Melatonin ( n -acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) is widely prescribed in child psychiatric practice for symptomatic treatment of ’insomnia’ in the UK (Reference Armour and PatonArmour & Paton, 2004; Reference Waldron and BrambleWaldron et al, 2005) and perhaps in several other countries of western Europe despite the paucity of evidence of its long-term safety and some vagary of its clinical usefulness in children and adolescents. In this article we examine the propriety of its use in the light of more recent studies and propose guidelines pending valid definition of its pharmacotherapeutic status.

Method

With keywords, melatonin, circadian rhythm, child and adolescents, we searched two databases namely MEDLINE and the Educational Resources Information Centre (ERIC) for ’any publications’: journal articles, research reports and monographs, for the period 1950–2007. Cochrane Library reviews were perused for additional information on the effect of melatonin on jet lag (Reference Herxheimer and PetrieHerxheimer & Petrie, 2002) and related themes. Our searches yielded 168 hits out of which 33 have hard-core neurobiological content and with their insignificant relevance to our clinical interest they were excluded. The remaining 135 papers (inclusive of 57 duplications) on clinical trials and systemic analyses that specifically addressed the use of melatonin in paediatric and psychiatric practice were critically reviewed. We endeavoured to cover a wide bibliography but we might have missed some non-English publications as well as those that did not fit into the classified subheadings (search grouping of keywords).

Mode of action

Melatonin is the major hormone of the pineal gland produced from the amino acid tryptophan and it is known from animal studies (Reference ArmstrongArmstrong, 1989; Reference Bartness and GoldmanBartness & Goldman, 1989; Reference Rusak and BinaRusak & Bina, 1990) to elevate the concentration of aminobutyric acid, dopamine and serotonin in the mid-brain and hypothalamus.

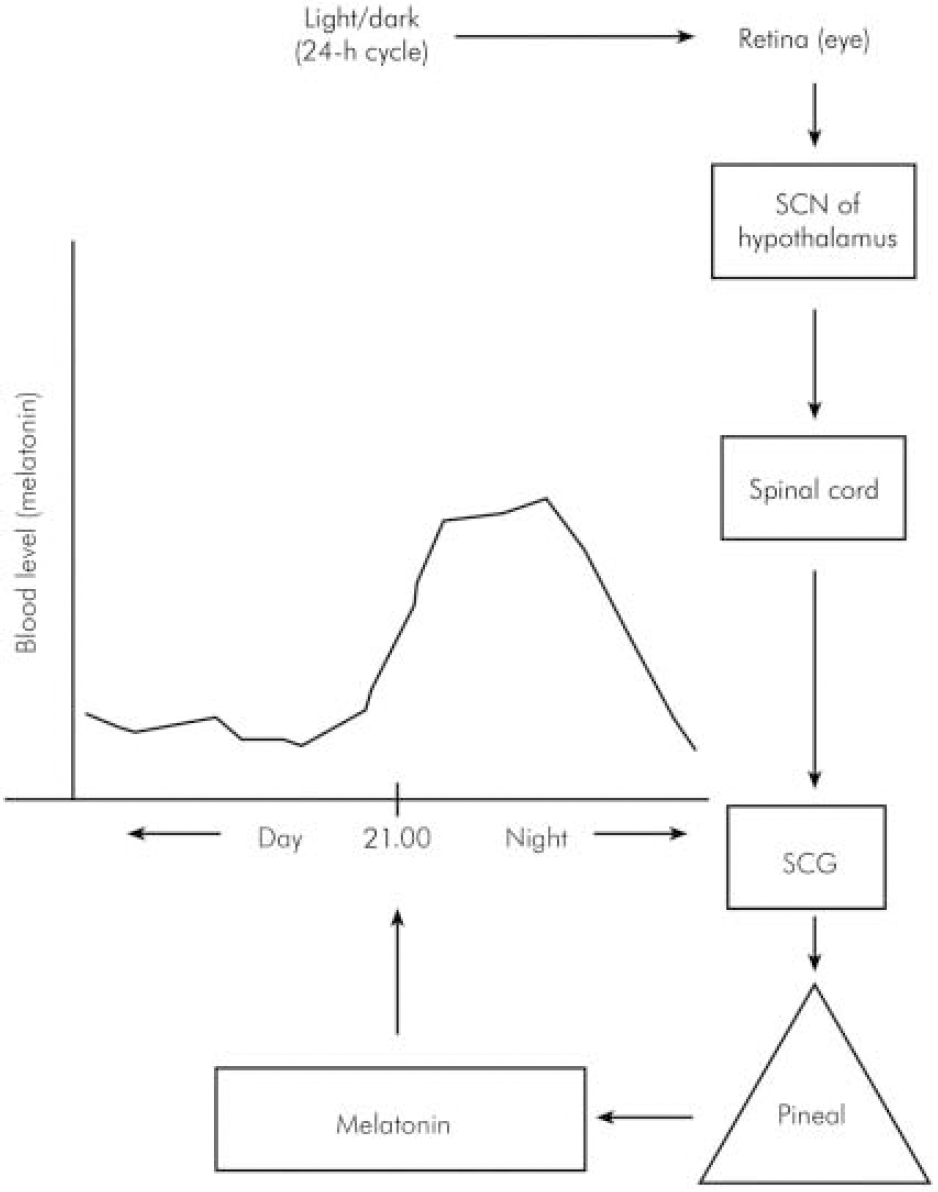

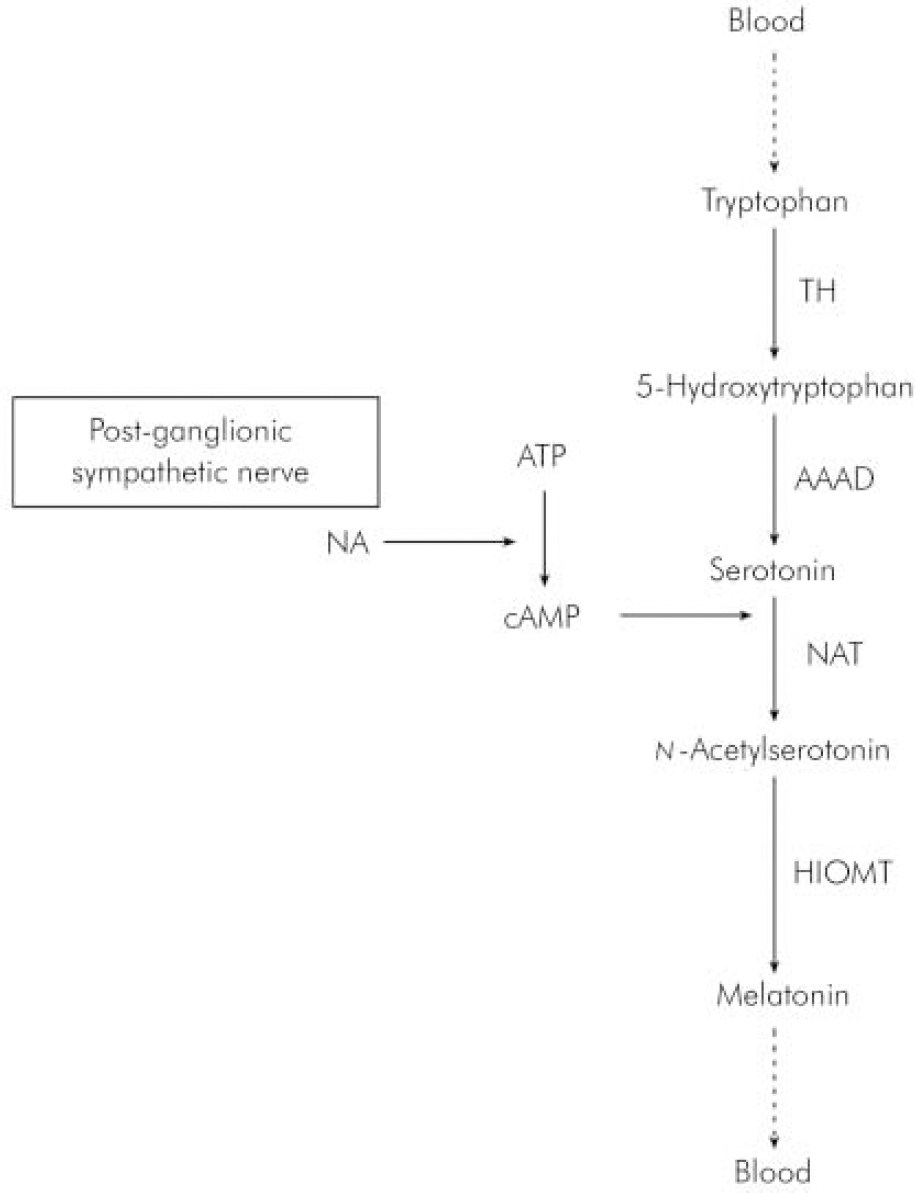

In humans, melatonin is synthesised from serotonin in a reaction that is entrained to the light–dark 24 h cycle (Reference BrzezinskiBrzezinski, 1997) via a neural pathway from the eye relaying in the suprachiasmatic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus then descending to the thoracic spinal cord and superior cervical ganglion to innervate the pineal gland (Reference Moller, Ravault and CozziMoller et al, 1996) (Fig. 1). At night, its production is stimulated by noradrenaline released by post-ganglionic sympathetic nerve fibres from the superior ganglia and through cyclic adenosine monophospate (cAMP) norardrenaline stimulates the synthesis and activity of n -acetyl transferase, which is one of the major enzymes involved in the synthesis of melatonin (Fig. 2). During the daytime, light suppresses norardrenaline release by the post-ganglionic sympathetic nerve fibres innervating the pineal gland and melatonin synthesis decreases (Reference WebbWebb & Puig-Domingo, 1995). Therefore, melatonin secretion has a diurnal pattern with blood level rising around 21.00 h and remaining elevated for 12 h then receding to a trough during the daytime.

Fig. 1. Schematic neural link between the pineal gland and the light–dark environment. SCN, suprachiasmatic nucleus; SCG, superior cervical ganglion.

Pharmacotherapy

A major limitation of the appraisal of the effect of melatonin on sleep was the failure of several authors to explicitly define insomnia. Furthermore, different definitions focused on different aspects of sleep pathology such as disturbance of: initiation, sustenance, termination or poor quality. However, it would appear that, generally, the term is used in a generic sense to mean difficulty in falling asleep or remaining asleep or poor quality sleep.

Regarding clinical benefit, there is evidence that one of the main actions of melatonin is reduction of sleep-onset latency, i.e. duration of time falling asleep (Reference Zhdanova, Wurtman and LynchZhdanova et al, 1995; Reference Nagtegaal, Laurant and Kerki-IofNagtegaal et al, 2000) and this feature, which is a component of its diurnal secretory pattern, constitutes the basis of its use in the treatment of insomnia owing to altered light–dark circadian rhythm such as occurs in jet lag (Reference Herxheimer and PetrieHerxheimer & Petrie, 2002). However, a rigorous and more recent systematic review (Reference Buscemi, Vandermeer and HootonBuscemi et al, 2006) concludes that exogenous melatonin did not exert significant effect on jet lag or shift work in adults. Stimulated by studies on adults, considerable attention has been paid in the past decade to clinical utility in child mental healthcare. Details of the most recent systematic studies of melatonin use in children and adolescents can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Clinical trials of melatonin in children and adolescents1

| Author(s) | Type of study | Sample size, n | Age, years | Diagnosis | Dose, mg | Duration | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Heijden, et al (Reference Van Der Heijden, Smits and Van Someren2007) | Randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled | 105 | 6-12 | ADHD | 3 or 6 | 4 weeks | Increased total sleep duration |

| Gianotti, et al (2006) | Controlled | 25 | 2.5-9.5 | Autism | 5 | 24 weeks | Sleep improved in all participants |

| Weiss, et al (Reference Weiss, Wasdell and Bomben2006) | Randomised, placebo-controlled | 27 | 6-14 | ADHD | 5 | 30 days | Effective in all participants (+sleep hygiene) |

| Smits, et al (Reference Smits, Van Stel and Vander Heijden2003) | Randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled | 62 | 6-12 | Idiopathic insomnia | 5 | 4 weeks | Better than placebo |

| Camfield et al (Reference Camfield, Gordon and Dooley1996) | Controlled | 6 | 6-12 | Developmental disorders | 0.5-1 | 4 weeks | None improved |

| Coppola, et al (Reference Coppola, Iervolino and Mastrosimone2004) | Randomised, double-blind placebo-controlled | 25 | 4-26 | Intellectual disability+epilepsy | 3-9 | 8 weeks | Significant improvement |

| Tjon Pian Gi, et al (2003) | Open label uncontrolled | 24 | Not stated | ADHD | 3 | 12 weeks | Significantly effective |

| Szeinberg, et al (Reference Szeinberg, Borodkin and Dagan2006) | Retrospective | 33 | 10-18 | Delayed sleep-phase syndrome | 3-5 | 24 weeks | Significant improvement |

For instance, melatonin was found in a placebo-controlled trial to be effective in improving delayed sleep-onset unassociated with a specific disorder in children (Reference Smits, Van Stel and Vander HeijdenSmits et al, 2003) and in adolescents (Reference Szeinberg, Borodkin and DaganSzeinberg et al, 2006). A similar finding was obtained in relation to sleep-onset disorder in a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders such as autism (Reference Giannotti, Cortesi and CerquiglinGiannotti et al, 2006), multiple disabilities (Reference Sajith and ClarkeSajith & Clarke, 2007), neurodevelopmental disabilities (Reference Phillips and AppletonPhillips & Appleton, 2004) and intellectual disability (Reference JanJan, 2000; Reference Coppola, Iervolino and MastrosimoneCoppola et al, 2004). However, it should be borne in mind that the clinical features of these underlying disorders in the studies might mask veritable side-effects and, moreover, the dose of melatonin varied considerably – a point highlighted in a survey of prescribing practices of paediatricians that found doses ranging widely from 0.5 mg to 24 mg (Reference Waldron and BrambleWaldron et al, 2005). Furthermore, lack of control and the fact that efficacy (i.e. the extent to which a drug produced the desired therapeutic effect) was assessed in the short term, such that a placebo response (the law of initial effect) could contribute significantly to a false positive outcome.

Fig. 2. Synthesis of melatonin in the pineal gland. AAAD, 1-aromatic-aminoacid-decarboxylase; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; cAMP, cyclic adenosine monophospate; HIOMT, hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase; NA, noradrenaline; NAT, n-acetyltransferase; TH, tyroxine hydroxylase.

Some other studies (Tjon Pian Gi et al, 2003; Reference Golan, Sharshar and RavidGolan et al, 2004) highlighted the usefulness of melatonin in control of prolonged sleep-latency known to be the most common sleep disturbance in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Reference Barkley, McMurray and EdelbrockBarkley et al, 1990) and not surprisingly, therefore, prescription of sleep medication was found to be two- to fourfold more frequent in children with this disorder than in those without (Reference Owens, Rosen and MindellOwens et al, 2003). A related issue that should be considered in an evaluation of the effect of melatonin in ADHD is the fact that stimulant medication can further increase initial insomnia (Reference Schwartz, Amor and GrizenkoSchwartz et al, 2004).

Reviewing the evidence findings on clinical benefit from randomised placebo-controlled studies (Reference Weiss, Wasdell and BombenWeiss et al, 2006; Reference Van Der Heijden, Smits and Van SomerenVan der Heijden et al, 2007) favour the inference that melatonin is effective in treating sleep-onset insomnia in ADHD and may be useful in this type of insomnia associated with a variety of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Dose and side-effects

The therapeutic dose in children and adolescents is yet to be determined by consensus; consequently, doses vary significantly among clinicians. The initial dose generally recommended is 2–3 mg to be taken half an hour before usual bedtime and can be increased 4–6 mg if there was no benefit after 2 weeks. The maximum dose should not exceed 10 mg. Regular review is important and a decision on the desirability of continued administration should be taken after 6 months.

A major issue for due consideration is the intensity and protean pharmacological actions of melatonin which involves multiple organ systems. For example, it modulates immune functions (Reference Besedovsky and ReyBesedovsky & Rey, 1996; Reference Sutherland, Martin and EllisonSutherland et al, 2003), inhibits gonadal activity (Reference WeaverWeaver, 1997), is a powerful antioxidant and a free radical scavenger (Reference Pierie, Marra and MoroniPierie et al, 1994), may have oncostatic properties (Reference LambergLamberg, 1996) and because of its reciprocal relationship to β-adrenergic receptor activity, may worsen depression in some individuals (Reference PeselowPeselow, 2005).

We found no single study that reported any significant side-effects of melatonin in the short term, but it is pertinent to note that among the controlled clinical trials in the past 20 years or so, the longest follow-up evaluation period in a study (Reference Giannotti, Cortesi and CerquiglinGiannotti et al, 2006) was 24 weeks, a finding which obviously can diminish confidence regarding the safety of long-term prescribing. However, from anecdotal evidence, three side-effects, epileptiform seizures in neurologically disordered children (Reference SheldonSheldon, 1998), asthmatic attacks (Reference Sutherland, Martin and EllisonSutherland et al, 2003) and contraceptive effect (Reference WeaverWeaver, 1997), have been recognised.

Another point of note is that theoretically the wide pharmacological action spectrum indicated above, which is attributable to multiplicity of active sites, as with hormones in general, constitutes significant potential for probable side-effects.

Sleep hygiene

In view of the uncertainty of long-term side-effects, some attention should be paid to the application of sleep hygiene defined as the ‘regulation of those daily activities and environmental factors consistent with the maintenance of good quality sleep and daytime alertness’ (American Sleep Disorders Association, 1997). The key rules of sleep hygiene include: sleeping on a comfortable bed in a cool and quiet room, regular sleep time scheduling, avoidance of stimulants and late night recreations (e.g. television and computer games and for children this should be supported by positive reinforcements by parents).

As a sole treatment in young adults, sleep hygiene was not found to be as effective as other treatments (Reference Morin, Culbert and SchwartzMorin et al, 1994). Interestingly, in a study of adults, there was no difference in knowledge about sleep hygiene in good sleepers compared with people with insomnia and in people with insomnia engaged in more unhealthy habits than good sleepers (Reference Lacks and RotertsLacks & Roterts, 1986). Unfortunately, controlled studies that compare sleep hygiene with pharmacological treatment in children are very few.

A recent randomised, placebo-controlled trial (Reference Weiss, Wasdell and BombenWeiss et al, 2006) investigated the relative merits of melatonin (dose 5 mg) and sleep hygiene for delayed sleep-onset insomnia in children and adolescents, (average age 10.4 years, range 6.5–14.7) with ADHD who were on stimulants. Sleep was evaluated with use of actigraphy (a process of continuing monitoring of body movements and other indicators of quantity and quality of sleep) and somnolog (a detailed structured record of sleep pattern). The authors concluded that melatonin was clinically superior to placebo in decreasing sleep-onset latency and that a combination of sleep hygiene and melatonin could obviate the need for a hypnotic.

Availability

Finally, in the USA, melatonin is the only hormone available without a prescription and its sale as a food supplement is allowed legally but manufacturing procedures are not standardised so that the dose in each tablet varies between packages. In current clinical practice, melatonin is administered orally only and the two major formulations are immediate release and extended release. Several strengths varying from 1.0 mg to 7.5 mg are available and the most common presentations include tablets, capsules, sublingual lozenges and liquid. In the UK, the Medicines and Health Care Regulatory Agency has declared melatonin a medicinal product rather than a nutritional supplement hence over-the-counter dispensing is not permitted and it is yet to be licensed. However, its popularity apparently predicates on the reported clinical effectiveness in sleep-onset disturbance coupled with the fact that no significant side-effects in the short term have been reported, but the non-existence of agreed posological guidelines remains a problem in clinical practice in that it can result in under-treatment or overdosing.

Conclusion

There is evidence that melatonin is effective in the control of delayed sleep-onset as a primary problem or associated with some neuropsychiatric disorders; but it should be prescribed judiciously and combined with sleep hygiene so that optimum results can be achieved (Reference Weiss, Wasdell and BombenWeiss et al, 2006). To date, no serious side-effects have been reported. None the less, clinicians should be mindful of the possibility of fatal side-effects with prolonged use.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.