I. INTRODUCTION

We apply the Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM) framework in linguistics to a semantic and textual analysis of the core concepts and economic principles in Chapter III of the Wealth of Nations. The title for Chapter III articulates Adam Smith’s famous proposition “that the division of labour is limited by the extent of the market” (I.iii; sources of cited quotations are taken from Smith [1776] Reference Smith1981). To non-experts in economics, non-native speakers of English, or anglophone economists who are unfamiliar with eighteenth-century King’s English, Adam Smith’s proposition may be unclear, imprecisely translatable, and somewhat ambiguous to modern readers.Footnote 1 What do the “division of labour” and “the extent of the market” mean to a first-year student in economics? If “it is the power of exchanging that gives occasion to the division of labour,” what does “exchange” mean (I.iii.1)? Except for a tiny minority of scholars, most economists do not use such terms in their professional writing, and first-year students of economics almost surely never hear such phrases except if they happen upon a sentence or two of Adam Smith.

Moreover, there is a danger that when we encounter such terms as “the market” or “industry,” we imbue them with twenty-first-century meaning that would be foreign and hence unrecognizable to eighteenth-century readers.Footnote 2 Both conceptually and semantically, these terms are anything but simple and intuitively clear; they are, on the contrary, demonstrably complex (i.e., based on a combination of simple and complex meanings) and potentially obscure. To be interpreted precisely, these words in the original eighteenth-century text need to be carefully decomposed and elucidated with a semantic analysis based on precise criteria.

We produce explications of Adam Smith’s famous proposition that are clear, cross-translatable into any language, intelligible to a twenty-first-century reader, and faithfully close to the original text. Following Smith’s line of argument, we examine the semantics of four important principles in Chapter III: (i) more people choose to live in places where there are more opportunities to exchange things; (ii) the possibility of exchanging many more things in places where many people live favors a greater division of labor in these places; (iii) the practice of exchanging things connects people living in places very far apart and consequently fosters international relations; and (iv) there exists an intrinsic distinction between places based precisely on the extent to which the exchange of things and the division of labor are developed. Our aim is to lay bare the semantic, conceptual, and logical relation between these principles by showing that the fourth one derives from the first three. At the same time, we show that it is possible to pinpoint the semantics of these principles in a clear and precise fashion only by referring to the core principle expressed in the Plan of Work in the Wealth of Nations whereby, according to our semantic analysis, “all people want to have some things to live well and to feel good.”

When we embarked on this project, we had two main criteria in mind: semantic transparency and cross-translatability. Imagine what would happen if the same text written by Adam Smith could be read in precisely the same way by speakers with many different linguacultural backgrounds. This means going beyond mere translations and producing a completely new text that is simpler and more intuitive, and, more importantly, that can be read in any language without having to make all the necessary adjustments for the benefit of the target readers. To produce such a text, it is necessary to stick as closely as possible to the original text and pinpoint the core, basic meaning of the moral philosopher’s words without altering their lexical semantics or forcing any interpretation. In addition to textual simplicity and clarity, cross-translatability helps enormously to reduce the risk of interpretive ambiguities and misunderstandings. However simple and clear, a text written in one language may still be subject to distortions and imprecisions resulting from the translation process. By contrast, producing a single text that is not only clear but also immediately cross-translatable eliminates these language-related risks.

The linguistic work on the original text consists in two related activities: first, elucidating the words and concepts in the text that are semantically more obscure, and, second, rewriting the text following the method of reductive paraphrase. This does not mean that in paraphrasing the original text and in reducing it to a (not the) core meaning, we simplify or deprive Smith’s ideas of their analytic rigor and intellectual vein. On the contrary, a clearer text adds greater value to the original by making it immediately accessible to anyone anywhere in the world irrespective of linguistic and cultural barriers. The target readers can read Smith in their native language without anything getting “lost in translation.” Ultimately, not only is a simpler, clearer text highly beneficial and desirable for the sake of semantic accuracy but also for the sake of economics itself.

A work of reductive paraphrase on a text like the Wealth of Nations is also a scholarly challenge. We seek to demonstrate that Adam Smith can be made accessible to a much broader readership. Smith’s ideas can be shared among speakers with different linguacultural backgrounds in line with the truly global view of economics that, we argue, Adam Smith had in mind: economics intended as the science of all people living and doing things with other people. By producing a simple and culturally neutral text that can be read in any language, we demonstrate that Smith’s economic principles are intelligible in every language to both experts and neophytes in economics.

II. METHODOLOGY OF SEMANTIC ANALYSIS

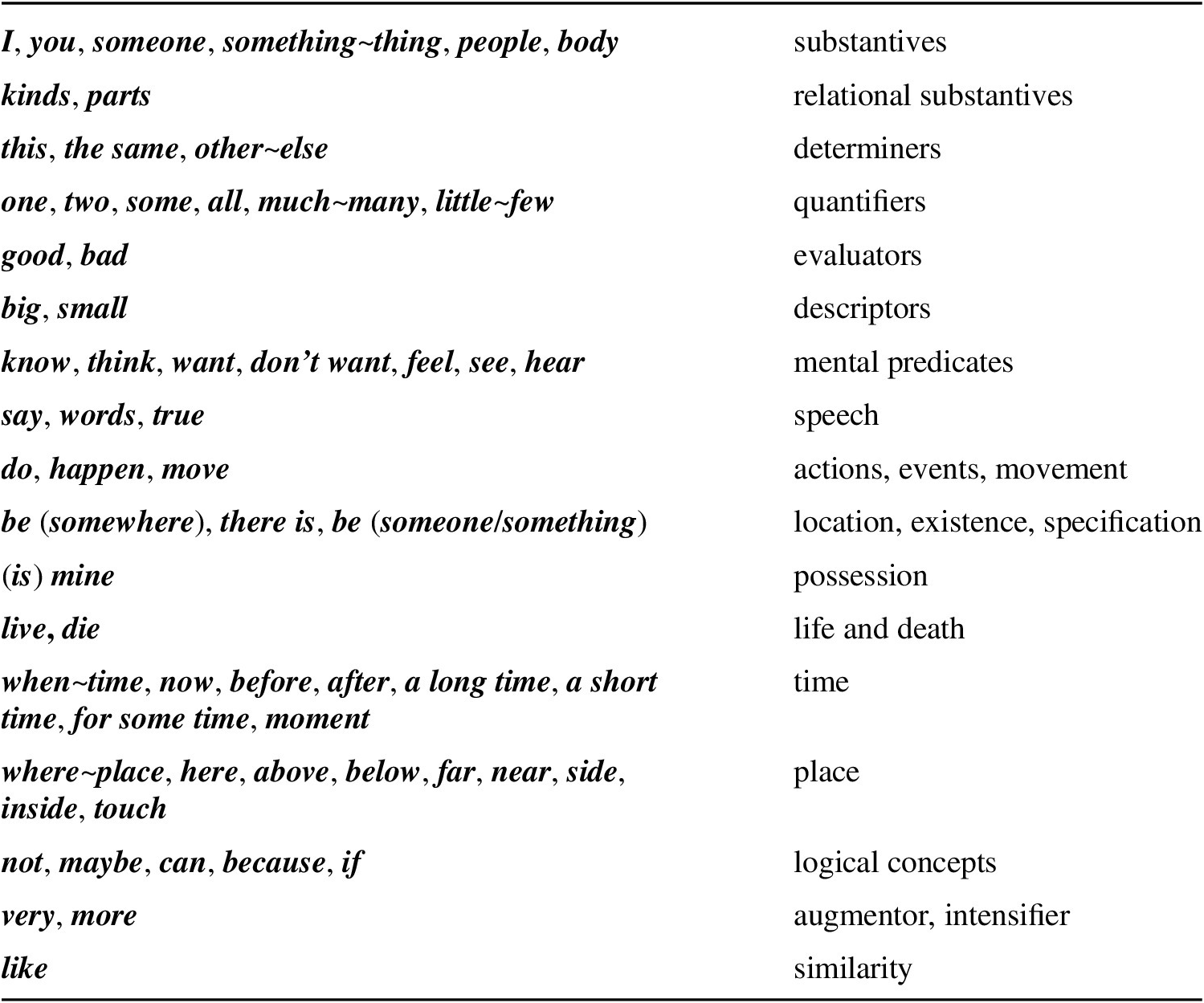

The NSM is a reduced language used to decompose and define the meaning of complex words and concepts. It differs from ordinary languages in that it consists of only sixty-five semantic primes, elementary concepts that represent a semantic core presumably shared by all languages. The criteria for identifying primes are three: (i) a prime is an indefinable concept, i.e., it is impossible to say what it means without ending up with circular definitions;Footnote 3 (ii) a prime is a basic concept, i.e., a concept that cannot be further decomposed or reduced into a simpler concept; and (iii) a prime has a lexical exponent in a natural language that is directly cross-translatable. The NSM was established and fine-tuned over time by the linguist Anna Wierzbicka in collaboration with Cliff Goddard and numerous other researchers from all over the world (Wierzbicka Reference Wierzbicka1972, Reference Wierzbicka1980, Reference Wierzbicka1992, Reference Wierzbicka1996; Goddard Reference Goddard2018; Goddard and Wierzbicka Reference Goddard and Wierzbicka2014). Wierzbicka drew on Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz’s idea that not everything can be explicated; there must be a finite set of basic and indefinable concepts that are presumably innate in human beings and intuitively clear; and these simple concepts are used to explicate all other more complex concepts. This finite set of indefinibilia (called by Leibniz alphabetum cogitationum humanarum or “universal alphabet of thought”) constitutes the mini-lexicon of the NSM. Table 1 presents the English version of semantic primes.

Lexical exponents of the primes have been identified in all sampled languages, but their morpho-syntactic realizations can vary from language to language. The NSM as we know it now has undergone various modifications and updates since its first establishment (Wierzbicka Reference Wierzbicka1972). For example, older versions of the metalanguage included primes that are no longer considered as such and have been eliminated from the list. Two of these are become and have , which have been replaced respectively by happen and be someone’s (mine) as soon as it became clear that these were not semantically simple and, more importantly, not universally available.Footnote 4 In addition to semantic primes, the mini-lexicon of the NSM includes a small group of semantic molecules indicated with [m] (Goddard Reference Goddard2016). These are complex concepts that are decomposable into smaller meaningful units via the primes but used as such in combination with primes to explicate even more complex concepts. Molecules are distinguished according to their degree of specificity. A small number appears to be available in all sampled languages, whereas most molecules are language-specific. Table 2 reports a selection of semantic molecules.

Table 2. A Selection of NSM Semantic Molecules

* Most of these are shared across European languages. Source: Goddard (Reference Goddard2016)

Just as in chemistry, this semantic methodology is based at the same time on both decomposition and composition. Complex meanings are decomposed into more basic primitive concepts or “atoms of meaning.” These, in turn, are combined into molecules and with molecules to explicate the meaning of more complex concepts. To explicate the concepts expressed in Chapter III of the Wealth of Nations, the molecules water, country, and earth are necessary in addition to simple primes. For the sake of simplicity, we employ a “placeholder” exchange. This is a semantically complex concept, but we use it in its non-explicated form to reduce the length of the explications and because the complex concept has been previously explicated (Wilson and Farese Reference Wilson, Farese and Sagarforthcoming). The semantic reason for using exchange in its non-explicated form is that it is the conceptual common denominator of all subsequent explications. Exchange appears consistently in all the explications of Chapter III, which develop from those of Chapter II. It makes sense, then, to use exchange as a placeholder to signal that it functions as the conceptual and semantic reference point for the concepts expressed in Chapter III.

The NSM also has its own simple syntax. Both primes and molecules can be combined in canonical syntactic constructions that are available in all sampled languages, and each semantic prime has specific combinatorial possibilities. For example, the available evidence suggests that the prime do can be used in three universally available syntactic constructions: (i) “someone does something”; (ii) “someone does something good/bad to someone”; and (iii) “someone does something with something/with someone else”/“people do things with other people.” Syntactic constructions that are available in some languages but not in others—e.g., the English idiomatic construction “to do something about something”—cannot be part of the NSM syntax because they are not directly cross-translatable. Consequently, the NSM syntax allows for a limited range of expressive possibilities: it permits the expression of negation (“I don’t want this”/“I don’t know [it]”), of change in time (“a long time before it was like this, it is not like this anymore now”), of contrast (“I want to say it not like I can say it to many people at many times”), and of repetition (“I feel something very very bad in my body”) but does not permit questions (“What is this?”) and the use of conjunctions (“you and I”/“one or two things of one kind”). The mini-language and syntax of the NSM are the only tools we use to produce the semantic explications. An explication typically consists of several lines, single lines being referred to as “semantic components,” and are produced following the method of reductive paraphrase. We have already produced eight explications for the concepts and principles expressed in the Plan of Work and in chapters I and II of the Wealth of Nations (Wilson and Farese Reference Wilson, Farese and Sagarforthcoming). Here we present four other explications, which develop from the previous ones. As the readers will notice, the explications for Chapter III are longer than those for the previous chapters. In the NSM framework, semantic complexity is directly proportional to conceptual complexity. As Smith’s arguments become more and more dense and rich in content, so the explications become gradually longer, reflecting the complexity of the contents and concepts being expressed.

To improve the readability and the flow of the text for our target readers, we make a very minor concession in some cases to the rules of the methodology. The headings of the explications (marked in italics in the text) include both words for semantic primes and molecules and some ordinary words of the English vocabulary (e.g., have, different, work, make, exchange). We made this stylistic choice both for reasons of space (a heading phrased only in NSM would be very long) and for reasons of clarity, so that the reader can know what the content of each explication is simply by reading the heading.

To capture people’s way of thinking in a specific context (e.g., what people think when they exchange things) in a clear and precise fashion, the cognitive scenarios in various explications have been phrased in first- or third-person perspective. It is much easier for readers, we believe, to entertain certain ideas and concepts if these are phrased in terms of “I think like this,” “people think like this,” or “this someone thinks like this.” As well, we use direct speech for interpersonal interactions, and we use the primes good and bad to capture people’s feelings and moral evaluations.

III. EXPLICATIONS FROM THE PLAN OF THE WORK THROUGH CHAPTER II

Adam Smith introduces his project saying:

-

• “The annual labour of every nation is the fund which originally supplies it with all the necessaries and conveniences of life which it annually consumes.” (Plan of Work [PW].1)

-

• “[A]s this produce … bears a greater or smaller proportion to the number of those who are to consume it, the nation will be better or worse supplied with all the necessaries and conveniences for which it has occasion.” (PW.2)

-

• “[E]very individual who is able to work … endeavors to provide, as well he can, the necessaries and conveniences of life.” (PW.4)

From Smith’s diction and repetition on the first page of the book, we conclude that the following is a foundational principle in the Wealth of Nations and more generally in economics (Wilson and Farese Reference Wilson, Farese and Sagarforthcoming):

Plan of Work.1: People want to have things of many kinds to live well and to feel good.

-

(a) it is like this:

-

(b) all people want to live well, all people can feel something good if they can live well

-

(c) because of this, at many times people in many places want things of two kinds to be theirs

-

(d) people want things of one kind to be theirs because they can’t live well if they can’t do something with things of this kind as they want

-

(e) at the same time, people want more

-

(f) they want some things of another kind to be theirs because they want to feel something good

-

(g) they know that they can feel something good if things of this other kind are theirs

We consider this to be a foundational economic principle because the introduction and the entire book rest on this cornerstone. What the explication lacks in expressivity and style, it makes up with plainness and clarity. While the phrase “necessaries and conveniences of life” conveys more than (a)–(g), the semantic explication Plan of Work.1 is nevertheless a correct and simple interpretation of Adam Smith’s opening idea. Moreover, the specific components (a)–(g) are universally human in the sense that they can be translated one-to-one into any language. The seven prior principles from the Plan of Work and first two chapters are (Wilson and Farese Reference Wilson, Farese and Sagarforthcoming):

-

1) Plan of Work.1: People want to have things of many kinds to live well and to feel good.

-

2) Plan of Work.2: People do something for some time and make things.

-

3) Chapter I.1: Different people do different kinds of things. Because of this, they can do much more. It is very good if different people in a place do different kinds of things for some time.

-

4) Chapter I.2: All people can live well because different people do different kinds of things for some time.

-

5) Chapter II.1: All people exchange things of different kinds with other people.

-

6) Chapter II.2: People do different kinds of things because they can exchange things.

-

7) Chapter II.3: People are different because they do different kinds of things, not the contrary.

Note how Smith’s argument flows from the Plan of Work through Chapter II. It begins with the axiomatic cornerstone that (1) people want to have things of many kinds to live well and to feel good. Because people want to have certain things to live well, (2) they do something for some time and make things. When people make things, (3) they do different kinds of things. Because of this, they can do much more, and thus it is good if all people working in a place do different kinds of things. From (1)–(3), Chapter I concludes that it is possible that (4) all people can live well because different people do different things.

To show how (4) is possible, Smith introduces a second axiom: (5) all people exchange things with other people. He is now set to offer his first key proposition: (6) people do different kinds of things because they can exchange things.Footnote 5 The proposition is thus composed of two semantically complex elements: the division of labor (3) and exchange (5). The appendix to this article reports the full NSM explications for these two concepts. Chapter II of the Wealth of Nations concludes with the egalitarian claim that (7) people are different because they do different kinds of things for some time, not because of some difference in natural talent. For Smith, all people in principle have the ability to do something well for some time. These arguments through Chapter II set up the more famous proposition in Chapter III.

IV. FROM “DIVISION OF LABOUR” AND “THE EXTENT OF THE MARKET” TO PEOPLE , LIVE , DO , WANT , AND EXCHANGE

Smith argues that the division of labor and the social practice of exchanging things are interrelated and that their relation depends on—or, in Smith’s words, “is limited by”—a specific variable: “the extent of the market.” Compared with the two previous chapters, Smith’s exposition in Chapter III is not as linear for two main reasons. First, he introduces and discusses a series of key concepts—(i) “the market,” (ii) “the extent of the market,” and (iii) “the improvement of the industry”—without explaining them, presumably taking for granted that these would be intuitively clear to his readers. Second, he makes some implicit distinctions that, for the sake of better textual clarity and intelligibility, need to be made explicit in our paraphrased parallel text. For instance, in stating that “when the market is very small, no person can have any encouragement to dedicate himself entirely to one employment,” Smith presupposes the existence of “small markets” and “big markets” but does not provide a clear example of a “big market,” and neither does he explain what the difference is between the two kinds of market. It is only thanks to a series of specific keywords that this difference can be inferred (reading the text carefully, one cannot help noticing that Smith was meticulous in his choice of words).

Considering that “the market” is the undisputed protagonist of Chapter III, the foremost important question is how to define it semantically. Smith already mentions the term once in Chapter I, but it is only in Chapter III that “the market” makes its first noticeable appearance and is discussed in detail for the first time. Semantically, it is obvious that “the market” could never be defined as “something.” If “the market” were categorized semantically as some thing, then it would be possible to ascribe all the semantic properties of things (both concrete objects and abstract things) to it, but this is conceptually impossible. “Something” or “things” can be conceptually associated with size (“something big/small”), feelings (“someone feels something good/bad”), moral evaluations (“someone does something good/bad”), desires (“I/people want something”), possession (“someone can say about something: this is mine”), functions or purposes (“people can do something with something”), and occurrences (“something good/bad can happen to something”). Significantly, of these conceptual spheres, “the market” is compatible only with size. If not some thing, then “the market” must belong to a different conceptual and semantic category.

The only semantic category that is fully compatible with “the market” is “place.” Not only can places vary in size (“big” or “small”), but above all places are compatible with three key ideas pertinent to economics: (i) sociality (“someone can be in a place with someone else/with other people for some time”); (ii) social activities (“people can do something with other people in a place for some time”); and (iii) people’s wants. This is precisely how “the market” is explicated in Chapter II.1 (see above) with the social practice of “exchanging things” (see the appendix). “The market” is a place where people are often with many other people for some time, where people often do (and say) something with many other people because they want to have some things.Footnote 6 Thus, the market is at the same time a place where people both socialize with others and satisfy their individual needs. We argue that this dual nature of “the market” reflects the dual nature of economics itself as the discipline of the social and of the individual (Smith and Wilson Reference Smith and Wilson2019). Furthermore, considering that the place called “market” performs a specific social function, semantically it is more accurate to classify it as “a place of one kind.” This categorization expressed with the prime kind helps distinguish “market” semantically and conceptually from all other kinds of places that are not associated with specific interpersonal functions.

Classifying “the market” semantically as “a place of one kind” instead of “something of one kind” is crucial for interpreting Smith. In its current figurative use in the English discourse of finance and business (as well as in other languages), “the market” is much closer in meaning to “something” (“the stock market”) to which many good and bad things happen every day (“variations of the stock market”), with which people can do things of various kinds (“to play the stock market”) and about which it is good if people know many things (“stock market tips/consultancy”).Footnote 7 Moreover, the “stock market” is conceived as a somewhat abstract entity that is totally separated from people and in which people participate only passively.

Smith’s use of the “the market” should not be confused with a distinctly modern sense of the term, as in “Health care should not be left to the market” or “Let the market provide the best outcomes.” “The extent of the market” in Chapter III does not connote an extension of the competitive free market system to another economic domain, nor extend the abstract operation of supply and demand to another good or service. Such a sense of “the market” is not tied to a particular physical place. At best, it puts people doing things in the background. At worst, the people drop out altogether.

Even though Adam Smith, too, talked about “the market” figuratively in Chapter III, Smith’s market is conceptually grounded in a real place in the real world, places in the streets of England where people intentionally gathered and socialized to satisfy their needs and wants. Moreover, Smith’s market is based on a real-world activity, the social practice of exchanging things by hand. In sharp contrast to the stock market, people in Smith’s market have an active, not a passive, role. People compose the market. They dynamically shape and mold it according to their wishes and needs. Conceptualized in this way, this real “place of one kind” is directly connected to the very basic principle Plan of Work.1: “people want to have things of many kinds to live well and to feel good.”

Another reason for classifying “the market” semantically as “a place of one kind” is that places, unlike things, are compatible with another key semantic prime: live . The different extents of the market that Smith discusses should not be confused with the different “extents of a place.” There is more to the semantics of “the extent of the market” than the mere geographical factor of area extension. Smith explicitly mentions “populousness” as a determining variable of the “extent of the market.”Footnote 8 In other words, Smith makes a distinction between places where few people live and places where many people live. Importantly, this distinction determines whether individuals will be able to dedicate themselves to a single activity or whether they have to do many activities at the same time.

Thus, it is precisely from this difference in populousness that the first explication of Chapter III needs to start, because this is the first part of the conceptual sequence of Smith’s argument from which all other parts derive. The NSM permits a precise lexical and conceptual distinction between “places where many people live” and “places where few people live,” which is not made explicitly by Smith in the original text. We make it explicit in Chapter III.1(A) (see below) to improve the logical flow of the argument. Since Smith’s main purpose in Chapter III is to create a logical correlation between “the places where people live” and “the things people do for some time,” it makes more sense, we believe, to start from live rather than from exchange. Smith’s point is that living in a place determines the extent to which individuals can exchange things and thus are free to choose what to do for some time, not vice versa. Accordingly, Chapter III.1(A) starts from the idea that “people live in many different places.” The logical connection made by Smith can be captured and expressed much more easily and clearly by using no more than four key semantic primes, people , live , do , and want , plus the semantic placeholder exchange. These five semantic items are sufficient for explicatory purposes and recur consistently in Chapter III.1(A) and (B) below. Other primes are used in combination with these five items to capture a series of differences in quantity ( some - many - few ), subject reference ( some places - some other places ) and activity (“someone does something of one kind for some time not like many other people”). The reason why these explications have not been assigned different numbers is that they mirror each other on the same thematic content and thus can be viewed contrastively. Producing two separate explications facilitates understanding and improves semantic accuracy and comparability:

Chapter III.1(A): Because in places where many people live people can exchange many more things, there are many more people doing different kinds of things in these places.

[A] PEOPLE LIVE IN MANY DIFFERENT PLACES

-

(a) it is like this:

-

(b) people live in many different places

-

(c) in some places there are few people, people in these places can exchange some things of some kinds, not many things of many kinds

-

(d) in some other places there are many people, people in these places can exchange many things of many kinds

[B] WHAT PEOPLE CAN DO IF THEY LIVE WITH MANY OTHER PEOPLE IN A PLACE

-

(e) if people live with many other people in a place, at many times they can exchange many things of many kinds with these people when they want some other things to be theirs

-

(f) because of this, in this place it is like this:

-

(g) very many people can do something of one kind for some time

-

(h) when some people do something of one kind for some time, other people do something of some other kind for some time

Chapter III.1(B) Because in places where few people live people can exchange few things, the same people must do many different things at the same time. Because of this, few people do different kinds of things in these places.

[A] WHAT PEOPLE CAN’T DO IF THEY LIVE WITH FEW OTHER PEOPLE IN A PLACE

-

(a) if people live with few other people in a place, they can’t exchange many things with these people at many times when they want some other things to be theirs

-

(b) because of this, they have to [can’t not-] do many things of many kinds at the same time

-

(c) at the same time, in this place it can’t be like this:

-

(d) many people can do something of one kind for some time

-

(e) when some people do something of one kind for some time, other people do something of some other kind for some time

In Chapter III.1(A), we reconstruct the conceptual and logical sequence of Smith’s arguments in three steps. The first is a premise introduced by component (a) “it is like this,” which in various types of NSM explications presents a specific scenario as a fact, an axiom, or an incontrovertible truth. This is a necessary frame for components (b)–(d), where the difference in the number of people living in different places is related to the possibility of exchanging few or many things of many kinds. We give the prime live intentional prominence both to create a conceptual link with place and to create cross-referencing with the very first explication, Plan of Work.1, which also includes live. The second step is to reference the idea that in places where many people live, there are more chances of exchanging many things of many kinds and therefore people can obtain many more things of many kinds that they want to have (the cross-reference to want , too, is essential). This is captured in (e) by means of a conditional clause introduced by the prime if . The prime kind captures the differences in typology between the things that people exchange and want.

Together, components (b)–(e) elucidate the most important point of our analysis. Semantically, the different “extents” of the market that Smith talks about have nothing to do with the width of the area where people exchange things. They are instead about the different quantities of things of many kinds that people can exchange in different places. Smith argues that since in some places there are many people, those living in such places have more opportunities to exchange many things of many kinds with many people and thus to obtain many more things that they want. It is the prime many that makes the difference, because live , exchange, want , and mine are also part of Chapter III.1(B), which states exactly the opposite. By claiming this, Smith has created a reversible conceptual and logical connection among place , live , exchange, want , and mine . On the one hand, it is place and live that determine exchange, which in turn determines want and mine ; on the other, it is exchange and want and mine that determine live and place , in that more people will decide to live in those places where they know that they can exchange many things and can obtain many things that they want to have. It is precisely on this reversible connection that rest the conceptual and semantic foundations of “the extent of the market.”

Of these three semantic items, the complex concept exchange plays the pivotal role as it represents both the consequence and the cause of the “larger market.”Footnote 9 A “larger market” permits people to exchange and obtain many more things that they want to have. At the same time, having more opportunities to exchange many things with other people encourages more people to live in a particular place, and more people generate a “larger market.” Exchange is also the conceptual basis of the second consequence of people living and doing things with other people in a “larger market”: the fact that “people can do one thing of one kind for some time not like many other people” (not many things of many kinds at the same time) or, in more complex words, a greater “division of labor.”

At this point, a fourth conceptual item, “doing,” becomes part of the intricate web of logical connections created by Smith. Crucially, its relation to the other three is fundamentally one of dependence: “doing something for some time” depends on exchange, want, mine, live , and place . In this case, what people do for some time in a “larger market” is invariably the consequence of the fact that they live in this place, not the cause. Smith is extremely clear about this relation of dependence, so much so that understanding the logical dependence of “doing something” on living, exchanging, and wanting something to be mine determines the correct interpretation of the predicate “is limited by” used in the original title of Chapter III. In this way, Smith categorically excludes that it is the division of labor that determines the extent of the market and argues the other way around. Following Smith’s line of reasoning, in the explication, too, the idea that “very many people can do something of one kind for some time not like many other people” appears at the end as the final consequence of everything that comes before. To reference the “division of labour” and its relation of dependence from place, live, exchange, want , and mine is precisely the third step. Smith’s argument on the extent of the market is not a tautology. The reversible connection of “the extent of the market” is part of Smith’s argument.

Component (f) captures the cause-consequence of (e) and presents a second scenario introduced by the phrasing “it is like this.” Both (g) and (h) are familiar components that already appear in previous explications (see the appendix).

The main purpose of Chapter III.1(B) is to present the differences with Chapter III.1(A). The key point is component (b). As pointed out by Smith, a “smaller market” is much less favorable to the division of labor than a “big market.” Therefore, people living in smaller places have no choice but to (in NSM terms, “they can’t not”) “do many things of many kinds at the same time”:

The scattered families that live at eight or ten miles distance from the nearest of them, must learn to perform themselves a great number of little pieces of work, for which, in more populous countries, they would call in the assistance of those workmen. Country workmen are almost everywhere obliged to apply themselves to all the different branches of industry that have so much affinity to one another as to be employed about the same sort of materials. (I.iii.2)

Noticeably, Smith explicitly contends that when the market is “very small,” the division of labor is virtually impossible. Accordingly, component (c) excludes the scenario that instead is possible in the previous explication (“in this place it can’t be like this” in Chapter III.1[B]). The conceptual differences both within single explications and across explications can be easily identified by looking at specific components. In components (a–d) of Chapter III.1(A), “some places,” “few people,” and “some things of some kinds” are contrasted with “some other places,” “many people,” and “many things of many kinds.” Similarly, component (f) of Chapter III.1(A) is contrasted with component (c) of Chapter III.1(B).

The second part of Smith’s argument is based on the idea that the populousness of a place, which favors the exchange of goods among people and thus the division of labor, depends, in turn, on another determining geographical factor: proximity to the water. Differently from the first part, Smith explicitly distinguishes places near the water from those far from the water:

As by means of water-carriage, a more extensive market is opened to every sort of industry than what land-carriage alone can afford it, so it is upon the sea-coast, and along the banks of navigable rivers, that industry of every kind naturally begins to subdivide and improve itself, and it is frequently not till a long time after that those improvements extend themselves to the inland parts of the country. (I.iii.2)

Although Smith does not mention it explicitly, there seems to be a natural consequence of this distinction in his argument: the possibility of exchanging many more things in places near the water and dedicating oneself to a single activity in these places as opposed to places far from the water makes many more people want to live in the places near the water. A more extended market and a broader division of labor in places near the water attract people to live in these places.

There is an interesting correspondence between Smith’s idea of the beneficial role of water for the exchange of goods and the observations on the “usefulness” of water made by the semanticist Cliff Goddard (Reference Goddard2010, Reference Goddard2016) in his discussion of this semantic molecule. Wierzbicka (Reference Wierzbicka1996, pp. 229–230) defined water [m] as “a particular kind of thing, a kind which we may not always be able to recognize, but which one can ‘put into one’s body, through the mouth’ (i.e., drink it), and which one can ‘see in various places not because people did something in those places.’” Goddard (Reference Goddard2016, p. 26) adds the component “people can do many things with it” to those Wierzbicka posited in 1996, arguing that the “usefulness” of this natural element to serve many different purposes is part of its core invariable meaning.

Goddard’s hypothesis is consistent with Smith’s observations on the advantages of water-carriage. Smith, however, says much more about it. He uses the question of the usefulness of water as the main argument for an economic distinction between places: those that, thanks to their proximity to the water, are more favorable to the exchange of goods and to the division of labor, and those that are less favorable to both because they are far from the water. For Smith, this distinction has implications both for the economy of the respective places and, importantly, for international relations. The latter, Smith argues, tend to be much more florid and prosperous in places near the water:

What goods could bear the expense of land-carriage between London and Calcutta? Or if there were any so precious as to be able to support this expense, with what safety could they be transported through the territories of so many barbarous nations? Those two cities, however, at present carry on a very considerable commerce with each other, and by mutually affording a market, give a good deal of encouragement to each other’s industry. Since such, therefore, are the advantages of water-carriage, it is natural that the first improvements of art and industry should be made where this conveniency opens the whole world for a market to the produce of every sort of labour, and that they should always be much later in extending themselves into the inland parts of the country. (I.iii.3)

Another implication of the distinction between places near and far from the water is the fact that, according to Smith, industries can develop at a faster pace in the former than in the latter. Significantly, Smith does not exclude that industries can improve in inland places, too. He simply asserts that improvement of the industry occurs at a faster pace in places near the water. What “improvement” means, however, remains an open semantic question. It is impossible to pinpoint its meaning without referring to Chapter I, where Smith discussed the various advantages of the division of labor, stating that “it is naturally to be expected, therefore, that someone or other of those who are employed in each particular branch of labour should soon find out easier and readier methods of performing their own particular work, whenever the nature of it admits of such improvement” (I.i.8). In NSM terms, “improvement of the industry” means that if people can do one thing of one kind for some time and not many things of many kinds at the same time, they can do much more (see Chapter I.2) and can do some very good things. We incorporate this idea by positing a composite component (q) that “if at some time before people could do some good things of some kind, after some time they can do some very good things of some kind, not like before.” The primes some , time , before , and after capture the difference in time, and the difference in quality of the products is captured with the primes good , very good , and not like before .

In this case, too, Smith’s distinction can be captured more clearly and precisely by producing two mirrored, comparable explications pertaining to the same thematic area, Chapter III.2(A) and (B) below. The first one is longer than the second one because it includes a semantic paraphrase of the concept and advantages of water-carriage:

Chapter III.2(A): If people live in places near the water, they can exchange many more things. Because of this, in places near the water many more people can do different kinds of things.

[A] WHAT PEOPLE CAN DO IF THEY LIVE IN PLACES NEAR THE WATER

-

(a) if people live in places near the water [m], it is like this:

-

(b) they can do something with something of one kind

-

(c) something of this kind is big, it can move in the water [m] as people want

-

(d) at many times people in places near the water [m] do something with something of this kind when they want some things to be in another place

-

(e) when people do it, it is like this:

-

(f) at one time, many things of many kinds are for some time inside this big thing of this kind, as people want

-

(g) this big thing moves for some time in the water [m]

-

(h) because of this, after some time these things are in another place, far from the place where they were before, as these people wanted

[B] WHAT PEOPLE CAN DO IN PLACES NEAR THE WATER BECAUSE OF THIS

-

(i) because of this, if people live in places near the water [m], they can exchange many things of many kinds with many other people at many times

-

(j) they can exchange many things with many other people in many countries [m] on Earth [m] very far from them if these other people live in places near the water [m]

-

(k) because of this, in places near the water [m], it can be like this:

-

(l) many people do something of one kind for some time

-

(m) when some people do something of one kind for some time, other people do something of some other kind for some time

[C] WHAT HAPPENS IN PLACES NEAR THE WATER BECAUSE OF THIS

-

(n) at all times people in places near the water [m] want to do more, much more

-

(o) because of this, something good can happen in these places after some time

-

(p) when it happens, it is like this:

-

(q) if at some time before people could do some good things of some kind, after some time they can do some very good things of some kind, not like before

Chapter III.2(B): If people live in places far from the water, they can exchange few things. Because of this, there are few people doing different kinds of things in places far from the water.

[A] WHAT PEOPLE CAN’T DO IF THEY LIVE IN PLACES FAR FROM THE WATER

-

(a) if people live in places far from the water [m], they can’t exchange things with many other people at many times like people in places near the water [m] can do

-

(b) they can exchange things with people in places near the place where they live, not in many other places

-

(c) they can’t do much more

-

(d) because of this, in places far from the water [m], it is like this:

-

(e) very few people do something of one kind for some time

-

(f) people in places far from the water [m] can’t do more

[B] WHAT HAPPENS IN PLACES FAR FROM THE WATER BECAUSE OF THIS

-

(g) because of this, something good can happen in these places after a long time, not after a short time

-

(h) when it happens, it is like this:

-

(i) if at some time before people could do some good things of some kind, after some time they can do some very good things of some kind, not like before

Chapter III.2(A) can be divided in three blocks. The first block includes components (a)–(h) capturing the complex concept of “water-carriage,” paraphrased as “what people can do if they live in places near the water.” Here, too, component (a) introduces a specific scenario (“it is like this”) that is exclusive to places near the water. Intuitively, the concept of “water-carriage” may automatically imply that of “boat” or “ship.” However, we don’t use either of these complex non-NSM terms because they are unnecessary to explicate water-carriage. It suffices to mention “something of one kind” that is big enough to carry a great number of goods and that “can move in the water as people want” (component [c]). Human control of the movement of this “big thing” in the water is relevant and hence is part of the explication. Component (d) associates “doing something with something very big” with the specific intention of “wanting things to be in another place.” Components (f)–(h) capture the idea of simultaneous movement of the ship and the goods that it carries inside, the change of location of the goods resulting from movement in the water, and the key point that a larger number of things can be transported to another place if they can move in the water. Being able to transport more things favors the exchange of goods, which favors the division of labor, which, in turn, favors the populousness of a place.

The second block includes components (i)–(m) and brings out the two consequent advantages of living in places where water-carriage is possible (“what people can do in places near the water because of this”). The first is the possibility of exchanging a much larger number of goods and, concurrently, of fostering international relations through trade. Component (i) states explicitly that in places near the water, people can exchange many more things. Component (j) follows the example of London and Calcutta made by Smith and states that through water-carriage the exchange of goods is enabled even between people who live in countries very far away.Footnote 10 The second is the broader division of labor in places near the water (components [k–m]).

The third block, components (n)–(q), incorporates the ideas of “encouragement” and “improvement” of the industry deriving from the possibility of exchanging many more things in places near the water. The core meaning of “encouragement” in (n) is that “at all times people … want to do more, much more.” The remaining three components explicate the meaning “improvement” with the preceding statement that “something good can happen in these places [near the water] after some time” (not “after a long time”).

In general, Chapter III.2(A) emphasizes all the advantages mentioned by Smith by means of intensifiers: many things, many kinds, much more, very many people, and very good. By contrast, Chapter III.2(B) contains a series of negations and diminishers aimed at making the distinction clear: can’t often exchange, can’t do much more, very few people. The key point here is component (b): in places far from the water the market is limited because people living in these places can exchange things only with people in places near the place where they live.Footnote 11 The occurrence of “something good”—the improvement of the industry—is mentioned in Chapter III.2(B), too, but in this case, it happens “after a long time, not after a short time,” as Smith states.

The extent of the market is in this case complemented by the extent of the geographical area that connects people via exchange. The physical costs to moving things determines the extent to which more people live together, even if they are far apart. Smith explains the key proposition in Chapter III by noting how water-carriage has historically allowed more people to live together, even if they are far apart. The key takeaway is that the more people are connected via exchange, the more different things these people can do and the more different kinds of things there will be for them to exchange.

V. CONCLUSION

The Wealth of Nations is about many, many things. But in universally human terms, it is plainly about how all people can live well because people do different kinds of things, and people do different kinds of things because people can exchange things. What limits how well people can live is how many people can do different kinds of things and then exchange these things with other people, so that everyone can obtain the different things they want and need (which is the primary reason for exchanging things). Because in some places people can exchange many more things, there are many more people doing different things in these places. In the natural history of humankind, Smith notes that if people live in places near the water, they can exchange many more things, and because of this, there are many more people doing different things in places near the water. It isn’t an accident of evolution that people live near water. People live near water because they want to have many kinds of things to live well and to feel good.

APPENDIX

Chapter I.1: Different people do different kinds of things. Because of this, they can do much more. It is good if different people in a place do different kinds of things for some time.

[A] WHEN MANY PEOPLE IN A PLACE DO SOME THINGS FOR SOME TIME, THEY DON’T DO THE SAME THINGS

-

(a) when many people in a place do some things for some time, it can be like this: when someone does something of one kind, someone else does something of another kind, some other people do things of some other kinds

-

(b) because of this, they can not-do many things of many kinds at the same time, they can all do one thing of one kind for some time

[B] WHY IT IS GOOD FOR PEOPLE IF THEY DO SOMETHING OF ONE KIND FOR SOME TIME, NOT MANY THINGS OF MANY KINDS AT THE SAME TIME

-

(c) if all these people can do something of one kind for some time, not many things of many kinds at the same time, it can be like this:

-

(d) they can all do something of one kind for some time

-

(e) when someone does something of one kind, this someone knows how to do it well

-

(f) because of this, this someone can do much more during this time

[C] WHEN MANY PEOPLE IN A PLACE DO THINGS OF MANY KINDS AT THE SAME TIME, THEY ALL WANT THE SAME THING TO HAPPEN

-

(g) sometimes, it is like this:

-

(h) many people in a place do things of many kinds for some time, someone does something of one kind, someone else does something of another kind, some other people do some things of some other kinds

-

(i) at the same time, they all want the same thing to happen

-

(j) after some time, it can happen as they all want

-

(k) because of this, it is like this: there are many things there as they all wanted, these things were not there before

[D] IT IS VERY GOOD FOR ALL THESE PEOPLE IN THIS PLACE

-

(l) when all people in a place do something of one kind for some time, not many things of many kinds, they can all do much more during that time

-

(m) this is very good for all people in this place

Chapter II.1: All people exchange things of different kinds with other people.

[A] WHY PEOPLE WANT TO BE WITH MANY OTHER PEOPLE IN A PLACE FOR SOME TIME

-

(a) people know that it is like this:

-

(b) at many times, when someone thinks like this: “I want some things of some kinds to be mine,” not all these things can be this someone’s things because this someone does something for some time

-

(c) because of this, at many times this someone can’t not-be with many people in a place of one kind for some time, they all want some things of some kinds to be theirs

-

(d) when this someone is with many people in this place of one kind, this someone does something with these people

-

(e) people know that after they do this, they can say about many things of many kinds: “this is mine,” not like before

[B] HOW PEOPLE DON’T THINK WHEN THEY ARE IN THIS PLACE WITH MANY OTHER PEOPLE

-

(f) when this someone is with these people in this place, this someone doesn’t think like this:

“I want some things to be mine now, these things are someone else’s things

if this someone can feel something good towards me, maybe this someone will say to me:

‘I don’t want these things to be mine anymore, I want them to be yours’ I want this”

[C] WHEN PEOPLE ARE WITH OTHER PEOPLE IN THIS PLACE, SOMETHING LIKE THIS CAN HAPPEN (IT IS CALLED “EXCHANGE”):

-

(g) when this someone is with these people in this place, this someone says something like this to someone else:

-

(h) “something like this can happen now:

-

(i) I do something good for you, at the same time you do something good for me

-

(j) I can say about some things of one kind: ‘this is mine’

-

(k) you can’t say the same about these things, you want some of these things to be yours

-

(l) if I say: ‘I want this’, some of these things can be yours, as you want

-

(m) this will be good for you

-

(n) at the same time, you can say about some things of another kind: ‘this is mine’

-

(o) I can’t say the same about these things, I want some of these things to be mine

-

(p) if you say: ‘I want this’, these things can be mine, as I want

-

(q) this will be good for me”

-

(r) after this someone says this, these two people say at the same time: ‘I want this’

-

(s) it is good for people when something like this happens

-

(t) all people often do this with many other people in a place, other living creatures [m] don’t do this