1. Introduction

Opaque prefixed words have been the objects of specific analyses in Chomsky & Halle (Reference Chomsky and Halle1968), using the ‘=’ boundary but, after this boundary was rejected by Siegel (Reference Siegel1974; Reference Siegel, Aronoff and Kean1980), most authors have progressively stopped referring to these units, and those words are often listed among morphologically simple words. In the literature on morphology, the status of historically prefixed verbs such as contain, refuse or submit in contemporary English is a well-known problem (Aronoff Reference Aronoff1976: 55; Anderson Reference Anderson1992: 55; Plag Reference Plag2003: 30–33; Katamba & Stonham Reference Katamba and Stonham2006; Harley Reference Harley2009; Reference Harley2014; Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: 15–16; Mudgan Reference Mudgan, Müller, Ohneiser, Olsen and Rainer2015) because they contain recurring forms with no clearly identifiable meaning, which therefore constitutes a challenge to the standard definition of the morpheme as the minimal meaningful unit.Footnote 1

The aim of this paper is not to discuss how the constituents of opaque prefixed words should be called (formatives, pseudo-morphemes, etc.) but to review different types of evidence that justify their identification as morphologically relevant units, and thus the distinction of those words from morphologically simple words. If opaque prefixed words function like morphologically simple words, then we should expect them to pattern with words with no identifiable structure: their phonological behaviour should resemble that of simplex words and psycholinguistic studies investigating them should report that speakers do not treat them like complex words. Others have developed similar views, relying partly on some of the evidence that we will review (Baeskow Reference Baeskow2006, Harley Reference Harley2009) but our focus is here on the phonological behaviour of such words.Footnote 2 Other kinds of evidence are put forward as corroborating evidence for the analysis that we propose. Another difference with those previous works is that they focus on prefixed words of Romance origin, whereas we include Germanic prefixes such as be- or for- in the analysis. Those have phonological properties that are comparable to Latinate prefixes (detailed in §2.1) but are less common and do not occur in as many forms as Latinate prefixes. The roots found in prefixed words of Germanic origin tend to be free, although there are some bound roots (e.g. begin, believe).

We will start by going through the different types of evidence (phonological, morphological and psycholinguistic) and will show that they strongly support the view that opaque prefixed words are still complex words in contemporary English (§2). Then, we will address the issue of learnability (§3) and the nature of the lexical representations of such words (§4).

Before we begin reviewing the evidence, let us note that not all studies deal exactly with the same type of words. Indeed, the words investigated in the studies reviewed in §2.1 sometimes include items in which the base is free but the following sections in §2 almost exclusively deal with items containing bound roots. As we will see, even among the latter words, there is some variability in the semantic contribution made by the prefix and/or the root which is generally overlooked.

2. Available Evidence Regarding Opaque Prefixed Words

2.1. Phonological evidence

2.1.1. Vowel reduction: the initial pretonic position

Virtually all major works on the phonology of English recognize that ‘Latinate’ prefixesFootnote 3 have a specific reduction behaviour (Chomsky & Halle Reference Chomsky and Halle1968: 118; Halle & Keyser Reference Halle and Keyser1971: 37; Liberman & Prince Reference Liberman and Prince1977: 284–285; Guierre Reference Guierre1979: 253; Selkirk Reference Selkirk1980, Hayes Reference Hayes1982; Halle & Vergnaud Reference Halle and Vergnaud1987: 239; Pater Reference Pater2000, Hammond 200ny of the other3; Collie Reference Collie2007: 129, 215, 318–319). Initial pretonic closed syllables normally do not contain reduced vowels (1a) whereas prefixes in that position almost always do (1b).

In other environments, such prefixes may have unreduced vowels (e.g. [á]dverb, c[ɒ́]ncert, s[ʌ́]bscript), and we also find alternations between reduced (2a) and full vowels (2b) between morphologically related words.

To our knowledge, the only proposed explanation for this particular behaviour is given by Hammond (Reference Hammond2003). Building on previous work by Fidelholtz (Reference Fidelholtz1975), he argues that, since high-frequency items tend to reduce more than low-frequency items and because these prefixes are quite frequent, it is hardly surprising that these prefixes should be reduced. This is the only proposal that we are aware of in which the frequency of an affix (as opposed to that of a whole word) is assumed to be relevant, and it is still a hypothesis that has not been tested empirically. Formally, Hammond analyses the difference between high- and low-frequency items by assuming that they are indexed to different constraints (Pater Reference Pater2000, Reference Pater2009a). The effect of lexical frequency is usually interpreted in information–theoretic terms: more frequent items are more predictable and less informative, and so it is expected that they undergo more phonetic reduction, while less frequent and less predictable items are expected to undergo less reduction.Footnote 4

Raffelsiefen (Reference Raffelsiefen2007) proposes an alternative analysis. She claims that vowel reduction in closed initial syllables is specific to verbs. However, she contrasts only prefixed verbs (e.g. contain, obsess, suspect) and non-prefixed nouns (e.g. canteen, pontoon, sestet). There are only two disyllabic non-prefixed verbs with final primary stress and a closed initial syllable, bl[a]sphéme and sh[a]mpóo, but both have full vowels in their first syllable. However, they may be unreliable because of the existence of a related noun (shampoo) or a morphologically related word with stress on that syllable (blásphemy). Likewise, prefixed nouns with final stress are scarce, but all have reduced vowels (e.g. c[ə]nstráint, c[ə]ntémpt, s[ə]spénse). Again, that behaviour can be attributed to the corresponding verbs (constrain, contempt, suspend). Therefore, one needs to go beyond those data to establish what the presence of reduced vowels should be attributed to. The following study that we discuss partly provides us with evidence that prefixation is indeed the key criterion.

Dabouis & Fournier (Reference Dabouis and Fourniersubmitted), in a large-scale multifactorial study of vowel reduction in British English using dictionary data, report a significant difference between words containing a monosyllabic prefix (defined based on etymology – words with compositional semantics are excluded for that part of the study) and words which do not. Prefixation is tested in several regression analyses including multiple covariates (e.g. word frequency, syllable structure, spelling), and comes out as a highly significant predictor of vowel reduction, independently of those covariates. Figure 1 reproduces their results for words which are not derived from a free base and whose initial pretonic syllable does not contain an orthographic digraph, which they found to impact vowel reduction.

Figure 1. Vowel reduction in the initial pretonic syllable of non-derived words (figures from Dabouis & Fournier Reference Dabouis and Fourniersubmitted).

As can be seen in Figure 1, non-prefixed words have reduced vowels in 66% of cases in which the syllable is open and 8% of cases in which it is closed, while prefixed words have 96% and 80% of reduced vowels in these environments, respectively. The difference persists in stress-shifted derivatives (e.g. contéxtual ← cóntext; solídity ← sólid), in open syllables (48% vs. 80%) and closed syllables (9% vs. 73%).Footnote 5 That last point clearly contradicts Raffelsiefen’s (Reference Raffelsiefen2007) claim above that the presence of reduced vowels is attributable to syntactic categories. She discusses disyllables exclusively, and we saw that it is virtually impossible to tease apart the effects of prefixation from those of syntactic categories in disyllables. The longer stress-shifted derivatives studied by Dabouis & Fournier, which are mainly nouns and adjectives, have reduced vowels significantly more often when they are prefixed than when they are not, which shows that those prefixes reduce regardless of syntactic categories.

To sum up, in this section, we saw that words which have semantically opaque prefixes in their initial pretonic position have reduced vowels significantly more often than non-prefixed words.

2.1.2. Vowel reduction: the second syllable of disyllabic words with initial primary stress

Using dictionary data, Guierre (Reference Guierre1979: §4.2.6) observed that the presence of a reduced vowel in the second syllable of disyllabic non-prefixed words with initial primary stress appears to be the rule (87% of words; e.g. álb[ə]rt, báll[ə]st, hárv[ɪ]st, hón[i], sérp[ə]nt, pílf[ə]r), while opaque prefixed words (which he calls ‘inseparable’) follow the opposite tendency (84% of words have unreduced vowel; e.g. ádv[ɜː]rt, cómm[ɛ]nt, cóntr[ɑː]st, díg[ɛ]st, súrv[eɪ], tránsf[ɜː]r). However, this may be due to the fact that disyllabic nouns with trochaic stress which are related to a verb with final stress (e.g. escort, import, project) tend to have full vowels in their second syllable (Fudge Reference Fudge1984: 32, 167; Poldauf Reference Poldauf1984: 38). Although the majority of words concerned by this generalization are prefixed, it occasionally extends to non-prefixed words (e.g. férm[ɛ]nt (n), tórm[ɛ]nt (n)). The only study to have sought to untangle both possible generalizations is Dahak (Reference Dahak2011), which reports a study based on data from pronunciation dictionaries on 9500 disyllabic words with initial stress, 5.5% of which are prefixed. The overall figures that she reports are similar to those found by Guierre (Reference Guierre1979), but she provides more detail on this issue: in her dataset, a quarter of words have a related form with final stress (e.g. abstract, perfect, protest) and 96.3% of those words are attested with a full vowel in their second syllable. In contrast, the remaining three quarters which do not have a related form with final stress (e.g. abject, expert, transept) may have a full vowel in 81.5% of cases. Therefore, even if we isolate the effects of the existence of a related word with primary stress on the second syllable, opaque prefixed words still have a behaviour that is the exact opposite of non-prefixed words. Although Dahak does not always provide word counts and does not conduct a multifactorial analysis, the magnitude of the difference between prefixed and non-prefixed words suggests that this difference would persist in a more controlled study.Footnote 6

In this section, we saw that disyllabic opaque prefixed words with initial primary stress often have full vowels in their second syllable, unlike non-prefixed words which nearly never have full vowels in that position. In the case of nouns, we saw that this cannot systematically be attributed to the fact that such nouns are related to a verb with final primary stress (although it can further increase the chances of having a full vowel).

2.1.3. Primary stress

In a large dictionary study on primary stress placement in verbs, Dabouis & Fournier (Reference Dabouis, Fournier, Ballier, Fournier, Przewozny and Yamada2023) test two generalizations proposed in the literature regarding the parameters that determine the position of primary stress: the syllabic weight of the final syllable and the morphological structure of verbs. The ‘weight-based generalization’, which is inherited from Chomsky & Halle (Reference Chomsky and Halle1968) and has been preserved in most of the subsequent literature in various forms (see e.g. Hayes Reference Hayes1982; Burzio Reference Burzio1994: 43; Hammond Reference Hammond and Durand1999: 263), predicts that stress should be final if the final syllable is heavy, and penultimate otherwise. This follows from the assumption that stress is quantity–sensitive and rightmost in English and that the final consonant of verbs does not contribute weight. One noticeable exception to this is that trisyllabic verbs that have a heavy final syllable usually have antepenultimate stress, except if their final syllable is a root (Chomsky & Halle Reference Chomsky and Halle1968, Liberman & Prince Reference Liberman and Prince1977, Hayes Reference Hayes1982). The ‘morphology-based generalization’ predicts that stress should fall on the root in opaque prefixed verbs. These parameters are evaluated on a subset of their data which contains both morphologically simple words and words containing bound roots, where the presence of affixes is determined using etymology. They find that both weight and prefixation are highly significant predictors of the position of primary stress in a binary logistic regression. Their results show that both parameters make identical predictions in the majority of cases, many of which are either prefixed with a heavy final syllable or non-prefixed with a light final syllable. The figures that they report for disyllabic words are reproduced in Figure 2. Remember that those do not include opaque prefixed words in which the base is free (e.g. become, express, reclaim), in which primary stress is base–initial in 99% of cases, and so the word treated as ‘prefixed’ in Figure 2 all have bound roots.

Figure 2. Position of primary stress in disyllabic verbs depending on the weight of the final syllable (H = heavy and L = light) and on the presence or absence of an opaque prefix (from Dabouis & Fournier Reference Dabouis, Fournier, Ballier, Fournier, Przewozny and Yamada2023).

Overall, the two parameters have comparable efficiencies, but both fail to capture part of the data. The weight-based generalization fails to capture prefixed words with a light final syllable and final stress (e.g. attack, commit, repel) whereas the morphology-based generalization fails to capture non-prefixed words with a heavy final syllable and with final stress (e.g. lament, molest, usurp). In longer verbs, the same observation holds, as primary stress is base–initial in 115/138 (83%) of cases (e.g. àpprehénd, còntradíct, demólish, èntertáin, ìntermít, remémber, rètrogréss, surrénder). Crucially, trisyllabic verbs with two prefix syllables and a heavy final mostly have final stress, and this differs from non-prefixed verbs (e.g. dámascene, gállivant, mánifest). If the final is light, penultimate stress is more systematic for verbs with a monosyllabic prefix than in non-prefixed verbs (e.g. sequéster vs. mónitor). These results show that both generalizations constitute viable analyses of stress placement in verbs.

Moreover, they report that, in American English, there is a significant difference between words in <-ate> which contain a prefix (e.g. ablate, debate, relate) and those which do not (e.g. castrate, dictate, rotate), as ‘the former have final stress as their main pronunciation in 13/14 words, while the latter have final stress in 9/35 words’ (chi-squared=15.609, df = 1, p < .001), as observed previously by Halle & Keyser (Reference Halle and Keyser1971: 68–69) and Guierre (197: §1.2.2).

Guierre (Reference Guierre1979) reports similar figures for verbs but also gives the figures shown in Figure 3 for disyllabic adjectives and adverbs.

Figure 3. Position of primary stress in disyllabic adjectives and adverbs depending on the presence or absence of an opaque prefix (figures from Guierre (Reference Guierre1979))

There too, there is a highly significant difference between prefixed and non-prefixed words, both for adjectives (chi-squared = 786.02, df = 1, p < .001) and adverbs (chi-squred = 194.53, df = 1, p < .001). In longer words, Guierre (Reference Guierre1979) reports that non-suffixed adjectives have antepenultimate stress if the final syllable is heavy, and that no difference is observed between prefixed (e.g. ábsolute, dérelict, óbsolete, résolute) and non-prefixed words (e.g. ádamant, fúribund, máritime, móribund) but notes that those classes are very restricted (15 words in total). In non-suffixed adjectives that end in a light syllable (/-VC/), prefixed words have penultimate stress (e.g. intrépid, insípid, implícit, explícit, decrépit) while non-prefixed words have antepenultimate stress (e.g. fínikin, fílemot, áliquot, Sáracen, mínikin, sínister) but again the relevant classes are very small (the 11 examples that we gave are the complete list).Footnote 7

The results reported by Guierre (Reference Guierre1979: §4.2.5.5 and §4.2.6) also show a significant difference in how primary stress is assigned to disyllabic nouns (chi-squared = 63.119, df= 1, p < .001), though not as strong as that found in verbs, adjectives and adverbs, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Position of primary stress in disyllabic nouns depending on the presence or absence of an opaque prefix (figures from Guierre (Reference Guierre1979)).

As can be seen in Figure 3, he finds that disyllabic nouns have initial stress more often when they are not prefixed (4,099/4,416 – 93%; e.g. beauty, radish, visa) than when they contain an opaque prefix (347/425 – 81%; e.g. absence, congress, digest). If one considers the figures that he reports regarding how many words are prefixed (among the words that do not contain any productive morphology or stress-affecting endings), we can see that verbs are, in their vast majority, prefixed (1,032/1,345 – 77%), but the same is not true of nouns (425/4,841 – 9%).

For longer nouns, Guierre reports no difference between non-prefixed and prefixed words (e.g. cómpany, déficit, éxodus, précipice), but he does not provide figures or statistical tests to base his observation. Therefore, further research is needed to replicate and consolidate that finding. However, the results on disyllables are robust: there is a difference between prefixed and non-prefixed nouns, although the difference is considerably smaller than that observed in verbs, adjectives and adverbs, which are almost systematically stressed on their base. This often results in stress patterns that are distinct from those of non-prefixed words.

2.1.4. The diachronic evolution of stress in verb–noun pairs

Sonderegger & Niyogi (Reference Sonderegger, Niyogi and Yu2013) report a study of the diachronic evolution of disyllabic verb–noun pairs such as convict, concrete or exile. They find that most observed changes lead to diatonic pairs in which the verb has final stress and the noun has initial stress, although most pairs do not change if they are in what they call a ‘stable state’ (both are stressed on the first syllable, both are stressed on the second syllable, or the verb has final stress, and the noun has initial stress). They find that the words which share a prefix tend to evolve in a similar direction, and they note that that is ‘particularly interesting because it suggests that it is a shared morphological prefix rather than simply shared initial segments which correlates with trajectory similarity’. Therefore, one might interpret the fact that words that share a prefix evolve in a similar direction as an indication that those prefixes are detected by language users of English.

2.1.5. Secondary stress

Robust effects of opaque prefixation were reported by Arndt-Lappe & Dabouis (Reference Arndt-Lappe and Dabouissubmitted) in suffixal derivatives. The study sought, among other things, to replicate Collie’s (Reference Collie2007) finding that weak preservation may fail and that this failure can be attributed to the relative frequency of the base and its derivative. Weak preservation designates the preservation of the primary stress of a base as a secondary stress in its derivative (e.g. oríginal → orìginálity). The earlier literature assumed that this phenomenon was categorical (Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky1979, Hammond Reference Hammond1989, Halle & Kenstowicz Reference Halle and Kenstowicz1991) but Collie found that there were instances of (possible) preservation failure (e.g. authórity → authòritárian ~ àuthoritárian). Arndt-Lappe & Dabouis report two studies, one based on dictionary data and one based on oral data. While evidence of relative frequency was only found for the oral data, both studies report that opaque monosyllabic prefixes favour second-syllable stress preservation.Footnote 8

Therefore, there is some evidence of the stress-repellent effect of opaque prefixes with regards to pretonic secondary stress placement.

2.1.6. Phonotactics

Guierre (Reference Guierre1990) proposed that certain consonant clusters which are illicit in simplex words can indicate the presence of a morphological boundary. He notes that the only clusters of two obstruents which are attested word-medially in simplex words are voiceless clusters. Hammond (Reference Hammond and Durand1999: §3.3) has conducted a more extensive survey of distributional regularities in English and found slightly different results but also identifies medial clusters which can be found only (or mostly) in constructions with Latinate prefixes, such as:

-

• those with voicing disagreements involving voiceless fricatives: [bs] abcess, absence, subsidy, [bf] obfuscate; Footnote 9

-

• certain clusters containing a voiced stop followed by a sonorant: [bm] submerse, [dm] admire, [bn] obnoxious;

-

• most clusters containing a voiced stop followed by a voiced fricative or affricate: [bv] obvious, [bz] absolve, [dv] advantage, [bdʒ] object, [gdʒ] suggest;

-

• [dh] in adhere, a cluster normally only created by concatenation, e.g. childhood, madhouse.

Therefore, it can be argued that these clusters function as ‘boundary signals’ and can favour the recognition of a structure in these words. It is also possible that there are other phonotactic elements which may make words more or less likely to be interpreted as prefixed. For example, many roots end in VVC or VCC, with consonant clusters that are very typical of such roots (e.g. [pt, kt]).

Therefore, although more investigation is needed regarding which phonotactic cues might affect how likely it is for a word to be interpreted as prefixed, some word-internal clusters that do not occur in simplex words are found in opaque prefixed words and are therefore available to listeners as boundary signals marking the prefix–root boundary.

2.2. Morphological evidence: selectional restrictions and allomorphy

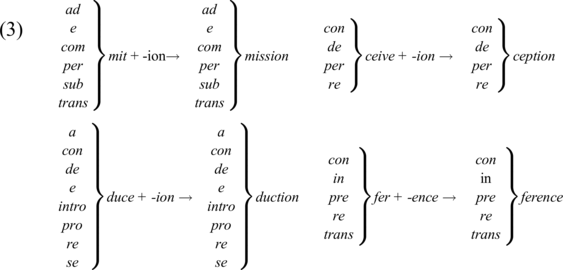

Aronoff (Reference Aronoff1976: 12–15) suggests that units such as fer or mit are ‘somehow relevant to the morphology’ because the verbs sharing a bound root have the same standard nominalizing suffix, sometimes accompanied by root allomorphy, as shown in (3).

Aronoff argues that prefix–root words in mit all contain the same root and not different homophones. He also observes a similar phenomenon for verbs which share the same irregular inflection even in the absence of semantic similarity (Aronoff Reference Aronoff1976: 14), as can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Irregular inflection in prefixed and non-prefixed words sharing a root

However, Plag (Reference Plag2003: 26–27) rejects the argument that this is evidence for semantically-impoverished morphemes on the grounds that these facts ‘can equally well be described in purely phonetic terms’. To claim that the morphology needs to refer to the roots in these words, one would need cases in which the end of the verb would contain a phonetic string that is identical to a given root and that this string should not actually be a root. Some have proposed such examples as vomit → *vomission, but Plag rejects that example on the grounds that it is not in fact phonetically identical to the verbs with the root mit because it is stressed in these verbs but not in vomit. This leads Plag to conclude that units such as mit or fer should not be treated as morphemes and that ‘there is no compelling evidence so far that forces us to redefine the morpheme as a morphological unit that can be without meaning’.

What Plag does not mention is the difficulty of finding relevant examples to test that claim. There are hardly any verbs which are non-prefixed and have final stress (in an exhaustive dictionary study, Dabouis & Fournier (Reference Dabouis, Fournier, Ballier, Fournier, Przewozny and Yamada2023) find only 31 such verbs). Therefore, the argument suffers from a lack of support of compelling evidence and the alternative of a phonetically-driven affix selection process seems ad hoc. Although affixes have been shown to be selected based on the morphological structure of the base or the stress pattern of the base (e.g. Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky, Van der Hulst and Smith1982, Raffelsiefen Reference Raffelsiefen2004, Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013), they have not, as far as we know, been shown to be sensitive to such complex structures as a whole syllable along with its prosodic specifications (e.g. [-ˈmɪt] or [-ˈfɜː]). Before concluding that there is ‘no compelling evidence’, one would have to review more than a single process, as we have done in the previous sections.

Following Aronoff’s claim, it could be assumed the alternations in (3) can function as cues that roots are morphological units and that the words that contain them should be analysed as complex. However, in a segment-shifting study, Melinger (Reference Melinger2001) reports results suggesting that the complexity of words containing alternating roots is more difficult to access than that of those containing non-alternating roots. The study consisted in presenting participants with a source word (e.g. cooperate, coconut) in which (pseudo)affixes are highlighted simultaneously with the presentation of the target word (e.g. author), to which they are asked to attach the highlighted section of the source word and pronounce a response word (e.g. co-author). The experiment contained words with free stems (e.g. defrost), bound roots (e.g. deceive; some of which had several forms) and simple words (e.g. denial) and it was expected that it would be easier to shift the highlighted section if the source word is morphologically complex. She finds that this is indeed the case, although the results regarding items with bound roots are unclear as they are not significantly different from simple words and items containing free stems, but simple words are significantly different from items with free stems. Moreover, alternating roots were found to make the task more difficult, which she interprets as a sign that alternating roots ‘have weaker relationships to their morphological family members’ than non-alternating roots. However, her study suffers from limitations, such as the small number of words used and the heterogeneity of the alternations considered (she included words with common alternations such as depar[t] → depar[tʃ]ure alongside cases like revolve → revolution), and her results have not been replicated.

Therefore, we have seen that certain roots have a stable allomorphic behaviour in the different words that contain them, and some roots tend to associate with specific nominalizing suffixes. The results reported by Melinger suggest that it is possible that root allomorphy actually impedes the identification of morphological structure more than it facilitates it, but more evidence is required to confirm her observations.

2.3. Psycholinguistic evidence

2.3.1. Lexical decision

Several psycholinguistic studies have shown that prefixed words with bound bases (generally referred to as ‘bound stems’ in that literature) and which have obscure semantics are processed differently from words without any morphological structure in lexical access, and are often processed similarly to complex words with free bases (referred to as words with ‘free stems’). Taft & Forster (Reference Taft and Forster1975) (Experiment III; later replicated with more thoroughly controlled materials in Taft (Reference Taft1994)) found that, in a lexical decision task, participants took longer to reject prefixed non-words which contained a bound stem (e.g. devade, with vade from evade, invade) than those which did not (e.g. depoch, with poch from epoch). Taft et al. (Reference Taft, Hambly and Kinoshita1986) also found that non-words with non-prefix initial elements (e.g. tejoice, asiwhelm, lanlediate, asiwhast), even if they contained bound stems, were rejected faster than those with initial prefixes (e.g. dejoice, uniwhelm, dejouse, conlediate). This suggests that stems are isolated via what the authors call a ‘prefix-stripping procedure’. A recent study, Coch et al. (Reference Coch, Hua and Landers-Nelson2020), which compared word and non-word stimuli with bound stems (e.g. discern, predict, disject, percern) or with free morphemes (e.g. cobweb, earring, cobline, bobweb) with control monomorphemic stimuli (e.g. garlic, minnow, gartus, buzlic), found that stimuli with bound stems were processed differently in words and non-words. Indeed, they report no significant differences in accuracy and response times between bound stem and control monomorphemic words, but they find that bound stem and free morpheme non-words have comparable accuracies and response times, with lower accuracy and longer response times than monomorphemic non-words. They suggest that there is a ‘cost’ to the identification of morphological structure, even in the absence of semantics (in non-words), hence lower accuracies and longer response times.

To neutralize the effects of semantics, other researchers have conducted lexical decision tasks with maskedFootnote 10 priming with prefixed words containing bound stems (e.g. explore) or free stems (e.g. distrust) and found the same amount of priming facilitation for both structures, while controlling for orthographic factors (Forster & Azuma Reference Forster and Azuma2000, Pastizzo & Feldman Reference Pastizzo and Feldman2004). Pastizzo & Feldman (Reference Pastizzo and Feldman2004) interpret this result as evidence that words composed of bound and free stems have similar representations.

Moreover, lexical decision latencies may be influenced by several factors such as the semantic transparency of the stem (as suggested by Taft & Kougious (Reference Taft and Kougious2004); e.g. venge as in revenge, avenge, vengeful, vengeance has a clearer meaning than ceive in receive, deceive, conceive, perceive), the number of morphological relatives containing the same stem (Forster & Azuma Reference Forster and Azuma2000; Pastizzo & Feldman Reference Pastizzo and Feldman2004; e.g. the stem mit can be found in more words than the stem vive) or the cumulated frequency of the stem in all the words in which it appears (Taft Reference Taft1979; e.g. proach in approach and reproach has a higher frequency than suade in persuade and dissuade; lexical decision latencies are reported to be faster for reproach than for dissuade even though these words have equivalent printed frequencies).

In a review of the issue, Rastle & Davis (Reference Rastle and Davis2008) discuss evidence from 19 studies on visual word processing and conclude that ‘morphological decomposition is a process that is applied to all morphologically structured stimuli, irrespective of their lexical, semantic or syntactic characteristics’. This morpho–orthographic decomposition would appear to take place in the early stages of the recognition process, independently of semantics (see Marslen-Wilson et al. (Reference Marslen-Wilson, Bozic and Randall2008) and references therein). Although some studies do find a difference between transparent and opaque items, most of them assume that there is such a thing as morpho–orthographic decomposition which can apply to opaque items (e.g. Diependaele et al. Reference Diependaele, Sandra and Grainger2009, Feldman et al. Reference Feldman, O’Connor and Del Prado Martín2009; see Heyer & Kornishova Reference Heyer and Kornishova2018 for an overview). In a recent review of the issue, Beyersmann & Grainger (Reference Beyersmann, Grainger and Crepaldi2023) draw similar conclusions, and they point out that semantically-blind decomposition is acquired late and that ‘morphological processing is primarily guided by semantics during the initial stages of reading acquisition’.

While most of the evidence comes from visual word processing, hence the term ‘morpho–orthographic’ used here (and in the literature), the little available evidence on spoken-word processing also suggests that morphological information is processed irrespective of semantic transparency in the first moments of processing (see Creemers (Reference Creemers and Crepaldi2023) for a review of spoken-word morphological processing and Emmorey (Reference Emmorey1989) for evidence on the auditory processing of prefixed words).

2.3.2. Reading studies

Four studies have shown a significant impact of prefixes on stress placement in reading tasks. Previous work had shown that words with segmental exceptions were read more slowly than regular words. For example, orthographic vowels followed by two consonants are usually pronounced as short vowels (e.g. mint [ˈmɪnt]), and so words which do not follow this generalization (e.g. pint [ˈpaɪnt]) tend to be read slower. Rastle & Coltheart’s (Reference Rastle and Coltheart2000) aim was to see whether this would be true of stress exceptions as well: are exceptions to stress rules read slower than words that obey them? In a first reading experiment, where they classified disyllabic English words as ‘regular’ if they had initial stress and ‘irregular’ if they had final stress, no effect of stress regularity was found. The authors then redefined their model of stress regularity. Following Fudge (Reference Fudge1984), they classified as ‘regular’ words with final stress which either contained a prefix (e.g. ad-, de- sub-) or a stress-taking suffix (e.g. -ette, -oon, -ade). In a second experiment, they asked participants to read 210 non-words, which could have either final stress (if they were prefixed or contained a stress-taking suffix) or initial stress (otherwise). They compared the participants’ productions to those of an algorithm programmed to predict stress based on the morphology of words and found a very high similarity between them. This led them to conclude that:

there seem to be a class of item that reliably takes second syllable stress. We suggest that this pattern of stress assignment may be related to the presence of morpheme-like orthographic segments—prefixes and stress-taking suffixes—which serve to place stress.

(Rastle & Coltheart Reference Rastle and Coltheart2000: 352)

Finally, they reproduced the first experiment with this new definition of regularity using 60 target words. They found significant effects of word frequency (there were longer naming latencies and higher error rates for low-frequency items) and stress irregular items (there were longer naming latencies and higher error rates for irregular items). They also found that 90% of errors were pure stress regularizations. Let us note that not all the possible determiners were taken into consideration in that study and that this could bias the results that they report.

The second study is that of Ktori et al. (Reference Ktori, Tree, Mousikou, Coltheart and Rastle2016), which focused on the reading of disyllabic prefixed words, which were treated as regular if they had final stress and irregular if they had initial stress, by patients with acquired surface dyslexia, which they define as ‘an acquired disorder of reading in which the reading aloud of irregular words is impaired while the reading aloud of nonwords is spared’. Following Rastle & Coltheart (Reference Rastle and Coltheart2000), they predicted that patients would regularize irregular prefixed words and assign them final stress. Five patients were asked to read 150 words, which fell into one of three categories: regular prefixed (e.g. remind), irregular prefixed (e.g. reflex) and non-prefixed with initial stress (e.g. climate). The results showed that patients were more likely to pronounce irregular prefixed words with final stress than non-prefixed words, therefore confirming the authors’ hypothesis that ‘prefixes repel stress’. As for the previous study, not all possible predictors of stress are controlled for (e.g. syntactic categories).

Ktori et al. (Reference Ktori, Mousikou and Rastle2018) investigate a larger range of potential determiners of stress placement in reading disyllables, some of which were not taken into consideration by previous studies. They conduct factorial experiments in which participants have to read non-words to disentangle potential cues to stress placement. These cues can be ‘sublexical’ (vowel length, orthographic weight, prefixation) or ‘sentence-level’ cues (grammatical category, rhythmic context). They report an effect of prefixation that is independent of other cues, which were all found to have an impact on stress placement in non-words.

The last study, Treiman et al. (Reference Treiman, Rosales, Cusner and Kessler2020), investigates several factors which have been claimed to influence how stress is placed in disyllabic English words and non-words, using experimental data (Studies 1–4) and dictionary data (Study 5). They report significant effects of the number of initial consonants, the number of final consonants, the syntactic context (nominal or verbal) and the presence of a prefix-like sequence (based on the classification used in Rastle & Coltheart (Reference Rastle and Coltheart2000)), both for production data (sentence reading tasks) and in a relevant subset of the Unisyn lexicon (3,071 words).Footnote 11 Their results show that, in both cases, stress is highly predictable, although no factor has a ‘none-or-all’ effect, as could be expected by Rastle & Coltheart’s (Reference Rastle and Coltheart2000) model. The presence of a prefix is a factor which, among others, is probabilistically associated with a position of stress (second syllable), as shown by the mixed-models analyses that they report.

To sum up, those four studies all find prefixation to be a significant predictor of the position of stress in the reading of disyllabic words, although readers do not seem to apply a categorical rule not to assign stress to prefixes. The last two studies are the only ones to include syntactic categories among the covariates. This seems to be necessary given the important differences found between nouns and other syntactic categories that we reviewed in §2.1.3.

2.3.3. ERP

McKinnon et al. (Reference McKinnon, Allen and Osterhout2003) conducted an ERP study using 60 words containing bound stems (e.g. submit, receive), 60 non-words with the same prefixes and roots (promit, exceive), 60 control morphologically complex words (e.g. bookmark, muffler) and 60 control non-words with no apparent morphemes (e.g. moobkark, flermuf).Footnote 12 Participants saw the (non-)words on a screen and had to say whether or not they were English words. The N400 component of the ERP is known to be sensitive to lexical status (word vs. non-word) and frequency of the letter string: there is a higher amplitude for non-words and less frequent words than for words and specifically for more frequent words. They summarize the logic of their experiment as follows:

If readers treat the (experimental non-words (e.g. promit, exceive)) as unanalyzed wholes, then the non-words should elicit larger amplitude N400s than the real words. This follows from the fact that whereas the words are relatively frequent in English, the bound-stem non-words (taken as a whole unit) are non-words with zero frequency. Conversely, if readers decompose the words and non-words into their constituent morphemes, and if these morphemes are represented in the mental lexicon, then the words and non-words might elicit similar amplitude N400s; both the words and non-words are made up of morphemes with the same frequency.

(McKinnon et al. Reference McKinnon, Allen and Osterhout2003: 883)Their results show that only the control non-words elicited a larger N400 amplitude than the words. They interpret these results as being ‘consistent with a model in which a morphologically complex letter string is parsed into its morpheme components, even when these morphemes are non-productive and semantically impoverished’.

A similar study, Coch et al. (Reference Coch, Bares and Landers2013), using a more controlled methodology and more participants (16, while McKinnon et al. (Reference McKinnon, Allen and Osterhout2003) had 12), found differences in N400 responses between items with free morphemes and those with bound morphemes. They interpret these results by saying that the N400 may actually correspond to a process of recomposition guided by semantics, and that semantically-blind decomposition takes place earlier. They also report behavioural results (accuracy and reaction times) that are consistent with the literature reported in §2.3.1: items with bound or free morphemes differ from control items but not necessarily from each other.

Therefore, those two studies report inconsistent results regarding the N400 component of the ERP as to its sensitivity to meaning, so further replications of those studies would be welcome.

2.4. Semantic relics

In the previous sections, most of the work that we have cited treated words such as conceive, emit or subtract as semantically opaque, in the sense that their internal constituents have no clear identifiable meaning (although some use the term ‘semantically impoverished’). As we have seen, this is a central element for rejecting morphemic status to the constituents of those words, at least for those assuming that morphemes are defined at least partly by their meaning.

However, there have been proposals arguing that certain roots have some meaning that is shared by all the words that contain them. Fournier (Reference Fournier1996) argues that this can be seen quite clearly with cases such as those in (4), in which the root spect is systematically associated with an idea of sight and the root rupt with an idea of breaking.

This observation can be extended to prefixes, which sometimes contribute meaning, even though the meaning of the whole word is far from compositional. This can be seen in cases such as (5a), in which productive prefixes are attached to bound roots, or in (5b–c), in which the prefixes re- and ex- have a recurrent meaning, ‘back’ and ‘out,’ respectively, but that meaning is not the one found in the productive prefixes re- and ex-, ‘again’ and ‘former’. Thus, those are probably best analysed as homographic prefixes, some of which may only attach to bound bases.

A similar argument is developed by Baeskow (Reference Baeskow2006) within the framework of the feature-based theory of word formation (Baeskow Reference Baeskow2002, Reference Baeskow2004). Following Dowty (Reference Dowty1991), Baeskow assumes that thematic roles are best seen as ‘cluster concepts rather than discrete categories’. Traditional thematic roles (e.g. patient, agent, instrument) are replaced by two proto-roles, which are defined over ‘lexical entailments’ (e.g. sentience, change of state, movement). Some of these entailments are associated with the ‘proto-agent’ and some with the ‘proto-patient’, and the number of entailments of each proto-role determines whether an argument is realized as a subject or a direct object. Baeskow claims that,

even from a synchronic point of view, each bound verbal root of Latin origin which is recurrent makes at least a small contribution to the semantic interpretation of the sets of verbs it heads in that it entails fragmental – or, borrowing Lieber’s (Reference Lieber2004) terminology – skeletal thematic information.

(Baeskow Reference Baeskow2006: 19–20)She defends this claim by focusing on six roots, duce, scribe, ceive, sume, mit and port, and she shows that they have such skeletal thematic features. We reproduce in (6) the argument structure that she claims is associated with those six roots, in which <E> refers to a referential argument and the subscripts refer to the entailments associated with the two proto-roles.

Baeskow claims that those roots have lexical entries which contain their argument structure and that the lexical entries of prefixed verbs ‘only add those properties which are not predictable from the entry of the root’. She also claims that the same type of ‘skeleton’ could be found for all recurrent Romance roots (although this is not demonstrated) and that her analysis predicts that those roots may be used to coin new words and provides support for her claim by citing examples from online sources (e.g. subceive, exduce, rescribe).

Let us note that Baeskow funds her analysis on occurrences in natural speech taken from online corpora, but that the analysis is qualitative. No quantification or statistical analysis is provided, and we are not told whether those entailments are different from what is found in non-prefixed verbs (e.g. is the feature [affected] absent in many dynamic verbs?). Therefore, the extension of her analysis to more roots and with quantitative aspects remains to be conducted.

In this section, we have seen that, at least for some prefixes and roots, there are semantic features that are shared by several or all the words that contain them, that they are not all opaque to the same degree, and those shared semantic features may participate in the identification of those constituents.

2.5. Interim summary

Let us sum up the main results that we have reviewed so far. We saw that opaque prefixed words differ from non-prefixed words in that:

-

• They near–systematically have reduced vowels in initial pretonic syllables;

-

• They quite generally have full vowels in the second syllable of disyllabic nouns with initial primary stress;

-

• They have primary stress on their root in verbs, adjectives and adverbs, which generates patterns which diverge from non-prefixed words;

-

• They have higher rates of final primary stress in nouns;

-

• They have undergone similar changes regarding the position of stress in verb–noun pairs if they share a prefix;

-

• They favour second syllable stress preservation in stress-shifting derivatives;

-

• They display specific phonotactic patterns, especially word-internal consonant clusters.

We also saw that reference to morphological complexity may be necessary to account for certain allomorphic behaviours and affix selectional restrictions. We saw that there is evidence from most psycholinguistic studies that we are aware of that prefixed words with ‘bound stems’ and opaque semantics are treated like complex words by participants, the only exceptions being experimental designs which do not neutralize semantic effects. Given the semantic opacity of such words, that result is actually to be expected. Finally, we saw that the prefixes and roots found in such words are not all entirely opaque and that roots such as duce or mit may be argued to share ‘skeletal’ thematic features.

Therefore, the evidence appears sufficient to reject the idea that opaque prefixed words are to be treated as simplex words. Any model seeking to maintain that idea would have to propose alternative accounts of the phonological processes and psycholinguistic results which we have reviewed. However, what we have seen so far raises several questions. First, one may wonder what the advantages of storing a word such as permit as per+mit could possibly be for the linguistic system. This question is discussed by Forster & Azuma (Reference Forster and Azuma2000), who propose two answers. The first is that morphological structure is necessary for syllabification, independently of semantic transparency, as argued by Levelt et al. (Reference Levelt, Roelofs and Meyer1999). Levelt et al. discuss several studies on Dutch in which semantically empty formatives appeared to be necessary for syllabification, and so they ‘suggest that morphemes may be planning units in producing complex words without making a semantic contribution’. The second is that ‘the language acquisition system looks for and uses structure wherever it can be found’. A second question concerns the redundancy in lexical storage necessary if opaque prefixed words are analysed as complex words: as their meaning cannot be derived from that of their constituents, both the constituents and whole-word combinations may have to be stored in the lexicon. McKinnon et al. (Reference McKinnon, Allen and Osterhout2003) actually discuss this issue of redundancy and argue that a redundant system with both root and word storage ‘has considerable empirical and theoretical support’.

Finally, some may object that semantically opaque morphological structures are not learnable. We argue that the facts that we have reviewed can be accounted for by the assumption that speakers learn that opaque prefixed words are morphologically complex. As it cannot be assumed that they have access to etymological information, there must be synchronic cues which they can use. The phonological and morphological evidence reviewed in §2.1 and §2.2 may certainly constitute part of those cues, but other cues may also be used. In the following section, we argue that a key component is the distributional recurrence of prefixes and roots, sometimes facilitated by formal and/or semantic similarity with productive affixes or free stems.

3. Learning to Detect Complexity in Opaque Prefixed Words

The literature on the acquisition of derivational morphology shows that children first acquire morphological processes which involve little or no change in form or meaning between base and derivative (Tyler & Nagy Reference Tyler and Nagy1989, Clark Reference Clark, Lieber and Štekauer2014, Fejzo et al. Reference Fejzo, Desrochers, Deacon, Berthiaume, Daigle and Desrochers2018). Frequency plays a role but it seems to be moderated by communicative usefulness (e.g. referential words are learned before function words, possibly because they are more useful to the child), more useful words being learned more quickly, even if they are not the most frequent, but frequency creates more opportunities for lexical learning (Ravid et al. Reference Ravid, Keuleers, Dressler, Pirelli, Plag and Dressler2020). Thus, children generally start by using conversion and very productive suffixes such as the diminutive -ie/y, adjectival -y or the agentive -er, in which there is an important overlap in form and meaning between bases and derivatives. Prefixes appear to be more complex and appear later, starting with un-. Suffixes that are associated with stress and vowel differences between the bases and their derivatives (e.g. -ion, -ity, -ic) are acquired after children enter elementary school. It appears that semantic transparency is crucial in the first steps of the acquisition of derivational morphology. Although we cannot diagnose the acquisition of the ability to detect morphologically opaque structures through the production of novel forms (as is done for productive morphology), it is quite likely that such words are identified as complex quite late. Elements pointing in that direction come from recent studies on morpho–orthographic segmentation, which show that the process of semantically blind automatic segmentation of all (apparently) morphologically structured stimuli in the early stages of visual word recognition emerges late (Rastle Reference Rastle2019, Marelli et al. Reference Marelli, Traficante, Burani, Pirelli, Plag and Dressler2020, Beyersmann & Grainger Reference Beyersmann, Grainger and Crepaldi2023), probably during adolescence (Dawson et al. Reference Dawson, Rastle and Ricketts2018).

Although morphologists may disagree regarding the way that morphological knowledge is represented, they usually assume that this knowledge is acquired through the comparison of sets of words. For example, Booij (Reference Booij, Hippisley and Stump2016) assumes that ‘language users can assign internal structure to a word if there is a systematic correlation between its form and meaning, based on the comparison of two sets of words’ and he then illustrates that mechanism using words that contain the agentive suffix -er and the corresponding verbs (e.g. dancer – dance; fighter – fight; singer – sing). As we have just mentioned, children can learn to identify bases that vary in form, and so we hypothesize that they can also learn to detect affixes that have little or no identifiable meaning, given sufficient distributional evidence. Taft (Reference Taft1994) assumes that a certain letter sequence does not need to be already identified as a prefix for a word to be analysed as having a prefix–root structure, this complexity ‘would simply emerge from the relationships that exist between words which share the same letter sequences’.Footnote 13 Forster & Azuma (Reference Forster and Azuma2000) and Taft (Reference Taft1994) also suggest that the commonality of forms like submit, admit, permit, prevent, advent, circumvent, etc. would be sufficient to create subunits like mit and vent. Wurm (Reference Wurm1997, Reference Wurm2000) also reports that ‘prefix likelihood’ (i.e. ‘the proportion of tokens beginning with a given letter string that are prefixed’, a measure introduced by Laudanna et al. (Reference Laudanna, Burani and Cermele1994)) and frequency could impact the processing of words. Finally, Fournier (Reference Fournier1996) assumes that the mechanism of ‘commutation’ (i.e. the mechanism inherited from European structuralism which allows for the identification of linguistic units when applied to minimal pairs, morphemes and phonemes, and is probably inherent to the speakers’ grammar) is the main cue which can be used by speakers to parse complex opaque structures.

Indeed, many prefixes and roots occur in several words, forming a network of prefix–root words, a sample of which can be seen in Table 2.Footnote 14

Table 2. An illustration of the network of prefixes and bound roots

If the similarities allowing complex structures to emerge can be purely based on form, then it is to be expected that such structures will also be identified in entirely non-productive prefixes such as se- (a prefix which comes from Classical Latin sē-, where it was already archaic; Gaffiot Reference Gaffiot1934: 1409), which is found with different roots (7).

Psycholinguistic evidence can also inform us of some of the ways that this network might impact the emergence of complex structures: as was seen in §2.3.1, the recurrence of the root and its cumulated frequency have been found to affect lexical decision latencies.

Some of the roots found in prefixed words can also be found in other types of morphologically complex words. This can likely contribute to the likelihood that words containing these roots will be identified as complex, even more so when there can be semantic similarities of the kind discussed in §2.4, as found in the examples in (8).

If semantic transparency helps in the detection of word-internal structure, then words such as aloud or surround are probably analysed as morphologically complex before words such as attain or submit. Likewise, in words with bound roots where prefixes contribute semantics that are the same as those found in words with transparent semantics, the identification of internal complexity is probably quite likely.Footnote 15 This is probably the case in isolated constructions (see (5a) and additional examples in (9)), in whole classes sharing semantics that may be associated with the prefix (see (5b)), and in series of words whose semantic opposition is based on that of their prefixes (10), such as the directional opposition in pairs in ex- and in-.

In those cases, the learner would operate comparisons between forms such as (9) and (10) and forms in which the same prefixes are attached to free bases and posit an internal structure that is similar to that of those words, except that the root is bound. Having analysed words such as (9) and (10) as internally complex could, in turn, facilitate the detection of complexity in words sharing the same roots, but with more opaque prefixes (11). For example, if one identifies decelerate as containing the negative prefix de-, then the bound base celerate will also be identified, and so accelerate will be more likely to be analysed as prefixed, even though its prefix is opaque. It is also possible that the meaning of the prefix of the second word in each of the pairs in (11), on account of the opposition with the other member, may be attributed semantic features that are the opposite of those of the prefix in the first member of the pair. For instance, decelerate contains the privative meaning usually found with the productive prefix de- (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Lieber and Plag2013: Ch. 17), and so the prefix ac- in accelerate may be associated with a ‘positive’ meaning, in opposition to de-.

This would be very similar to the analysis put forward by Taft (Reference Taft, Egbert and Sandra2003) regarding how language users may assign meaning to bound constituents such as hench, which is only found in henchman, i.e. in association with a free morpheme:

[A] henchman is a man and, therefore, hench might be taken to refer to “the thing that a man does in order to be a henchman”. In this way, it might be possible to work out what a henchwoman or henchdog means if those words were coined.

(Taft Reference Taft, Egbert and Sandra2003: 118)It is also possible that mere similarity of form facilitates the emergence of relevant units. One element in support of that view is that Dabouis (Reference Dabouis2024) reports that historically complex English proper names have phonological behaviours that resemble morphologically complex words more often when their first constituent resembles an existing word (e.g. Davidson, Holywell, Maryland), although there is no semantic connection to that word, than when it does not (e.g. Corydon, Hutcheson, Sheringham). This may manifest in prefixes and roots. In prefixes, the existence of homographic productive prefixes (e.g. de-, pre-, pro-, re-) may possibly favour complex interpretations.

Likewise, for roots, the existence of free forms possibly without any semantic relatedness (homophones and/or homographs; e.g. beget, perform, understand ) could facilitate the detection of morphological complexity. Further studies will have to establish whether there is a difference in how speakers treat words for which there is a relatively clear semantic connection with the free form (e.g. alight, oppress or adverbs like aloud, below) and those for which that connection is obscure or absent (e.g. inform, express).

If inconsistency in form impedes the identification of morphological constituents, as reported by the literature on the acquisition of derivational morphology cited above and Melinger’s (Reference Melinger2001) study (see §2.2), then the prefixes and roots that have several realizations (e.g. ad-/ab-/ac-/a-; con-/com-/cor-; ob-, o-, op-; tain/ten(tion); mit/mission; veal/vel(ation)) will probably be detected later than those which have a stable form (e.g. de-, pre-, pro-, port; vest). Moreover, among prefixes and roots that have different forms, all may not be equal, as alternations that occur relatively regularly in English, such as [t] ~ [ʃ] after -ion or -ial (e.g. protec[t] ~ protec[ʃ]ion) or vowel alternations caused by destressing (e.g. decl[ɛ́ː]re ~ dècl[ə]rátion) may complicate the identification of roots less than entirely unpredictable alternations (e.g. receive ~ reception). Therefore, we would assume that the detection of morphological structure in the various types of prefixed words that we have reviewed should proceed in an order that is after all quite trivial: units with the most constant overlap in form and meaning are detected first, and then the learner proceeds to detect more complex units displaying either variability in form and/or variable or unclear meaning.

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, we cannot exclude the possibility that different syntactic categories are treated differently, i.e. that opaque prefixation is detected more easily in certain categories than others.Footnote 16 If that is indeed the case, we would assume that the categories which contain the highest proportion of historically prefixed words are the ones for which prefixation will be detected first. If we use the figures given by Guierre (Reference Guierre1979) for disyllables shown in Figure 5, then verbs would be first (77% are prefixedFootnote 17), then adverbs (48%), then nouns (7%) and then adjectives (6%). Note that prefixed words with compositional semantics (which Guierre calls ‘separable’ prefixed words) are excluded from those counts.

Figure 5. Proportions of prefixed words among disyllabic verbs, adverbs, nouns and adjectives according to Guierre (Reference Guierre1979).

Finally, the phonological and morphological generalizations applying to opaque prefixed words, as we have suggested, resemble the sorts of semiproductive generalizations that are posited to occur at the stem-level in Stratal Phonology. As observed by Bermúdez-Otero (Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012):

[O]ne should countenance the possibility that variations in lexical experience across speakers may manifest themselves as differences in the extent to which individual learners acquire morphophonological generalizations over stem-level items, including whether or not they end up building parallel cophonologies: some speakers may acquire some aspects of stem-level phonology late, or not at all.

(Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012: 76; emphasis in the original)4. The structure of lexical entries

The evidence that we have reviewed can be taken to mean that most language users eventually parse all prefixed words into a prefix and a base, although this may not necessarily occur upon the first encounter with the word and that lexical entries may be reanalysed as a result of comparisons with other lexical entries. Obviously, the result of that parsing would be different depending on the semantic transparency of the prefixed word. If we adopt the framework of Stratal Phonology (Bermúdez-Otero 2018), words that have productive prefixes go through word-level phonology and may be stored analytically, or not at all (and so be produced only ‘on-line’).Footnote 18 If stored, the lexical entry of a word such as re-do would look something like (12).

This kind of representation is borrowed from Bermúdez-Otero (Reference Bermúdez-Otero2013) and Jackendoff (Reference Jackendoff1975). It uses two key ideas: morphologically complex words (or phrases) can be analytically listed in the lexicon (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012), i.e. in a decomposed form, and different levels of representation within a lexical entry can be coindexed (Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1997, Reference Jackendoff2002). In (12), we represent coindexation using postsubscripted Greek letters (α, β and γ). Here, all levels of representation are coindexed with one another. We voluntarily leave the semantic level relatively vague, as there are quite diverse ways to approach lexical semantics (see Acquaviva et al. (Reference Acquaviva, Lenci, Paradis, Raffaelli, Pirelli, Plag and Dressler2020) for an overview). Figure 126 is an arbitrarily chosen number representing the index of the entry.

The evidence reviewed in previous sections points to complexity at the morphological level despite the absence of complexity at the semantic level. Therefore, we propose that the lexical entries of opaque prefixed words are stored as in (13), with the example of the word submit.

Here, crucially, coindexation relates morphological constituents with their phonological realization (α and β), but the semantic representation is not related to those constituents and is directly related to the whole word on other levels (γ). Note that the structure present at the morphological level may be accessed by the morphology, e.g. to know which nominalizing suffix should be used for a given root. In Stratal Phonology, such an entry is typical of ‘nonanalytic listing’, i.e. ‘with their stem-level phonological properties fully specified’ (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012, after Jackendoff Reference Jackendoff1975). Such representations could explain why words like submit behave like words with productive morphology in psycholinguistic experiments that neutralize meaning but not when those experiments do not neutralize meaning (see §2.3.1). Note that nonanalytic listing does not imply that there cannot be internal complexity at the morphological or semantic levels, although an absence of complexity or compositionality may be a reason to store the word nonanalytically in the first place.

As we saw in §2.4 and in the previous section, a prefix or a root may have recurrent meaning that can be quite underspecified. Assuming that language users are able to detect such subtle semantic or thematic regularities like the ones identified by Baeskow (Reference Baeskow2006), the semantic representation of submit might be reanalysed as something as including thematic information such as that in (6). Likewise, a word in which the prefix contributes meaning may be stored as (14), in which only the prefix is coindexed to part of the semantic representation. Similar representations could be posited for words in which the root contributes meaning to the whole, but not the prefix (see (8)).

Cases such as those seen in (9) and (10) in which the prefix contributes meaning but is attached to a bound stem may be analysed as word-level constructions if the semantic contribution of the prefix is perceived to be the same as that found in constructions with free bases, and the base can be attributed a syntactic category. Thus, the lexical entry for a word like cohabit could be analysed as in (15).Footnote 20 We represent the fact that the meanings of the prefix and the stem are perceived through coindexation, shown as α and β, but indicate ‘[…]’ at the semantic level to show that there are semantic idiosyncrasies that are specific to that word (e.g. ‘living together as if married’ – first sense given by Dictionary.com).

Once again, analytic listing does not necessarily mean that word-level formations are compositional at all levels of representation, but that words that are analytically listed are computed as constructs at the phonological level. For instance, compounds are treated as word-level constructs, and it is well-established that they may drift away semantically from the meaning of their constituents. Possibly the most extreme case of this is place names in which the semantics of the constituents are underspecified or entirely absent (e.g. Cambridge, Washington, Westminster), even though they often have the phonological properties of word-level constructions (see Dabouis Reference Dabouis2024, Köhnlein 2015). This is also true of some phrase-level constructions such as phrasal idioms (e.g. to pull X’s leg) which have non-compositional semantics and thus require lexical storage (Bermúdez-Otero Reference Bermúdez-Otero and Trommer2012).

On top of having stored stems and words which have constituent structures involving prefixes and bound roots, language users may posit lexical entries for those constituents, as the lexicon is assumed to be highly redundant in Stratal Phonology. Thus, those entries may specify recurrent semantic features, allomorphs or the preferred nominalizing suffix for roots.

We have already mentioned the idea that the generalizations that are related to opaque prefixed words are lexical redundancy rules that are typical of stem-level phonology. Such generalizations are typically semiproductive and sustain lexical exceptions. To capture most of the phonological generalizations detailed in §2.1, we could use an optimality–theoretic framework (Prince & Smolensky Reference Prince and Smolensky1993) using a constraint requiring the alignment of a minimal foot projection with the left edge of the root (to account for root–initial primary stress in verbs, adjectives and adverbs and for the absence of reduction – arguably secondary stress – in trochaic disyllabic nouns) and one requiring that prefixes are not footed (to account for vowel reduction and the overall ‘stress-repellent’ behaviour found for secondary stress and in verbs, adjectives and adverbs).Footnote 21 We would also require machinery to capture the difference between nouns and other syntactic categories. One solution would be to use cophonologies, as proposed by Bermúdez-Otero & McMahon (Reference Bermúdez-Otero, McMahon, Aarts and April2006), in which the two constraints that refer to prefixes and roots would have different rankings or weights. A representational solution could also be considered. For example, Hammond (Reference Hammond and Durand1999: 278–82) assumes that unsuffixed verbs and adjectives end in a catalectic suffix. Only a detailed exploration of those two solutions based on large datasets can help determine which analysis should be favoured. In both cases, the two constraints would have to be dominated by other constraints, for example, to enforce secondary stress on the prefix if two syllables precede primary stress (e.g. còrrespónd, èntertáin, ìnterséct) or if a stem-level suffix requires primary stress to be on the prefix (e.g. ádvocate, démonstrate, súbjugate). Given the non-categorical distributions of the data discussed in §2.1, probabilistic models using weighted constraints (e.g. Goldwater & Johnson Reference Goldwater, Johnson, Spenader, Eriksson and Dahl2003, Pater Reference Pater2009b) could be the best tools to capture those distributions. We leave the details of such an analysis to future research.

5. Conclusion

In the phonological literature, English opaque prefixed words are usually seen as simplex words and their internal structure is seen as unlearnable. We have seen that this view, which would predict similar patterns for such words and words without any morphological structure, is unsupported by the available evidence. These words display phonological behaviours that are distinct from those of non-prefixed words, have specific allomorphies and selectional restrictions, appear to be treated like words with free morphemes in early visual decomposition and impact stress placement in the reading of disyllabic words. Moreover, we have seen that, while many prefixed words have non-compositional semantics, even the most opaque roots may actually have ‘skeletal’ thematic information, as argued by Baeskow (Reference Baeskow2006).

We have addressed the issue of learnability by arguing that language users probably use the same mechanisms to detect opaque morphological structures as the ones that they use to detect productive morphological structures, the main one being systematic comparisons across classes of words sharing form and, at least sometimes, meaning. However, given the more restricted – especially semantic – overlap across words sharing the prefixes and roots discussed in this paper, we have argued that it is possible that not all language users eventually detect such constituents and that those that do probably do it late.

We have also proposed what the lexical entries of different types of prefixed words could look like, and we have appealed to the notions of analytic and nonanalytic listing from Stratal Phonology and coindexation among different levels of representation in lexical entries. In such an approach, there need not be coindexation between all levels of representation, and so items may be semantically non-compositional but complex at other levels of representation. We have suggested that the generalizations required to capture the phonological behaviour of opaque prefixed words are lexical redundancy rules that are typical of stem-level phonology.

These hypotheses on synchronic analysis predict two types of mismatches with etymology: historically non-prefixed words treated as prefixed, and historically prefixed words no longer perceived as such (see Fournier (Reference Fournier1996)). The boundary between opaque prefixed words and truly simplex words should also be investigated in more detail.

It seems to us that the next steps are to continue accumulating phonological, morphological and psycholinguistic evidence which may inform us on how language users process opaque prefixed words. In particular, more evidence from psycholinguistics would be welcome, as a lot of the evidence on morpho–orthographic segmentation comes from studies on suffixed words, and we have reviewed the only studies that we know of which deal with prefixed words. Therefore, more evidence on prefixed words using various experimental paradigms (lexical decision, ERP, segment shifting) would help consolidate existing findings. Moreover, it will also be crucial for future studies to integrate the diversity of the semantic configurations found in prefixed words because, as we have seen, the semantic contribution of prefixes and roots can vary drastically from one word to another. Promising avenues of research may also be to explore more subtle semantic similarities among words sharing prefixes and roots using Distributional Semantics and semantic vectors (Widdows & Cohen Reference Widdows and Cohen2010) and, on the formal side, to evaluate the contribution of opaque prefixes and roots to computational models modelling stress, such as analogical models or Naive Discriminative Learning (Baayen et al. Reference Baayen, Milin, Durdević, Hendrix and Marelli2011). Finally, it would also be interesting to investigate individual differences between language users and to establish which factors seem to affect how likely they are to process opaque prefixed words like complex words (e.g. vocabulary size, morphological sensitivity, age, education).

As for models of the morphology–phonology interface, the evidence that we have reviewed shows that reference to semantically opaque constituents should be allowed. Any model which seeks to maintain the view that opaque prefixed words are simplex words should provide an alternative account for the results reported in this paper. The evidence discussed in this paper shows that the range of possible morphological structures that may impact phonology should be expanded to include less productive and semantically transparent structures, possibly in other languages (at least languages closely related to English such as Dutch or German). There is already an emerging line of research on place names (Dabouis Reference Dabouis2024, Köhnlein 2015, Mascaró Reference Mascaró2016), which shows clear phonological evidence of morphological complexity (e.g. stress patterns that are typical of complex words, deviant phonotactics) despite the semantic opacity of word-internal constituents. In that case too, the recurrence of the internal constituents of proper names, especially final constituents, probably plays a key role in the identification of internal structure.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their constructive remarks and suggestions, which have helped us to considerably improve this paper. We would also like to thank the colleagues with whom we have exchanged extensively about those issues over the past few years, most notably Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, the members of the ERSaF project, Sabine Arndt-Lappe, Ingo Plag, Marie Gabillet and Aaron Seiler, and the audiences of the 2017 French Phonology Network conference (RFP) and Old World Conference in Phonology (OCP) conferences, to whom early versions of this research have been presented. All errors are ours alone.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the Agence National de la Recherche (ANR-21-FRAL-0001-01) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (AR 676/3-1) for the ERSaF (English Root Stress across Frameworks) project.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.