Introduction

In contrast to the paradigm of scientific research that emerged after the Second World War (which ended in 1945) in which ‘the majority of publications are behind a paywall, raw data are hidden, methods ill-described, software unreleased and reviews anonymous’ (Watson Reference Watson2015), ‘open science’ has emerged in the first two decades of the twenty-first century as a better way to practise scientific research.

Researchers following the principles of open science (defined by European researchers who are part of the EU-funded FOSTER project as ‘the practice of science in such a way that others can collaborate and contribute, where research data, lab notes and other research processes are freely available, under terms that enable reuse, redistribution and reproduction of the research and its underlying data and methods’, FOSTER 2023) make all research outputs and methods openly and freely accessible immediately after completion of research along with interoperable and reusable research data (Fecher and Friesike Reference Fecher, Friesike, Bartling and Friesike2014). This, inter alia, enhances the credibility of published research thanks to reproducible results and reproducible methods (Haven et al. Reference Haven, Gopalakrishna, Tijdink, van der Schot and Bouter2022). In closer detail, in open science, a research article is first published on the internet in freely and openly accessible preprint form prior to submission to an academic journal for publication following peer review (Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2020). Compared with overly long peer review (and publication) times eventually resulting in publication behind an expensive ‘paywall’ requiring ever more expensive subscriptions, this liberates the dissemination of new knowledge from all the main problems of conventional publishing of research findings (Xie et al. Reference Xie, Shen and Wang2021; Puebla et al. Reference Puebla, Polka and Rieger2021).

Substantially enhancing the quality and impact of research, the practice of open science offers clear benefits to researchers and to society, including, for example, enhanced opportunities of international collaboration between researchers and a faster pace of innovation (Schimanski and Alperin Reference Schimanski and Alperin2018; Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2021).

The adoption of open science widely differs amid countries, in both economically developed and developing areas of the world. Italy is among the most scientifically developed countries in the world. In a list of countries ranked by number of scientific publications in academic journals indexed by a proprietary research database (Scopus) owned by a large scientific publisher (Elsevier), with 154,304 citable documents published in 2021, Italy ranked sixth after China, the USA, Great Britain, India and Germany, ahead of Japan and Russia (SCImago 2022). Amid the top ten countries in the aforementioned rank, only articles from researchers based in Great Britain received a higher average number of citations (1.45) to articles published in 2021 when compared with those (1.38) from Italy-based researchers (SCImago 2022).

Considering the performance of Italy-based researchers in the adoption of open sciences, however, in 2017 the head of open science at the University of Milan succinctly described its poor state, noting how publishing open access (OA) articles was not yet common, with researchers generally not knowing the foundations and the tools of OA publishing, including widespread confusion between institutional repositories and academic social networks (Galimberti Reference Galimberti2017a). A lack of impactful government policies aimed at promoting open science was also noted (Galimberti Reference Galimberti2017a).

In 2015, an Italian Association for Open Science (AISA) was established as a non-profit organization aimed at encouraging in Italy a culture of open science, including raising awareness among Italian and European legislators of the need for open science in research assessment and intellectual property policies (AISA 2023a). In April 2022, the Association started to publish an ‘open science glossary’ in the form of brief informative entries focusing on the open science lexicon. To date (May 2023), the glossary includes seven entries published between April and August 2022 (AISA 2023b).

The subsequent year, an Italian Open Science Support Group was created as a voluntary working group of professionals (from, among others, the Universities of Milan, Venice, Turin, Bologna, Trento, Parma, Padua, and Trieste) specializing in the areas of research support, libraries, open science, law, and computer science (IOSSG – Italian Open Science Support Group 2022). One of its main achievements was the development of a policy model on open access that was eventually approved by the Conference of Rectors of the Italian Universities (CRUI) (Gargiulo Reference Gargiulo2020). Finally, following similar ‘Reproducibility Networks’ already existing in other countries, including Australia, an Italian Reproducibility Network was established in 2021 (ITRN 2023), which also organizes seminars on open science. It was inaugurated in the same year by a seminar by Nosek on the culture change required for a ‘more open, rigorous and reproducible research’ (Nosek Reference Nosek2021).

Following analysis of the slow uptake of open science in Italy, this study identifies four main lessons that might be useful to scholars and research policymakers engaged in promoting the uptake of open science culture and practices in their own countries.

Institutional Efforts

Early policy attempts to promote the adoption of open science in Italy included the requirement to make openly accessible the publicly funded research articles submitted to the next research evaluation exercise (with an embargo period of 18 or 24 months) by the National Research Evaluation Agency (Miccoli et al. Reference Miccoli, Rumiati and Checchi2020; Redazione ROARS Reference Redazione2020), and a law dating back to 2013 mandating OA for research articles resulting from publicly funded research (Legge 7 ottobre 2013, n. 112 2013). Nearly all Italy-based researchers, however, ignored the law and continued to publish in paywalled journals.

It is enough to review the outcomes of one of the first meetings on OA, organized by the CRUI three years later, to learn that out of nearly 100 universities based in Italy, only 49 had signed the so-called ‘Road Map to Open Access’ in 2014. However, two years later, out of these 49 institutions, only 16 had adopted an OA policy (Masolo Reference Masolo2016), and this despite the fact that, as underlined by Giglia at the same meeting, ‘OA is only 10% of open science’ (Giglia and Minsenti Reference Giglia and Minsenti2016).

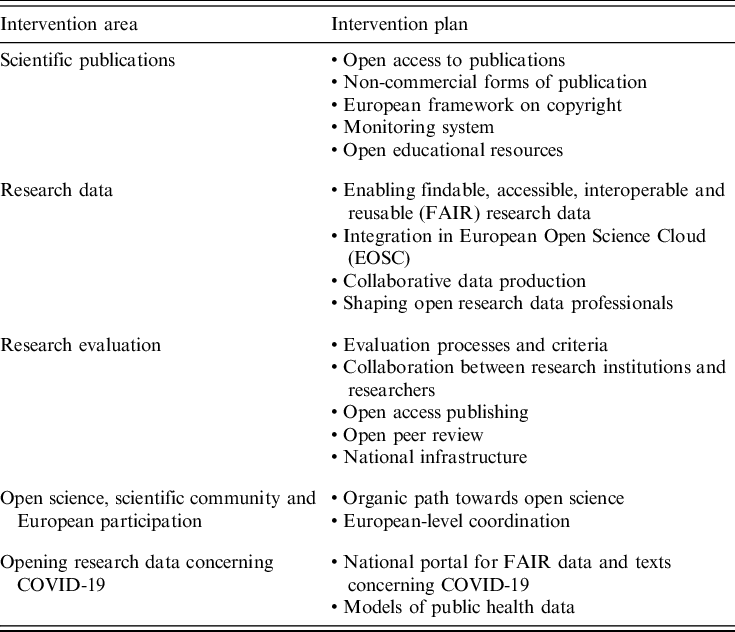

Aiming at ‘developing transparent processes, enhancing research activity, its verifiability, the integrity of research results and proper scientific communication’, in June 2022 Italy’s government published a National Plan for Open Science. The plan focuses on five areas of intervention, including open scientific publications, open research data, and research evaluation (Italy’s Ministry of Research 2022).

This Plan, however, provides no monitoring or verification and no funding, clearly indicating that openness in science remains an unimportant issue both for science policymakers and for most researchers.

Perhaps the main activity in the field of open science in which Italian institutions are seriously engaged is ‘transformative agreements’, namely contracts negotiated

between [libraries, national and regional consortia] and publishers in which former subscription expenditures are repurposed to support open access publishing, thus transforming the business model underlying scholarly journal publishing, gradually and definitively shifting from one based on toll access (subscription) to one in which publishers are remunerated a fair price for their open access publishing services. (ESAC Initiative 2023)

For example, the contract signed with SpringerNature by a consortium representing Italian universities and public research centres amounted to €50 million for five years (2020–2024), whereas that signed with Wiley was worth €42 million for four years (2020–2023) (AISA 2022).

These agreements allowed Italian scientists to publish, respectively, 3800 and 2650 articles per year in hybrid journals without paying the article processing charge. The number of ‘vouchers’ was exceeded in both cases before the year’s end, leading open science scholars in Italy to ask why a public university should promote the service offered by private companies when this would cause further expenses beyond those paid for the transformative agreement (AISA 2022).

In early 2013, ‘aware of the benefits of Open Access for national research in terms of visibility, promotion and dissemination’, the presidents of CRUI and of Italian public research centres signed an agreement ‘to act coordinately in order to achieve the success of Open Access in Italy’ (CNR, CRUI, ENEA, INGV, INFN, ISS 2013).

Eventually, with substantial EU funding made available, a European Open Science Cloud (EOSC) was established in 2015 as an international non-profit organization under Belgian law and with national branches (European Commission 2023). EOSC officially launched in late 2018, and started to provide access to its services via the EOSC portal at www.eosc-hub.eu. In Italy, a Competence Centre on Open Science was thus created within the Italian Computing and Data Infrastructure, a forum of major Italian research and internet infrastructures. The Competence Centre organizes a number of activities including new seminars such as the ‘Open Science Café’ monthly interactive online presentations focusing on a specific theme of open science.

The series debuted in March 2021 with a seminar given by an Italian scholar based at the University of Göttingen (Fava Reference Fava2021). The seminar was held on the Open Research Europe publication platform of the European Commission, for which a €5.8 million, four-year contract was signed on March 2020 with an open research publishing platform owned by a large scientific publisher (Gomez and Kelly Reference Gomez and Kelly2022).

Similarly, by late 2021, a website focusing on open science was launched at www.open-science.it. Managed by professionals of the aforementioned Competence Centre and experts of an Italian Research Council (CNR) institute, the website includes updated information (in Italian) on many aspects of open science and its ongoing uptake.

The Uptake of Open Science in Italy

To understand the state of open access perception amid Italy’s scholars it is instructive to review an online dialogue between an Italy-based researcher and the head of open science at the University of Milan.

Open Access is a business model identified by publishers, generally commercial companies, in response to computerization and the consequent ease of obtaining scientific articles for free, without having to bear the cost (without entering into secularism or not). Fewer subscriptions, less turnover. More Open Access, more turnover. It is therefore not surprising that the governments of some states support Open Access, which is usually paid for at a high price by research funds. In fact, some major publishers have tax offices in the Netherlands, Germany, the UK and bill several billions a year. The maximization of their turnover is therefore in the interest of their governments, which will be able to collect more direct tax revenues both on companies and on the work of employees, as well as on related activities, and from indirect taxation on employee consumption.

Therefore, why should the Ministry of University and Research squander resources to benefit the tax authorities of other states, instead of using the limited resources of Italian taxpayers to benefit the taxpayers of others? (Beccherelli Reference Beccherelli2017).

To which Galimberti responded:

None of the reasons you cited are reflected in the history of open access that arises precisely as a reaction of scientists to the closure and marketing of the contents they produce and freely sold to publishers… When I noticed that in Italy there are few and totally confused ideas, I was referring to interventions like this. (Galimberti Reference Galimberti2017b)

Along with other researchers (Giglia Reference Giglia and Aliprandi2017, Toelch and Ostwald Reference Toelch and Ostwald2018; Steinhardt Reference Steinhardt2020), Pagliaro has suggested that enhancing the uptake of open science requires undertaking new and practice-oriented educational activities aimed at young and senior researchers (Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2020). Similarly, in 2017, a European Commission publication of the Working Group on Education and Skills under Open Science reported a widespread lack of training opportunities for open science in Europe (European Commission 2017). In the same year, Giglia identified the need to develop the culture of open science and promote the use of its new tools, such as the preprint platforms and online repositories to self-archive and to make research articles and other scientific documents, including books, openly accessible (Giglia Reference Giglia and Aliprandi2017).

It is therefore relevant to review selected examples of pioneering education in open science activities held in Italy.

Pievatolo, a political philosophy scholar, gives a three-lesson course on ‘Open science and research data management’ at the University of Pisa, whose presentation slides and handout text in English are freely and openly accessible under a Creative Commons ‘ShareAlike’ licence (for which users are free to share, copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, as well as adapt, remix, transform, and build upon the material or any purpose, even commercially) (Pievatolo Reference Pievatolo2020a). The three lessons focus on open science (‘Scholarly communication and research evaluation: the Open Science Revolution’), research evaluation (‘Irresistible proxies? Peer review and (mainstream or alternative) bibliometric’), and academic copyright (‘Copyright: taking authors’ rights seriously’). The video of a similarly relevant conference lecture held by the same scholar at the University of Rome in 2015 is still available online (Pievatolo Reference Pievatolo2015).

A course on open science in the earth sciences was given by researchers of Italy’s Institute of geophysics and volcanology by late 2020 in collaboration with CNR, OpenAIR and EPOS experts as a series of four lectures held online, again with a strong orientation to practice so as to enable the attendees to learn the tools to practise open science (OpenAIRE 2020). Six months later, another jointly organized online course, this time aimed to CNR scholars and researchers in humanistic and cultural heritage sciences, was organized again as a series of online lectures (CNR 2021), including specific lectures on the main EU-based research infrastructures and research projects for open science in those disciplines.

In 2019, Giglia, head of the Open Science Unit at the University of Turin, held a one-day course aimed at PhD students, librarians and research evaluators at the University of Messina (Giglia Reference Giglia2019). To understand the demand of education in open science in Italy (and in Europe) it is enough to review the seminars (all linked to the self-archived presentation slides) given by Dr Giglia since 2015 to date (Giglia Reference Giglia2023). In 2021, the scholar gave 26 seminars starting in early January with a lectio magistralis inaugurating the Doctorate Schools, again at Messina’s University (‘Open science, il valore della scienza per tutti’), and ending with a seminar (‘Open Science A to Z’) given at the University of Girona, in Spain, in mid-December.

Why Italian Scholars Ignored Open Science

One of the most relevant and practically useful books on open science in Europe was published in Italian in 2017 as freely and openly accessible text (Aliprandi Reference Aliprandi2017). Still, the vast majority of Italian scholars continued to ignore open science. According to Vianello, a work and organizational psychology professor at the University of Padova, the two main barriers to embracing open science practices in Italy would be culture and the extra effort needed to disseminate knowledge according to the open science principles. ‘Our burden is already heavy, pressure to publish is ridiculously high’ he wrote in 2021, so that ‘one really needs to be extremely motivated to follow open science practices’ (Vianello Reference Vianello2021).

One remarkable point explaining a certain naiveté surrounding the open science discourse has been raised by Henry, commenting a 2017 study of Masuzzo and Martens focusing on the need for researchers to learn the new language of open science:

When you write ’One of the basic premises of science is that it should be based on a global, collaborative effort, building on open communication of published methods, data, and results’ you only account for an idealistic view of science. In reality, Open science has an enormous opportunity cost for 1. researchers themselves (hence the importance of credit and citation) 2. institutions 3. countries (somehow secrecy is believed to be a competitive advantage). In the past (and still today to a large extent), science was done for the benefit (prestige, economic or power advantage) of researchers, but also benefactors, universities, nations, etc. not the whole community. I love the idea that we need to insist on the ‘communism’ dimension of research, but we should not ignore the obstacles to Open Science and the fact that funders are mostly national agencies supporting national interests. (Masuzzo and Martens Reference Masuzzo and Martens2017)

We agree with Henry’s preach for realism (Henry Reference Henry2017). It is precisely the little (and even negative) relevance of open science to the academic career that led Italian scholars to delay the uptake of open science practices for nearly two decades. Italy’s researchers were (and most of them still are) unaware that by simply self-archiving their research articles published in paywalled journals in personal or institutional websites (granting to anyone ‘green’ open access) they would substantially increase the number of citations, and therefore the impact of their research (Harnad Reference Harnad2003), on which they are supposed to be evaluated (Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2021).

This reluctance, in brief, has been due to a widespread lack of education on open science (Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2020; European Commission 2017), resulting in a similarly widespread ignorance of its benefits for the academic career (Ciriminna et al. Reference Ciriminna, Scurria, Gangadhar and Chandha2021).

One might object that since Italian universities do not recruit professors according to their h-index or other bibliometric indicators (Gallina and Porfirio Reference Gallina and Porfirio2021), Italian researchers would not be interested in raising their citation-based metrics. This, however, is not the case because the National Scientific Qualification (ASN) necessary to take part in the recruitment and promotion process (from researcher to associate professor, and from associate to full professor) is based on citation-based metrics of publications in indexed academic journals (Poggi et al. Reference Poggi, Ciancarini, Gangemi, Nuzzolese, Peroni and Presutt2019).

It is relevant here to notice that in between 2018 and 2019 Italy lost about 14,000 Italian researchers who emigrated, mainly to other European countries and the USA, where they ‘find a faster career progression and are more confident in their future than Italian researchers in Italy’ (Nascia et al. Reference Nascia, Pianta and Zacharewicz2021). Along with higher salaries, the shift to merit-based recruitment and promotion processes is the solution that has long been identified to end the emigration of Italian researchers and attract talented foreign researchers (Nascia et al. Reference Nascia, Pianta and Zacharewicz2021; Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2007; Abramo and D’Angelo Reference Abramo and D’Angelo2020). This is possible by expanding the research evaluation process to include all three areas of scholarly activity (research, teaching and mentoring, and service to society) and improving the evaluation criteria (Schimanski and Alperin Reference Schimanski and Alperin2018; Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2021).

Note the improvement of the research evaluation system in the third intervention area of Italy’s Open Science Plan (Table 1). The document includes seven recommendations to improve research evaluation (Italy’s Ministry of Research 2022), explicitly calling universities and research centres to adhere to principles of the Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA 2012). Among them, one principle calls for reducing the weight of bibliometric indicators (such as the journal impact factor and the candidate’s h-index) and to include service to society (‘third mission’) and contributions to advance open science.

Table 1. Italy’s Open Science Plan. Interventions areas and intervention plans (adapted from Italy’s Ministry of Research 2022).

Outlook and Conclusions

The history of the uptake of open science practices in Italy in the first two decades of the twenty-first century clearly shows that the goodwill of individuals and small groups was not enough to create fertile ground for the development of open science in Italy, which was and remains a latecomer country. Even the National Plan on Open Science (Italy’s Ministry of Research 2022), which provides no monitoring or verification and no funding, seems to indicate that, apparently for Italian science, the time for openness is not yet ripe. Indeed, the ministry, in March 2023, appointed a steering group tasked to suggest how to implement the Plan until 2027, including the identification of priorities, timelines, financial resources and monitoring activities (Italy’s Ministry of Research 2023).

However, a number of pioneering researchers based at Italy’s universities and research bodies, not only became open science practitioners but, realizing the need for an organized effort, created a number of associations that started educational, research and promotion activities (AISA 2023a; IOSSG 2023; ITRN 2023). In other words, similar to what happened at Italy’s Research Council, where researchers rely on self-determination to outclass a shrinking research budget (Pagliaro and Coccia Reference Pagliaro and Coccia2021), a small group of researchers and librarians self-determined to practise and disseminate the principles and practice of open science, advocating its value within a research community that showed a prolonged lack of interest.

The public discourse on open science in Italy has seen and continues to see important and creative contributions, such as those of Caso (Reference Caso2020), Aliprandi (Reference Aliprandi2017), Giglia (Reference Giglia and Aliprandi2017), Morriello (Reference Morriello2021), Töttössy (Reference Töttössy2018), Gargiulo (Reference Gargiulo2020), Galimberti (Reference Galimberti2017a), Pievatolo (Reference Pievatolo2020b), and many others. Eventually today (mid 2023) Italian researchers may access numerous educational resources on open science. Every year, the aforementioned associations organize meetings in Italy on open science that are not only attended by open science advocates, but also by researchers finally interested in learning how to adopt the principles of open science in their research activities. Much remains to be done in Italy concerning the uptake of open science in education (de Knecht et al. Reference de Knecht, van der Meer, Brinkman, Kluijtmans and Miedema2021), and in evaluation of scholarship (Pagliaro Reference Pagliaro2021; Schimanski and Alperin Reference Schimanski and Alperin2018).

The slow uptake of openness in science in Italy, in conclusion, has several lessons to teach scholars based in other countries where the transition to ‘more open, rigorous and reproducible research’ (Nosek Reference Nosek2021) is also taking place.

First, the case of Italy shows that the adoption of open science can be driven by a small group of pioneering scholars and researchers. In practice, an active minority comprised of scholars and researchers, active in both natural and social and humanistic science, has actively engaged in open science, adopting its practices and disseminating its value. Examples span from chemistry (Ciriminna and Pagliaro Reference Ciriminna and Pagliaro2022a) and law (Caso Reference Caso2020), through the earth (Cocco and Montone Reference Cocco and Montone2022) and life (Anagnostou et al. Reference Anagnostou, Capocasa, Milia, Sanna, Battaggia, Luzi and Destro Bisol2015) sciences, to include virtually all disciplines.

Second, the case of Italy, where for many years no financial resources or personal incentives were actually provided to practitioners of open science, shows that the uptake of open science can take place also in economically developing countries, where financial resources invested in research and education are a small fraction of those available in economically developed countries such as Italy.

Third, universities and science policymakers interested in promoting the adoption of open science should organize practice-oriented educational courses on the principles and tools of open science. The slow uptake of open science practices in Italy, indeed, has also been owing to a prolonged lack of knowledge and awareness amid researchers potentially interested in the shift to opening up their scholarship activity.

Fourth, also in Italy, researchers owning personal academic websites were among the first to use the World Wide Web to openly share the outcomes of their research and educational work with colleagues from across the world and with their students. In other words, the delay of Italy’s researchers to embrace the shift first to OA and then to open science has been partly due also to the limited use of the Web by Italy’s researchers to autonomously disseminate their research and educational work (Ciriminna et al. Reference Ciriminna, Scurria and Pagliaro2023).

As the practice of open science increases, to paraphrase Watson (Reference Watson2015), all publications will be freely and openly accessible, raw data and methods well described and reproducible, software released and peer review reports openly published and no longer anonymous. The objective of open access, indeed, is to maximize research impact by maximizing research access (Harnad Reference Harnad2003), but the objective of open science is to enhance science credibility by improving all steps of the scientific research process, including the final dissemination step. This, inter alia, requires rediscovering intellectual humility in which the limitations of any research work are explicitly presented by the authors and their consequences incorporated into the conclusions (Hoekstra and Vazire Reference Hoekstra and Vazire2021).

Remarkably, the latter study, including five important recommendations on how to practically increase humility in scientific articles (Hoekstra and Vazire Reference Hoekstra and Vazire2021), is self-archived and openly accessible at the repository of the University of Groningen (Hoekstra and Vazire Reference Hoekstra and Vazire2022), whereas single access to the article published in the paywalled journal in which it is currently published (mid 2023) costs $39.95, but it cost $32 when the current study was published in preprint form (Ciriminna and Pagliaro Reference Ciriminna and Pagliaro2022b).

Acknowledgements

This study is dedicated to Subbiah Arunachalam for all he has done to promote and disseminate the principles and tools of open science in India.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

About the Authors

Rosaria Ciriminna is a senior research chemist at Italy’s Research Council. Her research, developed at Palermo’s Institute for nanostructured materials in cooperation with over 20 research groups and institutions based in Italy and abroad, focuses on green chemistry, nanochemistry and the bioeconomy. She has often been cited for excellence in mentoring graduate and undergraduate students.

Mario Pagliaro is a chemistry scholar at Italy’s Research Council where he works as Research Director at Palermo’s Institute for nanostructured materials. His group’s highly collaborative researches focus on nanochemistry, solar energy, and the bioeconomy. In 2008 he co-founded Sicily’s Solar Pole, a research and educational centre through which he jointly pioneered education in solar energy across Sicily. In 2021 he was elected ordinary member of the Academia Europaea.