At a time of pandemics, international economic downturns, and increasing environmental threats due to climate change, countries around the world are facing numerous crises. What impact might we expect these crises to have on the already common perception that executive leadership is a masculine domain? For years, women executives’ ability to lead has been questioned (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). However, the outbreak of COVID-19 brought headlines like CNN’s “Women Leaders Are Doing a Disproportionately Great Job at Handling the Pandemic” (Fincher Reference Fincher2020). Do crises offer women presidents and prime ministers opportunities to be perceived as competent leaders? Or do they prime masculinized leadership expectations and reinforce common conceptions that women are unfit to lead? We maintain that people’s perceptions of crisis leadership will depend on whether the crisis creates role (in)congruity between traditional gender norms and the leadership expectations generated by the particular crisis.

What are Crises and How Do They Differ?

Following Lipscy (Reference Lipscy2020), we define a crisis as an exogenously caused disruption that poses a significant threat of harm to a country and necessitates an urgent political response. This definition resembles what Strolovitch (Reference Strolovitch, Remes and Horowitz2021, 53) calls “clear-cut crises” and differs from crises that are actually long-standing problems but become framed as crises only once they negatively affect privileged groups. While much of the literature on gender and crisis focuses on the inequitable effects of and policy response to a crisis on already marginalized groups such as women (e.g., Enarson Reference Enarson1998; O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2022; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2013), our discussion highlights the perception of women’s leadership in times of crisis. The high-stakes nature of crisis heightens the role of executives. Prime ministers and presidents, as the public face of the country, are generally expected to organize the government’s response. Even within the confines of this definition, however, crises can differ significantly. Crises vary by issue area and include, but are not limited to, economic, military, environmental, or public health crises.

In addition, urgency and ambiguity can fluctuate throughout a crisis. At certain points, the threat can be so severe that a rapid response is necessary. When immediate threats wane and conditions begin to stabilize, more time can be taken to respond. In some crises, the appropriate response may be straightforward, but, depending on the novelty of the situation, considerable ambiguity regarding the appropriate response may be present. The degree of ambiguity may also be higher earlier in the crisis. As recovery takes hold, conditions can allow for more deliberation on how to address long-term effects of the crisis. Thus, the nature of the crisis can vary.

Drawing on motivation language theory, we argue that leaders must employ three types of communication acts to foster trust in leadership (Mayfield and Mayfield Reference Mayfield and Mayfield2002, 91). First, a leader must employ “direction-giving language” that reduces crisis-generated ambiguity, sets specific goals, and clarifies what tasks need to be completed to overcome the crisis. Second, leaders must offer “empathetic language” that expresses their emotional understanding of the crisis’s costs to constituents, compassionately recognizing the human dimensions of the situation. Third, leaders must provide citizens with “meaning-making language,” placing the crisis and their response to it in the context of their country’s unique norms and values or historical experiences. Accordingly, if a leader can, over the course of the crisis, successfully deploy all three forms of rhetoric at the appropriate time, constituents are likely to trust and approve of the leader.

How Do Crises Intersect With Gender?

We argue that crises present both opportunity and risk for women leaders, depending on the characteristics of the crisis. Following the critical disaster studies literature, we believe that, just as gender is socially constructed, disasters are also socially constructed, political events (Horowitz and Remes Reference Horowitz, Jacob, Remes and Horowitz2021). The crisis issue area, the nature of the crisis, and the type of communication needed at a given time all intersect with a leader’s gender. According to social role theory, people expect certain behavior of individuals based on their personal characteristics (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). When it comes to gender roles and behavior, society and individuals hold specific assumptions regarding the appropriate social roles and behaviors for both women and men. Women are traditionally associated with communal skills (e.g., care, kindness, support) while men are linked to agentic skills (e.g., assertiveness, independence, competition). Further, gender roles (masculine and feminine) are seen as binary and hierarchical, meaning that one is seen as the norm (masculinity) and thus valued more than the other (femininity). Consequently, communal skills are linked to lower social status and roles, while agentic skills are linked to higher-status social roles. These social norms condition how we judge men and women leaders’ ability to handle crises.

The political domain has been constructed for men and by men, epitomized by the lack of women as prime ministers and presidents (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). Even in the absence of crisis, the presence of women in political leadership creates a social role incongruency that impacts the ways in which individuals evaluate and react to a woman leader’s performance (Rosette, Mueller, and Lebel Reference Rosette, Mueller and Lebel2015). Status incongruity describes the resistance that individuals experience when they act contrary to social role expectations (Rudman et al. Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012). Hence, women leaders do not operate in a vacuum; rather, their crisis leadership is judged against dominant societal gender roles and behaviors.

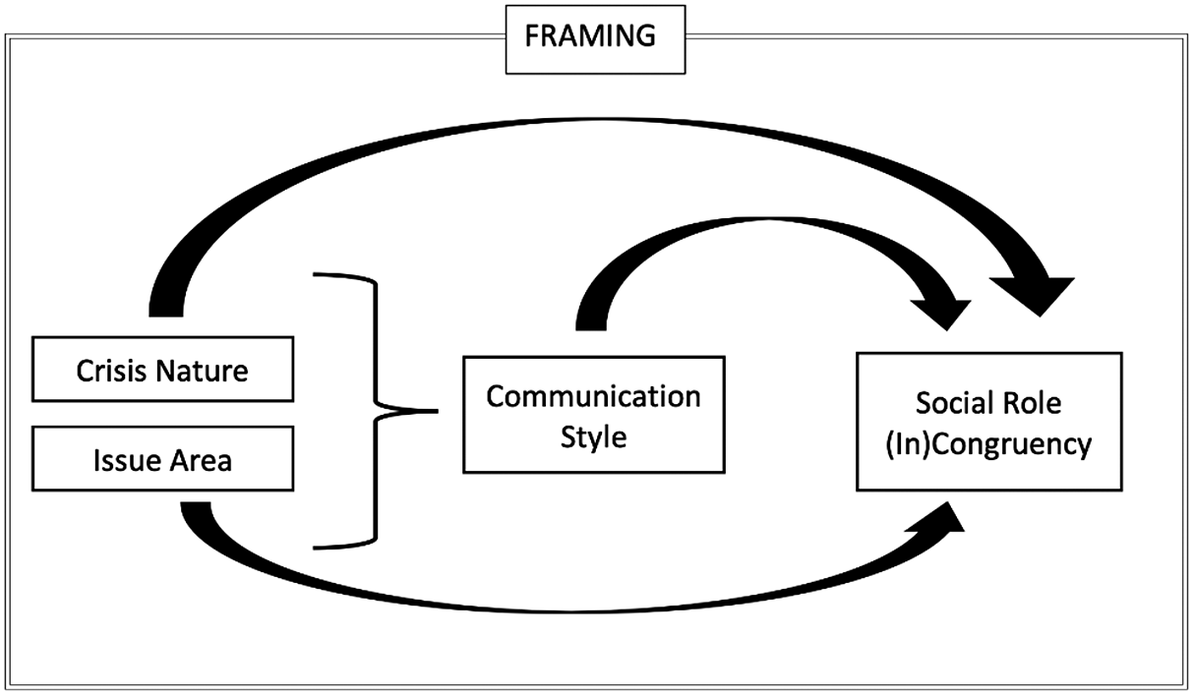

Next, we elaborate on how the crisis issue area, the crisis nature, and the communication type intersect with gender role expectations to produce different opportunities and challenges for men and women leaders (see Figure 1). Crises that produce social role congruency for women leaders will result in high approval ratings, creating greater long-term opportunities as they can demonstrate their fitness to lead. In contrast, whenever a crisis elicits role incongruence for women leaders, public approval will fall and fuel the narrative of “women as unfit leaders.” Men can exhibit communal skills and be praised for their sensitivity, while women leaders experience a double bind in which they can be neither too caring nor too agentic (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995). These (dis)advantages stem not from how well leaders actually respond to crisis but rather from how people perceive the leader’s performance. We argue that for men, social role incongruency does not elicit the same degree of backlash.

Figure 1. Relationship between crisis characteristics and social role congruence.

Given the possibility of social role (in)congruency, leaders might have incentives to shape how a particular crisis and their leadership style is perceived against dominant gendered norms. We expect that at certain times, leaders will have more opportunities to frame crises in a manner that creates social role congruency. However, a leader’s framing might compete with those of other actors, such as citizens, journalists, fellow politicians, or experts. The understanding that becomes dominant in the public arena can change social role (in)congruency for women in leadership.

Issue Area

Some issue areas are more commonly perceived as either masculine (e.g., security, economics) or feminine (e.g., health, environment) (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). When women leaders are confronted with a crisis in a traditional masculine policy realm, such as a terrorist attack, they will have a harder time creating social role congruency through crisis framing than in a policy domain that is traditionally perceived as feminine, such as a health crisis.

As noted, while men are less likely to experience social role incongruency because their fitness for leadership is automatically assumed unless proven otherwise, we expect that women leaders experience social role incongruency when confronted with a crisis that is framed in masculine terms. For example, Brazil’s economic crisis triggered Dilma Rousseff’s presidential impeachment in 2016. This crisis was a consequence of falling commodity prices and questionable polices that had begun under her predecessor, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, but continued during her administration. Yet most people only blamed Rousseff for the country’s recession, which was in progress when she came into office (though it certainly intensified during her tenure). In contrast, in 2020, New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern, like other women leaders worldwide, was hailed for her leadership during the COVID-19 health crisis. This crisis occurred in a feminized area and posed threats to the lives of countries’ weakest citizens—the elderly and infirm, for whom women are routinely expected to provide care.

Crisis Nature

When the appropriate policy response to a crisis appears clear, rapid and decisive leadership can be justified. Likewise, when a crisis leaves little time for deliberation and consultation, leaders are prompted to make unilateral decisions. Both scenarios benefit male leaders, as decisiveness is traditionally considered a male trait. In contrast, when a crisis is portrayed as a novel threat or ambiguity about the appropriate course of action is highlighted, there might be more opportunity for deliberation and consensus seeking. This process can make traditionally feminine traits such as caring, collaboration, and empathy salient, thus creating gender role congruency. Therefore, whenever a crisis is less urgent and allows for more deliberation and negotiation before making decisions, it more closely resonates with stereotypical feminine leadership traits of collaboration and consensus seeking.

For example, Brazil had often faced economic crises. Several previous presidents, including Lula (as well as governors and mayors), had developed a (questionable) budgetary procedure of borrowing money from state banks to fund national social programs. As president, Rousseff also used this procedure. When critics became aware that Rousseff unilaterally decided to engage in fiscal maneuvering that exacerbated the crisis, and that she did so over objections made by some of her party’s members, questions regarding her intelligence and overall leadership style surfaced. Both the issue area of the crisis (the economy) and Rousseff’s leadership style (unilateral, unambiguous) created a gender role incongruency that likely exacerbated the fallout Rousseff experienced. It is worth noting, however, that two days after Rousseff was officially removed from power, Brazil’s Senate legalized the very same fiscal move for which Rousseff was impeached, casting doubts that her impeachment and removal were truly motivated by efforts to protect Brazilian democracy, but rather steeped in and partially motivated by sexism.

In contrast, for women leaders, the COVID-19 pandemic created greater social role congruency. Because the crisis featured a previously unknown virus, ambiguity was high and national leaders were required to collaborate with scientists and health professionals to determine an appropriate response, stressing stereotypical feminine traits such as collaboration and caring. This gender role congruency allowed women leaders to emerge from the pandemic as admired and highly praised crisis managers, with New Zealand prime minister Ardern a case in point (Piscopo and Och 2021). She hosted regular “Conversations through COVID” on Facebook and Instagram Live, during which she invited experts to discuss issues such as mental health and to answer questions about the pandemic (Tworek, Beacock, and Ojo Reference Tworek, Beacock and Ojo2020).

Communication Style

Leaders navigate the types of communication styles to employ in a given situation. However, when women leaders decide on their communication strategy, they must be more aware of social gender expectations and how their communication style will be perceived. Direction-giving language is agentic, consistent with masculine social roles. When men leaders provide this kind of direction, they are viewed as acting in accordance with prevailing gender norms and, in turn, likely to be perceived as effective leaders. Conversely, when women leaders employ direction-giving language, they are acting at odds with social expectations of feminine behavior. Individuals deviating from prevailing gender norms are evaluated less favorably, making it more difficult for women leaders to maneuver without provoking negative reactions on the part of constituents.

Empathetic language, the second element of successful crisis management, is more consistent with feminine norms and women leaders are socially rewarded for employing this type of rhetoric. Likewise, when men fail to express empathy, it is not considered a flaw and if they do express empathy, it often is positively received.

The third type of crisis leadership, the use of meaning-making language, is less clearly connected to prevailing gender stereotypes. National contexts offer multiple norms and values upon which heads of state and government can draw when trying to create meaningful narratives about the appropriate response to crisis. Here, both men and women leaders enjoy the freedom to select language that is consistent with social role expectations.

In the case of Brazil, political elites, including members of Rousseff’s own disintegrating government coalition, repeatedly attacked Rousseff and accused her of being overly aggressive and harsh when she addressed the public and political elites using direction-giving language. Another common accusation was that she opted to escalate conflict rather than seek compromise or consensus (dos Santos and Jalalzai Reference dos Santos and Jalalzai2021). Rousseff unliterally implemented an aggressive fiscal adjustment and refused to admit any wrongdoing or mistakes. Her actions created a significant social role incongruency, since bullish and decisive communication and a unilateral decision-making style are most commonly associated with masculine traits.

In contrast, empathetic language was required to assuage the mental health crisis accompanying the global COVID-19 lockdown, creating gender role congruency for women leaders. Ardern’s leadership style was dubbed a “politics of kindness” and centered on a message of coming together, referring to New Zealand as “our team of five million” (Piscopo and Och Reference Piscopo and Och2021). Her ability to humanize the challenges of the pandemic endeared her to many Kiwis. The same social role congruency held for other women leaders, such as German chancellor Angela Merkel and Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg, who also benefited from the public’s need to be reassured. Merkel was praised for her ability to express empathy and recognize the hardships imposed by the crisis, while Solberg’s direct communication with children about the pandemic generated much admiration at home and abroad (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2020; Piscopo and Och Reference Piscopo and Och2021).

Conclusion

The foregoing observations combine to generate a variety of social role (in)congruencies for leaders. Depending on the issue area, the nature of the crisis, and the communication style required of a national leader, men and women are placed in different positions of advantage or disadvantage. Challenged by a (masculinized) economic crisis, unilaterally relying on an established but questionable budgetary procedure, and employing direction-giving language, Dilma Rousseff’s approval ratings plunged, and she was impeached. Jacinda Ardern, in contrast, faced a (feminized) health crisis, had time to seek expert advice about how to combat an ambiguous threat, and could utilize empathetic language to comfort citizens. Her popularity soared and her constituents handed her party a resounding victory in the 2020 election.

Crises, therefore, are not uniform but differ in the way the crisis is framed (crisis type), the extent of ambiguity (crisis nature) surrounding the crisis, and the type of communication employed (communication style). When these three factors come together to produce gender role congruency for women leaders, their leadership is likely to be evaluated positively, enhancing their hold on political power. In contrast, crises can also create gender role incongruity for women leaders, exacerbating backlash and reinforcing the masculinization of executive office.

At a time of pandemics, international economic downturns, and increasing environmental threats due to climate change, countries around the world are facing numerous crises. What impact might we expect these crises to have on the already common perception that executive leadership is a masculine domain? For years, women executives’ ability to lead has been questioned (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). However, the outbreak of COVID-19 brought headlines like CNN’s “Women Leaders Are Doing a Disproportionately Great Job at Handling the Pandemic” (Fincher Reference Fincher2020). Do crises offer women presidents and prime ministers opportunities to be perceived as competent leaders? Or do they prime masculinized leadership expectations and reinforce common conceptions that women are unfit to lead? We maintain that people’s perceptions of crisis leadership will depend on whether the crisis creates role (in)congruity between traditional gender norms and the leadership expectations generated by the particular crisis.

What are Crises and How Do They Differ?

Following Lipscy (Reference Lipscy2020), we define a crisis as an exogenously caused disruption that poses a significant threat of harm to a country and necessitates an urgent political response. This definition resembles what Strolovitch (Reference Strolovitch, Remes and Horowitz2021, 53) calls “clear-cut crises” and differs from crises that are actually long-standing problems but become framed as crises only once they negatively affect privileged groups. While much of the literature on gender and crisis focuses on the inequitable effects of and policy response to a crisis on already marginalized groups such as women (e.g., Enarson Reference Enarson1998; O’Dwyer Reference O’Dwyer2022; Strolovitch Reference Strolovitch2013), our discussion highlights the perception of women’s leadership in times of crisis. The high-stakes nature of crisis heightens the role of executives. Prime ministers and presidents, as the public face of the country, are generally expected to organize the government’s response. Even within the confines of this definition, however, crises can differ significantly. Crises vary by issue area and include, but are not limited to, economic, military, environmental, or public health crises.

In addition, urgency and ambiguity can fluctuate throughout a crisis. At certain points, the threat can be so severe that a rapid response is necessary. When immediate threats wane and conditions begin to stabilize, more time can be taken to respond. In some crises, the appropriate response may be straightforward, but, depending on the novelty of the situation, considerable ambiguity regarding the appropriate response may be present. The degree of ambiguity may also be higher earlier in the crisis. As recovery takes hold, conditions can allow for more deliberation on how to address long-term effects of the crisis. Thus, the nature of the crisis can vary.

Drawing on motivation language theory, we argue that leaders must employ three types of communication acts to foster trust in leadership (Mayfield and Mayfield Reference Mayfield and Mayfield2002, 91). First, a leader must employ “direction-giving language” that reduces crisis-generated ambiguity, sets specific goals, and clarifies what tasks need to be completed to overcome the crisis. Second, leaders must offer “empathetic language” that expresses their emotional understanding of the crisis’s costs to constituents, compassionately recognizing the human dimensions of the situation. Third, leaders must provide citizens with “meaning-making language,” placing the crisis and their response to it in the context of their country’s unique norms and values or historical experiences. Accordingly, if a leader can, over the course of the crisis, successfully deploy all three forms of rhetoric at the appropriate time, constituents are likely to trust and approve of the leader.

How Do Crises Intersect With Gender?

We argue that crises present both opportunity and risk for women leaders, depending on the characteristics of the crisis. Following the critical disaster studies literature, we believe that, just as gender is socially constructed, disasters are also socially constructed, political events (Horowitz and Remes Reference Horowitz, Jacob, Remes and Horowitz2021). The crisis issue area, the nature of the crisis, and the type of communication needed at a given time all intersect with a leader’s gender. According to social role theory, people expect certain behavior of individuals based on their personal characteristics (Eagly and Karau Reference Eagly and Karau2002). When it comes to gender roles and behavior, society and individuals hold specific assumptions regarding the appropriate social roles and behaviors for both women and men. Women are traditionally associated with communal skills (e.g., care, kindness, support) while men are linked to agentic skills (e.g., assertiveness, independence, competition). Further, gender roles (masculine and feminine) are seen as binary and hierarchical, meaning that one is seen as the norm (masculinity) and thus valued more than the other (femininity). Consequently, communal skills are linked to lower social status and roles, while agentic skills are linked to higher-status social roles. These social norms condition how we judge men and women leaders’ ability to handle crises.

The political domain has been constructed for men and by men, epitomized by the lack of women as prime ministers and presidents (Jalalzai Reference Jalalzai2013). Even in the absence of crisis, the presence of women in political leadership creates a social role incongruency that impacts the ways in which individuals evaluate and react to a woman leader’s performance (Rosette, Mueller, and Lebel Reference Rosette, Mueller and Lebel2015). Status incongruity describes the resistance that individuals experience when they act contrary to social role expectations (Rudman et al. Reference Rudman, Moss-Racusin, Phelan and Nauts2012). Hence, women leaders do not operate in a vacuum; rather, their crisis leadership is judged against dominant societal gender roles and behaviors.

Next, we elaborate on how the crisis issue area, the crisis nature, and the communication type intersect with gender role expectations to produce different opportunities and challenges for men and women leaders (see Figure 1). Crises that produce social role congruency for women leaders will result in high approval ratings, creating greater long-term opportunities as they can demonstrate their fitness to lead. In contrast, whenever a crisis elicits role incongruence for women leaders, public approval will fall and fuel the narrative of “women as unfit leaders.” Men can exhibit communal skills and be praised for their sensitivity, while women leaders experience a double bind in which they can be neither too caring nor too agentic (Jamieson Reference Jamieson1995). These (dis)advantages stem not from how well leaders actually respond to crisis but rather from how people perceive the leader’s performance. We argue that for men, social role incongruency does not elicit the same degree of backlash.

Figure 1. Relationship between crisis characteristics and social role congruence.

Given the possibility of social role (in)congruency, leaders might have incentives to shape how a particular crisis and their leadership style is perceived against dominant gendered norms. We expect that at certain times, leaders will have more opportunities to frame crises in a manner that creates social role congruency. However, a leader’s framing might compete with those of other actors, such as citizens, journalists, fellow politicians, or experts. The understanding that becomes dominant in the public arena can change social role (in)congruency for women in leadership.

Issue Area

Some issue areas are more commonly perceived as either masculine (e.g., security, economics) or feminine (e.g., health, environment) (Krook and O’Brien Reference Krook and O’Brien2012). When women leaders are confronted with a crisis in a traditional masculine policy realm, such as a terrorist attack, they will have a harder time creating social role congruency through crisis framing than in a policy domain that is traditionally perceived as feminine, such as a health crisis.

As noted, while men are less likely to experience social role incongruency because their fitness for leadership is automatically assumed unless proven otherwise, we expect that women leaders experience social role incongruency when confronted with a crisis that is framed in masculine terms. For example, Brazil’s economic crisis triggered Dilma Rousseff’s presidential impeachment in 2016. This crisis was a consequence of falling commodity prices and questionable polices that had begun under her predecessor, Luiz Inácio “Lula” da Silva, but continued during her administration. Yet most people only blamed Rousseff for the country’s recession, which was in progress when she came into office (though it certainly intensified during her tenure). In contrast, in 2020, New Zealand prime minister Jacinda Ardern, like other women leaders worldwide, was hailed for her leadership during the COVID-19 health crisis. This crisis occurred in a feminized area and posed threats to the lives of countries’ weakest citizens—the elderly and infirm, for whom women are routinely expected to provide care.

Crisis Nature

When the appropriate policy response to a crisis appears clear, rapid and decisive leadership can be justified. Likewise, when a crisis leaves little time for deliberation and consultation, leaders are prompted to make unilateral decisions. Both scenarios benefit male leaders, as decisiveness is traditionally considered a male trait. In contrast, when a crisis is portrayed as a novel threat or ambiguity about the appropriate course of action is highlighted, there might be more opportunity for deliberation and consensus seeking. This process can make traditionally feminine traits such as caring, collaboration, and empathy salient, thus creating gender role congruency. Therefore, whenever a crisis is less urgent and allows for more deliberation and negotiation before making decisions, it more closely resonates with stereotypical feminine leadership traits of collaboration and consensus seeking.

For example, Brazil had often faced economic crises. Several previous presidents, including Lula (as well as governors and mayors), had developed a (questionable) budgetary procedure of borrowing money from state banks to fund national social programs. As president, Rousseff also used this procedure. When critics became aware that Rousseff unilaterally decided to engage in fiscal maneuvering that exacerbated the crisis, and that she did so over objections made by some of her party’s members, questions regarding her intelligence and overall leadership style surfaced. Both the issue area of the crisis (the economy) and Rousseff’s leadership style (unilateral, unambiguous) created a gender role incongruency that likely exacerbated the fallout Rousseff experienced. It is worth noting, however, that two days after Rousseff was officially removed from power, Brazil’s Senate legalized the very same fiscal move for which Rousseff was impeached, casting doubts that her impeachment and removal were truly motivated by efforts to protect Brazilian democracy, but rather steeped in and partially motivated by sexism.

In contrast, for women leaders, the COVID-19 pandemic created greater social role congruency. Because the crisis featured a previously unknown virus, ambiguity was high and national leaders were required to collaborate with scientists and health professionals to determine an appropriate response, stressing stereotypical feminine traits such as collaboration and caring. This gender role congruency allowed women leaders to emerge from the pandemic as admired and highly praised crisis managers, with New Zealand prime minister Ardern a case in point (Piscopo and Och 2021). She hosted regular “Conversations through COVID” on Facebook and Instagram Live, during which she invited experts to discuss issues such as mental health and to answer questions about the pandemic (Tworek, Beacock, and Ojo Reference Tworek, Beacock and Ojo2020).

Communication Style

Leaders navigate the types of communication styles to employ in a given situation. However, when women leaders decide on their communication strategy, they must be more aware of social gender expectations and how their communication style will be perceived. Direction-giving language is agentic, consistent with masculine social roles. When men leaders provide this kind of direction, they are viewed as acting in accordance with prevailing gender norms and, in turn, likely to be perceived as effective leaders. Conversely, when women leaders employ direction-giving language, they are acting at odds with social expectations of feminine behavior. Individuals deviating from prevailing gender norms are evaluated less favorably, making it more difficult for women leaders to maneuver without provoking negative reactions on the part of constituents.

Empathetic language, the second element of successful crisis management, is more consistent with feminine norms and women leaders are socially rewarded for employing this type of rhetoric. Likewise, when men fail to express empathy, it is not considered a flaw and if they do express empathy, it often is positively received.

The third type of crisis leadership, the use of meaning-making language, is less clearly connected to prevailing gender stereotypes. National contexts offer multiple norms and values upon which heads of state and government can draw when trying to create meaningful narratives about the appropriate response to crisis. Here, both men and women leaders enjoy the freedom to select language that is consistent with social role expectations.

In the case of Brazil, political elites, including members of Rousseff’s own disintegrating government coalition, repeatedly attacked Rousseff and accused her of being overly aggressive and harsh when she addressed the public and political elites using direction-giving language. Another common accusation was that she opted to escalate conflict rather than seek compromise or consensus (dos Santos and Jalalzai Reference dos Santos and Jalalzai2021). Rousseff unliterally implemented an aggressive fiscal adjustment and refused to admit any wrongdoing or mistakes. Her actions created a significant social role incongruency, since bullish and decisive communication and a unilateral decision-making style are most commonly associated with masculine traits.

In contrast, empathetic language was required to assuage the mental health crisis accompanying the global COVID-19 lockdown, creating gender role congruency for women leaders. Ardern’s leadership style was dubbed a “politics of kindness” and centered on a message of coming together, referring to New Zealand as “our team of five million” (Piscopo and Och Reference Piscopo and Och2021). Her ability to humanize the challenges of the pandemic endeared her to many Kiwis. The same social role congruency held for other women leaders, such as German chancellor Angela Merkel and Norwegian prime minister Erna Solberg, who also benefited from the public’s need to be reassured. Merkel was praised for her ability to express empathy and recognize the hardships imposed by the crisis, while Solberg’s direct communication with children about the pandemic generated much admiration at home and abroad (Davidson-Schmich Reference Davidson-Schmich2020; Piscopo and Och Reference Piscopo and Och2021).

Conclusion

The foregoing observations combine to generate a variety of social role (in)congruencies for leaders. Depending on the issue area, the nature of the crisis, and the communication style required of a national leader, men and women are placed in different positions of advantage or disadvantage. Challenged by a (masculinized) economic crisis, unilaterally relying on an established but questionable budgetary procedure, and employing direction-giving language, Dilma Rousseff’s approval ratings plunged, and she was impeached. Jacinda Ardern, in contrast, faced a (feminized) health crisis, had time to seek expert advice about how to combat an ambiguous threat, and could utilize empathetic language to comfort citizens. Her popularity soared and her constituents handed her party a resounding victory in the 2020 election.

Crises, therefore, are not uniform but differ in the way the crisis is framed (crisis type), the extent of ambiguity (crisis nature) surrounding the crisis, and the type of communication employed (communication style). When these three factors come together to produce gender role congruency for women leaders, their leadership is likely to be evaluated positively, enhancing their hold on political power. In contrast, crises can also create gender role incongruity for women leaders, exacerbating backlash and reinforcing the masculinization of executive office.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Jennifer Piscopo, Diana Z. O’Brien, anonymous reviewers, and commentators on our 2021 panel at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association for useful feedback on this essay.