1. Introduction

Corporate entrepreneurship (CE) is the means by which organizations grow and attain positive performance outcomes (Kuratko, Reference Kuratko2007; Zahra & Covin, Reference Zahra and Covin1995). Prior research has investigated certain firm characteristics and their relationship to CE such as managerial support (Hornsby, Kuratko, Shepherd, & Bott, Reference Hornsby, Kuratko, Shepherd and Bott2009), organizational structures (Chebbi, Yahiaoui, Sellami, Papasolomou, & Melanthiou, Reference Chebbi, Yahiaoui, Sellami, Papasolomou and Melanthiou2020; Chowhan, Pries, & Mann, Reference Chowhan, Pries and Mann2017) culture (Chandler, Keller, & Lyon, Reference Chandler, Keller and Lyon2000; Kanter, Reference Kanter1985), and incentive systems (Cabral, Francis, & Kumar, Reference Cabral, Francis and Kumar2020; Sathe, Reference Sathe1989).

While these organizational features are important to the attainment of firms' entrepreneurial goals, without available physical resources (slack resources), CE is difficult to undertake. (Filatotchev & Piesse, Reference Filatotchev and Piesse2009; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005; Zahra, Reference Zahra1996). Hence, many studies examine how organizational factors work alongside slack resources in facilitating CE (Cheng & Kesner, Reference Cheng and Kesner1997; Patzelt, Shepherd, Deeds, & Bradley, Reference Patzelt, Shepherd, Deeds and Bradley2008; Simsek, Veiga, & Lubatkin, Reference Simsek, Veiga and Lubatkin2007; Zahra, Hayton, & Salvato, Reference Zahra, Hayton and Salvato2004). The general belief is that the presence of slack resources should encourage organizations to take on risks and increase CE activities since such risk-taking activities should have a positive impact on firm performance (Ciftci & Cready, Reference Ciftci and Cready2011; Hornsby, Kuratko, & Zahra, Reference Hornsby, Kuratko and Zahra2002; Sougiannis, Reference Sougiannis1994).

However, slack's influence on CE, particularly R&D spending, (a key input to the pursuit of CE activities for many industries), has not always been found to be linear and positive (Bond, Harhoff, & Van Reenen, Reference Bond, Harhoff and Van Reenen2005; Bradley, Wiklund, & Shepherd, Reference Bradley, Wiklund and Shepherd2011; Filatotchev & Piesse, Reference Filatotchev and Piesse2009; Hao & Jaffe, Reference Hao and Jaffe1993; Lee & Wu, Reference Lee and Wu2016). For instance, instead of using slack for risky activities, organizations may choose to use slack as a buffer against future uncertainties or potential losses. As such, while the role of slack in CE is viewed as an important factor that determines the extent to which firms engage in CE, the direction and strength of its impact appear contextual.

In an attempt to add clarity to this ambiguity, we turn to an emerging theme in CE literature - the entrepreneurial mindset of organizational members (Garrett & Holland, Reference Garrett and Holland2015; Garrett, Mattingly, Hornsby, & Aghaey, Reference Garrett, Mattingly, Hornsby and Aghaey2020; Ireland, Covin, & Kuratko, Reference Ireland, Covin and Kuratko2009; Kuratko, Hornsby, & McKelvie, Reference Kuratko, Hornsby and McKelvie2021). This literature suggests that understanding not only the external business environment but also the psyche of corporate actors can help explain how organizational members make decisions given certain judgments, assessments, and beliefs about both the past and the future of the firm (Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse, & Smith, Reference Mitchell, Busenitz, Lant, McDougall, Morse and Smith2002). Given the natural impact managerial cognition has on corporate decision making, we link managerial attribution to the stream of research addressing slack resources and CE in order to further understand how managerial mindsets influence whether firms view available resources as a means of insulating against risk or engaging in it. Specifically, we look at how organizational leaders' attribution of past performance moderates the relationship between slack and firms' pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities via R&D. We argue that managerial attributions are a reflection of organizational cognitions, and that the literature's finding of inconsistencies in the use of slack for CE can be explained by how managers attribute past performance.

Attribution refers to the way in which individuals explain the causes for an event (Heider, Reference Heider1958), whereas attribution theory is concerned with how different types of attributions influence motivation and future behavior (Kelley & Michela, Reference Kelley and Michela1980). Work conducted under the rubric of ‘managerial attribution’ examines the effects of managerial attribution on subsequent behavior. For instance, several studies have tried to explain the link between a top management team's attribution and firm performance (Bettman & Weitz, Reference Bettman and Weitz1983; Clapham & Schwenk, Reference Clapham and Schwenk1991; Salancik & Meindl, Reference Salancik and Meindl1984) and financial policies or forecasts (Li, Reference Li2010a; Libby & Rennekamp, Reference Libby and Rennekamp2012). More specifically within the field of entrepreneurship, attribution theory has been used to explore how attribution style affects new venture formation (Parker, Reference Parker2009; Tang, Tang, & Lohrke, Reference Tang, Tang and Lohrke2008), entrepreneurial success (Diochon, Menzies, & Gasse, Reference Diochon, Menzies and Gasse2007), hindsight biases by entrepreneurs (Cassar & Craig, Reference Cassar and Craig2009) and entrepreneurial failure and exit (Cardon, Stevens, & Potter, Reference Cardon, Stevens and Potter2011; Mantere, Aula, Schildt, & Vaara, Reference Mantere, Aula, Schildt and Vaara2013; Ucbasaran, Westhead, Wright, & Flores, Reference Ucbasaran, Westhead, Wright and Flores2010). The findings across these papers are largely consistent with what Mueller and Thomas (Reference Mueller and Thomas2001: 56) suggest: ‘if one does not believe that the outcome of a business venture will be influenced by personal effort, then that individual is unlikely to risk exposure to the high penalties of failure.’ Thus, we suggest that organizations are motivated to invest in CE when organizational leaders believe that their firms' performance is influenced by efforts undertaken by the firm.

By looking at managerial attributions, we provide a cognitive interpretation of a firm's reference point in decision making. Others have examined the firm's propensity to engage in CE by looking at a firm's performance aspiration or its performance above or below a reference point (Chen, Reference Chen2008; Greve, Reference Greve2003). Their findings are oftentimes explained by prospect theory and behavioral theory of the firm, wherein risk-taking decisions by managers are examined in relation to their performance aspirations, such as prior performance or mean industry performance. However, several authors have questioned the suitability of using such reference points or aspiration levels of performance. As Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb, and McGuire (Reference Holmes, Bromiley, Devers, Holcomb and McGuire2011) suggests, different firms may use different reference points for performance criteria. In particular, the ‘differences in decision frames and heuristics give rise to ‘variable rationality’ among and within players over time’ (Amit & Schoemaker, Reference Amit and Schoemaker1993: 42). Thus, a cognitive approach to understanding organizational rationale in decision making would be more appropriate (Osiyevskyy & Dewald, Reference Osiyevskyy and Dewald2015). By looking at how top management makes sense of their own role (internal attribution) in firm performance, we link managerial attributions to organizational decision-making on CE.

Thus, our study makes three contributions to the literature. First, we examine the role of top management cognition on entrepreneurial behavior and argue that managerial attribution is a key factor in understanding how slack resources and CE interrelate. That is, we find that a firm's use of slack resources varies with managerial attribution of past performance and offers a new lens by which researchers can explore how slack resources impact future firm behavior and willingness to undertake CE. These findings also help explain why the relationship between slack and CE found in prior literature is not always linear (Geiger & Cashen, Reference Geiger and Cashen2002; Geiger & Makri, Reference Geiger and Makri2006). Second, we identify a distinct aspect of managerial cognition which helps explain why firms have different CE strategies even when all else remains the same. We believe that this helps to address the inconsistent findings in the literature whereby some firms reduce subsequent CE efforts following poor performance while others increase CE efforts (Bolton, Reference Bolton1993; Bougheas, Görg, & Strobl, Reference Bougheas, Görg and Strobl2003; Gentry & Shen, Reference Gentry and Shen2013). Third, contrary to the suggestions of prospect theory, we find that a firm's risk-seeking is not necessarily based on its performance being above or below a neutral reference point. Rather, we suggest it is influenced by the attributions that are linked to this performance. Firms do not always become risk-averse and shy away from CE when there is good performance, nor do firms always become risk-seeking and increase CE efforts when there is poor performance. Instead, decisions in the firm are made based on management's beliefs as to why these past outcomes came about. Overall, we add a new element to the discussion of decision-making under risk, especially with consideration to the use of slack resources.

2. Theory development and hypotheses

Firms need slack resources to engage in CE activities, such as R&D and innovation (Damanpour & Aravind, Reference Damanpour, Aravind, Hage and Meeus2006; Garrett et al., Reference Garrett, Mattingly, Hornsby and Aghaey2020; Richtnér, Åhlström, & Goffin, Reference Richtnér, Åhlström and Goffin2014). Slack resources provide firms with flexibility inasmuch as these resources can be deployed to achieve organizational goals (George, Reference George2005). Additionally, when firms have more slack it provides them a buffer against negative shocks should their entrepreneurial endeavors not prove fruitful. In contrast, when firms have little slack, they have limited ability to take risks and be experimental (Alessandri & Pattit, Reference Alessandri and Pattit2014; Nohria & Gulati, Reference Nohria and Gulati1996) and failed undertakings can lead to more drastic financial consequences. However, studies show that the relationship between slack and CE is not always as straightforward as theory would suggest and there are situations where firms with greater slack are not engaging in more CE (Geiger & Cashen, Reference Geiger and Cashen2002; Geiger & Makri, Reference Geiger and Makri2006). To explain this inconsistency, some studies have turned to firm performance and environmental risks as potential moderators of the slack-CE relationship (e.g., Simsek, Veiga, and Lubatkin, Reference Simsek, Veiga and Lubatkin2007).

Within this stream, there is research which examines the slack-CE relationship by exploring how firms respond to outcomes when benchmarked against industry averages or a firm's own past performance (Chen, Reference Chen2008; Greve, Reference Greve2003). The basic idea behind this line of research is that considering a firms' aspirations/reference performance and realized performance can tell us which firms are satisfied with their current performance and which firms are underperforming relative to aspirations. Thus, it distinguishes between firms that are not looking to deploy more resources for growth from those that are motivated to engage in more CE through the use of slack. However, such a determination of aspirations and performance references are not necessarily consistent with top management thinking. Industry averages may not be an appropriate benchmark given the sizeable differences that exist between firms within an industry, while the historical performance of the firm does not consider the continually changing operating and competitive landscape of the business environment. Further, studies based on this view offer little consideration as to whether the success or failure to hit these targets was due to firm efforts or to external environmental factors which should influence a firm's likelihood to engage in future activities.

Instead, firms' own discussions regarding performance benchmarks and their attributions of the causes of performance can potentially shed new light on the influence of slack on CE. While attribution theory was originally used to understand how an individual's explanation for the causes of an event have consequences for their affect and behavior (Kelley & Michela, Reference Kelley and Michela1980), attribution theory's focus ‘on how people's interpretation of outcomes influences their propensity to persist with a course of action’ (McGrath, Reference McGrath, Pettigrew, Thomas and Whittington2002: 305), makes the theory well-suited for explaining entrepreneurial activities. Thus, it has been used in research to understand how decision makers' attributions affect entrepreneurial intentions, persistence with start-up activities, strategic reorientation, and entrepreneurial failure (Barker & Barr, Reference Barker and Barr2002; Bonnett & Furnham, Reference Bonnett and Furnham1991; Cardon, Stevens, & Potter, Reference Cardon, Stevens and Potter2011; Gatewood, Shaver, & Gartner, Reference Gatewood, Shaver and Gartner1995; Mantere et al., Reference Mantere, Aula, Schildt and Vaara2013; Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2015), as well as to examine the attributional styles that characterize entrepreneurs (Ahmed, Reference Ahmed1985; Kaufmann, Welsh, & Bushmarin, Reference Kaufmann, Welsh and Bushmarin1995; Parker, Reference Parker2009).

In a similar vein, we examine top management's attributions of firm performance since it is reflective of decision makers' cognitive and motivational orientations (Ford, Reference Ford1985). Firms, through their strategic decision makers, seek feedback on organizational actions. They scan organizational events and engage in the interpretation process ‘of translating these events, of developing models of understanding, of bringing out meaning, and of assembling conceptual schemes among key managers,’ (Daft & Weick, Reference Daft and Weick1984: 286). This process results in the development of similar cognitive schemes among organizational members, especially the top management, and in turn leads to convergence in individual interpretations. In particular, the interpretation of firm performance leads to the development of a well-entrenched organizational cognitive schema that becomes the basis for resource allocation decisions within the firm (Nottenburg & Fedor, Reference Nottenburg and Fedor1983) which impacts subsequent organizational outcomes (Lehmberg & Tangpong, Reference Lehmberg and Tangpong2020).

To that end, we focus on managerial attributions made with respect to the internal and external causes of performance to examine how the use of slack for CE is altered. This distinction between the two attributions is important because while internal attributions reflect top management's perspectives on how factors which are within their control affect firm performance, external attributions reflect top management's perception of how external factors, such as market and macroeconomic conditions, relate to firm performance. Additionally, it is important to distinguish between positive and negative attributions. This is because the impact of internal (or external) attributions on subsequent decision-making depends on whether managers think internal (or external) factors played a favorable or unfavorable role in achieving desired performance outcomes for the firm. Thus, if a manager makes an internal (or external) attribution for a favorable outcome, it is an instance of a positive internal (or external) attribution, whereas if a manager makes an internal (or external) attribution for an unfavorable outcome, it is a negative internal (or external) attribution.

Below, we discuss attributions in greater depth, followed by how internal and external attributions affect the relationship between slack and CE. We use Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009) discussion on attributions and resultant motivational states as the starting point for understanding the impact of positive internal attributions, negative internal attributions, positive external attributions and negative external attributions. The relationship between attribution and CE is then fleshed out based on the broader literature linking attribution to entrepreneurial and corporate behavior. We then develop our theoretical predictions related to each type of attribution. To do this, in our hypotheses we look at whether managers consider the impact of internal factors and external factors on firm performance in a predominantly positive or negative light, in relation to each other. This allows us to examine how management's overall orientation regarding attributions affects their use of slack for CE, rather than a simple count of one type of attribution.

2.1 The role of internal attributions

Attribution happens when people identify the causes for an event or outcome. Attribution theory suggests that the way people attribute the causes for a positive or negative outcome can affect their mood and motivation and in turn affect their behavior. For instance, Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009) suggest that internal attributions for positive outcomes are associated with the motivational states of empowerment and resilience that allow individuals to exert more effort and be more adaptable. Similarly, Weiner and Kukla (Reference Weiner and Kukla1970) find that making more internal attributions for success results in high achievement motivation. On the other hand, internal attribution for negative outcomes leads to helplessness and dysfunctional consequences (Riolli & Sommer, Reference Riolli and Sommer2010). Williams, Thorgren, and Lindh (Reference Williams, Thorgren and Lindh2020) find that entrepreneurial reentry was unlikely for those who initially made internal attributions for failure. In this vein, studies in organizational attribution have proposed that organizational members who repeatedly attribute negative outcomes internally are likely to feel unmotivated and adopt a helpless attitude (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009; Martinko & Gardner, Reference Martinko and Gardner1987).

The link between attributions and motivational states have led researchers to examine entrepreneurial behavior and risk-taking through the lens of attribution theory. For instance, several studies suggest that entrepreneurs and individuals with entrepreneurial intentions have greater internal loci of control (Bonnett & Furnham, Reference Bonnett and Furnham1991; Kaufmann, Welsh, & Bushmarin, Reference Kaufmann, Welsh and Bushmarin1995) and attribute positive outcomes to personal effort and abilities (Baron, Reference Baron1998). Gartner, Shaver, and Liao (Reference Gartner, Shaver and Liao2008) find that, while entrepreneurs believe opportunities exist in the environment, they also believe that opportunities are identified and acted upon successfully due to their own efforts. In this vein, Trevelyan (Reference Trevelyan2011) finds that entrepreneurs who have confidence in their own abilities are more likely to exert efforts toward new venture development. Furthermore, those who make more positive internal attributions are also more likely to take risks because such attributions lead to greater perceived certainty about the outcomes of one's actions. For instance, Tang, Tang, and Lohrke (Reference Tang, Tang and Lohrke2008) find that risk-taking propensity and need for achievement are significantly higher for nascent entrepreneurs who make internal attributions for their success. Simon and Houghton (Reference Simon and Houghton2003) show that overconfidence, usually marked by excessive positive internal attribution, results in the introduction of risky products.

On the flip side, a strong presence of negative internal attributions can make decision makers feel more accountable for their actions and make them sensitive to decisions that have the slightest chance of going awry. This can inhibit their ability to take bold decisions and encourage risk aversion (Kahneman & Lovallo, Reference Kahneman and Lovallo1993). Hence, entrepreneurial behavior is associated with a more positive - rather than a more negative - belief in ones' abilities and efforts. Based on the above discussion we propose that slack will result in more (less) CE for firms that make more internal attributions to positive (negative) outcomes. Thus, we put forth:

Hypothesis 1: CE increases as slack increases for firms that make relatively more internal attributions to positive, rather than negative firm performance.

2.2 The moderating role of external attributions

Unlike internal attributions, the effect of external attributions on motivation, particularly when these attributions are identified causally with negative outcomes, is more nuanced. Negative external attributions allow people to protect their self-esteem by deflecting blame and/or viewing external factors as hostile (Blaine & Crocker, Reference Blaine, Crocker and Baumeister1993; Gudjonsson & Singh, Reference Gudjonsson and Singh1989; Weiner, Russell, & Lerman, Reference Weiner, Russell and Lerman1979). Thus, negative external attributions are linked to motivational states that induce greater effort, be it for better, as in the case of an empowered motivational state, or worse, as in the case of an aggressive motivational state (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009). This is also consistent with Williams, Thorgren, and Lindh (Reference Williams, Thorgren and Lindh2020) finding that entrepreneurial reentry is most likely when the initial attributional tendency following a failed business is toward external attributions.

First, in line with empowerment motivation, when decision makers perceive difficulties in the external environment, they may turn to more internal efforts to overcome these difficulties. For instance, Salancik and Meindl (Reference Salancik and Meindl1984) find that when a firm's top management make negative external attributions, they then take corporate action that indicates that steps are being taken to deal with the negative environment. Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009) suggest the empowerment effect of negative external attributions comes about because organizational actors feel hopeful about their chances of recovering from a setback when its cause is attributed to external factors.

Second, in line with aggression motivation (Keashly & Neuman, Reference Keashly and Neuman2008; Lee, Brotheridge, Brees, Mackey, & Martinko, Reference Lee, Brotheridge, Brees, Mackey and Martinko2013), when organizational actors perceive the external environment as hostile, they may retaliate to the frustration of what they perceive as an unfair situation with internal efforts that verge on recklessness. For instance, David, Bloom, and Hillman (Reference David, Bloom and Hillman2007) suggest that managers do not like their authority to be challenged by external factors and in reaction, would try to exert more control over firm's strategic decisions. Similarly, Ford (Reference Ford1985) suggests that external attributions for poor performance can lead to reactance, wherein restrictions in the freedom to engage in a certain behavior further motivate engagement in such behavior. The notion of over-investment following negative external attributions is consistent with the literature on an escalation of commitment. Escalation of commitment occurs when individuals perceive a negative outcome as being caused by an external event, and thus feel the need to prove that they were right in their prior action by escalating their commitment to such a course of action (Staw, Reference Staw1976, Reference Staw1981). For instance, Lai (Reference Lai1994) examines the role of external attributions during the Norwegian banking crisis and suggests that when managers make negative external attributions, they engage in an escalation of commitment and display an inability to engage in appropriate strategic change. Thus, in line with empowerment and aggression motivational states, we propose that firms that make more external attributions to negative outcomes will engage in more risk-seeking behavior. Hence, external attributions moderate the relationship between slack and CE. Specifically, we put forth:

Hypothesis 2: CE increases as slack increases for firms that make relatively more external attributions to negative, rather than positive firm performance.

According to Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009), when positive external attributions are made alongside negative internal attributions, it results in the motivational state of learned helplessness, which in turn implies inaction on the part of the organizational actors. This pessimistic attribution style, essentially attributes success to luck and failure to personal ability. Thus, this combination of attributions makes good outcomes seem unobtainable because of a perceived effort-reward disconnect. This lack of any specific expectation for success increases the likelihood of motivational disturbances such as depression and procrastination and inhibits learning (Locke & Latham, Reference Locke and Latham2004). In particular, decision-makers come to see themselves as ineffectual in facilitating desired outcomes for the firm, possibly due to a history of failures (Chung, Choi, & Du, Reference Chung, Choi and Du2017; Ford, Reference Ford1985) or limited power to enact their decisions, and come to view any success as a result of factors which are beyond their control. Consequently, managers may withhold taking proactive decisions when confronted with stressful situations. For instance, Renaud, Narkier, and Bot (Reference Renaud, Narkier and Bot2013) suggest that the learned helplessness of firm executives prevents the implementation of innovative business-driven practices in large firms. In a similar vein, Wunderley, Reddy, and Dember (Reference Wunderley, Reddy and Dember1998) find that business leaders' pessimism is negatively related to their innovative proclivities. In such a situation, instead of taking charge and trying to direct firm efforts in a meaningful fashion, decision-makers step back so that they are not held responsible for further failures.

On the other hand, Harvey and Martinko (Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009) suggest that resilience or persistence of meaningful effort is possible when neither external nor internal factors are overly favored over the other for success. Even when external factors are viewed favorably, persisting at goal-directed behavior requires the belief that personal effort will triumph over adversity (Krueger, Reference Krueger, Acs and Audretsch2003; Seligman, Reference Seligman1990). Thus, if positive internal causes are acknowledged alongside positive external causes, firms won't be risk-averse.

In line with the motivational state of learned helplessness and resilience, we propose that firms that make positive external attributions in the presence of negative internal attributions will be risk-averse, compared to those that make positive external attributions in the presence of positive internal attributions. Hence, external attributions moderate the relationship between internal attribution, slack and CE. Specifically, we put forth:

Hypothesis 3: CE decreases as slack increases for firms that make relatively more external attributions to positive firm performance and internal attributions to negative firm performance.

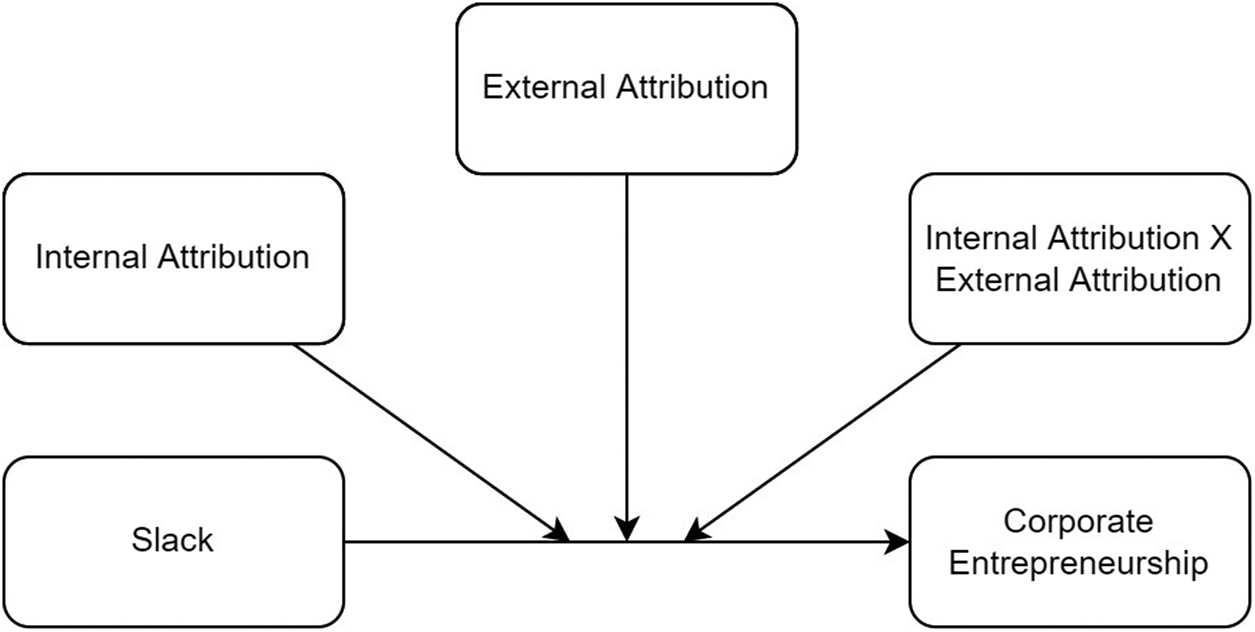

Figure 1 illustrates the theoretical model for our hypotheses.

Figure 1. The Moderating Effect of Managerial Attribution on the Relationship between Slack and CE.

3. Methods

3.1 Context & sample

Our data set consists of all publicly traded firms in the pharmaceutical industry (SIC code 2384) in 2005 and 2006 in the United States for which relevant data were available. Firms in the pharmaceutical industry are involved in the manufacturing, fabricating, or processing of pharmaceutical drugs (www.osha.gov) and are crucially dependent on research and development activities for their success. Focusing on one industry allows us to remove unexplained variance in a limited time period, such as that of industry effects on performance, overall market trends, and changes in legislation. Furthermore, this allows us to better focus on the variation in the perception of the environment as a function of managerial cognition rather than as a function of the actual changes in the environment.

We use publicly available data to capture slack and our operationalization of CE, which is research and development (R&D) spending. R&D spending is a vital input to entrepreneurial activities in the pharmaceutical industry (Dunlap-Hinkler, Kotabe, & Mudambi, Reference Dunlap-Hinkler, Kotabe and Mudambi2010; Pavitt, Reference Pavitt1984) that relies on such spending to drive new product development. Furthermore, high failure rates and consequent volatility in the R&D throughput makes the maintenance of a steady innovation pipeline and managerial decisions on investments into R&D even more important for pharmaceutical firms (Nightingale, Reference Nightingale2000). Thus, the pharmaceutical industry is one of the most R&D intensive industries in the United States (Moncada-Paternò-Castello, Ciupagea, Smith, Tübke, & Tubbs, Reference Moncada-Paternò-Castello, Ciupagea, Smith, Tübke and Tubbs2010). For each company, we use a lagged research model in which we assess how managerial attribution moderates the effect of slack on R&D spending in the subsequent year.

Prior research has examined publicly available qualitative documents such as Management's Discussion and Analysis (MD&A), letters to shareholders, and management forecasts as meaningful sources of managerial attributions for firm-level performance (Baginski, Hassell, & Kimbrough, Reference Baginski, Hassell and Kimbrough2004; Barker & Barr, Reference Barker and Barr2002; Barr, Stimpert, & Huff, Reference Barr, Stimpert and Huff1992; Clapham & Schwenk, Reference Clapham and Schwenk1991; Li, Reference Li2010a). In this vein, we perform content analysis on the MD&A section of the 10-K filings to identify the type of attributions that are made by each company (Short, Payne, Brigham, Lumpkin, & Broberg, Reference Short, Payne, Brigham, Lumpkin and Broberg2009). The use of MD&A sections of firm reports allows for a relatively uniform method for coding managerial attributions. Furthermore, MD&As are closely linked to top management thinking since the narrative provides an interpretation by the management of changes in firm performance (Carton & Hofer, Reference Carton and Hofer2010; Li, Reference Li2010b). We code attribution based on the definition by Bettman and Weitz (Reference Bettman and Weitz1983): attribution involves an instance of causal reasoning, where an attribute is linked to any performance outcome. This performance outcome includes sales, profits, income. We identify internal attribution factors (i.e., those related to the company) and several types of external attribution factors (i.e., those related to the company's external environment).

Coding requires a clear indication of cause and effect. We considered positive and negative effects on sales, profit and income. We did not make an attributional coding when the direction of effect was unclear. That is, we needed a clear indication as to whether the external or internal factor improved or worsened (increased/decreased, strengthened/weakened) the outcome. Also, coding only pertained to attributions made for results in the current year. Forward-looking statements or discussion of performance in previous years were not considered. Since we undertook manual coding, attribution was assessed not just at the sentence level but across paragraphs as well.

Attributions which related to firm-specific factors were coded as internal. Thus, internal attribution was made when performance was positively or negatively affected by firm-level decisions such as specific products launched by the firm, a particular division of the firm, research or administrative expenses, operational efficiency, advertising, or marketing. Attributions which related to factors not directly under the control of the firm, such as regulatory changes, competitor actions, macroeconomic changes, or unforeseen circumstances were coded as external. Thus, we have four-count measures where we count the number of positive internal, negative internal, positive external, and negative external attributions. The following table illustrates individual instances of each type of attribution (Table 1).

Table 1. Examples of attribution types

For further clarity on how each attribution was coded, we have reproduced the coding schemes from A for Author. (2017) in Appendix 1. In order to increase the validity of the attribution measures, we used two individual coders of the managerial attributions in the MD&A sections. The inter-rater reliability for the attributions is .73 on average with each attribution type having the following Pearson correlation: positive internal: .86, negative internal: .61, positive external: .75 and negative external: .73.

Beginning with the population of firms in the pharmaceutical industry, we excluded observations that involved less than two attributions in their MD&A since a meaningful inference of managerial cognition may be limited when there are few attributions. Furthermore, given our variables of interest, observations where firms did not report their R&D expense in the following year, where sales in the base year was zero, or where firms made zero internal attributions or external attributions were not included in the regressions. Thus, the final data that we use in our study consist of 144 firms and 252 firm-year observations.

3.2 Variables and measures

3.2.1 Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is corporate entrepreneurship (CE). In line with Zahra (Reference Zahra1995), Hoskisson, Hitt, Johnson, and Grossman (Reference Hoskisson, Hitt, Johnson and Grossman2002) and Dalziel, Gentry, and Bowerman (Reference Dalziel, Gentry and Bowerman2011), we capture CE via a change in R&D spending. As our focus is on changed behavior over time, we measure the difference between R&D expenses in period t and t + 1scaled by firm assets in period t. Of importance is that our dependent variable is captured 1 year after all of our other variables. This temporal separation is important to avoid reverse causality. We capture the CE data via Compustat.

R&D is considered a highly relevant measure for capturing CE-related activities in R&D intensive industries such as biotech and pharmaceuticals (Dalziel, Gentry, & Bowerman, Reference Dalziel, Gentry and Bowerman2011). However, it is also a key input in other industries such as shipbuilding (Greve, Reference Greve2003), telecommunications, automotive, communication and cables, semiconductors (Cesaroni, Minin, & Piccaluga, Reference Cesaroni, Minin and Piccaluga2005), manufacturing (Swift, Reference Swift2016) and chemicals (Bauer & Leker, Reference Bauer and Leker2013), as well as high-performing firms in general (Hoskisson & Hitt, Reference Hoskisson and Hitt1988) as it facilitates organizational evolution and adaptation (Chen & Miller, Reference Chen and Miller2007). In particular, R&D allows firms to engage in exploration and exploitation activities and it has been shown to have clear effects on a business' ability to innovate (Baumann & Kritikos, Reference Baumann and Kritikos2016; Voutsinas, Tsamadias, Carayannis, & Staikouras, Reference Voutsinas, Tsamadias, Carayannis and Staikouras2018).

For the pharmaceutical industry in particular, CE and R&D spending are extremely important components of competitiveness (Dalziel, Gentry, & Bowerman, Reference Dalziel, Gentry and Bowerman2011; DiMasi, Hansen, & Grabowski, Reference DiMasi, Hansen and Grabowski2003). As patents on blockbuster innovation approach expiration dates (Hartmann & Hassan, Reference Hartmann and Hassan2006), generic competitors increase in significance (Grabowski & Vernon, Reference Grabowski and Vernon1996) and the rate of failures in pharmaceuticals increases (Gilbert, Henske, & Singh, Reference Gilbert, Henske and Singh2003), R&D spending is oftentimes the fuel that will drive future and long-term competitiveness. Further, this is the main source of corporate entrepreneurial activity that pharmaceutical companies engage in, since the R&D spending is highly related to patents earned, which is the main source of innovation and competition in this industry (Dunlap-Hinkler, Kotabe, & Mudambi, Reference Dunlap-Hinkler, Kotabe and Mudambi2010). R&D spending is also under the purview of top management and their efforts to promote CE. In contrast, lower levels of management might focus on alternate aspects that build into CE, such as experimentation or flexibility in job behavior (Hornsby et al., Reference Hornsby, Kuratko, Shepherd and Bott2009). As such, we believe that R&D spending is an appropriate measure of CE given its importance in the pharmaceutical industry and since it would be at the discretion of top management.

3.2.2 Independent variable

We capture Slack for any given year by subtracting current liabilities from current assets for the year t, and scaling it by firm assets in year t. Slack captures the excess liquidity or working capital available to the firm and reflects resources that are available and not yet committed to any specific purpose by the firm (Cheng & Kesner, Reference Cheng and Kesner1997; Dimick & Murray, Reference Dimick and Murray1978; Latham & Braun, Reference Latham and Braun2008; Nason, McKelvie, & Lumpkin, Reference Nason, McKelvie and Lumpkin2015; Tan & Peng, Reference Tan and Peng2003). In other words, this view of slack is in line with ‘high discretion’ slack that can be more easily used to achieve organizational goals (George, Reference George2005). In the pharmaceutical industry, this measure of slack plays a particularly important role as it reflects the amount of free cash that is available to the firm to allocate among entrepreneurial activities (such as R&D) and non-entrepreneurial activities (such as administrative expenses). Since the firms in our study are publicly traded, we draw upon the official and audited accounting data available on Compustat.

3.2.3 Moderating variables

We capture two types of managerial attribution – internal attributions and external attributions respectively. Internal attribution orientation captures the extent to which top management feels that the internal efforts and actions by the firm resulted in good performance as opposed to bad performance. We calculate this by taking the ratio of net positive internal attributions (positive internal attributions – negative internal attributions) to a total number of internal attributions (positive internal attributions + negative internal attributions). While we considered using the original four attribution types: positive-internal, negative-internal, positive-external, negative-external, the number of attributions can be influenced by a range of factors, including the size of the MD&A section. Consequently, we focus on the ratio between the relative and total internal attributions in order to circumvent variance in a total number of attributions and emphasize an orientation (e.g., a ratio) rather than a count. As a ratio, the value can range from 1 to −1, where a ratio greater than zero implies that the firm makes more internal attributions to positive outcomes; a ratio below zero reflects that the firm makes more internal attributions to negative outcomes. Furthermore, we chose to create an orientation measure for internal (external) attributions, rather than treating positive internal (external) attribution ratio and negative internal (external) attribution ratio as separate variables, because (1) a single variable better captures the extent to which managers weigh the influence of their internal actions (or the external environment) on firm performance, (2) empirically, we cannot run the regression with both internal (external) attribution ratios simultaneously, since there is a perfect correlation between these, and the internal (external) attribution variable we choose to drop affects the results, and (3) the orientation measure allows us to capture both types of internal (external) attribution, i.e., positive and negative, while improving model strength due to the presence of fewer variables.

External attribution orientation captures the extent to which top management links the external factors which are beyond the firm's control to good performance as opposed to bad performance. It is the ratio of net positive external attributions (positive external attributions – negative external attributions) to the total number of external attributions (positive external attributions + negative external attributions). Similar to the internal attribution orientation, the value for this measure can range from 1 to −1, where scores greater than zero indicates that the firm makes more external attributions to positive outcomes, and those below zero indicate that the managers believe that the external environment's influence has been more negative.

3.2.4 Control variables

We also employ several control variables. First, we control for firm performance in the current period by including sales growth. We capture percentage sales growth over a 1-year period, measured as the (salest-salest −1)/salest −1. This helps to capture the firms' most recent performance. We also include a variable for firm age, which is calculated by subtracting the firm founding year from the current year. We include a binary dummy variable if the firm carried out any acquisitions in the current year. This helps to control for important organizational change activities that might otherwise skew results.

Results

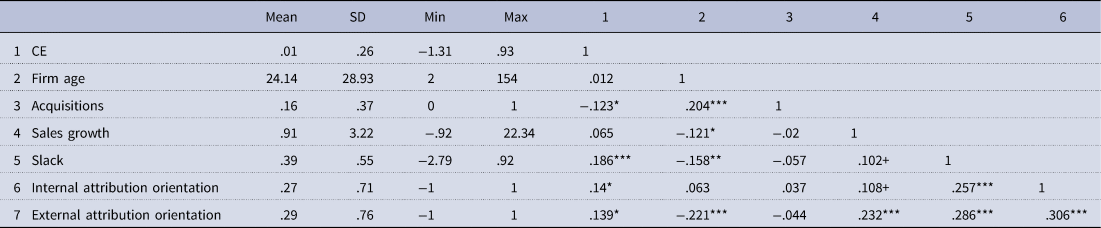

Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for the main variables in the study. The bivariate correlations are generally low with the highest correlation reaching .306. Given historical cutoffs within the social sciences, this suggests that the risk of multi-collinearity is low (Cohen, Reference Cohen2013). Since we draw our data from multiple sources, including audited performance data, there is a limited risk for source bias. Nevertheless, it is prudent to run a variance inflation factor (VIF) test to examine whether our variables are suffering from high multicollinearity. The results of a VIF test of all independent variables contained in Table 2, and their interactions used in Model 3, indicate that the highest individual VIF is 3.12, well below the common threshold of 10 (O'Brien, Reference O'Brien2007). This further supports our belief that multicollinearity is not impacting the tenor of our results.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations and descriptive statistics

Notes: ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, +p < .10. Summary statistics are for unstandardized variables. All variables are winsorized.

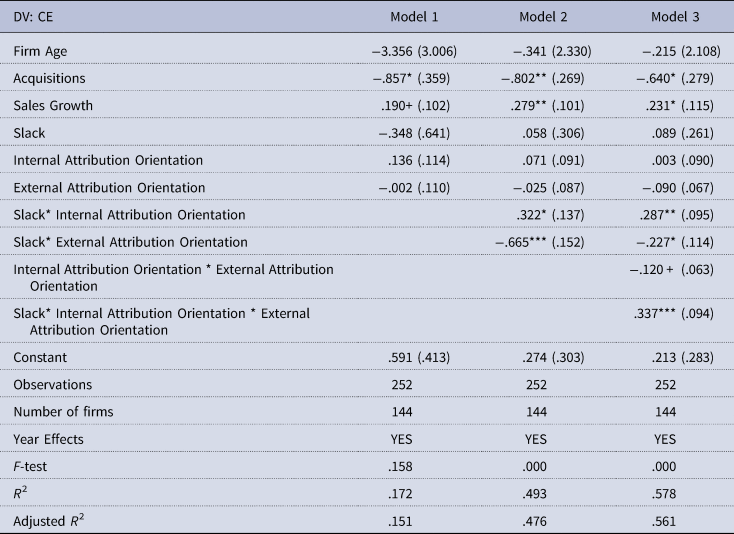

In order to test our hypotheses, we performed a hierarchical regression analysis. Since we have panel data, we ran a fixed-effects model, and used a White (Reference White1980) adjustment to correct our standard errors for heteroscedasticity. We winsorized all non-binary variables at 1% to remove influential outliers. For ease of interpreting the interaction effect, we also standardized all the non-binary variables. Table 3 provides the results of our hierarchical regression.

Table 3. The effect of slack and managerial attributions on CE using panel regression

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses; Fixed Effects Model and clustered by firm; 252 firm-year observations; ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05, +p < .10. All variables are winsorized except the binary variable. CE and slack are scaled by total assets.

In Model 1, we included all the independent and control variables without any interactions. While the attribution variables have no direct effect on CE, we see that one of the control variables (acquisitions) is statistically significant (p < .05). In Model 2, we included the interaction terms needed to examine Hypotheses 1 and 2. The regression suggests a positive (β = .322) and statistically significant relationship (p < .05) of the interaction between slack and internal attribution orientation on CE. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. The interaction between slack and external attribution orientation has a negative (β = −.665) and highly significant effect (p < .001) on CE. Thus, Hypothesis 2 is also supported.

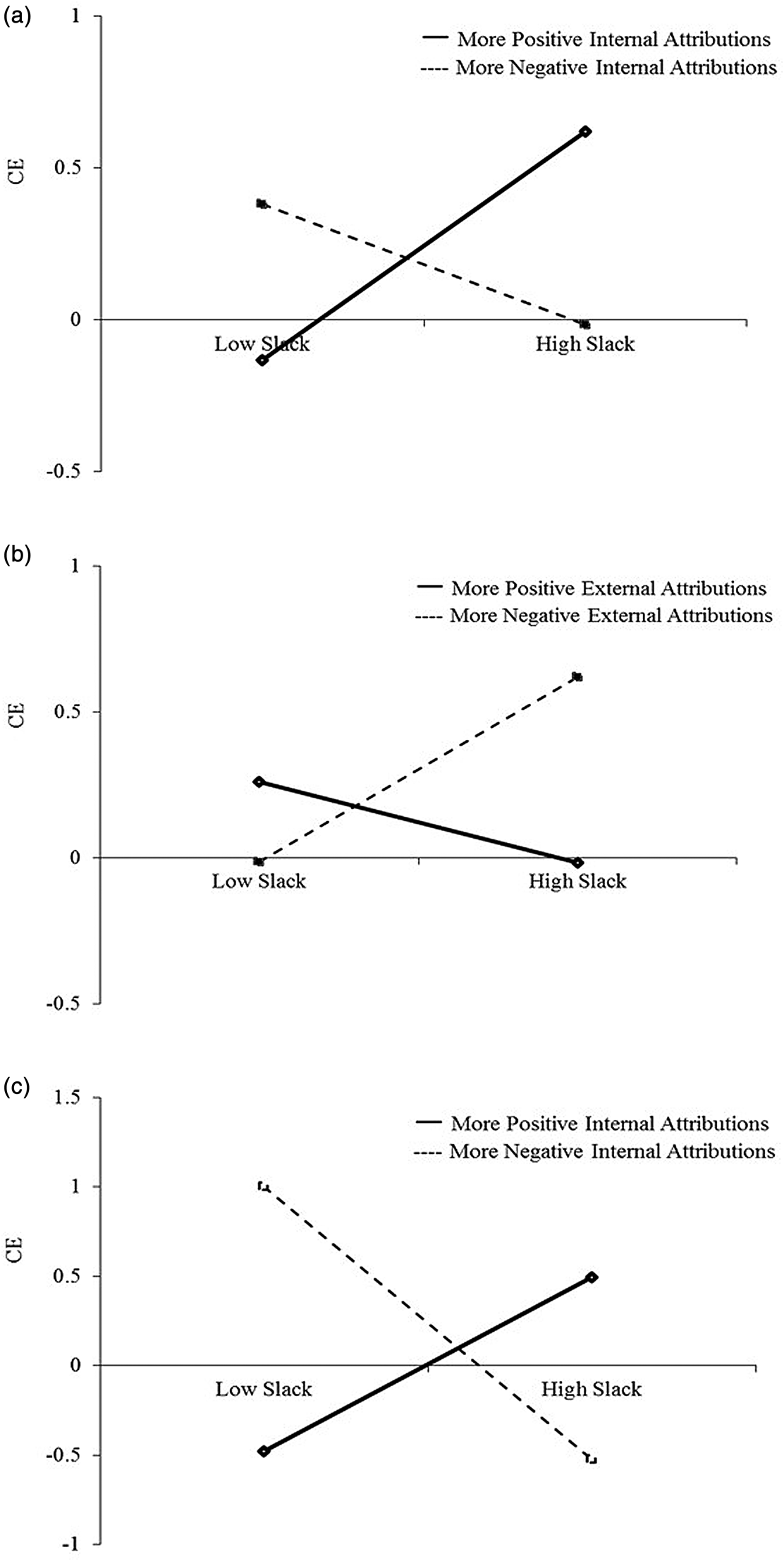

In Model 3, we present the full model which includes the three-way interaction of interest for Hypothesis 3. The regression suggests a positive (β = .287) and statistically significant relationship (p < .01) of the interaction between slack and internal attribution orientation, continuing support for Hypotheses 1 and 2. The interaction between slack and external attribution orientation has a negative (β = −.227) and statistically significant effect (p < .05) on CE. To better interpret these results, we present the interaction effect of slack with the two attribution variables. Figures 2a and 2b illustrate the validity of Hypotheses 1 and 2. It shows that CE increases with slack when firms make relatively more positive internal attributions or negative external attributions.

Figure 2. Moderating Effects of Internal and External Managerial Attributions on the Relationship between Slack and CE (based on Model 3). (a) Interaction between Slack & Internal Attributions. (b) Interaction between Slack & External Attributions. (c) Interaction between Slack & Internal Attributions for Firms with More Positive External Attributions.

Finally, the regression results show a positive (β = .337) and statistically significant relationship (p < .001) between slack, internal attribution orientation, external attribution orientation and CE. Figure 2c shows this interaction effect for firms that make relatively more internal attributions to negative outcomes than positive outcomes. As hypothesized, when firms make more internal attributions to negative outcomes, external attribution to positive outcomes weakens the relationship between slack and CE. Thus, Hypothesis 3 is also supported. In all our models, acquisitions have a significantly negative effect on CE (p < .05) while sales growth has a positive effect on CE (p < .10).

Discussion

The goal of this paper is to examine the role of managerial attribution of firm performance on the relationship between slack and CE. We argue, and empirically find, that attributions by top management influence the way in which organizational slack is used for pursuing CE activities. This is an important overall finding for two reasons. First, it provides a new lens to better understand CE activities. While CE studies have argued for greater consideration of the role of managerial cognition in entrepreneurial activities (Ireland, Covin, & Kuratko, Reference Ireland, Covin and Kuratko2009; Phan, Wright, Ucbasaran, & Tan, Reference Phan, Wright, Ucbasaran and Tan2009), little work has been done toward shedding new light on that important component. We position managerial attribution as a salient part of managerial cognitions. Our findings suggest that management narratives of attributions are a potentially useful reflection of how managers weigh their internal strengths and perceived risks for future action. To that end, our findings show that both the internal and external attributions affect CE, advancing research on CE beyond structural and organizational factors such as organizational culture and reward systems (Hornsby, Kuratko, & Zahra, Reference Hornsby, Kuratko and Zahra2002; Kuratko, Reference Kuratko2007). Further, we believe that managerial attribution can be a way forward in examining how managerial cognition affects other forms of strategic behavior beyond entrepreneurial efforts. For instance, our study can be viewed as extending studies such as Bromiley and Washburn (Reference Bromiley and Washburn2011) work on the effect of firm aspirations on cost-cutting strategies. It would also be interesting to enrich the context within which we study the impact of managerial attributions. One way to do this could involve examining other forms of CE, such as strategic alliances, joint ventures, and spinoffs.

Second, we find that the nature and direction of managerial attribution affect slack's relationship with CE activities. The use of slack for CE activities is risk-inherent endeavors carried out by firms (Hornsby et al., Reference Hornsby, Kuratko, Shepherd and Bott2009; Wiklund & Shepherd, Reference Wiklund and Shepherd2005), whereby firms take more risks when they believe that their internal efforts have a worthwhile impact on organizational performance. This is consistent with prior studies which find that entrepreneurial and risk-taking behavior is linked to positive attribution of performance to internal factors (Kaufmann, Welsh, & Bushmarin, Reference Kaufmann, Welsh and Bushmarin1995; Tang, Tang, & Lohrke, Reference Tang, Tang and Lohrke2008). In other words, firms engage in increased entrepreneurial behaviors when performance is viewed as being within management control. Similarly, we find that firms lower the use of slack for CE when management thinks that external, rather than internal factors are producing the firm's positive outcomes. We also find that firms respond to negative perceptions of the external environment by increasing their use of slack for CE. This is in keeping with the prediction that negative external attribution facilitates escalation of commitment and reactance when the freedom to engage in a behavior is restrained by external forces.

Our study may have important implications to managerial attribution more broadly. Our findings differ from previous research relating attributions to entrepreneurial behavior (Eggers & Song, Reference Eggers and Song2015; Gatewood, Shaver, & Gartner, Reference Gatewood, Shaver and Gartner1995; Yamakawa, Peng, & Deeds, Reference Yamakawa, Peng and Deeds2015). In these studies, the link between internal attribution and entrepreneurial behavior is examined separately from the link between external attribution and entrepreneurial behavior. However, firms make internal and external attributions in relation to different outcomes simultaneously. Thus, we consider the interaction between these two attributions, instead of limiting it to the effect of each attribution.

Further, our findings raise questions regarding the appropriateness of solely relying on prospect theory in determining firm risk-taking. Prospect theory has been previously used to understand managerial risk-taking behavior both at the individual and organizational levels. Kahneman and Tversky (Reference Kahneman and Tversky1979) laid out some of the foundational ideas for decision making under risk by proposing that individuals assess outcomes in relation to a reference point and adopt a gain or loss frame if the potential outcome falls above or below the reference. However, what makes for an appropriate reference point is not consistent across all firms (Bromiley, Reference Bromiley2010). By directly capturing top management's assessment of the most current change in performance rather than firm's level of performance relative to others in the industry or historical performance, we are able to better capture manager's expectation regarding risky investments.

The findings with respect to the moderating effect of attributions also have interesting implications for entrepreneurship in general, rather than only CE. The majority of attribution studies within the entrepreneurship literature have been at the individual level and address issues such as the impact of attributions on failure, experience, hindsight bias (Cardon, Stevens, & Potter, Reference Cardon, Stevens and Potter2011; Mantere et al., Reference Mantere, Aula, Schildt and Vaara2013; Ucbasaran et al., Reference Ucbasaran, Westhead, Wright and Flores2010) and future entrepreneurial efforts. In contrast, our study confirms that attribution effects exist at the organizational level. As a consequence, this has implications for organizational decision making as well as individual-level attribution studies in entrepreneurship. For instance, could attributions, in the light of prospect theory, explain entrepreneurial cognition and the entrepreneur's decision to pursue self-employment or opportunities identified? Or to what extent would a ‘failing’ year of performance lead to substantive changes to entrepreneurial behavior in the future? Questions occurring at the intersections of entrepreneurship and organizations might address the role of attributions within founding teams or in family businesses and decision making. For instance, how do attribution differences within founding teams affect decision quality? What effect does the relationship among team members have on the attributions that are made regarding performance?

Finally, our study advances our understanding of the use of slack in CE, particularly through its use in R&D. We find no direct effect of slack on CE. This confirms prior findings which suggest that slack alone is not an important determinant of CE (Geiger & Makri, Reference Geiger and Makri2006; Nohria & Gulati, Reference Nohria and Gulati1996). Instead, we find that the role of slack in directing firm's CE spending is defined in relation to managerial attribution. This offers a novel theoretical explanation for the inconsistent findings and temporal fluctuations in the literature related to the slack-CE relationship (Cuervo-Cazurra & Un, Reference Cuervo-Cazurra and Un2010; Filatotchev & Piesse, Reference Filatotchev and Piesse2009; Wales, Monsen, & McKelvie, Reference Wales, Monsen and McKelvie2011). Indeed, the inconsistencies in the literature implicitly support the inclusion of moderators in explaining the slack-CE relationship. Future efforts could likewise explore other cognitive, organizational, and environmental moderators.

Limitations

Although we have sought to conduct a rigorous study which allows us to gain a better understanding of how managerial attributions affect the use of slack for CE, it has several limitations. First, our measure of attribution is based on the MD&A sections of 10-Ks. Since these are publicly available documents, they are susceptible to impression management or bias in the sense that they may not reflect accurate interpretations of previous performance. While this possibility exists, previous research has found that the MD&A is largely reflective of the attitude of top management (Baginski, Hassell, & Hillison, Reference Baginski, Hassell and Hillison2000; Baginski, Hassell, & Kimbrough, Reference Baginski, Hassell and Kimbrough2004) and is subject to scrutiny by the Securities and Exchanges Commission. As such, these documents are often the basis of investor decisions (Clatworthy & Jones, Reference Clatworthy and Jones2003) and are more reliable than other communications such as press releases and interviews. Furthermore, the attribution bias which is ascribed to impression management is shown to exist even in contexts where its usefulness in enhancing self-presentation is relatively low. This suggests that the bias stems from the cognition of the actors involved (Clapham & Schwenk, Reference Clapham and Schwenk1991; Michalisin, Karau, & Tangpong, Reference Michalisin, Karau and Tangpong2004), and that it is therefore predictive of consequent organizational actions. Finally, examining MD&As also helps overcome retrospective bias issues inherent in questionnaires or structured interviews. Nonetheless, future research can look at other potential sources of attribution information such as firm's internal documents of communication.

Second, while our focus has been to explain changes in future behavior, due to the time-consuming nature of manually coding attribution, we restricted our study to 2 years of data. However, the effect of managerial attributions on slack may take longer than 1 year to take place, given the necessary changes in resource structures needed to effectively engage in CE and the time needed to see the impact of R&D undertakings. A more longitudinal dataset would allow for further inferences regarding the stability of managerial attributions and the effects of changing attributions within a firm.

Relatedly, our study is restricted to the pharmaceutical industry. While this allows us to control for environmental heterogeneity, we acknowledge that this limits the generalizability of our findings. The pharmaceutical industry offers an appropriate context to understand CE, given the importance of R&D investments to future financial performance. However, future work can be conducted in other industries in order to overcome the contextual boundaries of our study.

Finally, we have examined one type of a CE endeavor: R&D spending. While this is an important input into the corporate entrepreneurial process, and one that is under managerial discretion, there are other measures that might capture entrepreneurial action within a firm. Research has shown that CE activities can be captured using multiple measures and operationalizations (Eggers & Kaplan, Reference Eggers and Kaplan2009; Keil, Maula, Schildt, & Zahra, Reference Keil, Maula, Schildt and Zahra2008), especially given the heterogeneous nature of CE (Nason, McKelvie, & Lumpkin, Reference Nason, McKelvie and Lumpkin2015). Many of these different activities may be at various levels of the organizational hierarchy (Hornsby et al., Reference Hornsby, Kuratko, Shepherd and Bott2009; Hornsby, Kuratko, & Zahra, Reference Hornsby, Kuratko and Zahra2002) or involve engaging with other external firms (Patzelt et al., Reference Patzelt, Shepherd, Deeds and Bradley2008). Studies that more deeply embrace the multiple operationalizations and views of CE as part of understanding the role of slack and managerial attribution are welcome and encouraged.

Conclusion

Attribution theory has key implications for how organizational leaders act based on the perception of their firms' internal workings and environment. In this study, we utilize the predictions implied in attribution theory to elucidate on the relationship between organizational slack and CE. We do this by examining how top management's internal and external attributions for firm performance affect their risk-taking propensity. Consistent with the mainstream predictions of attribution theory, we find that firms engage more slack resources for CE when they have a more positive view of their internal workings. Additionally, we further extend the predictions of attribution theory (Harvey & Martinko, Reference Harvey, Martinko and Borkowski2009) by examining the interaction effect of internal attributions with external attributions. Consistent with learned helplessness, when management favors external attributions with positive firm performance, and internal attributions with negative firm performance, it discourages the use of slack for CE. Conversely, consistent with the idea of empowerment, when management favors internal attributions with positive firm performance and external attributions with negative firm performance, it encourages the use of slack for CE. We believe that future research can build upon the integrative framework developed in our study to understand the role of decision-maker cognition in CE and more broadly, in entrepreneurship.

Appendix 1. Coding Scheme

Objective. To identify the causes to which a company attributes changes in specific performance measures.

What We Are Looking for in the Management Discussion and Analysis

1. Causation: This is indicated by keywords such as (but not limited to) because, as a result, resulting from, with, following, contributed to, led to, due to, impact of, accounting for, results were achieved with, resulted from, associated with, primary driver, represented, thereby, reflecting.

2. Performance

• Text must mention a change in performance.

• Look out for keywords such as sales/revenue (market share), profit/loss (profit margin), income (net income, other income, interest income), earnings (earnings per share), or performance.

• This performance can be overall company performance or performance of a specific company segment, product line or product, or subsidiary

• Coding is for performance specific to the year of the annual report. For instance, if you are coding Company A's 2005 10-K, the coding is for the increase or decrease in sales for the year 2005, not 2004 or 2006.

• Do not include “We had more operating income, because we had more sales” kind of statements.

• Do not code expenses, do not include “cash used” or “cash provided,” liquidity, or capital.

How to Code an Instance of Causal Attribution. If you are attributing an improvement in performance to an internal (external) cause, it is internal (external)-positive attribution. If you are attributing a worsening of performance to an internal (external) cause, it is internal (external)-negative attribution.

1. Positive and negative attribution: Change in performance is indicated by words such as increase/decrease, strengthen/weaken, positive/negative, growth/decline, improve/worsen. Thus, the direction of change must be clear, otherwise do not code. The only exception is loss. In case of loss, companies may attribute sustained loss (rather than an increase or decrease) to some cause.

2. Internal attribution: Attributions that are related to firm-specific factors are coded as internal. Thus, internal attribution is made when performance is positively or negatively affected by a particular division of the firm, firm-level decisions, specific products launched by the firm, product recall, general legal expenses, research or administrative expenses, operational efficiency, higher cash balances, advertising, marketing, and so on.

3. External attribution: Attributions related to factors not directly under the control of the firm are coded as external. Thus, external attribution is made when performance is positively or negatively affected by the following:

◦ Irregular or unforeseen circumstances or random fluctuations/seasonality – for example, a severe flu season, a full year of sales in the current year as opposed to some months of sales in the previous year. “It is because we did better last year” kind of reasoning suggests fluctuations/irregular earnings. Words such as unusual and unexpected can be an indication of irregular causes.

◦ Regulation and media – for example, Food and Drug Administration approval, new tax, adoption of accounting standard following some Financial Accounting Standards Board statement, publicity

◦ Macroeconomic factors – for example, changes in interest rates, exchange rates

◦ Competition – for example, the introduction of generic products, market share loss to rival firms

◦ Legal issues – for example, lawsuits, payments related to lawsuits (Note: general legal expenses are classified under internal.)

◦ Market – for example, change in demand, changes in consumer preferences, change in number. Of customers or independent distributors

◦ Supplier – for example, raw material costs, delivery of raw materials

◦ Partner – for example, joint ventures, collaboration agreements, alliances, strategic partnerships, copromotions, licensing, manufacturing or distribution agreements

Note. From “Author” (2017). [Title omitted for blind review]

Parvathi Jayamohan Parvathi Jayamohan is an assistant professor of management at the Bertolon School of Business at Salem State University. Her research interests include managerial attributions and family firms.

Todd Moss Todd Moss is the chair of the Department of Entrepreneurship and Emerging Enterprises and an associate professor of entrepreneurship at the Whitman School of Management at Syracuse University. He has a wide range of research interests including social entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial orientation, and most recently, microfinancing

Alex McKelvie Alex McKelvie is the associate dean and a professor of entrepreneurship at the Whitman School of Management at Syracuse University. His research interests include corporate entrepreneurship, family firms, and new firm growth

Michael Hyman Michael Hyman is an assistant professor of accounting at the Girard School of Business at Merrimack College. His research interests include information processing, financial disclosure, and asset pricing