1. Introduction

Brazil finds itself at a crossroads. Its status in international politics remains unclear, as its representatives and observers have variously positioned it as a middle power, an emerging economy, a member of the West, or a developing country (Carranza, Reference Carranza2017; Milani et al., Reference Milani, Pinheiro and Soares de Lima2017; Burges, Reference Burges2020; Esteves et al., Reference Esteves, Gabrielsen Jumbert and De Carvalho2020). Moreover, determining Brazil's position in global politics is complicated by the increased economic heterogeneity and political divergence of the developing country group over the past decade (Weinhardt and Schöfer, Reference Weinhardt and Schöfer2021). This in turn has major implications for Brazil's trade strategy and for its role in ongoing World Trade Organization (WTO) negotiations. On the one hand, WTO Members that self-declare as developing countries can access a catalogue of special legal rights. The exemptions and policy space entailed in this differential treatment – along with the practice of self-declaration – have recently become the focus of international contestation, thus placing the status of emerging economies under particular scrutiny in contemporary trade talks (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2022a). On the other hand, Brazil's status considerations also play a role in determining its negotiation strategy at the WTO, especially as it seeks to overcome entrenched divides that have regularly deadlocked negotiations.

This article examines how Brazil's status and negotiation strategy at the WTO has changed over the past decade. Its empirical foundations draw on WTO negotiation documents, government statements, dispute settlement case law, and a series of interviews conducted with Brazilian trade delegates in 2021 and early 2022.Footnote 1 This varied source material allows for an evaluation of two questions. First, who does Brazil primarily side with at the WTO – and have these coalitional patterns departed from an established status quo? Second, does such a shift also entail a change in negotiation strategy? To answer these questions, I develop a conceptual framework consisting of four emerging economy negotiation strategies reliant on different negotiation aims and different attitudes towards leadership of the developing country group.

I show that Brazil has fundamentally reconfigured its trade strategy away from a positive-sum developing country leadership strategy towards a flexible negotiation strategy. While in the early 2000s, Brazil's actions were based on leadership of a large and diverse group of developing countries, more recently it has developed a flexible approach that is far less reliant on developed–developing country divisions as structuring principles of its diplomacy. This becomes most evident in the disappearance of the Brazilian-led G20 from trade talks. Instead, Brazil has recently engaged in a set of joint proposals with the EU. It has further joined several plurilateral initiatives, including draft texts on new negotiation areas. These changes run parallel to a more heterogeneous list of dispute settlement targets when compared to the late 1990s and 2000s. Most notably, in the midst of ongoing contestation regarding the special rights of developing countries at the WTO, Brazil has signalled that it would begin to forego these rights in future and has remained absent from a Sino-Indian defence of the status quo.

These findings contribute to three strands of literature. In the debate about Brazil's status and role in international politics (De Carvalho, Reference De Carvalho, Esteves, Gabrielsen Jumbert and De Carvalho2020; De Sá Guimaraes, Reference De Sá Guimaraes2020), first it delineates how on trade issues Brazil has arrived at a very flexible self-conceptualization on the world stage. In pursuit of trade liberalization in agriculture, the breaking of negotiation deadlock consequently overshadows Brazilian status considerations at the WTO. Second, this implies that an established literature on Brazil's developing country leadership – and in general the leadership roles of emerging economies – requires more nuance (Doctor, Reference Doctor2015; Efstathopoulos, Reference Efstathopoulos2012). Third, the flexibilization of Brazilian trade strategy provides a counter-narrative to scholars that portray emerging economies – and Brazil in particular – as stuck in a ‘graduation dilemma’ (Margheritis, Reference Margheritis2017; Milani et al., Reference Milani, Pinheiro and Soares de Lima2017).

Below, an overview of Brazil's WTO leadership in the 2000s is followed by a literature review that outlines established debates on Brazil's negotiation strategy, its status, its developing country leadership role, and its ‘graduation dilemma’. I then introduce a theoretical framework for conceptualizing the different trade negotiation strategies available to emerging economies. Thereafter, the article analyses Brazil's recent activities and new directions at the WTO by examining coalition building, new negotiation issues, dispute settlement practices, and Brazil's engagement with developing country status. A conclusion ties together these findings to delineate a significant recalibration of Brazil's negotiation strategy over the past two decades. It finds that Brazil's strategy of gaining influence via leadership of the developing country group has been eschewed for a pragmatic and flexible approach that primarily seeks to bring movement into entrenched WTO negotiations.

2. Positioning Brazil in International Politics

Divisions between industrialized Members and developing countries characterized the WTO in the 2000s (Narlikar and Tussie, Reference Narlikar and Tussie2004; Narlikar and Wilkinson, Reference Narlikar and Wilkinson2004; Baldwin, Reference Baldwin2006). In order to underline recent recalibrations of Brazil's negotiation strategy, this section starts by unpacking the leadership role that Brazil attained in the first decade of the WTO era (1995–) as the head of an influential developing country coalition. This diplomatic status quo in turn forms the basis of an established academic literature that stresses Brazil's pursuit of prestige and followership as key mediating factors of its material interests in WTO negotiations (Doctor, Reference Doctor2015). Tracking the shifting position of Brazil in international trade negotiations thus holds relevance for three strands of literature. First, it speaks to recent scholarship on the role of Brazil in international politics and its attempts to straddle the divide between developing and industrialized economies. Second, this allows a re-evaluation of Brazil's leadership function at the WTO vis-à-vis the developing country group. Third, by delineating Brazil's status as a larger developing country and a coalition builder I re-examine the recent ‘graduation dilemma’ framework as an accurate explanatory tool for understanding allegedly contradictory behaviour in Brazilian foreign policy.

2.1 Brazil's 2000s Status Quo

At the outset of the twenty-first century, Brazil's trade priorities were closely aligned with the Australian-led Cairns Group, a mix of developed and developing countries that constituted strong agricultural exporters and primarily promoted trade liberalization (Taylor, Reference Taylor2000). Reliance on this smaller coalition was pushed aside in 2003 when Brazil fundamentally redrew its coalitional strategy and co-founded the G20 group of developing countries. Comprising Brazil, China, India, and a flurry of smaller developing states, the G20 strategically placed the Brazilian delegation – as its main representative – at the table with the most influential WTO players, including the United States (US), the European Communities (EC), Japan, and Australia (Efstathopoulos, Reference Efstathopoulos2012).

Several factors help to explain this shift. From an interests-based perspective, by the early 2000s Brazil – and other developing countries – continued to be disadvantaged by established negotiation practices, which centred on the European Communities and the US. In the 1990s, divisions between these two entities first had to be bridged via the 1992 Blair House Agreement before negotiations could be expanded to other traders for the completion of the 1995 Agreement on Agriculture (Preeg, Reference Preeg, Narlikar, Daunton and Stern2012, 129–131). This negotiation pattern persisted in the run-up to the 2003 Ministerial Conference in Cancún when a US–EC draft text on agriculture was tabled as a basis for negotiations. Overcoming this ex-post position in turn required a more central role for Brazil in international trade negotiations. As Brazil's then-foreign minister Celso Amorim put it:

The G20 has produced a change in the dynamics of agricultural negotiations, which migrated from the Blair House model to the NG-5 model [US, EC, Australia, India and Brazil] as far as decision-making is concerned. (Da Motta Veiga, Reference Da Motta Veiga, Stoler, Low and Gallagher2005, 117)

While Brazil also held export interests in developing country markets, its main priority at the WTO constituted the dismantling of heavy agricultural subsidy regimes, which in the early 2000s were primarily used in industrialized Members (Taylor, Reference Taylor, Lee and Wilkinson2007, 155–160). The particular framing of the WTO's post-2001 round of negotiations – based on the Doha Development Agenda – in turn imbued initiatives that claimed to integrate developing country interests with a greater legitimacy than previous negotiations (compare Maswood, Reference Maswood, Crump and Maswood2007). Against the backdrop of a failed Ministerial Conference in 1999 in Seattle – including protests by civil society actors – and the desire for political unity in the aftermath of the September 11th attacks (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson2006), the early 2000s thus provided an environment conducive to new coalition building focused around development. The impression that Brazilian interests were not adequately addressed in negotiations – and that the Doha Round boosted the legitimacy of these interests – was further supplemented by domestic political change. The advent of the Lula administration (2003–2010) entailed a change of foreign policy narratives, focussing on South–South cooperation as a bedrock of Brazil's role in international relations. Together, these imperatives allowed Brazil to abandon its established practice of participating in mixed coalitions and to assume leadership of a large and influential group of developing countries. Moreover, disappointment with the Cairns Group's reaction to the US–EC joint proposal on agriculture, submitted just before the Cancún Ministerial (WTO, 2003a), further fuelled the search for alternative bargaining groups amid the seeming paralysis of the Cairns Group (Da Motta Veiga, Reference Da Motta Veiga, Stoler, Low and Gallagher2005, 112).

The G20 thus emerged out of close coordination of the Brazilian and Indian WTO delegations and in response to a joint US–EC draft text on agriculture reform. Bringing together a large group of developing countries – including all three ‘BIC’ states – it primarily targeted trade distortions in industrialized economies while safeguarding existing special and differential treatment provisions for developing countries. This allowed the Brazilian trade delegation to pursue coalition building at the expense of its interests in developing country markets. As one trade delegate cited by Da Motta Veiga (Reference Da Motta Veiga, Stoler, Low and Gallagher2005, 112) noted:

Brazil had to reduce its ambition in market access issues in order to gather the support of India and China for its demands against developed countries’ domestic and export subsidies.

Moreover, G20 proposals referenced special product lists and a special safeguard mechanism for developing countries,Footnote 2 which sought to expand the policy space available to Members of the developing country group to protect their markets (WTO, 2003b). While these latter initiatives ran counter to Brazil's interests in liberalized agricultural trade, the G20's ability to block industrialized Members’ initiatives and increase Brazil's weight in trade negotiations helped to account for Brazilian lip service of new protectionist mechanisms for developing countries. Importantly, these safeguard issues were the core aims of the parallel G33 group of developing countries, which was led by India – and which Brazil did not belong to. The more protectionist thrust of the G33 consequently allowed the G20 to act as a complementary (yet not necessarily protectionist) entity targeting uneven liberalization. As one of the initial coordinators of the G20 stated:

We felt that very much of the legitimacy of the WTO rested on – if not reaching out to the whole of the developing world – then at least you have to have China and India on board. Although Brazil was not the largest trading partner, we were relevant in agriculture … . With that, and actually placing trust in our capacity to operate diplomatically, we would put Brazil in the spotlight … . I think what we had in mind was basically to sweep under the carpet our offensive interests in terms of the Indian and Chinese market … . So, what we did was dampen our ambitions in terms of our requests for taxing farmers in India and China, and then basically starting on domestic subsidies. (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 20 July 2021)

Brazil's heavy concentration on agricultural liberalization occurred in parallel to its more reserved approach to Non-Agricultural Market Access (NAMA) negotiations. Instead of pushing for greater market opening in manufactures and industrial goods, Brazil joined a group of developing countries – including India and Indonesia with South Africa as coordinator – to form the NAMA-11 in 2005. While on agriculture, developing country coalitions could vary in their goals and desire for protectionist flexibilities, both the NAMA-11 group and the Paragraph 6 Countries – which Brazil was not a member of – sought flexibilities or outright exemptions for market opening in industrial goods trade. In a NAMA-11 Ministerial Communiqué from June 2006, the group reaffirmed its guiding principle of ‘less than full reciprocity’ in liberalization commitments and its desire for agricultural talks to be pursued with the same level of ambition as NAMA negotiations (Ismail, Reference Ismail2009, 44–45). At the same time, developed Members sought ambitious NAMA concessions, providing a further line of strict developed–developing country division. This allowed Amorim to push back against high industrial tariff cuts proposed by the US and EC, calling for commensurate liberalization in agriculture. While he stated that Brazil would be willing to be more flexible on tariff formulas in NAMA, this was made conditional on a change in US and EU positions on agriculture (ibid., 48). Agricultural liberalization consequently remained the primary strategic goal for Brazil in WTO negotiations.

As Figures 1 and 2 outline, the value of Brazilian agricultural exports has consistently outstripped the value of imports in that sector. This gap has also widened dramatically in the past two decades, allowing the value of Brazil's agricultural exports to comprise more than 700% of its agricultural imports in 2021. In contrast, in manufactures Brazilian industrial interests are less clearly aligned with greater market access: the value of Brazil's imports and exports in this sector were roughly equal in the early 2000s. Moreover, from the middle of that decade onwards the value of Brazilian manufactures imports clearly and consistently outperformed Brazilian exports. A clear constellation of Brazilian agricultural interests in favour of exports and a more mixed industrial picture thus help to explain Brazil's preference for leadership on agricultural talks and its hesitancy to extend the same liberalization-oriented dynamism to NAMA negotiations (compare Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2015).

Figure 1. Brazilian Merchandise Trade in Agriculture

Source: Author's own calculations; WTO Database.

Figure 2. Brazilian Merchandise Trade in Manufactures

Source: Author's own calculations; WTO Database.

Following the 2003 breakdown of talks in Cancún, progress at the WTO was clearly dependent on the inclusion of emerging economies – and their developing country coalitions – at the highest levels of decision-making. An established pattern of US–EC coordination was interrupted, yielding in 2005 to the ‘New Quad’ consisting of the US, the EC, India, and Brazil. Different constellations of this group – supplemented by China, Australia, and Japan – persisted until the full collapse of talks in 2008, again over the issue of agriculture and special safeguard mechanisms (Efstathopoulos, Reference Efstathopoulos2012). Throughout this period, Brazil was included in high-level talks as a representative of the G20 while India could also claim to speak for the alternative G33 developing country group (ibid.). Unbridgeable divisions between the US and India over an agricultural Special Safeguard Mechanism in turn engendered the breakdown of talks, along with a continued impasse between developed and developing countries on the direction of NAMA negotiations (Wolfe, Reference Wolfe2015). Notably, during the 2008 mini-ministerial, Brazil agreed to a draft agricultural proposal sponsored by the then Director General, Pascal Lamy. This positional difference in this initial period of negotiations already implies incipient fissures between Brazil and other developing countries (compare Blustein, Reference Blustein2009). That said, the comments of Celso Amorim, Brazil's Foreign Minister at the time, reflect both a continued push for industrialized countries to make stronger commitments in negotiations and Brazilian opposition to agricultural draft texts that sought to include exceptions – including those to the benefit of industrialized Members:

Brazil has a key interest in the multilateral trading system and in its Development Round. President Lula has repeatedly said that Brazil will do its part, provided that others – and especially the rich countries – would do their own part … . As we can see from reading the agriculture text, we can take the conclusion that despite of all the good effort, that text was built on a logic of accommodating exceptions rather than seeking ambition. Almost 30 of the paragraphs in the agriculture text establish specific carve-outs for specific countries. (WTO, 2008a)

Brazil's push for greater liberalization in global agricultural trade contrasts heavily with its more protectionist imperatives on NAMA. In part, this can be explained by strong offensive interests in boosting competitive agriculture exports and by the influence of Brazilian agribusiness on Brazilian trade policy. Da Conceiçao-Heldt (Reference Da Conceiçao-Heldt2013, 442) delineates how organizations such as the Brazilian Association of Agribusiness and the National Industry Confederation (CNI) were active participants in the preparation of G20 positions together with the Brazilian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry and Foreign Trade. Indeed, Brazil's ability to coordinate and lead the G20 was supported by the information gathering of the ICONE think tank – itself sponsored by Brazilian agribusiness (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2013, 612). In contrast, Brazilian manufacturers were faced with significant import competition that did not yield a strong imperative for liberalization-oriented leadership at the WTO. The political influence of the trade union Labor Force pushed against further opening of the industrial market to international trade. This pressure was amplified by the Industry Federation of the State of São Paolo (FIESP) – the main representative of Brazilian manufacturing, which helped to solidify Brazil's protectionist position on NAMA in contrast to the National Agriculture Confederation's trade liberalism (Da Conceiçao-Heldt, Reference Da Conceiçao-Heldt2013, 437–440). Brazil's membership of the smaller NAMA-11 coalition in turn did not afford it the centrality in the early Doha Round that its leadership of the G20 did.

Brazilian trade strategy in the 2000s consequently rested on a new and unprecedented degree of influence on the outcome of WTO negotiations. This influence in turn hinged on Brazil's maintenance of a developing country leadership role and its coordination of a common developing country position at the WTO. The broader significance of Brazilian coalition building in WTO agriculture negotiations was underlined by a leading Brazilian trade analyst in the mid-2000s:

It is worth noting that the shift in Brazil's negotiations strategy was driven not only by the internal dynamics of the agricultural negotiations in the WTO, but also by a broader shift in the country's foreign economic policies – especially in its trade negotiations strategy – towards a view where the North–South axis acquired a growing relevance. Brazil's leadership in the setting of the G20 is perhaps the best example, at the multilateral level, of the country's new ‘southern’ stance in trade negotiations. (Da Motta Veiga, Reference Da Motta Veiga, Stoler, Low and Gallagher2005, 109–110)

Arguably, the inability of Brazil to bridge the varied positions in the G20 – in particular to fuse its offensive interests with the defensive positions of countries such as India – hindered this coalition from fostering solutions to issues in trade negotiations. Instead, the 2000s negotiations were characterized by an entrenched deadlock.

2.2 Negotiation Strategy and Status

The uncertain status of Brazil as either a member of the West, a powerhouse of agricultural exports, or one of the world's most populous developing countries has underscored discussions of its role on the international stage. As Soares de Lima and Hirst (Reference Soares de Lima and Hirst2006) note, the central aim of Brazilian foreign policy has consistently been to achieve international recognition of its supposedly ‘natural’ role in world politics. However, in doing so diplomatic narratives have historically had to incorporate different discursive elements to signal adherence to different groups. De Sá Guimaraes (Reference De Sá Guimaraes2020) underlines how the aspiration of belonging to the West is fused to a hesitancy to deny Brazil its credentials as a developing country. Finding a middle ground between these two positions has marked Brazil's diplomatic history, as it has attempted to play an intermediary role between global or regional superpowers on the one hand and a counter-hegemonic group of developing countries on the other. This most clearly comes to the fore in its claims of belonging to ‘another West’, stemming from its positioning in Cold War geopolitical divides (De Sá Guimaraes, Reference De Sá Guimaraes2020; Lafer, Reference Lafer2000).

In the twenty-first century, uncertainty over Brazil's hybrid status in international politics is reflected in the strategic narratives of the Lula administration (2003–2010). Against the backdrop of its increasing economic prowess – particularly in agribusiness – Brazilian foreign policy in the 2000s re-emphasized Brazil's connections to developing countries. For instance, Aoki Inoue and Costa Vaz (Reference Aoki Inoue and Costa Vaz2012) underline that in the field of official development assistance Brazil has become a ‘Southern donor’, a status that blends its developing country and industrialized economy credentials. Focussing on ‘South–South’ ties and avoiding hierarchical labels consequently form part of a Brazilian insistence on keeping its adherence to one of these two groups ill defined (ibid.). Moreover, it is of note that during the Bolsonaro administration (2019–2022), attacks on the institutions of the liberal international order – akin to the Trump administration's criticisms of multilateral governance frameworks – have not included overt targeting of the WTO (compare Casarões and Farias, Reference Casarões and Farias2021). Attempts to align Brazil with the US have however resulted in new approaches to Brazil's special developing country rights (see below). De Carvalho (Reference De Carvalho, Esteves, Gabrielsen Jumbert and De Carvalho2020, 20–21) describes the outcome of Brazil's ‘frustrated’ quest for status as follows:

Brazil's quest was complicated by the fact that while identifying with the great powers (of the Global North), Brazil, nevertheless, refused to relinquish its position as one of the leading states among the Global South. And while it was through the latter that Brazil came into a position from which it could legitimately aspire to great power status, being recognized as a great power would have meant that Brazil had to give up this condition of ‘hybridity’. By wishing to be a ‘great power from the South’, Brazil strengthened itself as the quintessential ‘hybrid power’, and therefore also condemned itself to hybridity and shattered dreams of great power status.

Brazil's status signalling in turn acts as a basis for its attempts to expand relations with developing countries whilst simultaneously promoting trade liberalization. Brazil's position as a ‘rising power’ thus does not go hand in hand with its emergence as a ‘challenger’ of an international status quo. Rather, as Kahler (Reference Kahler2013) notes, the economic success of emerging economies rests on their cautious integration into the international economy. This, in turn, means that the main catalyst for change in international politics comes from a negotiated reshaping of existing rules between rising and established powers (Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2013), not a radical overhaul of the system's core tenets. In climate politics, such a strategy of straddling the gap between industrialized Members and developing countries has allowed Brazil to move towards the core of decision-makers whilst accentuating an ideology of developing country solidarity (Hurrell and Sengupta, Reference Hurrell and Sengupta2012).

In trade, Brazil's formation and leadership of the G20 in the early 2000s engendered a similar increase in influence (see above). However, Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2016) argues that Brazil's use of the developed–developing country divide at the WTO is primarily strategic. Status ascriptions are thus mainly used to garner support for policies that promote the competitive position of the Brazilian agribusiness sector (ibid.). It is precisely the unclear nature of Brazil's position in world politics that forms the bedrock of its previous strength in 2000s trade talks. Elucidating how Brazil's position in trade negotiations has shifted since this point consequently promises to add a nuanced perspective on established Brazilian strategies that rely on the developed–developing country distinction – and a Brazilian bridging role – as key structuring principles of Brazil's diplomacy.

2.3 Leadership of Developing Countries

While recent developments in Brazilian trade strategy shed light on how Brazil navigates its intermediary status, this also has implications for its bargaining power. Rising powers have the ability to influence or co-manage international institutions via coalition building and cooperative leadership (Kahler, Reference Kahler2013). In the case of Brazil, the construction and leadership of such coalitions was the key theme of its trade diplomacy in the first decade of the twenty-first century. Burges (Reference Burges2013, Reference Burges2020) delineates how after the 1990s Brazil's foreign ministry attempted to compensate for hard power deficiencies by building alliances and promoting a discursive framework that places Brazil at the head of the developing country group. Particularly during the first Lula administration, this leadership strategy allowed Brazil to slow down disadvantageous policy initiatives stemming both from industrialized and developing Members, by signalling Brazil's supposedly unique position between the two entities (ibid.).

In trade, this diplomatic leadership takes two forms. On the one hand, Brazilian diplomats have stressed the promotion of a fairer and more economically balanced trading system along with greater inclusion of developing countries in key decision-making forums (Christensen, Reference Christensen2013). On the other hand, Brazil has been a spokesperson and (co-)founder of developing country coalitions in- and outside of the WTO. The G20 negotiation bloc on agricultural issues and the IBSA (India, Brazil, and South Africa) Dialogue Forum designed to facilitate coordination amongst emerging economies stand out in particular. In the eyes of Brazil's foreign minister, Amorim (in office from 2003 until 2010), such coalition building boosted prospects for engagement in global governance reform (Dauvergne and Farias, Reference Dauvergne and Farias2012). As Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2017) argues, Brazilian–Indian leadership of the G20 characterized a ‘tectonic shift’ that defied expectations on the (continued) marginal status of developing countries at the WTO. Instead, the quasi-veto power of this constellation catapulted both actors into the inner circle of trade negotiations.

However, coordination in this fashion, with the aim of establishing the broadest consensus possible, necessarily entails trade-offs. On the one hand, a new Brazilian influence at the top levels of trade policy-making rests on the legitimacy of its claim to speak for a wide and economically diverse set of developing country actors. On the other hand, Brazil's highly competitive, export-oriented agribusiness sector makes the opening up of developing country markets and the promotion of trade liberalization in industrialized Members desirable outcomes for its trade negotiators. These priorities in turn come into conflict with more diverse, defensive attitudes permeating the group it is claiming to represent. Narlikar (Reference Narlikar2010) suggests that precisely this uneasy task of keeping together a varied coalition whilst pursuing national trade interests engendered deadlock in the Doha Round.

Drawing on ideas concerning the power of cooperative leadership and the ability for developing country coalitions to boost Brazil's negotiation legitimacy and bargaining power, Efstathopoulos (Reference Efstathopoulos2012) goes even further, placing leadership at the heart of Brazilian and Indian trade strategy. Brazilian leadership thus supposedly consists of three dimensions: hesitance to engage in structural leadership; provision of leadership only when the preferences of followers overlap with Brazilian priorities; and, most significantly, the preservation of broad bases of followership as the key directive of external action (ibid.). This primacy of support by a large and varied group of other developing countries consequently conditions the actions of Brazil and India as leaders of developing countries. Maintenance of their central position in trade negotiations has hitherto necessitated strategies that centre on the blocking of industrialized state initiatives to avoid losing legitimacy amidst the pursuit of larger reform packages (ibid.).

The formation of large developing country coalitions at the WTO in the early 2000s has rightly been characterized by several academics as both a complete reorganization of international trade politics (Hurrell and Narlikar, Reference Hurrell and Narlikar2006) and as a significant power expansion for their leaders (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2015). Depictions of leadership and the maintenance of followership as the primary drivers of Brazilian trade strategy (Doctor, Reference Doctor2015), however, require updating. As Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2021) argues, while Brazilian diplomats have been quick to construct images of Brazil as a hero of the developing world – and this has (previously) resulted in greater prestige and bargaining power – the actions of Brazil and other emerging economies have often not helped developing countries more generally. Instead of leadership as an end in itself, the narrow pursuit of trade interests, disproportionately in agriculture, characterizes Brazilian trade strategy, with developing country leadership acting as a useful legitimacy tool (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021). This leads to a bifurcation of views. Some analysts place developing country leadership amongst the priorities of Brazilian foreign policy:

Although the vision of Brazil-as-developing-country and Brazil-as-champion-of-developing-nations has ebbed and flowed in importance over the years, it remains a key part of the current diplomatic lexicon. (Dauvergne and Farias, Reference Dauvergne and Farias2012, 908)

This contrasts with interests-based analyses that reserve a more marginal role for leadership in Brazilian international relations: ‘[A]lthough the identity of some actors may have changed, the same logic of power politics that has long characterized the WTO persists’ (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2021, 20). Beyond status considerations, this article consequently provides a clearer picture of Brazilian coalition building. Whilst previously, leadership of developing countries formed a central plank of Brazil's diplomacy, I argue that the 2010s witnessed a change of strategy that resulted in a more flexible approach.

2.4 Stuck in a Graduation Dilemma?

One conceptualization of recent changes in Brazilian foreign policy is provided by scholarship on the ‘graduation dilemma’. Margheritis (Reference Margheritis2017) posits that a lack of consensus about how larger developing countries ‘graduate’ in turn makes their actions in international politics seem less coherent. Instead of following a linear path to higher status, the rise of Brazil is accompanied by more complicated policy-making, thus producing a blurry picture of Brazilian foreign policy (ibid.). Unease with external expectations and status considerations thus brings Brazil into conflict with notions of responsibility in international relations (compare Bukovansky et al., Reference Bukovansky, Clark, Eckersley, Price, Reus-Smit and Wheeler2012; Kenke & Trote Martins, Reference Kenke and Trote Martins2016). Using human rights discussions and normative debates over the use of force, Harig and Kenkel (Reference Harig and Kenkel2017) delineate how Brazil's shift in the 2000s towards the centre of global governance went hand in hand with uncertainties over its role in shaping key international security norms.

The staggering and/or complicating effects of graduation are further stressed in research by Milani et al. (Reference Milani, Pinheiro and Soares de Lima2017), which underlines the different and contradictory expectations for Brazil from other actors in the international system. In particular, Brazil is caught between discursively emphasizing connections with developing states and accentuating its ability to bridge developed–developing country geopolitical divisions. This in turn holds implications for its prioritization of traditional alliances over new coalitions or vice versa (ibid.). The complicating influence of graduation expectations, both external and internal, further comes atop a long history of divides in Brazil's foreign policy elites that pit ‘Americanists’ against ‘Globalists’ and promote different development models and ideas about national autonomy (ibid.).

The confused picture that emerges of Brazilian foreign policy over the past decades is consequently portrayed as part of a larger phenomenon of rising powers ending up in a dilemma as they navigate their ‘graduation’. In essence, it is unclear what path or which policies will allow them to legitimately rise. At the WTO, such dilemmas can in turn hold particular salience, as graduation from developing country status is fused to the increasingly contested granting of special rights to emerging economies (Weinhardt, Reference Weinhardt2020). According to one Brazilian trade delegate cited by Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2017, 1395): ‘The issue that continues to unite us is graduation, so we're still close allies.’

However, while graduation holds the potential to complicate the picture of Brazilian international relations, I argue that Brazilian trade strategy is not fundamentally characterized by a graduation dilemma. Rather, Brazil has displayed a certain coherence in its attempts to break deadlock at the WTO. In pursuit of new multilateral rules – particularly on agriculture – this has engendered a more flexible attitude towards coalition building and an expanded purview of trade negotiations. While Brazil continues trying to act as a broker in international trade negotiations, the underlying direction of its initiatives do not betray the type of confused or disunited approach that would fit neatly into a ‘graduation dilemma’ framework. Recent developments in Brazilian trade politics further indicate that it has adopted a more flexible approach in the 2010s to its status as a developing country – or rather to its rights as a developing country – and has given up its strategy to achieve greater bargaining power via leadership of a broad coalition of developing countries.

2.5 Conceptualizing Trade Strategy Changes

The established literatures on Brazil's status in international politics, its leadership of developing countries and its ‘graduation dilemma’ raises important conceptual questions regarding the changing negotiation strategies of rising powers in multilateral trade politics. When do emerging economies opt to pursue leadership of developing countries? What types of leadership does this entail? Along which dimensions can we observe the positional change of large traders like Brazil? Combining insights from the above strands of literature, I develop a typology of trade strategies that relies on four ideal typical pathways for emerging economies (see Table 1).

Table 1. Trade strategies of emerging economies

I conceptualize change of positions as falling along two axes – changing negotiation interests and a changing emphasis on developing country status in a state's trade (or foreign policy) strategy. A state that pursues the advancement of further liberalization talks, yet clings on to a strong developing country framing performs positive-sum developing country leadership. This strategy entails negotiation positions that aim to achieve balanced liberalization commitments between developing and industrialized countries. As such, negotiations revolve around integrative bargaining and avoiding privileges and exceptions – particularly for industrialized countries – in trade texts. The pro-liberalization interests of such a state are consequently embedded in a conciliatory approach that seeks to promote mutual benefit and balanced commitments as a spokesperson for the developing country group.

Zero-sum developing country leadership in turn revolves around a state integrating its protectionist interests in the bargaining positions of the developing country group. Key tactics here involve the blocking of further liberalization initiatives, guaranteeing extant exemptions for developing countries – or negotiating new ones – and developing safeguards that can be used to offset potential liberalization commitments. In this case, distributive bargaining characterizes negotiations, as trade talks are bifurcated between liberalization-focused and development-oriented policies. At the WTO, where trade talks tend to move towards further liberalization – rather than more safeguards – such a negotiation strategy also pits zero-sum leaders, who do not hold an inherent interest in the progression of liberalization-directed trade talks, against their positive-sum counterparts who do. This divergence on the need for talks to advance also underpins the difference between a strategy of flexible negotiation and individualized protectionism. Both strategies stem from a merely peripheral use of developing country status in an emerging economy's trade (or foreign) policy.

A state that pursues a flexible negotiation strategy aims to overcome standstills in trade talks, even if this requires acting as a bridge between developing countries and industrialized countries or relying on an ad-hoc form of coalition building that rejects path-dependent groupings. A liberalization-oriented negotiation strategy again emphasizes the positive-sum, win-win nature of further trade talks; however, in this case, negotiation partnerships and fissures remain fluid.

Individualized protectionism, lastly, relies on halting further liberalization initiatives without recourse to leadership of a wider developing country coalition. In this case, an emerging economy may either adopt a blocking strategy that merely seeks to prevent further progress in trade talks or it may join ad-hoc groupings seeking to gain new safeguard mechanisms.

While these four strategies reflect ideal types, the three largest emerging economies – Brazil, China, and India – all occupy different positions within the above typology. The protectionist trade preferences of India, coupled with the deeply entrenched foreign policy framing of India as a geopolitical leader of developing states, encompass a zero-sum developing country leadership strategy. India's leadership of the G33 developing countries group and its focus on achieving new safeguards for developing states reflect this strategy (compare Narlikar, Reference Narlikar2020). China on the other hand – while also a member of the G33 – has exhibited a more selective use of its developing country identity and pursued protectionist interests in certain issue areas (Schöfer and Weinhardt, Reference Schöfer and Weinhardt2022). This behaviour tends more towards the individualized protectionism strategy. As outlined above, Brazil's trade negotiation strategy in the 2000s sought to both advance liberalization talks in agriculture and to catapult Brazil to the inner circles of trade negotiations via leadership of the G20 group of developing states. This reflects a positive-sum developing country leadership strategy. As I argue below, in the 2010s, Brazil shifted its trade strategy towards a flexible negotiation position, thus distancing itself from the developing-industrialized state binary that had previously allowed it to attain a central role in WTO negotiations. While a shift of this kind along the typology's horizontal axis involves giving up developing country bloc negotiation tactics in favour of more individualism (or vice versa), a vertical axis shift entails a move from integrative to distributive bargaining (or vice versa).Footnote 3

In terms of potential drivers of a state's shift within this typology, I consider four factors: economic interests, negotiation outlook, identity issues, and domestic political change. In essence, a state will shift its trade strategy if its underlying economic interests change, resulting in an altered attitude towards the desirability of further liberalization or more protections (compare Shirm, Reference Shirm2016). This could be the result either of domestic economic change rendering certain industries more or less competitive than previously or of changes on international markets, which alter the negotiation interests of an emerging economy. Similarly, a state's trade strategy might change if it perceives its current strategy to be counterproductive in on-going negotiations. If widening coalition membership or the changing economic profiles of individual coalition Members engender internal divisions or lessen the external legitimacy of coalition aims, this can hamper the prospects for achieving these goals. In particular, if countries interested in the progression of trade talks perceive their strategy as hindering consensus, they will opt for alternative strategies. In line with the literature on the graduation dilemma, a third potential driver is an identity shift on the part of emerging economies as their economic rise complicates their developing country status (compare Bishop and Zhang, Reference Bishop and Zhang2020 on China; Doctor, Reference Doctor2017 on Brazil). Finally, domestic political change, such as a change of administration could yield a re-orienting of an emerging economy's trade strategy reflecting different domestic constituencies and lobby group influences (compare Leeds and Mattes, Reference Leeds and Mattes2022).

Below, I examine Brazil's recent shift in trade strategy, delineating how the primacy of agricultural interests continues to underscore Brazilian trade strategy. That said, a desire to get liberalization-oriented talks moving has involved Brazil abandoning a strategy based on co-ordination of the developing country group. This reflects both Brazil's past experiences with such mobilization efforts – ending in negotiation deadlock – and the growing heterogeneity of WTO developing state Members. China and India's rise – for example as world-leading agricultural subsidizers – makes the bridging of divides less likely than previously when targets for Brazil's trade strategy could more easily be narrowed to distortions in industrialized Members. These changes in Brazil's economic interests and negotiation outlook, as well as – on certain issues – its domestic political changes, help to explain its trade strategy shift.

3. Brazil's New Directions

International relations scholars have previously stressed maintenance of followership and the leadership of powerful coalitions as core tenets of Brazilian foreign policy. This section delineates the myriad ways in which Brazil's strategic positioning at the WTO has departed from such a 2000s status quo. New coalitional patterns characterize Brazil's recent WTO activities, accompanied by a turn towards plurilateralism and new issues, as well as changes in its dispute settlement practices. Most notably, Brazil has adopted a highly flexible approach to its developing country status and the special rights that this status yields. Cumulatively, these new directions in Brazil's trade strategy comprise a pragmatic flexibility, detached from the developed–developing country distinction that had previously been central to Brazilian diplomacy.

These substantive changes to Brazilian economic diplomacy play out against the backdrop of the piecemeal restarting of WTO negotiations following their breakdown in 2008. In this regard, it is particularly noteworthy that Brazil attained a diplomatic victory when in 2013 the Brazilian Permanent Representative to the WTO, Roberto Azevêdo, became the new WTO Director General. One can partially attribute this to the developing country leadership role the Brazilian trade delegation held in the 2000s. Simon Evenett, for instance, argued that the strong free-trade orientation of the Mexican candidate Herminio Blanco garnered the support of most industrialized Members but could not do the same for developing countries (The Guardian, 2013). In contrast, Azevêdo's candidacy managed to see success with the backing of developing states, yet without significant support from industrialized countries (ibid.). However, Azevêdo's status as an insider and dealmaker of WTO politics with strong experience in the inner circles of negotiations certainly also played a role in determining his election. While some argue this centrality of a Brazilian diplomat in WTO politics ‘forced Brazil to become a more constructive player in negotiations’ (Financial Times, 2014), neither the positive-sum developing country leadership it displayed in the 2000s, nor its flexible negotiation strategy in the 2010s (described below) reveal an image of Brazil as a spoiler or blocker of talks. Rather, in the 2010s Brazil continued to pursue the same offensive interests in agricultural liberalization, albeit without recourse to developing country leadership. This stemmed from a negotiation outlook that desired to advance talks and avoid the type of deadlock that emerged in 2008, centred on divisions between developing country coalitions and industrialized Members. Identity issues in turn play no significant role in Brazil's strategy change. On the specific issue of special rights for developing countries, domestic political change with the advent of the Bolsonaro administration (2019–2022) arguably does play a role in Brazil's repositioning, however as shown below, new directions in Brazilian trade strategy pre-date 2019.

3.1 Coalition Building

While in the 2000s, Brazilian trade diplomats aligned themselves with other developing countries in order to target distortions in industrialized Members, by the latter half of the 2010s these coalitional patterns had fundamentally changed. This most clearly comes to the fore in a series of joint negotiation initiatives submitted to the WTO by Brazil and the EU.

The first and most successful of these texts resulted in the 2015 Nairobi decision on export competition (WTO, 2015a). Agriculture negotiations until this point had been structured along the three main ‘pillars’ of trade distortion, namely market access restrictions, domestic support regimes, and support given specifically to exports. In 2015, WTO Members effectively dismantled the third of these pillars by completely eliminating export subsidies. Moreover, while industrialized economies agreed to immediately dismantle their subsidy programs, implementation flexibilities for developing countries allowed them longer transition periods. Such consensus was in part achieved because by the time of the Nairobi Ministerial, only a handful of states were actively using export subsidies (South Centre, 2016). Indeed, for the EU, the regulation effectively rendered permanent the elimination of export subsidies it had achieved the previous year (ibid.).

Despite this limited scope for changes in practice, the decision marks a significant step forward in WTO negotiations for two reasons. Following the collapse of trade talks in the late 2000s, the adoption of substantive decisions on trade reform signalled the potential for paths out of negotiation deadlock. At the same time, the decision text drew on the last Doha agriculture draft modalities text (WTO, 2008b) and thus suggested that even on divisive agricultural issues, stalled negotiations could still provide results (South Centre, 2016). For Brazil, the move towards such co-authorship in turn stemmed from an impasse in the G20, the primary negotiation coalition that it had established and led a decade earlier. As a contemporary Brazilian delegate noted:

But then we couldn't achieve with this group [G20] the objectives we had in terms of promoting agriculture trade liberalization. So, in a way we kind of became a hostage of the group, in terms of positions… . So, at that time we were approached, we, Brazil, Australia and Canada were approached by the EU for an informal discussion on what we can do … . We basically started discussions on how we can tweak the Doha paper on Rev.4 on agriculture … and present it as a possible basis for discussion. So we did that. We revised the paper, which was almost agreed upon and we presented it as a joint paper for the Nairobi discussions to have a result on the export competition pillar. And we got it. (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 10 January 2022)

A shift in coalition strategy, away from a positive sum developing country leadership strategy is thus driven by two factors: The centrality of agricultural trade liberalization to Brazil's economic interests and a changing negotiation outlook. Dissatisfaction with negotiation standstill and the growing realization that the G20 did not allow the proper integration and promotion of Brazil's economic interests led the Brazilian trade delegation to reconsider which partnerships could be useful in advancing talks. As the above quote underlines, this was particularly done to avoid accidentally assuming a zero sum developing country leadership role, whereby Brazilian leadership of a more protectionist G20 would legitimize positions that did not match Brazil's interests.

This initial success took place outside the auspices of both the G20 developing country group and the Cairns Group. Moreover, it allowed for closer cooperation between Brazil and the EU in further initiatives. The most ambitious of these has been the 2017 Brazil–EU joint proposal on domestic support (WTO, 2017a). The regulation of subsidy regimes for agricultural products has proven to be one of the most divisive issues in international trade negotiations (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2019) and has traditionally pitted heavy subsidizers such as the EU against more competitive exporters like Brazil. The joint proposal, however, tackles the issue head-on by introducing overall caps to domestic support. Moreover, the draft negotiation text tabled two alternative forms of cap: one that allowed developing countries to continue subsidizing their agricultural sectors at a higher relative rate than developed ones (WTO, 2017a, para. 1A), and one that provided for longer timeframes for developing countries to reduce subsidies to a universal cap (WTO, 2017a, para. 1B). In both instances, the actual cap level and the target years were left open as a basis for negotiation, while least developed countries (LDCs) were exempt from reductions.

Although this negotiation initiative failed to translate into a Ministerial decision, it nevertheless marks an important caesura for two reasons. First, the tabling of a draft text on domestic support indicated a level of proactive negotiation on agriculture that contrasts with the more piecemeal revival of talks in the early 2010s. More importantly however, the Brazil–EU proposal contrasted heavily with a parallel proposal submitted to the WTO by China and India (WTO, 2017b). The inclusion of floating caps and special and differential treatment in the Brazil–EU text had initially been designed as a palliative to gain support from these larger traders and other developing countries (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 10 January 2022). Not only did this fail to engender the desired consensus, but the Sino-Indian text proposed to eliminate subsidization flexibilities for a handful of (mainly developed) countries as a prerequisite for any further negotiations on domestic support (WTO, 2018a, para. 2). This effectively pitted Brazil's proposal against that of the other two ‘BIC’ countries, marking a caesura in its trade strategy. As one Brazilian trade delegate stated:

I think this was the first time that Brazil acted alone as Brazil at the WTO and not through a coalition. It is easy to minimize this now, but I think that this was really an inflection point, a psychological inflection point for Brazil. You will find generations of Brazilian diplomats and strategists who think that Brazil should both geopolitically or multilaterally in international organisations act through coalitions. The developing world is perhaps one of the largest of these coalitions somehow … I think that the EU–Brazil proposal is an inflection point exactly because you see a sort of new generation of thought in Brazil's foreign policy coming and predicated on perhaps more realistic elements – in the sense that we recognize the weight of Brazil in terms of agriculture, in the global economy, and we act based on that. (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 30 August 2021)Footnote 4

While there had been Brazilian initiatives that devolved from a broad coalition building strategy previously, the co-submissions with the EU do mark a significant change as indicated above. This is because on the key issue of agriculture, where Brazil's core economic interests lie and where negotiations exclusively take place at the multilateral, WTO-based level, Brazil sought a more self-assertive role, detached from larger groupings such as the G20 or the Cairns Group.

From an interests-based perspective, Brazil's hesitancy to continue relying on North–South divisions in its trade strategy reflects a shift in its trade partners. While in the 2000s Brazil's major trading partners comprised the US and European traders – and its neighbour Argentina – by 2020, China had cemented its status as Brazil's top trade partner (see Figures 3 and 4). Moreover, as Hopewell (Reference Hopewell2019) shows, the 2010s also witnessed a tectonic shift in agricultural markets as emerging economies ramped up heavy subsidization regimes. Notably, this allowed China to become one of the largest and most trade distorting subsidizers worldwide, while it simultaneously became the global leader in terms of total agricultural value added (ibid.). By the 2010s, market distortions via subsidy regimes were no longer an issue primarily limited to the Global North. The growing salience of China's market and subsidization policy – as well as those of other emerging economies such as Indonesia – for Brazil's offensive interests in agriculture help to explain Brazil's search for new coalitional partners.

Figure 3. Brazil's Major Trading Partners 2000 (Developed Members emphasized)

Source: Author's own calculations, World Trade Integrated Solution

Figure 4. Brazil's Major Trading Partners 2020 (Developed Members emphasized)

Source: Author's own calculations, World Trade Integrated Solution

A re-orientation of Brazilian trade strategy – away from the G20 and large developing country coalitions – goes hand in hand with its attitude towards (and capacity for) leadership at the WTO. While in the early 2000s, the launching of the development-oriented Doha Round allowed for the increased influence of emerging economies in re-balancing industrialized state-dominated trade negotiations, by the 2010s this had changed. Instead, recent years have been marked both by on-going deadlock on key issues and by the overshadowing of negotiations by larger US–Chinese geopolitical competition. In the words of a Brazilian diplomat:

It would be almost impossible to have China, India, US, EC and Brazil, day one agreeing on a mandate on anything. It's not going to happen. Because we don't have this sort of air du temps, sufficiently powerful to amalgamate everyone together. There is no Washington Consensus, so there is no strong pressure to put those five together. So, if we insist that oh, it's only multilateral, the fact is, it's nothing at all … . It's a strong commitment to a multilateral outcome but at the same time making some … taking some flexible position in the understanding that there is not some sort of air du temps which would naturally make everything move forward. And at the same time, we are waiting a little bit for China and the US to find a solution (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 10 January 2022).

The implications that this lacking normative context and fragmentation of emerging economy positions hold for Brazil's erstwhile role – as coordinator and leader of the developing country group – are clear:

It's very easy to lead when you have everything in favour. When you have a nice mandate, China and India are not that big, agriculture is in the center, Washington Consensus is around. So that's an easy leadership. It's not that difficult to lead and to make this happen. But if you cut 2001, 2003, 2005, you put 20 years, 15 years ahead and come now: There is not at all ground to lead. Lead on what grounds? How am I going to come to China and lead China, lead India, lead South Africa? Each one of them wants to go in another direction. So there is no common ground to lead. (Brazilian trade delegate interview, 10 January 2022)

Here consequently, a changing negotiation outlook on the part of Brazil helps to account for its changing trade negotiation strategy. While a strong interest in the liberalization of agricultural trade continues to underscore the negotiation interests of Brazil, waning confidence in the ability to bridge or ‘amalgamate’ increasingly divergent positions has led it to reconsider the bloc leadership role that had previously allowed it to take an active part in negotiations with the largest players in trade negotiations. With the election of Azevêdo to the post of Director General there was further a move away from Pascal Lamy's previous reliance on coordinating such small groups of negotiation leaders, thereby weakening the incentive to continue acting as leader of the developing country group.

More recently, Brazil and the EU have continued their attempts to articulate joint proposals as potential platforms for breaking the deadlock at the WTO. According to some commentators, in the run-up to the 12th Ministerial Conference moves by Brazil and the EU to create a working group on WTO reform were strongly opposed by other Members – most notably India (Third World Network, 2021). Brazilian engagement with WTO reform further comes to the fore in its founding membership of the Ottawa Group – a Canadian-led coalition inaugurated in 2019 and dominated by developed Members such as the EU and Japan. Following MC12, this group published a Ministerial Statement reaffirming its desire to strengthen and render effective the WTO's negotiation function, as well as the need to solve the crisis of the WTO's dispute settlement arm (Government of Canada, 2022). New coalition building patterns aimed at overcoming the deadlock thus characterize Brazil's recent trade strategy.

3.2 New Negotiations Areas

Brazil's move towards a more flexible coalition building approach is mirrored by its engagement with new negotiation initiatives at the WTO. While in the 2000s, developing countries opposed the so-called ‘Singapore Issues’ – trade facilitation, competition policy, investment regulation, and government procurement (Evenett, Reference Evenett2007) – in the 2010s, Brazil took part in, or co-authored, several negotiation projects that constituted an expansion of the WTO's purview. The most notable shift was Brazil's decision to join the Revised Agreement on Government Procurement (GPA). The 2012 revision, which expands the scope of procurement regulated under its 1996 predecessor, is notable for two reasons. Firstly, it is a plurilateral agreement and thus has a much smaller set of parties than most WTO decisions. Secondly, this group of supporters consists primarily of industrialized economies. Historically, the liberalization of procurement contracts has primarily been of interest to developed countries, and so divisions over this issue have generally fallen along developed–developing state lines (Evenett, Reference Evenett2007).

Nevertheless, some developing countries have attained GPA observer status over the past two decades. Brazil became an observer in October 2017, ostensibly to aid the modernization of its economy and to better implement procurement provisions contained in regional trade agreements (WTO, 2017c). This was followed in May 2020 by Brazil's official application for accession to the GPA (WTO, 2020a), the first Latin American country to do so (WTO, 2020b). Already during the preparatory stages of the accession process, observers noted that Brazil's accession would greatly diversify the list of parties (WTO, 2020c). Brazil has in turn justified its accession by repeatedly stressing its desire to integrate more deeply into the world economy (WTO, 2020c, 2021a). In explaining this shift, one should also consider domestic political change in Brazil, with the Bolsonaro administration (2019–2022) explicitly seeking to reposition Brazil in international politics – for instance via OECD membership – away from previous Workers’ Party foreign policy framing reliant on developing country solidarity. Indeed, in a joint press release by the Ministry of External Relations and the Ministry of Economy concerning Brazil's revised offer for GPA accession, the Brazilian government stressed that adhesion to the GPA would bring the country in line with OECD recommendations (Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 2021).

A shift towards the plurilateral level is also evident in Brazil's recent support for joint initiatives concerning ‘non-traditional’ negotiation areas. At the December 2017 Buenos Aires Ministerial, Brazil was one of the initial co-sponsors of the Joint Ministerial Statement on Investment Facilitation for Development (WTO, 2017d), which sought to start structured discussions on a multilateral investment facilitation agreement. A revised statement followed in 2019 and re-emphasized the need to properly integrate developing countries into international investment flows (WTO, 2019a). Brazil's attempts to bridge divides and produce potential deadlock solutions are further underlined in its own investment facilitation proposals. In January 2018, Brazil submitted a Communication to the WTO General Council illustrating a potential structure for the negotiations envisaged in Buenos Aires (WTO, 2018b). Notably, the Brazilian delegation sought to stress its integrative role in the discussions:

This submission is not meant to be a negotiating proposal, but rather (i) a platform (among others) to promote more focused and text-based discussions, as well as (ii) a response to the call made in the Joint Ministerial Statement with regard to the ‘importance of continuous outreach to WTO Members, especially developing and least developed Members’. (WTO, 2018b)

The pursuit of plurilateral negotiations on investment facilitation was in turn re-emphasized in July 2020, when Brazil submitted a new, complementary proposal (Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 2020). The Brazilian delegation further co-sponsored a joint initiative on e-commerce, another new negotiation area (WTO, 2019b). Indeed, on this issue, Brazil has remained active and submitted its own draft text (WTO, 2019i), in parallel to submissions by Canada, the EU, New Zealand, and Singapore. Moreover, Brazil is part of the Informal Working Group on Micro, Small, and Medium-Sized Enterprises (WTO, 2017e) and counted amongst the initial sponsors of the Joint Initiative on Services Domestic Regulation (WTO, 2017f, 2019j). In the Ottawa Group's MC 12 statement, coalition Members (including Brazil) further underlined the potential that ‘flexible and open negotiating approaches, such as plurilateral initiatives, can play in supporting the WTO’ (Government of Canada, 2022). The significance of this Brazilian move to the plurilateral level to promote new negotiation initiatives is borne out by its strong previous reliance on multilateral diplomacy. As one Brazilian trade delegate noted:

For us, because of agriculture, because of the kind of results that we need, I would say that Brazil is the most interested country in really advancing multilateral negotiations. So this is, I think, the big point of departure where we're coming from. WTO negotiations for us are always number one: It has always been the big goblet that we need to get; this is the big prize … . So this vantage point, I think this is in the DNA of every trade negotiator in Brazil. (Brazilian trade representative interview, 10 January 2022)

While Brazil pursued new negotiation constellations in agriculture in the 2010s, its approach to non-agricultural market access remained relatively unchanged. In contrast to the strong liberalization interests of Brazilian agribusiness, Brazil's imports in the manufacturing sector increasingly outpaced exports during this decade (see Figure 2 above). This left Brazilian trade negotiators reluctant to push for greater tariff harmonization on this issue. Instead, the emergence of China as Brazil's primary source of imports occurred in parallel to international allegations of Chinese currency manipulation – and unfair competition of Chinese exports as a result (Staiger and Sykes, Reference Staiger and Sykes2010). Between April 2011 and November 2012, Brazil submitted three proposals to the WTO Working Group on Trade, Debt, and Finance to tackle the trade distortive effects of exchange rate misalignments (Thorstensten et al., Reference Thorstensten, Ramos and Muller2013, 373–374). In 2014, it further submitted a proposal for greater coordination between the WTO and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) on this issue (WTO, 2014a). At the same time, negotiations on NAMA did not significantly pick up pace again following the 2008 breakdown of talks. While Brazil continued to feature nominally in the NAMA-11 coalition of developing countries seeking flexibilities, the lack of movement in this negotiation area allowed it to focus on new issues and its pro-liberalization interests in agriculture.

At the 12th WTO Ministerial Conference held in June 2022, Brazil exhibited its continued emphasis on agriculture in multilateral talks, its desire to avoid protectionist imperatives in this field, and an imperative to keep trade negotiations moving. In particular, Brazil articulated a cautious approach to the issue of public food-stockholding, which encompasses government procurement of foodstuffs as a remedy for food security concerns. In a statement at the outset of MC12, Brazil reiterated its continued pursuit of reforms through agriculture negotiations and cautioned against blanket approval for stockholding programmes:

Market price support is the most distortive agricultural policy. Due to the well-documented negative effects on the international agricultural system, the curbing of market price support policies was one of the most important achievements of the Agreement on Agriculture. When procurements to build stocks are made through market price support, they cannot be left unchecked. (WTO, 2022a)

Brazil's zeroing-in on agriculture and on the protectionist potential of certain public food-stockholding measures reveals the continued centrality that economic interests in agricultural liberalization play for Brazil's behaviour in trade negotiations. Moreover, in a broader submission during MC12, Brazil proposed to alter the Ministerial Conference format by introducing yearly (as opposed to biennial) ministerial meetings. Such a move, according to the proposal would result in the ‘shielding of the multilateral trading system from a backlash of protectionism’, while ‘rebuild[ing] much needed trust among WTO Members’ (WTO, 2022b). Here again, Brazil's negotiation interest in the advancement of liberalization-oriented talks comes to the fore.

At the same time, Brazil did not feature prominently in MC12's heated debates on fisheries subsidies and a TRIPS waiver for vaccine production in developing countries. On fisheries, controversy primarily revolved around strong developing country carve-outs promoted and vehemently defended during the negotiations by India. While Brazil was not a vocal protagonist of these talks, its positions in the WTO Negotiating Group on Fisheries Subsidies in the run-up to MC12 clearly depart from such protectionist sentiments. Notably, in 2020 Brazil submitted its own revised proposal to reduce and limit Members’ fisheries subsidies (IISD, 2020). The TRIPS waiver issue on the other hand was carried mainly by South Africa and India, with controversy centring on the ability of China to make use of the waiver for its well-developed pharmaceuticals sector. Brazil remained absent from the list of supporters.

3.3 Dispute Settlement

Changes in Brazil's coalition building and its shift to greater acceptance of plurilateral initiatives were further complimented by changes in its practices of dispute settlement. In the 2000s, one of the factors that helped to establish Brazil as a leader of developing countries – and paved the way for the creation of the G20 – was its success in taking on developed countries in international arbitration. The year 2002 thus witnessed the launching of two Brazilian cases against the EU and the US. While the former tackled trade distortions caused by heavy European subsidization of sugar exports (WTO, 2002a), the latter sought to reduce US support for its domestic cotton producers (WTO, 2002b). Brazil won both cases in 2005, thus marking the first time that a developing country had been successful in agricultural dispute settlement against an industrialized actor. This in turn allowed Brazil to ‘construct a David-and-Goliath-like image of itself, as a hero of the developing world taking on the traditional powers’ (Hopewell, Reference Hopewell2013, Reference Hopewell2021, 8).

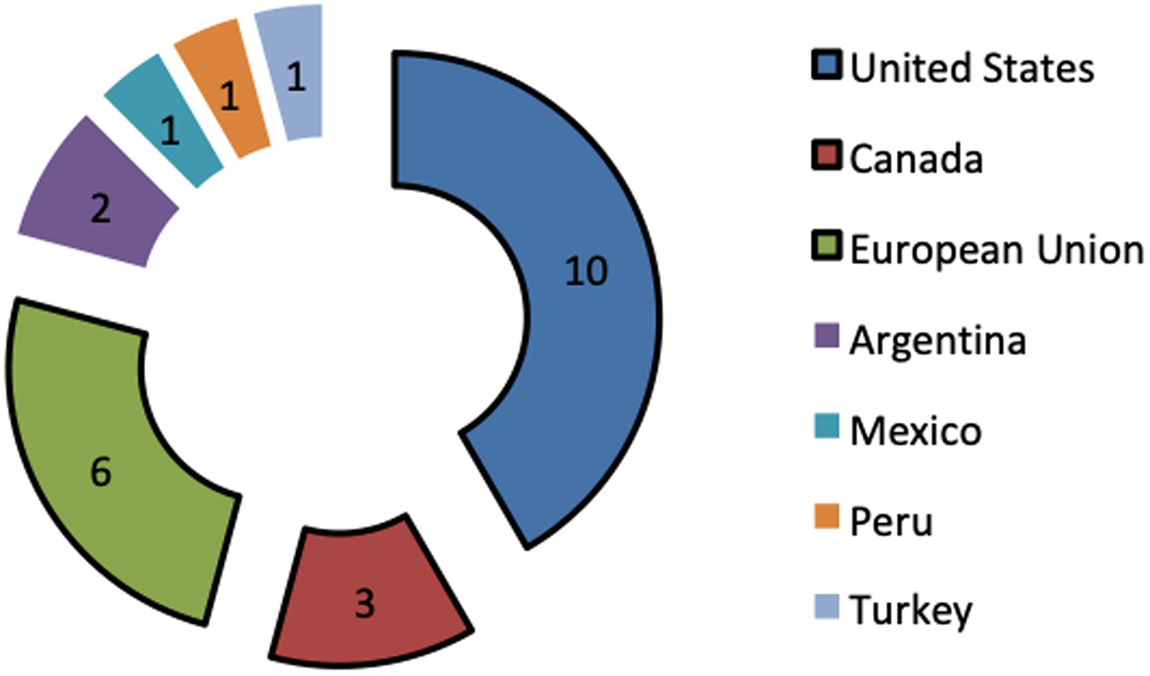

The legitimacy of Brazil's developing country leadership was – in the early 2000s – consequently derived from unprecedentedly successful legal targeting of subsidization practices in industrialized Members. Indeed, in the late 1990s and 2000s, Brazilian dispute settlement overwhelmingly focused on distortions in developed countries (see Figure 5 below). Over the past decade, however, this pattern has changed, with Brazil launching disputes against several developing countries. These include, for the first time, cases against China (WTO, 2018c), India (WTO, 2019c), South Africa (WTO, 2012a), and Indonesia (WTO, 2014b, 2016). While in the first half of the 2010s, Brazil targeted the poultry sectors of South Africa and Indonesia (compare WTO, 2012b, 2014c, 2015b), in the late 2010s, the Brazilian delegation launched complaints against Chinese and Indian sugar subsidies (compare WTO, 2018d, 2019d). Moreover, the latter of these initiatives was co-led with Australia (WTO, 2019c), the leader of the Cairns Group. While Brazil also continued to submit cases against the EU, the US, and Canada, the more heterogeneous makeup of Brazil's dispute settlement targets in the 2010s is of particular note. This is summarized in Figures 5 and 6.

Figure 5. Targets of Dispute Settlement Cases Launched by Brazil 1995–2009 (Developed Members Emphasized).

Figure 6. Targets of Dispute Settlement Cases Launched by Brazil 2010–2022 (Developed Members Emphasized).

Compared to other emerging economies, Brazil's newly expanded list of dispute settlement targets stands out. Cases involving China as a complainant solely focus on the US, the EU, and Australia. Disputes launched by India also overwhelmingly target the US and the EU, with the three exceptions (against South Africa and Argentina on pharma and Brazil on jute bags) all stemming from the turn of the millennium (WTO, 1999, 2001a, 2001b). Indonesia's single 2010s case against a developing country (against Pakistan on paper) is outweighed by its cases against the EU, US, and Australia (WTO, 2013). Brazil's 6–5 developing-industrialized state split does not match these cases and therefore does not fit into a potential larger pattern of increased litigation amongst developing countries. That said, the increasing participation of emerging economies, such as Brazil, in dispute settlement does reflect a growing legal capacity in many larger developing countries. As Shaffer (Reference Shaffer2021) shows, Brazil was the first of the BIC states to develop an in-depth knowledge of international economic law and whose domestic institutions – law firms, trade associations, civil society networks, consultancies, and government agencies – adapted accordingly. Indeed, the early build-up of legal capacity can explain Brazil's relatively strong (and early) use of WTO dispute settlement, although it is of note that this deeper history of legal capacity does not account for the shift to targeting a more heterogeneous group of Members compared to other emerging economies.

Clearly, Brazil's one-time focus on trade distortions in industrialized states has made way for a more flexible approach that targets heavy subsidization regimes both in industrialized and developing states. Whilst part of Brazil's positioning at the helm of the G20 had entailed the prioritization of offensive interests in industrialized economies – and thus the sidelining of interests in developing markets – recent years have seen a universal legal targeting of subsidies. This dispute settlement strategy is in turn less reliant on developed–developing country divisions as a structuring principle of Brazilian trade strategy. Reviewing Brazil's recent cases against other developing countries, this strategy shift is best explained by Brazil's economic interests and changes in the global economy. In particular, the emergence of China and India as major agricultural subsidizers over the course of the 2010s explains a new Brazilian focus on distortions in these economies. While previously, smaller-scale distortions could be overlooked in favour of using large developing country coalitions to target distortions in industrialized Members, such large changes in the international agricultural market have led Brazil to become more flexible in its dispute settlement practices and to target similar distortive policies in developing countries.

3.4 Developing Country Status

The strongest indicator that Brazil has recently left behind its use of developed–developing Member divisions to gain bargaining power in WTO negotiations relates to its official status as a developing country. At the WTO, special and differential treatment (SDT) provisions are reserved for Members that self-declare as developing countries. In contrast, SDT reserved for Least-Developed Countries (LDCs) is more clearly delimited, with UN-authored economic criteria determining when states are LDCs and when they graduate out of this developing country sub-group. The subsequent ability of emerging economies to avail themselves of certain exemptions, implementation flexibilities, and assistance mechanisms adds salience to Brazil's recent decision to forego such rights. On this contested issue, Brazil has come to an agreement with the US that it would begin to forego use of special trading rights granted to developing countries in future multilateral rules (Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 2019). The role of Brazil–US relations in this move is significant for two reasons: First, Brazil's voluntary rejection of developing country rights was explicitly leveraged against US support for Brazilian OECD membership (Agência Brasil, 2019). This re-positions Brazil more explicitly amongst industrialized economies. In the words of Brazil's then-Foreign Minister Araújo:

It's about admitting our condition as a great country, thus bringing ourselves center stage when it comes to decision making at the WTO. (Agência Brasil, 2019)