The southern part of the Polish Jura is a karstic region rich in well-known archaeological cave sites, such as Ciemna, Nietoperzowa, Maszycka, Koziarnia and Mamutowa Cave (Zawisza Reference Zawisza1874; Chmielewski Reference Chmielewski1961; Chmielewski et al. Reference Chmielewski, Kowalski, Madeyska-Niklewska and Sych1967; Kozłowski & Sachse-Kozłowska Reference Kozłowski, Sachse-Kozłowska, Kozlowski, Sachse-Kozlowska, Marshack, Madeyska, Kierdorf, Lasota-Moskalewska, Jakubowski, Winiarska-Kabacinska, Kapica and Wiercinski1995; Valde-Nowak et al. Reference Valde-Nowak2014). Archaeological fieldwork has been conducted in the region since 1871. The caves are mostly located in two major valleys, together over 20km long: the 5km-long Sąspów Valley and the longer Prądnik Valley. The ‘Prądnik knife’, a type of Middle Palaeolithic tool, takes its name from the Prądnik stream. More than 700 caves are known to exist in the region (Partyka Reference Partyka2018).

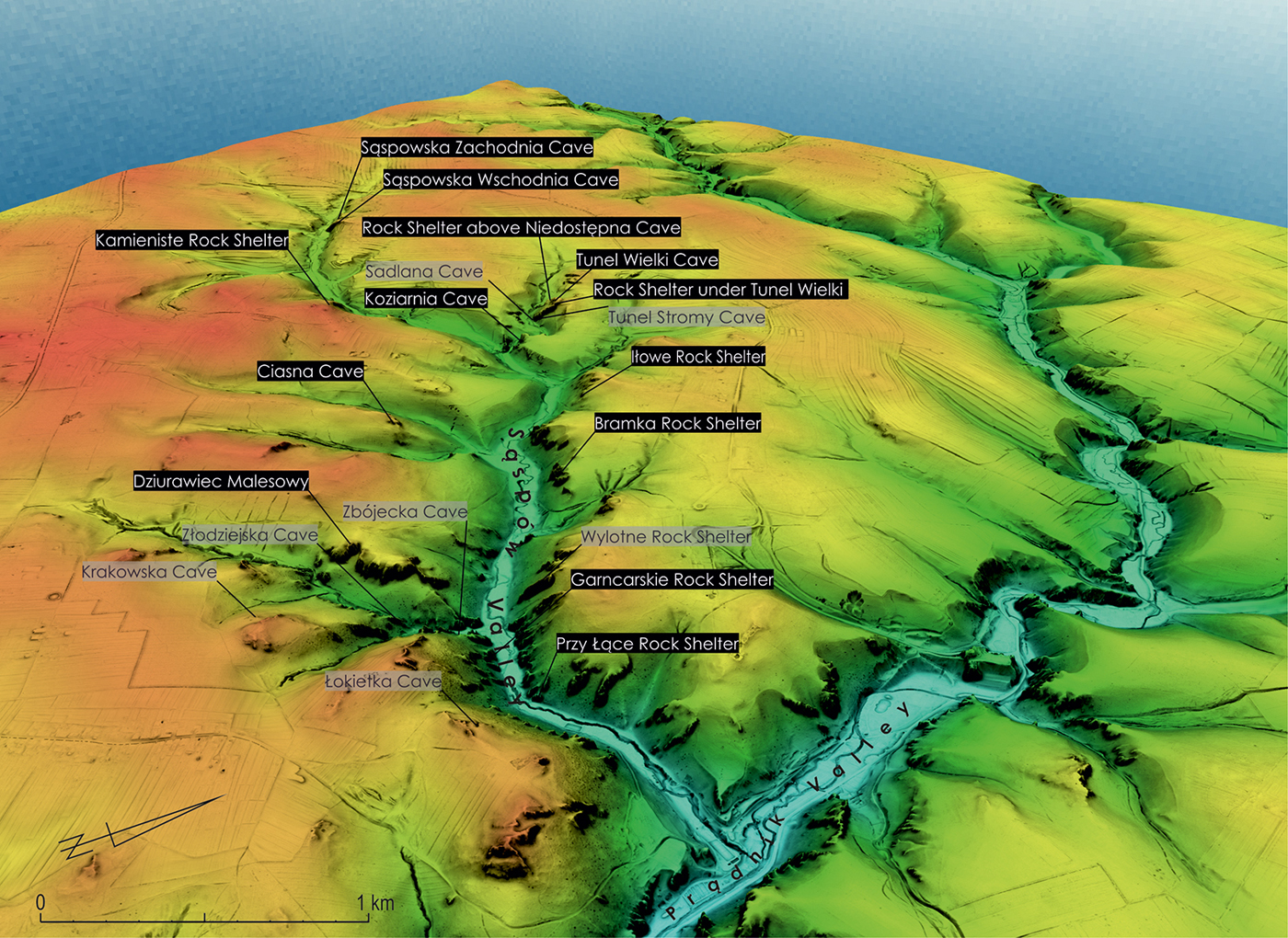

In 1955, Waldemar Chmielewski started to conduct a series of excavations in the southern Polish Jura. He began by excavating Nietoperzowa Cave in Jerzmanowice—a site well known from Ferdinand Römer's earlier work (Reference Römer1883). On the basis of the assemblage, which contained multiple bifacial leafpoints and was radiocarbon-dated to 38 160±1250 BP (Gro-2181), Chmielewski (Reference Chmielewski1961) determined and named a new Middle/Upper Palaeolithic transitional industry called Jerzmanowician. He continued his fieldwork in Koziarnia Cave in Sąspów Valley—another site known from Römer's (Reference Römer1883) work, and the second to yield bifacial leafpoints. Meanwhile, Chmielewski initiated a long-term project that aimed to excavate all of the cave sites in Sąspów Valley with undisturbed stratigraphy. By focusing on a single valley, he aimed to verify the chronological settlement pattern at a microregional scale. Consequently, between 1963 and 1993, Chmielewski excavated 14 cave sites in the Sąspów Valley (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Lidar map of Sąspów Valley showing all known cave sites. Sites included in the current project are marked in black (figure by M. Jakubczak & M. Leloch).

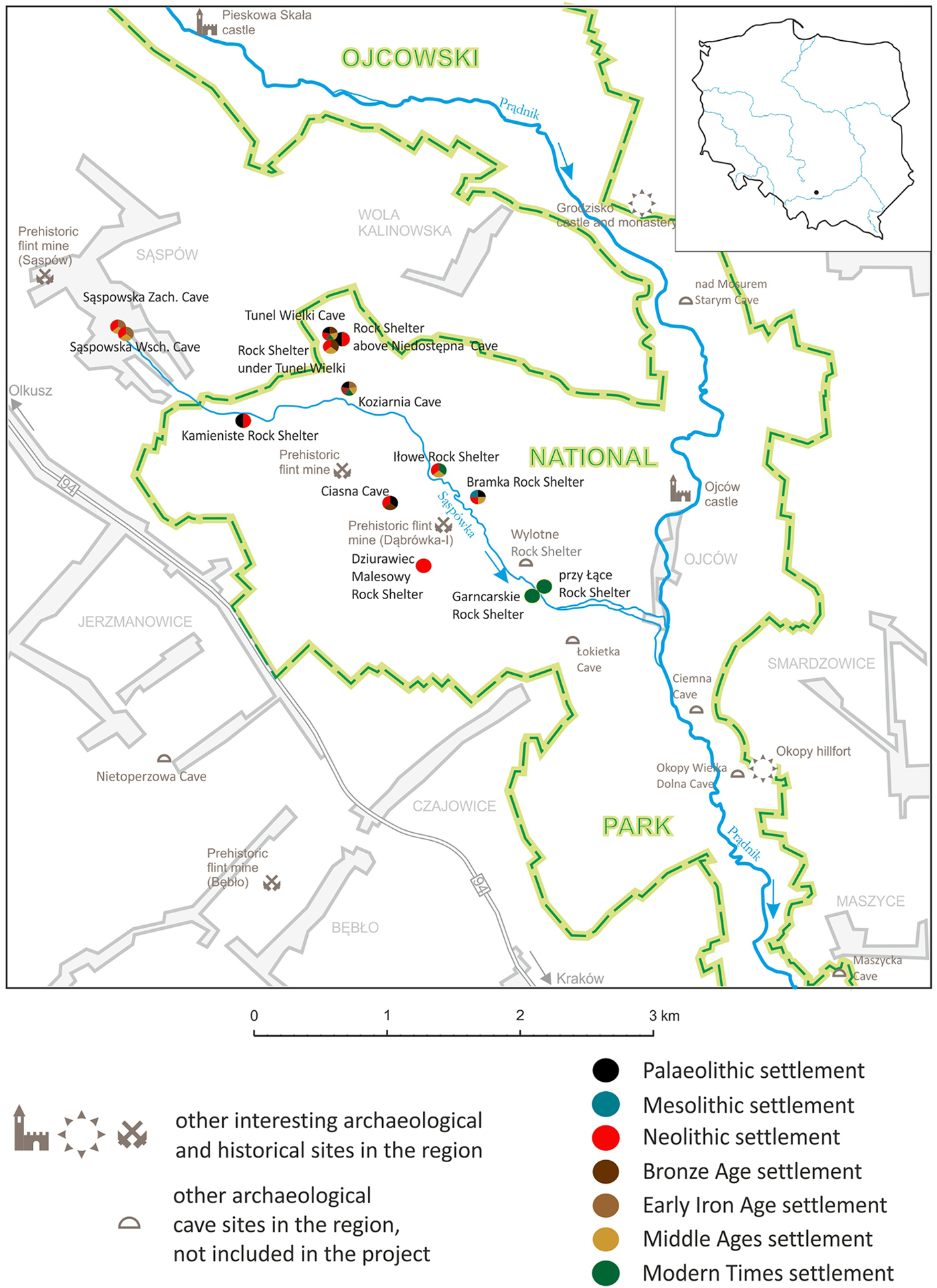

Although Chmielewski was interested mostly in Palaeolithic archaeology, he documented and collected all excavated artefacts, regardless of their date. The aim was to determine the sedimentation pattern within the caves located at different heights in the valley. The majority of sites are multi-layered with a complex stratigraphy (up to 4m thick), well-preserved Pleistocene layers and traces of multiple settlement phases (Figure 2). Only two sites, located very low in the valley, had evidence for a single occupation phase. Notably, outcrops of so-called jurajski flint and associated Prehistoric flint mines, partly contemporaneous with settlement evidence in the caves (Lech Reference Lech1981), were found near the Valley. Although Chmielewski's project was well managed and had great potential, only its geological and palaeontological results were published (Chmielewski Reference Chmielewski1988), along with a brief archaeological introduction.

Figure 2. Sąspów Valley with site chronology (figure by M.T. Krajcarz & N. Gryczewska).

In 2017, a new project was initiated with the aim of completing Chmielewski's work. The project consists of two main parts. The first focuses on analysing Chmielewski's documentation and collections of artefacts and human and animal remains using multiple interdisciplinary analyses, including traceology, CT scanning, electron microscopy (SEM-EDX), chromatography, ancient DNA analyses, ZooMs, isotopic bone analyses, and radiocarbon and uranium-thorium dating. The second part of the project will reopen Chmielewski's old trenches and clean the sections to verify the stratigraphy and collect sediment and palaeontological samples. The planned analyses of these samples, comprising palynological, anthracological, anthropological, palaeontological, GC-MS, sediment DNA and sediment micromorphological analyses, and radiocarbon thermoluminescence and optically stimulated thermoluminescence dating, will determine the microstratigraphy and chronology of certain geological layers and the local palaeoenvironment. Five sites have already been reopened as part of the project: Koziarnia Cave, Tunel Wielki Cave, Ciasna Cave, Bramka Rockshelter and Sąspowska Zachodnia Cave.

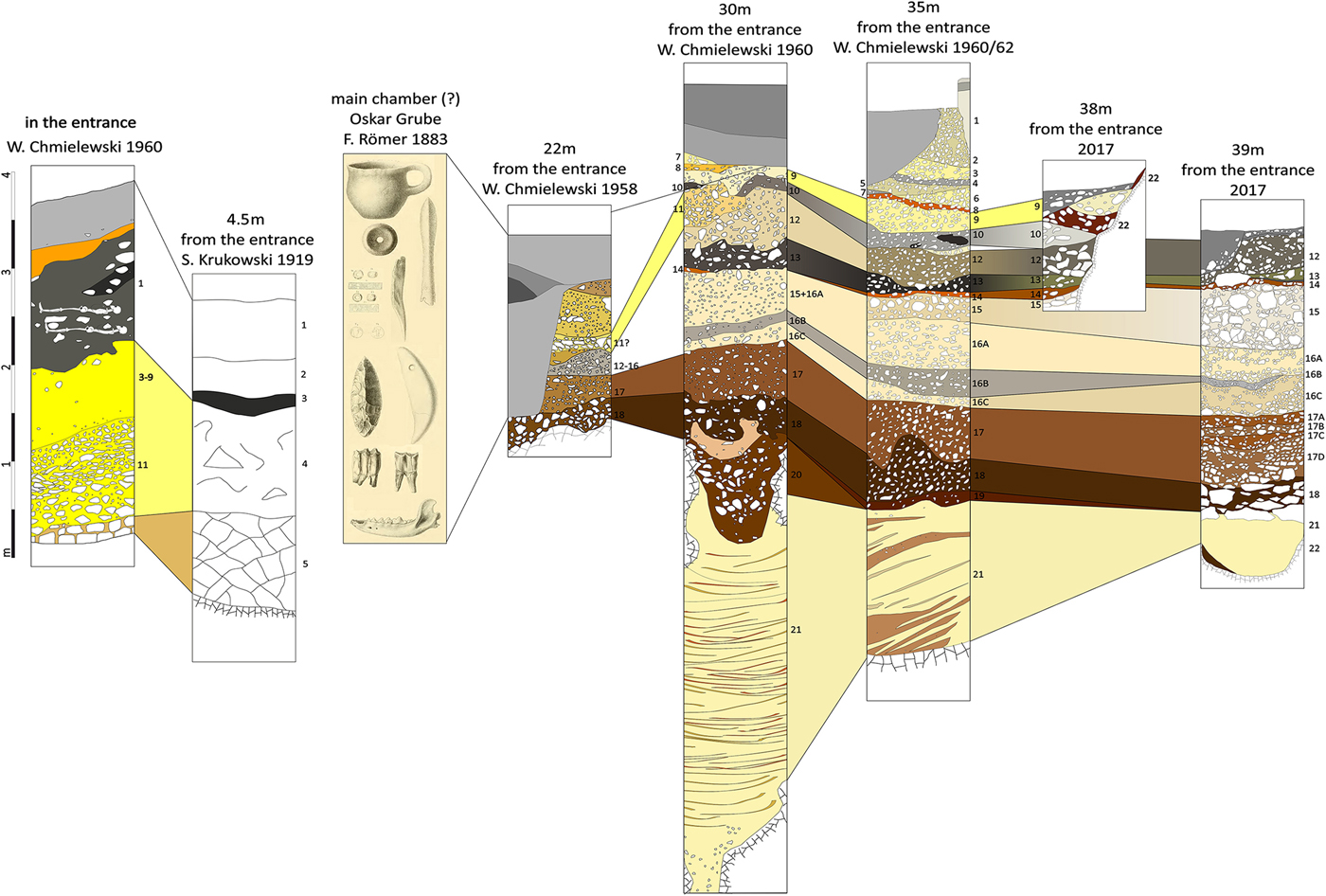

Fieldwork in Koziarnia Cave aimed to determine whether the lithic industry is indeed Jerzmanowician, as claimed by Römer (Reference Römer1883) and Chmielewski et al. (Reference Chmielewski, Kowalski, Madeyska-Niklewska and Sych1967). The new fieldwork focused on defining the chronology of the cave's complex stratigraphy and collecting palaeoenvironmental data (Figure 3). Samples for sediment DNA and GC-MS analyses were also collected. The unidentifiable bones were subjected to ZooMs analyses.

Figure 3. Correlation of stratigraphy from Koziarnia Cave with profiles from old excavations and the trench opened in 2017 (figure by M. Kot).

In Tunel Wielki Cave (Figure 4), the excavations aimed to establish the presence of Middle Pleistocene layers, as suggested by small mammal remains—particularly the presence of Pliomys lenki (Rodentia, Mammalia) (Nadachowski Reference Nadachowski and Chmielewski1988). Our excavations revealed a more complex stratigraphic sequence than previously thought, with numerous re-deposition events documented. A micromorphological analysis of sediments and an analysis of fossil rodent fauna have been undertaken to refine the stratigraphic sequence.

Figure 4. Profile from Chmielewski's excavation in Tunel Wielki Cave (figure by N. Gryczewska).

Ciasna Cave is a multi-layered site with a varied Late Pleistocene assemblage. The homogeneity of the assemblage retrieved by Chmielewski from the Late Pleistocene stratum is ambiguous, due to the presence of both Gravettian and Late Palaeolithic artefacts. In order to determine the layer's chronology, new fieldwork was conducted in 2018. This yielded a rich assemblage of small mammal, amphibian and reptile remains, enabling detailed palaeoenvironmental analyses.

The Bramka Rockshelter is one of two Mesolithic cave sites in Poland. Here, Chmielewski found a juvenile burial within the Lower Holocene layer, but the individual's remains are currently missing. The site was reopened to determine the chronology of the Mesolithic assemblage and to attempt to locate the remains of the previously reported burial. Intensive wet sieving of the old backfill revealed the remains of another juvenile of the same age at death. This will allow us to determine whether this is a Mesolithic inhumation or a later burial dug into the Mesolithic layer (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Human bone from Bramka Cave collected during 2017 excavations (photograph by M. Bogacki).

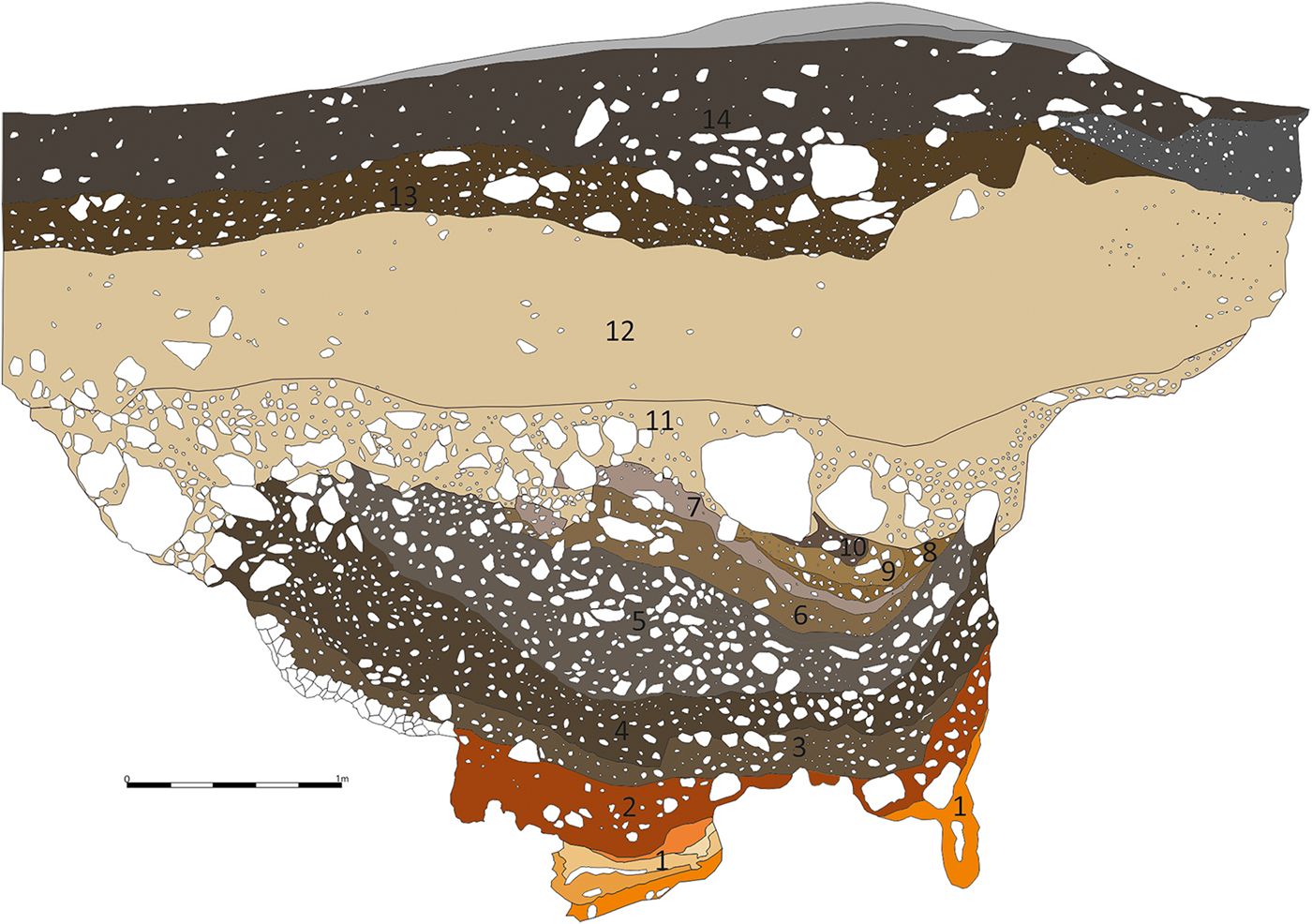

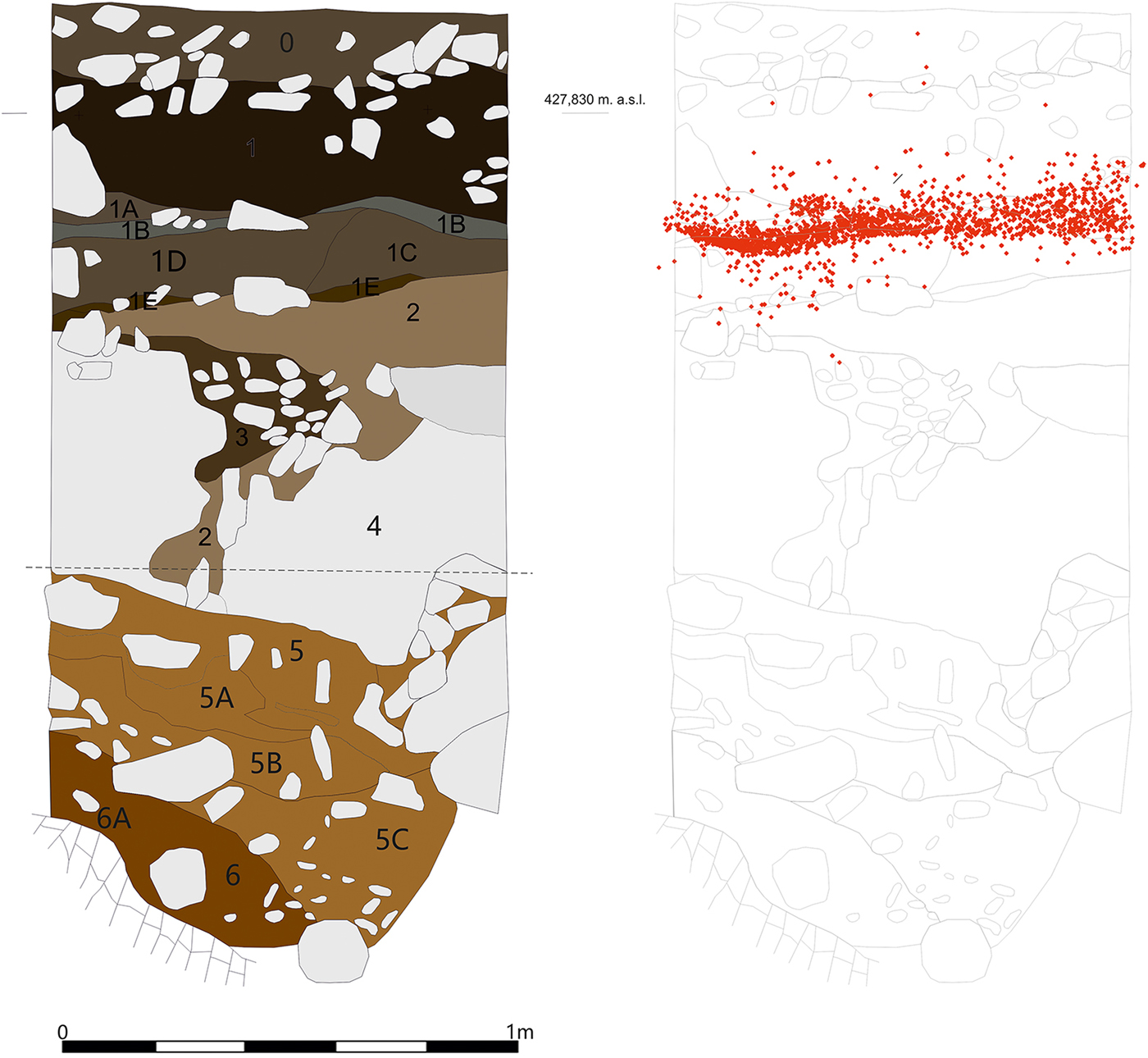

Our most recently excavated site was at Sąspowska Zachodnia Cave, which is located close to the Neolithic flint mines in Sąspów village, and adjacent to the Sąspówka stream. As the whole assemblage from the site is currently missing, fieldwork aimed not only to verify the stratigraphy of the cave, but also to obtain a small artefact collection for further analyses. A 0.2m2 extension of Chmielewski's trench was opened in the cave's entrance, yielding over 20 000 flint artefacts from two Neolithic horizons (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Stratigraphy of Sąspowska Zachodnia Cave with artefacts found in 2018 (figure by N. Gryczewska).

Sąspów Valley has been explored and excavated since the end of the nineteenth century; almost every cave and rockshelter has been investigated for evidence of settlement. The local presence of flint outcrops made the valley an attractive place for Palaeolithic to Early Bronze Age peoples. The valley provides an extraordinary opportunity to study a microregion, and to reconstruct not only the local palaeoenvironment, but also changing diachronic settlement patterns.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Teresa Madeyska, Karol Szymczak and Józef Partyka for their kind help and for providing important information about archival fieldwork. The project is financed by the National Science Centre, Poland (grant 2016/22/E/HS3/00486).