In the latest version of the DSM, the DSM-5, 1 a dissociative subtype of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is included. Patients with this dissociative subtype meet the full criteria for PTSD and, in addition, show persistent or recurrent symptoms of dissociation. These symptoms may take the form of depersonalisation, i.e. experiences of feeling detached from one's body (e.g. like watching yourself from the outside); and/or derealisation, i.e. experiences of unreality of surroundings (e.g. the world around you is experienced as unreal or dreamlike). The addition of this dissociative subtype was partly based on the neurobiological finding that patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD show midline prefrontal inhibition of limbic regions that are involved in emotion regulation, leading to emotional overmodulation. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner2

With respect to the clinical implications of the addition of the dissociative subtype to the DSM, it was assumed that patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD, on the basis of these impaired emotion regulation capacities, are not indicated for trauma-focused treatments (TFTs) such as prolonged exposure (PE) or eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy. Reference Lanius, Brand, Vermetten, Frewen and Spiegel3 These TFTs typically activate the fear network and are aimed at emotional processing of trauma-related information within that network. For patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD, it was assumed that the ability to adequately activate the fear network would be limited owing to emotional overmodulation, and that, as a result, TFT could not be effective. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner2 Instead, clinicians were advised to provide these patients with a phase-based treatment approach, in which they learn to better regulate their emotions before they enter TFT. Reference Lanius, Vermetten, Loewenstein, Brand, Schmahl and Bremner2 Correspondingly, many clinicians hesitate to provide TFT to individuals with PTSD who have dissociative symptoms. Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson4 Presumably, this contraindication would apply even more to patients with severe mental illness, for instance, PTSD patients with psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. These disorders are characterised by delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech, disorganised behaviour and negative symptoms. Although dissociation and psychosis are related and are interactive symptom domains, Reference O'Driscoll, Laing and Mason5 the typical characteristic of severe impairment in reality testing in psychosis is not a feature of dissociation. Having clinically relevant dissociative symptoms in addition to psychotic symptoms may lead to even more reservations among clinicians regarding the use of TFT in these patients. Thus far, however, there is a lack of clinical studies into the effects of TFT on patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD in patient populations with severe mental illness.

Method

In this brief report, we want to address this topic by comparing patients with psychosis with and without the dissociative subtype of PTSD, who underwent TFT without any pre-phase of emotion regulation skill training. We performed a secondary analysis of a large randomised clinical trial among PTSD patients with psychosis (for details, see de Bont et al Reference de Bont, van den Berg, van der Vleugel, de Roos, Mulder and Becker6 ), comparing 8 sessions of TFT – either PE (n = 53) or EMDR (n = 55) therapy – with waiting list (n = 47) for PTSD patients with psychosis. In earlier papers, we have reported that TFT was more effective than waiting list in primary (PTSD symptoms) Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh and Van Minnen7 and secondary (psychosis and depression) Reference de Bont8 outcomes, and that TFT did not lead to adverse events or symptom exacerbations in this patient population. Reference van den Berg, de Bont, van der Vleugel, de Roos, de Jongh and van Minnen9

To test the assumptions above, we compared effects of TFT for patients (PE and EMDR combined; n = 108) with and without the dissociative subtype of PTSD, as established with items 29 (derealisation) and/or 30 (depersonalisation) (frequency ⩾1 and intensity ⩾2) on the clinician-administered PTSD scale (CAPS). Reference Blake, Weathers, Nagy, Kaloupek, Gusman and Charney10

The trial design was approved by the medical ethics committee of the VU University Medical Center and was registered at isrctn.com (ISRCTN79584912).

Results

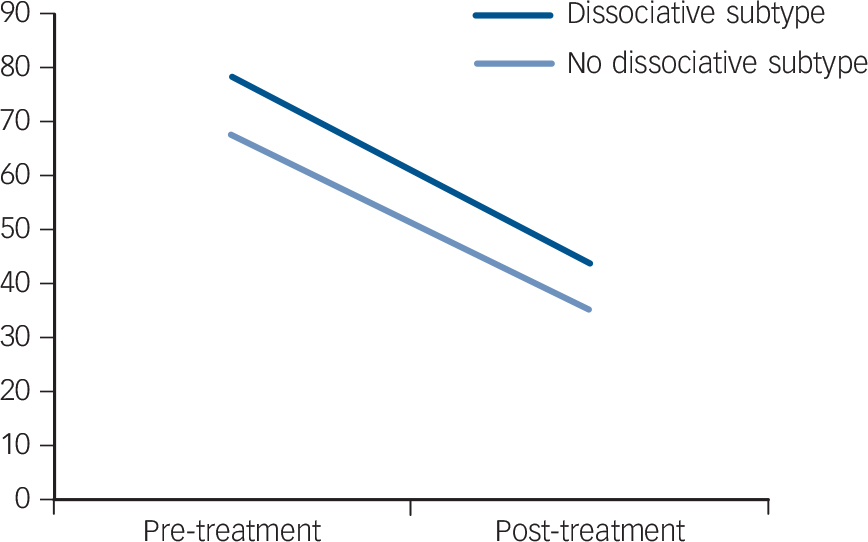

We found that 24.1% of our population fulfilled the criteria of the dissociative subtype, a proportion comparable with other studies. Reference Lanius, Brand, Vermetten, Frewen and Spiegel3 All patients fulfilled diagnostic criteria for a psychotic disorder (60.2% had schizophrenia and 29.6% schizoaffective disorder) and full diagnostic criteria for PTSD. Most patients had experienced severe childhood trauma. In the PTSD, dissociative subtype group, 7 patients dropped out (26.9%) v. 17 patients (20.7%) in the PTSD no-dissociative subtype group (χ2(1, n = 108) = 5.08, P = 0.59). The following analyses were performed in the subgroup of completers (n = 82; post-treatment data were missing for 2 treatment completers). Patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD showed a similar decrease in PTSD symptoms on the CAPS (within-group Cohen's d = 1.63) to that of the patients without the dissociative subtype of PTSD (within-group Cohen's d = 1.68), with large reductions observed in both groups (see Fig. 1). Patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD showed significantly more severe PTSD symptoms at pre-treatment (t(80) = −0.29, P = 0.005), whereas at post-treatment, CAPS scores did not significantly differ (t(80) = −1.34, P = 1.85).

Fig. 1 CAPS (clinician-administered post-traumatic stress disorder scale) scores for patients with (n = 18, 22%) and without (n = 64, 78.0%) dissociative subtype in completers.

Discussion

Our data showed that even in one of the most vulnerable patient populations – patients with a psychotic disorder and PTSD – individuals with the dissociative subtype of PTSD showed large improvements in PTSD symptoms and responded in a similar way to those without the dissociative subtype of PTSD. Our data are in line with several other studies in other patient populations (e.g., Wolf et al Reference Wolf, Lunney and Schnurr11 ) and thereby add to the consistent findings that patients with dissociative subtype benefit from TFTs comparably to patients without this subtype. Also, patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD did not drop out more often than patients without the dissociative subtype of PTSD, suggesting that TFT is not intolerable for PTSD patients with dissociative subtype.

Our study needs replication in this specific patient population, especially because symptoms of psychosis and dissociation are highly related Reference O'Driscoll, Laing and Mason5 , and more sophisticated measures of dissociative subtype could be used in future studies. Despite these limitations, however, our data strongly indicate that there is no need to withhold patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD from TFT, or to add a pre-phase of emotion regulation skills for patients with this subtype. Together with the many recent and consistent findings that patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD respond equally well to regular TFT as do patients without the dissociative subtype of PTSD (e.g. Wolf et al Reference Wolf, Lunney and Schnurr11 ), this study showed that patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD do not need a different treatment (see also De Jongh et al Reference De Jongh, Resick, Zoellner, van Minnen, Lee and Monson12 for a similar discussion). For clinicians, it may be valuable to know that, in contrast to their clinical view, Reference Becker, Zayfert and Anderson4 patients with the dissociative subtype of PTSD can be effectively and safely treated with prolonged exposure therapy or EMDR therapy, using standard treatment protocols without preparatory emotion regulation skill training.

Funding

This study was funded by the Dutch Support Foundation ‘Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ’, P.O. Box 9219, 6800 HZ Arnhem, +31(26) 38 98900, E-mail: [email protected] (awarded to M.v.d.G.). Stichting tot Steun VCVGZ had no part in the design and conduct of the study or decisions about this report.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.