Introduction

The earliest evidence of monumentality in eastern Africa coincides with the initial spread of food production into sub-Saharan Africa during a period of profound climatic, economic and social change (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Stewart and Barthelme1984; Garcin et al. Reference Garcin2012; Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018). Animal herding spread into the region via the Turkana Basin of northern Kenya c. 5000 years BP at the end of the African Humid Period; desertification of the Sahara at that time propelled mobile pastoralists into sub-Saharan Africa. Lake Turkana shrank dramatically during this period and people began constructing megalithic cemeteries, known as ‘pillar sites’, near its shorelines. These sites are named for their arrangements of columnar basalt and sandstone pillars placed atop large, circular stone platforms or mounds, often with associated stone circles or cairns. The construction of such sites required the coordination of a considerable amount of labour in order to move hundreds of cubic metres of sediment and to drag heavy stones up to 2km over uneven terrain (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Shea and Grillo2011, Reference Hildebrand2018). Such labour would have been intergenerational, with potentially centuries separating the original builders from those who eventually completed the sites (Hildebrand & Grillo Reference Hildebrand and Grillo2012). As a central feature of early pastoralism around the lake, and now its most enduring legacy, these pillar sites provide a window into the social lives of eastern Africa's first herders and how they coped with a changing world.

Theories regarding who built the pillar sites, and how and why they were constructed, have been strongly shaped by early work at a single site. Jarigole (GbJj1) was the first pillar site to be excavated, resulting in the proposal that pillar sites belong to a previously unknown ‘Jarigole mortuary tradition’. This would have entailed secondary burial—that is, the interment of defleshed, disarticulated remains—within the associated mounds (Nelson Reference Nelson1995). The tradition was assumed to have been imported to the Lake Turkana region by early pastoralists, along with ‘Nderit’ pottery and domestic animals, from some yet-unidentified region to the north. This remained the dominant interpretation of pillar sites for 30 years. Recent excavations, however, have shown that, while other pillar sites were also used as cemeteries by early pastoralists, the observed mortuary practices are strikingly different from the proposed Jarigole mortuary tradition: at these other sites, most individuals are in primary burials—that is, articulated bodies were interred prior to decomposition. At least one site, Lothagam North (GeJi9), is estimated to contain hundreds of individuals within a single, elaborate mortuary cavity (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018). These findings challenge the notion of a single mortuary tradition and raise questions about how potentially diverse social groups maintained connections around and/or across the lake.

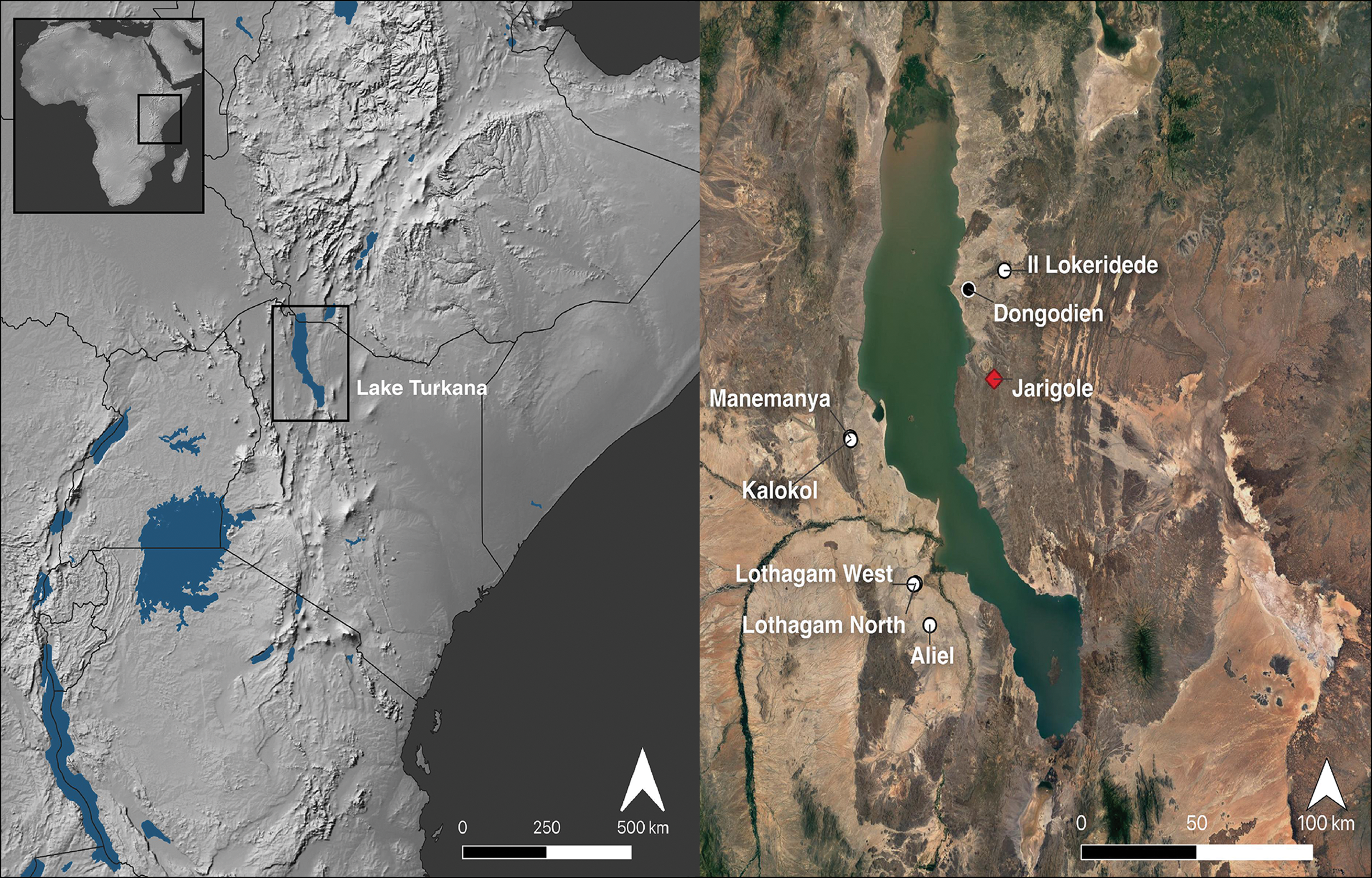

Evaluating the Jarigole mortuary tradition requires us to examine the origins of these sites and burial practices. The earliest dates from excavated contexts (c. 5000 BP) are from the largest pillar sites, Lothagam North and Jarigole. Located on opposite shores of Lake Turkana, these two sites are separated by approximately 100km across the water, or some 300km by land (Figure 1). Many aspects of their material culture, including stone tools, pottery and beads, are remarkably similar (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2019; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019; Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, McKeeby and Hildebrand2022). Substantial differences in construction and mortuary use between them would raise intriguing possibilities for how the practice of building pillar sites began and spread.

Figure 1. Pillar sites around Lake Turkana (red = Jarigole; white = other pillar sites; black = habitation site). Basemap data by Natural Earth (left) and Google (right) (credit: E. Sawchuk).

In this article, we report on new excavations at Jarigole that clarify how the site was constructed and used. In addition, we directly compare Jarigole and Lothagam North to explore the nature and origins of the pillar sites and monumentality in eastern Africa. We evaluate the evidence for the presence of a single pan-Turkana mortuary tradition during this period and present new findings and radiocarbon dates from Jarigole that cast fresh light on the lives of eastern Africa's first herders.

Jarigole in the context of pillar sites around Lake Turkana

The pillar sites were first perceived as possible archaeoastronomical sites, and excavations of other megalithic sites in the Turkana Basin suggested that they might also be burial grounds (reviewed by Hildebrand & Grillo Reference Hildebrand, Grillo, Laporte and Large2022; see also Lynch & Robbins Reference Lynch and Robbins1978, Reference Lynch and Robbins1979; Soper Reference Soper1982). The discovery of isolated human remains at Jarigole and limited excavations at Il Lokeridede (GaJi23; Nelson Reference Nelson1995; Githinji Reference Githinji1999) supported the idea of pillar sites as burial grounds. Since then, additional work at multiple pillar sites has established the chronology of their construction and use between c. 5200 and 4200 cal BP (Hildebrand & Grillo Reference Hildebrand and Grillo2012), explored material cultural and mortuary patterns (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2019; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019; Grillo et al. Reference Grillo2020, Reference Grillo, McKeeby and Hildebrand2022) and documented inter-site variability (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand, Shea and Grillo2011; Grillo & Hildebrand Reference Grillo and Hildebrand2013; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019).

Many original assumptions about the pillar sites have turned out to be true. Initial construction coincided with the introduction of cattle, sheep and goats to the Turkana Basin (Hildebrand & Grillo Reference Hildebrand and Grillo2012; Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018); faunal remains from the contemporaneous Dongodien habitation site suggest that early pastoralists also relied on fish and other wild resources (Marshall et al. Reference Marshall, Stewart and Barthelme1984). The introduction of livestock probably involved some degree of population movement and mixture between migrants and local foragers (Sawchuk Reference Sawchuk2017; Prendergast et al. Reference Prendergast2019). All pillar sites excavated to date are cemeteries, with men, women and children present (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019). Most were interred with some form of personal ornamentation—predominantly beads made from ostrich eggshell and/or stone. Contrary to the idea that these commemorative practices were imported from elsewhere (Nelson Reference Nelson1995), pillar sites appear to be unique to the Turkana Basin, although they are part of a broader trend of mortuary innovation as pastoralism spread from the Sahara into eastern Africa (Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk, Goldstein, Grillo and Hildebrand2018). In northern Africa, earlier examples of monumentality and ritual behaviour among pastoralists, including cattle burials in megalithic stone structures, have been interpreted as possible social responses to climate change and aridification (di Lernia Reference di Lernia2006, Reference di Lernia2013; di Lernia et al. Reference di Lernia2013). While there are no clear connections between Saharan traditions and the pillar sites, the latter may have stemmed, in part, from cultural memories imported with domesticated animals from the north. Why people built pillar sites is perhaps archaeologically unknowable, but communal burial practices may have helped unite dispersed and potentially diverse groups of people, maintaining networks vital for pastoralism around the lake (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk, Goldstein, Grillo and Hildebrand2018). Beyond places of congregation, these burial grounds may have also served as nodes or ‘persistent places’ for mobile pastoralists to anchor and orient themselves as they moved across otherwise fluid landscapes (Lane Reference Lane and Beardsley2016).

Jarigole (GbJj1), the first pillar site to see subsurface exploration, was first studied as part of the Koobi Fora Field School programme between 1986 and 1996, under the direction of Harry Merrick. The site is located on the east side of Lake Turkana, approximately 15km south-east of Alia Bay (3°37′48.0″N, 36°21′36.0″E) (Figure 1). It features an elliptical stone platform, with long axes of approximately 40m (north-west to south-east) and 30m (north-east to south-west), ringed by a partial kerb of cobbles and a roughly circular central mound measuring approximately 25m in diameter and about 1m in height (Figure 2). The Koobi Fora Field School excavations (a 12m × 1–2m trench and four other 1m2 units) reached less than 0.5m below the surface in most units, and never reached bedrock. Thousands of artefacts were recovered from the site, including ceramic sherds and figurines, stone tools, and ostrich eggshell and stone beads, in addition to fragmentary human and animal bone. The discovery of human remains at the site, as well as limited evidence from excavations at Il Lokeridede (GaJi23; Nelson Reference Nelson1995; Githinji Reference Githinji1999), was used to support the hypothesis that these sites were intended primarily for burial purposes. These excavations, however, have remained unpublished, aside from a brief magazine overview (Nelson Reference Nelson1995), a governmental report (Koch Reference Koch1993) and a preliminary paper on ceramic sourcing (Koch et al. Reference Koch, Jerem and Biro2002).

Figure 2. Jarigole as of July 2019. Above) view of the central mound looking north-west; below) view of the site from Jarigole Hill (in the background above), facing north-east (credit: E. Sawchuk).

The Koobi Fora Field School researchers proposed a two-step process for the Jarigole mortuary tradition: primary burial or other treatment off-site, in which bodies were defleshed and disarticulated, followed by secondary burial of fragmentary remains at a pillar site. As evidence, Nelson (Reference Nelson1995) cited the isolated, commingled and disarticulated nature of the human remains scattered throughout the Jarigole mound, which showed no evidence of originating from disturbed primary burials. Material culture scattered throughout the fill deposits of the mound were interpreted as grave offerings, with both human bone and artefacts “mixed into the fill as new burials intruded into and scattered the contents of the old” (Nelson Reference Nelson1995: 52). In one of the final field seasons before Koobi Fora Field School excavations at Jarigole ceased in 1996, one of the deeper units yielded an articulated, flexed skeleton beneath several large rocks, 0.60–0.65m below the surface, in deposits “only just penetrating the lower part of the fill” (Nelson Reference Nelson1995: 52). This prompted questions about whether other rock clusters might conceal primary burials.

Since 2009, excavations at pillar sites to the west of Lake Turkana (Figure 1), especially those at Lothagam North, have changed our understanding of the mortuary behaviours practised at these sites. For example, whereas Nelson (Reference Nelson1995) interpreted Jarigole's mound as the initial construction, with burials subsequently dug into it, Lothagam North's construction began with the removal of 120m2 of sand to create a deep cavity reinforced by a perimeter of sandstone slabs. Initially, people placed bodies in pits dug into the soft sandstone bedrock at the base of the cavity; over time, people added numerous additional burials in various positions and orientations, often placing large rocks atop heads and/or torsos. Before the space was exhausted, people capped the cavity with sediment containing broken pottery, other artefacts and isolated human remains, creating a low mound. The 2012–2014 excavations recovered evidence for a minimum of 44 men, women and children. The density of excavated burials, coupled with estimates of the cavity's dimensions from ground-penetrating radar survey, suggests at least 580 individuals were interred at the site (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019).

The uppermost deposits at both Lothagam North and Jarigole have yielded similar material: isolated, fragmentary human remains and various artefacts. The in-situ interments at Lothagam North, however, were all discovered more than 0.6m below the surface, in the mortuary cavity. Two thirds of the burials were primary, indicating that individuals were brought to the site and buried soon after death; others were secondary ‘bundle burials’, or too poorly preserved to assess. The results from Lothagam North therefore raised the possibility that the original excavations at Jarigole, which do not appear to have extended more than 0.5m below the ground surface in most units, may have stopped short of any deeper, primary inhumations, and consequently that site formation and mortuary practices at these two pillar sites do not, in fact, differ substantially.

New findings from Jarigole

In July 2019, we commenced new fieldwork at Jarigole to test the hypothesis that deeper excavations would reveal a mortuary cavity and primary burials. We removed backfill from a 7 × 1m section of the Koobi Fora Field School trench to expose the stratigraphy and deepen the excavations in the southernmost 2 × 1m. An additional 2 × 1m section was reopened in the centre of the mound, and a new 2 × 1m trench placed adjacent. Although our deepest excavations reached 1.6m below the surface in the centre of the mound, we still did not find sterile substrate or bedrock. Two previously excavated 1 × 1m units and a new 0.5 × 0.5m unit were opened to revisit the stratigraphy and provide context for the stone platform construction (Figure 3). Excavation methods followed protocols from other pillar sites (Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019) and the finds are curated with the earlier Jarigole collection at the Nairobi National Museum.

Figure 3. Jarigole site plan, indicating Koobi Fora Field School (KFFS) and new excavation areas (credit: D. Contreras).

Our findings demonstrate that Jarigole's construction began with the excavation of a planned mortuary cavity and the building of a surrounding circular stone platform. This platform consists of a series of short, basalt cobble retaining walls with rubble filling the spaces between them (Figure 4). Toward the centre, this platform terminates abruptly at a large, central mortuary cavity extending more than 1.6m below the current mound surface. Unlike at Lothagam North, where the cavity was dug into loose sand that had to be held in place by large, tilted sandstone slabs, the compacted sterile substrate at Jarigole appears to have held firm without need for reinforcement.

Figure 4. Eastern profiles of 2019 excavations (credit: A.C. Hill).

In-situ articulated burials were found at Jarigole more than 1.1m below the top of the mound surface—deeper than any of the excavations carried out by the Koobi Fora Field School. Above the burials, the deposits were consistent with what has been previously recorded, containing only fragmentary, isolated remains, of which the majority are small elements, such as teeth and phalanges. Below, six burial features, marked by large rocks, contained the remains of at least nine individuals (Table 1). Burials 1–3 were found in closely spaced pits on the northern perimeter of the mortuary cavity (Figure 5), beginning at approximately 1.1m below the current ground surface. Burials 4–6 were recovered from the centre of the mound at approximately the same depth—around 1.15m below the surface. All of the individuals were flexed, primary burials and variously orientated, with the exception of Burial 5, which consisted of at least three (based on crania) commingled, disarticulated individuals. Whether this specific feature represents an intentional secondary burial or the presence of one or more primary burials that had been disturbed by the interment of Burial 6, which is located immediately below, is unclear. None of the other burials appear to have been disturbed. Isolated skeletal elements from features visible in the trench profiles were also recovered, indicating dense burial deposits. Among the total assemblage of recovered human remains, adults of both sexes, as well as juveniles, are represented.

Figure 5. Burial 3 in a pit at the northern edge of the mortuary cavity. Burials 1–2 were recovered from pits in the background (credit: E. Sawchuk).

Table 1. Bioarchaeological context for burials excavated in 2019 (Ad = adult; YAd = young adult; MAd = middle-aged adult; M? = probable male; F? = probable female; ? = undetermined sex).

As with the previous excavations, artefacts, as well as isolated human and animal remains, were found scattered throughout the deposits. Finds include ostrich eggshell and stone (predominantly amazonite) beads, lithics, broken Nderit vessels, ceramic animal figurines (Figure 6a), and fragments of ochre and charcoal. The Nderit ceramic assemblage includes a striking phallic bottle neck—the first of its kind to be found in eastern Africa (Figure 6b). Artefact types and densities were similar in the cap deposits and infill deposits below, with additional beads from jewellery or garments worn by deceased individuals recovered from the burials in lower levels. Most individuals were associated with some form of ornamentation (Table 1). The individual in Burial 4 was found with more than 100 amazonite and other stone beads near their neck and chest, which were perhaps worn as a necklace (Figure 7). Over 300 small (approximately 3mm in diameter) ostrich eggshell beads, which encircled the right radius/ulna of the individual in Burial 6, appear to be a bracelet. Other ornaments include over 4000 ostrich eggshell beads both associated with burial features and scattered throughout the cavity.

Figure 6. New ceramic finds from Jarigole: a) animal figurine; b) fragment of phallus-shaped ceramic bottle found near the Burial 4 individual (credit: K. Grillo).

Figure 7. Amazonite and other stone beads found near the neck of the Burial 4 individual (original layout for necklace is unknown) (credit: K. Grillo and E. Hildebrand).

Dating the deposition of both burials and fill at Jarigole, as well as at other pillar sites in the Turkana Basin, is challenging, given the risks of inbuilt age in the available dateable materials. Ostrich eggshell beads may be made from old material and may have circulated before being buried; charcoal is likely to have a smaller offset but may still incorporate both old wood and residence time effects. Radiocarbon dates on these materials provide termini post quem rather than dates of deposition, however, as it is unlikely that every sample has an age offset, much less the same one. As dates on charcoal should more closely approximate date of deposition than those on ostrich eggshell beads, a single-phase Bayesian model incorporates the new dates on both charcoal and ostrich eggshell, which captures the span during which Jarigole was likely in use (Table 2; Figure 8). Because no chronological data are available that can constrain the beginning of the phase, the model potentially overestimates the age of the earliest deposits at Jarigole; this might be addressed in future through outlier modelling (e.g. Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009b). This tendency to overestimate the duration of use is perhaps balanced by the fact that the model obviously cannot account for any earlier deposits that remain unexcavated. While these uncertainties remain, this approach to the radiocarbon evidence suggests a period of use that is relatively short, from 4940 to 4630 BP (95% range of phase kernel density estimate: Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017). This is consistent with the radiocarbon evidence from Lothagam North (4920–4650 BP at 95% range of phase kernel density estimate), suggesting that both cemeteries were in use for approximately three centuries at the beginning of the fifth millennium BP. A single outlier from Lothagam North, which was excluded from analysis, may suggest a subsequent phase of use approximately three centuries later. This would be consistent with similar dates from the pillar sites at Kalokol and Manemanya (Figure 8; see also the online supplementary material (OSM)).

Figure 8. Radiocarbon dates from Jarigole (Table 2) and other pillar sites (see the online supplementary material (OSM)). All dates are from excavated contexts, except Aliel. Modelled in OxCal 4.4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a, Reference Bronk Ramsey2021) using a mixed curve (following Marsh et al. Reference Marsh2018) that incorporates the uncertainty of not knowing the appropriate mixture of IntCal20 and SHCal 20 (Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020) in locations near the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). Jarigole and Lothagam North are modelled as independent phases, with available radiocarbon dates from other pillar sites included (unmodeled) for comparison. Brackets at left indicate model structure; with the single late date (ISGS-A3792) from Lothagam North excluded as an outlier (indicated in light grey), the dates are consistent with the model parameters (Amodel = 115). The kernel density estimate plots of each phase (in blue) summarise the posterior distributions of the modelled dates in each phase to produce estimates of the span of each phase (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2017) (credit: D. Contreras).

Table 2. Radiocarbon dates from Jarigole. Dates from Koobi Fora Field School excavations have been adapted into the 2019 excavation unit numbering system; based on available field notes, the Koobi Fora Field School datum is thought to be at/close to the excavation surface. All dates were calibrated in OxCal v4.4.2 with a mixed IntCal20 and SHCal20 calibration curve (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009a; Hogg et al. Reference Hogg2020) per Marsh et al. (Reference Marsh2018) and rounded to the nearest five years.

Discussion

The similarity in the mortuary cavities at Jarigole and Lothagam North indicates that the people who constructed these sites followed a predetermined plan that began with a significant investment of labour to excavate a large area for burial. Coordination is evident in the sites’ parallel use, which encompassed placement of the deepest burials in pits (at least on the cavity's periphery at Jarigole), followed by interment of mostly articulated, as well as some disarticulated, individuals in various positions and orientations, typically marked with large rocks. Then, at some point before the cavities were entirely filled with burials, at both sites, the remaining space in the cavities was filled with sediment containing a mixture of beads, broken pots and human remains (among other material), and capped by circular platforms featuring low mounds and pillars.

While Jarigole is therefore no longer an outlier from the regional tradition, there are still notable differences compared with Lothagam North. The cap deposits at Jarigole are nearly twice as deep, which explains the original excavators’ interpretation that it was a secondary burial ground. This raises the question of whether Jarigole's use as a primary burial site was intentionally less intensive and/or endured for a shorter duration than at Lothagam North, resulting in more of the cavity being filled with sediment when the burial cavity was capped. Another key difference is found in the ceramic figurines, which are relatively common at Jarigole (Hildebrand et al. Reference Hildebrand2018: fig. S2) but absent at every other pillar site excavated to date. This exemplifies the presence of inter-site variability that seems deliberate and meaningful, such as site-specific preferences for different types of stone for beads (Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019). Given the scope of this tradition across time and space, some of this variation possibly reflects differences between the local communities who created and used these cemeteries. It is also possible that the sites were used by multiple groups with diverse origins, identities and/or material practices.

Intriguing questions therefore remain concerning when and how individual pillar sites were capped. From where did the sediments for the cap deposits originate, and why do they contain so many artefacts and human remains? At both Jarigole and Lothagam North, thousands of ostrich eggshell beads, hundreds of Nderit sherds (seemingly from deliberately broken pots), and other artefacts are present throughout the cap fills, as though they were intentionally brought to the site and scattered (Nelson Reference Nelson1995; Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019; Grillo et al. Reference Grillo, McKeeby and Hildebrand2022). Isolated human remains are similarly frequent—especially teeth and hand bones.

There are several possible scenarios for how these pillar sites were completed. First, the mortuary cavities might have previously contained more burials, with the upper interments being removed during the capping process, resulting in their remnants becoming incorporated into the fill. This seems unlikely (albeit not impossible), given how dense and fragmentary the in-situ burials are at lower depths and how few isolated remains are present in the cap deposits; any removal would thus have had to have been very thorough. Second, carnivores could have disturbed the upper layers. This is unlikely, given the absence of gnaw marks and the low density of remains and types of skeletal elements present. Third, sediment for the cap deposits could have been sourced from nearby cemeteries, habitation sites and/or middens. This too seems unlikely, as no such sites have been found near either Jarigole or Lothagam North, the density of Nderit sherds and ostrich eggshell beads is relatively consistent throughout the platforms, and larger elements are absent among the isolated human remains. A fourth scenario, which seems to be the most parsimonious, is that people brought artefacts and isolated human remains to pillar sites and scattered these elements as part of a mortuary ritual, and that this practice continued after primary burial ceased, as the remaining cavity was being filled. If this suggestion is accurate, then the original interpretations of the Jarigole mortuary tradition were, to a degree, correct: parts of individuals who died elsewhere were routinely mixed into the fill, along with broken pots, beads and other offerings, potentially during and after the phases in which Jarigole was used for primary burial (see also Lane Reference Lane and Beardsley2016).

The new evidence from Jarigole prompts a reconsideration of how herders organised themselves across this landscape, and how death and burial impacted everyday life. Nelson (Reference Nelson1995) reasoned that pastoralists who ranged over several hundreds of kilometres might choose to inter expediently and/or prepare the dead elsewhere, and then bring their remains to a pillar site at certain points in the seasonal cycle. While this may have been true during some of Jarigole's period of use, the prevalence of primary, in-situ burials during the early stages of use demonstrates that many individuals were brought to the site and interred shortly after death. Groups must have been within a few days’ walk from a pillar site to enable these burials, and/or funerary rituals were important enough for people to cease other activities and travel whenever a death occurred. It is impossible to distinguish between such possibilities without a better understanding of early herder mobility around the lake, which is difficult to reconstruct, given that most of our available information originates from these mortuary sites. Even if communities remained relatively close to the lakeshore, Turkana's shorelines shifted over time. In addition, we do not know whether funerals were large gatherings or smaller affairs, why individuals were interred in primary vs secondary burials (or perhaps scattered in the mortuary fill), nor whether inclusion at a specific site was based on place of birth or death, or other determinants (Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019). Future research on individuals and isolated remains excavated from different pillar sites using isotopic and ancient DNA analyses will be critical for interrogating both mortuary and mobility patterns among these pastoralist groups and for reconstructing aspects of their lives from their treatment in death.

Conclusions

The original concept of a Jarigole mortuary tradition, which had already been revised based on evidence from the western pillar sites (Sawchuk et al. Reference Sawchuk2019), can now be completely overhauled. The relative consistency of site formation processes at both Jarigole and Lothagam North, along with evidence that they were constructed and used contemporaneously, suggests that pillar sites do indeed represent a unified mortuary tradition that was developed in and practised throughout the Turkana Basin. Contrary to initial interpretations, however, this primarily involved the transport of the deceased to pillar sites for burial soon after death. Future research aimed at reconstructing patterns of individual and group mobility from the remains of individuals buried at these sites will be instrumental in untangling the interconnected social landscapes that extended across the Turkana Basin at a time of profound environmental and economic upheaval. Understanding the origins of pillar sites not only speaks to the context in which pastoralism began in eastern Africa, but also the diverse ways in which these societies responded to change with innovation that united the living through interring the dead. This case study likewise serves as an important comparative reference for the growing archaeological literature on pastoralist mortuary practices (e.g. Doumani et al. Reference Doumani2015; Núñez et al. Reference Núñez2017; Jaffe Reference Jaffe2020) and their social significance worldwide.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Museums of Kenya and the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (NACOSTI) for permission to study Jarigole. We also thank Kenya Wildlife Services and the rangers at Sibiloi National Park, as well the 2019 Koobi Fora Field School. We are grateful to Jarigole's previous excavators, Christopher Koch and Charles Nelson, for providing advice and unpublished data.

Funding statement

Funding for this research was provided by the Wenner-Gren Foundation (grant 9745 to EAS), the National Geographic Society (NGS-61788R-19 to EAS) and the Turkana Basin Institute, with the latter also providing logistical support. During this work, EAS was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC 756-2017-0453 and BPF 169449).

Supplementary materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2022.141.