Introduction

Active labour market policies (ALMPs) were introduced in the Global North in the mid-1990s to improve the employability of job seekers, and subsequently much research on employment has focused on the supply side of the employment equation (Bell and Blanchflower, Reference Bell and Blanchflower2011). Despite growing attention to demand-side mechanisms in explaining the success and failure of ALMPs, several recent contributions argue there is lack of systematic evidence regarding why and how employers engage with and participate in ALMPs (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018; Orton et al., Reference Orton, Green, Atfield and Barnes2019).

In line with van Berkel et al.’s (Reference van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017) programme for future research on employer engagement, we investigate employer motivation and behaviour by focusing on Work Training, drawing on evidence from a multi-method Norwegian study. Work Training is by far the most commonly used labour market measure for young people in Norway (NAV statistics, 2016). More specifically, first, we explore employers’ reasons and justifications for engaging with ALMPs by offering work training programmes for young candidates (van Berkel et al., Reference van Berkel, Ingold, McGurk, Boselie and Bredgaard2017). Second, we investigate employer behaviour through observations of offered work training and subsequent hiring of work training candidates. We address motivation as well as structural factors related to industry, sector, company size and commitment to work inclusion policies. Previous research focusing on employer engagement concluded that, to increase employer engagement in ALMP schemes, local job centres must improve their outreach activities (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018). In this article, we argue that this is a necessary but not a sufficient strategy. Our findings indicate that structural constraints impact employer engagement, in terms of both training and hiring.

In an international context, the Norwegian case is interesting for several reasons. The Norwegian economy and its labour market are, in a comparative perspective, very well-functioning, albeit with particular challenges for young job seekers. Despite the well-functioning economy and low levels of unemployment, Norway’s youth-to-adult unemployment ratio is among the highest in Europe, placing young people in an adverse position (Hyggen et al., Reference Hyggen, Kolouh-Söderlund, Olsen, Tägtström, Halvorsen and Hvinden2018). Thus, the potential benefit of ALMPs is particularly high. Norway has, alongside its Scandinavian neighbours, been a pioneer in using activation measures (Lødemel and Trickey, Reference Lødemel and Trickey2001) and has a long tradition of work-oriented measures for youths. One of the main strategies for increasing the inclusion of young unemployed people in Norway is to apply ALMPs, in particular Work Training. This measure is implemented in the open labour market and gives registered unemployed people the opportunity to gain work experience for up to one year. Administered by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare administration (referred to as NAV), in this program, NAV caseworkers are appointed to follow up with candidates and employers (NOU, 2012; NAV, 2016). Work Training is considered easily available and inexpensive, and is seen as one of the most effective ways of improving a person’s employability (Spjelkavik, Reference Spjelkavik2016). This is in line with a trend towards providing vocational training in ordinary work places rather than by sheltered enterprises (Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, 2012–2013). However, previous contributions in the field argued that ALMPs may worsen precarity without achieving the stated goal of increasing labour market participation, because of administrative failure and employer discrimination (Greer, Reference Greer2016).

Despite being one of the most widely used measures to include young people in the labour market, previous evaluations of Work Training have found few positive effects on subsequent employment (Hardoy, 2003; Reference Hardoy2005; von Simson, Reference von Simson2012; Zhang, Reference Zhang2016). The mechanisms behind these effects (or lack thereof) are not yet fully understood. However, recent studies indicate that employers perceive a history of unemployment and participation in ALMPs such as Work Training as negative signals of productivity and thus associate these applicants with higher risk than other job candidates (Hyggen, Reference Hyggen2017; Parsanoglou et al., Reference Parsanoglou, Yfanti, Hyggen and Shi2019). Moreover, business cycles have been found to affect employer involvement in ALMPs (Ingold and Stuart, Reference Ingold and Stuart2015), but in contrast to most European countries, the demand for labour in Norway has been largely unaffected by the global recession, and thus employer involvement should be relatively stable. In contrast to the UK, for instance, Norwegian employers play an important role in developing and sustaining labour market policies through the so-called tripartite agreement (Pedersen and Kuhnle, Reference Pedersen, Kuhnle and Knutsen2017). However, Norwegian authorities are reluctant to impose obligations on employers (Halvorsen and Hvinden, Reference Halvorsen and Hvinden2018), leaving ALMP engagement among employers largely dependent on voluntary commitment (Aksnes, Reference Aksnes2019). This context of, on the one hand, a well-functioning labour market with established relations between the actors and, on the other hand, relatively large challenges for young unemployed people, and soft labour market policies in the field, makes it interesting to study empirically how Norwegian employers engage in ALMPs.

ALMPs and employer engagement

A range of theoretical models exist in the literature to explain employer behaviour and engagement with ALMPs, and they do not pertain only to risk. Bredgaard and Halkjær (Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016) identified six promising candidates for a theoretical grounding of the motivations of employers to participate in ALMPs: neo-classic economic theory, the theory of collective action, power resource theory, varieties of capitalism, institutional theory and corporate social responsibility (CSR) theory. The last theory has received the most recent research attention in the field of labour market inclusion (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2014; van der Aa and Berkel, Reference van der Aa and van Berkel2014). McGurk (Reference McGurk2014) sets out a typology of employer engagement in ALMPs and proposes that organisations who rely heavily on a large supply of low-wage, low-skill labour for their core operations are most likely to engage. In addition, he suggests those that place a strategic premium on customer service are more likely to develop strategies to retain and internalise long-term unemployed people, as core employers. His findings strongly support the first proposition.

In her work, Simms (Reference Simms2017) identifies two sometimes competing logics that explain employer actions related to engaging or not engaging in labour market policies to help young people access work. These are interests surrounding human resources (the relative costs and benefits of recruiting staff, developing skills, etc.) and corporate social interests (social reputation of the company, etc.). This is in line with previous research from Norway. In a comprehensive qualitative study of work inclusion, Nicolaisen (Reference Nicolaisen2017) identifies how employers in specific industries relate to Work Training and what kind of support they request from NAV. Employers seem to be motivated to offer Work Training because they want to be socially responsible and because they see it as a means to obtain cheap labour.

Research shows that larger companies are more willing and capable in terms of hiring young people in general (Barber et al., Reference Barber, Wesson, Roberson and Taylor1999) and young people with disabilities in particular (Jasper and Waldhart, Reference Jasper and Waldhart2013; Song et al., Reference Song, Roberts and Zhang2013). Larger companies are also more likely to actively recruit people with disabilities (Houtenville and Kalargyrou, Reference Houtenville and Kalargyrou2012). This may be related to the fact that the relative impact of one new worker on a large company is less than their potential impact on a smaller one. In addition, larger companies often have more developed HR departments, with more resources and knowledge available to facilitate potential training. Osterman (Reference Osterman, Bartik and Houseman2008) proposed that employer engagement depends, among other contextual factors, on an established HR function. Established HR functions are more likely to be found in larger businesses.

Sector- or business-specific skill composition has been identified as one explanation for differences in engagement with ALMPs. A recent Danish survey found that, as the share of unskilled workers in a firm increases, the likelihood that the firm will hire an unemployed person from a wage subsidy scheme decreases (Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016). The share of employees covered by collective agreements, the economic situation of the firm and the nationality of the primary ownership are also found to be important factors influencing participation in ALMPs (Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016).

Employers’ perceived risks when hiring young people with unknown productivity may be reduced by involving a third party in the hiring process (i.e. a public or private recruitment company) or by seeking support from public employment services (von Simson, Reference von Simson2012; Hyggen et al., Reference Hyggen, Imdorf, Shi, Sacchi, Samuel, Stoilova, Yordanova, Boyadjieva, Ilieva-Trichkova, Parsanoglou, Yfanti, Hvinden, Hyggen, Schoyen and Sirovatka2019). These factors may therefore increase the chances of an employer committing to training or hiring a candidate after Work Training. In Norway, the Inclusive Working Life Agreement (IA agreement) has been an important tool for employer commitment to ALMPs. The IA agreement is voluntary for employers and gives businesses access to practical and economic support via regional Employment Support Centres administered by NAV (Mandal and Ose, Reference Mandal and Ose2015). Since its adoption in 2001, about 26 per cent of businesses in Norway have signed the agreement, the majority of which are large and/or public companies (Regjeringen, 2018).

Based on this literature overview, the article addresses the following research question: How do employer motivation and structural factors impact employer engagement with Work Training and subsequent hiring? The ‘how’ question will be explored via qualitative employer interviews, whereas the investigation into structural factors will be based on survey data.

Methods and sample

To investigate employer engagement with ALMPs, we used a mixed-methods design incorporating both an employer-centred telephone-based survey and qualitative interviews. In collaboration with representatives from the welfare and employment directorate, from a regional Employment Support Centre and from an employers’ organisation, we developed questions about the characteristics of employers and their use of Work Training. In the qualitative interviews, the same questions were used to structure a conversation around the topic, to give more in-depth insight into employers’ experiences. The Data Protection Official at the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD, project no. 51254) reviewed the survey questions, the interview questions and the consent form to ensure adherence to ethical research guidelines.

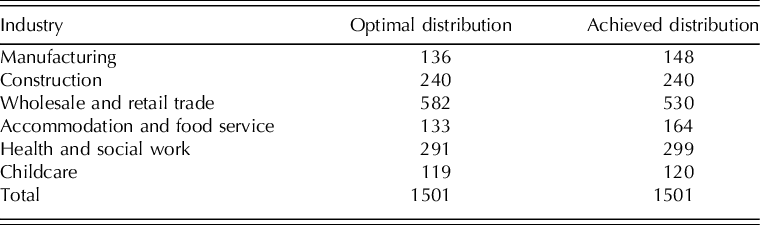

The survey was implemented on a sample of Norwegian businesses from mid-September to mid-October 2017. The sample, drawn from the bizweb database, Footnote 1 consisted of businesses with five or more employees, representing six industries. The six industries were manufacturing (NACE Footnote 2 10-33), construction (NACE 41-43), wholesale and retail trade (NACE 45-47), accommodation and food service (NACE 55-56), health and social work (NACE 86-88 excluding 88911) and childcare (NACE 88911). The survey targeted the general manager or the human resources manager of the business. A total of 1501 survey responses were collected (see Appendix Table A1 for an overview), resulting in a response rate of 34.7. The various industries were adequately represented in the dataset. However, due to some skewness in responses between branches, a weight ranging from 1.1 (retail trade) to 0.81 (accommodation) is applied in the general analyses.

Table 1 Odds ratios of recent experience with candidates in Work Training and hiring candidates. Binary logistic regression (n = 1452/n = 752)

Notes: *** p < 0.01, ** p < 0.05, *p < 0.10

The interviews were conducted in the fall of 2017, and each interview lasted for about an hour. We recruited interviewees to the study in a strategic way, as we were interested in talking to employers who were concerned with work inclusion and employers who had recently had vacant positions. We obtained a good range of variation in employer experiences, interviewing employers with different attitudes and narrated practices of recruiting and including young unemployed people. (For an overview of the interviewees, industries and size of the businesses, see Appendix Table A2.) Seven interviews were conducted face to face, while four were carried out over the phone due to geographical distance. We recorded and transcribed the interviews. Interviews were reviewed and coded using a qualitative data computer software package (NVivo). Focusing on employers’ stories about Work Training, we identified sub-codes relating to such issues as employers’ perspectives on NAV’s mapping of the candidate and conditions relating to the actual Work Training happening in the business, as well as the preparation by employers.

A narrative approach guided both the interview conversations and the analysis of the qualitative data. Our aim was to gain insight into employer engagement, attitudes and narrated practices of including young people by offering Work Training. We focused mainly on their experiences, which means that we understand employer stories as meaning-making practices which to some extent give access to their engagement and attitudes. ‘Stories are usually constructed around a core of facts or life events, yet allow a wide periphery for the freedom of individuality and creativity in selection, addition to, emphasis on, and interpretation of these “remembered facts”’ (Lieblich et al., Reference Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach and Zilber1998: 8). This means that the interviews do not necessarily give a complete picture of employers’ experiences with providing Work Training. Nonetheless, the interviews provide subjective, narrated experiences of how some employers in certain industries engage in ALMPs such as Work Training.

The methods applied have limitations. There may have been a certain selection bias in who chose to participate, among both those who responded to the survey and those who agreed to be interviewed. We had no opportunity to investigate representativeness as such among those who chose to participate in the survey. The answers to our questions are, therefore, not necessarily generalisable, but the answers do provide insight into what matters are important among those who responded.

Findings

Motivation: why do companies offer Work Training?

The interviews with employers provided insight into two reasons why companies offer Work Training. The first reason is in line with the purpose of Work Training as outlined by NAV: ‘Work Training should aim to increase the candidate’s qualifications by giving job experience’ (NAV, 2016). The second reason is that Work Training was regarded as a recruitment tool.

Employers offering Work Training to provide work experience said they wanted to give people a chance to acquire workplace experience within what they termed ‘a safe frame’. Providing work practice and a good working environment would help the participants ‘feel dignity’, as one manager (interview 05) explicitly stated. Employers recognised that NAV candidates often had complex challenges and problems. Having a job was acknowledged as something very significant, as a job is associated with being included in society, with being able to use one’s competence, and with proving one’s worth. Providing Work Training therefore gives people the opportunity to feel socially included.

To offer a successful Work Training period – one that would provide the candidate with proper work experience in a safe environment – employers emphasised the need to be well prepared, which included involvement of their staff and preparation for the execution of job tasks by the candidate. Regarding the former, a shopkeeper (interview 01) stated that he was reliant on his staff for the Work Training to be successful. Therefore, he always included the staff in decisions regarding an offer of Work Training. He emphasised that although he himself played a significant part in providing follow-up once the candidate was in his shop, the everyday work of the candidate would largely be executed in collaboration with the rest of his staff. As many of his staff had formerly been Work Training candidates themselves, they were mostly positive about such inclusion. A kindergarten manager (interview 04), in contrast, emphasised that in certain periods (such as those with a high prevalence of absence due to sickness), he would not take on the responsibility of offering Work Training, as his staff already had too much to deal with.

In two interviews, both with employers in the private sector, the offering of Work Training was explicitly recognised as a way of recruiting staff. Thus, a clear aim was to offer the candidate a job in the company after the Work Training period was over. A shopkeeper (interview 01) stated this explicitly: ‘The Work Training is the world’s best job interview’. Instead of being given one chance at a formal job interview, which may last less than an hour, a candidate is given three to six months (or up to a year) to show their abilities. The shopkeeper said that for the last two years he had not placed any job listings, but rather had recruited through Work Training. If he did not have any vacancies after a candidate finished the Work Training period (and he would otherwise have offered them a job), he recommended them to other companies.

The hotel directors (interview 08) assumed that about half of their Work Training candidates would be offered a job. In their earliest interactions with the candidates, they stressed that they would not be able to guarantee a job offer, but would nevertheless emphasise that ‘if you work hard, we will help you find a job’. Furthermore, the directors emphasised the transferable nature of hotel jobs. For example, if the candidate receives their training in the kitchen, they will gain skills that qualify them to work in any of the kitchens in that chain of hotels, as the job tasks are standardised. There would always be other hotels looking for staff, even if the one where the training occurred was not. As Work Training required a lot of effort (in terms of both time and money) from hotel staff, the directors viewed the offer as an investment which would eventually lead to a hire, assuming a successful candidate.

Behaviour: what characterises employers who offer Work Training and subsequently hire?

In the first stage of the survey analyses, we explored the characteristics of employers who have experience with Work Training candidates and employers who have hired candidates with a history of Work Training.

Figure 1 shows the share of employers who have had Work Training candidates. It also shows the share of employers who have hired candidates after a period of Work Training. Fifty-three per cent of the businesses included in the survey had experience with Work Training candidates during the last two years. Thus, we can see that the majority of Norwegian businesses in the six fields have recent experience with candidates in Work Training. The proportion is highest in childcare and health and social work and lowest in construction and manufacturing.

Figure 1. Proportion of employers who have experience with candidates on Work Training and proportion of employers who have hired a candidate after Work Training (by industry; N = 1458/N = 754).

Employers who had recent experience with Work Training were asked whether any candidates were hired after the end of their Work Training period. About half stated that one or more of the Work Training candidates had been hired. Figure 1 shows there is some variation among industries regarding the proportion of employers who have hired candidates after Work Training. The highest proportion is found in the wholesale and retail trade, followed by accommodation and food service, and manufacturing. The lowest proportion of employers hiring candidates after Work Training is found in childcare.

A number of factors may affect why employers choose to take on candidates for Work Training and why they choose to hire candidates after a period of Work Training. Here, we explore some of the differences between industries and in the characteristics of the businesses that might help explain this. In general, we are interested in what makes employers willing and able to include young people in Work Training practices and to hire candidates after a period of Work Training. Below, we present an analysis in two steps that includes information on business size, sector, participation in the IA agreement and an indicator of business motivation for inclusion. As an indicator of motivation for engagement we use responses to the survey question ‘To what degree is your company concerned with including young people with psychosocial disabilities?’. The responses range from 1: not at all to 4: to a large degree.

Table 1 presents four models using odds ratios (Exp(B)). The odds ratios are used as measures of association between observed characteristics of the businesses and the odds of recent experience with candidates on work training (model 1 and 2) and hiring candidates (model 3 and 4). Odds ratios higher than one are interpreted as higher odds and odds ratios lower than one are interpreted as lower odds of the predicted outcomes.

Model 1 in Table 1 shows that the odds ratio of recent experience with Work Training candidates is clearly associated with the size of the business. That is, the higher the number of employees, the greater the probability the company includes individuals in Work Training. Compared to small businesses (5–9 employees) medium to large businesses (100–249 employees) have 5.7 times higher odds of recent experience with candidates on work training. The analyses indicate that the effect of business size reaches a limit in medium to large enterprises (somewhere between 100 and 250+ employees).

There is also a statistically significant association between being part of the IA agreement and including individuals in Work Training. Controlling for other factors, businesses with an IA agreement are almost twice as likely to have recent experience with candidates in Work Training as are businesses that are not part of the IA agreement.

Based on the businesses with recent experience of Work Training candidates, we observed that business size and participation in the IA agreement do not affect hiring probability (model 3). We did, however, observe a weak but statistically significant association between the sector type and the probability of hiring candidates after Work Training. Specifically, the odds ratio of hiring is higher in the private sector than in the public sector. This public/private distinction is a key difference between the industries represented by the businesses included in our survey. In manufacturing, construction, retail and accommodation, the majority of businesses are private, ranging from 93.7 per cent in construction to 99.3 per cent in manufacturing. In health and social work (18.5 per cent private) and childcare (55.8 per cent private), there is a greater public/private mix. We use the latter two industries to analyse the potential impact of the public/private divide on the use of Work Training. More detailed analyses reveal there is a greater tendency for private businesses in the health and social work industry (as well as in childcare) to hire candidates after a period of Work Training. The main driver of this tendency is the health industry, where 65 per cent of employers in the private sector have hired a candidate after Work Training (compared to 44 per cent in the private sector). The result remains statistically significant even when controlling for business size and participation in the IA agreement.

In a second step (models 2 and 4), we analyse the importance of motivation for participation and for hiring. The analysis reveals that attitudes and motivation, measured by to what degree the business focuses on including young people with psychosocial disabilities, is important in regard to including young people in training, but not in regard to hiring.

Discussion and conclusion

In this article, we have examined why some employers provide Work Training and what characterises employers who engage in ALMPs and who subsequently hire participating candidates. Interviews with employers provide insight into the motivation of employers – why they are committed to engage in ALMPs. They report providing Work Training to demonstrate their social responsibility. These ‘employers participate from altruistic reasons’ (Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016: 51) and do so because it is the ethically and morally right thing to do. In addition, some found Work Training to be a good recruitment tool. Applying neo-classic economic theory, these employers participate because doing so is in the economic interest of the company (see Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016). Thus, the qualitative analysis shows there may be a mix of reasons why employers engage in ALMPs.

As the survey analysis shows, a large share of the employers reported an inclusive ALMP practice. Half of the surveyed employers reported providing Work Training, and half of these reported hiring former Work Training candidates. Compared to previous international research in the field, these results are relatively positive. In a recent article, Bredgaard (Reference Bredgaard2018) demonstrates that only a minority of Danish employers can be classified as committed employers. A committed employer is defined as one who has ‘positive attitudes and participates actively in ALMP’ (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018: 369). His analyses focus primarily on attitudes and participation and less on structural factors. Looking at the results from our statistical analyses, three main conclusions can be drawn, all of which are tied to structural opportunities and constraints.

First, size matters. Larger businesses have more room to include people in Work Training schemes than smaller ones do. Second, businesses that are part of the IA agreement are more likely to include candidates in Work Training than businesses that are not part of the IA agreement. Third, health and social work businesses in the private sector are more likely to hire candidates after Work Training than are their public counterparts.

It comes as no surprise that size matters in terms of possibilities for including Work Training candidates. Larger businesses are often more visible than smaller ones, and may thus be more obvious choices for local job centres and case workers seeking to place a candidate. In general, regardless of industry, larger businesses have a greater variety of positions to fill and thus more potential space for different kinds of Work Training candidates. In addition, larger businesses have more developed HR divisions, more resources and more experience in HR work. This may facilitate the implementation of Work Training schemes, as there might be a perceived need for at least some infrastructure and resources to be in place before training can begin. A final factor may be that the relative risk of engaging (an assumed) low-productivity candidate is higher for smaller businesses than for larger ones.

Being part of the IA agreement may influence the likelihood of a business engaging in Work Training, in several ways. First, the IA agreement itself indicates a certain social commitment. Second, being a party to the IA agreement may give a company access to better information on the process of being a Work Training host and on the support available, or a more formal commitment to take part in ALMPs.

The observed association between sectors and their respective probability of hiring Work Training candidates is interesting. Our findings support previous work showing that public-sector employers are more likely to participate in ALMPs than are employers in the private sector (Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016). However, this is only true concerning participation, and not in regard to subsequent hiring of a candidate. The relatively large difference between private and public businesses in the health and social work industry may be explained by different functions of the businesses or by different formal demands for qualifications in the public sector. In the public sector, employers must adhere to the qualification principle (Engelsrud, Reference Engelsrud2009), which means that public employers may only employ the formally best qualified candidate, in terms of qualifications listed in the job posting. Employers in the private sector do not have to take this principle into account, and are therefore less constrained in their hiring decisions.

The differences between industries and sectors in the implementation of Work Training and subsequent hiring might be related to skill composition, as suggested in a recent Danish study (Bredgaard and Halkjær, Reference Bredgaard and Halkjær2016). Our findings also support McGurk’s (Reference McGurk2014) typology and results, in that organisations that place a strategic premium on customer service are more likely to develop strategies to retain and internalise candidates as core employers.

In conclusion, we acknowledge there may be considerable scope for improving the outreach activities of local job centres to improve the participation and attitudes of employers in ALMPs (Bredgaard, Reference Bredgaard2018: 375). However, our findings show that similar importance may be placed on efforts towards opening up sectors closed by sector-specific regulations on hiring, and towards increased awareness of structural constraints as well as opportunities.

Finally, we make some suggestions for future research. Recent literature has noted the landscape of active labour market policy is changing, with greater emphasis being placed on the sustainability of job entries and progression opportunities, rather than solely on the job match (Sissons and Green, Reference Sissons and Green2017). Our data do not shed light on the issue of retention. Thus, future studies should examine whether previous Work Training candidates who are subsequently hired stay in the job. By including retention in the analysis, the potential worsening of precarity of the ALMPs put forward by Greer (Reference Greer2016) may be better investigated. Moreover, even using a mixed-methods approach to the field, we have only scratched the surface of how and why ALMPs such as Work Training is applied in practice. The explanatory power of the models is limited, which means that most of the variation in probability of recent Work Training experience and hiring Work Training candidates must be explained along other dimensions. For future research, comprehensive fieldwork would be beneficial to better understand the complex nexus among motivation, attitudes and behaviour in employer engagement and thus pave the ground for better policies for employment inclusion.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Norwegian Labour and Welfare Administration through a Research and Development grant. We would like to thank all the respondents and interviewees for taking part in the study. We would also like to thank Elisabeth Ugreninov for developing the survey and Miriam Evensen for preparing the quantitative data. The two authors contributed equally to this research article.

Appendix

Table A1 Overview of survey respondents

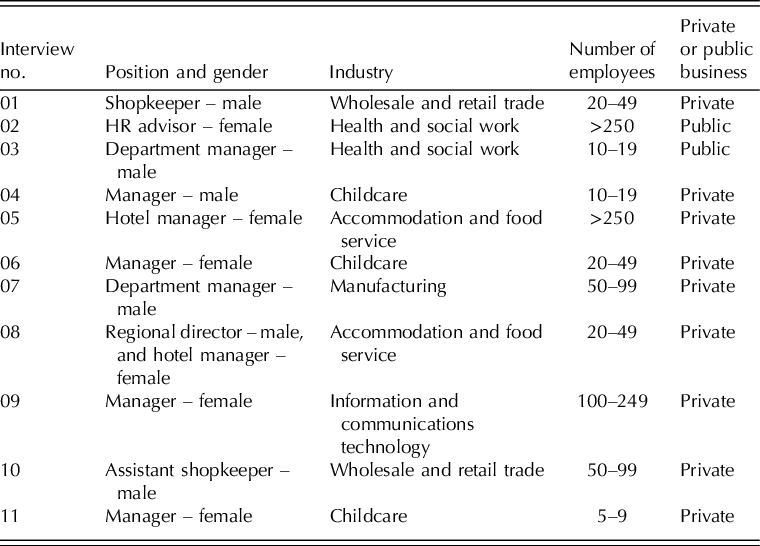

Table A2 Overview of interviewees