Introduction

Participants in health research are overwhelmingly White [Reference Duma, Vera Aguilera and Paludo1–Reference Oh3]. This remains true even when the condition under study is known to disproportionately impact underrepresented ethnic and racial minorities (URM) [Reference Duma, Vera Aguilera and Paludo1, Reference Shin and Doraiswamy4]. The ongoing lack of diversity in biomedical research places unnecessary limitations on our knowledge of human variation and disease, the generalizability of research findings, and our ability to address health disparities [Reference Knepper and McLeod2, Reference Oh3]. It also threatens the ethical principle of justice, which requires that the benefits of research are shared fairly [Reference Bhopal5]. For these reasons, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has established guidelines and requirements to promote the inclusion of minorities in clinical research over the past three decades [Reference Chen, Lara, Dang, Paterniti and Kelly6]. The US Food and Drug Administration has also established guidance to enhance diversity in industry-sponsored clinical trials [7]. Yet, recent studies have shown limited gains in diversity even while the number of clinical trials conducted globally has grown exponentially [Reference Knepper and McLeod2].

The persistence of this problem is also puzzling as the last 30 years have seen the emergence of a large and complex body of literature on the topic of URM recruitment. Participant distrust born of historical research abuse and continued discrimination in clinical encounters has been postulated as a primary cause [Reference Heller, Balls-Berry and Nery8, Reference Corbie-Smith, Thomas and George9]. This work has, in turn, led to the development of a number of evidence-based, frequently community-engaged, approaches to promote the inclusion of URM in clinical research much of which has emerged from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) Consortium members [Reference Ahmed, Young, DeFino, Franco and Nelson10, Reference Sussman, Cordova and Burge11]. These best practices in URM engagement include making use of community partners, community advisory boards, tailored recruitment materials, and the establishment of trust through long-term engagement. Yet, the lack of diversity in biomedical research remains [Reference Duma, Vera Aguilera and Paludo1–Reference Oh3].

In order to assess investigator training needs to support URM recruitment, we conducted a survey of researchers and team members affiliated with the UW-ICTR. Our goal was to explore: (1) attitudes and knowledge about the value of research participant diversity; (2) attitudes and knowledge about the URM best practices described in the literature; and (3) the use of URM recruitment best practices. Our intent was to use this needs assessment to directly inform the development of training programs at our CTSA.

Materials and Methods

We fielded a web-based survey that consisted of items designed to: (1) identify “types” of participants based on role in research, type of research funding, years of experience in research, etc. and (2) determine knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding participant recruitment with a specific focus on URMs. All materials and procedures were approved by the UW Madison Institutional Review Board (#2019–1211).

Items

Items were developed with reference to existing instruments used in similar web-based surveys including the Building Trust Researcher Survey [Reference Quinn, Butler III and Fryer12] and the University of South Carolina Clinical Trials Principal Investigators Survey [Reference Tanner, Kim, Friedman, Foster and Bergeron13]. Adapted questions from these surveys comprised of the conceptual items our instrument that covered knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding URM engagement and best practices. Additional items regarding respondent characteristics (type of research, years in research) were selected from a previous internal UW ICTR evaluation survey of researchers on recruitment practices (not URM focused). The final instrument comprised of 23 items (some including subitems) including those meant to categorize the types of research conducted by respondents as well as to explore training experiences. Additional Likert-type items assessed attitudes and knowledge regarding URM recruitment and general populations “theoretically” (without reference to their own work) and these same attitudes and knowledge items with reference to participants’ specific research activities (e.g., “how much is recruiting racial and ethnic minority participants a priority in your research?”). Likert-scaled items were developed to reflect current best practices in URM recruitment such as community-engaged strategies (e.g., use of community advisory boards, community partnerships, diverse recruitment teams, tailored recruitment methods, etc.) [Reference Heller, Balls-Berry and Nery8]. Once compiled, the University of Wisconsin Survey Center (UWSC) provided an expert technical review of the instrument. Please see the supplementary materials for a copy of the survey.

Survey Procedures

To ensure the impartiality of responses, the UWSC provided oversight of the survey administration which was conducted with Qualtrics survey software. Requests for participation were delivered via email including a personalized link. Three waves of reminder emails were sent to nonresponders. The survey was open for 4 weeks between February 24, and March 20, 2020.

Respondents

Our sample consisted of UW Health and UW Madison current employees who were: (1) users of the UW Madison clinical research management system registered under the title of research coordinator, principal investigator, or co-investigator; (2) users of research support from the UW ICTR between 2017 and 2019; and (3) employees in the UW Madison School of Medicine and Public Health (SMPH) functioning in the role of research coordinator. Emails (1456) were distributed to current employees, which produced 313 participants who finished at least 90% of the survey (response rate of 21.5%). Thirty-four of these respondents were dropped from the analysis because they self-reported not engaging in human subjects research. Data from the remaining 279 respondents were included in the analyses.

Data Analysis

As noted, respondents differed by type of research, research funding, research role, years of experience, and types of participants. Preliminary analyses consisted of comparisons of these groups on variables relative to URM recruitment attitudes, knowledge, and practices. To further these analyses, we constructed two composite scales regarding URM best practices derived from the literature (use of a community advisory board, partnership with community-based organizations, racial/ethnic concordance of research staff and participants, devoting extra time to recruit URM participants, and valuing diverse research participation) [Reference Heller, Balls-Berry and Nery8]. The developed scales were: (1) Best Practices knowledge (seven items; α .907) and (2) Best Practices implementation (five items; α .825). Basic descriptive statistics were computed for the demographic variables, individual survey items, and the two composite scales. Mann–Whitney U tests [Reference Sullivan and Artino14] were computed to determine if there were differences between two groups on our ordinal (Likert type)-dependent variables and t-tests for continuous variables.

Results

Sample Description

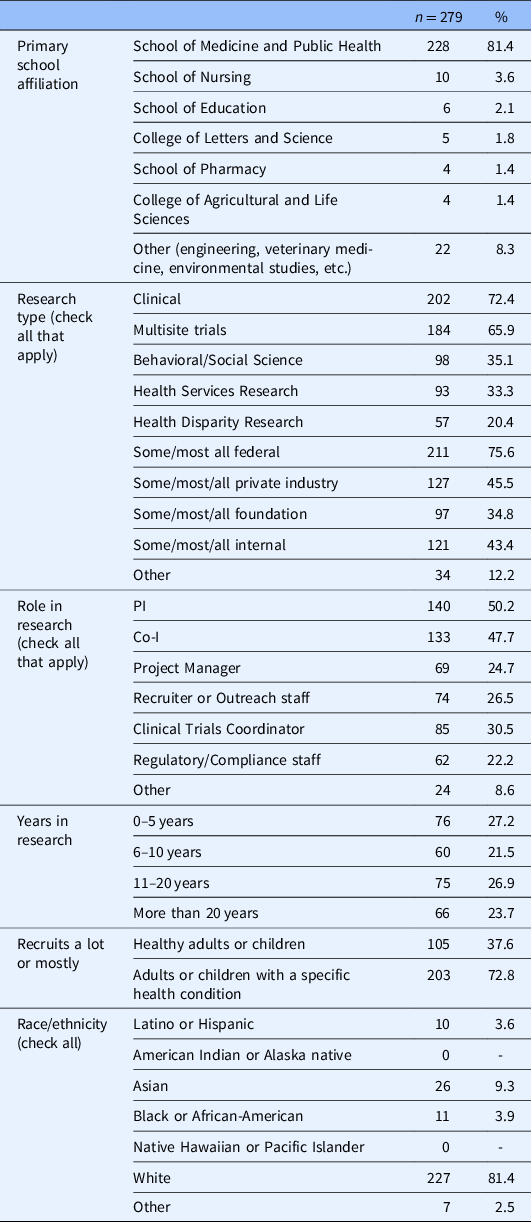

The majority of our respondents were affiliated with the SMPH (81.4%); were engaged in clinical research (72.4%); and recruited patients with a specific diagnosis or condition (72.8%) as opposed to healthy adults (37.6%) (see Table 1). The sample was evenly distributed in regard to respondent years involved in the research. The majority of our sample (75.6%) reported that they received some to all of their research funding from federal sources. Our sample was overwhelmingly White (81.4%), which closely represents the demographic distribution of UW Madison faculty (White; 76%) and noninstructional academic staff (White; 79.8%) [15].

Table 1. Survey respondent characteristics

Overall, respondents had a high level of agreement about the value of diverse recruitment. The majority (87.1%) believed diversity to be very important/extremely important. However, when asked how much diversity was a priority in their specific research program, only 38.3% responded with “a lot” or “a great deal.” This difference was also revealed in the averages of Best Practices knowledge (BP knowledge) and Best Practices implementation (BP implementation) scales which were measured on a 1–5 scale with 5 as the highest. Average scores for these scales were 4.0, 2.9, respectively.

Belief in the importance of diversity in research generally and in researchers’ specific work varied between those with high reported use of federal funding (e.g., NIH) and those with low use of federal funding. Mann–Whitney U tests were computed to examine these differences. There were statistically significant differences between high and low-funding levels on the following items: (1) How important is it that people of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds participate in research? (U = 7858.5, Z = −2.052, P = .040); (2) How much is recruiting racial and ethnic minority participants a priority in your research? (U = 6736.5. Z = −3.139, P = .002); and (3) How much have you worried about your ability to recruit racial or ethnic minority participants? (U = 7014.5, Z = −2.522, P = .012) (see Fig. 1). Reporting of higher use of federal funding was also associated with higher scores on BP knowledge (4.1 vs. 3.8; P=.01) and, to a much larger degree, BP implementation (3.1 vs. 2.7; P < .001).

Fig. 1. Comparison of respondents with high/low reported federal funding on relative “importance” of diversity in research samples.

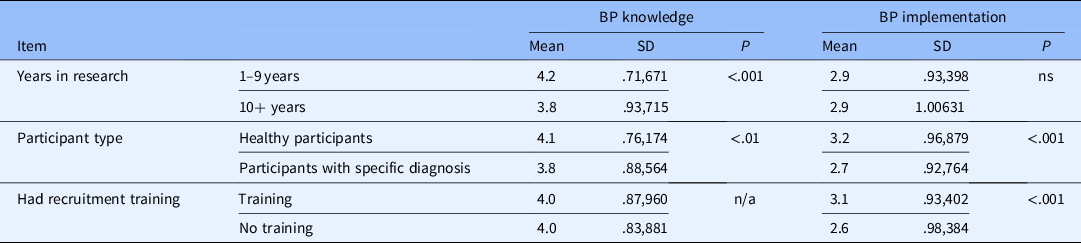

Other groups that scored highly on the BP knowledge scale were those recruiting mostly/all healthy participants and those with less years of experience in research. Those recruiting mostly/all healthy participants were also more likely to implement best practices as were those who reported receiving formal training in general (not URM specific) recruitment/retention practices (see Table 2).

Table 2. Comparisons of best practices (BP) knowledge and Implementation scales

SD = standard deviation.

Discussion

Overall, we identified a high level of abstract recognition of the importance of participant diversity that respondents did not generally see as impacting their individual work either in terms of prioritizing diversity or implementing best practices in URM engagement. There is some variation in our sample, however, that is encouraging. That individual newer to research (less than 10 years of experience) were found to have a greater knowledge of best practices may be an indication of an educational trend toward a greater emphasis placed on the value of diversity [Reference Duma, Vera Aguilera and Paludo1–Reference Oh3]. Similarly, we find that researchers and team members using more federal funding are significantly more likely than others to: (1) believe in the importance of research diversity generally and in their own research; (2) be knowledgeable about best practices; and (3) use best practices in their research. These data suggest that federal efforts to encourage inclusivity in research samples may be contributing to a positive trend [Reference Chen, Lara, Dang, Paterniti and Kelly6]. However, the relatively low implementation of best practices across our sample suggests that, as others have found, efforts are inadequate [Reference Knepper and McLeod2, Reference Oh3].

Although some respondents scored higher on the BP knowledge and implementation scales, our findings point to the existence of an overall gap between the belief in the importance of URM recruitment and the implementation of strategies to improve inclusion in research. Understanding the cause of this gap requires exploration with a larger, representative, perhaps, national sample. However, others have reported barriers caused by researcher and team member perceptions that URM is unwilling to participate, do not typically meet eligibility requirements, make unsuitable research participants, and are not among the clinic population from which samples are drawn [Reference Niranjan, Martin and Fouad16,Reference Durant, Wenzel and Scarinci17]. The reported greater use of best practices for URM engagement among respondents working with healthy participants may reflect the ability to recruit outside of the clinic population.

Finally, the association with training and the reported implementation of best practices in URM recruitment are also encouraging although the percentage of researchers that receive specific training tends to be relatively low [Reference Niranjan, Martin and Fouad16–Reference Niranjan, Durant and Wenzel18]. Trainings include the Building Trust Between Minorities and Researchers curriculum [Reference Hartnett19] and the Faster Together, Enhancing the Recruitment of Minorities in Clinical Trials program. Training programs report increases in self-confidence, communication skills, improved quality of informed consent and, for some, increases in recruitment numbers [Reference Delaney, Devane and Hunter20]. However, rigorous evaluations to include tracking of actual enrollment numbers have been limited to date [Reference Delaney, Devane and Hunter20].

Overall, our findings are mixed. We find evidence of a culture shift toward improving URM research engagement, perhaps stemming from NIH policy. However, researchers still need support in: (1) understanding that the goals of URM inclusion have implications for their specific work; and (2) translating strategies for URM inclusion into active recruitment and retention plans. These data call for education with less emphasis on abstract recruitment ideals and more on concrete ways to connect this knowledge to practice.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this single-site study that impact generalizability. Our goal to guide the development of education programming specifically for researchers affiliated with UW-ICTR, ultimately, limited the reach of our findings. Readers should note that relative lack of diversity in our own sample, which reflects the distributions of race and ethnicity among researchers at our institution but is not representative of other institutions or the researcher workforce nationally. Another study limitation relates to the low response rate. While generally in line with expectations for web-based surveys among samples of health researchers/clinicians [Reference Quinn, Butler III and Fryer12], this low rate limits generalizability. Finally, readers should note that the reported effect sizes, while significant, are relatively small. Nonetheless, we believe that this study provides an indication of an underlying problem in research inclusion that should be substantiated in further studies. Such studies should incorporate rigorous methods and nationally representative samples and be conducted across CTSA hubs or other national research infrastructure networks.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/cts.2020.554.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Ann Sexton and Linda Scholl of the UW ICTR who provided thoughtful feedback on item development along with the Collaborative Center for Health Equity (CCHE) team and the UW Survey Center. Laura Hogan, also of UW ICTR, provided an editorial review. The survey was administered by the UW Survey Center and is financially supported by the CCHE. Our team also received support from the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.