Glioma is a central nervous system tumor that originates from the glial cells of human brain and represents about 80 % of adult malignant brain cancers(Reference Ostrom, Gittleman and Liao1). Some of the identified risk factors include male sex, advanced age, certain ancestry (European), allergic/atopic conditions and genetic predisposition, as well as ionising radiation from medical and environmental exposure(Reference Braganza, Kitahara and Berrington De González2,Reference Amirian, Zhou and Wrensch3) . However, the role of modifiable lifestyle-related factors and diet/nutrition, including coffee and tea consumption, is less well investigated(Reference Creed, Smith-Warner and Gerke4).

The role of various nutritional factors in promoting or preventing brain cancer is increasingly being studied. Coffee and tea have long been popular drinks for people around the world and their consumption has been hypothesised to lower the risks of some cancers, including glioma(Reference Nkondjock5). Both beverages contain abundant amounts of polyphenols, including flavonoids (predominantly in tea) and phenolic acids (predominantly in coffee) which have been shown to protect against cancer due to their antioxidative properties, ability to regulate heterogenous metabolite enzymes and modulate xenobiotic metabolite enzymes, and inhibit tumour promotion(Reference Creed, Smith-Warner and Gerke4,Reference Holick, Smith and Giovannucci6) . Cumulative antioxidant capacity found in coffee is higher than that found in any given fruit and vegetable(Reference Pellegrini, Serafini and Colombi7). However, the benefit of coffee or tea consumption on the risk of glioma is still controversial; two most recent studies published in 2020 showed conflicting results, similar to previous studies(Reference Creed, Smith-Warner and Gerke4,Reference Cote, Bever and Wilson8) . In this systematic review and dose–response meta-analysis, we aimed to assess whether coffee and tea consumption is related to the risk of glioma by synthesising the latest evidence from cohort studies. We also aimed to quantify the relationship and whether it is linear through dose–response meta-analysis. Additionally, we aimed to explore the cause of heterogeneity among these studies by investigating potential confounders.

Material and methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis follows the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) reporting guidelines. The protocol for this systematic review is registered in PROSPERO Database (CRD42020212303).

Eligibility criteria

We included research papers (both cohorts and case–control studies) that assessed the association between coffee and/or tea consumption with the risk of developing glioma. We excluded animal studies, abstract-only publications, preprints, review articles, commentaries, letters, case reports/series and studies that did not report key exposures and/or outcomes of interest.

Search strategy and study selection

We performed a systematic literature search using several electronic databases including PubMed, Embase, Scopus and the EuropePMC with keywords ‘tea’ OR ‘coffee’ OR ‘caffeine’ AND ‘glioma’ OR ‘glioblastoma’ OR ‘brain cancer’ for records published from inception up until 1 October 2020. The PubMed (MEDLINE) search strategy was ((tea)[All Fields] OR (coffee)[All Fields] OR (caffeine)[All Fields]) AND ((glioma)[All Fields] OR (glioblastoma) [All Fields] OR (brain cancer) [All Fields]). Full search strategy is supplied in Supplementary Figure 1. We also performed hand-searching for related articles. After compiling the initial records, duplicates were removed, and two authors independently assessed the titles and abstracts of the residual articles by applying inclusion and exclusion criteria. Authors in charge of performing literature searches are medical doctors with experience in performing systematic review and meta-analyses.

Data extraction

Two authors performed data extraction independently with the help of a standardised forms containing rows and columns for the first authors of the included studies, year, study design, age, sex, smoking status, alcohol drinking status, the outcome of interests and adjustment for covariates. These variables were chosen based on potential effect on the association between the exposure and key outcomes.

Exposures in the present study were coffee consumption and tea consumption. The main outcome of the present study was the incidence of glioma. The present study compared the association between the exposure of coffee and tea with the incidence of glioma, and the results were reported in relative risks (RR). We used the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the risk of bias and the quality of the included studies. This was performed by two independent authors, and discrepancies that arise were resolved through discussion.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 16.0 (StataCorp LLC). Pooled effect estimates were reported in RR and its 95 % CI. We used random-effects model for all analyses regardless of heterogeneity. All P-values for the effect estimate were two-tailed, and a value of ≤ 0·05 was considered as statistically significant. Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistic were used to evaluate inter-study heterogeneity, and I2 values > 50 % and P-value < 0·10 indicated significant heterogeneity. Studies with at least three quantitative classifications were eligible for dose–response meta-analysis. We performed a two-stage random-effects dose–response meta-analysis using generalised least-squares regression trend estimation based on log RR across coffee/tea consumption intervals. The potential for non-linear relationship was evaluated using restricted cubic splines with three-knot model. We used a restricted maximum likelihood multivariate random-effects meta-analysis to pool the effect estimates. A Wald-type test was used for evaluating non-linearity through testing regression coefficient of the second spline. Cote et al. study and Holick et al. were derived from the same cohort. Since Cote et al. was newer, it was included in the comparison between highest v. lowest category. However, only Holick et al. meets the requirement for dose–response analysis. Thus, both studies were included for different analysis. Regression-based Egger’s test was performed to evaluate the presence of small-study effects and inverted funnel plot analysis for qualitative assessment of publication bias. In case of funnel plot asymmetry, non-parametric trim-and-fill analysis of publication bias with linear, L0 estimator was performed. Restricted maximum likelihood random-effects meta-regression analysis was performed for the association between coffee and the risk of glioma, using age, sex, continent of origin, smoking and drinking (alcohol) as covariates, one at the time. Sensitivity analysis was performed by removing case–control studies. Subgroup analyses that compared coffee consumption (4 cups/d v. < 1/d) and tea consumption (3–4 cups/d v. < 1/d) were performed, and these subgroup analyses were post hoc and determined based on the most frequent reporting.

Results

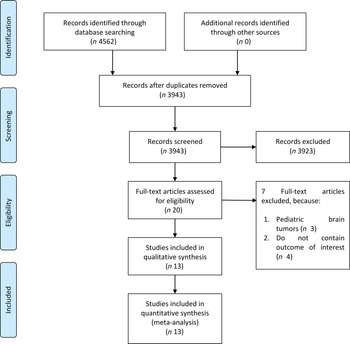

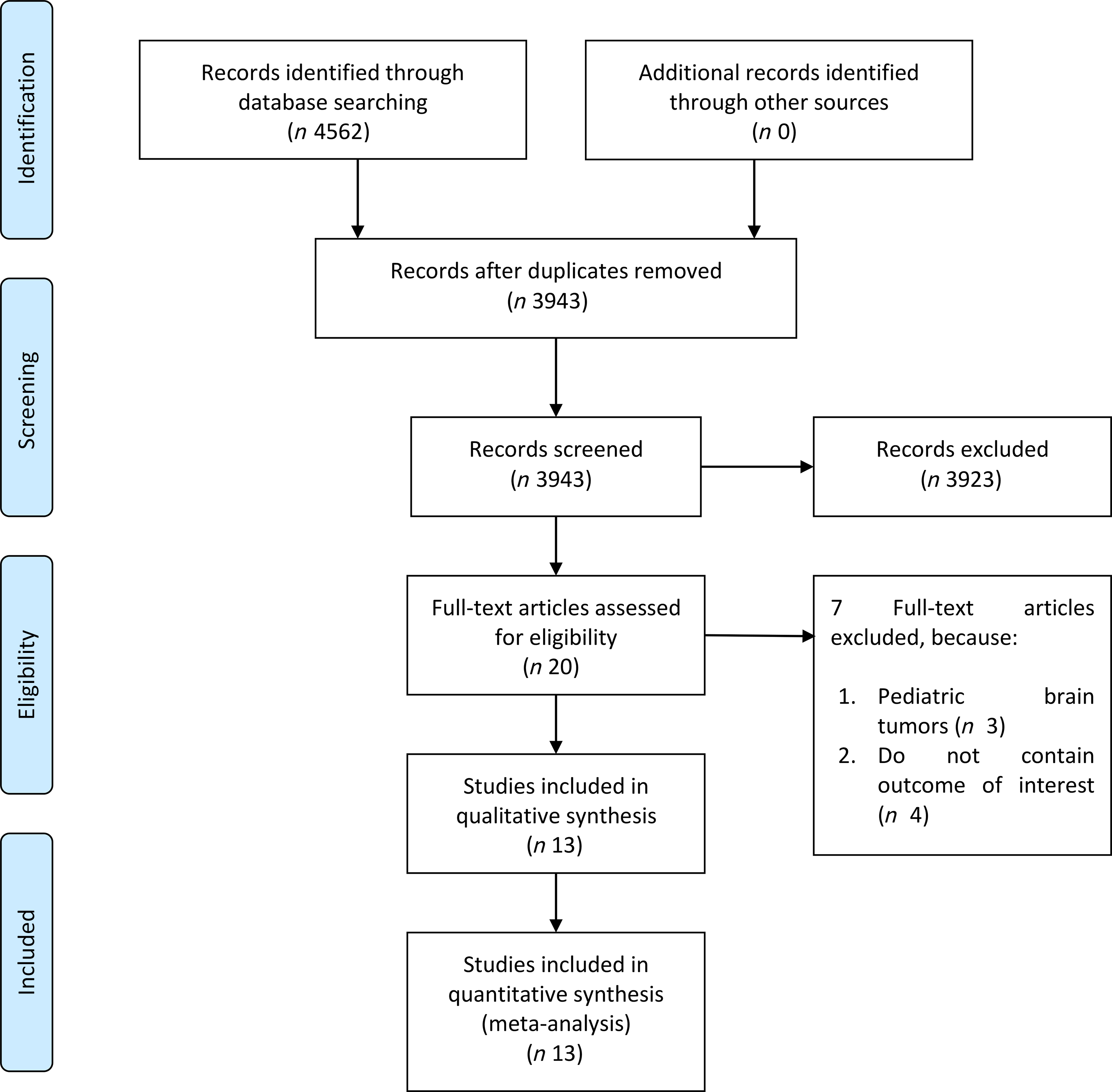

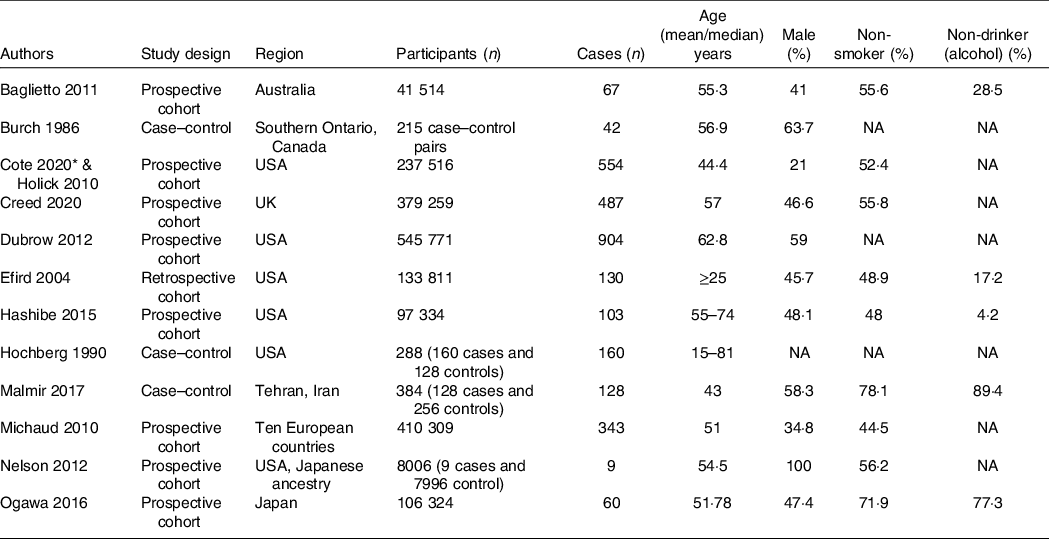

The flow chart for the study selection can be seen in Fig. 1. There were thirteen studies (twelve uniques studies) comprising of 1 960 731 participants with 2987 glioma cases included in this systematic review and meta-analysis(Reference Creed, Smith-Warner and Gerke4,Reference Holick, Smith and Giovannucci6,Reference Cote, Bever and Wilson8–Reference Efird, Friedman and Sidney18) . The baseline characteristics of the included studies can be seen in Table 1. Cote et al. and Holick et al. studies were derived from the same cohorts. Only cohort studies were included in the dose–response analysis.

Fig. 1. Study flow diagram.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the included studies

NA: not available/not reported/reported in different classification.

* Cote 2020 & Holick 2010 study was drawn from the same cohort.

Table 2. Baseline characteristics of the included studies (continued)

HR: Hazard Ratio, FFQ: Food Frequency Questionnaire, NOS: Newcastle–Ottawa Scale.

Highest v. lowest coffee consumption group

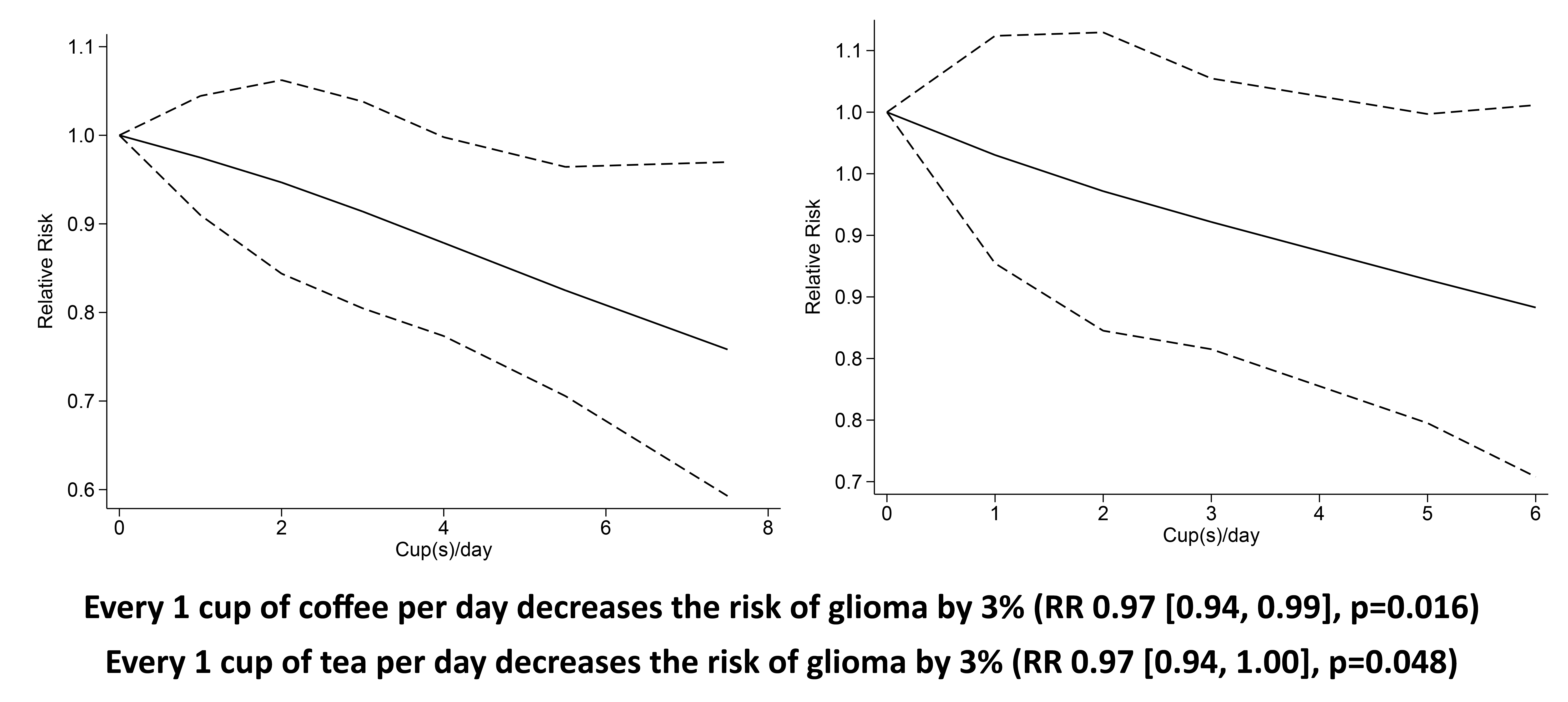

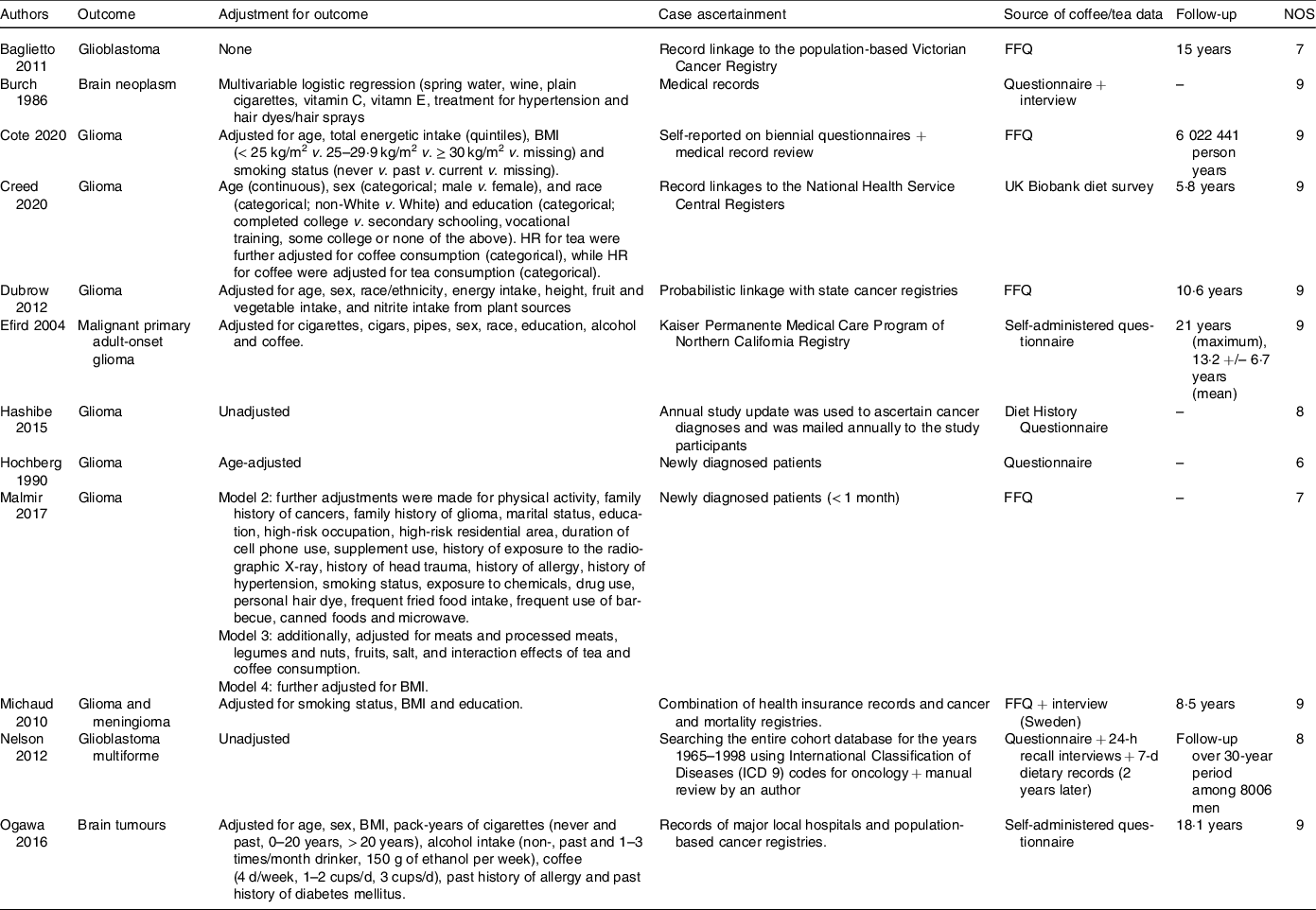

Higher coffee consumption was associated with a statistically non-significant trend towards lower risk of glioma (RR 0·77 (95 % CI 0·55, 1·03), P= 0·11; I2:75·27 %, P= 0·001). Subgroup analysis for comparison between more than four cups per d v. less than one per d (five studies) showed a borderline significant result (RR 0·81 (95 % CI 0·64, 1·02), P= 0·067; I2:0 %, P= 0·602). Dose–response meta-analysis showed that every one cup of coffee per d decreases the risk of glioma by 3 % (RR 0·97 (95 % CI 0·94, 0·99), P= 0·016). The dose–response relationship was borderline significant for non-linearity (P non-linearity = 0·054) (Fig. 2(b)).

Fig. 2. Coffee and the risk of glioma. (a) Comparison between the highest v. lowest coffee consumption groups. (b) Dose–response meta-analysis between coffee consumption and the risk of glioma with restricted cubic splines in a multivariate random-effects dose–response model. Relative risks (solid line) with 95 % CI (long dashed lines) for the association between coffee consumption and the risk of glioma. I-squared: I2; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Highest v. lowest tea consumption group

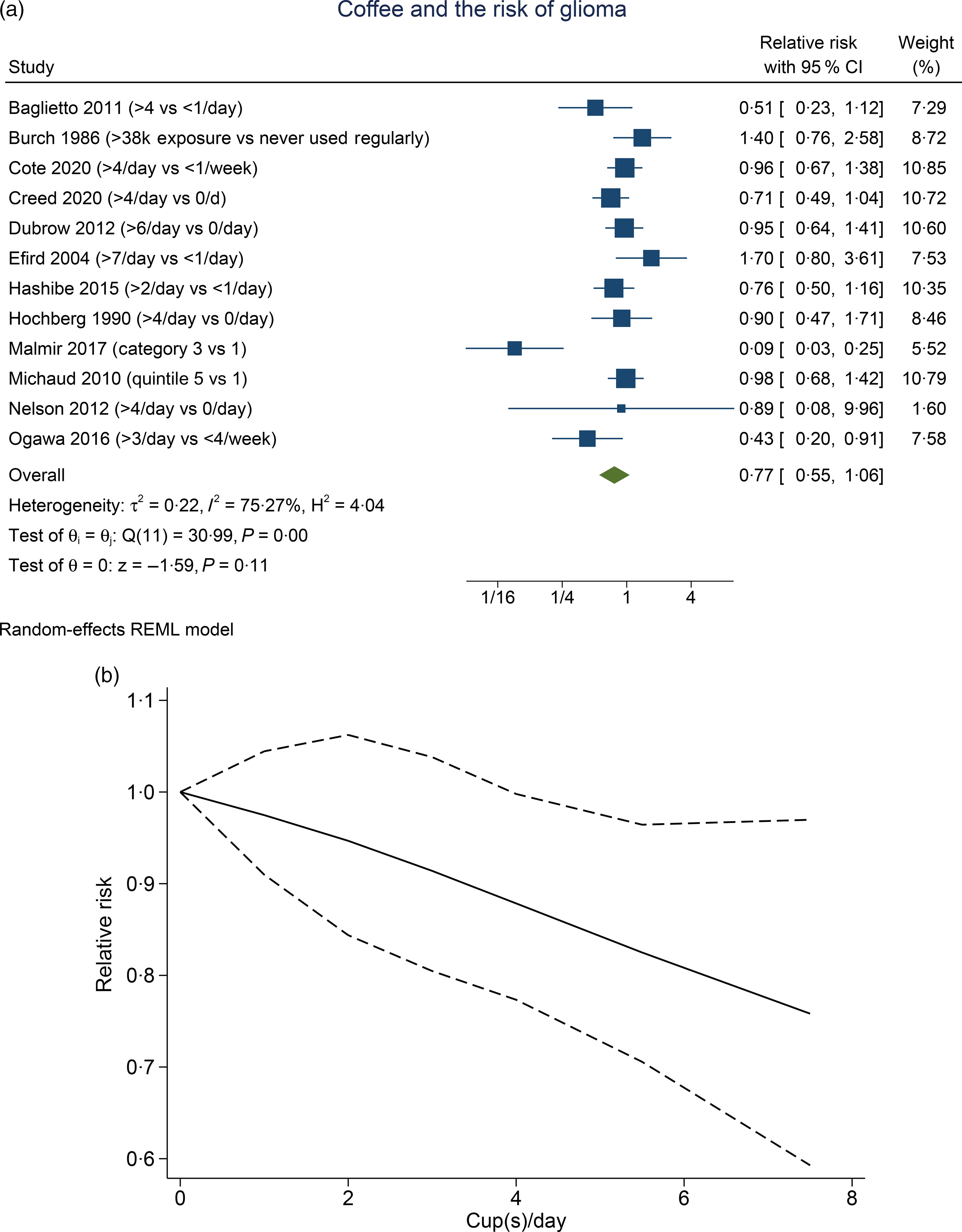

Higher tea consumption was associated with the lower risk of glioma (RR 0·84 (95 % CI 0·71, 0·98), P= 0·030; I2:16·42 %, P= 0·19). Subgroup analysis for comparison between more than three to four cups per d v. less than one per d (four studies) showed that tea was associated with risk reduction (RR 0·79 (95 % CI 0·65, 0·96), P= 0·020; I2:10·01 %, P= 0·373). Dose–response meta-analysis showed that every one cup of tea per d decreases the risk of glioma by 3 % (RR 0·97 (95 % CI 0·94, 1·00), P= 0·048). The dose–response relationship was linear (P non-linearity = 0·140) (Fig. 3(b)).

Fig. 3. Tea and the risk of glioma. (a) Comparison between the highest v. lowest tea consumption groups. (b) Dose–response meta-analysis between tea consumption and the risk of glioma with restricted cubic splines in a multivariate random-effects dose–response model. Relative risks (solid line) with 95 % CI (long dashed lines) for the association between tea consumption and the risk of glioma. I-squared: I2; REML, restricted maximum likelihood.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis by removal of case–control studies was performed. Higher coffee consumption was associated with reduced risk of glioma (RR 0·85 (95 % CI 0·72, 1·00), P= 0·046; I2:0 %, P= 0·230). Higher tea consumption was associated with lower risk of glioma (RR 0·81 (95 % CI 0·70, 0·93), P= 0·004; I2:0 %, P= 0·545).

Risk of bias assessment

Inverted funnel plot analysis showed a relatively symmetrical distribution apart from an outlier (online Supplementary Figure S1) for coffee. There is a slight asymmetry for the analysis on tea (online Supplementary Figure S2). Non-parametric trim-and-fill analysis of publication bias with linear estimator showed that after the imputation of two studies, the association between tea and glioma remains significant (RR 0·81 (95 % CI 0·69, 0·95)). Egger’s test showed no indication of small-study effects for both coffee (P= 0·153) and tea (P= 0·730).

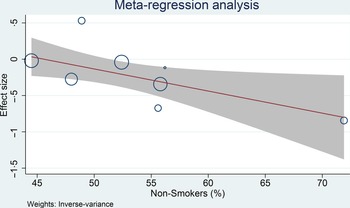

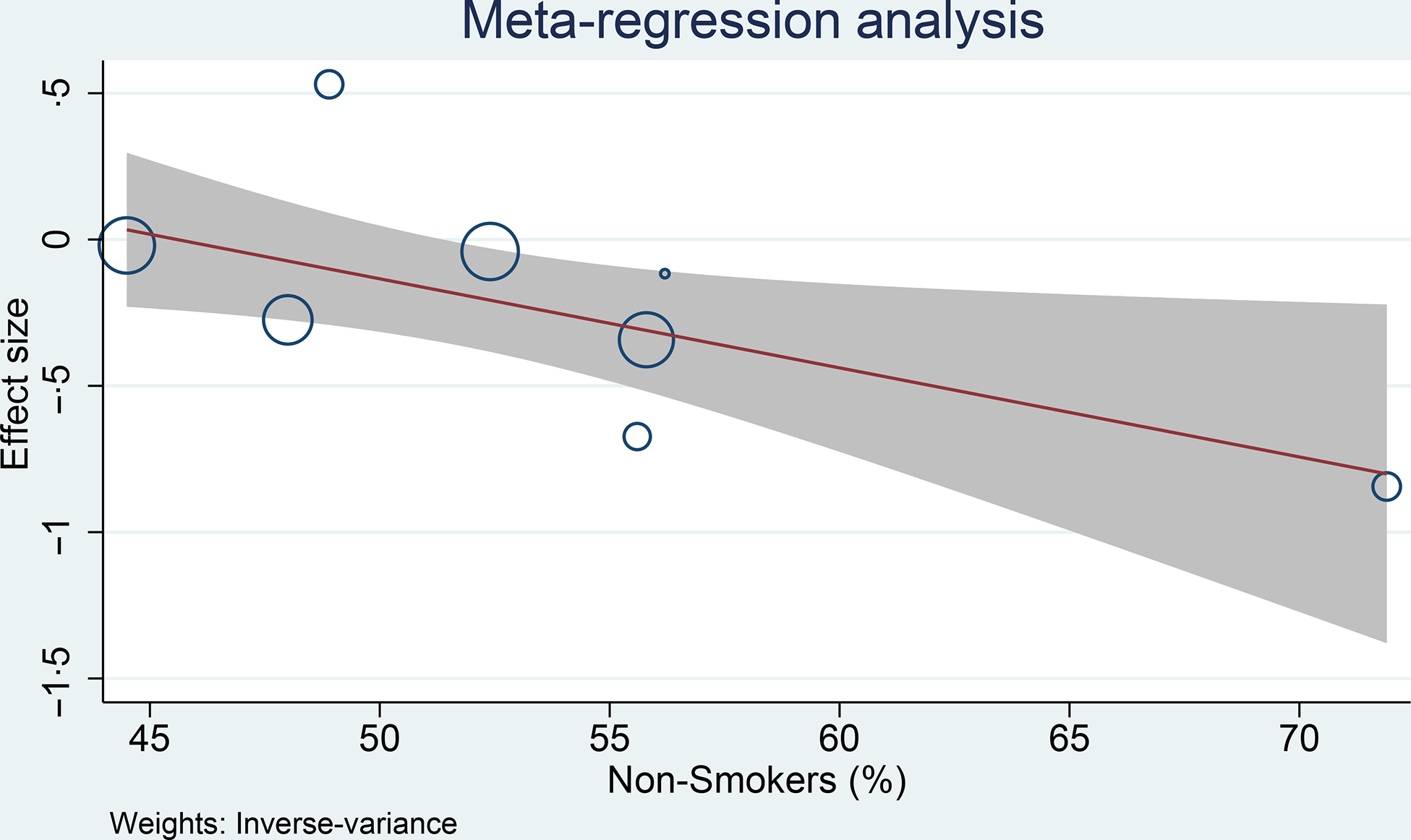

Meta-regression

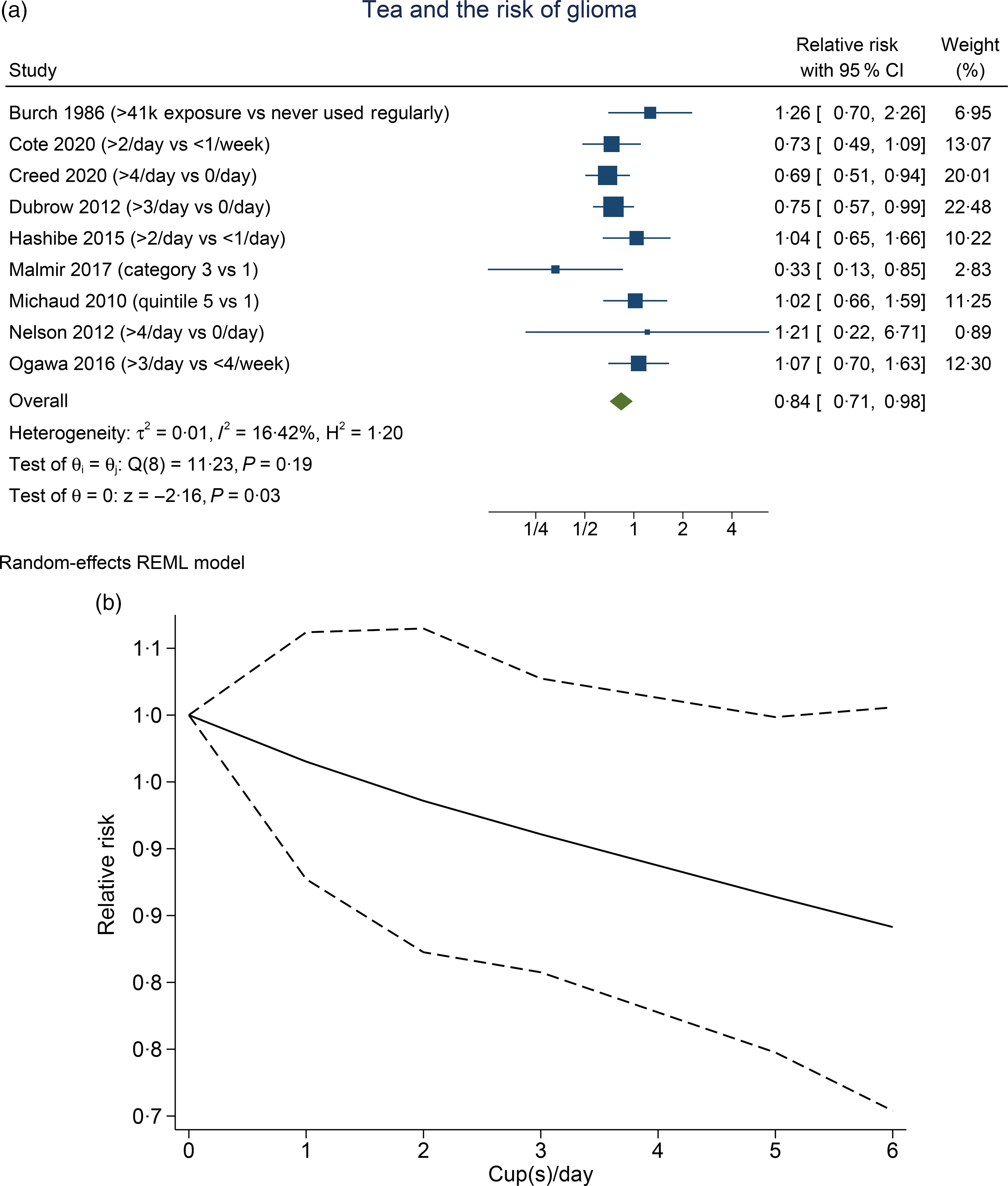

Meta-regression analysis was performed for cohort studies, and the relationship between coffee consumption on the risk of glioma was influenced by smoking (covariate: non-smoker, coefficient: −0·03, P= 0·029) (Fig. 4) and continents (North America, Europe and Asia-Pacific, P= 0·038), but not age (coefficient: −0·005, P= 0·765), male sex (coefficient: −0·004, P= 0·579) and alcohol consumption (covariate: non-drinker, coefficient: −0·01, P= 0·279). The risk reduction was greater in non-smoker and non-drinker. The most significant risk reduction occurred in the Asia-Pacific region.

Fig. 4. Meta-regression analysis showing the association between coffee and glioma was affected by smoking. 95 %CI; ![]() studies;

studies; ![]() linear prediction.

linear prediction.

Discussion

This meta-analysis showed that coffee and tea consumption was associated with a lower risk of glioma. Dose–response analysis showed a 3 % reduction in the risk of glioma for every one cup of coffee or tea per d. The dose–response was linear for the analysis on tea and potentially non-linear for the analysis on coffee.

We observed that in the pooled analysis of the highest coffee consumption v. the lowest, the result was borderline significant. Subgroup analysis of > 4 cups/d v. < 1 cup/d also showed a borderline significance with 0 % heterogeneity. However, upon sensitivity analysis, coffee was shown to reduce the risk of glioma with 0 % heterogeneity upon removal of case–control studies. This may indicate that the case–control studies introduced bias and heterogeneity to the analysis. The dose–response analysis, which excludes the case–control studies, also showed a significant risk reduction that is almost non-linear.

We performed meta-regression analysis on the cohort studies only, to reduce bias that may resulted from case–control studies. Meta-regression analysis showed that the risk reduction associated with coffee consumption was greater in non-smokers. Smoking has been shown to increase the risk of cancer, although the association is controversial in glioma(Reference Jacob, Freyn and Kalder19–Reference Holick, Giovannucci and Rosner23). Thus, smoking may negate the benefit of coffee consumption. Another possible confounder in the analysis was the continent where the study was located, and a greater risk reduction was found in the Asia-Pacific region. However, there is limited studies for the Asia-Pacific region as most of the studies are from North America. One of the studies that originated from Asia-Pacific was Ogawa et al. The author of the study acknowledged that only relatively few subjects drank coffee every day. Nevertheless, there is no indication that one study spuriously affects the RR of our pooled analysis.

Meta-analysis indicates that tea reduces the risk of glioma, and the significance remained after sensitivity analysis and subgroup analysis, indicating statistical robustness. The dose–response analysis also indicates a statistically significant risk reduction in a linear fashion. Removal of case–control studies in the sensitivity analysis results in 0 % heterogeneity. Similar to the prior analysis of coffee, case–control studies serve as the possible cause of heterogeneity in this analysis.

Funnel plot analysis was symmetrical for effect estimate related to coffee and asymmetrical for tea consumption; thus, indicating a possible publication bias related to tea consumption studies. Trim-and-fill analysis with a hypothetical imputation of the studies indicate that tea consumption will remain significant for glioma risk reduction should new studies are introduced.

Studies with case–control design might be biased due to psychological stress experienced by the newly diagnosed patients and the symptoms associated with the disease. This may impair the ability to recall or the willingness to fill the questionnaires. Control participants without glioma are often healthier and less stressful than patients with glioma. Prospective cohorts are less prone to bias due to data collection during a less stressful situation in terms of physical health and has a more comparable baseline. The quality of data in the cohort studies is mostly excellent and comparable to one another. However, a higher quality of data is expected in studies where source of coffee/tea data was derived from questionnaire and interview as opposed to questionnaire only. Different type of measurement may be a source of bias among the studies. Michaud et al. reported data from several European countries and data collection methods differed across the countries.

The follow-up length differs among the studies, which potentially contributed to heterogeneity. A comparison between exposures is often more pronounced when the events (and sample size) are higher. Also, whether the effect of coffee and tea gets stronger, stays the same or diminishes over time is unknown; thus follow-up time may affect the effect estimate. Based on the result of our analysis, heterogeneity among the cohort studies was 0 %; thus the difference in follow-up length may not contribute significantly to heterogeneity. While the others study evaluates all types of glioma, Nelson et al. only evaluate the incidence of glioblastoma. There were only nine cases in Nelson et al., which may have low statistical power to detect any significant difference resulting from coffee/tea consumption.

Various therapeutic effects of polyphenols found in coffee and tea may be helpful against many pathological conditions, including cancer(Reference Nkondjock5,Reference Yang, Chung and Yang24) . The epicatechin-3-gallate and epigallocatechin-3-gallate in tea have antiinflammation, anticarcinogenic, antiproliferative, antioxidant, antifibrosis and anticollagenase properties(Reference Chu, Deng and Man25–Reference Zeng, Zhao and Xu28). Additionally, epigallocatechin-3-gallate has been reported to reactivate methylation-silenced genes in cancer cells, including O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase (MGMT)(Reference Michaud, Gallo and Schlehofer13). Higher MGMT activation is postulated to protect against the development of various cancers, including glioma, whereas the genetic polymorphism of MGMT has been associated with the risk of glioma(Reference Michaud, Gallo and Schlehofer13). Similarly, chlorogenic acid, a polyphenol found in coffee, has antioxidative and antibacterial properties, as well as anticarcinogenic roles via 5' adenosine monophosphate- activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation(Reference Ogawa, Sawada and Iwasaki12).

Coffee and tea also contain methylxanthines (e.g. theophylline and caffeine) which have anti-inflammatory action and allow enhancement of cerebrospinal fluid production(Reference Han, Kim and Lee29). These small lipophilic molecules can cross the blood–brain barrier to encourage clearing or diluting of neurotoxins, thereby reducing the risk of glioma(Reference Creed, Smith-Warner and Gerke4). However, the effect on cancer progression may vary given the wide variety of brewing method and different types of coffee and tea(Reference Song, Wang and Jin30).

Specific brewing techniques can affect the concentration of certain substances found in coffee and tea, including caffeine(Reference Holick, Smith and Giovannucci6). For instance, 1 liquid oz (29·6 ml) of espresso obtained from pressurised brewing method contains 64 mg of caffeine, while 8 liquid oz (236·6 ml) of gravity-brewed coffee (e.g. filtered coffee) contains 96 mg of caffeine(Reference Gebhardt, Cutrufelli and Howe31). Variability inevitably leads to measurement errors, and total volume consumed per d may not reflect the actual consumption of compounds contained in coffee and tea accurately(Reference Michaud, Gallo and Schlehofer13). Previous study showed that filtered brew was associated with reduced any cause of mortality compared with unfiltered brew and no coffee consumption(Reference Tverdal, Selmer and Cohen32). Nevertheless, there is currently no evidence that indicate a specific type of brewing method influence the risk of glioma differently(Reference Holick, Smith and Giovannucci6).

Depending on the experimental condition, caffeine may facilitate and limit the development of malignant cells by reducing cerebral blood flow and eventually restricting access to oxygen and nutrients, thereby inhibiting angiogenesis and carcinogenesis(Reference Holick, Smith and Giovannucci6,Reference Jiang, Lan and Zhang33–Reference Liu, Song and Yan35) . With regard to glioblastoma, caffeine has been reported to decelerate the growth and invasion of glioblastoma and consequently prolong survival by inhibiting Ca release channel(Reference Kang, Han and Ku36), reducing hypoxia-inducible factors (HIF)-1α and vascular endothelium growth factor expression in glioblastoma cells(Reference Maugeri, D’Amico and Rasà37), reducing the invasion of glioma cells from different signalling pathways(Reference Cheng, Ding and Hueng38,Reference Chen, Chou and Ding39) and promoting forkhead box protein O1 (FoxO1)-Bim-mediated cell apoptosis(Reference Sun, Han and Cao40).

One of the limitations encountered in the present study is that we were unable to provide subset analysis on types of coffee and teas, and other specifics such as filtered or decaffeinated coffee because most of studies did not report it. Also individuals may also switch their types of coffee over time. Analysis of the cross-sectional studies might not be fully accurate due to recall bias; nevertheless, most of the studies were cohort. The source of data collection varies among the studies (i.e. FFQ, other questionnaire, with or without interviews, etc). Additionally, numerous confounders are present in the observational studies on lifestyle, and these confounders might not be adequately reported and adjusted. The significant summary measures in the present study were very much driven by a small number of studies. Thus, additional large and high-quality prospective cohorts are required before definite conclusion.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis showed that there is an apparent association between coffee and tea intake and risk of glioma.

Acknowledgements

None.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

R. P. conceived and designed the study and drafted the manuscript. R. P. and M. A. L. acquired the data and drafted the manuscript. J. H., A. F., R. P. and J. J. performed data extraction, interpreted the data and performed extensive research on the topic. R. P., R. V., A. F. and M. A. L. drafted the initial manuscript. R. P., R. V., N. G. and J. J. reviewed and performed extensive editing of the manuscript. R. P. performed the statistical analysis. All authors contributed significantly to the writing of the manuscript. All authors approve the final manuscript.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary material

For supplementary material referred to in this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114521000830