. The influence of the pension industry was illustrated by the fact that out of 15 commissioners, 5 had strong links to the pension industry (Valdés-Prieto Reference Valdés-Prieto2009, 9).

The commission’s main recommendation was to introduce a first pillar of noncontributory pensions, funded out of general revenues, to improve the condition of low-income workers with no or very low savings in the private pension pillar, and thus reduce future fiscal spending on supplementary pensions. After lengthy negotiations with stakeholders and political parties, an act was passed in 2008 that implemented the bulk of the commission’s recommendations. The reform introduced a first pillar of noncontributory pensions composed of a Pension Básica Solidaria (PBS), granted to those aged 65 and over who were not eligible for any other pension; and an additional pension (Aporte Previsional Solidario, APS), a tapered benefit designed to supplement private pension income and decrease as private pension income increases. It becomes zero at a specific level of private pension income set out by the government (Superintendencia de Pensiones 2021).

The 2008 reform represented a significant structural change that was heavily influenced by the policy legacy of the 1981 reform and the political and institutional setting. This explains why the system of individual accounts remained, albeit with some changes, such as a competitive bidding process for new subscribers (the AFP charging the lowest fees is assigned all new subscribers over two years). It also introduced a more flexible and transparent investment regime.

The maintenance of the private system and the low level of pensions expected for low-income workers represented a significant legacy of this reform (Barr and Diamond Reference Barr and Peter2016). This meant that future reform of the system would remain high in the agenda. This concern was mainly fueled by low-income workers set to lose the most from the private system, who set up the No+AFP movement, which would periodically organize large demonstrations in subsequent years (Borzutzky Reference Borzutzky2019, 12).

Latest Developments and Comparative Conclusions

We theorized that the specific combination of policy legacies and the institutional setting largely shape re-reform outcomes. Table 2 summarizes how the cases analyzed fit our theoretical expectations. Table 3 provides the data for the indicators used to assess the policy legacy and institutional setting in each case.

Table 2. Theoretical Expectations and Cases

Table 3. Summary of Indicators of Legacies and Institutions for Re-reforms, Bolivia, Argentina, and Chile

The Chilean 2008 re-reform was the result of a strong policy legacy, due to the high levels of savings and coverage in the private pillar, a weak labor movement, and a well-organized pension industry, combined with a weak institutional setting, in which the president’s coalition had a majority in both chambers of Congress but needed to attain a special quorum to pass the re-reform and did not concentrate power in her hands, so that she needed to negotiate proposals with her coalition partners. In this context, the re-reform maintained the private pillar largely untouched but significantly expanded the role of noncontributory pensions.

In Bolivia, by the mid-2000s, the policy legacy was low, due to very low levels of coverage in the private pillar, high coverage in the noncontributory Bonosol but with a very low benefit, a rather strong labor movement that opposed the private system, and a small pension industry that nevertheless accumulated assets representing about 22 percent of GDP. In this context, a government facing a weak institutional setting, since it did not control the Senate and could not concentrate power, and having to negotiate with coalition partners, focused on changing the noncontributory Bonosol for the more generous Renta Dignidad, after lengthy negotiations.

Both the Argentine (2008) and Bolivian (2010) re-reforms that significantly altered the private pillar—eliminating it in the former and changing management to the state in the latter—were the result of a weak policy legacy and a strong institutional setting. In the case of Argentina, the legacy was weak due to low savings and coverage in the private pillar (especially for active workers), a strong labor movement that opposed the private system from its inception, and a weakly organized pension industry. This combined with a strong institutional setting, as President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner’s party controlled both chambers of Congress and she had the capacity to make decisions almost in isolation. In the case of Bolivia in 2010, the re-reform was facilitated by the now-strong institutional setting, as the government had large majorities in both chambers of Congress and a considerable degree of freedom from coalition partners.

Although the three countries have not adopted further re-reforms as defined in this study, discussion about further reforms has continued, with policy legacies and institutions still playing a role. This is certainly the case in Chile where, despite a strong policy legacy, concerns about the adequacy of future pensions remain. A new development in recent years has been the emergence of the No+AFP (No More AFP) movement, which has led demonstrations and pressed for the elimination of private pension administrators (Borzutzky Reference Borzutzky2019). President Bachelet, following the recommendations of a commission (Comisión Bravo) set up to address these concerns, introduced a reform bill in Congress in 2017 (Mensaje Presidencial 115—365) that broadly followed one of the commission’s proposals: maintaining the private pillar and introducing a new employer contribution of 5 percent to fund a second pillar run by the state. Lacking enough support in Congress, the bill was not thoroughly debated before the change of administration in 2018.

A strong legacy from the private system and a weak institutional setting also feature in the different re-reform proposals put forward by President Sebastián Piñera when he took over in March 2018. In October 2018, the government introduced a bill that proposed a new employer contribution of 4 percent, which would go entirely to the private pillar. It also proposed a new publicly run pillar to complement retirement income for middle-class earners and women, financed out of general revenues (Macías Muñoz Reference Macías2019). During 2019, as protests against the government gathered momentum, the bill did not make progress in Congress. Piñera’s weakened administration was therefore forced to promise a new re-reform bill.

Finally, in January 2020, a new bill was introduced in the Chamber of Deputies. Once more, the policy legacy of the private system was relevant, as the bill did not contemplate any reduction in that pillar. Quite the contrary: the bill proposed a new 6 percent contribution from the employer, 3 percent of which would go to the existing private pillar. The remaining 3 percent would go to a newly created PAYG pillar. After lengthy negotiations with the center-left Christian Democratic Party (Partido Demócrata Cristiano, PDC), the bill incorporated some changes, such as increasing the benefit for women in the new PAYG pillar and its funding (El Mostrador 2020). In the end, the bill was not considered by the Senate.

In Bolivia, the main legacy of the 2010 reform has been the unfinished transition of the management of private accounts from the AFPs to the new public administrator. While the previous administration admitted that it wanted to find a solution for an orderly exit of the two private administrators (Página Siete 2018a), it is questionable whether this transition will be completed. The election in 2020 of President Luis Arce of the MAS, which also obtained a large majority in Congress, may offer an opportunity to finish the re-reform.

In Argentina, new re-reforms have not been attempted, but concerns remain about the sustainability of the system and the need to implement significant rereforms in the future (Rofman and Apella 2016, 94). The legacy of a system that now has coverage levels of over 90 percent and the specific institutional setting are likely to play a role in shaping future re-reforms. Changes to the indexation formula in 2017 and 2020, even though not re-reforms, were affected by the specific combination of system legacy and the institutional setting. Although the 2017 change was passed only after concessions to political opponents, the 2019 change was passed swiftly, thanks to President Alberto Fernández’s coalition controlling both chambers of Congress and being able to concentrate decisions in his cabinet (La Nación 2019).

Our theoretical framework provides insights to understand other re-reforms in the region and beyond. For example, Uruguay reformed its system in 1996 along the lines of Argentina’s, but membership in the private pillar was mandatory for workers above a certain income (Busquets and Pose 2016). With coverage levels at 76 percent of EAP, savings at about 13 percent of GDP in 2008, and the pension industry concentrated in only six administrators, the policy legacy was strong (Arenas de Mesa 2019). In this context, the center-left Frente Amplio (FA) administration that took office in 2005 decided to lead a reform by setting up a commission and then negotiating its details in Congress (Busquets Reference Busquets2013, 57). After lengthy negotiations with representatives from political parties, the pension industry, unions, and pensioners, a reform package was passed in 2008 that included, among other things, a reduction in the number of years to qualify for a contributory pension and the possibility for those who had voluntarily affiliated with the private pillar to disaffiliate (Busquets and Pose Reference Busquets and Nicolás2016, 7).

The strong policy legacy of a relatively well organized pension industry and strong veto actors, such as pensioners and unions, that played a significant role in the 1996 reform is key to understanding this process. The political institutional setting was weak overall, since even though the government had a majority in both chambers, it was a narrow one, and the president, given the coalitional structure of the government, did not concentrate power (Busquets Reference Busquets2013, 22). Further reform of the system was high on the agenda in the 2019 elections. The newly elected center-right administration of President Luis Lacalle Pou was able to pass a bill in Congress to set up a new pensions commission to consider a wide range of issues (Presidencia Uruguay Reference Presidencia2020). The policy legacies consist of a relatively strong industry and veto actors, such as unions and pensioners; the institutional setting is characterized by an administration that has a minority in both chambers of Congress and an executive that cannot concentrate decisionmaking, as the president’s party is part of a coalition. This means that a future re-reform is unlikely to alter the structure of the private pillar.

Peru also introduced a mandatory private pillar in the late 1990s (Mesa-Lago et al. Reference Mesa-Lago, Nitsch and Hujo2004). The legacy of the private system is strong overall, as it has accumulated savings of about 30 percent of GDP and is concentrated in just four administrators. Yet coverage is still low, about 20 percent of the workforce (Rofman and Olivieri Reference Rofman and María2012). The weak political institutional setting, characterized by governments that consistently lack a majority in Congress and in which the president cannot concentrate decisionmaking, has resulted in failed government reform attempts. In this context, the administration of President Martín Vizcarra (2018—20) was unable to pass a bill to create a commission to undertake a significant reform of the system.

Beyond the region, re-reforms also seem to be the result of the specific combination of legacies and the institutional setting. In Hungary, the legacy of the 1997 reform that introduced a private pillar was that of low coverage levels and significant pressures on public finances, because the state had to pay pensions to workers who had contributed to the previous public system. In the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis, a strong center-right government that enjoyed two-thirds of seats in Parliament and a prime minister, Viktor Orbán, who increasingly concentrated power in his hands, decided to eliminate the private pillar (Sokhey Reference Sokhey2017, 187).

Poland had a similar legacy of a mandatory private pillar with relatively low levels of coverage and savings. The institutional setting in this case was weak, given that the center-right Civic Platform ruling party was in an alliance with the right-wing People’s Party and the prime minister could not concentrate decisionmaking, facing opposition from the powerful Central Bank (Sokhey Reference Sokhey2017, 204). In this context, the government had to negotiate the specific outcome of the reform in Parliament, which ultimately led to the elimination of the private pillar in 2014 (Sokhey Reference Sokhey2017, 192).

The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact in Latin America has sparked a debate on allowing workers to access their private pension savings. While it is too early to properly assess these developments, legacies and institutions seem to have played a role in recently adopted changes. In Chile and Peru, given the strong policy legacy of their private systems but with governments facing a weak institutional setting, opposition parties (with the support of some grassroots movements) have been able to pass proposals to allow workers to withdraw a proportion of their savings (10 percent in Chile and 25 percent in Peru). Proposals to allow further withdrawals are still ongoing (LexLatin 2020; El Universo 2020). These changes could represent examples of policy drift (Hacker Reference Hacker2004), in which opponents of a policy attempt undermine it by introducing changes using the status quo and institutions to their advantage. We contend that more research is necessary to explore these developments.

Concerns about the adequacy of future pensions and the sustainability of those systems in the region and beyond are far from over. The COVID-19 pandemic has raised further questions about the use of pensions to provide relief to affected members. Against this backdrop, our analysis shows that policy legacies and institutions are likely to play a key role.