Puerperal psychosis is an abrupt onset of severe psychiatric disturbance that occurs shortly following parturition in approximately 1–2 per 1000 deliveries. Despite wide variations in details of definition, it is known that most cases represent triggering by childbirth of episodes of bipolar disorder (Reference Chaudron and PiesChaudron & Pies, 2003). Strikingly, up to a half of parous women with a lifetime diagnosis of bipolar disorder develop an episode of puerperal psychosis in the period immediately following childbirth (Reference BrockingtonBrockington, 1996; Reference Jones and CraddockJones & Craddock, 2001). Such episodes usually require hospitalisation and are associated with substantial functional impairment and risk both to the woman herself and, in rare but tragic cases, to her newborn child.

Unfortunately, inconsistencies in terminology and nosology often result in a failure to provide patients with the information they need to make important decisions about family planning and illness management (Reference Robertson and LyonsRobertson & Lyons, 2003). In this short report we quantify the rates of puerperal and non-puerperal recurrences in a large sample of women diagnosed with clearly defined bipolar affective puerperal psychosis, and provide evidence that a simple clinical variable – family history – may be prognostically useful.

METHOD

The study group comprised 103 women, all UK residents, who had experienced at least one episode of puerperal psychosis. Their mean age at interview was 40 years (s.d.=8). After giving written informed consent, all participants were interviewed by a trained investigator using the Schedules for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN; Reference Wing, Babor and BrughaWing et al, 1990) and case-note information was obtained. Best-estimate episode and lifetime diagnoses were made on the basis of all available clinical information by two independent investigators. The family history interview of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (Reference Spitzer, Endicott and RobinsSpitzer et al, 1978) was used to elicit family histories of mental illness. Each participant's illness history from the first episode of puerperal psychosis (mean age 28 years, s.d.=4.8) was studied in depth and the number and timing of episodes of bipolar illness recorded. Full details of the clinical method are provided by Robertson et al (Reference Robertson, Jones and Benjamin2000).

RESULTS

All participants had experienced at least one episode of bipolar affective puerperal psychosis, defined as onset of a manic or psychotic episode within 4 weeks of childbirth, and all had a lifetime best-estimate DSM–IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) diagnosis of bipolar disorder (n=90) or schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type (n=13). Median follow-up time from recovery from the puerperal episode to interview was 9 years (range 6 months to 33 years). Thirty women (29%) had a previous psychiatric history (defined as DSM–IV major depression, mania or hypomania before the puerperal episode) and 59 (57%) had a positive family history of psychiatric illness, defined as the participant reporting at least one first- or second- degree relative diagnosed with or treated for a psychiatric disorder.

Recurrence rates of puerperal psychotic episodes

Fifty-four participants had a subsequent delivery, of whom 31 (57%; 95% CI 44–69) experienced another episode of puerperal psychosis, and an additional 5 (9%; 95% CI 4–20) experienced an episode of mania, depression or psychosis during pregnancy or within 6 months (but not 6 weeks) of delivery. Using contingency table analysis, neither family history nor personal history of psychiatric illness was a significant predictor of puerperal recurrence in this sample. Of the 39 women for whom the index episode of puerperal psychosis was their first episode, 22 (56%) experienced a further episode following their subsequent delivery, compared with 8 of 15 women (53%) who had experienced other episodes of illness prior to the initial puerperal psychosis (χ2=0.04, d.f.=1, P=0.84).

Risk of further non-puerperal episodes of illness

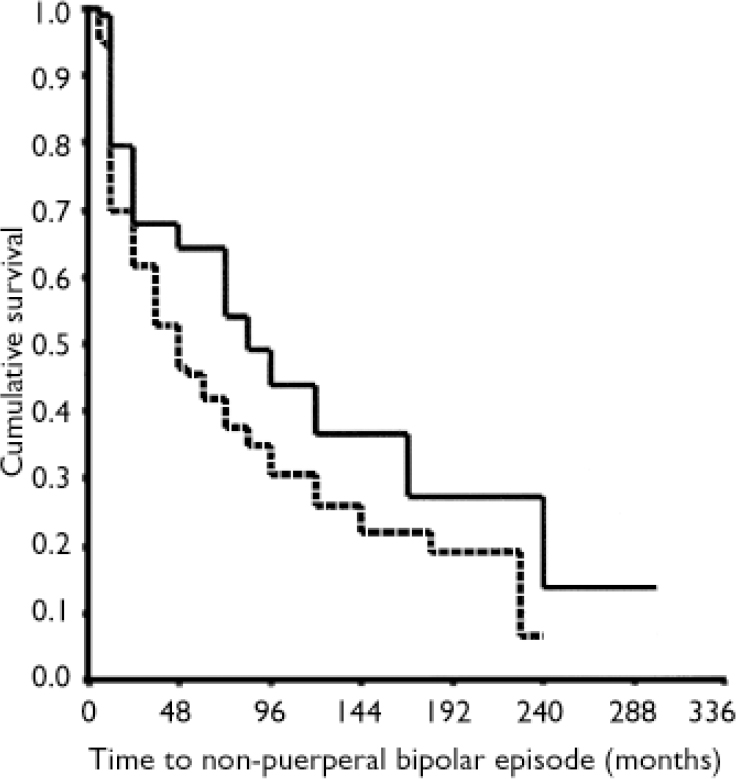

Following the index episode of puerperal psychosis, 64 participants (62%; 95% CI 52–71) experienced at least one non-puerperal affective episode (DSM–IV mania, depression or hypomania) during the period of observation. Because of differing duration of follow-up, Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to examine the influences of personal history and family history of psychiatric illness on time to non-puerperal relapse. A shorter time to non-puerperal recurrence was associated significantly with a positive family history of mental illness (mean survival 4 years v. 7 years; log-rank statistic 6.53, d.f.=1, P<0.01; Fig. 1) and non-significantly with previous personal history of illness (mean survival 4 years v. 6 years; log-rank statistic 1.48, d.f.=1, P=0.22).

Fig. 1 Kaplan–Meier survival curves showing influence of family history of psychiatric illness (positive history, dashed line; negative history, solid line) on time to non-puerperal relapse in women following an index episode of bipolar affective puerperal psychosis. The fixed starting-point was the index episode of puerperal psychosis, the end-point was the study interview. Subsequent pregnancies were recorded as censored values.

DISCUSSION

Our findings are consistent with – and extend – previous research that used a wider phenotypic definition of post-partum psychosis, in finding high rates of recurrence of both puerperal and non-puerperal episodes of major mood disorder (Reference Kirpinar, Coskun and CaykoyluKirpinar et al, 1999; Reference Terp, Engholm and MollerTerp et al, 1999; Reference Robling, Paykel and DunnRobling et al, 2000). We have quantified these risks in a sample of women with clearly defined bipolar affective puerperal psychosis. We found the rates of recurrence following further deliveries were considerably higher than the rates we had reported for women with bipolar disorder in general (26% of deliveries in familial bipolar disorder; Reference Jones and CraddockJones & Craddock, 2001). However, we found no evidence that women whose puerperal psychosis is the first episode of illness have a different risk following subsequent deliveries than women who had previously experienced non-puerperal episodes.

We also provide data regarding the time course of risk for non-puerperal recurrences and evidence that family history may be a useful predictor regarding the timing of risk. The latter finding requires replication in independent samples before it can be regarded as a robust prognostic predictor.

Clinical relevance

Our findings have clinical relevance for the management of women who have experienced or are at risk of an episode of bipolar affective puerperal psychosis.

Family planning

It is vital to be aware of the high risk of puerperal recurrence, but avoiding further pregnancy (as has often been advised in the past) is not a guarantee of avoiding further illness. Many women in our sample reported that they were not made aware of the substantial risks of non-puerperal episodes of illness and made ill-informed reproductive decisions as a consequence. Moreover, we found no evidence to suggest that women who have only experienced a puerperal episode should be considered at higher risk of further post-partum episodes than women who had also had non-puerperal episodes.

Prophylaxis

Although lithium is an effective prophylactic medication in bipolar disorder for many patients, it must be taken regularly, has a narrow therapeutic window, several undesirable adverse effects and is teratogenic to the foetus. Other agents used in prophylaxis – such as sodium valproate or carbamazepine – have similar properties. Decisions regarding prophylaxis of bipolar disorder in women of childbearing age require very careful weighing up of risks and benefits, need to be based on robust evidence, and should be made jointly with the patient. Our data will inform this situation and suggest that a simple clinical predictor (family history) may help to individualise the risk assessment.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the women who participated in this study. This work was. supported by grants from the Wellcome Trust, the West Midlands Regional Health. Authority Research & Development Directorate, South Birmingham Mental. Health National Health Service Trust and the Women's Mental Health. Trust. E.R. was a New Blood Research Fellow and I.J. was a Wellcome Trust. Training Fellow in Mental Health at the time of the study.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.