This part focuses on the principal terms of an intellectual property (IP) licensing agreement. Contrary to popular belief, save for online and “shrinkwrap” agreements (see Chapter 17), no two licensing agreements are exactly the same. Nevertheless, many licensing agreements share the same general layout and structure. Below is a rough summary of the different parts of a licensing agreement, with a few pointers regarding provisions that don’t merit a full discussion in the chapters that follow. In the Online Appendix to this book are samples of several different types of licensing and other transaction agreements, which you may wish to refer to as you use this book.

Introductory Material

The first few paragraphs of the agreement typically include the title of the agreement, the names of the parties, the effective date, and recitals framing the purpose of the agreement (see Section 13.1).

Definitions

Though they may seem routine, the defined terms in an agreement (those Capitalized or ALL CAPS terms that appear throughout the document) are among its most important terms. Many agreements include a section listing defined terms at the beginning (or, less frequently, at the end) of the agreement. The alternative to including a section devoted to defined terms is to define terms throughout the agreement “in line” (e.g., “the Parties shall conduct the research and development activities at 123 South Infinite Loop, Cupertino, California (the ‘Facility’)”). We will discuss important defined terms throughout the following chapters as they arise.

Activities and Deliverables

Many agreements require one or both parties to perform some activity or service – the development of a new technology, the manufacture of a product, the provision of an online service, or any of a thousand other things. The general framework for the performance of these activities is usually laid out in the agreement, along with references to any products, prototypes, plans or designs that are required to be delivered (usually referred to as “Deliverables”). If the services or deliverables are complex, then they may be described in more detail in any number of schedules or exhibits to the main agreement. Services relating to the development of IP are discussed in Section 9.2.

License Grants and Exclusions

The core of any license agreement is the license grant. Chapters 6 and 7 focus on the drafting and issues surrounding this key set of provisions.

IP Ownership and Management

Sometimes each party brings IP to a collaboration; sometimes new IP is developed during the course of a collaboration. These provisions describe which party or parties owns particular categories of IP, and how the parties allocate responsibility for managing that IP (e.g., prosecuting patents). These issues are discussed in Chapter 9.

Payments

Most license agreements involve the payment of funds by one party to the other. Chapter 8 addresses the many different variants by which parties are paid.

Representations, Warranties and Indemnification

By this point in a license agreement, most businesspeople have stopped reading. We are now entering lawyers’ territory, with a set of provisions that is both important and underappreciated. Representations, warranties and indemnification, discussed in Chapter 10, allocate liability among the parties for a host of potential issues.

Term and Termination

It is the rare agreement that lasts forever, so every agreement contains clauses relating to its duration and eventual end. These provisions are discussed in Chapter 12.

The Boilerplate

At the end of every agreement comes a set of terms – often running to several pages – that are seldom negotiated, but can become critically important under the right circumstances. These are covered in Chapter 13.

Signatures

Every agreement must evidence the mutual assent of the parties. Today, assent can be manifested in many ways – through email, text, spoken word or handshake. But by far the most common method used in license agreements, other than consumer clickwrap agreements, is the personal signature of an authorized representative of the signing party. If the identity of the signatory needs to be verified, signatures can be notarized.

Schedules

After the body of the agreement often come a variety of attachments. Schedules often contain lists or descriptions responsive to a particular section of the agreement. For example, if section 2.4 of the agreement requires the licensor to list all employees who are responsible for developing a particular technology, that list could be provided on schedule 2.4. The schedule is part of the agreement, but placed at the end for convenience.

Exhibits

Like schedules, exhibits come after the main body of the agreement. Though these two terms are often used interchangeably, traditionally an “exhibit” is a pre-existing document or item that is appended to the agreement, as opposed to a schedule, which is created specifically for the purposes of the agreement. Thus, exhibits to a license agreement might include a registration document for the licensed IP, a copy of an existing sublicense or a form of document that the parties will sign in conjunction with the license agreement, such as a promissory note, an assignment, a guaranty or a security interest form.

A Few Notes on Contract Drafting

Part II of this book concerns itself with the drafting of contractual clauses, what they mean, how they vary, and how they have been interpreted by the courts over the years. As such, it is worth spending a few words on the process of contract drafting itself.

Forms and Templates

Today, it is seldom the case that one sits before a blank computer screen to begin drafting a new agreement. Almost all agreements are based, at least in part, on forms, templates and precedents, of which there are vast troves to be found in online databases, law firm files and even the publicly searchable EDGAR database maintained by the Securities and Exchange Commission. One would be foolhardy to attempt to reinvent the wheel with each new agreement. Thus, it is both natural and efficient to rely on prior examples when beginning to draft a new agreement.

Yet, it is also important not to rely too heavily on precedent documents. Every IP licensing transaction other than the most routine consumer-facing nonexclusive licenses is different. The parties have different needs, desires and sensitivities. It is a mistake to assume that the current deal will be exactly like the last deal. Thus, the diligent attorney must approach every agreement clause with care and attention to the specific transaction and client at hand.

Rules versus Standards

In terms of specific drafting advice, it is important always to keep in mind the delicate balance between detail and generality. As one set of commentators aptly explains:

In legislation, treaties, private contracts, and many other dealmaking areas, drafters must make a decision between using a rule or a standard to express meaning. Rules—“deliver the goods on October 1, at 7 p.m. Eastern, unless it is already dark, in which case, deliver the next day”—are more time-consuming to negotiate and draft, but easier to enforce. Standards—“deliver the goods at a reasonable time”—are the opposite: they are easier to draft, but harder to enforce.Footnote 1

No matter how detailed a contract may be, it cannot take into account every eventuality that can arise in the complex hurly-burly of modern business and technology. Thus, do not strain to address every possible eventuality, but become comfortable with broader standards of conduct except where specificity is needed to protect the known interests of your client.

Constructive Ambiguity

Some lawyers feel the urge to specify every detail of a commercial transaction to the nth degree. Detail is, of course, critical in complex commercial arrangements. Delivery schedules, payment amounts, acceptance criteria and myriad other details must be negotiated and recorded in an agreement before it is signed. Failing to do so can, and often does, lead to disagreements down the road.

But not every detail needs to be specified in a contract, particularly when the parties already have a good working relationship. The common law provides a number of flexibilities that enable parties to rely on concepts like reasonable efforts, promptness and good faith as default regimes that can fill gaps in detail that the parties did not reduce to writing at the time of execution. Michal Shur-Ofry and Ofer Tur-Sinai refer to this approach as “constructive ambiguity,” and find that in certain contractual areas and transactions a limited degree of flexibility and ambiguity can be more efficient than the often futile and imperfect attempt to predict every detail that will arise in a complex commercial arrangement.Footnote 2 This said, intentional flexibility is not the same as lazy drafting – some obligations do need to be spelled out in detail, and failing to do so is inadvisable.

Balance

When you, as an attorney, draft an agreement, you are usually doing so on behalf of a client. It is thus natural to draft in a manner that is favorable to your client and a bad idea to draft an agreement that disadvantages your client unnecessarily. That being said, the first draft of an agreement should not be viewed as a declaration of total war. Every clause need not favor your client and disfavor the other party. For example, limitations of liability that only benefit one party, confidentiality provisions that only protect information disclosed by your client, indemnification clauses that only run one way. Any competent lawyer representing the other party will markup these clauses to be more balanced, and may even go further than he or she ordinarily would because of your initial aggressive approach. More importantly, such one-sided agreements seldom serve their purpose or facilitate reaching a mutually acceptable deal. Worse still, I have seen instances in which such a one-sided agreement has triggered a phone call by a business executive on the receiving end to the executives of the well-intentioned attorney’s client. Comments like “your lawyer obviously doesn’t understand this business relationship or the way this industry works” do little to further one’s legal career. In sum, drafting a totally one-sided agreement wastes time, money and goodwill on both sides. A much better approach is to draft a balanced agreement that puts your client’s best foot forward, but does not seek to destroy the other party. Doing so will earn you the respect of both your client and the opposing party and its counsel.

Comprehension

There is no excuse for not understanding the agreement that you have drafted. When a law firm partner or an opposing counsel in a negotiation asks, “what does this clause mean?”, there is no situation in which “I don’t know” is an acceptable response. Nor is it acceptable to respond, “because that clause was in the form that I copied from.” One of the goals of this book is to illuminate many of the types of contractual provisions found in IP licensing agreements. But there are many, many more, and it is up to you, as the drafter of an agreement, to take responsibility for understanding everything that is in it and being capable of explaining it to your co-counsel, your client and the opposing parties.Footnote 3

Precision, Simplicity and Clarity

Words matter. An agreement serves many different purposes and has many different audiences. An agreement memorializes the terms pursuant to which a business transaction is carried out. It will often be read by managers and corporate representatives to guide their conduct. An agreement, particularly an IP licensing agreement, also serves as a legal instrument by which particular rights are granted – an adjunct to the formal grant of rights by the Patent and Trademark Office or which otherwise exists under the law. As such, an agreement is like a promissory note or a debenture – it is a document with independent legal effect that defines valuable asset classes held by different entities. Agreements also define the boundaries of permitted conduct by the parties and, too often, become the subject of disputes. When this happens, the words of agreements are parsed carefully by courts and, sometimes, juries to determine the obligations and liability of the parties.

Each of these scenarios argues for the careful drafting of agreements. But more importantly, they suggest that agreements should be written for a broad audience. The best agreement is one that can easily be comprehended by a lay juror who sees its words displayed on a projection screen in a courtroom. Obscurity generally benefits no one (or at least the party who will benefit cannot easily be predicted).

As a result, clarity in drafting is of paramount importance. Below are a few drafting tips that experienced practitioners abide by:

The fewer words, the better. Don’t use five words when you can use two. Instead of saying “any obligation of any type, nature or kind arising under or pursuant to this Agreement,” you can usually just say “any obligation hereunder.” Don’t say “shall mean” when you can just say “means.”

Be consistent. All agreements have defined terms (see above and Section 13.2). Use them, and use them consistently. If you define “Term” to mean the term of the agreement, use “Term” every time you refer to the term of the agreement, and don’t say “the term of this Agreement” when you just mean “Term.”

Be modular. A good agreement, like a good computer program, is modular in nature. This means that concepts, particularly definitions, should be contained in chunks that refer to one another, rather than spun out in huge paragraphs that are difficult for anyone but the drafter to follow. This is not just a stylistic preference. Modular agreements are much easier to change, both during negotiation and later, if they need to be amended.

Avoid legalese. Always remember that the ultimate audience for your agreement may be a jury of non-lawyers. Most jurors don’t speak Latin. There is simply no need to show off your erudition by using terms like “inter alia” when you can just say “among others.”

IP law is not quantum physics. There are few legal concepts or contractual commitments that a lay person cannot understand, so long as they are expressed clearly and concisely. As you draft agreement clauses, imagine that they will be read by your favorite elderly relative. Will he or she understand what you have drafted, given sufficient interest and patience? If not, consider revising your language.

Trust No One, Proofread, and Don’t be Lazy

Lawyers are busy people, and it is often tempting to cut corners. This is human nature. But there are some circumstances under which you, as a lawyer, should never take shortcuts, and these include ensuring that an agreement that you drafted, negotiated or reviewed accurately reflects the deal that was made, and the intentions of your client. Ultimately, your client is paying you to vouch for the agreement. He or she won’t read it in detail – that is your job, and neglecting to do this can be a career-ending mistake. Take, for example, the unfortunate facts in D.E. Shaw Composite Holdings, L.L.C. v. Terraform Power, LLC (N.Y. Sup. Ct., Dec. 22, 2020), in which one extraneous letter “s” among hundreds of pages of complex M&A documents resulted in a $300 million liability for one party, and a malpractice suit against the law firms that made the mistake.Footnote 4 Or consider PBTM LLC v. Football Northwest, LLC (W.D. Wash. 2021), a case involving the proposed sale of PBTM’s VOLUME 12 and LEGION OF BOOM trademarks to the Seattle Seahawks football franchise. Though negotiations stalled over PBTM’s price for the VOLUME 12 mark, the parties reached a deal on the LEGION OF BOOM mark. The court explains what happened next:

General counsel for the Seahawks drafted a purchase agreement for the trademark, which [the] parties signed on August 24, 2014.

PBTM claims that parties did not discuss the VOLUME 12 mark during negotiations and was therefore “surprised to see later drafts” of the LEGION OF BOOM Agreement that included clauses about VOLUME 12. PBTM claims that it specifically objected to paragraphs 21 and 22 and “wanted them deleted,” since they contained language requiring PBTM to obtain the Seahawks’ consent prior to marketing a BOOM or VOLUME 12 product. However, Seahawks management allegedly insisted that paragraphs 21 and 22 remain but promised to modify the language so that PBTM would not be required to obtain the Seahawks’ consent prior to marketing a BOOM or VOLUME 12 product.

PBTM claims that notwithstanding [the] parties’ discussions about paragraphs 21 and 22, the Seahawks did not revise paragraph 22 to remove the mandatory consent provision. PBTM alleges that as a result of pressure from Seahawks management to immediately sign the agreement, and because [the] parties previously had a cordial working relationship, PBTM only gave the execution version a “cursory review.” Consequently, it failed to notice that paragraph 22 was not revised as PBTM requested …

Shortly after signing, PBTM discovered that the Seahawks had omitted the language PBTM requested in paragraph 22 to make the Seahawks’ consent non-mandatory, and PBTM “promptly protested this omission several times.” Although the Seahawks reassured PBTM that its general counsel would add the “not mandatory” language to paragraph 22 to make the consent provision non-obligatory, the language was never added and the Seahawks have since refused to do so.

When PBTM finally brought an action for contract reformation on the basis of unilateral mistake, the statute of limitations had run. And even if it had not, it is not clear that such an action would have been successful.

The moral of this story? Don’t trust opposing counsel to make “agreed” changes to a draft agreement without checking that they were actually made. Better still, don’t trust anyone to do your work without checking that it was done. Ultimately, you, as an attorney, will be held responsible for mistakes such as these, and the facts recited above would not play well in a legal malpractice action or a bar disciplinary proceeding.

Summary Contents

The license grant is the heart of any intellectual property (IP) license. This chapter explores many of the issues that arise in defining what rights are granted under a license agreement.

6.1 Licensed Rights

One of the most fundamental things that every license agreement must define is the set of rights that are being licensed. This definition must answer two related questions: what type of rights are being licensed (e.g., patents, copyrights, trademarks, etc.), and which of those rights are being licensed (e.g., which of the licensor’s patents, copyrights, trademarks, etc.)? Though this exercise may sound straightforward, there are many ways that licensed rights can be identified, with significant ramifications for both the licensor and licensee. (Note that the definition of licensed rights is often tailored to the type of IP being licensed, so that a patent license agreement might refer to “Licensed Patents” instead of “Licensed Rights” and a trademark license may refer to “Licensed Trademarks,” “Licensed Marks,” “Licensed Brands” or some other variant.)

6.1.1 Enumerated Rights

One way to identify licensed rights is by enumerating those rights specifically and individually. Such an enumeration can refer to the governmental registrations for those rights, such as patent, trademark and copyright registrations. If there are too many rights to list conveniently in the text of a definition, a separate list can be attached as an exhibit to the agreement. Here is a simple example involving registered trademarks.

Single Registered Mark

“Licensed Mark” means U.S. Trademark Reg. No. 999,999 “SUPER-BEV”.

Multiple Registered Marks

“Licensed Marks” means those U.S. and foreign trademark registrations listed in Exhibit A to this Agreement.

Unregistered IP can also be enumerated, so long as it can be described in a manner that clearly identifies and distinguishes it. Thus, unregistered (common law) trademarks can be included as part of a license grant, as can unregistered copyrights and even inventions and trade secrets that are not (yet) subject to any patent application. Some examples include the following.

Enumerated Rights Including Unregistered IP

“Licensed Marks” means those Marks that are listed in Exhibit A to this Agreement.

“Marks” means trademarks, service marks and designs, whether or not registered.

“Licensed Rights” means all Authorship Rights throughout the world subsisting in the work THE GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL by Author.

“Authorship Rights” means copyrights and related rights of authors, including moral rights.

“Licensed Rights” means all Know-How in Licensor’s proprietary method for curing rubber utilizing heat modulation calibrated using the Arrhenius equation, as described in the confidential specification delivered by Licensor to Licensee on October 31, 2020.

“Know-How” means all know-how, trade secrets, discoveries, inventions, data, specifications and other information [, including biological, chemical, pharmacological, toxicological, pharmaceutical, analytical, safety, manufacturing and quality control data and information, study designs, protocols, assays and clinical data], whether or not confidential, proprietary or patentable and whether in written, electronic or any other form.Footnote 5

Drafting Note

The above definitions include both a generic definition of the category of IP, as well as a definition of the licensed IP that incorporates the generic category. Using this modular structure in all but the simplest licensing agreements is advisable, as the generic IP category may be referred to elsewhere in the agreement (e.g., in the indemnification section) and it is best to use consistent terminology throughout.

Patents pose some additional issues. Like trademarks, patents are registered (and there are no common law patent rights analogous to common law trademarks). Yet many different patents may relate to the same basic invention. That is, during the patent prosecution process, patent applications may be subdivided, amended, continued and extended through a variety of different procedural mechanisms. Thus, one invention can end up being claimed by a dozen different patents that are issued for years following the issuance of the initial patent. Foreign patent applications can also be filed in multiple countries under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) based on an original application in one country. These groups of related patents are often called a “patent family,” and licensing is often conducted at the family level rather than the level of individual patents. The unifying trait of a patent family is often the ability to trace the origin of a patent to a single “ancestor” application filed on a date that is known as the “priority date” for the family and its other members. Figure 6.1 illustrates the different members of such a patent family. An example of a patent family definition follows.

Figure 6.1 Graphical representation of a patent “family.”

Licensed Patents as Single Patent Family

“Licensed Patents” means U.S. Patent No. x,xxx,xxx entitled “Improved Method for Slicing Bread and Apparatus Therefor” (September 9, 1999), together with all Patents claiming the same priority as such patent. [1]

“Patents” means (a) patents and patent applications [4], and all divisional, continuation, and continuation-in-part applications of any such patent applications; (b) all patents issuing from any of the foregoing applications; and (c) all reissues, reexaminations, extensions, foreign counterparts [2] and supplementary protection certificates [3] of any of the patents described in clauses (a) or (b).

Drafting Notes

[1] Priority – the “priority date” of a patent is the date on which the earliest utility patent application in the “family” of related applications was filed.

[2] Foreign counterparts – this term refers to foreign patents and patent applications, often filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty, that derive from the same parent application.

[3] Supplementary protection certificates – these are European rights that protect certain pharmaceutical and other regulated compositions after their patent protection has expired.

[4] Applications – even though patent applications convey no enforceable rights, they can, and often are, licensed. Doing so is a convenient way to ensure that any patent rights that eventually emerge from such applications are licensed. The alternative would be to require the licensor to be extremely diligent in adding patents to the license grant as they are issued, a responsibility that benefits neither party.

The following case illustrates the importance of including the “right” rights in a license agreement.

Spindelfabrik Suessen-Schurr Stahlecker & Grill v. Schubert & Salzer Maschinenfabrik Aktiengesellschaft

829 F.2d 1075 (Fed. Cir. 1987)

BALDWIN, SENIOR CIRCUIT JUDGE

In 1983, Suessen, brought an action in the district court for infringement of two patents relating to improvements in the technology of open-end spinning devices, U.S. Patent No. 4,059,946 (the ’946 patent) and U.S. Patent No. 4,175,370 (the ’370 patent).

Schubert argues that it has an implied license under the ’946 patent. Its argument involves two agreements.

The first was a license agreement entered in 1982 between Schubert and Murata Machinery, Ltd. (Murata). That agreement, entered into before the filing of this suit in 1983, in pertinent part reads:

Murata hereby grants to Licensee [Schubert] a non-exclusive worldwide license under the Patents to make, use and sell the patented device only as part of the open end spinning machines of the License. The License hereby granted is a limited license, and Murata reserves all rights not expressly granted.

The “Patents” were defined [to] include U.S. Patent No. 4,022,011 (’011 patent) and other patents belonging to Murata in the name of Hironorai Hirai. Schubert asserts that, notwithstanding any infringement of ’946, its accused infringement is merely a practicing of the ’011 invention, which it is licensed to do under the 1982 agreement.

The second agreement, entered in 1984 after this lawsuit began, involved Suessen’s purchase of the ’011 and [other] patents from Murata. The agreement reads, in pertinent part:

Suessen has been advised by Murata that a non-exclusive license of the patents and patent applications mentioned under 1. above had been granted by Murata to [Schubert] (hereinafter called the Licensee). Suessen hereby agrees to purchase the patents and patent applications mentioned under 1. above together with the License Agreement as of 23rd/28th July, 1982, with the said Licensee and agrees that you and your business/license concerns will maintain the licensed rights of the Licensee under the License Agreement as stipulated during the life of the patents and patent applications mentioned under 1. above.

Schubert asserts that, per the 1984 agreement, Suessen “stepped in the shoes of Murata” [and] cannot – just as Murata cannot – sue under the ’946 or any other patent for infringement based on practicing the ’011 invention. To allow such a suit, Schubert argues, would unfairly take away what it paid for in 1982. Schubert labels its argument one of “legal estoppel.”

[Schubert] asserts an implied license based on its theory of legal estoppel. Though we recognize that theory in appropriate circumstances, it does not work for Schubert here. Legal estoppel is merely shorthand for saying that a grantor of a property right or interest cannot derogate from the right granted by his own subsequent acts. The rationale for that is to estop the grantor from taking back that for which he received consideration. Here, however, we have a suit by a third party, Suessen, under a patent owned by Suessen. The license by the grantor, Murata, did not purport to, and indeed could not, protect Schubert from a suit by Suessen under ’946. Hence, Suessen, by filing in 1983 and now maintaining its suit under ’946, does not derogate from the right given by Murata in the 1982 license agreement.

Figure 6.2 Ownership and license of ’011 and ’946 patents in Spindelfabrik.

Schubert nevertheless urges this three prong argument: (1) “legal estoppel” would prevent Murata from suing under the ’946 patent if it were to acquire it; (2) Suessen “stepped into” Murata’s shoes in 1984 when Suessen acquired the Hirai patents and committed to maintain Schubert’s licensed rights; and hence, (3) just as Murata could not, Suessen cannot sue under the ’946 patent. We reject that argument.

As a threshold matter, a patent license agreement is in essence nothing more than a promise by the licensor not to sue the licensee. Even if couched in terms of “[l]icensee is given the right to make, use, or sell X,” the agreement cannot convey that absolute right because not even the patentee of X is given that right. His right is merely one to exclude others from making, using or selling X. Indeed, the patentee of X and his licensee, when making, using, or selling X, can be subject to suit under other patents. In any event, patent license agreements can be written to convey different scopes of promises not to sue, e.g., a promise not to sue under a specific patent or, more broadly, a promise not to sue under any patent the licensor now has or may acquire in the future.

As stated previously, the first prong of Schubert’s three part “stepping in the shoes” argument is that legal estoppel would prevent Murata from suing Schubert under the ’946 patent if Murata were to acquire that patent. However, even assuming, arguendo, that such estoppel against Murata exists, the final two prongs of Schubert’s “stepping in the shoes” argument would fail. Given the assumption of estoppel against Murata, the 1982 license agreement would necessarily be a promise by Murata not to sue under any patent, including those acquired by Murata in the future. In the 1984 agreement, Suessen incurred what Murata promised in 1982. Thus, Suessen would be committed to forebear from suit under (1) the transferred patents and (2) any of Murata’s nontransferred patents (future and present). That commitment does not include a promise not to sue under Suessen’s own ’946 patent.

Schubert’s “standing in the shoes” argument, however, would add to Suessen’s commitment a promise not to sue under Suessen’s separate patents that Murata never owned. On the facts of this case, we cannot interpret the 1984 agreement so broadly, at least not with respect to the ’946 patent.

The district court correctly determined that there is nothing in the 1984 agreement about the ’946 or other Suessen patent rights. Schubert points to no extraneous evidence tending to show any understanding on the part of either contracting party that Suessen was to forego rights under the ’946 or any other patent then owned by Suessen. To the contrary, that a lawsuit under ’946 was ongoing but not mentioned in the 1984 agreement indicates strongly that there was no intent by the parties to have Suessen forfeit its rights under ’946. Furthermore, an implied promise by Suessen to forego its ’946 suit is inconsistent not only with Suessen maintaining its lawsuit after the 1984 agreement but, also, with the course of events leading up to the 1984 contract. In sum, we agree with the district court’s conclusion that the 1984 agreement did not impose on Suessen any obligation to stop its ongoing suit under the ’946 patent.

Schubert argues that not implying a license in this case is unfair because Schubert paid valuable consideration for the right to practice the ’011 invention but is in danger of losing that right as a result of doing no more than that for which it paid. We disagree. The right Schubert paid for in the 1982 agreement was freedom from suit by Murata, not Suessen. Indeed, when Schubert signed the 1982 agreement, it was aware of possible suit by Suessen, who had previously denied Schubert a license under the ’946 patent. Moreover, Schubert has not shown us that it has lost any obligation Murata may still owe it under the 1982 license agreement, e.g., not to sue under any patents Murata still has or may acquire. To rule that the Suessen acquisition of the ’011 patent somehow bestows on Schubert an absolute defense to a suit already filed by Suessen under ’946, would result in an unintended windfall to Schubert that makes no sense under the facts of this case.

AFFIRMED

Notes and Questions

1. Implied licenses. In Chapter 4 we saw several examples in which courts implied licenses based on the conduct of the parties. How is Spindelfabrik different than these cases? If you were the judge, would you have recognized an implied license from Suessen to Schubert?

2. Patent families. How might the patent family definition suggested above have helped the parties in the TransCore and Endo cases discussed in Section 4.3, Notes 3–4?

3. The importance of timing? In Spindelfabrik, under the 1982 agreement, Murata licensed the ’011 patent to Schubert. In 1984, Murata assigned the ’011 patent and Schubert’s license to Suessen. Prior to that, Suessen asserted the ’946 patent against Schubert. The court held that nothing about Suessen’s purchase of the ’011 patent and license committed it to license the ’946 patent to Schubert. But what if Suessen had purchased the ’011 patent and license before it asserted the ’946 patent against Schubert? Would this have changed the outcome? What if the ’946 patent had originally been owned by Murata, but not included in the 1982 agreement, and then assigned to Suessen at the same time as the ’011 patent? Would Schubert’s estoppel argument be stronger?

4. Products versus patents. The Spindelfabrik case is really about product versus rights licenses (see the box “Rights Licenses versus Product Licenses”). Schubert argues that because it licensed the ’011 patent, it had an absolute right to manufacture the product covered by the ’011 patent. But it did not. The licensee of a patent only has the right to operate under the licensed patent and no more. How might the license agreement have been written to achieve what Schubert hoped, or assumed, it had achieved?

6.1.2 Portfolio Rights

Defining licensed rights by reference to a specific registered (or unregistered) IP right and its associated family members is relatively precise and avoids ambiguities regarding what is and is not licensed. Yet enumerating individual licensed rights can be both an administrative burden and a trap for the unwary. Suppose that a licensee wishes to obtain a license not to one, but a thousand different patents covering a complex product such as a smartphone or a computer. If the licensor were required to list every one of the licensed patents, it is possible that one or more patents might be overlooked. And, given cases like Spindelfabrik, it is difficult to argue that a right that is not enumerated in a list of licensed IP should be included in a license.

To get around this problem, parties have developed language under which groups of IP rights can be licensed without enumerating every one of them. Below is an example of such a “portfolio.”

Patent Portfolio

“Licensed Patents” means all Patents throughout the Territory that are Controlled by Licensor or any of its Affiliates at any time during the Term [1] and that (a) claim all or any part of Licensor’s Super-Slicer bread slicing device, or the use thereof [2], and (b) have a priority date earlier than January 1, 2021 [3].

“Control” means with respect to any intellectual property right, possession of the power and right to grant a license, sublicense, or other right to or under such intellectual property right as provided for in this Agreement without violating the terms of any agreement or other arrangement with any third party [4].

Drafting Notes

[1] Temporal portfolio constraint – this clause applies to every patent that is in the licensor’s portfolio during the term, including patents that the licensor acquires after the effective date of the agreement. If the parties wish to limit the portfolio to patents held as of the effective date, “during the Term” can be changed to “prior to the Effective Date.”

[2] Portfolio scope – the above definition is said to cover the licensor’s portfolio of patents pertaining to a particular device. If the licensor wishes instead to grant a license of its entire patent portfolio, then clause (a) would be eliminated.

[3] Cutoff date – clause (b) serves to exclude new inventions from a portfolio license. This approach can be useful if, for example, the license fee is paid in a lump sum (as it may be in a settlement agreement – see Section 11.6) based on the value of the licensor’s existing patent portfolio. Note that the cutoff date in clause (b) may be prior to or after the effective date of the agreement itself and would not exclude newly acquired patents so long as they meet the cutoff date.

[4] Third-party licenses – the definition of control is intended to encompass rights that the licensor owns or otherwise has the power to license. If it has already granted an exclusive license with respect to a right, then it cannot license it again (see Section 7.2.1), so such rights are not included in the license. Of course, a licensee that is concerned about such exclusions (e.g., the Swiss cheese effect) should insist that the licensor make representations and warranties (see Chapter 10.1) regarding the scope of the portfolio that is licensed and any exclusive licenses that could potentially remove necessary IP from the rights granted.

Notes and Questions

1. Which portfolio? In the patent portfolio definition set forth above, the licensed portfolio is defined by reference to a specific product sold by the licensor. Are there other ways that you could define a licensed portfolio? When might a licensor wish to grant a licensee a license with respect to its entire portfolio of patents?

2. Cutoff date. In the patent portfolio definition, there is a cutoff date beyond which patents controlled by the licensor are not included in the license. Would such a cutoff date ever be useful in a license in which the licensed rights are specifically enumerated? The cutoff date in clause (b) may be prior to or after the date of the agreement itself – when would it be useful to have a cutoff date that is after the date of the license agreement?

3. Control. In order to be licensed, patents (and other IP rights) must be owned or controlled by the licensor. This is the principal reason that Schubert’s claim failed in Spindelfabrik – Murata could not license the ’946 patent to Schubert because Murata did not own that patent. Accordingly, the patent portfolio definition set forth above defines licensed patents as those that are owned or controlled by the licensor or its corporate affiliates (see Note 4). Why is this language not needed when the licensed rights are enumerated specifically?

4. Affiliates. The term “Affiliates” is often used in licensing agreements to signify the other members of a party’s corporate “family” – parent, subsidiary and sibling entities. Including IP held by affiliates in definitions such as the licensed rights is important, as large multinational organizations often hold or exploit IP rights in various entities for tax and accounting purposes. It is common to define “Affiliates” using the definition provided under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934:

An “affiliate” of, or a person “affiliated” with, a specified person, is a person that directly, or indirectly through one or more intermediaries, controls, or is controlled by, or is under common control with, the person specified.

The term “control” (including the terms “controlling,” “controlled by” and “under common control with”) means the possession, direct or indirect, of the power to direct or cause the direction of the management and policies of a person, whether through the ownership of voting securities, by contract, or otherwise.

Under this definition, “control” typically means ownership of at least 50 percent of the voting securities or interests of an entity.Footnote 6 As such, majority-owned subsidiaries of an entity are included within the definition of “Affiliates.” Can you think of any reasons that the parties might prefer to define “control” as the ownership of 100 percent of the voting securities or interests of an entity (e.g., limited to wholly owned subsidiaries only)?

Figure 6.3 Affiliate relationships in a corporate “family.”

There are several contexts in which it is particularly important to pay careful attention to rights and IP held by affiliates:

Alpha grants Beta an exclusive license under “all of Alpha’s and its Affiliates’ IP covering technology x”; Alpha is then acquired by Gamma, a larger company that also works in technology x. Does the license now cover Gamma’s IP as well? What if the license was paid-up at the time of grant?

Instead, assume that Alpha’s subsidiary Delta also holds IP relating to technology x, and Alpha then sells Delta to Epsilon. Is Delta’s IP still licensed to Beta? Is Epsilon’s?

Now suppose that Beta has granted a license under its own IP to Alpha and its affiliates. Alpha sells Delta to Epsilon. Does Beta’s license to Delta continue once it is owned by Epsilon? Does Epsilon now get a license under Beta’s IP? Again, what if all of these licenses were paid-up at the time of grant?

Can you think of more scenarios in which the extent of corporate families can play an important role in IP transactions?

5. IP divestitures. As discussed in Chapter 3.5, licenses of IP rights generally continue even if the underlying IP right is sold by the licensor. Thus, when a licensor grants a portfolio license and then sells some of the IP rights in the portfolio, the licensee can generally rely on the continuation of that license, and the buyer (or even a new exclusive licensee) takes subject to the earlier-granted license. If this is the case, then in Spindelfabrik why did Murata assign the 1982 license agreement with Schubert to Suessen when Murata sold the ’011 patent to Suessen?

6. Copyright (and trademark) portfolios. Portfolio licenses are not limited to patents. In many cases, copyrights are licensed on a portfolio basis as well. For example, a television network may license all of its programming to a cable provider or online streaming service, and a performing rights organization such as ASCAP or BMI routinely licenses thousands of songs to its licensees for particular uses (see Chapter 16). Trademarks, however, are not typically licensed on a portfolio basis, but are usually enumerated, even if a large number of marks are being licensed. Why?

6.1.3 The Puzzle of “Know-How” Licensing

License agreements involving technology often include a grant of rights with respect to “know-how.” What is “know-how”? It is not a recognized form of IP. Though it may encompass trade secrets, know-how is generally understood to be broader than trade secrets alone. Noted organizational theorist Eric von Hippel defines know-how as “the accumulated practical skill or expertise which allows one to do something smoothly and efficiently.”Footnote 7 J. N. Behrman, who conducted some of the first empirical studies of IP licensing in the United States, defines it as:

whatever unpatented or unpatentable information the licensor has developed and which the licensee cannot readily obtain on his own and is willing to pay for under the agreement; such as techniques and processes, the trade secrets necessary to make and sell a patented (or other) item in the most efficient manner, designs, blueprints, plant layouts, engineering specifications, product mixes, secret formulas, etc.Footnote 8

Unlike know-how, trade secrets are recognized IP rights protected in the United States by federal and state statutes as well as common law. As discussed in Chapter 5.2, in order to be considered a trade secret, information must derive independent value from being kept secret and must be the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain confidentiality. These requirements are not always easy to establish, and information that is conveyed during the course of technical training, product demonstrations and support calls may not always qualify as trade secrets, despite its value to the recipient.

The concept of “know-how” has thus evolved to include both trade secrets as well as other information that is conveyed by the licensor to the licensee. So long as information is conveyed – whether orally, visually or in writing – it can be “know-how.” This lower bar is useful primarily to establish a basis for the payment of ongoing royalties with respect to the information conveyed. That is, if a license covered only trade secrets, and the information in question lost trade secret status for some reason, then it is unclear that the license would remain in effect or that the licensee would have a continuing obligation to pay royalties. But if the royalty were payable instead on know-how, then the loss of trade secret status with respect to some or all of that information would not affect the license or the obligation to pay royalties. Thus, know-how is a more flexible concept than trade secrets, supporting a stronger basis for the payment of royalties.

However it is defined, know-how is frequently featured in license agreements. As early as 1959, a study of more than 1,000 IP license agreements found that approximately 39 percent included grants of know-how rights.Footnote 9 More recently, Thomas Varner, in a study of over 1,400 publicly filed patent licenses and assignments, found that 56 percent included know-how.Footnote 10 So we know that know-how is being licensed, but what does this mean in practice?

There are two principal functions that know-how licensing plays in IP transactions. The first is straightforward. If the licensor provides training, support, consultation, expertise or some other technical services to the licensee, then the information and skills conveyed through those services are “licensed” as know-how. Even though most of this intangible knowledge is not protected (or even protectable) by formal IP rights, courts have long recognized that such information can be valuable and thus the subject of compensation.

In many cases, however, no such knowledge transfer is contemplated, yet the license agreement (usually a patent license agreement) still contains a license of know-how. In these cases, the know-how license is included simply as a clever way for the licensor to continue to collect royalties after the relevant patents expire. As we will see in Chapter 24, it is illegal under US law for a patent holder to continue to collect royalties for the use of a patented technology after the patent has expired. To get around this limitation, patent holders can license patents and know-how together, so that even after the patents expire, there is still a valuable asset to support the payment of royalties (albeit at a reduced level). The same logic applies to patents that are invalidated after being licensed, and to sales of products in countries where the patent holder does not seek patent protection. In all of these cases, royalties can be collected with respect to know-how, even though no enforceable patents are licensed.

Combined Patent and Know-How Definition

“Licensed Rights” means the Licensed Patents and all associated Know-How conveyed by the Licensor to the Licensee hereunder.

“Know-How” means trade secrets, knowledge, techniques, methods and other information, whether or not patentable.

Notes and Questions

1. The risks of know-how licensing? In the 1950s and 1960s there was significant concern among scholars and policy makers that the licensing of vaguely defined know-how might run afoul of antitrust laws.Footnote 11 We will study antitrust issues arising in connection with licensing transactions in Chapter 25, but for now it is sufficient to understand that “licenses” of this amorphous set of rights were viewed as a potential cover-up for otherwise anticompetitive arrangements. What kind of anticompetitive behavior do you think a know-how license might conceal?

2. Know-how licensing and patent trolling. Professors Robin Feldman and Mark Lemley have observed that when a patent holder makes an unsolicited licensing proposal to a potential licensee (e.g., as a prelude to an express or tacit threat of litigation), the resulting licenses seldom include a transfer of know-how.Footnote 12 This result held whether the patent holder was a non-practicing entity, a university or a company. Professor Colleen Chien, in contrast, found in a study of publicly filed licenses of software patents that most patent licenses also included a license of know-how or software code.Footnote 13 She explains the difference between her results and those of Feldman and Lemley as follows:

Patent licenses that include knowledge, know-how, personnel, or joint venture relationships are more likely to represent direct transfers of technology, whereas the transfer of “naked” patent rights is more likely to primarily represent a transfer of liability between the parties.Footnote 14

What does Chien mean by a “transfer of liability between the parties”? Why would know-how transfers be more frequent in a broad sampling of licensing transactions than patent-owner-initiated demands for a license?

3. Taxing know-how. In addition to antitrust, early concerns over know-how licensing arose from tax law. Was know-how a taxable asset, or was the transfer of know-how a service? In each case, how was it valued? Together with “goodwill” (see Chapter 2.4), know-how presents one of the more interesting tax issues in the field of IP licensing.Footnote 15

6.1.4 Product Rights

So far, our consideration of licensed rights has focused on specific IP rights or groups of rights that the parties desire to license. This approach is natural when particular patents, copyrights, trademarks or trade secrets are known, or expected, to have value in themselves. However, it is often the case that a licensee is interested in exploiting a product that may be covered by a variety of IP rights held by the licensor, and neither the licensor nor the licensee knows, or particularly cares, which rights those may be.

Software programs often fall into this category. Software can be protected by large numbers of copyrights, patents, trade secrets, trade dress, trademarks and other forms of IP. But if a distributor wishes to resell a software program via an online store, or a consumer wishes to use that software on her laptop computer, it is unlikely that they are aware of, or have any desire to know about, the specific IP rights covering that software. In fact, in many cases, even the owner of the software, particularly if it is a large company, may not be aware of the many different IP rights that protect it. Thus, in software and other industries, the common practice is to license all rights pertaining to a particular product without any attempt to list or even categorize them.

Product License Rights

The term “Licensed Software” means the executable object code of the SOFTMICRO application (version 1.0) and all of Licensor’s patent, copyright, trade secret, trade dress and other rights in and to such software application and its operation, but excluding trademarks.

In some cases, a licensor granting a license with respect to a full product, especially a software product, will not even recite the IP rights that are licensed at all, and will simply grant the license in the Grant clause of the agreement (see Section 6.3). Or, if it separately defines the licensed software, it will omit to mention any IP rights.

Product License Rights: Simplified

The term “Licensed Software” means the executable object code of the SOFTMICRO application (version 1.0).

Rights Licenses versus Product Licenses

There is a critical difference between licenses of rights and licenses of products. In a license of rights, for example a patent license, the licensee is permitted to create and exploit any product that it wishes within the bounds of the license grant (e.g., within the field of use and scope of license discussed in Section 6.2). Thus, if the licensed patent covers an amplifier, the licensee may make any amplifier that it wishes – large, small, low-power, portable, transistorized, heat-resistant, etc. In short, it may use the patented technology to create a product of its own. In contrast, a product license allows the licensee to make only the exact product that is licensed. Thus, if Microsoft licenses its Windows operating system to a PC manufacturer, the licensee is likely permitted to install Windows on its PCs, but not to create a new, improved version of Windows or any other operating system. This key difference is important to keep in mind when reviewing the many variants of license agreements that will be discussed in this book.

Notes and Questions

1. Code. The sample definition of “Licensed Software” relates to the “object code” version of the software. We will discuss the distinction between object code and source code in more detail in Section 18.2. For now, it is sufficient to understand that the object code version of software is the version that runs on a user’s computer or device, but does not allow the user to understand the internal functions of the software or how it is “written.” Why do you think most software distribution and use licenses are limited to object code?

2. No trademarks. Trademark rights are typically excluded from a product-based license or, if granted, are licensed separately. There are several reasons for this convention. First, a trademark license is not required to use a software program, even if the program displays the vendor’s trademarks (we will discuss trademark licensing in greater detail in Chapter 15). A distributor or reseller may require a license to advertise a software program, but that license will contain numerous qualifications and requirements and is thus best granted separately from the right to distribute the program. Finally, doctrines in trademark law such as “nominative fair use” permit parties to refer to a trademarked term in a factual manner (e.g., “We service BMW vehicles”), without the need for a formal license. As a result, a well-drafted definition of product rights should generally exclude trademarks.

6.1.5 Future Rights

It is a somewhat metaphysical question whether an IP right can actually be “licensed” before it is created. Is the license of a future IP right – a patent claiming an invention not yet made, the copyright in a book not yet written – a property interest that exists independent of the right itself, like a contingent remainder or other future interest in real property, or is it merely a promise to license the IP right once it exists? This is a question that deserves to be debated in the law reviews, but is not one that we will answer here. For all practical purposes, as we saw in Stanford v. Roche (Chapter 2.3), interests in IP that is not yet created can clearly be bought, sold and licensed. Yet, as that case also suggests, there is an important difference between a present license of future inventions and a promise to grant a license in the future (with the former clearly preferable to the latter).

In fact, we have already seen licenses of future rights above, in our example of a patent portfolio license. If, during the term of the license, the licensor comes into possession of a new patent that meets the other criteria for a licensed right, then that new patent is licensed along with the rest. But future rights may be licensed more explicitly, and they often are.

Future Licensed Rights

“Licensed Work” means the book that is written and delivered by Author hereunder, currently known under the working title THE GREAT AMERICAN NOVEL.

“Licensed Rights” means all patent, copyright, know-how, trade secret and other rights in all developments, inventions and discoveries in the Field made by Dr. Jekyll and the other members of the Jekyll Lab at Stevenson University during the Term.

Problem 6.1

For each of the following deals, draft a suitable definition of the “Licensed Rights”:

a. Transatlantic Corp. has agreed to sell its fleet of Atlantic fishing vessels to United Fishfry. After the sale, Transatlantic will continue to operate its remaining fleet of seven passenger cruise ships. Several years ago, Transatlantic developed a patented method of radar enhancement that greatly improves navigation at sea. The enhancement is now used on all of Transatlantic’s ships. The parties have agreed that, as part of the fleet sale, Transatlantic will grant an appropriate license to United.

b. Lobrow Corp. sells a popular line of children’s toys in the United States based on the popular YouTube character “Bo Weevil.” Assume that Lobrow owns all rights in and to this character and has protected it around the world. In an effort to go international, Lobrow has agreed to grant Downunder, Inc. the right to distribute Bo Weevil toys in Australia and New Zealand.

c. Don Juan has just published a bestselling memoir of his scandalous career in Hollywood. He was recently approached by RealTV, a producer, to develop the memoir into a Netflix television series.

d. Choco Corp. and PeaNot, Inc. are large snack food manufacturers. They have formed a joint venture (JV) to create and market a candy bar that combines the best features of each of their existing product lines (chocolate bars and synthetic peanuts). Each of them will receive 50 percent of the profits of the JV during its existence and has agreed to grant a license to the JV.

6.2 Scope of the License: Field of Use, Licensed Products, and Territory

Once the licensed IP rights are defined, we must define the markets and applications in which the licensee will be permitted to exploit those rights. In some rare cases, a licensor may wish to cede all potential markets and applications of its IP to the licensee throughout the world. If this is the case, then these concepts can simply be incorporated into the grant clause, discussed in Section 6.3. However, if the licensor wishes to grant the licensee only a subset of the total rights available, then careful attention must be paid to defining the scope of the licensee’s use. Three related definitions are often employed for this purpose: Field of Use, Licensed Products and Territory. While different agreements may combine some or all of these definitions, we will discuss each individually before considering how they can be combined.

6.2.1 Field of Use

The field of use (FOU) is the market segment or product category in which the licensee is authorized to exercise the licensed rights. There is a virtually unlimited range of fields that can be specified in an agreement, from extremely narrow to extremely broad. Following are examples of FOU for three different types of IP.

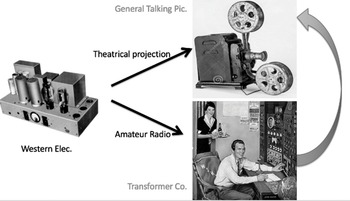

The limitation of a patent licensee’s FOU was validated by the Supreme Court in General Talking Pictures Corp. v. Western Electric, 304 U.S. 175 (1938). In that case, Western Electric, the holder of a patent on electronic amplifiers, licensed the patent to two different licensees: Transformer Co., in the field of amateur radio, and General Talking Pictures, in the field of movie projectors. When Transformer Co. began to sell amplifiers to General Talking Pictures for use in its projectors, Western Electric sued, alleging that Transformer Co. was not licensed to sell amplifiers for use in the theatrical projection market, and was thus infringing Western Electric’s patent. The Supreme Court agreed, holding that “patent owners may grant licenses extending to all uses or limited use in a defined field.”

Fields of use come in two flavors: those that limit the technical application of a licensed right (e.g., “treating emphysema”) and those that limit the customers to which products may be sold (e.g., manufacturers of amateur radio receivers versus movie projectors). In some respects, these two categories can appear to merge, as types of customers are easily defined by different technical applications (and the explicit allocation of customers is a violation of the antitrust laws – see Section 25.3). Nevertheless, analytically it is sometimes convenient to think of FOU as limiting either technical applications or customers.

Some agreements may define multiple fields of use: a licensee may have exclusive rights in some fields and nonexclusive rights in other fields; some fields may be prohibited to it; and it may have the option to acquire rights in still other fields, often upon the payment of a fee.

Field of Use Examples

Biotech (e.g., a new molecule)

Treatment of hereditary breast cancer using a therapeutic agent targeted to variants in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes;

treatment of hereditary breast cancer using a therapeutic agent targeted to one or more genetic variants;

treatment of hereditary breast cancer;

treatment of breast cancer;

treatment of cancer;

human therapeutics;

all therapeutic applications, human and veterinary;

all applications, whether therapeutic, diagnostic, agricultural, industrial or military.

Electronics (e.g., part of a 5G telecommunications standard)

Implementation of wideband wireless communication functionality conforming to the 5G standard in a consumer handheld smartphone device;

implementation of wideband wireless communication functionality in a consumer handheld smartphone device;

implementation of wideband wireless communication functionality in a consumer device;

implementation of wideband wireless communication functionality in a communications device;

implementation of wireless communication functionality;

communications applications;

all applications.

Literary (e.g., a popular novel)

English-language print books for the US and Canadian market;

Spanish-language editions;

paperback editions;

ebooks;

magazine serializations;

audiobooks;

stage plays;

television and film adaptations;

action figures and other memorabilia;

T-shirts and other apparel;

theme park attractions.

Notes and Questions

1. Going broad. Generally, a licensee will desire an FOU that is as broad as possible, while the licensor will seek to limit the FOU so that it retains as many rights as possible to grant to others or exploit itself. Under what circumstances might a licensee be concerned about an FOU that is too broad?

2. Biotech FOU. In some industries, particularly biotechnology, there may be multiple potential uses for a licensed compound, such as a molecule, protein or gene. It is thus not uncommon in biotech licenses to see FOU that are limited to specific disease targets (e.g., cancer, cystic fibrosis, diabetes) or delivery mechanisms (e.g., intravenous, oral, topical, gene therapy). In many cases, license grants are exclusive with respect to these narrowly specified FOU. These licenses are typically granted at early stages of product research and development.

However, once a relatively complete drug or therapy is licensed (e.g., from a biotech company to a pharmaceutical manufacturer that will seek regulatory approval and then manufacture and market the drug), it is not typical to limit use by disease indication. The reason is that physicians are generally free to prescribe a medication for any use (i.e., the indicated use as well as “off label” uses), and the distributing company has little means of policing whether those uses fall within the scope of its license.

3. Anticompetitive fields? In General Talking Pictures, discussed above, Justice Black dissented, expressing concern that the allocation of different “fields” to different patent licensees, especially if numerous patents held by different owners were pooled together, could have the effect of creating a series of submonopolies that limited competition. We will discuss antitrust issues in greater detail in Chapter 25, but based on what you now know about FOU, do you agree with Justice Black’s concern?

4. FOU and the lawyer’s role. The FOU definition is one of the few parts of a license agreement that does not depend on legal terminology so much as a deep and accurate understanding of the licensed rights, the market and the potential business relationship between the parties. Clients will often provide their attorneys with a definition of the FOU that they feel is adequate, and that definition may even be embedded in a term sheet or letter of intent before the license drafting begins (see Section 5.3). But the diligent attorney should consider whether there are unanticipated pitfalls in the client’s FOU definition: Is it too broad or too narrow? Will it enable the licensee to carry out the business arrangement that is anticipated? How will it fare in the face of competition from others? Will the licensor have sufficient flexibility to license others in adjacent fields? Will the definition quickly become obsolete as technology advances? Asking questions like these, rather than cutting and pasting an FOU definition from a client’s email or term sheet, will serve the interests of both parties to the transaction.

Problem 6.2

For each of the following IP rights, describe the broadest FOU that you would realistically wish to obtain as the licensee, and the narrowest FOU that you would realistically wish to grant as the licensor:

a. a patented synthetic molecule that converts petroleum products into refined sugar;

b. the #1 R&B hit song “Bag of Fleas” by the megagroup Shag Shaggy Dog;

c. a little-known Bulgarian superhero comic character known as “Tarantula Man”;

d. a patented software encryption methodology that would reduce the effectiveness of cyberattacks by 90 percent;

e. the world-famous “squish” brand/logo that Squish Corp. has popularized through a line of high-end sports footwear;

f. The persona of the recently deceased pop superstar formerly known as Princess.

6.2.2 Licensed Product

The term “Licensed Product” means, essentially, a product made or sold by the licensee that uses or is covered by some or all of the licensed IP rights. The term Licensed Product is important because it often (but not always) defines the licensee’s payment obligation. That is, the licensee often must pay the licensor a royalty based on the licensee’s revenue earned from sales of Licensed Products. So, every Licensed Product triggers a payment. For this reason, the definition of Licensed Product must specify that the product in question is covered by the licensed IP. The licensor is typically not legally entitled to collect royalties on a licensee’s sale of products that are not covered by the licensor’s IP, a practice that is referred to as “misuse” (see Chapter 24).

A basic example of a Licensed Product definition is set forth below. The Cyrix case discussed in Section 6.3 introduces additional complexities to this definition, particularly clause (a).

Licensed Product (Patent)

“Licensed Product” means a product that is (a) manufactured or sold by or for the Licensee or its Affiliates and (b) which is covered by any claim of the Licensed Patents.

Licensed Product (Patent + Know-How)

“Licensed Product” means a product that is (a) manufactured or sold by or for the Licensee or its Affiliates and (b) which is covered by any claim of the Licensed Patents or which embodies, or is manufactured using, any of the Licensed Know-How.

6.2.3 Territory

Every IP license has a territorial scope, whether implicitly through the inherent national character of intellectual property rights or, more typically, as defined in the agreement.

Some licenses are worldwide. That is, they allow the licensee to exercise the licensed rights everywhere in the world. Of course, no license is needed in countries and regions where the licensor does not possess IP protection for the licensed rights. A few countries lack patent laws entirely (e.g., Eritrea, Myanmar, Somalia), and it is only the most determined patentee that seeks and obtains patent protection in every country that does. In terms of copyright, 179 countries are parties to the international Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works, but Iran, Iraq, Cambodia, Ethiopia and a handful of others are not. Moreover, national IP laws are not recognized in international waters, or in space. Thus, while truly “worldwide” licenses may be overkill, there is little downside in granting worldwide rights when the licensor does not wish to impose any territorial restriction on the licensee’s activities.

Below the global level, parties may subdivide the world largely as they see fit. The territory of a license grant may be a city, state, country or larger region. Parties, however, often run into trouble when they try to define territories beyond national borders. Ill-defined regions such as “Asia Pacific”Footnote 16 the “Middle East” and the “US West Coast” (are Alaska and Hawaii included?) frequently appear in term sheets and letters of intent, but often lead to disagreements regarding the precise countries included within their scope. Even regions that may seem well-understood can harbor traps for the unwary. For example, when asked how many countries are in North America, many people will respond “three – Canada, the USA and Mexico.” But this is incorrect. There are around forty countries that make up the North American continent, including Caribbean nations such as Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, the Central American countries of Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Belize, as well as Bermuda, off the Atlantic coast of the United States, and the massive territory Greenland (currently held by Denmark).

The territory of “Europe” presents even more complexities. When speaking of Europe, one might mean the European Union (EU) (27 countries), the European Economic Area (the EU plus Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway), the Eurozone (19 of the EU countries), the European Patent Convention (16 countries), or the traditional “continent” of Europe, which includes Russia, Ukraine and other countries that are not a part of any of the major European trading coalitions. Moreover, even the EU is fluid, as the recent exit of the UK (via Brexit) demonstrates. License agreements that defined the licensee’s territory as spanning the European Union suddenly contracted on January 31, 2020, when the UK exited the EU.

Figure 6.5 The territory of “North America” consists of about forty different countries.

Perhaps the most precise manner of defining the territory of a license agreement is to list the specific countries included in the territory in a schedule or exhibit to the agreement, though this approach can have its hazards as well. Consider, for example, the patent and know-how licenses sponsored by the Medicines Patent Pool (MPP), an arm of the UN’s World Health Organization. The MPP obtains licenses from multinational pharmaceutical companies for the manufacture and distribution of lifesaving drugs in the developing world. A company granting such a license could specifically list the “developing” countries to which the license applied. But countries change status occasionally. India and China are, by some measures, still developing countries, yet many companies would hesitate to lump them together with far poorer countries for essentially philanthropic purposes. Instead of listing countries, a licensor could refer to an external list or index, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) list of “least developed countries,” a list that changes periodically.

A final note of caution with respect to territory definition is to ensure that the granting of licenses within defined territories is not a cover-up for the allocation of markets among competitors, a violation of the antitrust laws (see Section 25.3). Outside of the United States, competition laws and regional agreements may also limit the ability of parties to divide rights territorially. For example, the EU requires the free movement of goods, services, capital and persons among member states of the Union. Accordingly, agreements that prevent a party in one EU country from shipping goods to, or providing services in, another EU country may be invalid.

There is no foolproof method of correctly defining the territory of a license agreement, other than to draft carefully and thoughtfully with the intentions of the parties in mind and a good atlas at hand.

6.3 Grant Clause

With the nature of the licensed rights, and the markets in which the licensee may operate, established, the “grant” clause of a license agreement sets forth the precise legal rights that are granted to the licensee.

Grant Clause [Patent]

Licensor hereby grants [1] to Licensee a nonexclusive, [nonassignable] [2] license [3] under the Licensed Patent Rights, excluding the right to sublicense [4], to make, use, sell, offer for sale and import Licensed Products throughout the Territory.

Grant Clause [Copyright]

Licensor hereby grants [1] to Licensee a nonexclusive, [nonassignable] [2] license [3], excluding the right to sublicense [4], to reproduce, distribute, publicly perform and make derivative works of the Licensed Works throughout the Territory.

Grant Clause [Trademark]

Licensor hereby grants [1] to Licensee a nonexclusive, [nonassignable] [2] license [3], excluding the right to sublicense [4], to reproduce and display the Licensed Marks, without alteration, on Approved Products throughout the Territory and on advertising and promotional materials, tangible and electronic, promoting the Approved Products in the Territory.

Drafting Notes

[1] Present grant – although Stanford v. Roche (discussed in Section 2.3, Note 3) involved an assignment of rights rather than a license, its lessons about clear present grants of rights hold equally true in the realm of licensing. Avoid variants in the grant clause such as “shall grant,” “agrees to grant” and the like.

[2] Assignability – many license grants include the term “nonassignable.” Doing so could, however, conflict with the express assignment clause usually contained toward the back of the agreement (see Section 13.3). Rather than attempt to sort out any contradictory language when a merger or other corporate transaction is on the horizon, it is preferable to omit “nonassignable” in the grant clause.

[3] Right and license – the grant is of a “license.” Some agreements state that a “right and license” is granted, but this is unnecessary.

[4] Sublicensing – some licenses may be sublicensed (see Section 6.5), and if so, there will be a separate, often lengthy, section on sublicensing. However, if the intent is to prohibit sublicensing, it is efficient to do so in the grant clause.

Note that with respect to rights that are granted under statutory forms of IP (especially patents and copyrights), it is important to follow the statutory rights that are inherent in the licensed assets. Specifically:

The Patent Act establishes that the owner of a patent has the exclusive right to make, use, sell, offer for sale and import a patented article (35 U.S.C. § 271(a)).

The Copyright Act establishes that the owner of a copyright has the exclusive right to reproduce, prepare derivative works, distribute, perform and display various types of copyrighted works (17 U.S.C. § 106).

The Lanham Act establishes that the registrant of a federal trademark or service mark has the exclusive right to use in commerce, reproduce, copy, and imitate the mark (15 U.S.C. § 1114).

Keeping these distinctions in mind is critical when drafting the grant clause. Thus, if a patent is being licensed, it is nonsensical to grant a licensee the right to “display” the patented article or to “produce derivative works” of it, as these are not rights granted under the Patent Act. Likewise, granting the licensee under a copyright the right to “use” the copyrighted work can cause no end of confusion, as demonstrated by the decision in Kennedy v. NJDA, discussed in Section 9.1 (interpreting the word “use” in a copyright license to encompass the making of derivative works).

It is also important to note that these rights can often be granted separately, and not all rights need be granted to every licensee. For example, some patent licenses permit use of a patented apparatus, but do not grant the licensee the right to make or sell that apparatus. By the same token, some exclusive patent licenses may grant the licensee an exclusive right to sell a licensed product, but do not extend exclusivity to the use of that product. Copyright licenses can be limited to the right to reproduce a work, but not to create derivative works of it.

For IP assets that are not statutorily defined, such as know-how, unregistered trademarks, rights of publicity, database rights and the like, the drafter can be more creative regarding the authority granted to the licensee. Yet this additional flexibility can also lead to disputes, so the drafter must pay particular attention to defining the rights granted as precisely as possible to achieve the client’s objectives.

The Cyrix case excerpted below illustrates the importance of precisely defining the scope of the license granted.

77 F.3d 1381 (Fed. Cir. 1996)

LOURIE, CIRCUIT JUDGE

Intel Corporation appeals from the decision of the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas entering judgment in favor of Cyrix Corporation, SGS-Thomson Microelectronics, Inc. (ST), and International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), and holding that IBM and ST acted within the scope of their respective patent license agreements with Intel when IBM made, and ST had made, products for Cyrix. [We] affirm.

Background

Cyrix designed and sold microprocessors. Since it did not have its own facility for manufacturing the microprocessors it designed, it contracted with other companies to act as its foundries. Under such an arrangement, Cyrix provided the foundries with its microprocessor designs, and the foundries manufactured integrated circuit chips containing those microprocessors and sold them to Cyrix. Cyrix then sold the microprocessors in the marketplace under its own brand name.