Service increment for teaching funding

Exposure to real patients in a real clinical environment is a cornerstone of medical undergraduate education. Marrying the twin needs of delivering a clinical service for patients and delivering the educational needs for students provides challenges for both clinician time and clinical resources. Financial pressures within the National Health Service (NHS), reduction in the number of clinical academics and a concomitant increase in the number of medical students have made these challenges more acute. 1,2 In addition, there has been increased debate as to how to best involve patients in medical student teaching. Reference Tew, Gell and Foster3 In psychiatry, further pressure has been added on account of dispersed community care and the creation of specialist teams, leading to a reduction in the number of in-patients where traditionally most of the medical student education is delivered. The new contract for consultants with well-defined job plans with programmed activities has meant that in some cases medical student education, once an integral part of most consultants' work, has now been crowded out of an ever pressured job plan. Even if the time for medical student education is part of the contract, heavy clinical commitments may mean teaching is still not delivered.

Service increment for teaching (SIFT) is funding support for the NHS in England to specifically deliver undergraduate medical education as a recognition that clinical education is not resource-free. Similar funding mechanisms operate in the other UK home nations: additional costs of teaching in Scotland and supplement for teaching and research in Northern Ireland; in Wales, the Welsh Assembly funds both SIFT and the direct costs of university medical education. Concerns have been raised about the lack of transparency in the use of this funding and more specifically that NHS trusts have diverted this ‘education funding’ to plug deficits in clinical services. Reference Hitchen4

This paper provides a brief introduction to medical student education funding with a specific focus on SIFT allocation and suggested guidance on maintaining an audit trail of this funding flow illustrated with a case study of a new graduate entry medical school in Derby. Although the focus of this paper is on the practice in England, the issues raised may be applicable across the UK. Readers interested in the historical origins and development of SIFT funding are referred to excellent reviews by Bevan Reference Bevan5 and Clack et al. Reference Clack, Bevan and Eddleston6

Medical SIFT

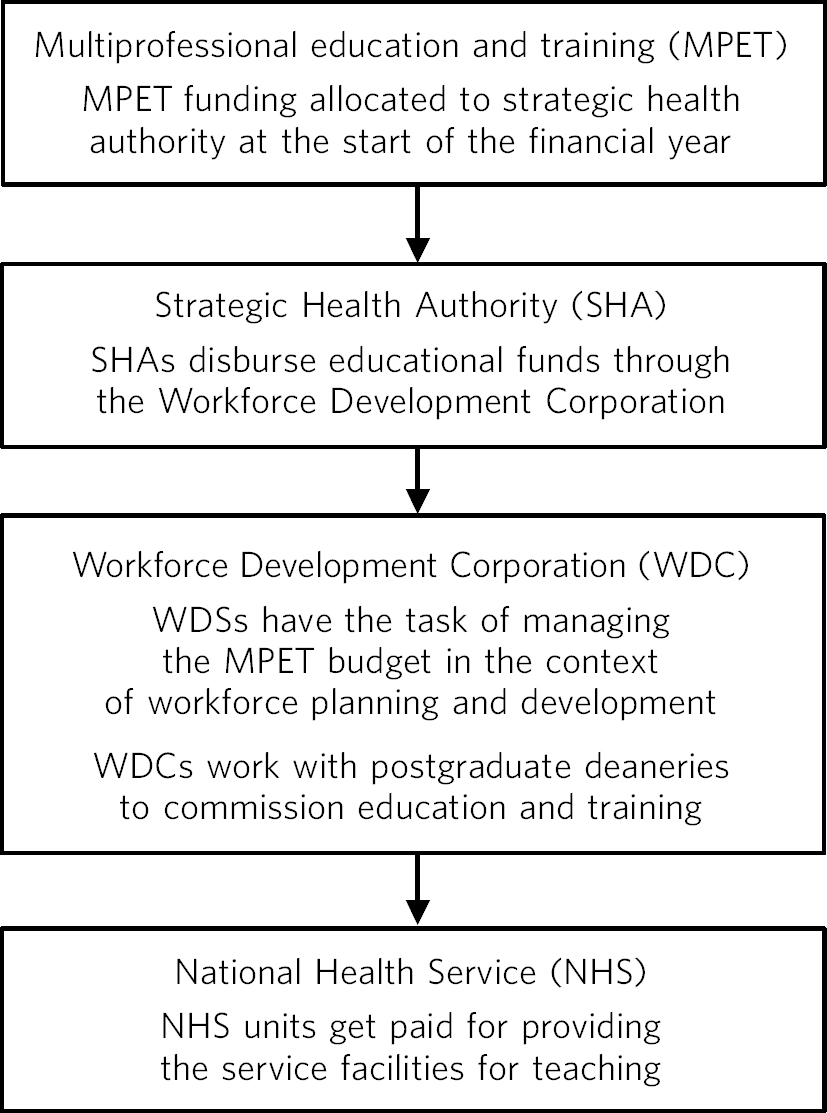

Figure 1 demonstrates the source of medical education funding in England and Fig. 2 indicates the disbursal pathway of these funds.

Fig 1 Medical student education funding in England. In Wales, the Welsh Assembly funds both SIFT and Higher Education Funding Council for Wales; additional cost of teaching (ACT) and supplement for mental and dental education (SUMDE) are the SIFT equivalents in Scotland and Northern Ireland respectively.

Fig 2 Multiprofessional education and training funding flow.

As mentioned above, SIFT is not a payment for actual teaching but is meant to cover additional costs incurred by NHS trusts in delivering medical student education. This additional funding ensures that provider trusts which provide undergraduate medical education do not lose out compared with those that do not have medical students. 7

Historically, the large university teaching hospitals gained a substantial sum through SIFT and this was typically calculated on a per capita basis (number of whole-time equivalent students in the last 3 years of their 5-year curriculum, Reference Clack8 the last 3 years traditionally being the clinical years).

The Winyard report 7 suggested a break from the sole reliance on per capita funding to a system based on both clinical placements (linked to student numbers) and costs for facilities to support training (independent of student numbers). The latter now forms the bulk of SIFT comprising nearly 80%, with the per capita element forming only 20% of the overall SIFT income for trusts. This model was meant to improve accountability, with funding linked to demonstrated costs rather than being a fixed sum linked to student numbers. 9 It was also hoped that this format of funding would promote positive changes in the delivery of medical education with financial incentives linked to performance.

Problems with SIFT

Calculating the costs of teaching

In theory, the new funding arrangements ought to promote accountability, but in practice trusts have found it difficult to link SIFT money to specific outcomes. This is partly due to the inherent difficulty in calculating the additional costs involved in teaching: for example, it is difficult to estimate the medical students' costs to the trust of a ward review where there are postgraduate trainees as well as nursing students. Reference Clack, Bevan and Eddleston6 Similarly, it is difficult to calculate the costs of an out-patient clinic running slower due to medical students, along with the costs of the facilities (e.g. additional chairs for medical students, larger rooms).

Supervising SIFT spending

Apart from these difficulties, NHS trusts have traditionally been lax in tracking SIFT money, with funds disappearing into general trust funds. As per Department of Health's own accountability reports, it is not known how recipient trusts use SIFT money. 10 More worryingly, there is anecdotal evidence that SIFT money has been used to fund overspend deficits in NHS spending 11 or in central contingency funds. Reference Hitchen4 Quite often it seems that the difficulty in differentiating between NHS clinical costs and NHS teaching costs has been allowed to excuse the merger of SIFT money in the NHS trusts' baseline income pot. Reference Gutenstein12

It does not help that most trusts (especially mental health trusts) do not have a separate education business unit and so SIFT money tends to end up in one business directorate or another without any direct links to actual teaching-related expense. This prevents ring-fencing of SIFT funds for medical education. This problem is well-demonstrated in the British Medical Association's Medical Academic Staff Committee Survey, 13 which found that about half of the NHS trusts were unable to account for how their SIFT funding had been used. Only a third of the trusts were able to demonstrate a link between SIFT allocation and academic sessions by consultants (as reflected in their job plans). Many trusts seem to allocate one ‘nominal’ programmed activity for teaching with little relationship to actual teaching activity. 13

Uneven distribution of funds

At a conceptual level, the purported link between funding of education and rational development of workforce seems tenuous, especially considering the old SIFT formula whereby an acute teaching hospital would get the lion's share of SIFT money (90% of all SIFT allocation in 1996–97 went to teaching hospitals) with only 10% for other sites where teaching would take place (including primary care, community clinics and psychiatric hospitals). Reference Bevan5

Vertical integration of the curriculum

Another problem is that old SIFT calculated the per capita costs based on teaching in clinical years. With vertical integration of the curriculum and the problem-based learning curriculum in some schools (e.g. Derby Medical School, Liverpool Medical School), clinical teaching begins in year 1 and makes the per capita formula inaccurate if not redundant.

Vertical integration of curriculum also creates the problem of jurisdiction. Who should pay for teaching students on a psychiatry placement learning about dual diagnosis in a primary care drug and alcohol clinic –should this be paid from the mental health trust SIFT income or from the primary care trust's SIFT income? A flat per capita system prevents the development of flexible teaching or teaching in a variety of settings best suited to students' learning needs and local resources and circumstances.

Direct funding

The Winyard report attempts to eliminate some of these distortions in SIFT funding by attempting to create a direct link between demonstrable activity and payment. 7 On the whole, there is broad support for this suggestion, although worries have been raised in some quarters that primarily Department of Health driven funding may increase the pressure on reducing medical training to technical training at the expense of ‘proper medical education’ and reduction in professionalism and professional status.

Mental health trusts are small players in the SIFT allocation but many trusts provide anything from 4 to 10 weeks of medical student placements. Reference Karim, Edwards, Dogra, Anderson, Davies and Lindsay14 To comply with General Medical Council's expectations there is also an increased need for psychiatrists to be involved in other aspects of the undergraduate curriculum such as communication skills. 15 There are also potential benefits for patients for psychiatrists and psychiatry to be integrated throughout the curriculum. However, who will pay for the non-direct but clinically relevant teaching? Integration may help reduce stigma that is still very prevalent. Reference Dogra, Edwards, Karim and Cavendish16 Medical students also emphasise the importance of clinical teachers playing an important part throughout their training rather than just being confined to the clinical placements. In the current political and economic climate with a squeeze on resources and ever-increasing targets, it is little surprise that medical education slips down in the trusts' priority agenda.

A scoping group initiative to clarify funding arrangements currently in place generated only three responses. Reference Dogra17 However, previous work highlighted it as an issue that causes considerable stress. Reference Dogra, Edwards, Karim and Cavendish16 The initiative was to try and support staff in ensuring that they are able to identify the resources required in delivering teaching and having effective educational strategies in place. It was also an opportunity to identify and share good practice. The poor response may in part be related to psychiatry leads having little clarity about funding and feeling that there is little good practice that can be shared in this area.

Case study

Derby Medical School is a new graduate entry medical school set up in 2003 to extend the intake of medical students at the University of Nottingham. Traditionally, only six students had their placements in Derby, but with the increased number of medical students this number has risen to 30. In the old SIFT funding set up, the mental health trust in Derby would have secured a fixed per capita cost for its six students. With the new SIFT money allocated for the new Derby Medical School (disbursed through East Midlands Strategic Health Authority and East Midlands Healthcare Workforce Deanery) the funding formula is linked to demonstrated costs (Fig. 1). Mental health trusts are usually too small to have direct funding from the Workforce Deanery and in the case of Derby Medical School (and South Derbyshire) funding is allocated by the medical school undergraduate resource group based at the acute trust in Derby. Having obtained its set funding from the Workforce Deanery, the resource group ensures equitable allocation of resources based on the quantity of the teaching programme. In practice, this means that the mental health trust, rather than getting a set amount of funding based on student weeks as a given, has to place bids with the resource group for identified teaching activity.

The resource group monitors that those contractual arrangements for agreed funding are robust and that there is an audit trail of all allocated resources. A regular process of review of allocations vis-à-vis educational contributions ensures education governance. Teaching quality is monitored by an independent group, teaching quality review group that assesses the quality of teaching as opposed to the medical school undergraduate resource group that uses quantitative measures in making allocations. However, the report of the teaching quality review group is fed to the resource group review process, thus influencing reallocation of resources.

The mental health trust has bid for and secured funding (salaries) for two half-time consultants to work as clinical teaching fellows, salary for one undergraduate administrator, salaries for two half-time nurse educators, funding for simulator patients, and funding to pay locum costs for general practitioners providing drug and alcohol services (to allow students to spend a day with the service). Other recurrent funding bids include bids for educational books and DVDs, contribution towards the salary of the trust librarian (in acknowledgement of the fact that the trust library is used by medical students) and for incidental expenses such as photocopying, travel and telephone costs. Non-recurrent bids include bids for building costs (of the new building shared by the trust and medical school), facilities and equipment (e.g. computers).

The end result is a spreadsheet with detailed accounts that allows an audit trail of monies obtained by the trust and spent on education-related activity. Further funding, for example for primary care-based nurse educator or sessions in primary care psychiatry, will have to be bid for and demonstrably linked to educational activity. An annual review attended by the clinical teaching fellows, the medical school undergraduate resource group representative and the trust financial director ensures that the sums are in order and also identifies any potential need for reallocation (e.g. alterations of costs in certain recurrent expenses). The teaching quality review group then monitors the quality of education provided through the use of these resources, based on various sources such as reports provided by the teaching fellows and student representatives, detailed feedback from students and overall consonance with the school curriculum.

The above model, ‘the demonstrated costs model’, is in contrast to the ‘melting pot model’ where the mental health trust receives a fixed sum per year that merges with the other income streams and the costs of facilitating teaching are assumed to equal the income received. In between these two lie the various models characterised by a nominated person or directorate to manage the SIFT funds with varying degrees of accountability. The pros and cons of each of these models are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Advantages and disadvantages of different funding models for medical education

| Model | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Demonstrated costs model | •Transparent | •Difficult to implement where there is no fresh money (e.g. if money has been disbursed among all consultants as an additional programmed activity) |

| •Flexible — allows local innovation | ||

| •Linked to educational outcomes — greater accountability | •Needs resources for monitoring and administration | |

| •Potentially greater than ‘usual’ income possible as income is linked to demonstrated costs | •Lack of proactive ‘bidding’ may lead to mental health trust losing out on their share | |

| Melting pot model | •Maintains status quo and therefore easy to administer | •Lack of transparency |

| •No drivers for innovation | ||

| •Fixed and assured income | •Inflexible as alteration can lead to serious problem with trust finances | |

| •Fixed income even if the actual costs of supporting education outstrip income | ||

| Nominated person or directorate | •Some degree of transparency | •Dependent on individual enthusiasm — lack of governance structures |

| •Accountability usually present though variable | •May be hostage to the priorities set by the nominated person or directorate |

The list in Table 1 is not exhaustive and the last group (nominated person or directorate) may include some very good or very bad examples of utilisation of SIFT funding. However, the first model does offer some significant advantages ensuring good educational governance with a transparent use of funds that can be linked to the quantity and quality of educational provision. The success of such practice has already been documented in other branches of medicine. Reference Badcock, Raj, Gadsby and Deighton18

Potential ways forward

Quality assurance is the cornerstone of improved educational governance, and accordingly, although not endorsing a particular model, we make a few suggestions that may help. The focus would be on quality assurance, robust leadership and greater transparency.

Quality assurance

Service increment for teaching funding is vital for NHS trusts to deliver medical student education, but trusts need to be accountable for the way SIFT money is spent. To this end, creating transparent financial and managerial structures is absolutely necessary to ensure that SIFT expenditure is used appropriately. Trusts could be penalised for not having clarity or transparency, as not to have these is poor clinical governance in terms of accountability.

Ideally, SIFT funds should be ring-fenced for medical student education. Even where this is not possible, SIFT expenses should be linked to actual medical student teaching activity. Procedures should be established so that an audit trail can be maintained to demonstrate that SIFT funds are spent directly on medical education. Medical student teaching needs to be explicitly defined in consultant job plans. Consultant psychiatrists tasked with the responsibility of organising medical student teaching (see below) will need clearly defined programmed activities to deliver on their role as medical student teaching leads. A medical student administrator is vital in dealing not only with student matters but also saves expensive consultant time by dealing with all teaching-related administrative issues. Similarly, SIFT funds can be innovatively bid for on-call rooms for medical students on the on-call rota or for IT facilities for medical students at the trust library.

Regular review of teaching quality can provide useful feedback about the robustness of the link between funding and teaching quality. With greater accountability becoming the norm within both the NHS and the university set up, educational governance assumes significant importance and trusts participating in medical student education need to set up mechanisms to deliver this.

Robust leadership

Those who lead medical education (whether they be of academic or clinical background) have a crucial role to play in liaising with SIFT providers, trust management and various colleagues who will help deliver clinical teaching to medical students.

Strong leadership is needed to ensure that psychiatry does not lose out to more technical disciplines such as surgery. Teaching psychiatric skills and attitudes to medical students is resource-intensive and may involve, for example, the use of actors or patient volunteers.

Conclusions

In summary, despite some advances, transparency around teaching budgets remains a challenge, both practically and conceptually. However, it should be anticipated that as transparency in SIFT funding improves, the vast majority of NHS mental health trusts with medical students will be able to reverse the historic bias of funding that favoured acute teaching hospitals. Reference Eagles19 The College is in a position to influence policy and to push forward an agenda for more transparency in resources for teaching psychiatry.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Tony Weetman, Dean, School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Sheffield and Chair, Education Sub-Committee of the Medical Schools' Council for his helpful comments on earlier drafts.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.