Introduction

[…] the number of students taking Latin GCSE has reduced by almost half, almost nobody learns Greek…Classical Studies…is very much a minority interest (Taggart, Reference Taggart2013, p. 13).

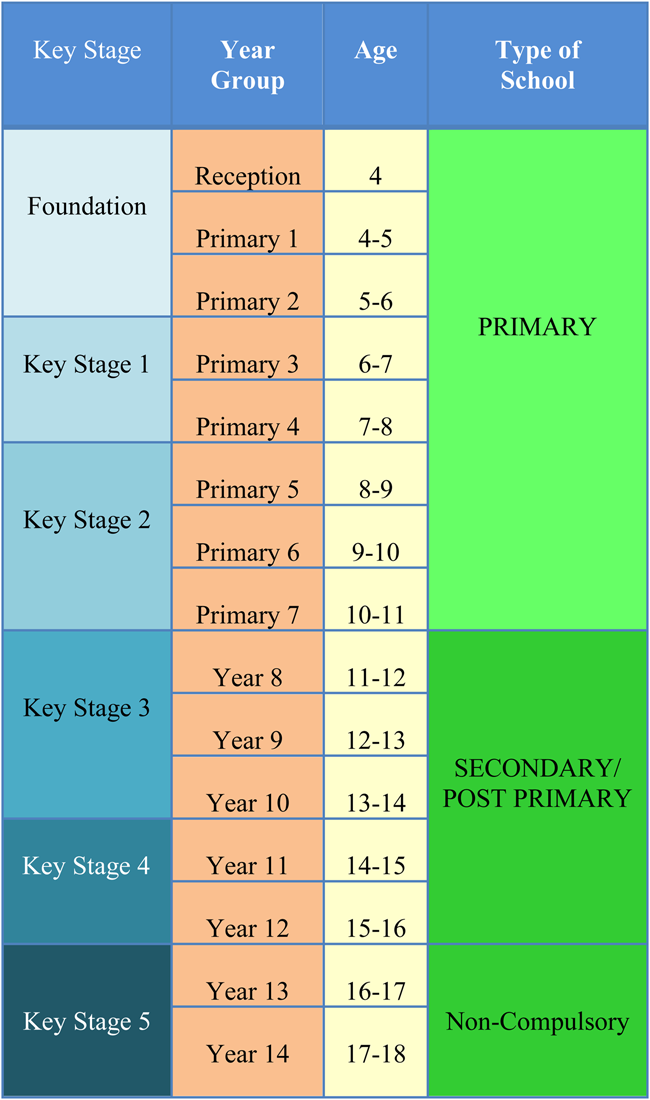

Classics is not compulsory in the Northern Ireland Primary Curriculum (CCEA, 2007). However, it is taught in a minority of Northern Irish post-primary schools, predominantly in the grammar sector. The Language Trends Northern Ireland Report in 2019 (British Council, 2019) showed that below ten per cent of post-primary (see Figure 1 for overview of Northern Ireland schooling) schools had Latin timetabled; less than five percent had it as an extra-curricular option. The most recent Language Trends Northern Ireland Report (British Council, 2021) showed that 0 per cent of surveyed schools had Latin as an option to pupils in Year Eight. Only one per cent had the option in Year Nine. This article considers the benefits and challenges of implementing Classics as part of the Northern Irish Curriculum (NIC) at the primary phase, for children aged nine to eleven.

Figure 1. The Education System in Northern Ireland.

The Northern Irish Curriculum

The NIC was revised in 2007 to be a framework rather than a content-based curriculum such as the English National Curriculum (Department for Education [DfE], 2013). According to the official NIC document (CCEA, 2007, p. 10), ‘children learn best when learning is connected’. The NIC framework is skills-infused (CCEA, 2007) allowing cross-curricular thematic units of learning (Greenwood, Reference Greenwood2013). Areas of learning that enable children to develop Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities such as ‘Working with Others’ and ‘Managing Information’ encourage the development of three key cross-curricular skills: ‘Communication’, ‘Using Mathematics’ and ‘Using ICT’ ( Jones, Reference Jones2020).

There are therefore no compulsory topics in the NIC (such as the Romans or the Ancient Greeks). Languages, including classical languages, are not required subjects at Primary level. Jones (Reference Jones2020) calls for CCEA (2007) to be revised so that all pupils in all schools are able to learn a new language. While observing Latin lessons in a socio-economically deprived primary school, she noted the positive impact on literacy attainment so recommended that languages, including Latin, be made compulsory in the NIC (Jones, Reference Jones2020).

Research from England suggests that Latin could be a positive addition to the NIC. Bell and Wing-Davey (Reference Bell, Wing-Davey, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) found that a headmaster chose to teach Latin because it better developed literacy attainment for newcomer children than other foreign languages. With 11,964 newcomer pupils in Northern Irish primary schools in 2020 (Department of Education [DENI], 2020, 2022), including Latin on the curriculum could be conducive to the policy aims of Every School a Good School (DENI, 2009).Footnote 2 In fact, by developing spoken classical linguistic skills, pupils, including newcomer pupils, are given the opportunity to enhance their social skills and promote independent thinking (Pike, in Hunt, Reference Hunt, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018). This is important when looking at the value of Classics in NI, especially considering the need to develop the whole child as envisaged by CCEA (2007).

Pring (Reference Pring2016) explains that Classics is a gateway to allowing students to become ‘more human’. Through Classics, pupils explore subjects such as philosophy, poetry, prose and history all under a common theme or ancient language (Khan-Evans, Reference Khan-Evans, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018). Within the Northern Irish context, Holmes-Henderson and Tempest's (Reference Holmes-Henderson, Tempest, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) research into twenty-first century skills supports the teaching of Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities (TSPCs) (CCEA, 2019) which ‘can help cultivate collaboration, initiative, productivity and leadership’ (Holmes-Henderson and Tempest, Reference Holmes-Henderson, Tempest, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018, p. 232). There is certainly a policy-linked opportunity here for Classics.

Methodology

This study explored the perspectives of teachers and pupils in NI in relation to the benefits, challenges and potential future for Classics in the NIC by analysing the following three research questions (RQs):

RQ1. What benefits, if any, does Classics bring to Northern Irish primary teachers and pupils?

RQ2. What challenges do teachers and pupils face in Northern Ireland in trying to implement Classics in their classroom?

RQ3. What future development is possible for Classics in Northern Ireland?

An interpretivist paradigm was chosen as it looks for opinion through discussion and the ‘human experience’ (Thanh and Thanh, Reference Thanh and Thanh2015). Data was gathered using purposive sampling to ensure that interview and focus group participants had enough experience of learning Classics to help explore the research questions (Foley, Reference Foley2018). The data collected using these methods was analysed using the constant comparison method, and a system of colour-coding was utilised to better assess emerging themes and ideas across the focus group and interviews (Thomas, Reference Thomas2017).

The two research methods used for this study were:

Focus group: qualitative data gathered from children who had some experience of Classics at school.

Semi-structured interviews: qualitative data gathered from six teachers from three different schools in NI. Two teachers had not taught any classical subject prior to the interview being conducted. Four teachers had either taught a classical topic themselves in the classroom or found ways in which to incorporate the subject into class time.

The six semi-structured interviews were conducted in the greater Belfast area with teachers from three separate schools (referred to as Schools A, B and C). In School A, Classics was neither facilitated by external visitors nor taught by the teachers themselves. School B hosted two teachers who had incorporated Classics in their classroom either through topic work, or through additional classes from a visitor prior to the study being conducted. School C taught a classical topic to Key Stage 2 pupils annually, over the course of a few weeks. The three schools were selected to bring together staff with a range of perspectives and experiences. Within each school, teachers were numbered 1 and 2 to maintain anonymity.

In School B, a focus group was conducted with eight children, who had experience of learning Classics on timetable. This was necessary to assess their views on the research questions. The focus group was conducted to hear the ‘pupil voice’ regarding learning about Classics in the primary classroom, securing a safe space for participation (Lundy, Reference Lundy2007). The children were questioned using child-friendly language to enable all to participate fully in the discussion (Kelly, Reference Kelly2013). Alongside questions, cue cards were used to increase participation by improving children's enjoyment and engagement in the research, as well as providing visual aids for the questions that followed (Gibson, in Kelly, Reference Kelly2013).

Results

Semi-structured Interview Results

Questions to establish provision of Classics

1. Do you currently offer any classical subject or topic to your pupils?

In School A, Teachers 1 and 2 answered that it was not offered as a full topic nor was it facilitated by external visitors; however, both mentioned that there may be an isolated lesson that happens to align with Classics in Key Stage 2.

In School B, Teacher 1 answered no, but stated that a visitor taught Latin for several weeks to Primary Seven. Teacher 2 currently teaches Classics as part of a Primary Six ‘Volcanoes’ topic with a focus on Pompeii but does not teach a classical language.

Both teachers in School C stated that Classics was offered through their Primary Six topic ‘The Romans’. This was cross-curricular, incorporating Numeracy and Literacy. Teacher 1 suggested that Primary Six students had some experience of Latin. Teacher 2 explained that Classics may also be offered through a Key Stage 1 topic in the school, such as ‘The Ancient Greeks’ but was uncertain.

2. (Directed question: School A) What Key Stage/class would you implement a classical subject into?

Teachers 1 and 2 considered Key Stage 2 most appropriate. Teacher 2 believed Primary Six/Seven to be optimal due to developing skills in making comparisons. Teacher 1 preferred Ancient History considering its direct links to the curricular area known as ‘World Around Us’ (WAU). Teacher 2 favoured Classical Civilisation topics as an option, considering pupil interest in culture and mythology.

RQ1: Benefits of Classics for teachers and pupils

1. Do you see any benefits in learning a Classical language to boost Literacy attainment?

All participants agreed that showing links between words in Latin or Ancient Greek with English aids spelling and vocabulary understanding. Teachers 2 in Schools B and C said it helps develop understanding of grammatical functions such as using prefixes/suffixes that are rooted in Latin. Teachers 1 in Schools B and C noted that linking Latin words to their English derivatives was beneficial to stretching higher-ability pupils.

2. Do you consider Classics to have benefits for cultural awareness?

All teachers said that the study of Classics would benefit children's understanding of cultural heritage. Both teachers in School B believed that it would help pupils appreciate popular movies by understanding classical references.

The teachers in School C said it developed understanding of change over time, due to the migration patterns of the Romans as well as developing an appreciation for today's multicultural society in comparison to Ancient Rome's.

3. Do you think that studying a classical language may aid in supporting MFL understanding?

All teachers said that learning a classical language supported successful progress in MFL because of similarities between languages in grammar and vocabulary. In School C, Teacher 1 highlighted that it would have to be a European language with roots in Latin.

School B Teacher 2 stressed that a distinction would have to be made between classical and MFL vocabulary words so that children did not become confused.

Five teachers saw classical languages as beneficial for newcomer children, but priority lay with teaching English. School A Teacher 2 was unsure, believing there to ‘be enough’ for newcomer children to learn already.

Four teachers (Schools A and C Teacher 1 and Schools B and C Teacher 2) considered the languages a good tool for inclusion.

RQ2: Challenges of integrating Classics into the Classroom

1. Do you think the study of Classics is hard to support if some see it as ‘irrelevant’?

Three teachers (School A Teacher 1; School B Teachers 1 and 2) said it would be hard to make an argument for Classics in school unless it were considered relevant by senior management.

Three teachers (School A and C Teacher 2; School C Teacher 1) believed it would be difficult to promote in a school unless it could be presented meaningfully. They suggest that if the children showed enthusiasm for the subject, then the problem is diminished.

In School A, both teachers believed people found other subjects more important for life skills; Teacher 2 in School C agreed. Both teachers in School B believed lack of experience in studying the subject contributed to perceptions of its irrelevance. Within School C, Teacher 1 (who is from England), felt the Romans and their culture were not as applicable to a Northern Irish context compared to England.

2. Do you find there is a stigma of elitism surrounding the subject, hindering its development?

All teachers felt there was a stigma of elitism apart from School A Teacher 1 who stated that if there were a stigma of elitism, they have ‘never actually been aware of one.’ All other teachers suggested that this stigma was caused by the subject only being offered in select grammar schools in NI, limiting the number who could study it.

3. (Directed question: School A) Why are classical subjects not currently offered at your school?

Teacher 1 stated that there was no one in the school with a passion to lead any classical subject. Teacher 2 held similar views, adding that it was probably because it was not statutory on the NIC.

RQ3: Future Development of Classics in Northern Ireland primary schools

1. If you could design your dream curriculum, would Classics have its own place?

Teacher 1 in Schools B and C, as well as School A Teacher 2, would include Classics on their curriculum, although Teacher 1 in School C cautioned that teachers may see it as an imposition unless utilised strategically.

The other three teachers answered no. School A Teacher 1 felt many other subjects would take priority over Classics.

2. Do you think Classics (including languages) could be incorporated into a current topic area on the NIC?

All teachers said this was an option because of a natural connection to WAU. Both teachers in School C connect Classics to Literacy and Numeracy in their ‘The Romans’ topic. Teachers 1 in Schools A and B also suggested cross-curricular links to Numeracy.

Schools B and C Teachers 2 argued that language learning could link to speaking and listening aspects of the Literacy component on the NIC.

3. What support would you need to progress the development of Classics in your classroom?

Teachers 2 in Schools B and C as well as Teacher 1 in School A all posited that teacher training would be paramount.

School C Teacher 1 emphasised that training was not necessary but suggested there should be closer university-to-primary-school links that could facilitate external visitors as well as providing hands-on resources and artefacts.

School A Teachers 1 and 2 alongside School B Teacher 1 all believed that resources were essential, including online resources and advice on how to utilise them.

All teachers highlighted that Classics could be incorporated as part of a club after school. School C Teacher 2 emphasised a need for external agencies and school trips to encourage enthusiasm for the subject.

Focus Group Results

Initial questions to assess children's knowledge of Classics

1. What classical subjects or topics have you learned before?

In Primary Six, the children stated they learned about Pompeii during a topic on volcanoes. Child G pointed out that they learned about the excavation of Pompeii as well as the eruption of Mount Vesuvius.

Child C stated that in Primary Seven they learned Latin.

2. Was that the first time you had ever learned them in school?

Child C said they had never had any experience of Classics prior to Primary Six.

Most children wanted to learn more about the Romans in future. Child E wanted to learn about the Greek gods, stating, ‘I think they're really cool and we didn't get to learn about them before’.

RQ1: Benefits of learning Classics

1. What was the best thing you learned when you studied Classics?

Most children enjoyed the experience of comparing life today to Ancient Rome. Children B, D, E and F enjoyed Latin. Child D liked ‘Latin because we got to hear how they spoke back then’.

Most children preferred the study of language (Latin) to their Pompeii focus (Ancient History). Child C preferred History and thought Latin was a ‘dead language’.

2. Do you think Latin would be useful to help you learn English?

All children agreed that it was helpful to learn new vocabulary words. Child D stated, ‘It meant we could learn it through something fun rather than just learning it because we have to learn it, like for spellings’.

3. Do you recognise these characters?

The children were shown five different coloured prompt cards, each a different character from modern stories and movies. The characters were all linked to the classical world (characters included: ‘Fluffy’ the three-headed dog from the Harry Potter series based on Cerberus the hellhound; ‘Harry Potter’ with a Latin speech bubble from the Harry Potter series; the gods of Olympus from Disney's Hercules; Mr Tumnus the fawn from the Chronicles of Narnia; and the characters from the Greek myths retelling Percy Jackson series). These prompt cards were chosen to ascertain if the children could link their popular culture knowledge to their understanding of the classical world. The children were able to identify all characters on prompt cards. Child E was able to link the characters on the Hercules card to the Greek gods and mythological characters.

4. Do you think they are connected to classical subjects?

All children felt that they could connect the characters to Classics. Some children discussed the Latin used in Harry Potter for their spells. Child H used the Latin word canis (dog) to identify ‘Fluffy’ the dog from Harry Potter.

5. Do you think it would be a good thing if you studied Classics to help you understand these stories more?

All children felt that it would help them understand the stories more. Child C explained that by learning Latin, they would better understand what the spell was doing. Child E said it would help to understand why we still have these stories.

RQ2: Challenges of learning Classics

1. What was the hardest thing you learned when you studied Classics?

Children A, B and C found pronouncing Latin words hard, making it hard to remember. Children G and H preferred writing Latin as a result.

All children considered it good to find things difficult; Child G explained, ‘The harder it is to do it, the more you want to do it’.

2. Is there anything you did not like about the subject?

Child A stated that they did not enjoy Classics because they found the history confusing. Most children enjoyed Classics in general.

3. How important do you think Classics is as a subject for children your age to learn?

Child C did not consider it very important as they may not study it in post-primary. Child B added that if teachers did not know about the subject, then they would not need to know it either. Children E and G believed it was very important to learn about it for future jobs and general knowledge.

RQ3: Future Development in learning Classics

1. If you could design your dream school timetable, would you get to learn a classical subject?

Most children wanted it on their dream timetable. Child C said there would not be any point ‘because it's dead’. Child H wanted to learn it because Latin helped them learn new English words.

There were varied responses as to how often they would learn it ranging from ‘never’ to ‘once a day.’ Child E identified cross-curricular links, stating it could be studied once a day through different contexts. Child C also explained that their knowledge of Pompeii was developed during a topic on volcanoes.

2. Is there anything teachers could do to make the subject important for children to learn?

Some children felt that teachers needed to be taught how to teach Classics as well as understanding that it was a subject their pupils enjoyed. Child G suggested that if languages in general were promoted like Spanish and German, then Latin could also be promoted.

Analysis and Discussion

RQ1. What benefits, if any, does Classics bring to Northern Irish primary teachers and pupils?

Connections to MFL and Inclusion of Newcomer Children

School A Teacher 1, although admitting they had little understanding of classical languages, explained: ‘I would assume you would have the same breakdown of word structure … it would provide a deeper understanding of how [MFL] work’. School C Teacher 2 found it ‘very important to see that all these foreign languages have developed from Latin and Ancient Greek’.

Child G was an advocate for learning MFL: ‘If we got to learn other languages in school like German or Spanish, then maybe we could learn more Latin’. This demonstrates a pupil-led desire to learn languages and so the route to develop primary classical languages may be to encourage MFL study.

Across all schools, the majority believed that the introduction of a classical language would promote integration of a newcomer child, although it was not a priority. School A Teacher 1 expressed: ‘I can see right away that you are putting the EAL child on the same grounding as everyone else because suddenly you're all learning a new language together’. Albrecht (Reference Albrecht2012) reports positive outcomes for Turkish newcomers, so this is certainly worth exploring further.

Additionally, School C Teacher 2 suggested a newcomer child's language development could be supported by Latin, promoting both Language 1 (L1) and Language 2 (L2) learning. The teacher then suggested that this ‘would work in a triangle; the Latin links to the English, the Spanish links to the Latin and with that then the Spanish and the English are connected’.

This triangle analogy (see Figure 2), explored by School C Teacher 2, has implications for policy development in NI as, with 11,964 newcomer primary pupils and the ambitions of the Every School a Good School document, it is paramount that these children are enabled to develop their L1 and L2 proficiency whenever possible (DENI 2009, 2020, 2022).

Figure 2. The triangle analogy.

Literacy Attainment

All teachers within this study agreed that there is a strong connection between learning Latin and English literacy development, with some specifically mentioning Latin's ability to enhance English vocabulary. School A Teacher 2 commented: ‘It would help children to understand word meanings by making connections with classical vocabulary and roots of words’. Within the focus group, the children found Latin enhanced their vocabulary: ‘The word ‘vale’ is actually in the word valediction, so it comes from it’ (Child D).

Conversely, in School C, Teacher 1 added they ‘wouldn't say as a whole, using Latin or Greek would help people learn the English language … it has a place and that would come later’. In line with other teacher opinions, this teacher suggested etymology was a useful strategy when teaching Key Stage 2 children specific spellings but had to be used effectively.

Cross-curricular benefits and twenty-first century skills

Although acknowledging cross-curricular links between Classics and the NIC, School A Teacher 1 commented, ‘I think there are things with more pressing demands, like ICT and things that will be more relevant for the jobs of the future’. Teacher 2 in School A partially agreed but suggested that teachers could use ‘computer games and apps to promote learning’ to combine both the teaching of Classics and of twenty-first century skills, thereby providing a clear link ‘to the Thinking Skills and Personal Capabilities (TSPCs) components’ of the NIC.

Holmes-Henderson and Tempest (Reference Holmes-Henderson, Tempest, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) argue that Classics facilitates the development of twenty-first century skills, including communication. In Schools B and C, Teacher 2 noted that implementing classical languages could boost children's speaking and listening skills, a requirement of CCEA (2007).

With experience of teaching the topic ‘The Romans’, School C Teacher 1 stated, ‘“The Romans” allows the Northern Irish curriculum to work because it's such a broad topic to use’. This teacher currently links ‘The Romans’ to WAU, Literacy, Numeracy and Personal Development and Mutual Understanding (PDMU), thus showing the extent of cross-curricular relevance Classics can offer. Children also identified the cross-curricular links as Child E commented, ‘I think you could do it lots because you could do Latin in Maths, like with Roman Numerals’.

Connections to Popular Culture and Cultural Appreciation

This study identified links between Classics and popular culture, although the connections highlighted by teachers differed between schools. Within School A, teachers discussed the potential for children to compare the ancient and modern worlds, exploring influential art, and literature. Teacher 1 suggested ‘you could compare the myth of Hercules to an Irish myth’ which would in turn develop children's ability to see correlations between different mythologies and histories (Bloor et al., Reference Bloor, McCabe and Holmes-Hendersonforthcoming; Holmes-Henderson and Tempest, Reference Holmes-Henderson, Tempest, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018).

Teachers and pupils in School B discussed film culture. Teacher 2 suggested, ‘Disney's Hercules … it might make them appreciate the movie and its historical or even mythological background all the more’. As Beard (Reference Beard, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018) posits, such movies have generated a rise in classical awareness. Both teachers believed that using these movies may generate a new interest for children. Child C also considered popular culture as they would ‘listen more to what the spells are doing in Harry Potter because he's using Latin’. In this way, films that incorporate classical themes could be used to promote engagement in Classics and raise awareness of its use in popular culture.

Within School C, the focus lay in the relationship between Classics and cultural appreciation. Teacher 2 explained ‘As a society we tend to have people of different religions and ethnicities’. Teacher 1 discussed the idea of ‘common heritage’ in relation to ‘The Romans’: ‘We spoke about how, say, in Britain at the time of the Romans there would be this diversity that would've existed … there would've been a multi-cultural, multi-racial society’. Moving forward, using Classics to appreciate cultural differences will aid in the implementation of the Every School a Good School policy (DENI, 2009).

RQ2. What challenges do teachers and pupils face in Northern Ireland in trying to implement Classics in their classroom?

Time Constraints

In School A, Teacher 1 suggested that ‘Due to … curriculum time constraints it [Classics] would be very hard to support’; but, as stated previously, the NIC is built upon cross-curricular thematic frameworks, and so Classics could be implemented into other sections of the curriculum. Child E supported this by stating, ‘like with Roman numerals and stuff…you could very easily do it once a day’, thus showing that children's enthusiasm for the subject prompts them to find solutions to the problem.

Teacher Awareness and Subject Knowledge

Studies show that teachers are nervous about teaching Classics due to lack of historical or linguistic subject knowledge (Bell and Wing-Davey, Reference Bell, Wing-Davey, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018). In School C, Teacher 2, having taught a ‘Romans’ topic, explained that, in terms of teaching Latin, ‘I wouldn't be confident, though, in teaching it as an extended topic’. Furthermore, School B Teacher 1 suggested that it was teachers' lack of knowledge of the benefits of Classics that hindered its progression: ‘We don't know why we would do it’. The focus group made the link between pupil enjoyment and the need for teacher training. Child E explained: ‘Teachers could be taught that we want to learn it, then they could teach it to us so it wouldn't be dead’. In this way, opportunities for teacher training arise.

RQ3. What future development is possible for Classics in Northern Ireland?

Teacher Training and Support

In this study, most teachers agreed that teacher training was important to promote Classics and highlight its contributions to the primary curriculum. In School B, Teacher 2 commented that if teachers ‘don't have that knowledge or see how you could link it to the curriculum well then they wouldn't see it as relevant’. Training is important to dispel potential fears in teaching Classics as outlined by Bell and Wing-Davey (Reference Bell, Wing-Davey, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018). Holmes-Henderson (Reference Holmes-Henderson2016) found that 70 per cent of teachers who attended a primary Classics training day stated that they would be likely to implement Latin into their classroom as a result.

In School A, Teacher 1 noted that, regarding training and resources, they had ‘never been made aware of it…not even through my teacher training’. By contrast, School C Teacher 1 felt they were equipped to teach ‘The Romans’ as they explained: ‘for the two, three years I was learning to teach, there was an expert that I was able to pull upon and say “How do you do this?”’. An intervention during Initial Teacher Education (ITE) would be beneficial to promote Classics in primary schools. As noted through a case study by Poulter (Reference Poulter2018) where students in ITE were 'upskilled' in Latin and asked to teach a primary workshop, student teachers can identify multiple benefits of teaching Latin when supported with appropriate training.

Using Latin to Challenge

Although some teachers believe Latin is too challenging for all pupils (Holmes-Henderson, Reference Holmes-Henderson2016), this study found that teachers saw the challenge as beneficial. In School 1, Teacher 2 noted that classical languages could be used as an extension for ‘more able learners’. For example, in School B, Teacher 1 used Ancient Greek for their ‘top spelling group … we would talk about where words come from’. Similarly, in School C, Teacher 1 suggested that Latin became most helpful when teaching ‘higher-attaining children when discussing things like morphology and etymology of words’. When asked about the concept of challenge, Child A said that ‘It's good to find things hard because that's when you learn’. While the teachers and pupils made important points, the authors believe that Latin or Ancient Greek should be accessible to all pupils within a learning context, be it at primary or post-primary level (as Beard Reference Beard, Holmes-Henderson, Hunt and Musié2018 encourages).

Conclusion

Key Findings

RQ1. What benefits, if any, does Classics bring to Northern Irish primary teachers and pupils?

All participants agreed that learning a classical subject offered benefits, irrespective of the prior classical experience of the teacher. These benefits included: the relationship between MFL and Latin, the potential to strengthen literacy attainment, the development of cultural awareness (popular culture or historical) and flexibility with respect to cross-curricular links. To become aware of these benefits, it was generally agreed that primary teachers should receive content and pedagogy training for Classics. Most children in the study felt that Latin helped them to develop a deeper understanding of English. They stressed that teachers should be informed of how much they enjoyed Classics and highlighted that Classics could be utilised across the curriculum.

RQ2. What challenges do teachers and pupils face in Northern Ireland in trying to implement Classics in their classroom?

There was a perception that Classics could be considered irrelevant and thus hard to promote in a school unless the subject was presented meaningfully to teachers. Some teachers expressed a lack of confidence in teaching the subject, stating that others may feel the same, thus potentially generating fear of the subject. Curriculum crowding was raised as a barrier to expansion in Northern Ireland, with teachers instead prioritising Literacy and Numeracy.

RQ3. What future development is possible in Classics in Northern Ireland in order to make it relevant and sustainable?

Most participants considered teacher training necessary. This training would not only increase knowledge and dispel any ‘subject fear’, but also enhance the understanding of the benefits that Classics could offer children. The focus group supported this position and added that teachers ought to be told Latin is a subject that children enjoy learning.

Limitations

This was a small-scale study, with limited data collected. To gain a better perspective of the attitudes to Classics across NI, a larger sample size should be used. A larger scale study could incorporate more interviewees and questionnaires to identify the level of classical subjects or topics being taught, as well as a more representative view of educational professionals across the country.

In future, it would be advantageous to use random sampling of pupils across a variety of schools to enhance reliability. Engaging with more pupils in focus groups will provide a clearer picture of pupil perspectives. To gain a deeper understanding of how children view Classics, children could be interviewed before and after learning a classical topic, improving the robustness of the study design.

Recommendations for Future Research

This study has highlighted the importance of research in the relationship between learning MFL, Latin and English and how, in particular, newcomer children are positioned within this complex language education nexus. It would also be interesting to research, in a Northern Irish context, how teaching a classical language might influence Literacy attainment, especially to boost English vocabulary, in line with Every School a Good School (DENI, 2009) and Count, Read, Succeed (DENI, 2011) policy aims.

Finally, a study of how Classics develops as a cross-curricular unit for the NIC will be important. ‘The Egyptians’ is a commonly taught topic within Northern Irish primary schools, so teachers are clearly already persuaded by the relevance of (some) ancient history. It will be interesting to discover more about why and how ‘The Egyptians’ has succeeded as a cross-curricular unit. We hope that this approach could be extended to the ancient Greeks and Romans via ready-made materials.

Recommendations for Policy and Practice

These findings shed new light on teacher and pupil experiences of Classics in primary classrooms in Northern Ireland. Expansion could be achieved simply and quickly by celebrating the cross-curricular nature of Classics and providing guidance and support materials to teachers on how to utilise the subject across many curriculum areas of the NIC.

For professional practice in primary schools to change, teacher training in Classics (inclusive of both languages, Classical Civilisation and Ancient History) must be made available to teachers in both school and in ITE, in the form of workshops or modules. This training should offer both the ability to 'upskill' in Classics, as well as provide clarity on how to introduce it at primary level. Currently, student teachers with an A Level qualification in a classical language have the option to join similarly qualified modern linguists taking a specialist pedagogy module ‘Languages in Schools’ on the BEd programme at Stranmillis University College. In addition, they may choose to undertake a research dissertation study reflecting on an aspect of relevant policy or classroom practice; however, the lack of Classics teaching in schools and the absence of statutory policy explicitly naming Classics means that numbers on this BEd route are low.

In recent years, and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, the Classical Association in Northern Ireland has supported teachers who wish to introduce Classics to their schools and holds termly talks and lectures from academics across the UK. There is a great deal of goodwill from the Classics community to widen access to the study of the ancient world in schools in Northern Ireland but a policy intervention is needed.

In an education system where the needs of pupils are paramount, it is important to consider what the study of Classics ultimately offers. School C Teacher 1 was clear: ‘As a subject, the children love it…oh they really, really do’. But in our view, Child D sums it up best, ‘We were really lucky to get to learn it … if more schools taught it then everyone could be lucky’.