Introduction

The nature of the Czech electoral system is explicitly prescribed in the Constitution of the Czech Republic (hereinafter the ‘Constitution’). The Constitution grants legislative power to the Czech Parliament, which consists of two chambers: the Chamber of Deputies (hereinafter the ‘Chamber’); and the Senate.Footnote 1 To effectively secure the Senate’s role in the system of checks and balances (which presupposes the different political compositions of both chambers), different electoral periods (of four and six years respectively) and systems are prescribed for the chambers. While ‘elections to the Chamber of Deputies are held by secret ballot on the basis of universal, equal and direct suffrage, according to the principle of proportional representation’, the Senate is elected ‘according to the principle of a majoritarian system’.Footnote 2 The specifics of the electoral system, however, are left to be determined by the legislature and have been changed and also reviewed by the Constitutional Court of the Czech Republic Court (hereinafter the ‘Court’) several times in the past three decades.

Concerning the Chamber, the general approach of the Court to the electoral system review balances the constitutional requirement of proportional representation and the need to generate an effective government.Footnote 3 However, the latest decision of the CourtFootnote 4 regarding the electoral system to the Chamber seems to move distinctly towards favouring proportionality over effective government. The Court reviewed and quashed several provisions of the Parliamentary Election Act (hereinafter the ‘Act’)Footnote 5 as unconstitutional because the cumulative integrative effects of the provisions on the electoral system excessively distorted the proportionality principle required by the Constitution.

This case comment first provides a brief historical overview of the Act and the evolution of its constitutional review, both necessary for a proper understanding of the current ruling. The comment then presents a critical analysis of the Court’s decision and its reasoning, and explains why the decision can be considered at least partially surprising in the context of the legal argumentation hitherto provided by the Court. The comment finally considers the newly adopted electoral system with respect to the Court’s reasoning.

Journey to the current decision

The evolution of the Czech electoral system can be divided into four periods. After the reasonably proportionalFootnote 6 first period in the 1990s,Footnote 7 a significant change emerged in 2000 with an amendment to the Act, which aimed to strengthen the integrative mechanisms of the electoral system and consequently make stronger the positions of the two largest political parties at the time (social democrats and civic democrats). Formally, the system had to remain proportional, as the parties lacked the qualified majority in both chambers necessary to change the constitutional proportionality principle as such.Footnote 8 Yet the goal was to make it as disproportionate as possible. The electoral threshold remained at 5%, but the additive electoral thresholds for coalitions were raised to 10%, 15% and 20% of votes for coalitions of two, three and four or more parties, respectively.Footnote 9 Seats were then allocated using a modified D’Hondt divisors formula (starting at 1.42 instead of 1) in 35 fairly small constituencies.Footnote 10

This electoral system was found unconstitutional by the Court, ending this (relatively short) second period in 2001.Footnote 11 The cumulative effect of all the integrative mechanisms was found to violate the Constitution, as the electoral system had been changed to the point where it could no longer be considered purely proportional, as is required by the Constitution. Despite the opinions of several dissenting judges, one integrative mechanism was nevertheless upheld by the Court: the additive electoral threshold. The Court mentioned the possibility that it had been introduced by the two major parties for the purpose of significantly reducing the chances of the leading opposition coalition at the time – a coalition of four parties – entering the Chamber. However, regardless of whether the threshold was adopted in bad faith or not, it was not unconstitutional according to the majority of the Court.

The third period began with amendment of the Act in 2002 as a reaction to the aforementioned decision. By that time, the opposition had managed to gain a majority in the Senate, where a third of the seats were open for election every two years.Footnote 12 Because the Constitution required the consent of both chambers for electoral laws, a compromise was needed between the Chamber of Deputies, controlled by the parties which initiated the unsuccessful change in 2000, and the Senate, where the opposition had the majority. The once again reworked Act kept the electoral thresholds unchanged and stated that seats be allocated using the unmodified (slightly more proportional) D’Hondt formula in 14 (instead of 35) constituencies corresponding to self-governing regions. The electorate was distributed unequally, however, between the self-governing regions. As a result, the size of constituencies varied significantly (from 5 to 26 mandates).

Hence, this electoral system also suffered deficiencies in terms of proportionality.Footnote 13 While in large constituencies it led to fairly proportional results, in smaller ones the opposite was true. The low number of seats allocated using the D’Hondt formula was particularly harmful to smaller parties. In 2006, for example, the Green Party required over 56,000 votes to win a single mandate, while the two biggest parties needed just over 23,000 each. Put differently, with 6.3% of votes, the Green Party gained only six mandates in the 200-member Chamber, whereas, according to the proportional breakdown, it should have received 13.Footnote 14

As a consequence, the electoral system was challenged before the Court several times, but the Court refused to review the cases on merits, either for procedural reasons or because it found them manifestly unfounded.Footnote 15 Especially interesting was decision Pl. ÚS 57/06, in which the Court argued that elections can be legitimately organised on the territorial principle, even if this distorts the proportionality between the running parties at national level, because the Constitution does not specify exactly how the proportionality principle should be effected and leaves the choice of the relevant variant to the legislature.Footnote 16 Hence, the separation of the Czech Republic into 14 constituencies of unequal size, in combination with the D’Hondt formula applied exclusively in individual constituencies, was found to be in accordance with the Constitution. But this was not a plenary judgment deciding the case on its merits; it was only a procedural decision made by the senate consisting of three judges.

In the 2017 election, significantly disproportionate results again emerged. The largest party, ANO, received 29.64% of votes, which led to 78 seats (39%). At the other end of the spectrum, STAN received 6 seats (3%) for 5.18% of the votes. STAN therefore required roughly 2.25 times more votes to gain a seat than ANO did.Footnote 17 Once again, a constitutional review was initiated, which eventually led to the ruling that is the subject of this case note.

The first attempt was initiated by an individual voter, who unsuccessfully challenged the 2017 election results before the Supreme Administrative Court. Subsequently, he filed a constitutional complaint contesting the rejection decisionFootnote 18 and used the procedural opportunity to attach a motion for review of the relevant provisions of the Electoral Act.Footnote 19 The Court, however, did not find that there had been interference with the complainant’s individual fundamental rights and thus refused to review the complaint – and also the attached motion – on its merits.Footnote 20

The second, and this time successful, attempt was initiated by a group of senators who used their competence to commence an abstract review of the relevant provisions of the Act. After more than three years,Footnote 21 the Court issued its decision in February 2021. Contrary to all former rejections (and fairly surprisingly in this context), the Court found the concerned provisions unconstitutional and declared then void.Footnote 22 From now, therefore, we can speak about the fourth (as yet unknown) period of the Czech electoral system’s evolution.

The Court’s reasoning

Preliminary considerations of the Court

The Court identified three aspects of the constitutional review of the current electoral system as preliminary considerations.

First, the Court stressed the constitutional requirements of the equality of the running political parties and coalitionsFootnote 23 and the protection of the political minority.Footnote 24 Even though the Czech Charter of Fundamental Rights and Freedoms (hereinafter the ‘Charter’) explicitly grants the right to access any elective or other public office under equal conditions solely to citizens, the Court argues that ‘a right to proportional representation’ shall be derived from the Constitution and Charter.Footnote 25 One of the characteristics of the electoral system (proportionality) was therefore transformed into a (hitherto non-recognised) fundamental right granted to political parties and coalitions. The Court does not explain why such a step was necessary and how exactly it influences the approach of the Court to the proportional electoral system review. At least one important procedural implication, however, can be assumed: from now on, political parties have standing to file a constitutional complaint based on the claim that the disproportionate effect of the electoral system in a specific election infringes the aforementioned fundamental right.

The Court then articulated ‘the essential purpose’ of the proportional representation principle, which is to reflect social diversity in the Chamber’s political composition.Footnote 26 In contrast with the majority electoral system based on the principle of majority, says the Court, the proportional electoral system is based on the principle of protection of political minorities.Footnote 27 The essence of the proportional electoral system is therefore the right to proportional representation in the Chamber characterised as a national representative body, where each group of voters needs to be represented in a ratio which corresponds to the size of its proportion in the total number of voters.Footnote 28

Contrary to the above-mentioned previous decision,Footnote 29 the only relevant and legitimate criterion for distinguishing individual groups of voters is their political orientation (i.e., the running party or coalition which they support) at the national level. In other words, the legislature’s discretion in the electoral system design has been significantly restricted. Even though the legislature still can advance various objectives, including equal representation of territories, the objective sine qua non is to achieve proportional representation of political parties at the national level.

The second aspect highlighted by the Court is that when the legislature adopts the Act it decides in its own case and can potentially be in bad faith. The Act can therefore easily become an instrument for the cartelisation of current parliamentary parties, depriving others of free and equal political competition.Footnote 30 Combined with the previous aspect, the Court argued that changes in the electoral system which do not maximise its proportionality are considered to be made in bad faith.Footnote 31 The question of the consequences of the legislature’s bad faith for the (un)constitutionality of the concerned provisions was unfortunately not answered by the Court.

Finally, the third aspect mentioned by the Court vests in the constitutional requirements of equal suffrage and free choice of voters.Footnote 32 According to the Court, equality in general and the equality of suffrage are of a completely different quality under proportional representation than in a majority electoral system. Therefore, the Court needs to interpret this value in different ways with regard to the type of reviewed electoral system.Footnote 33 Unfortunately, the Court did not specify exactly how equality should be interpreted in a proportional electoral system. From the context of the reasoning and the case law of German Constitutional Court, which often serves as a source of inspiration for the Czech Constitutional Court, we can only assume that the Court wants to stress that equality in a proportional electoral system consists of not only equal voting rights (i.e. equal opportunity to influence the election) but also equal voting power (i.e. every vote cast should have the same weight in relation to the number of the gained mandates).Footnote 34 In other words, equality in a proportional electoral system requires proportionality.

In the following part of this section we would like to show why we find all three preliminary considerations of the Court rather problematic and questionable.

First of all, none of the preliminary considerations is explicitly explained, which leaves us only with assumptions concerning their impact on the review of the proportional electoral system.

Second, these considerations seem to modify the former approach based on balancing the proportionality principle and the ability of the Chamber to generate an effective majority in a way that strongly prioritises the principle of proportionality. As a result, the Court significantly restricts the space for the legislature to include integrative mechanisms into the proportional electoral system.Footnote 35 This would be perfectly legitimate if the Court’s reasoning did not suffer from several logical and theoretical misunderstandings, leading to a (mis)interpretation of the proportionality principle which makes it a supreme and almost inviolable value. With respect to the review of the electoral system of the Chamber, the proportionality between political parties at the national level seems now to be: (a) an inherent part of the principle of equality as far as the proportional electoral system is concerned; and (b) the only way to ensure that the Chamber accurately reflects social diversity.

Concerning the former point, the Czech Constitution, unlike the German Basic law, for example, explicitly requires both equality and proportionality in elections to the Chamber. Hence, we argue that there is no reason why equality of suffrage should be interpreted differently with respect to the character of the electoral system. The proportionality requirement is the essence of ‘proportional representation’ prescribed by the Constitution, not a derivation of equality. The Court, however, blends two independent principles (proportionality and equality) that are not interchangeable.

In our opinion, these two principles need to be distinguished in the following way. Equality of suffrage can be defined as each voter having equal opportunity (or probability) to influence the election results. But it does not guarantee each voter that the party they voted for will be (equally) successful, as the final results of the election depend on the distribution of voter support between the running parties, which cannot (or at least should not) be predicted in advance.Footnote 36 Consequently, even a significantly disproportionate electoral system does not necessarily violate the principle of equal suffrage. Let us imagine an electoral system with a 20% electoral threshold, which only two running parties were able to achieve and therefore gained all the mandates in a chamber for instance. Provided that the common flaws (such as the inequality of ratios between the constituency magnitude and the number of votes cast in the constituency which would indeed cause the inequality of votes between constituencies) are avoided, no reason exists to claim that even such significant disproportionality caused any inequality of suffrage, since every voter had the same opportunity to influence the elections and determine which of the running parties would or would not achieve the required electoral threshold.Footnote 37

In contrast, the principle of proportionality focuses exclusively on the characteristics of the electoral system and requires that each group of voters be represented in a ratio which corresponds to the size of its proportion in the total number of voters.Footnote 38 Although majority electoral systems can (rather coincidentally) generate sufficiently proportional results,Footnote 39 this demand can be (reliably) satisfied exclusively by the proportional electoral system. Hence, the reviewed electoral system for the Chamber could have been held unconstitutional for violating the requirements of proportionality but not because of the inequality of suffrage.

Regarding the latter point, we believe that it is not true that only the proportionality at the national level reflects social diversity and is able to provide every group of voters with their representation.Footnote 40 On the contrary, majority electoral systems can provide representation to even less significant groups of voters if they are concentrated in a few constituencies where they can reach sufficient support.Footnote 41 Given that social cleavages often depend on geographical parameters,Footnote 42 the Court’s assumption that the perfect reflection of social diversity will only be provided by proportional representation at the national level does not seem to be valid. It leads to an oversimplification of social diversity, transforming it into the one-dimensional competition between the few (or several) sufficiently significant groups of voters at the national level.

To conclude this analysis, none of the three preliminary considerations mentioned by the Court are explained in a solid and sufficiently persuasive manner. Moreover, none of them was actually necessary for the judgment itself, since the Court does not apply them in the following part of the judgment where it reviews (and quashes) the challenged provisions of the Electoral Act. A judgment missing these 20 pages of preliminary considerations would smell as sweet and lead to the same result.

Besides the three preliminary considerations, the Court once againFootnote 43 underlined the need to review together all the integrative mechanisms in the electoral system since their disproportioning effects accumulate.Footnote 44 Such an approach is in line with the current mainstream of electoral specialists, who acknowledge the significant influence which constituency magnitude hasFootnote 45 but also emphasise the importance of other variables, most importantly whether all seats are distributed at the constituency level or whether a second scrutiny exists at the national level.Footnote 46 This, however, does not necessarily imply the need to quash them all if their cumulative effect is found to be unconstitutional. On the contrary, the self-restraint doctrine suggests that the Court interfere as little as possible in the electoral system to fulfil the constitutional requirements of proportionality, equality, free political competition and protection of political minorities.Footnote 47

Fourteen constituencies and the D’Hondt formula

Moving to the individual challenged provisions of the Electoral Act, the Court quashed several of them but not all. The first major intervention was the quashing of the D’Hondt divisors allocation formula.Footnote 48

The Court argued that the level of disproportionality of the electoral system was unconstitutionally high due to the combination of: (a) the existence of 14 constituencies of unequal size (from 5 to 26 seats);Footnote 49 (b) the D’Hondt formula itself, which can lead to disproportionate results, especially in smaller constituencies;Footnote 50 and (c) the fact that seats are allocated separately within these constituencies without any compensatory possibilities (second scrutiny, compensatory seats, etc), which would foster proportionality at the national level.Footnote 51

The Court stressed that the D’Hondt formula, per se, is not unconstitutional;Footnote 52 the unconstitutionality emerges when it is combined with 14 constituencies of unequal and relatively small size.Footnote 53 One of these two features of the electoral system therefore had to be quashed, and the Court selected the D’Hondt formula. The Court attempted to explain this choice, (suddenly) arguing that the main problem does not lie in the mere existence of 14 constituencies but in the fact that all seats are allocated exclusively within them.Footnote 54 Quashing the 14 constituencies would therefore be the most intensiveFootnote 55 and yet unnecessary intervention into the current electoral system.Footnote 56 However, this choice is inconsistent with the aforementioned reasoning, which primarily targets the problematic nature of the 14 constituencies and consequently leaves significant uncertainty concerning the constitutionally acceptable degree of disproportionality of the electoral system in the future.Footnote 57

In addition, the Court quashed the Hare quota used with the largest remainder method for the allocation of seats between constituencies (i.e. the mechanism which guarantees that seats will be allocated proportionally between constituencies). Even this formula, per se, was found perfectly constitutional and was quashed only because, according to the Court, it was (again quite surprisingly) an essential component of the overall unconstitutional electoral system.Footnote 58

Additive electoral threshold

The second major intervention was the quashing of the additive electoral threshold for running coalitions. This decision is even more surprising since the threshold has already been reviewed on merits and has not been found unconstitutional.Footnote 59 This part of the petition should, therefore, have been rejected as inadmissible since it was related to a matter upon which the Court had already passed judgment.Footnote 60

The Court argued that the additive threshold was challenged for a different reason than in the former judgment. The new reason was found in the empirical data, which indicated the real impact of the threshold in preventing coalitions from being formed.Footnote 61 New data (or evidence), however, does not automatically mean new reasons.Footnote 62 On the contrary, precisely the same argument based on the discouraging effect of the threshold was mentioned (and rejected) in the former judgment.Footnote 63

Nevertheless, the Court changed its legal opinion and quashed the additive threshold for two relevant reasons. First, the threshold could cause an unconstitutional infringement to the proportionality principle because a potentially enormous proportion (up to 19.9%) of votes for a single running coalition would not be counted in the scrutiny and would not therefore result in any seat gained.Footnote 64

Second, it violates the equal opportunities of running coalitions since they need to reach a significantly higher proportion of votes to gain any seat despite the fact that they still have the same financial and other limits concerning the election campaign.Footnote 65

The Court emphasised, however, that this argument applies solely to the current additive electoral threshold of 10%, 15% and 20%, suggesting that the lower additive threshold could be acceptable.Footnote 66

The new electoral system and its consequences

Since the Court is given only the competence to quash but not create legal norms,Footnote 67 it refused to specify what the new electoral system should look like.Footnote 68 The legislature was therefore left with several options, as long as the constitutional requirements as interpreted by the Court (especially sufficient proportionality at the national level) were fulfilled.Footnote 69

Pressured by time because the Court’s decision was issued nine months before an election, the parliamentary parties had to arrive at a compromise. The new electoral systemFootnote 70 consists of two scrutinies. Electoral thresholds (5% for single parties, and from now on, 8% and 11% for coalitions of two and three or more parties, respectively) are still included. The reduction of the additive electoral threshold for coalitions should weaken (but not entirely eliminate) the reasons why the Court held the former additive threshold unconstitutional.

In the first scrutiny, seats are allocated within the same 14 constituencies using the Imperiali quota instead of D’Hondt divisors. The unassigned seats from all the constituencies (if any) as well as remaining votes for various political parties which were not used for allocation of any seat in the first scrutiny are then allocated at the national level using the Hagenbach–Bischoff quota with the largest remainder method. The function of the second scrutiny ought to be the compensation of possible disproportionalities caused by the fact that only 4 of the 14 constituencies are large enough (i.e. over 20 seats) to guarantee sufficiently proportionate results even for smaller parties. The compensatory system of the second scrutiny, however, can work only when an adequate number of seats remain unassigned in the first scrutiny. The Imperiali quota is not the ideal formula in this respect since – in contrast to the Hare or Hagenbach–Bischoff quotas, for example – it is constructed with quite the opposite goal, i.e. to distribute as many seats as possible. Hence, to gain one seat in the second scrutiny requires more votes for the running parties than to gain it in the first one, which amounts to a systemic bias harming the smaller parties who rely more on the second scrutiny.

Consequently, the new electoral system should generate more proportional results at national level and therefore be in greater accordance with the constitutional requirements as interpreted by the Court. Nevertheless, it does not guarantee the proportionality to be absolute because of the aforementioned effect of the Imperiali quota.

To support this argument, we compared the real results of the previous three elections in the Czech RepublicFootnote 71 with the results of: (a) a hypothetical proportionate breakdown, in which the proportion of votes for each party achieving the electoral threshold equals the proportion of seats gained;Footnote 72 and (b) a newly adopted electoral system (Figure 1).

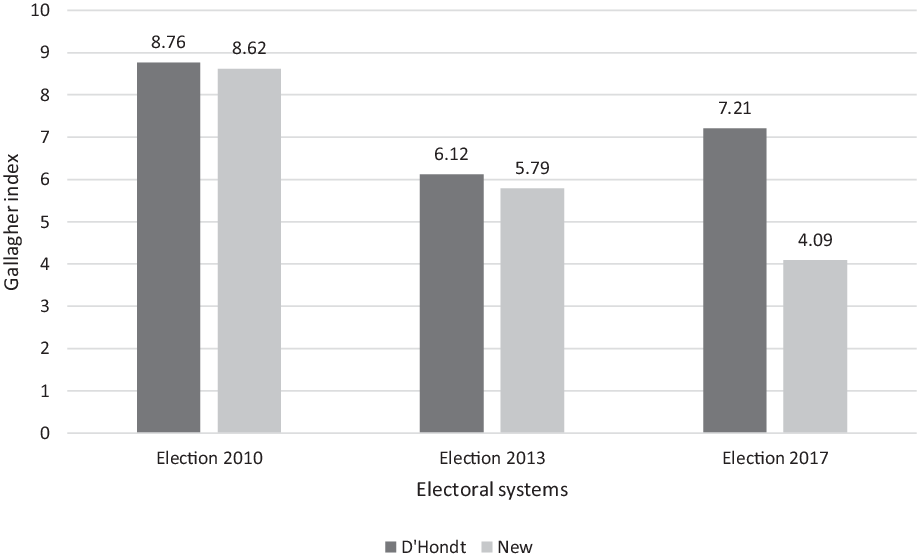

We also calculated the Gallagher index of disproportionalityFootnote 73 of both electoral systems for each of the three elections (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Comparison of the three electoral systems in the previous three elections

Figure 2. Gallagher index of disproportionality of both electoral systems for each of the previous three elections

Finally, to achieve a better level of sensitivity concerning the distribution of seats between parties which actually entered the Chamber, we calculated the average relative changeFootnote 74 between the hypothetical proportional breakdown and the results of both electoral systems for each of the three previous elections (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Average relative change between hypothetical proportional breakdown and the results of both electoral systems for each of the three previous elections

The results reveal that the newly adopted electoral system would indeed have generated less disproportionate results in all three of the previous elections. It should, therefore, be more in accordance with the Constitution. Nevertheless, for the reasons explained above, the new proportional system is still nowhere near perfectly proportional, otherwise its Gallagher index would equal zero, which it obviously does not. The seats are still distributed rather disproportionately between parties, even if we ignore the effect of electoral thresholds, since the average relative change between the proportional breakdown and the new electoral system remains significant. Applying the new electoral system to the above-mentioned example for the 2017 election, ANO would have needed on average 21,741 votes to obtain one mandate whereas STAN would have needed on average 29,129, which is still roughly 1.34 times as much. Given the rather strict yet vague preliminary considerations of the Court, we cannot be sure that even the new electoral system will not be held unconstitutionally disproportional in the future.

Conclusion

In the present case comment, we have argued that the former electoral system in the Czech Republic had deficiencies which caused it to be significantly (and perhaps even unconstitutionally) disproportional. In this context, the Court’s decision to quash some of the integrative mechanisms of the system is not only acceptable but also perhaps desirable.

Nevertheless, a problem remains in that the decision is not well explained, often inconsistent, contradictory, and generally based on deficient preliminary considerations, especially the unexplained ‘bad-faith’ of the legislature, the blurring of the requirements for proportionality and equality and the argument that the social diversity can only be reflected by the proportionality between political parties achieved at the national level.

Consequently, we know that the electoral system needs to be more proportional, but it is not clear how much. The newly adopted electoral system has indeed been found more proportional, but the Court’s preliminary considerations are so vague that it is by no means certain that the Court might not quash even this electoral system for the same reasons as the previous one.