Introduction

A little more than a decade ago, A Companion to Greek Art, inspired by similar edited volumes concerned with modern art, was conceived in an effort to bring a variety of old and new voices to the field (Smith and Plantzos Reference Smith and Plantzos2012). For its purposes, ‘Greek art’ was widely construed to include architecture, colonization, and reception, and the book was reissued in paperback in 2018 with corrections and an updated bibliography. Since that time, other companions and handbooks – notably those edited by Clemente Marconi on Greek and Roman art and architecture (Reference Marconi2014), with a recommended section on ‘approaches’, and by Margaret Miles on Greek architecture (Reference Miles2016), which includes temple decoration – have found a home on the bookshelves of student and scholar alike; and a place for Greek art and all it entails was established alongside no shortage of such volumes devoted to many aspects and periods of the ancient Mediterranean world. Simultaneously, a spate of introductory textbooks in English, most commissioned by their publishers, began to take shape in a feverish attempt to bring Greek art (often coupled with ‘archaeology’) up to date for a student audience through the incorporation of new finds and photographs, and importantly fresh perspectives (Neer Reference Neer2011/2018; Maffre Reference Maffre2013, in French; Barringer Reference Barringer2015; Stansbury-O’Donnell Reference Stansbury-O’Donnell2015; Plantzos Reference Plantzos2016, translated from the Greek original of 2011).

While each of these books continues to play a role in the general presentation of Greek art, a field still bound by chronology and canon, the focus in what follows is on more recent developments and trends, as well as on the space and place of Greek art as it relates to Classical studies, Mediterranean archaeology, and to an extent the history of art (Map 8.1). For our purposes, Greek art incorporates the visual imagery and material objects, both small and large, recovered from the past and, as such, situated within the broader field of Classical archaeology. Given the large number of publications that cover only the past five to six years, among them single-authored monographs, edited volumes, site reports, and journal articles, this summary of the literature will primarily be drawn on books from that period, and occasionally journal articles or earlier works considered to be of particular merit or importance. Examples are chosen to span the long Archaic to Hellenistic phases (eighth–first century BC). A full range of artistic categories and media are included in the many publications cited, among them sculpture, vases, terracottas, painting, mosaic, and metals. Architecture is largely excluded, and the recent feature on it in Archaeological Reports covers current bibliography of relevance, especially pertaining to sanctuaries as an ancient setting and archaeological context for art across the Greek world (Sapirstein Reference Sapirstein2023, 175–77).

General, surveys, reference

In addition to the books already mentioned, general introductions that serve students and the public continue to be generated. A traditional staple, John Boardman’s Greek Art was updated a fifth time in Reference Boardman2016, 50 years after its original publication. Along with his handbooks on vases and sculpture, it continues to be made available in many languages. A third edition of Tonio Hölsher’s Die griechische Kunst appeared in Reference Hölsher2022, as well as two handbooks for university students in Italian (Lippolis and Rocco Reference Lippolis and Rocco2020; Bejor, Castoldi and Lambrugo Reference Bejor, Castoldi and Lambrugo2021, updated edition) and the posthumous writings of Phillippe Bruneau, Propos sur l’art grec, based on a series of courses for students (Balut and Brun-Kyriakidis Reference Balut and Brun-Kyriakidis2017). Also intended for a general readership, the new edition of Thomas Carpenter’s Art and Myth in Ancient Greece (Reference Carpenter2021) is now illustrated almost entirely in colour and as such is friendlier on the eyes. While issues of style are no longer au courant, William Childs’ detailed and erudite tome on the fourth century BC (Reference Childs2018) fills a much-needed gap and helps to question both past and existing systems of chronology, terminology, and framing (e.g. where does the Late Classical end and Hellenistic begin?). A rather different tactic is taken by Kristen Seaman (Reference Seaman2020), who uses three well-known, if less-representative, works of Hellenistic art as case studies to explore connections between rhetorical techniques, education, and artistic innovation. Though by no means an introduction to Hellenistic art, it is an accessible account that addresses through interdisciplinary means many of the concerns raised in the late Andrew Stewart’s thematically-driven Art in the Hellenistic World (Reference Stewart2014).

Greek art also continues, both directly and indirectly, to find its way into handbooks and companions that address a wide variety of topics. Such chapters make excellent starting points for further exploration and provide useful bibliography. Singled out for mention, given their clarity and coverage, are: Alistair Harden’s essay on ‘Animals in Classical art’ (Reference Harden and Campbell2014); Milette Gaifman’s questioning of ‘Visual evidence’ for ancient religion (Reference Gaifman, Eidinow and Kindt2015); Olympia Bobou’s ‘Representations of children in ancient Greece’ (Reference Bobou, Crawford, Hadley and Shepherd2018); Sheramy Bundrick’s ‘Visualizing music’ (Reference Bundrick, Lynch and Rocconi2020); Hariclia Brecoulaki’s inspiring piece on ‘Greek interior decoration’ (Reference Brecoulaki and Irby2016/2020); and Olga Palagia’s ‘The iconography of war’ (Reference Palagia, Heckel, Naiden, Garvin and Vanderspoel2021). Not surprisingly, Greek art and material culture are woven throughout The Cambridge Companion to Ancient Athens (Neils and Rogers Reference Neils and Rogers2021), with dedicated chapters on coins, pottery, and sculpture. Also helpful to consult are volumes in ‘cultural history’ series (such as Bloomsbury’s), which incorporate Greek art in a variety of often unexpected ways and through such timely themes as the senses (Bradley Reference Bradley and Toner2014/2019), race and gender (Haley Reference Haley and McCoskey2022), and objects (Osborne Reference Osborne2022). Similarly, the edited volumes in ‘The Senses in Antiquity’, a series produced by Routledge in recent years, includes Greek art variously treated: for example, Grethlein (Reference Grethlein and Squire2016) on sight and vases; Turner (Reference Turner and Squire2016) on sight and death; Platt and Squire (Reference Platt, Squire and Purves2017) on haptics. While bringing the discipline in line with subjects already well treated by art historians and anthropologists, some of these authors are arguably more approachable for beginners than others. Much of relevance to our discipline is to be found in the substantial Dictionnaire du corps dans l’Antiquité (Bodiou and Mehl Reference Bodiou and Mehl2019), a reference resource that both promises and delivers. Although something of a mixed bag, Oxford Bibliographies online may also be recommended for references to date on many subjects (e.g. Greek art, sculpture, numismatics), the most recent being the entry on Greek vase-painting (Smith Reference Smith2019).

Sites, reports, guides

The presentation of primary archaeological finds deriving from archaeological sites remains a vital resource in the study of Greek art. Large-scale excavations in Greece, such as those at the Heraion of Samos (ID18179, ID17978) directed by the DAI and those at the Athenian Agora (ID18538, ID18405) under the auspices of the ASCSA, have provided carefully studied and well-dated bodies of material, and offer new content, proper context, and points of comparison for many categories of Greek art. Outside of Greece, substantial sites in Sicily (e.g. Morgantina), south Italy (e.g. Metapontum), and Turkey (e.g. Miletus) have been similarly treated in the past and their series continue (Bottini et al. Reference Bottini, Graells i Fabrigat and Vullo2019; Schaus Reference Schaus2021, Laconian and Chian pottery; Bell Reference Bell2022) or have been launched anew (e.g. Rose, Lynch and Cohen Reference Rose, Lynch and Cohen2019, Iron Age-Classical Troy). Site report volumes, often covering a single artefact type, medium, or chronological period, continue to appear in traditional print format, though increasingly with full or partial digital access options. Regardless, with the right amount of patient looking, they should be viewed as a fundamental (if somewhat underutilized) source of new examples as well as opportunities to review and reevaluate existing narratives about sites and regions, and their visual and material culture.

Several site-based volumes devoted to sculpture, and particularly beneficial to the study of Greek art, have appeared recently: the Gymnasium area at Corinth (Sturgeon Reference Sturgeon2022); the corpus of over 2,000 published and unpublished fragments from Delphi (Martinez Reference Martinez2021a); ‘heroic’ reliefs from Thasos (Holtzmann Reference Holtzmann2018); votive and honorific monuments at Delos (Herbin Reference Herbin2019); and votive reliefs from the Athenian Agora (Lawton Reference Lawton2017). Other recent contributions to note present other types of evidence and would include one on Hellenistic fine ware pottery from Corinth (James Reference James2018), another from the same site on terracotta finds (Klinger Reference Klinger2021), Late Classical and Hellenistic pottery from Isthmia (Hayes and Slane Reference Hayes and Slane2021), decorated pottery and other finds from Methone (Morris and Papadopoulos Reference Morris and Papadopoulos2023), and bronzes at Delphi (Aurigny Reference Aurigny2019). Several additional publications, like those mentioned from Sicily and south Italy above, include archaeological materials applicable to Greek art (e.g. figure-decorated pottery, coins, metals, terracottas), in various states of preservation, embedded in broader discussions of a site’s occupation phases (e.g. Gex Reference Gex2019, Classical and Hellenistic finds from Eretria), or a specific area or campaign (e.g. Bravo and MacKinnon Reference Bravo and MacKinnon2018, Shrine of Opheltes at Nemea; Touchais and Fachard Reference Touchais and Fachard2022, Aspis at Argos). The ongoing Naukratis project based at the British Museum has gathered the excavated finds (over 17,000 objects distributed among more than 70 locations) into an online research catalogue, offering us an inspiring model for digital-born site reports going forward (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/projects/naukratis-greeks-egypt).

New guidebooks continue to appear for both sites and museums in Greece and remain useful especially for their updated, high-quality illustrations. The new guide to Delphi and its museum (Valavanis Reference Valavanis2018), published in Greek, English, and French, is a concise introduction to the monuments and finds on display; while a nicely produced guide to Messene (Themelis Reference Themelis2018) is available in both Greek and English. Of particular note are a new guide to the Archaeological Museum of Patras (Kolonas and Stavropoulou-Gatsi Reference Kolonas and Stavropoulou-Gatsi2017), one to the Archaeological Museum of Drama (Papadopoulos Reference Papadopoulos2019), another coinciding with the opening of the Archaeological Museum of Chalkis (Simosi Reference Simosi2022), and a special volume to mark the 60-year anniversary of the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki (Koukouvou and Ziogana Reference Koukouvou and Ziogana2022). The late Stephen Miller’s edited guide to the site and museum of Nemea has been reissued following his death in 2021 (Miller Reference Miller2022), and his two-volume personal account of several decades’ work at the site is equally valuable for its broader look at the region and the construction of the archaeological museum and its holdings (Miller Reference Miller2020). The recent presentation of the local and imported sculpture from Agrigento, both free-standing and architectural, straddles the line between site report and museum guide, and grants both detail and overview from a voice highly familiar with the site itself and the phenomenon of Greek art and material culture in Sicily in general (De Miro Reference De Miro2021a; cf. De Miro Reference De Miro2023). Iconography and offerings are treated by several authors in an edited volume focused on cult and representation of Artemis in the context of sanctuaries of Apollo, a clever and comparative way to approach art/artefact and one that foregrounds archaeological context (Aurigny Reference Aurigny2021).

Exhibitions, conferences, Festschriften

Despite the limitations of the COVID pandemic, there has been no shortage of exhibitions engaging Greek art. The ones underscored here have generated published catalogues and represent an impressive range of themes that perhaps indicate the best of all the true ‘state of the field’. Three ‘emerging cities’ in Crete were highlighted at the Museum of Cycladic Art in 2018–2019, which featured some 500 artefacts, among them statues, reliefs, and jewellery, dating from the Neolithic to the Byzantine periods, with an accompanying catalogue published in Greek and English (Stampolidis et al. Reference Stampolidis, Papadopoulou, Lourentzatou and Fappas2020). Classical art situated in relation to the wider ancient worlds of Egypt and Persia framed two exhibitions organized at the Getty, each showcasing artistic and cultural interplay and resulting in lavishly illustrated catalogues (Spier, Potts and Cole Reference Spier, Potts and Cole2018; Reference Spier, Potts and Cole2022). The proceedings of the scholarly symposium coinciding with one of them also appeared in 2022 and is available in print or via Open Access under the title Egypt and the Classical World: Cross-Cultural Encounters in Antiquity (Spier and Cole Reference Spier and Cole2022; https://www.getty.edu/publications/egypt-classical-world). In keeping with growing interest in animals in antiquity, the exhibition at Harvard on animal-shaped vessels understood in relation to feasting practices resulted in a beautifully produced catalogue gathering evidence from prehistoric Greece to medieval China (Ebbinghaus Reference Ebbinghaus2018). Concerned exclusively with the horse in Greek art and culture were exhibitions in Virginia and Athens, the former with a few general essays (Shertz and Stribling Reference Shertz and Stribling2017), the latter presenting a bilingual series of mini-essays dedicated to individual examples (Neils and Dunn Reference Neils and Dunn2022). More restricted in scope have been exhibitions based on artefact type including: terracotta figurines from Thrace and Macedonia and the iconography of Greek coins, each published in both Greek and English (Adam-Veleni, Koukouvou and Palli Reference Adam-Veleni, Koukouvou, Palli, Stefani and Zografou2017; Stampolidis, Tsangari and Tassoulas Reference Stampolidis, Tsangari and Tassoulas2017); realism in Greek sculpture (Nowak and Winkler-Horacek Reference Nowak and Winkler-Horacek2018); and vases in the oeuvre of the Berlin Painter (Padgett Reference Padgett2017) and in France from the collections in Marseilles and at the Bibliothèque nationale (Détrez Reference Détrez2020).

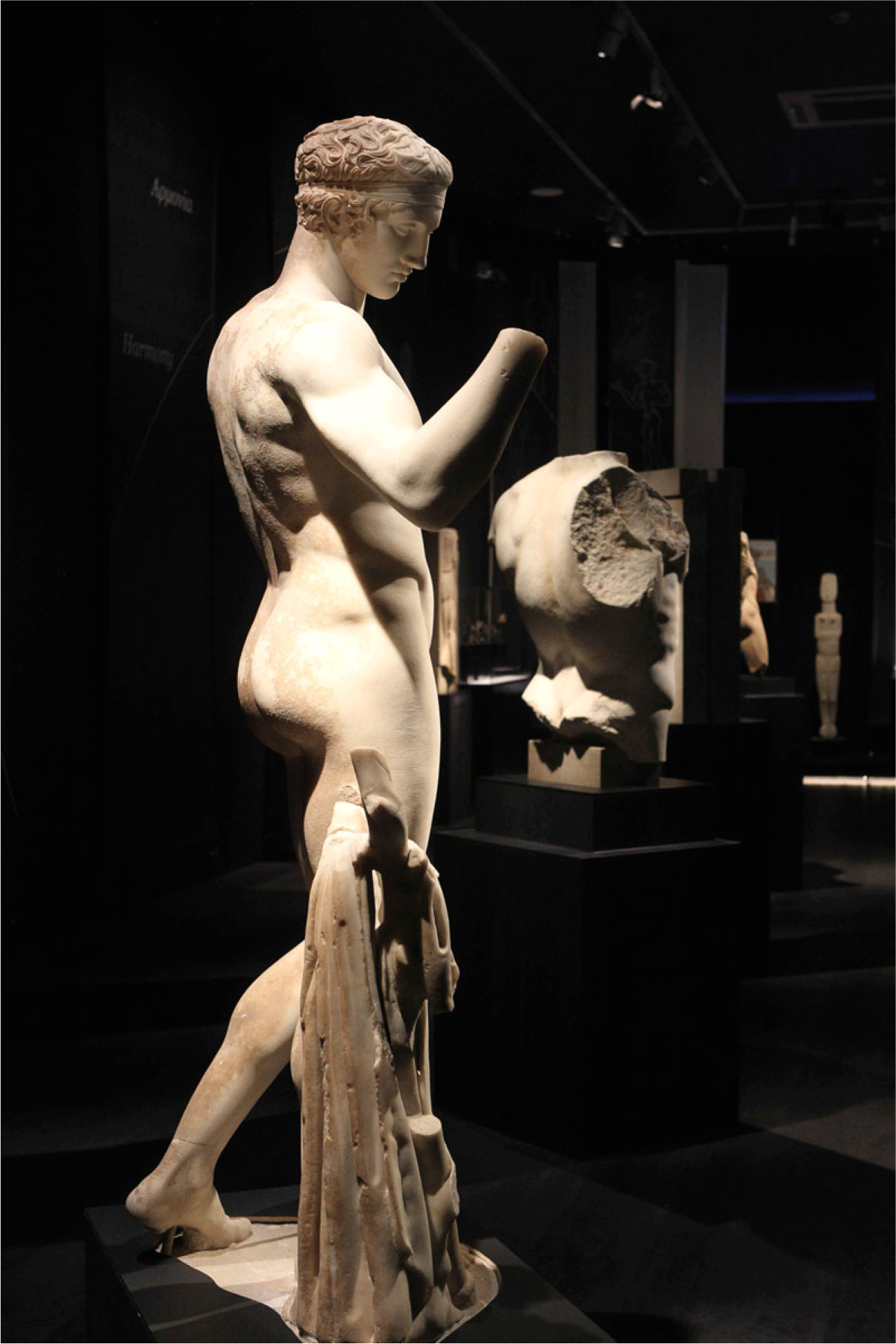

Other exhibitions chose themes that approach the experience and meaning of Greek art and materiality. Several have drawn on timeless concerns, such as two held in Athens on beauty (Fig. 8.1), both published in Greek and English, and both incorporating major stylistic periods and various artistic categories (Lagogianni-Georgakarakos Reference Lagogianni-Georgakarakos2018; Stampolidis and Fappas Reference Stampolidis and Fappas2021); two on death and the afterlife, including one organized a few years ago by the Museum of Cycladic Art and the Onassis Foundation (Stampolidis and Oikonomou Reference Stampolidis and Oikonomou2014) and the other held more recently at the Getty dedicated to the these topics in South Italian vase-painting (Saunders Reference Saunders2021). In keeping with newer trends in both Classics and later historical periods was the landmark exhibition A World of Emotions, which showed at the Onassis Cultural Center in New York and also at the Acropolis Museum (Chaniotis, Kaltsas and Mylonopoulos Reference Chaniotis, Kaltsas and Mylonopoulos2017; cf. Räuchle, Page and Goldbeck Reference Räuchle, Page and Goldbeck2022). Another exhibition, Klangbilder: Musik im antiken Griechenland, held at the Antikensammlung der Staatlichen Museen in Berlin, similarly emphasized the human experience of music using vases, figurines, sculpture, and a modern kithara replica (Schwarzmaier and Zimmermann-Elseify Reference Schwarzmaier and Zimmermann-Elseify2021). The polychrome reconstructions of ancient Greek sculptures, such as the Riace Bronzes and the archer from the temple of Aphaia on Aegina, have by now been exhibited in many countries, and have played no small role in altering modern perceptions by downplaying the ‘myth of whiteness’ (Brinkmann, Dreyfus and Koch-Brinkmann Reference Brinkmann, Dreyfus and Koch-Brinkmann2017).

Map 8.1. 1. Samos; 2. Athens; 3. Morgantina; 4. Metapontum; 5. Miletus; 6. Troy; 7. Corinth; 8. Delphi; 9. Thasos; 10. Delos; 11. Isthmia; 12. Methone; 13. Eretria; 14. Nemea; 15. Argos; 16. Naukratis; 17. Messene; 18. Patras; 19. Drama; 20. Chalkis; 21. Thessaloniki; 22. Agrigento; 23. Aphaia; 24. Thermopylae; 25. Salamis; 26. Rhodes; 27. Argilos; 28. Alexandria; 29. Sounion; 30. Bassai; 31. Olympia.

Several exhibitions engage with myth or history, or both. Interestingly, those concerned with mythological subjects have been based outside of Greece. These would include two Italian exhibitions in Turin and Tivoli, devoted to Herakles and Niobe, respectively, and their reception in later works of Italian art (Von Hase Reference Von Hase2018; Bruciati and Angle Reference Bruciati and Angle2023), and one in Germany on Dionysos in Classical antiquity and beyond, housed at the Saxony-Anhalt Wine Museum at Neuenburg Castle in Freyburg (Philipsen, Lehmann and Hanisch Reference Philipsen, Lehmann and Hanisch2018). The Olympian gods were the subject of an exhibition of the Dresden sculpture collection at the Museum Barberini (Knoll and Wetzig with Philipp Reference Knoll, Wetzig and Philipp2018), and of another in Reggio Calabria (Malacrino, Di Cesare and Marginesu Reference Malacrino, Di Cesare and Marginesu2019). Bridging myth and history was the exhibition on Troy at the British Museum (Villing et al. Reference Villing, Fitton, Donnellan and Shapland2019), which featured everything from the famous Achilles and Penthesilea vase by Exekias of ca 530 BC, to Sydney Hodges’ 1877 portrait of Heinrich Schliemann and a 1970s collage by African-American artist Romare Bearden. Commemorating the 2,500th anniversary of the Battle of Thermopylae and the naval battle of Salamis was Glorious Victories. Between Myth and History / Οι Μεγάλες Νίκες. Στ Όρι του Μύθου κι της Ιστορίς at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, displaying carefully selected objects (e.g. the bust of Themistocles from Ostia) and a catalogue with essays (Lagogianni-Georgakarakos Reference Lagogianni-Georgakarakos2020). The 200-year anniversary of the Greek War of Independence occasioned landmark exhibitions and cultural events, both in Greece and elsewhere (Lagogianni-Georgakarakos and Koutsogiannis Reference Lagogianni-Georgakarakos2020; Betite and Wurmser Reference Betite and Wurmser2021; Lefèvre-Novaro Reference Lefèvre-Novaro2021; Martinez Reference Martinez2021b). Further connecting antiquity to modernity, and enlisting Greek art in diverse and creative ways, were exhibitions such as The Classical Now at King’s College London (Squire, Cahill and Allen Reference Squire, Cahill and Allen2018); Picasso and Antiquity at the Museum of Cycladic Art (Stampolidis and Berggruen Reference Stampolidis and Berggruen2019); Peter and Pan: From Ancient Greece to Neverland at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (Kreinin Reference Kreinin2019); L’istante e l’eternità. Tra noi e gli antichi installed at the Baths of Diocletian in Rome (Verger, Osanna and Catoni Reference Verger, Osanna and Catoni2023); and Freud’s Antiquity: Object, Idea, Desire at the Freud Museum in London, accompanied by a printed catalogue and Open Access digital archive (Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Leonard, Orrells, DeRose and Heller2023; https://stories.freud.org.uk/freuds-antiquity-object-idea-desire/).

Some important conference volumes have appeared in the period of this review, though arguably less than usual due to delays in publication. Two conferences on Greek art in general, one held in Edinburgh in 2017 and dedicated to the memory of François Lissarrague who co-organized the event, and the other held at the ASCSA looking specifically at architecture, sculpture, and vase-painting in Athens during the second half of the fifth century, bring to light a range of subjects and approaches (Barringer and Lissarrague Reference Barringer and Lissarrague2022; Neils and Palagia Reference Neils and Palagia2022). A conference investigating the seventh century was held at the BSA in 2011 and its proceedings include no shortage of essays of relevance here (Charalambidou and Morgan Reference Charalambidou and Morgan2017). The occasion of John Boardman’s 90th birthday was marked with an international congress in Lisbon, resulting unsurprisingly in a substantial publication mirroring his own wide-ranging contributions to the field (i.e. pottery, gems, trade, colonization, etc.) (Morais et al. Reference Morais, Leão, Pérez and Ferreira2019; Fig. 8.2); these are articulated in Boardman’s own words in his autobiography of Reference Boardman2020. Singled out for mention is New Approaches to Ancient Material Culture in the Greek and Roman World. Originating as a conference in Winnipeg, this interdisciplinary volume updates and expands our thinking through themes such as context, interconnection, experiment, and technology (Cooper Reference Cooper2020).

8.1. Diadoumenos on display, Countless Aspects of Beauty in Ancient Art exhibition at the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, 2018. © Greek Photo News /Alamy Stock Photo.

8.2. Cover of Greek Art in Motion: Studies in Honour of Sir John Boardman on the Occasion of his 90th Birthday. © Rui Morais, Delfin Leão, and Diana Rodríguez Pérez.

Another two events, held in Volos and Thessaloniki and concerned exclusively with ceramics (i.e. trade, iconography, workshops), contain in their corresponding volumes papers on Attic finds in Thessaly (Manakidou and Avramidou Reference Manakidou and Avramidou2019) and locally and imported wares in the Northern Aegean (Katakouta and Palaiothodoros Reference Katakouta and Palaiothodoros2023). Proceedings of two conferences on terracottas in Genoa and Aix-en-Provence, and another on numismatics in Antalya, contain many papers of import and interest (Albertocchi, Cucuzza and Giannattasio Reference Albertocchi, Cucuzza and Giannattasio2018; Tekin Reference Tekin2021; Aurigny Reference Aurigny2022). Volumes that foreground archaeological context and have material of value to the study of Greek art include one in Copenhagen in 2017 looking at ancient Rhodes and another held in the same year commemorating 25 years of research at Argilos (Schierup Reference Schierup2019; Bonia and Perreault Reference Bonia and Perreault2021).

Edited tomes assembled by colleagues and students, and commemorating the life and work of major scholars of Greek art, remain a both standard and delightful feature of our field. Such volumes continue to be treasure troves of unpublished material and often incorporate creative forays unsuited to other venues. Some are quite hefty and their coverage broad in approach and material, while still reflecting well the careers of their honorand. In this category would be those for Heide Froning (Korkut and Özen-Kleine Reference Korkut and Özen-Kleine2018), Bert Smith (Draycott et al. Reference Draycott, Raja, Welch and Wootton2018), Eva Simantoni-Bournia (Lambrinoudakis, Mendoni and Koutsoumbou Reference Lambrinoudakis, Mendoni and Koutsoumbou2021), Georgia Kokkorou-Alevras (Kopanias and Doulfis Reference Kopanias and Doulfis2020), Stephanie Böhm (Danner and Leitmeir Reference Danner and Leitmeir2023), and one forthcoming for Jenifer Neils (Rogers, Smith and Steiner Reference Rogers, Smith and Steinerforthcoming). Others emphasize more exactly the individual scholar’s influence and contribution, such as the Early Iron Age in the case of Nota Kourou (Vlachou Reference Vlachou2017); pottery or vases for Stella Drougou, François Villard, and François Lissarrague (Giannopoulou and Kallini Reference Giannopoulou and Kallini2016; Gaultier, Rouillard and Rouveret Reference Gaultier, Rouillard and Rouveret2019; Zachari, Lehoux and Niddam Reference Zachari, Lehoux and Niddam2019); sculpture for Olga Palagia (Goette and Leventi Reference Goette and Leventi2019), and another in the planning stages in memory of Andrew Stewart; and portraiture for Dietrich Boschung (Lang and Marcks-Jacobs Reference Lang and Marcks-Jacobs2021). More archaeological in focus, though still beneficial, are volumes for Stephen Miller (Katsonopoulou and Partida Reference Katsonopoulou and Partida2016), Anthony Snodgrass (Nevett and Whitley Reference Nevett and Whitley2018, connected with a conference to celebrate his 80th birthday), and Vasileios Petrakos (Kalogeropoulos, Vassilikou and Tiverios Reference Kalogeropoulos, Vassilikou and Tiverios2021). A final group of Festschriften place Greek art in wider conversation with the expanse of the ancient Mediterranean world; namely, those for Linda-Marie Günther, Jan Bouzek, Michael Vickers, and the late Gocha Tsetskhladze (Beck et al. Reference Beck, Eckhardt, Michels and Richter2017; Pavúk, Klontza-Jaklová and Harding Reference Pavúk, Klontza-Jaklová and Harding2018; Sekunda Reference Sekunda2020; Boardman et al. Reference Boardman, Hargrave, Avram and Podossinov2022).

Pottery and vase-painting

The study of ancient figure-decorated pottery remains one of the healthiest and most prolific sub-disciplines of Greek art. This is in no small part represented by the ongoing spate of Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum (CVA) volumes that continue to make their appearance from museums and collections across Europe, the United States, and beyond. Founded in 1922, the 100-year anniversary of the CVA occasioned a sizable gathering of Greek vase specialists in Brussels, the published proceedings of which are already underway. The presentation and place of CVA volumes within the modern study of Classical art and archaeology deserve an essay in its own right. Be they centred on period or style, as in Geometric and Corinthian wares in Dresden (Dehl-von Kaenel Reference Dehl-von Kaenel2019), on shapes, such as olpe, oinochoai, skyphoi, and kyathoi in Berlin (Schöne-Denkinger Reference Schöne-Denkinger2021), on technique, such as the Attic black- and red-figure vases from Ruvo (Giudice and Giudice Reference Giudice and Giudice2022), a combination of features, as in Attic black-figure hydriae in Munich (Kreuzer Reference Kreuzer2017), or the corpus of a collection, such as the Gustavianum-Uppsala University Museum (Blomberg, Nordquist and Roos Reference Blomberg, Nordquist and Roos2020), the labour, expertise, and expense involved in producing such volumes cries out for digital publication and a fully searchable and collaborative online home moving forward (an updated version of CVA online started by the Beazley Archive some years ago: https://www.cvaonline.org/cva/Home). The Getty has been the first museum to publish a fully online Open Access CVA, that on Athenian red-figure kraters, and we shall see if this idea takes hold (Tsiafakis Reference Tsiafakis2019). Meanwhile the Beazley Archive (which celebrated its 50th anniversary with an international workshop in Oxford) and its pottery database (https://www.carc.ox.ac.uk/carc/pottery) endures as the point of entry for students and scholars exploring Athenian vases as part of their research, with newer enterprises, such as AtticPOT (https://atticpot.ipet.gr/index.php/en/) and Kerameikos.org (http://kerameikos.org/; Fig. 8.3 ), providing additional digital portals through which to introduce and explore this vast subject.

8.3. Kerameikos.org website, detail of homepage. © Kerameikos.org.

Painter and potter monographs are largely a thing of the past, as are, for the most part, isolated studies of a single vessel, and one must look elsewhere to find them (i.e. journals, edited volumes). Notable exceptions are Mario Iozzo’s guide to the François Vase (Reference Iozzo2018b), available in Italian and in English, and Nigel Spivey’s fascinating and highly readable The Sarpedon Krater: The Life and Afterlife of a Greek Vase (Reference Spivey2019). Collected papers on Greek vases that cover many different aspects – from production to consumption, connoisseurship to collecting – are appearing regularly in two important series: Studi miscellanei di ceramografia Grece produced at the University of Catania (e.g. Giudice and Giudice Reference Giudice and Giudice2020); and the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Österreich Beiheft, based on thematic symposiums organized by the Austrian Academy of Sciences (e.g. Kästner and Schmidt Reference Kästner and Schmidt2018; Lang-Auinger and Trinkl Reference Lang-Auinger and Trinkl2021). The pottery industry of Archaic Corinth is covered in Eleni Hasaki’s insightful publication of the Penteskouphia pinakes, including a chapter on ‘technology, workforce and organization’ (Reference Hasaki2021). Vase inscriptions, especially problematic ones, and their meanings remain topics of analysis, be they painted on Tyrrhenian amphorae (Chiarini Reference Chiarini2018) or incised before firing (Iozzo Reference Iozzo2018a). In a related vein is the study of painted goblets from Alexandria which dates them to the Hellenistic period and situates their production in the northwestern Nile Delta (Rodziewicz Reference Rodziewicz2020).

Vessel forms, regional production and the ceramics trade are each represented consistently in scholarship, though deriving from different sources and often representing various agendas. Attic black-figure skyphoi have generated a widely-useful and updated monograph (Malagardis Reference Malagardis2017), while cups of the same technique and region, those from the Campana Collection housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Florence, have now been carefully presented and illustrated (Heesen and Iozzo Reference Heesen and Iozzo2020). A second volume of vases in the Astarita Collection of the Museo Gregoriano Etrusco in the Vatican has appeared, this one covering, among other areas, Attic bilingual examples (Rocco Reference Rocco, Gaunt, Iozzo and Paul2016). Panathenaic prize amphoras are the topic of two noteworthy publications by Norbert Eschbach, who catalogues finds from the Kerameikos (Reference Eschbach2017) and by Martin Streicher who hones in on their Hellenistic phase (Reference Streicher2022). In addition to publications of regional fabrics already mentioned, South Italian vases and their relation to Greek and indigenous ceramics continue to captivate our interest (e.g. Denoyelle, Pouzadoux and Silvestrelli Reference Denoyelle, Pouzadoux and Silvestrelli2018; Kästner and Schmidt Reference Kästner and Schmidt2018; Chamay Reference Chamay2021). Relatedly, several other publications look at issues of mobility and trade in ancient figured-decorated pottery, questioning notions of production, commerce, distribution, and artistic transferal. Particularly thoughtful are: the contributions of Delphine Tonglet (Reference Tonglet2018) and Sheramy Bundrick (Reference Bundrick2019), each of whom enters the ongoing debate about Athenian vases in Etruria; an edited volume of essays from a conference panel in 2018 on shapes and markets for Greek and Etruscan vases (Paleothodoros Reference Paleothodoros2022); Nathan Arrington, who addresses anew Athens and her connections during the seventh century (Reference Arrington2021); a recent edited collection of papers that explores the context and uses of Attic pottery discovered in some of the more out-of-the-way locations (Fernández and García Reference Fernández and García2023); and another entitled Thrace Through the Ages, though not limited to antiquity in the region (Erdem and Şahin Reference Erdem and Şahin2023).

Finally, book-length publications on vase iconography and its contribution to Greek visual culture combine well-worn concerns with some more recent ones. The subjects are as varied as the images themselves and many, if not all, cover older territory in newer ways. Collectively, they suggest the traditional aspects of all that is Greek vases alongside a restlessness to move forward. Vases related to the Trojan War, its themes and heroes, continue to bear fruit in studies that combine texts and images, either jointly or separately: e.g. the Iliad, Menelaus, supplication (Pedrina Reference Pedrina2017; Stelow Reference Stelow2020, ch. 4; De Miro Reference De Miro2021b). Mythological figures and stories are much less in vogue than they once were, though a book on Adonis in South Italian vase-painting is one notable exception (Cambitoglou and Descoedres Reference Cambitoglou, Descoedres and McLoughlin2018). Eleni Manakidou bridges myth and cult in her assessment of females who dance for Dionysos on late Archaic Athenian vases (Reference Manakidou2017). Comparable are two books focused on vases as evidence for ritual practices that demonstrate entirely different approaches. One is a well-illustrated overview of the symposion as an Athenian institution by one of the field’s most respected scholars, produced in coordination with the Gerovassiliou Wine Museum (Tiverios Reference Tiverios2021); the other is an interdisciplinary study of wreathed figures in festival contexts that considers the symbolic interplay of human, object, and nature (Tempel Reference Tempel2020). Yet a different approach to the natural world is taken by Nikolina Kéi (Reference Kéi2021), who revisits flowers and floral ornamentation on vases, and the cultural values and sensorial aspects they potentially represent: a topic itself representative of De Gruyter’s outstanding Image and Context (ICON) series on antiquity. An innovative approach to the so-called Phlyax vases of South Italy and Sicily moves beyond the matching of text and image to assess the semantic structure of the scenes and, importantly, the context of their use (Günther Reference Günther2022). Two recent books deal with everyday individuals and their sphere of activity on vases: John Oakley’s introductory ‘guide’, suitable both for beginners and those in need of reference (Reference Oakley2020); and a thorough investigation of different types of labour on vases, including both artisanal (handwerklicher) and agricultural (landwirtschaftlicher) (Distler Reference Distler2022). Written from an (art) historical perspective is Robin Osborne’s The Transformation of Athens (Reference Osborne2018), a sustained discussion of an important moment of cultural, technical, and iconographic transition for Greek vase imagery and for Greek art in general, that attempts to distance the subject from the makers (potters and painters) and towards the socio-cultural context that produced and presumably used them.

Sculpture and terracottas

Sculpture, like vases, has featured throughout this review already, and interest in Greek art’s historically most revered subject shows no sign of waning. General introductions include a handbook by Olga Palagia (Reference Palagia2019), one of the field’s most influential and prolific scholars, and another written by Seán Hemingway (Reference Hemingway2021), curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Individual works – from the Getty Kouros to the Riace warriors, the Kairos of Lysippos to the Nike of Samothrace – lend themselves well to cultural history, object biography, contextual study, and even controversy (e.g. Settis and Paoletti Reference Settis and Paoletti2015; Azoulay Reference Azoulay2017; Clinton et al. Reference Clinton, Laugier, Stewart and Wescoat2020; Latini Reference Latini2022; Marx Reference Marx2022; Shortland and Degryse Reference Shortland and Degryse2022). Interventions on style, chronology, and artists continue to be produced, mostly taking the form of journal articles (e.g. Adornato Reference Adornato2019, Severe Style; Goette Reference Goette2021, Archaic; Kansteiner Reference Kansteiner2021, Polykleitos). Other publications seek out wider technical, stylistic, and historical connections that can be drawn from sculptures, among them edited volumes on Greek and Roman Bronzes (Descamps-Lequime and Mille Reference Descamps-Lequime and Mille2017), another on the ‘intermediality’ of sculpted image and inscribed text (Dietrich and Fouquet Reference Dietrich and Fouquet2022), and a series of lectures given in Paris that connects sculptures of all periods to images on vases, mosaics, and other arts (Hölscher Reference Hölscher2018). In addition to the site reports mentioned above, examples of both free-standing and architectural sculpture connected to specific sites (e.g. Barletta Reference Barletta2017, Sounion; Barringer Reference Barringer2021, Olympia; Higgs Reference Higgs2021, Bassai; Stewart Reference Stewart2023, Athenian Agora) or regions (e.g. Andrianou Reference Andrianou2017, Thrace; Machaira Reference Machaira2019, Rhodes) are very much in keeping with increased attention to archaeological context in critical studies of the Greek past, as well as a demonstrated need to incorporate legacy data.

Thematic studies of Greek sculpture are somewhat particular to the sub-field. As in other arenas, however, mortuary contexts and religious ritual are especially well-served. They include various books, catalogues, and articles, and intersecting themes such as gesture, emotion, and memory with reliefs, monuments, and cult statues (e.g. Andrianou Reference Andrianou2017; Hölscher Reference Hölscher2018; Margariti Reference Margariti2019; Michailidou Reference Michailidou2020; De Potter Reference De Potter2022). An illustrated account of funerary monuments in the Metropolitan Museum of Art situates large-scale sculpture alongside other visual and material expressions of death and afterlife (Zanker Reference Zanker and Shapiro2021; cf. Estrin Reference Estrin2023, on death and emotion). Portraiture in Greek sculpture continues to yield fruitful results with renewed studies of public and private individual representations (Biard Reference Biard2017; Ghisellini Reference Ghisellini2022), issues of realism and verism (Dillon, Prusac-Lindhagen and Lundgren Reference Dillon, Prusac-Lindhagen and Lundgren2021), and period-specific studies of the Classical and the Hellenistic (Queyrel Reference Queyrel2020; Fiorello di Bella Reference Fiorello di Bella2021). A third discernible area of interest is in the reuse and reception of Greek sculpture, as demonstrated by Rachel Kousser’s The Afterlives of Greek Sculptures (Reference Kousser2017), an iconoclastic approach to the problem, and Sarah Rous’ Reset in Stone, which repackages spoliation as ‘upcycling’ (Reference Rous2019). Two publications take a welcome new look at plaster casts, their collections, past importance, and present potential in the digital realm: one stemming from two conferences (Alexandridis and Winkler-Horaček Reference Alexandridis and Winkler-Horaček2022) and the other solely occupied with the Parthenon sculptures (Payne Reference Payne2021). Related is the Digital Sculpture Project (http://www.digitalsculpture.org/; Fig. 8.4 ), which uses 3D technology to document, analyse, and reproduce famous works from ancient Greece and beyond, most recently the Laocoön Group.

8.4. Digital Sculpture Project, detail of homepage. © Bernard Frischer.

On the smaller scale are terracotta sculptures that continue to be discovered in abundance on archaeological sites, as noted above, and also to be examined in their own right. Key contributions to coroplastic studies include exhibitions, such as one in Berlin focused on the context of their use (Veldhues and Schwarzmaier Reference Veldhues and Schwarzmaier2022); museum collections (e.g. Panait-Bîrzescu, Sîrbu and Głuszek Reference Panait-Bîrzescu, Sîrbu and Głuszek2019); themes, such as agency (Hoffmann Reference Hoffmann2023) or heroic figures of myth (Möller-Titel Reference Möller-Titel2019); regional production and use, as at Akragas (Van Rooijen Reference Van Rooijen2021); and/or types, such as masks from Magna Graecia (Todisco Reference Todisco2020). Two other publications consider relevant material that bridges that somewhat tricky Hellenistic–Roman divide (Papantoniou, Michaelides, Dikomitou-Eliadou Reference Papantoniou, Michaelides and Dikomitou-Eliadou2019; Galbois and Autin Reference Galbois and Autin2023). New potential for the reception of monumental Greek sculpture coupled with the modesty of terracotta figurines is unlocked in the discussion of a model of the Athena Parthenos in Liverpool, redated from the Roman period to the 19th century (Muskett Reference Muskett2019).

Painting, colour, mosaic

Ancient Greek painting appears to be back in vogue, as evidenced by the edited volume of J.J. Pollitt that covers Minoan to Roman (Reference Pollitt2015), and more recently by Dimitris Plantzos’ much-needed general introduction, The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece (Reference Plantzos2018, in English and Greek; Fig. 8.5), that incorporates the archaeological, textual, stylistic, and technical aspects of both wall- and panel-painting over time. An edited volume grappling with ancient painting and the digital humanities addresses vital research questions and methods and integrates the Digital Milliet Project (https://digmill.perseids.org/), a database assembling ancient Greek and Latin texts on painting from the sourcebook of the French academic painter, Paul Milliet (Beaulieu and Toillon Reference Beaulieu and Toillon2021). The 50-year anniversary of the discovery of the Tomb of the Diver paved the way for an exhibition and various publications that revisit its meaning, reconsider its artistry, and reinforce its significance in the history of ancient painting. Compared by some to Etruscan painting and by others to Greek vases (cf. Zuchtriegel Reference Zuchtriegel2018; Meriani and Zuchtriegel Reference Meriani and Zuchtriegel2020; Hölscher Reference Hölscher2021), a recent archaeometric study concludes that the tomb represents its own local artistic tradition (Alberghina et al. Reference Alberghina, Germinario, Bartolozzi, Bracci, Grifa and Izzo2020). Closely related to the history of ancient painting is the issue of colour, an area of inquiry that continues to advance as a result of non-invasive techniques of analysis with promising results also applied to sculpture (cf. Brinkmann, Dreyfus and Koch-Brinkmann Reference Brinkmann, Dreyfus and Koch-Brinkmann2017; Verri et al. Reference Verri2023). It is the theme of a massive edited volume (originating as a conference) crediting a wide range of perspectives, materials, and approaches (Jockey Reference Jockey2018), as well as a book by Jennifer Stager, who explores the subject via various artistic media, materiality, textual traditions, and the modern white-washing of the Classical past (Reference Stager2022). Mosaics have also been the subject of two studies with rather different aims. The first is a contextual reading of mosaics within the space of the symposion, providing an intelligent complement to previous studies by mixing in the role of wine and material objects in a participant’s experience (Franks Reference Franks2018). The second, abundantly illustrated and published in Greek, traces the history and development of figural mosaics in Greece from the fifth century BC to the seventh century AD (Asimakopoulou-Azaka Reference Asimakopoulou-Azaka2023).

8.5. Cover of The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece. © Dimitris Plantzos.

Metals, coins, gems, and jewellery

There are a few significant recent studies dedicated exclusively to metals. These include the site report from Delphi covering bronze tripods, cauldrons, and vessels already mentioned (Aurigny Reference Aurigny2019); the latest book by Nassos Papalexandrou (Reference Papalexandrou2021) on bronze griffin cauldrons scrutinized through technical aspects, formal qualities, and viewer experience; and the stunning second volume of a catalogue of metal vessels and utensils (e.g. Thracian, Anatolian, Greek) in the Vassil Bojkov collection in Sofia, dedicated to the memories of Jan Bouzek and Claude Rolley (Sideris Reference Sideris2021). Another aims to revitalize the discussion of Greek arms and armour by assembling data from excavations and, specifically, appreciating how such objects operated in the funerary context of Hellenistic Macedonia (Juhel Reference Juhel2017). A lengthy article has appeared on gilded wreathes from Late Classical and Hellenistic Greece, including typology and technique, where again mortuary practices are centred, while other contexts also explored (Jeffreys Reference Jeffreys2022). On a more modest scale are the lead votive figurines from Spartan sanctuaries, representing gods, mortals, animals, and objects, which continue to capture our attention and present challenges of style, chronology, and scientific analysis (e.g. Lloyd Reference Lloyd, Tarditi and Sassu2021; Braun and Engstrom Reference Braun and Engstrom2022).

Coins and their images are envisioned increasingly as belonging to the history of ancient art. This aspect has been featured in a variety of publications, among them François de Callataÿ’s L’incomparable beauté des monnaies grecques. Les raisons qui fondent leur admiration, published by the Benaki Museum in Reference De Callataÿ2016, and again in Greek in 2020. Others are the exhibition at the Museum of Cycladic Art and its accompanying catalogue Money: Tangible Symbols in Ancient Greece, published in Greek and English and comprising a section on ‘money and art’ (Stampolidis, Tsangari and Tassoulas Reference Stampolidis, Tsangari and Tassoulas2017), the edited conference volume ΤΥΠΟΙ: Greek and Roman Coins Seen through Their Images (Iossif, de Callataÿ, Veymiers Reference Iossif, de Callataÿ and Veymiers2018), and most recently an exhibition and catalogue celebrating 50 years of the Alpha Bank Numismatic Collection in Greece entitled The Other Side of the Coin: Persons, Images, Moments (Tsangari Reference Tsangari2023, also in Greek). Other iconographic and historical studies consider portraiture, decorative motifs, symbols, and animals, and associations between coins, other arts, and archaeology (e.g. Campagnolo and Fallani Reference Campagnolo and Fallani2018; Castrizio Reference Castrizio2018; Kakavas and Papaevangelou-Genakos Reference Kakavas and Papaevangelou-Genakos2019; Fischer-Bossert Reference Fischer-Bossert2020; Pangerl Reference Pangerl2020; Sidrys Reference Sidrys2020). Several volumes have a specifically locational emphasis: e.g. Peloponnese, Arcadia, Crete, Cyrenaica, western Greece, Marseille, Phokaia, and Cimmerian Bosporus (Depeyrot Reference Depeyrot2017; Apostolou and Doyen Reference Apostolou and Doyen2018; Asolati and Crisafulli Reference Asolati and Crisafulli2018; Stampolidis, Tsangari and Giannopoulou Reference Stampolidis, Tsangari and Giannopoulou2019; Abramzon and Kuznetsov Reference Abramzon and Kuznetsov2021; Traeger Reference Traeger2021; Wahl Reference Wahl2021; Devoto Reference Devoto2022; Pekin Reference Pekin2022). Publications of museum holdings and private collections – and in one case an account written by a collector (Eaglen Reference Eaglen2017) – include Greek material, addressing the matter of coins as art and adding to the existing corpus of illustrated examples (e.g. Dotkova, Russeva and Bozhkova Reference Dotkova, Russeva and Bozhkova2018; Burrer et al. Reference Burrer and Simon2020; Arslan, Peter and Stolba Reference Arslan, Peter and Stolba2021; Çizmeli-Öğün and Toumpan Reference Çizmeli-Öğün and Toumpan2022).

Gems and jewellery, normally listed as ‘minor’ or ‘luxury’ arts, are found in many of the exhibition catalogues listed above, but have also been given attention in their own right. Over the past decade or so, John Boardman and Claudia Wagner have published several private gem collections that serve to tell the story of this superb and surprisingly underappreciated art form from antiquity to the modern day. Singled out for mention is Masterpieces in Miniature: Engraved Gems from Prehistory to the Present (Reference Boardman and Wagner2018), a beautifully produced book of more than 250 examples, all reproduced with high-quality colour figures and an index of impressions. In keeping with the turn towards animal studies, it is predictable, given the impressive range of creatures on engraved gems, that these have now been granted their own account, albeit one derived exclusively from the collection of the Israel Museum, Jerusalem (Sagiv Reference Sagiv2018). Gems are included in combination with other source materials in Christopher Faraone’s Reference Faraone2018 study of Greek and Roman amulets, seen as objects of cultic and magical significance – a topic taken up again in the published proceedings of a workshop held in Budapest (Endreffy, Nagy and Spier Reference Endreffy, Nagy and Spier2019). The iconography, portraiture, and ideology of Hellenistic seal impressions, another tiny art form, are presented in a conference volume incorporating evidence from across the Mediterranean sphere (Van Oppen de Ruiter and Wallenfels Reference Van Oppen de Ruiter and Wallenfels2021). Interestingly, some recent publications on jewellery reveal related thematic and chronological trends. The Hellenistic gold jewellery in the Benaki Museum has been the subject of detailed study that enhances our understanding of both craft and trade (Jackson Reference Jackson2017). The acts of a colloquium published in Gemmae, an annual devoted to ancient glyptic studies launched in 2019, looks at jewellery (both by type and as a conceptual category) across antiquity (including Greece) for its social, cultural, anthropological, and religious implications (Dasen and Spadini Reference Dasen and Spadini2020). Coins and jewellery are expertly combined in the conference proceedings of an event held on the island of Ios back in 2009, as portable antiquities with shared qualities, messages, and sometimes even motifs (Liampi, Papaevangelou-Genakos and Plantzos Reference Liampi, Papaevangelou-Genakos and Plantzos2017).

Iconography and theme, object and material

It should go without saying that among the most useful and thought-provoking contributions are those which address Greek art by looking at its images and objects collectively, thematically, and materially. Many publications fixed more narrowly around a certain category, such as vases or coins, have already been mentioned. While space does not permit the in-depth treatment that these authors and their works deserve, collectively they demonstrate especially well the ongoing and new concerns of the field and its potential to speak to a broader audience. Several are general treatments of Greek art exclusively or as understood in relation to other ancient Mediterranean traditions (e.g. D’Agostino and Cerchiai Reference D’Agostino and Cerchiai2021). Divided by genre and suitable for less-familiar or student readers is Eva Rystedt’s Excursions into Greek and Roman Imagery (Reference Rystedt2023). Based on his Sather lectures is Tonio Hölscher’s Visual Power in Ancient Greece and Rome: Between Art and Social Reality (Reference Hölscher2019c), which views images through the lens of lived experience and human interactions, including political and religious ones, and packaged through themes such as space and time. Taking a more philosophical approach, and overlapping with increased attention to the sensory, are two monographs on aesthetics and Greek art – each with a mixture of textual and art historical charm (Witcombe Reference Witcombe2018; Grethlein Reference Grethlein2020). Also to list for their pioneering approaches to and applications of Greek art are an inspiring edited volume on the materiality of ancient art in Pliny (Anguissola and Grüner Reference Anguissola and Grüner2020); a monograph on attributes and their entanglements (Dietrich Reference Dietrich2018); chapters in an edited volume analysing the concept of ‘l’aspective’ (Barbotin et al. Reference Barbotin2017); and a thoughtful introduction to the phenomenology of time (Kim Reference Kim, Doering and Ben-Dov2017).

Myth, epic, and stubborn beholdenness to ancient texts in Classical archaeology writ large are being treated with less enthusiasm than they once were, allowing Greek visual images and material objects a chance to find their feet theoretically and methodologically. Thus, several recent publications in this area attack these topics anew and in an arguably more truly interdisciplinary manner than ever. Two of relevance are by the same author, Tonio Hölscher, and offer models of the ways seemingly exhausted topics can still deliver. In one, the author explores the theme of war in Greek and Roman art (Reference Hölscher2019a), while in the other the emphasis is on myth in Athenian art at a specific historical moment, the turn of the fifth century (Reference Hölscher2019b). The acts of a colloquium at Centre Jean Bérard in Naples demonstrate how giants and the gigantomachy are widespread phenomena across ancient regions and periods (Massa-Pairault and Pouzadoux Reference Massa-Pairault and Pouzadoux2017, open edition 2020). Also absorbed in specific figures and their narratives, and combining literary, cultic, and artistic analyses, are: an edited volume on Hermes, originating as a conference at the University of Virginia (Miller and Clay Reference Miller and Clay2019); a cultural history of the Cyclops incorporating images, stories, and reception (Aguirre and Buxton Reference Aguirre and Buxton2020); the events and publications of The Hercules Project, based at the University of Leeds (e.g. Blanshard and Stafford Reference Blanshard and Stafford2020; cf. https://herculesproject.leeds.ac.uk/; Frade Reference Frade2023); and an edited volume on Nikai in ancient Greek art to accompany an exhibition in Athens already listed (Lagogianni-Georgakarakos Reference Lagogianni-Georgakarakos and Doumas2021). Less scholarly but no less interesting is Kathleen Vail’s Reconstructing the Shield of Achilles (Reference Vail2018), written from a modern artist’s perspective (cf. https://theshieldofachilles.net/).

The two themes that have generated the most interest recently are religion and performance. The former has seen a barrage of publications across the Classical world of late, the latter is a long-standing concern that continues to evolve in academic discourse. The late Erika Simon’s The Gods of the Greeks (Reference Simon, Zeyl and Shapiro2021) is an English translation of her German masterpiece written from an archaeological perspective and delving into human perceptions and worship of the gods. Building on her work and written from a broad perspective, though privileging examples on the smaller scale (i.e. vases, plaques, figurines), is Tyler Jo Smith’s Religion in the Art of Archaic and Classical Greece (Reference Smith2021). Other significant publications incorporating religion and art have appeared on libation (Gaifman Reference Gaifman2018), mystery cults (Belayche and Massa Reference Belayche and Massa2020), materiality (Rask Reference Rask2023), and sensory experience (Grand-Clément Reference Grand-Clément2023). Performance in visual translation, including musical, choral, and dramatic, have all been the subject of renewed study that transcends the age-old matching of image and text and the recreation of lost ephemeral arts to explore such issues as presence and the body (e.g. Jackson Reference Jackson2019; Gétreua and Vendries Reference Gétreua and Vendries2021; Steiner Reference Steiner2021; Piqueux Reference Piqueux2022). The comprehensive new edited volume on satyr drama includes several chapters on art in a section devoted to archaeological evidence (Antonopoulos, Christopoulos and Harrison Reference Antonopoulos, Christopoulos and Harrison2021), while many publications connected with the Locus Ludi project based at the University of Fribourg also contain aspects essential to the study of Greek art and culture (e.g. Dasen Reference Dasen2019, an exhibition catalogue; cf. https://locusludi.ch/).

A second pairing of interests has centred on the body and adornment. Neither are new subjects, and their persistence is striking though evolving. There is a general shying away from the ideal with subjects such as the grotesque, old age, disability, dismemberment, and disease each making an appearance (Laios Reference Laios2015; Gherchanoc and Wyler Reference Gherchanoc and Wyler2020; Adams Reference Adams2021; Matheson and Pollitt Reference Matheson and Pollitt2022; Meintani Reference Meintani2022; Vout Reference Vout2022). Bodily adornment, as understood though dress, footwear, and textiles, has resulted in edited volumes placing the Greek artistic evidence alongside that from neighbouring regions (Pickup and Waite Reference Pickup and Waite2018; Batten and Olson Reference Batten and Olson2021; Harris, Brøns and Zuchowska Reference Harris, Brøns and Zuchowska2022). Embedded in these studies are adjacent issues such as gender and social status. These works, along with others directly addressing transformation, sexuality, ‘blackness’, and other timely topics, are laying the groundwork for intersectional approaches to Greek art going forward (Gondek and Sulosky Weaver Reference Gondek and Sulosky Weaver2019; Surtees and Dyer Reference Surtees and Dyer2020; Derbew Reference Derbew2022; Murray Reference Murray2022; Deacy, Magalhães and Menzies Reference Deacy, Magalhães and Menzies2023).

History, collecting, reception

The current state of Greek art, and its place both within and without adjacent fields, is in no small way exemplified by ongoing scholarly interest in its disciplinary and collecting history, as well as its reception. Publications swept up into these broad groupings have between them a good deal of overlap, yet are only rarely in conversation with one another because their authors are rather disparate. In short, this is an area of growth and importance that would benefit from greater unity and sense of purpose. Two hundred and fifty years of scholarship on Greek vases was commemorated at Oxford by an exhibition at Christ Church Library on Sir John Beazley and a companion publication (Mannack, Rodríguez Pérez and Neagu Reference Mannack, Rodríguez Pérez and Neagu2016). Beazley and his methods of analysis have again been revisited using new materials and perspectives that demonstrate at once his scholarly impact and his endless intellectual appeal (Rodríguez Pérez Reference Rodríguez Pérez2018; Driscoll Reference Driscoll2019). Beazley and many other figures of distinction are to be found in a fantastic edited volume, Drawing the Greek Vase (Meyer and Petsalis-Diomidis Reference Meyer and Petsalis-Diomidis2023), a series of case studies that question how two-dimensional reproductions of vases (i.e. drawings, prints, photographs) and their circumstances, from the 17th century to the 20th, have played a key role in modern perceptions of them as both art and artefact. Several publications have looked at the history of Greek art (including vases, coins, and architecture) through collecting practices and discoveries, naturally tied to early travel, excavations, and historical circumstances (e.g. Silvestrelli Reference Silvestrelli and Pietri2017; Adornato, Cirucci and Cupperi Reference Adornato, Cirucci and Cupperi2020; Weisser Reference Weisser2020; Boschung et al. Reference Boschung, Mathieux, Colonna and Queyrel2022). Not to be missed is the edited volume on Winckelmann coinciding with an exhibition at Oxford to commemorate – 300 years on – his lasting mark (for better or worse) on the study of Greek art (Neagu, Harloe and Smith Reference Neagu, Harloe and Smith2018).

While the reception of Greek art, from antiquity to modernity, maintains a steady stream of publications, it has by no means kept apace of broader trends in Classics and architectural history. The emphasis here is still very much the Western canon (i.e. European painting, Classical tradition, Neoclassicism), with the global potential of this area lingering largely untapped. Nevertheless, a book such as Caroline Vout’s Classical Art: A Life History from Antiquity to the Present (Reference Vout2018) presents a commendable overview of interest to Classical archaeologists and to art historians of many periods. Other studies are written from a striking array of expert perspectives, starting with a series of papers presented at the Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference in 2015 on Greek art in Roman contexts (Adornato et al. Reference Adornato, Romano, Cirucci and Poggio2018) and followed by the activities and outputs of the Gandhāra Connections project at Oxford’s Classical Art Research Centre (e.g. Rienjang and Stewart Reference Rienjang and Stewart2020). Moving beyond antiquity is an edited volume on ancient art, science, and nature in the Renaissance as understood through select ancient texts (Hedreen Reference Hedreen2021); the reception of ancient sculpture on the early modern viewer and its impact on art, packaged as ‘artistic and aesthetic encounters’ (Betzer Reference Betzer2022); a volume coinciding with the British Museum’s exhibition Rodin and the Art of Ancient Greece that includes Greek sculpture alongside the artist’s own drawings and sculpture (Farge, Garnier and Jenkins Reference Farge, Garnier and Jenkins2019); and an edited volume based on ancient artists in the textual tradition, perhaps of less direct use to classicists than those who study later periods (Hénin and Naas Reference Hénin and Naas2018). Two books by the same author tackle fin-de-siècle art movements, Art Nouveau and Symbolism, and their engagement with the Classical tradition and the Greek body, respectively, organized according to themes and mythological figures (Warren Reference Warren2019; Reference Warren2020). Thematic volumes include one responding to Classical monsters in popular culture and a single-authored ‘companion’ to episodes of ‘heroic’ rape and abduction in antiquity centred on four myths (Gloyn Reference Gloyn2020; Lauriola Reference Lauriola2022). The edited volume Classical Antiquity in Video Games (Rollinger Reference Rollinger2020) and the more recent Ancient Greece and Rome in Videogames (Clare Reference Clare2023) are bound to attract a large readership of enthusiasts and are included here for their appeal to the visual, along with Representations of Antiquity in Film: From Griffith to Grindhouse, though not limited to the Greco-Roman world (McGeough Reference McGeough2022).

Finally, two entirely different authors and their unique contributions to themes of history, collection, and reception combined need be highlighted. The first is the late William St Clair whose two new books on the Parthenon (originally conceived as one) cover between them the many lifetimes of the monument from its construction to the present day, especially within the context of modern Greece itself (from the revolution up to the present), the military conflicts it has witnessed, and the controversy surrounding ownership of removed elements (St Clair Reference St Clair, St Clair and Barnes2022a; Reference St Clair, St Clair and Barnes2022b). The second author is Dimitris Plantzos, who in recent years has produced an ongoing series of articles connecting modern Greece, along with its unique ups and downs (i.e. Olympic Games, financial crisis, street art, etc.), to its ancient past. Given the author’s expertise, most incorporate ancient Greek art in some manner, such as an essay on the Caryatid as a symbol of ‘Greekness’ both in Greece and elsewhere (Plantzos Reference Plantzos2017). Sure to make a lasting impact is his recent book written in Greek on ‘archaeopolitics’, which confronts the ways national narratives are built around and derive from materialities of the past (Plantzos Reference Plantzos2023).

Greek Art: what’s next?

The recent trends and current developments summarized here suggest a field that is both surviving and thriving. With no shortage of stake-holders – namely, authors and audiences with diverse academic interests – Greek art maintains its status as foundational and highly relevant. The bibliography being generated, both standard and digital, speaks to classicists, archaeologists, and historians, and offers abundant resources that no longer belong exclusively to trained specialists. Furthermore, the tired divide between empirical and theoretical approaches to the material feels more or less defunct, especially given increased attention to interdisciplinary and comparative scholarship on the one hand, and to the specifics of archaeological context on the other. Although there are traditional aspects and questions that persist, such as realism, beauty, and connoisseurship, there are by the same token opportunities taken to engage periods or themes anew or in novel ways (e.g. Hellenistic, religion, performance, senses, emotion, nature, death, the body) – and a new generation of writings more intersectional in outlook can be predicted. Importantly, it is the evolving position of ancient Greek art in the modern world, from Picasso to Freud, Peter Pan to ‘archaeopolitics’, that is slowly building a more inclusive Greek art, though one whose ability to enter the global conversation has yet to be realized. The inclusion of Greek art in wide-ranging volumes on ceramics and gesture (Greenhalgh Reference Greenhalgh2021; Gardner and Walsh Reference Gardner and Walsh2022), or in volumes produced by the Chicago Center for Global Ancient Art (e.g. Elsner Reference Elsner2020, on figurines), merely scratch the surface of what is possible moving forward.

Acknowledgements

My greatest thanks are owed to the editors of this issue for inviting my contribution and for their unwavering patience and assistance. I am grateful to the libraries of the BSA and the ASCSA and the Fine Arts Library at the University of Virginia where, collectively, the research for this review was done. For bibliographical assistance I wish to thank Mario Iozzo, Nicholas Harokopos, Adrienne Delahye, and Dylan Rogers; and for editorial help, Anna De Vincenz, Francesca Fiorani, and most of all Abigail Bradford. Finally, for permission to reproduce images, I am grateful to Bernard Frischer, Dimitris Plantzos, and Diana Rodríguez Pérez.