Despite efforts to improve resources for the identification and investigation of sexual and other forms of abuse in the UK, treatment services for sexually abused children (and their non-abusing parents) remain limited. The evidence base regarding which treatments are most effective, and for whom, is sparse (Reference Finkelhor and BerlinerFinkelhor & Berliner, 1995). It is recognised that childhood sexual abuse is a non-specific risk factor for significant psychopathological disorder in childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Reference Kendall-Tackett, Williams and FinkelhorKendall-Tackett et al, 1993; Reference Bulik, Prescott and KendlerBulik et al, 2001). Several components of the risk factor have been identified including the response of non-abusing parents to disclosure, the degree and quality of support available to the parents and the types of coping strategies employed by the parents (Reference Deblinger, Steer and LipmannDeblinger et al, 1999b ; Reference Everson, Hunter and RunyonEverson et al, 1989). Disclosure can be traumagenic to non-abusing parents (Reference Manion, McIntyre and FirestoneManion et al, 1996; Reference Hiebert-MurphyHiebert-Murphy, 1998) and this in itself can have a negative impact on the child. Clearly it is not possible to alter retrospectively the factors within the abuse itself or those associated with the perpetrator, but by targeting risk factors associated with the response of the non-abusing parent, problems in the child might be reduced. The majority of treatment studies have provided treatment either to the child alone or to both child and parent – usually the mother (Cohen & Mannarino, Reference Cohen and Mannarino1996b , Reference Cohen and Mannarino2000; Deblinger et al, Reference Deblinger, Lippmann and Steer1996, Reference Deblinger, Steer and Lipmann1999a ).

METHOD

Service structure

The Child Sexual Abuse team is a specialist multi-disciplinary team within the Child and Family Mental Health Service in Edinburgh. Referrals are accepted of children up to the age of 14 years (and their non-abusing parents) who may have been traumatised as a result of sexual abuse. The majority of referrals come from general practitioners or from colleagues in Community Child Health, whose remit includes the medical investigation of suspected child abuse. The team receives almost a hundred referrals each year. The service is delivered by three specialist sub-teams.

A team

The A team offers an early intervention service for non-abusing parents of children who have disclosed sexual abuse; this work is the focus of the current pilot research project. The service is provided in a collaborative and supportive framework, and has the following components:

-

(a) empathy and education about child sexual abuse including the grooming process, and education about the possible impact of the abuse on the child;

-

(b) information about the investigative process;

-

(c) assessment of the parents’ and child's pre- and post-disclosure levels of functioning, which includes gaining an understanding of the many factors that might be operating to influence responses (emotional and behavioural) in parents and carers as well as in the child;

-

(d) reinforcement of competent parenting;

-

(e) advice on how to manage current or potential difficulties the child may present.

Based on this information, and on an assessment of the parental response to intervention, a decision is reached – together with parents and carers – regarding whether the child needs to be assessed for possible therapy and hence referred to a therapist in the B team. The experience of the team to date is that approximately half of the children do not require therapy at this stage. Most research has focused on non-abusing mothers, but the early intervention service is offered to both (non-abusing) parents and carers.

B team

The B team offers an assessment and treatment service for children who have been sexually abused and who are suffering significant mental health problems as a result.

C team

The C team offers a consultation service to professionals working with children with sexually inappropriate or sexually abusive behaviour, and an individual assessment and treatment service for the children.

Sample selection

Child sexual abuse was defined as sexual exploitation of a child by another person or persons. The Community Child Health Department of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children in Edinburgh is the central referral point for requests for medical evaluations of children who disclose or are suspected to have experienced sexual abuse. The Department's clinical database was used to identify families eligible for the study from referrals made between 1 January 2001 and 31 October 2001. A total of 115 children were identified from this database. The study included all non-offending carers (male and female) aged 18 years and over of victims of sexual abuse aged under 14 years. Carers under the age of 18 years, non-English speakers, and those who had visual impairment or learning disabilities were excluded, as were children living in residential units. The study was approved by the research ethics sub-committee of Lothian Primary Care NHS Trust.

Recruitment process

For the eligible children, the following information was sought from the database as well as from hospital records: age, gender, date of referral, and the contact details of the social worker who carried out the initial investigation. The identified social work office was then contacted to request information about the suitability of the family for recruitment into the study. The research assistant then approached the carers, explained the study, and sought their agreement to participate.

Procedure during study

The carers were seen at recruitment (baseline), at cessation of contact (post-intervention) and 3 months later (follow-up). At the first contact, information was sought from the carers regarding their age, relationship to child, family composition, education and employment status, health, and previous direct or indirect experience of sexual abuse. On every occasion, measurements were made on both carer and child.

Instruments

Carers

The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Reference Derogatis and SpencerDerogatis & Spencer, 1982) is a 53-item inventory which evaluates psychological symptoms experienced within the previous week. It includes a measure of the overall level of distress, the Global Severity Index (GSI); the pattern of symptoms in nine domains; the Positive Symptom Total (PST) and a further summary measure, the Positive Symptoms Distress Index (PSDI).

The Parent Emotional Reaction Questionnaire (PERQ; Reference Cohen and MannarinoCohen & Mannarino, 1996a ) is a 15-item instrument developed to measure parental emotional reactions (fear, guilt, anger) to the knowledge that their child has been sexually abused. Scores have been found to significantly predict symptoms in sexually abused schoolchildren (Reference Cohen and MannarinoCohen & Mannarino, 1996a ). Internal consistency has been calculated at 0.87, with a 2-week test–retest reliability of 0.90.

Children

Each carer completed the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Reference Achenbach and EdelbrockAchenbach & Edelbrock, 1983). This instrument was developed as a descriptive rating measure to assess both adaptive competencies and behaviour problems for use with carers of children aged 4–18 years. Scores can be calculated for overall behaviour, and for internalising and externalising sub-scales.

Carers also completed the Child Sexual Behavior Inventory (CSBI; Reference Friedrich, Grambsch and DamonFriedrich et al, 1992), which covers 42 items relating to sexual behaviour. The frequency with which the child has shown each behaviour within the previous 6 months (from ‘never’ to ‘at least once a week’) is rated. The CSBI is the only empirical scale that specifically examines sexual behaviour in children. Norms are available from three groups: parents of normal children, parents of psychiatric out-patients and parents of sexually abused children.

Statistical methods

A major aim of the study was to obtain estimates of means, variances and changes in both parent and child scores with a view to designing a randomised, controlled trial of the parental intervention. Further considerations related to interrelationships between the child and parent scores, changes in these, treatment of the children and issues of caseness. The design of the study afforded an opportunity to perform various significance tests of differences between groups at baseline, differences in scores between baseline and post-intervention, relationships between potentially explanatory variables and pre–post differences, and correlational structures. For continuous variables, descriptive statistics presented are means and standard deviations, while t-tests (paired or independent as appropriate) and F tests are used for comparisons between groups. Pearson correlations are reported along with significance levels (P values). For discrete variables frequency tables are presented, but statistical tests are inappropriate because of the small numbers involved.

RESULTS

Children

Demographic data

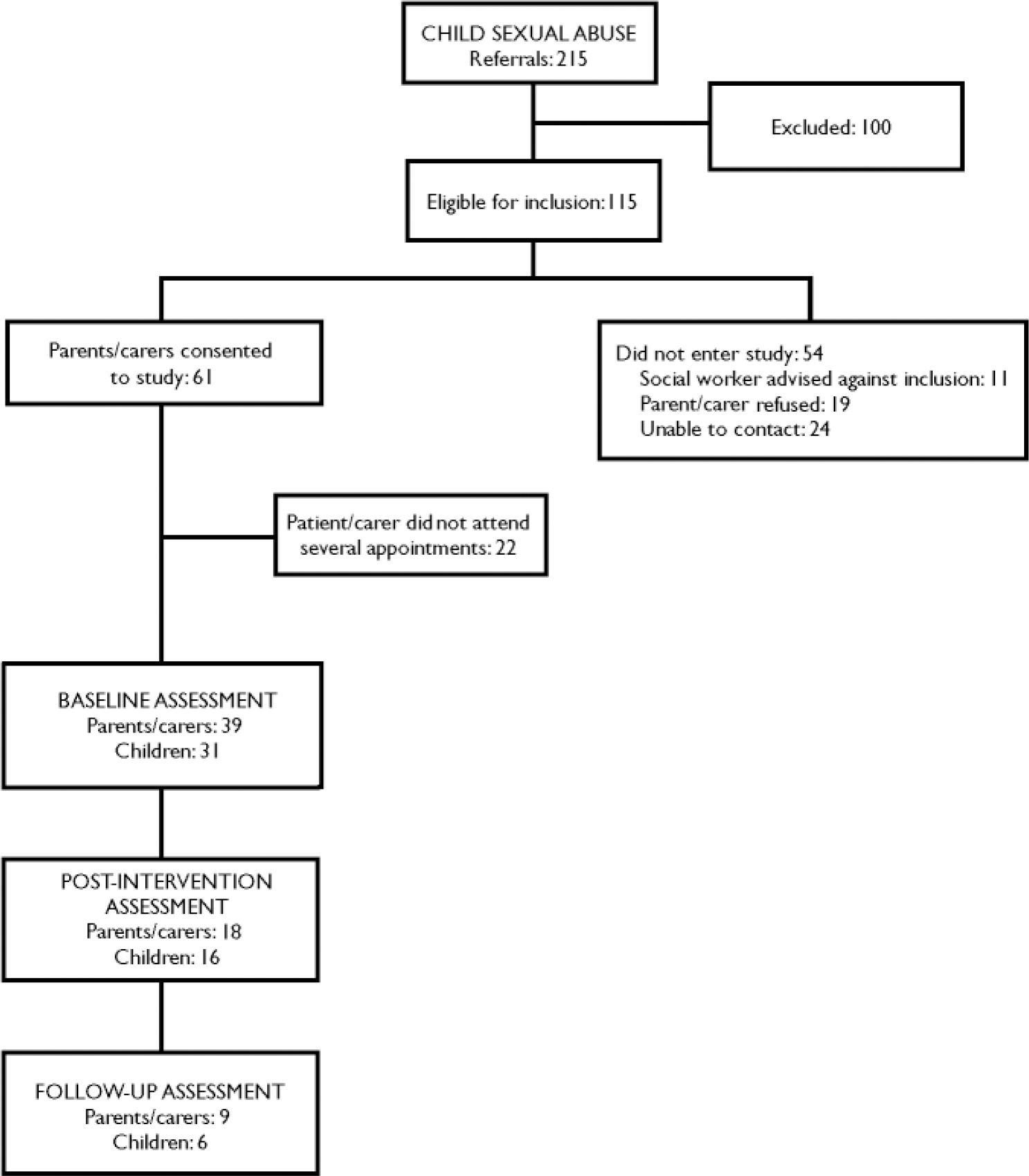

Non-abusing parents or carers of 31 children were recruited to the study. There were 23 girls and 8 boys. The children were aged from 4 to 14 years, with a mean age of 9 (s.d.=2.92). Although children aged 14 years and above would normally be referred to the adolescent mental health service, a referral of one 14-year-old girl with significant developmental delay had been accepted by the team. Most children were referred from the paediatric service (12) or from social work (11); however, 6 were referred by their general practitioner and 2 from psychiatric services (Fig. 1). Two of the children had previously been referred to the Child and Family Mental Health Service in Edinburgh, and 3 to other psychological/psychiatric services. The remaining 26 children had no previous referral. All were of White British or Irish ethnic origin. Ten children were living with both biological parents; one with a parent and step-parent; 17 were living with the mother only; 2 were living with other relatives; and 1 was in the process of being adopted by current carers. Six children were pre-school, 17 were attending primary school and 8 were attending secondary school; 4 were attending non-residential special schools.

Fig. 1 Study profile.

Details of abuse

Sixteen children had suffered sexual abuse from within their own family; only one child had been abused by a stranger. The majority of the abusers were male. Three children were abused by females (this included one child also abused on separate occasions by a male). Four children were abused by two abusers, not necessarily at the same time.

Seven children suffered a single abuse episode; 2 suffered two episodes; 9 were abused over periods of 2–9 months; 13 were abused over periods of 1–7 years.

All 31 children had been touched inappropriately in the genital region; 12 had to engage in masturbatory acts; 5 suffered attempted penetration; 13 suffered vaginal and/or anal penetration (digital and/or with object and/or penile). At least 2 children were photographed in a pornographic fashion. Clearly, several children suffered a range of abusive acts.

Referrals to child assessment and treatment team

Fifteen of the 31 children were referred to the B treatment team.

Parents and carers

Demographic data

Thirty-nine parents and carers were recruited to the study (in the case of nine children, two carers each were recruited, and one carer was associated with two children). Nine were men, 30 women, and all were White, with an age range of 20–49 years. All but four were the biological parent of the child, two being adoptive parents and two other relatives. The modal number of other children at home was one (21 parents). Fourteen of the parents had a history of psychiatric illness.

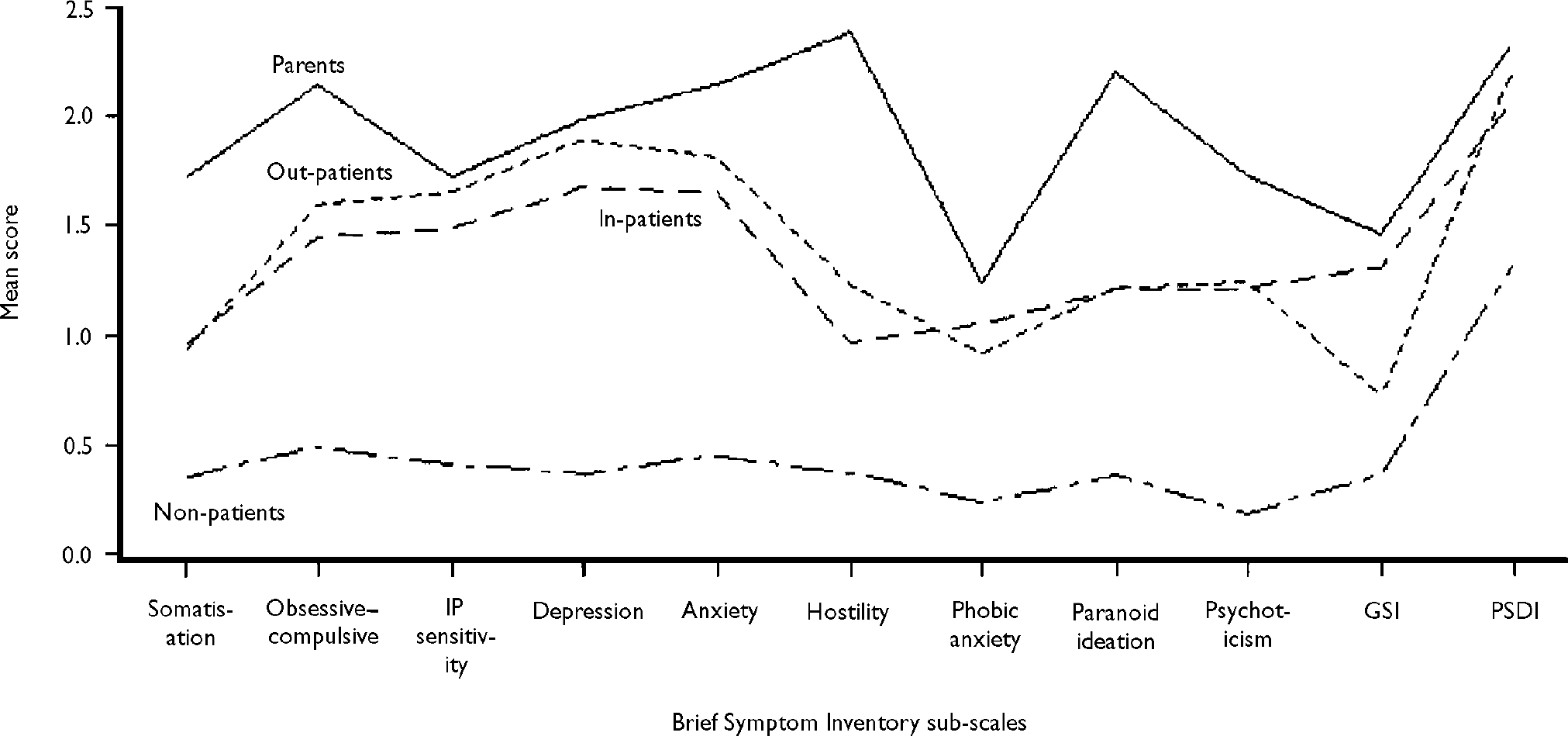

Baseline measures

All parents provided baseline measurements prior to their first appointment with the team. Two children and their parents/carers were not subsequently referred to the team. Figure 2 shows baseline measures on the sub-scales of the Brief Symptom Inventory together with the summary measures GSI and PSDI. Normative data are also plotted for female psychiatric inpatients, out-patients and normal individuals (Reference DerogatisDerogatis, 1993), as the great majority of the parent sample were women (this is a conservative procedure as male norms are in general less than female). The PST is an order of magnitude greater than those plotted in Fig. 2: for the parent group the mean PST was 29.44 compared with norms of 30.35 for in-patients, 31.81 for out-patients and 12.86 for non-patients.

Fig. 2 Baseline scores of parents and carers on the Brief Symptom Inventory sub-scales and summary measures, compared with published norms for psychiatric female in-patients, out-patients and non-patients (Reference DerogatisDerogatis, 1993). IP, interpersonal; GSI, Global Severity Index; PSDI, Positive Symptom Distress Index.

Other baseline comparisons of the measures with published norms are given in Table 1. For variables related to children, both parents’ measures are included at this stage.

Table 1 Baseline comparisons of parental scores with published norms

| Scale | Parental score Mean (s.d.) | Published norms |

|---|---|---|

| Parent Emotional Reaction Questionnaire | 51.62 (13.76) | |

| Child Behavior Checklist1 | ||

| Total | 59.83 (30.07) | Non-referred 52.1 |

| Referred 23.1 | ||

| Internalising sub-scale | 18.77 (12.65) | Non-referred 14.6 |

| Referred 6.3 | ||

| Externalising sub-scale | 18.58 (11.95) | Non-referred 17.5 |

| Referred 8.2 | ||

| Child Sexual Behavior Inventory2 | 6.73 (9.84) | Abused 18.8–9.7 |

| Non-abused 5.1–1.5 |

Caseness at baseline

The scales can be used to provide an operational definition of ‘caseness’ in the parent (BSI) and child (CBCL) respectively. Using the criteria for caseness set out by Derogatis (Reference Derogatis1993), all but one parent would be classified as a case. The one parent not so classified was male and scored zero on all BSI sub-scales except ‘paranoid ideas’ where a score of 1 was registered, about the 65th percentile for normal men. Of the 31 children assessed at baseline, 22 satisfied the caseness criterion of a CBCL score of 50 or over.

Baseline comparisons

Parents

Unbalanced two-way analyses of variance were performed on each of the parent measures, using gender of child, subsequent treatment of child and the interaction as model terms. There was a consistent and (apart from the PERQ score) statistically significant association between subsequent treatment of the child and higher parental scores. Abuse of male children was associated with higher carer scores. Group means are presented in Table 2.

Table 2 Parents’ group scores: related to child's gender and treatment

| Child variable | n | GSI Mean (s.d.) | PST Mean (s.d.) | PSDI Mean (s.d.) | PERQ Mean (s.d.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child's gender | |||||

| Male | 7 | 2.45 (1.01) | 40.29 (13.01) | 3.05 (0.68) | 59.14 (12.02) |

| Female | 32 | 1.24 (0.98) | 27.06 (15.59) | 2.17 (0.69) | 49.97 (13.73) |

| Child's treatment | |||||

| Treated | 18 | 1.86 (1.14) | 34.61 (15.67) | 2.61 (0.76) | 55.67 (14.05) |

| Not treated | 21 | 1.11 (0.91) | 25.00 (14.96) | 2.09 (0.70) | 49.00 (12.83) |

Children

For these comparisons children for whom scores of two carers were available were allocated the mean score of the two values for each variable. Paired t-tests and calculation of correlation coefficients indicate both high correlations and no significant disagreement between the scores of the carers within each pair. Analyses of variance were performed with the above model (child gender and treatment) on the four child-related variables. The only significant associations observed were between subsequent treatment and scores on the CBCL internalising sub-scale and, perhaps predictably, the CBCL total (Table 3). Boys show higher scores than girls on all variables, as indeed do boys in the ‘normal’ population. There is some skewness in the distributions of scores, most notably for the CSBI. Applying distribution-free tests did not alter the conclusions regarding statistical significance. No significant relationship was observed between the children's baseline rating scores and the characteristics of the abuse, the abuser and the duration of the abuse.

Table 3 Children's group scores related to gender and treatment. Significant associations are in bold type

| Child variable | n | Children's score: mean (s.d.) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSBI | CBCL | ||||

| Total | Internalising sub-scale | Externalising sub-scale | |||

| Child's gender | |||||

| Male | 7 | 10.9 (12.9) | 89.0 (37.7) | 26.3 (11.9) | 28.7 (16.3) |

| Female | 24 | 6.3 (9.9) | 56.7 (23.5) | 18.8 (12.7) | 16.8 (9.4) |

| Child's treatment | |||||

| Treated | 15 | 7.4 (10.0) | 80.1 (7.1) | 27.1 (11.5) | 23.2 (13.5) |

| Not treated | 16 | 7.2 (11.5) | 48.8 (24.6) | 14.3 (10.8) | 16.0 (9.80) |

Parent–child correlations

The basic principle of the intervention examined by this research is that child well-being is connected with parental response and well-being. Accordingly, correlations between parent and child variables at baseline and change in scores from baseline to post-intervention were calculated. Table 4 shows that all correlation coefficients are positive as expected, and all except the correlations between CSBI and PST, and between CSBI and PERQ (given in parentheses in Table 4), are statistically significant.

Table 4 Correlation between parents’ and children's scores at baseline assessment (coefficients in parentheses are not statistically significant)

| Scale | GSI | PST | PSDI | PERQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | ||||

| Total | 0.76 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.48 |

| Internalising | 0.60 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 0.43 |

| Externalising | 0.58 | 0.47 | 0.60 | 0.38 |

| CSBI | 0.36 | (0.29) | 0.38 | (0.22) |

Changes in scores

Changes from baseline to post-intervention assessment were examined for all scores and also for child's ‘caseness’. The mean time between the relevant interviews was 5.5 months (s.d.=2.4) and the maximum and minimum gaps were 9 months and 10 weeks, respectively.

Parents

Altogether 18 sets of pre- and post-intervention parental scores were available, relating to 16 children (as mentioned above, one parent was responsible for two children, and two carers were recruited in the case of three other children). Paired t-tests were conducted on GSI, PST, PSDI and PERQ scores (Table 5). None of these changes was statistically significant, but apart from the PST score all showed a reduction in parental distress.

Table 5 Changes in parents’ scores before and after the intervention

| Scale | Baseline score Mean | Post-intervention score Mean | Difference Mean (s.d.) | t (d.f.=17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSI | 1.492 | 1.299 | 0.193 (0.733) | 1.12 |

| PST | 31.94 | 32.61 | –0.67 (11.16) | –0.25 |

| PSDI | 2.230 | 1.965 | 0.265 (0.589) | 1.91 |

| PERQ | 55.61 | 52.28 | 3.33 (11.42) | 1.24 |

Children

Data for 16 children were available pre- and post-intervention. When a child was scored by two carers the average of the two scores was taken. Eight of the 16 children were treated by the B team. All the treated children satisfied the CBCL caseness criterion at baseline, as did five of the eight untreated children. Post-intervention changes were towards non-caseness. Two of the treated children and two of the children who did not receive direct treatment achieved non-case scores.

Table 6 gives means and paired t-tests of differences on the four measures employed comparing baseline with post-intervention. The signs of mean changes indicate improvement on all variables, but statistical significance is only achieved for the score on the CSBI.

Table 6 Changes in children's scores following the intervention (statistically significant values are given in bold type)

| Scale | Baseline score Mean | Post-intervention score Mean | Difference Mean (s.d.) | t (d.f.=17) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | ||||

| Total | 67.31 | 59.06 | 5.25 (22.10) | 1.49 |

| Internalising | 22.69 | 19.44 | 3.25 (7.79) | 1.67 |

| Externalising | 21.50 | 20.50 | 1.00 (10.46) | 0.38 |

| CSBI | 7.38 | 4.94 | 2.44 (4.03) | 2.42 |

Table 7 displays correlations between change scores for children and parents. Changes in scores on the CSBI do not correlate with parental score changes, but CBCL scores do. Despite the small numbers two of the correlation coefficients were statistically significant, and several of the others approached statistical significance.

Table 7 Parent–child correlations of changes (statistically significant values are given in bold type)

| GSI | PST | PSDI | PERQ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBCL | ||||

| Total | 0.43 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.46 |

| Internalising | 0.41 | 0.52 | 0.31 | 0.68 |

| Externalising | 0.25 | 0.12 | 0.25 | 0.08 |

| CSBI | 0.02 | 0.09 | –0.07 | 0.20 |

Follow-up

Follow-up information was obtained for nine parents of six children approximately 3 months after the end of the intervention. There was no evidence of deterioration in either children or parents.

DISCUSSION

Main findings

The study found a high prevalence rate of psychopathological symptoms in the non-abusing parents and their children in the period following disclosure of sexual abuse. All but one of the 39 parents at baseline satisfied criteria for caseness as operationally defined by the BSI. Twenty-two of the 31 children satisfied caseness criteria for the CBCL. These findings are in keeping with previous studies which have highlighted the traumagenic effect on parents of the discovery that their child has been abused. It is likely that the psychopathological symptoms reported were in part a result of the discovery of abuse and subsequent events, such as the investigative process, a breakdown in trust and relationship with the abuser, and family disruption.

Following treatment intervention by the team, there was a reduction in parental distress and degree of psychopathology. Numbers were too small to reach statistical significance and there was no control group. Despite this, it is unlikely that the parental distress – which in all but one had reached clinically significant levels – would have resolved spontaneously. This aspect will be addressed directly in the proposed randomised, controlled trial.

The team's clinicians correctly identified those children most likely to need treatment. Part of the treatment intervention for parents involves helping them support and empathise with their child and reaffirming previous healthy parenting skills. It also includes discussion of any emotional or behavioural problems in the child and whether or not these can be addressed solely by the parents. If this is not possible – the child's difficulties are too severe, or the parents are continuing to have significant problems in coping – it is agreed that the child will be assessed for possible therapy. In the research group, 16 of the children were not referred for assessment – the clinicians, in collaboration with the parents, deemed this unnecessary. Fifteen of the children did go on to be assessed and receive therapy. Analysis of the baseline scores of the parents and children in this group revealed them to be much higher than in the non-referred group.

Implications for subsequent trial design

An important aim of this research was to obtain information to help design a randomised, controlled trial of the parental intervention. The results indicate that reductions occur in scores on all scales for parents, but although the baseline scores for almost all parents are in ranges similar to those of psychiatric patients, the well-being of the child is a key aim of the intervention. Accordingly, we considered power calculations relating both to parents and children. The correlational and change results suggest that the PERQ score may be variable in practice, and although it has been used elsewhere no published norms appear to be available. The correlation of change in PERQ with change in CBCL internalising score indicates that it should be retained as a secondary outcome. Of the BSI scores the PST does not take severity into account, while the GSI is recommended for use as part of the caseness criterion. Accordingly, GSI is a suitable primary outcome measure for parents.

Scores on the CSBI were only slightly higher than normal values at baseline. Despite the large t value for change in CSBI, we feel that two conclusions follow: first, that it is not appropriate to use CSBI as a primary outcome, and second, that our analysis might not be applicable to a population of abused children with high CSBI scores.

Correlations between parent and child changes in scores suggest that we should restrict attention to the CBCL total score and the CBCL internalising score as primary outcomes for the children (further details available from the authors upon request.)

Clinical Implications and Limitations

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS

-

▪ This study confirms the high levels of psychopathological symptoms in parents of children who disclose sexual abuse (as well as in the children themselves) and the need for readily accessible treatment interventions.

-

▪ The parental intervention appears to have benefited both the parents and their children.

-

▪ Clinical judgements about which children in this study required further intervention appeared to be correct.

LIMITATIONS

-

▪ This is not intended to be a controlled trial and results should not be over-interpreted – in particular, the small numbers of parents and children recruited means that changes in scores have to be very large to achieve statistical significance.

-

▪ There was no independent assessment of the child other than parental scoring of the two child-related questionnaires.

-

▪ The high percentage of non-cooperation may indicate a selection bias in recruitment.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all members of the child sexual abuse team whose commitment to their clinical work and to this research has been unremitting. Thanks also to the parents and carers who participated in the study during what must have been one of the most difficult periods of their lives. We wish them and their children happier and safer times ahead.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.