“Every country has the right to interpret the One China principle in their own way”

– Czech Senate President Milos Vystrčil, September 2020Footnote 1This quote illustrates how the “questions” of Taiwan's status and the tensions inherent in varying interpretations of “one China” are increasingly salient features of European discourse. The relationship between the European Union (EU) and the People's Republic of China (PRC) constitutes one of the world's largest economic dyads, cooperating across a broad spectrum of policy domains under the banner of a “comprehensive strategic partnership.” In pursuit of mutual benefit, the EU committed to a “one China” position – consistent with the policies adopted by member states – when diplomatic relations were established in 1975. Although the policy was not codified, the commission vice-president who led the European delegation to Beijing reported that he “was able to satisfy [the PRC government], in keeping with positions adopted at various times by all the Member States, the Community does not entertain any official relations with Taiwan or have any agreements with it.”Footnote 2

Under the “one-China principle,” the PRC asserts sovereignty over Taiwan; yet European governments refer to “one China” policies, committing to only extend formal recognition to the PRC without acknowledging its claimed sovereignty over Taiwan – implying that Taiwan's future status is yet to be determined. Effective “one China” policies – how international actors engage with Taiwan – are often more expansive and flexible than official positions would suggest. As argued by Liff and Lin in this special section, the prevalence of this distinction in the international community undermines the PRC's claims that the “one-China principle” enjoys universal acceptance.Footnote 3

Adherence to the prevailing “one China policy” went largely unquestioned by European policymakers or citizens for decades. More recently, despite optimistic rhetoric and the general absence of clashing interests, EU–China relations have been beset by a series of challenges as China's influence in Europe increased and, in turn, European policymakers became warier of emerging and future negative consequences. Consequently, European views of the relationship hardened and the dominance of “opportunity” perspectives – dominant in European discourse until around 2016 – weakened.Footnote 4 The PRC's treatment of Uyghurs in Xinjiang and protesters in Hong Kong and its threats to Taiwan have made headlines across European media, fuelling concerns about the PRC's repressive character. In parallel, and partly as a response, the issue of Europe's “one China policy” has generated unprecedented contestation in European political and foreign policy discourse.

This article examines the evolution of the EU's effective “one China policy” and evaluates whether its stance is consistent with the idea of the EU embodying a “normative power” – arguably the dominant perspective within the EU foreign policy literature. The normative dimension around the “one China policy” is stark: the PRC is non-democratic and does not share the EU's fundamental values; Taiwan's political system and substantive values are compatible with Europe's. A central contention of the Normative Power Europe (NPE) concept is that the EU is willing to impinge on the norm of state sovereignty to promote its values; if this is correct, we would expect the EU to be unconcerned by the PRC's claims that other countries’ relations with Taiwan interfere in its domestic politics and allow pursuit of cooperative relations with Taiwan as a fellow democracy.

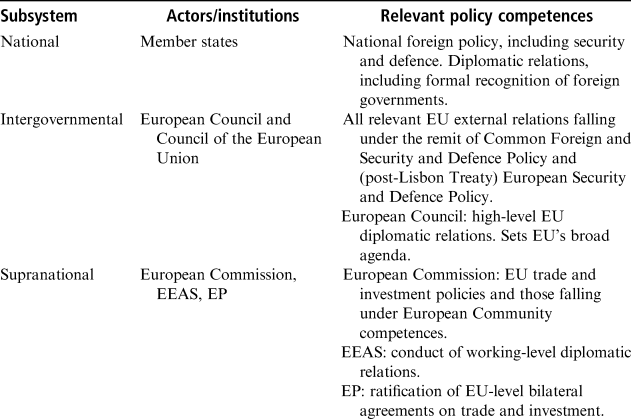

I employ a subsystems framework, arguing that the EU's foreign policies – rather than a singular policy – are created through three venues. The EU's unusual international presence results from the existence of member states’ foreign policies alongside the common foreign policy project. Owing to the very nature of EU foreign policymaking, the maintenance of coherent common positions is often difficult, and the question of “one China” and policies towards Taiwan is no exception. Subsystems analysis allows for a nuanced approach to the evolution of the European “one China policy” – or rather, policies. Adherence to a singular interpretation of “one China” has begun to weaken within Europe; the edges are fraying as different actors pull at the threads. Rather than a normatively driven, top-down decision to bolster EU relations with Taiwan, Europe's approach has been changed by incremental moves by member states (the national subsystem) and actors within certain EU institutions (the supranational subsystem). The EU now finds itself in an awkward position not of conscious design, creating a policy coherence problem – thereby challenging the concept of the EU as a collective normative actor, even if individual actors and/or governments are motivated by normative considerations.

While EU–China scholarship has exploded over the past decade, questions on Taiwan, “one China” and cross-Strait relations have not featured prominently. Some scholars put Taiwan at the centre of their researchFootnote 5 and some volumes on EU–China or EU–Asia relations have featured individual chapters on Taiwan.Footnote 6 Taiwanese scholars have contributed considerably to what literature there is on the relationship.Footnote 7 Economic relations tend to dominate,Footnote 8 as they provide the most “meat” for scholars to sink their teeth into. Though relatively scarce, the existing scholarship is of high quality.

Given developments in EU–PRC–Taiwan relations, this paper makes a timely contribution. It considers the changes in EU–Taiwan relations and what this means to the EU as an international actor attempting to balance managing relations with other systemic powers while putatively projecting values and norms it expects others to embrace. The application of the normative power framework fills a gap in the EU–Taiwan relations literature. This is pertinent as normative arguments are prominent in political discourse – i.e. what the EU should do vis-à-vis Taiwan. For instance, Dekker advocated for greater EU attention to Taiwan, a “normative, like-minded actor.”Footnote 9 James argued the EU “maintaining a neutral position on Taiwan's sovereignty will not be a matter of passive indifference but of active decision.”Footnote 10 Through the theoretical lens of normative power, this raises the question of whether the EU will let the PRC determine what constitutes the norm of Taiwan's sovereignty, whether it will seek to enable Taiwan's democratic government to determine this norm or whether it will actively try to (re)shape the norm itself. I do not seek to answer such questions – rather, they serve as guidelines for understanding the evolution of triangular relations.

The next section details the production of EU foreign policy from within three subsystems. Thereafter, I introduce the normative power/actor concept. The following section examines developments in EU–China relations and its impact on the EU's “one China policy.” I conclude by reflecting how the dynamics of the EU–PRC–Taiwan relationship were influenced by activities within the EU's subsystems and what this means for the EU's status as a normative actor.

My argument develops as follows: The late 2010s and early 2020s witnessed increased salience of Taiwan-related concerns within the EU's foreign policy subsystems. The greatest enthusiasm for enhanced relations with Taiwan comes from the national subsystem; national parliamentarians were notably proactive on the issue and a few select governments became more assertive. Despite practically deepening relations with democratic Taiwan, all member states continued to officially recognize only the PRC as a sovereign state, while denying explicit recognition to, or official diplomatic relations with, Taiwan. Though unofficial ties with the latter are deepening, this core position on “one China” does not appear to be under threat based on the available evidence. Nevertheless, louder calls for enhanced relations with Taiwan have been expressed from within the supranational subsystem, primarily the European Parliament (EP) – a finding congruent with existing research on the EP's advocacy of values-based foreign policies.Footnote 11 Furthermore, European Commission (hereafter the Commission; also part of the supranational subsystem) officials became more vocal on political problems in China relations, whereas in the past they focussed on the trade relationship and avoided involvement in political debates (often viewing these as the responsibility of the intergovernmental European Council and Council of the EU). Resultantly, the EU's “one China policy” core is untouched, but the edges are fraying.

EU foreign policy subsystems

The EU is unique among major international actors examined in this special section in that competences (powers) over external-facing policies are divided into different levels and across institutional settings. This operates in parallel to member states retaining sovereign control over critical components of foreign policies, particularly diplomacy, security and defence – although these dividing lines are blurred in some respects following the Lisbon Treaty's expansion of the EU's foreign, security and defence policy capacities. Drawing on scholarship that developed the subsystems analytical framework and my previous research,Footnote 12 I expound on the competences and associated institutions/actors summarized in Table 1. This lays the groundwork for understanding the challenges in creating and maintaining coherent policy positions.

Table 1. The EU's Foreign Policy Subsystems

Sources: Derived from Brown Reference Brown2018; Stumbaum Reference Stumbaum2009.

National subsystem

Member states retain control over diplomatic (including formal recognition of other states), security and defence policies. Despite incremental integration and intensified cooperation within these domains, ultimately national governments chart their own course. Despite numerous areas where overlapping interests and preferences facilitate convergence around common positions, notable exceptions remain where member states diverge on sensitive topics. Individual governments’ positions need to be considered as a subsystem in parallel with the output of the EU-level subsystems. Importantly, member states have the power to determine their national “one China” policies and are not bound to a single formulation. Member states can determine to have their own offices in Taiwan and accept Taiwanese offices in return. Although it is widely accepted that the EU has adhered to a “one China policy” since 1975, this was – as shown above – articulated as consistent with the position of its then member states. It is beyond this paper's scope to examine all member states’ positions; instead, I focus on cases where member states acted in ways diverging from the established norm, or where national-level actors signalled support for expanding relations with Taiwan. Despite Brexit, the United Kingdom is included due to its central role in shaping EU–China relations.Footnote 13

Intergovernmental subsystem

The intergovernmental subsystem involves member state representatives coordinating and negotiating the substance of common foreign policy positions. The European Council – comprised of heads of government/state – is central to agenda setting and decision making. By adopting official “strategies,” the European Council is responsible for framing the orientation of common foreign policy and relations with individual third parties. The Council of the EU (aka the Council of Ministers or, simply, the Council) meets in various compositions determined by the policy domain under consideration. Here, key policies are deliberated and shaped, with decision making depending on unanimity – albeit, in reality, member states are by no means equal; the “usual suspects” of France, Germany and the UK hold the greatest sway. This subsystem is the source of the codified EU-level “one China policy” (see below) and thus any change would emanate from here.

Supranational subsystem

The Commission, European External Action Service (EEAS) and EP constitute the three supranational institutions involved in external relations. Conventionally, EU-level foreign policy has been conceptualized as a primarily intergovernmental enterprise – however, scholars have demonstrated supranational actors’ growing importance.Footnote 14 The Commission's importance stems from its trade policy competence, albeit operating within the parameters of the European Council's agenda. Essentially the EU's executive arm, the Commission enjoys considerable autonomy in terms of policy implementation, a non-exclusive right of initiative, and access to information to rival that of the member states. Commission officials have their own preferences, frequently advocating for an EU “voice” and greater institutional empowerment.Footnote 15

The EEAS is headed by the high representative for foreign and security policy, who is simultaneously a Commission vice-president. The EEAS is responsible for coordinating between EU institutions, the conduct of the day-to-day diplomatic representation and implementation of certain EU policies. The EEAS operates the European Economic and Trade Office in Taiwan, effectively the EU's unofficial delegation – albeit its website stresses that “in line with the EU's ‘one China’ policy…[it] is not engaged in relations of a diplomatic nature,” recognizing Taiwan as an “economic and commercial entity.”Footnote 16

The democratically elected EP provides supranational representation of the citizenry. Despite relatively limited formal control over foreign policymaking, it exerts influence through (re)shaping policy discourse and scrutiny of Commission and EEAS officials. Resolutions are frequently used to express the EP's position on issues – a mechanism used extensively with respect to both the PRC and Taiwan. The EP has powers of ratification concerning trade and investment deals, giving it considerable power over foreign economic policy. Members of the EP are not subjected to the same kinds of party discipline found within national parliaments, thus there is greater scope for independence to set out positions national leaders/governments may be reluctant to commit to.

The EU: Normative Actor?

Arguably, Manners's NPE has become the most widely used concept attempting to encapsulate the EU's sui generis international presence and has transcended academia, making its way into the lexicon of EU elites.Footnote 17 This concept has something to say about how the EU will or should generally behave in interactions with third parties. NPE can be employed to explain EU policies and actions and/or as an “ideal type” model from which expectations of future behaviour can be generated (and against which actual outcomes can be measured). Here, I consider NPE's usefulness for understanding the EU's effective “one China policy.”

NPE holds that the EU's foreign policies are guided by a set of norms that flow from its unique make-up and, in turn, are projected externally. Thus, the EU is both the product and promoter of specific values. Consideration of Europe's normative identity and action is widespread in EU–China research but conspicuous in its absence from the EU–Taiwan literature.Footnote 18 Manners claimed that normative power is a distinctive form of power with an independent ideational impact. It is not just a form of power possessed: the EU's very actions are motivated by its normative identity, reflecting a desire to shape the existing norms of the international sphere – to redefine what is considered “normal.”Footnote 19 Manners identified the “willingness to impinge on state sovereignty” Footnote 20 as a component of the EU's touted normative power; in the context of EU–Taiwan relations, this opens the door for expanding and deepening interactions despite PRC claims of interference in domestic affairs.

Manners identified five “core” norms constituting the EU as a polity and which are central to its external objectives: peace, liberty, democracy, the rule of law and respect for human rights.Footnote 21 Manners argued “a more normative type of actor would be one on a normative heading towards an ideal type of a normative power.” Footnote 22 Thus we can think of the EU as behaving more or less normatively with respect to Taiwan. In terms of political character, Taiwan is normatively aligned with the EU owing to commitment to democracy and shared values – and it has become more so as its democratic transition has consolidated and matured since the 1990s. If the EU is a normative actor, then it has (or should have) an interest in promoting relations with Taiwan, respect for its de facto autonomy, and support for its population's democratic right to determine their own destiny. Regarding the “one China policy,” an approach incorporating core norms would ensure the maintenance of peace in cross-Strait relations and defence of Taiwan's liberal democratic system from PRC interference. If the “one China policy” is being challenged in favour of greater support for Taiwan, then we can examine whether this is driven by normative considerations or not.

Shifting European Perceptions of the PRC, Taiwan, and Implications for the EU's Evolving “One China Policy”

In 2009, Fox and Godement characterized the EU's policy approach to China through the 2000s as one of “unconditional engagement” due to a willingness to engage economically and diplomatically, compromising on core values while asking for little, if anything, in return.Footnote 23 Even as China became more powerful internationally and more regressive domestically, the EU's fundamental approach of engagement remained constant. Brown argued this was driven by the dominance of perceptions of China's rise as an “opportunity” – especially in the economic domain, but also politically as a “target” for the EU to socialize into the Western-led international order – and the distinct absence of perceptions of either military/security or ideological/political threats.Footnote 24 Some member states interpreted China as an economic threat in limited respects, but the overall picture was positive.

Since 2016, European perceptions of the PRC have hardened, in some cases quite dramatically. While the engagement strategy remains mostly intact, enthusiasm has waned. The PRC's treatment of Hong Kong and Uyghurs in Xinjiang, alongside its increasingly assertive foreign policy and use of coercive diplomacy, challenges to the rules-based international system, and the intensified great power rivalry with the US all catalysed change in European perceptions and policies. This shift was exemplified by two policy changes in 2021. In March, the Council of the EU imposed sanctions against Chinese officials over human rights violations in XinjiangFootnote 25 – the first new EU-level sanctions against China in more than 30 years. In May, the EP froze the ratification of the EU–China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment.Footnote 26

This section considers developments relevant to the EU's “one China policy” and relationship with Taiwan. I focus on post-2016 events, tracking the emergence of perceptions of China's rise constituting a threat (more commonly featured in US discourse). This has been accompanied by greater attention on Taiwan in the national and supranational subsystems. Not all developments can be analysed; I select a few pertinent cases meriting attention due to their significance for understanding dynamics in EU–PRC–Taiwan relations. It is important to contextualize these appropriately: I do not claim these are representative of the overall pattern of relations. Indeed, continuity has prevailed over change in the EU's strategy of engagement and adherence to its “one China” position. Nevertheless, the growing prominence of Taiwan as a component of the discourse on EU–China relations and incremental moves within the national and supranational subsystems indicates a political shift – previously, European policymakers were relatively reluctant to “rock the boat.” Growing concern about the implications of China's rise broadened the discursive space for Taiwan to emerge as a “live issue” on the EU's agenda.

The PRC's behaviour changes and hardened European perceptions

Various aspects of China's behaviour contributed to hardening European perceptions and policy changes. After an initially positive reception, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has been viewed as allowing China to acquire political and economic influence in Central and Eastern Europe at a “cheap price.”Footnote 27 Despite initial positive reception, this fostered concern among Western European capitals – including Brussels, Berlin, London and Paris – that China was pursuing a divide-and-conquer tactic, undermining attempts to foster a coherent strategic response. In parallel to the BRI's development, China increased its outward investment in technology and critical infrastructure – including ports and nuclear power stations. Such investments raised questions regarding China's intent, particularly as its assertiveness on the global stage became more apparent. Thus perceptions of threat to European interests grew, challenging dominant views of China's rise as primarily an economic opportunity.Footnote 28 European disenchantment with the BRI appeared to be confirmed in May 2021 when Lithuania withdrew from the “17+1” group – meetings between European states and China to promote trade and investment via the BRI. Lithuania's foreign minister argued that the EU “is strongest when all 27 member states act together along with EU institutions” and called for other 17+1 members to follow suit.Footnote 29

Revelations of widescale human rights abuses inflicted upon the Uyghur population in Xinjiang also fuelled disquiet in Europe. The incarceration of up to one million Uyghurs in what the PRC calls “re-education camps” (but which human rights organisations liken to concentration camps) garnered widespread criticism. In October 2019, 15 member statesFootnote 30 and seven other countries produced a statement calling on the PRC to uphold its commitments as a member of the United Nations Human Rights Council.Footnote 31 In December 2019, the EP adopted a resolution condemning the treatment of Uyghurs and ethnic Kazakhs, calling for immediate camp closures. Despite lacking control over relevant policy levers, members of the EP called upon the Commission to consider targeted sanctions against responsible PRC officials.Footnote 32 Despite the introduction of the new “global human rights sanction regime,” an immediate move to use this was ruled out.Footnote 33 Nevertheless, this tool was eventually employed against select PRC officials in March 2021 (see above). This suggests a shift towards greater normative-based action and away from “unconditional engagement.”

Growing attention on Hong Kong, especially during 2020, further exemplifies this trend. Europeans have closely followed the pro-democracy movement, which is a pointedly sensitive issue for the UK. The Sino-British Joint Declaration ostensibly established limits to the PRC's control via the “one country, two systems” framework.Footnote 34 The passage of the 2020 National Security Law (NSL) eroded various aspects of Hong Kong's democratic system, leading activist groups to disband and mass resignations of pro-democracy legislators.Footnote 35 Following the NSL's introduction, the Foreign Affairs CouncilFootnote 36 expressed “grave concern” and declared “political support for Hong Kong's autonomy under the ‘One Country, Two Systems’ principle, and solidarity for the people of Hong Kong,” accompanied by a package of measures (albeit relatively minor and mostly symbolic).Footnote 37 While these actions were relatively limited, the response was notable for contradicting the prevailing assumption the EU – particularly via intergovernmental venues – is reluctant to challenge China on human rights/democracy issues for fear of economic repercussions.

As noted by Chen in this special section, Beijing has pursued a diplomatic pressure campaign towards Taiwan since 2016.Footnote 38 During 2020–2021, the PRC ramped up its military intimidation strategy against Taiwan by sending waves of military aircraft into Taiwan's air defence identification zone.Footnote 39 These provocations – and what they potentially foreshadow – prompted negative reactions from European policymakers, who maintain cross-Strait relations must be conducted peacefully with changes to the status quo agreed bilaterally. Addressing the EP in October 2021, Commission Vice-President Margarethe Vestager explicitly drew attention to China's military pressure on Taiwan, arguing “displays of force may have a direct impact on European security and prosperity.”Footnote 40 Vestager emphasized European interests rather than values – nevertheless, openly addressing the issue served as a reminder that the EU's “one China policy” is not synonymous with the PRC's position. This arguably represented a positive response to the Biden administration's efforts to rally allies in support of its pushback against China's assertiveness towards Taiwan.Footnote 41

These select examples illustrate the changing environment of EU–China relations: receptivity to economic incentives was dialled back, with normative and security concerns reflected in both policy discourse and substance. This created an atmosphere conducive to unofficial relations with Taiwan receiving renewed attention.

A new European perspective on Taiwan and the effective “one China policy”?

Here, I consider what the preceding section's findings and developments in bilateral EU–Taiwan relations mean for the sanctity of the European “one China policy” or policies. The cases of Xinjiang and Hong Kong are illustrative precisely because Beijing insists the Taiwan question is an intrinsically vital component of the “Chinese” national identity; assertions of authority over Xinjiang and Hong Kong could foreshadow plans for Taiwan. As above, I make no claim to comprehensive analysis – select pertinent cases are used to ascertain whether normative considerations motivate European policies.

The EU did not include the “one China policy” in official documentation until its 2003 China policy paper published to coincide with the formal strategic partnership declaration. This document, and by extension the “one China policy,” was drafted by actors within the intergovernmental subsystem, requiring consensus among member states’ representatives. Instead of clearly defining the “one China policy,” the document referred to the “EU interest in closer links with Taiwan in non-political fields, including in multilateral contexts, in line with the EU's ‘One-China’ policy.”Footnote 42 The 2006 policy paper provides slightly more clarity: “on the basis of its ‘one China’ policy, and taking account of the strategic balance in the region, the EU should continue to take an active interest [in maintaining cross-Strait peace and stability], and to make its views known to both sides.” Opposition to “unilateral changes” to the status quo and/or the use of force in cross-Strait relations was expressed, favouring “pragmatic solutions…confidence building measures” and dialogue.Footnote 43 Lee noted the EU's “one China policy” does not entail acceptance of PRC sovereignty over Taiwan, whereas explicit acceptance of the “one-China principle” would.Footnote 44 Coppieters argues that the EU's “one China policy” “takes an open-ended position on Taiwan's final status, including on questions of sovereignty, international personality and citizenship”Footnote 45 – a clear point of differentiation.

The “one China policy” eschews official diplomatic relations or recognition of Taiwan as a sovereign state. It allows the EU to maintain economic and cultural ties with Taiwan while notionally steering clear of “political” relations – although what is “political” is not clearly defined. This ambiguity and inherent flexibility in the EU's vague official position is exemplified by the annual EU–Taiwan human rights consultations launched in 2018, wherein the EU is represented by EEAS officials.Footnote 46 In 2021, the EU had reached the position whereby a Commission vice-president could deliver a speech entitled “EU–Taiwan Political Relations and Cooperation” (emphasis added). At face value, this contradicts the formal limits of the EU's own “one China policy.”Footnote 47 This indicates a change taking place in the supranational subsystem whereby the Commission and the EEAS are openly engaged in the conduct of political relations with Taiwan – essentially inconceivable a few years prior. These shifts in effective policy and practical engagement have occurred even though the EU's official position – or that of its member states – on “one China” has not actually changed.

The upgrading of relations has been incremental, starting with economic ties. The 2015 Commission trade strategy outlined its intent to negotiate an EU–Taiwan bilateral investment agreement with Taiwan to enhance economic interactions.Footnote 48 This was contingent on the successful completion of an agreement with the PRC which, despite progress, was frozen by the EU in 2021. It would also require a Commission impact assessment and subsequent recommendation to the European Council to launch negotiations. Such an investigation could prove problematic due to what Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan described in 2020 as the “broader [political] implications” of a prospective EU–Taiwan agreement.Footnote 49 Although the Commission – a supranational actor – negotiates deals, ultimate approval authority rests in the intergovernmental subsystem with the European Council.

Select European states have paid greater attention to East Asian regional security since approximately 2018, at least implicitly in response to China's growing power and concomitant destabilizing effects. This brings with it a heightened awareness of China's regional assertiveness and the precarity of the cross-Strait dynamics. Until recently, conventional wisdom held that European governments generally did not perceive China's rise as posing security/military threats or, to the extent that it did, that this was a matter for the US. China's negative reactions to increased European regional involvement further strained relations and catalyzed greater scrutiny of its behaviour towards Taiwan.

The EU's 2019 “Strategic Outlook” policy paper on EU–China relations – drafted by the Commission and the High Representative (supranational subsystem) – labelled China as a “systemic rival” for the first time.Footnote 50 However, it was also designated a “cooperation partner,” “negotiating partner” and “economic competitor”Footnote 51 – nuance that was absent from much of the commentary.Footnote 52 The “Strategic Outlook” was never adopted as official strategy, indicating continuity in the overarching intergovernmental EU policy orientation. Despite claims the “Strategic Outlook” represented a new, tough approach, there was no mention of Taiwan outwith reaffirmation of the “one China policy.” Similarly, the EU's “Strategy for Cooperation in the Indo-Pacific” briefly references Taiwan as a partner but did not address the “one China” issue. The document highlighted “increasing tensions in regional hotspots such as in the South and East China Sea and in the Taiwan Strait,” but avoided criticism of the PRC's role therein.Footnote 53 This was likely a necessary concession to ensure that the intergovernmental Council would adopt the strategy – more assertive language would be objectionable to member states still reticent to criticize China.

The 2019 “French Strategy in the Indo-Pacific” notably does not reference the “one China policy,” Taiwan or cross-Strait relations. While reaffirming France's strategic partnership with the PRC, it hints at the potentially destabilizing impact of its rise and rivalry with the US. The document only briefly invokes normative values such as human rights and the rule of law – while democracy is not mentioned.Footnote 54 In March 2019, French President Emmanuel Macron stated that “the period of European naivety is over…[and] the relationship between EU and China must not be first and foremost a trading one, but a geopolitical and strategic relationship.”Footnote 55 In April, China accused a French navy vessel navigating the Taiwan Strait of “illegally entering Chinese waters.”Footnote 56 France asserted the operation was routine and compliant with freedom of navigation laws – though one Taiwanese military official stated it was “rare enough to make it a political statement.”Footnote 57 Arguably, the timing – shortly after Macron's statements – was not coincidental. Though France was not signalling a reinterpretation of “one China,” its strategic thinking had altered.

The UK government has sent ships through the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait since 2018,Footnote 58 ostensibly motivated by US calls for support. This predictably provoked criticism from the PRC for interference with regional matters.Footnote 59 The PRC's military attaché to the UK warned that ships in the South China Sea could be met with an armed response.Footnote 60 Although the UK, like other external actors, officially sides with no individual disputant, the South China Sea disputes are highly sensitive for the PRC, not least because Taiwan also claims some contested territories. In June 2019, Germany was reportedly considering sending a warship through the Taiwan Strait, although no such operation was announced subsequently. Commentators suggested Merkel's government was interested in signalling to the US that it was a committed ally with a stake in regional security.Footnote 61

The “one China” issue surfaced in German politics in December 2019, following a popular petition in support of diplomatic relations with Taiwan. The petition was initially rejected for publication by the Bundestag's petitions committee following advice from the Federal Foreign Office that it would contradict Germany's “one China policy.”Footnote 62 The head of the Foreign Office's Asia Department, Petra Sigmund, subsequently explained: “For [Germany], Taiwan is part of China” and that the PRC is recognized as the “only sovereign state in China.” Pushed by parliamentarians, Sigmund explained recognition of Taiwan would “seriously damage” relations to the detriment of German interests on global challenges such as climate change.Footnote 63 Many parliamentary groups welcomed the petition, indicating a split between Germany's executive and legislative branches on the appropriateness of maintaining the “one China policy's” status quo.

Germany's 2020 Indo-Pacific regional strategy was criticized for ignoring Taiwan.Footnote 64 Examining the paper, the “one China policy” is not mentioned once.Footnote 65 The development of the strategy in and of itself was said to represent “a wider European turn against China.”Footnote 66 Even if this perspective does not reflect Germany's position (as the evidence suggests), it is reasonable to infer the PRC would interpret it this way. At the time of writing, Germany's incoming government outlined a tougher stance on China policy, promising to stand up for values and signalling a more pro-Taiwan orientation. It remains to be seen how this will change policy, yet the plans themselves prompted a Chinese foreign ministry official to call on Germany to “respect China's core interest.”Footnote 67

Taiwan's status is not just of interest to the “big three” European states. Developments indicating broader dissatisfaction among national parliamentarians with their governments’ positions were witnessed in 2020–2021, across Europe. In July, the Belgian Parliament passed a resolution calling on the government to support freedom and democracy in Taiwan, expand bilateral cooperation, support Taiwan's participation in international organisations and work within the EU to strengthen EU–Taiwan relations.Footnote 68 Although the Chamber of Representatives cannot compel the government to change positions, the resolution's content clearly evinced normative-based arguments for closer Belgium–Taiwan and EU–Taiwan relations.

A Czech delegation, including Senate President Milos Vystrčil, visited Taiwan in August 2020, despite PRC warnings. The response from China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi – claiming Czech parliamentarians had “crossed a red line” – precipitated a backlash. Czech Foreign Minister Tomáš Petříček claimed these comments went “over the edge” and “such strong words do not belong in the relations between the two sovereign countries.”Footnote 69 Vystrčil defended the trip as consistent with the Czech Republic's “one China policy.”Footnote 70 Wang was criticized by Germany's foreign minister, describing the comments “not appropriate” and pointed out the EU treats its international partners “with respect” and expected “exactly the same in return.”Footnote 71 This pushback is significant, as historically member states – particularly smaller countries more vulnerable to Chinese pressure – were reluctant to respond to (or openly disagree with) the PRC, preferring to shelter behind collective EU responses. Despite retaliatory threats, the Czech government forcefully responded to China's coercive diplomacy while defending the rights of national politicians to undertake official visits to Taiwan. Germany stepping in was also significant, given criticism over its perceived reluctance to stand up to the PRC.Footnote 72

In addition to souring perceptions of the PRC, the politics of the COVID-19 pandemic helped to raise Taiwan's profile globally, as Kastner et al. make clear in this special section.Footnote 73 Europe was no exception. The EU's initial help provided to China in early 2020 and the perceived success of China's so-called “mask diplomacy”Footnote 74 initially indicated benefits for the EU–PRC relationship. However, Taiwan's effective handling of the pandemic and provision of personal protective equipment to European nations sparked renewed support for Taiwan's elevation to observer status in the World Health Organization – a position which was opposed by the PRC. The Taiwanese government donated millions of masks to EU countries, prompting Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to tweet thanks for the “gesture of solidarity.”Footnote 75 Commissioner for Crisis Management Janez Lenarčič stated: “in these difficult times, international cooperation is crucial. We highly appreciate Taiwan's gesture of solidarity with its donation of medical masks.”Footnote 76 These statements are significant because prominent Commission officials within the supranational subsystem recognized Taiwan as an entity outwith the economic or cultural domains where the EU-level “one China policy” permits interaction. Historically, the Commission was less willing to risk China's repudiation. The emphasis on solidarity in these statements is consistent with normative framing of EU external relations.

Per Kastner et al. in this special section, seven member states expressed support for Taiwan's WHO participation, while a total of 14 praised Taiwan's COVID-19 response and/or related foreign aid.Footnote 77 In May 2021, the French Senate unanimously passed a resolution endorsing Taiwan's participation in the WHO while asserting consistency with formal relations with the PRC.Footnote 78 Support for Taiwan came not only from the “big three” but also smaller EU states, such as the Czech Republic, Lithuania and Slovakia (all appearing in both categories) despite belonging to the 17+1 group. China reacted negatively to any sign of EU–Taiwan engagement, criticizing the Czech Republic for launching a co-operative pandemic research project with Taiwan.Footnote 79 Still, it must be acknowledged that only half of the EU's members (counting the UK) praised Taiwan; this split indicates the difficulty of addressing Taiwan relations when the intergovernmental subsystem ultimately requires consensus decision making.

Owing to the PRC's initial reticence to divulge the extent of its epidemic and subsequent criticisms of the EU, Fürst argued Taiwan was “the ‘side-winner’ of the public diplomacy competition,” projecting an image of itself “as the country that successfully coped with the epidemic, and a provider of health material and know-how.”Footnote 80 The EU's representative in Taiwan, Filip Grzegorzewski, remarked: “Taiwan has carved out a reputation in Europe as a well-governed place that can bring a lot to the international community and global cooperation, both in terms of health protection and economic partnership.”Footnote 81 Although positive perceptions of Taiwan and co-operation during the pandemic do not indicate a direct challenge to the “one China policy,” it is notable that European policymakers – including those within the EU institutions – became less cautious about adhering to Beijing's insistence on limited engagement with Taiwan.Footnote 82

One key development of national-level relations came in 2021 when the Taiwanese Representative Office in Vilnius, Lithuania, opened. The office, the first of its kind in Europe for almost two decades, will operate as a de facto embassy, despite Lithuania sticking to a non-recognition policy.Footnote 83 The office's official name included Taiwan as opposed to Taipei – a symbolic victory for diplomatic presence following a period when the PRC had successfully whittled down the number of actors formally recognizing Taiwan. The PRC described Lithuania's decision as “wrong” and an “extremely egregious act” and withdrew its ambassador after the plans were first confirmed.Footnote 84 An EU spokesperson was quoted as confirming the EU's position that this was not “a breach of the EU's One-China policy” and pointed to the EU's support for Lithuania “in the face of sustained coercive measures from China.”Footnote 85 The US offered both political and economic support to Lithuania following the office's opening, demonstrating the US would support European allies’ efforts to enhance political ties with Taiwan.Footnote 86

These examples evince shifts in EU–PRC–Taiwan dynamics that are at odds with how the EU previously operationalized its own “one China policy” but also clearly exemplify the inherent flexibility of the “one China” framework in practise. Yet they provide limited evidence of coordination between European actors. Most activity originated from the national (i.e. member states) and supranational subsystems – primarily the EP but also the Commission to an increasing degree. In October 2021, the EP voted overwhelmingly in support of a resolution calling for closer relations with Taiwan – including what would be a significant symbolic move by renaming the “European Economic and Trade Office” to the “European Union Office in Taiwan.”Footnote 87 The EEAS's human rights consultations with Taiwan are symbolically significant as it is difficult to argue that this is not a political interaction. The 2021 consultation's joint press release alluded to normative congruence: “Taiwan and the EU are like-minded in many ways and share common values, such as the respect for human rights, democracy and the rule of law.”Footnote 88 In late 2021, the Commission was reportedly working on a “confidential plan” to introduce a “new strategic format for liaising with Taiwan” on a range of issues.Footnote 89 At the time of writing, these plans had not been formally announced – thus their implications remain to be seen, if they do indeed come to fruition.

The intergovernmental subsystem barely touched the question of EU–Taiwan relations during the timeframe of this study. The overall picture for the EU's official “one China” position is relatively stable. Yet the EU is composed of a multitude of institutions and actors capable of shaping foreign policies; my analysis has produced evidence of incremental shifts in approaches to Taiwan, in the direction towards greater engagement, despite the EU's officially unchanging 1975 position on “one China” itself. Regarding normative motivations, the cases above showed that national and EP parliamentarians frequently invoke Taiwan's liberal and democratic character as justification for closer relations and greater support. Applying the NPE model to the EU as a collective/unitary actor would suggest that the prevailing approach to Taiwan and the “one China policy” is not particularly normative – economic interests and stability of EU–PRC relations dominate. By looking at the EU's three subsystems, we can identify normatively motivated actors advancing policy preferences that challenge the prevailing operations of “one China” policies in small but nevertheless significant ways. Such behaviour arguably eschews the aforementioned EU-level priorities in favour of calling for policies that reflect European values and supports their development in Taiwan.

Conclusion

The EU's official position on “one China” has not changed – but it has also never been fully aligned with the PRC's “one-China principle.” Recent developments across Europe demonstrate that this distinction has allowed meaningful shifts in effective policies towards Taiwan, even without any official divergence from a decades-old position. Indeed, despite hardened perceptions of China's character owing to its assertive foreign policies and increasingly repressive domestic policies, there is little evidence to suggest that the “one China” frameworkFootnote 90 in international politics is fundamentally being challenged in Europe. Nevertheless, relations with Taiwan moved further up the foreign policy agenda within the EU's subsystems as the EU–PRC relationship has worsened. The available evidence points to incremental changes owing to a variety of actors becoming emboldened to push for a more normatively oriented approach, rather than a centralized EU-level decision to adopt a normative stance towards China and Taiwan.

The greatest push for broadening relations with Taiwan originated in the national subsystem – but member states continue to recognize only the PRC and defend their positions as consistent with both their national and the EU's “one China” policies. In the supranational subsystem, the EP expanded the discourse of how the EU should interact with Taiwan, while the Commission moved beyond dealing only with economic and cultural matters. The intergovernmental subsystem – responsible for EU-level common positions – has not seriously revisited the “one China policy.” Through conceptualizing the EU's external relations as the product of these distinct but interconnected subsystems, I argue the core of the “one China policy” remains untouched but increased European engagement with Taiwan indicates that it is “fraying at the edges.”

Although the recent deepening of EU–Taiwan relations has been incremental, it is significant in two further respects: first, challenging conventional wisdom that EU policies towards the PRC are driven exclusively by material (especially economic) interests and, second, that China's growing power drives normative considerations further down the EU's agenda owing to reduced capacity for influencing its behaviour. This partly reflects a reorientation towards normative positions as the negative effects of China's rise on Europe became more apparent. Instead of conceptualizing the EU as a collective normative actor, identifying normative/normatively motivated actors within policy subsystems is better suited to understanding where and when normative policies emerge. The NPE lens applied to subsystems provides nuanced insights into how these new normative preferences can be understood as conflicting with the “one China” framework as a norm conditioning external relations.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Adam Liff and Dalton Lin for the invitation to contribute to their project and invaluable comments and support through the writing process. Thanks to the two anonymous reviewers who provided extensive feedback that allowed me to strengthen the paper. Thanks also to Jarrod Hayes for helpful feedback early in the paper's development. I am also grateful to the other participants of the “One China Framework and World Politics” workshop – Yu-Jie Chen, Miki Fabry, Scott Kastner, Margaret Pearson, Laura Phillips-Alvarez, Guan Wang and Joseph Yinusa – for insightful comments during our interactions.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Biographical note

Scott A.W. BROWN joined the University of Dundee as lecturer in politics and international relations in 2018. His research focuses on the EU's external relationships engaging with both international relations theory and foreign policy analysis. A primary focus of this work is the EU–US–China relationship, and the bilateral relations within this triangle. His first book, Power, Perception and Foreign Policymaking: US and EU Responses to the Rise of China, was published in 2018 by Routledge, with a paperback edition following in June 2021. Between 2016 and 2018, he was a post-doctoral fellow in the Center for European and Transatlantic Studies at the Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology. He completed his PhD at the University of Glasgow.