LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the core clinical features and key aetiological factors of BPD

• confidently diagnose BPD using a structured history-taking approach

• recognise comorbid conditions when they occur and, where possible, distinguish BPD from disorders with shared clinical features.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a contested diagnosis for a number of reasons: the phenotype is heterogeneous, there is extensive symptom overlap with other psychiatric diagnoses and debate about the validity of the BPD diagnosis in the literature. However, as a diagnostic construct, like many in psychiatry, it provides an important working concept for clinicians and a framework for organising clinical experience and treatment planning (Jablensky Reference Jablensky2016). BPD is the most widely researched personality disorder (Blashfield Reference Blashfield and Intoccia2000), which has informed the development of a treatment evidence base. Therefore, the diagnosis has pragmatic utility in supporting the identification of those who may respond to particular interventions. This is important since BPD is overrepresented in healthcare settings and individuals with a BPD diagnosis report significant difficulty accessing effective and consistent care and feeling understood by healthcare professionals (Lawn Reference Lawn and McMahon2015). Here we suggest an approach to performing a comprehensive clinical assessment to elicit core diagnostic features with a view to informing a holistic care plan.

Classification

The BPD diagnosis has long garnered controversy in terms of its conceptual and diagnostic validity. The diagnosis itself was created by expert committee without an empirical foundation, and research on its classification remains scant (Tyrer Reference Tyrer, Mulder and Kim2019). Despite this, it is argued that the diagnosis has clinical utility and has been an important driver of research and therapeutic developments.

Much debate and dissatisfaction hinges on the classification systems of personality disorder, in particular the question of categorical versus dimensional conceptualisation. It is argued that organising personality disorder into discrete subtypes generates high diagnostic covariation and within-diagnosis heterogeneity and that a dimensional model that considers personality disorder to exist along a continuum is preferable. This is true for BPD, where diagnosis by a categorical system is subject to particularly high heterogeneity (Hallquist Reference Hallquist and Pilkonis2012). It is argued that in psychiatry a categorical classification system does not define discrete disorder entities that are reliably delineated from other disorders (Hengartner Reference Hengartner and Lehmann2017). In this sense BPD ‘borders’ on a wide range of conditions and risks providing a catch-all diagnosis to explain a myriad of symptoms and problematic behaviours.

DSM-5 and ICD-10

DSM-5 defines the main features of BPD as a pervasive pattern of instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image and affect, in addition to marked impulsivity and self-injurious behaviour (Box 1) (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Although there is no stand-alone category of ‘borderline personality disorder’ in ICD-10 (World Health Organization 1992), ‘emotionally unstable personality disorder’, comprising the impulsive and borderline subtypes, is broadly equivalent.

BOX 1 Key symptom domains of borderline personality disorder

Emotional:

– Heightened emotional sensitivity

– Impaired emotional regulation

– Slow return to baseline from emotionally heightened state

– Chronic feelings of emptiness

– Difficulty controlling angry feelings

Interpersonal:

– Abandonment fears

– Relational instability

Behavioural:

– Impulsive behaviours (for example, reckless spending, binge eating, substance misuse)

– Self-harming

– Suicidal behaviours

Cognitive:

– Identity disturbance

– Transient psychotic symptoms

– Dissociative experiences

It was expected that the classification of personality disorders would undergo significant change during the revision process leading to DSM-5 to reflect the growing number of studies supporting a dimensional approach to diagnosis (Zachar Reference Zachar, Krueger and Kendler2016). To this end, a hybrid model of classification of personality disorder for DSM-5 containing categorical and dimensional elements was proposed. However, gaining consensus agreement proved elusive and the proposed model was rejected from the main body of DSM-5. The categorical personality disorder model represented in DSM-IV was retained in DSM-5 and the alternative hybrid model is printed in Section III (Emerging Measures and Models). In the alternative model, the essential criteria that define any personality disorder are both impairment in personality functioning and the presence of pathological personality traits. The hybrid methodology retains six personality disorder types: borderline personality disorder, obsessive–compulsive personality disorder, avoidant personality disorder, schizotypal personality disorder, antisocial personality disorder and narcissistic personality disorder.

ICD-11

In comparison, in ICD-11 (World Health Organization 2018) classification of personality disorders is dimensional and replaces categorical description. The focus is on the evaluation of a global impairment of personality functioning, classified according to degree of severity (personality difficulty, mild personality disorder, moderate personality disorder and severe personality disorder). The main determinants of severity include the degree of interpersonal dysfunction, the impact on social and occupational roles, cognitive and emotional experiences, and the risks of harm to self and others. In addition, the diagnosis may also be qualified with one or more prominent domain traits (negative affectivity, detachment, dissociality, disinhibition and anankastia). The trait qualifiers are available to describe the specific pattern of traits that contribute to the global personality dysfunction.

The initial proposal by the ICD-11 Personality Disorders Working Group (Tyrer Reference Tyrer, Crawford and Mulder2011) was met with concerns, particularly regarding the failure to include BPD in the classification and the consequent implications for research, therapy and access to treatment. It was intended that the characteristics associated with BPD could be found across the domains of negative affectivity, disinhibition and dissociality, rendering the need for the borderline label obsolete. However, this rationale was not accepted and, in response to these concerns, the option of applying a ‘borderline pattern descriptor’ was introduced (akin to the ICD-10 description of emotionally unstable personality disorder) but only after severity levels have been determined (Tyrer Reference Tyrer, Mulder and Kim2019). It is suggested that the classification of severity may inform prognosis and intensity of treatment, and trait qualifiers that reflect clinical features and dynamics of personality functioning may support the choice and nature of treatment (Bach Reference Bach and First2018). The ICD-11 classification may support rational clinical decision-making for people with BPD where treatment intensity is determined by illness severity (Irwin Reference Irwin and Malhi2019).

Epidemiology

Epidemiological studies in the USA report a lifetime prevalence of BPD of approximately 6% (Grant Reference Grant, Chou and Goldstein2008). In the UK, a large national sample showed a community prevalence of 0.7% (Coid Reference Coid, Yang and Tyrer2006). In primary care settings the prevalence of BPD ranges from around 4 to 6% (Moran Reference Moran, Jenkins and Tylee2000; Gross Reference Gross, Olfson and Gameroff2002). Despite this, BPD appears to be underrecognised by general practitioners (Moran Reference Moran, Rendu and Jenkins2001). Prevalence rates increase to 9.3% in community out-patient clinics and about 20% in in-patient settings (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Rothschild and Chelminski2005). Epidemiological studies have not found a gender difference in the prevalence of BPD; however, males are underrepresented in BPD research, owing to greater prevalence of women in clinical samples (Skodol Reference Skodol and Bender2003).

Aetiology: the biopsychosocial model

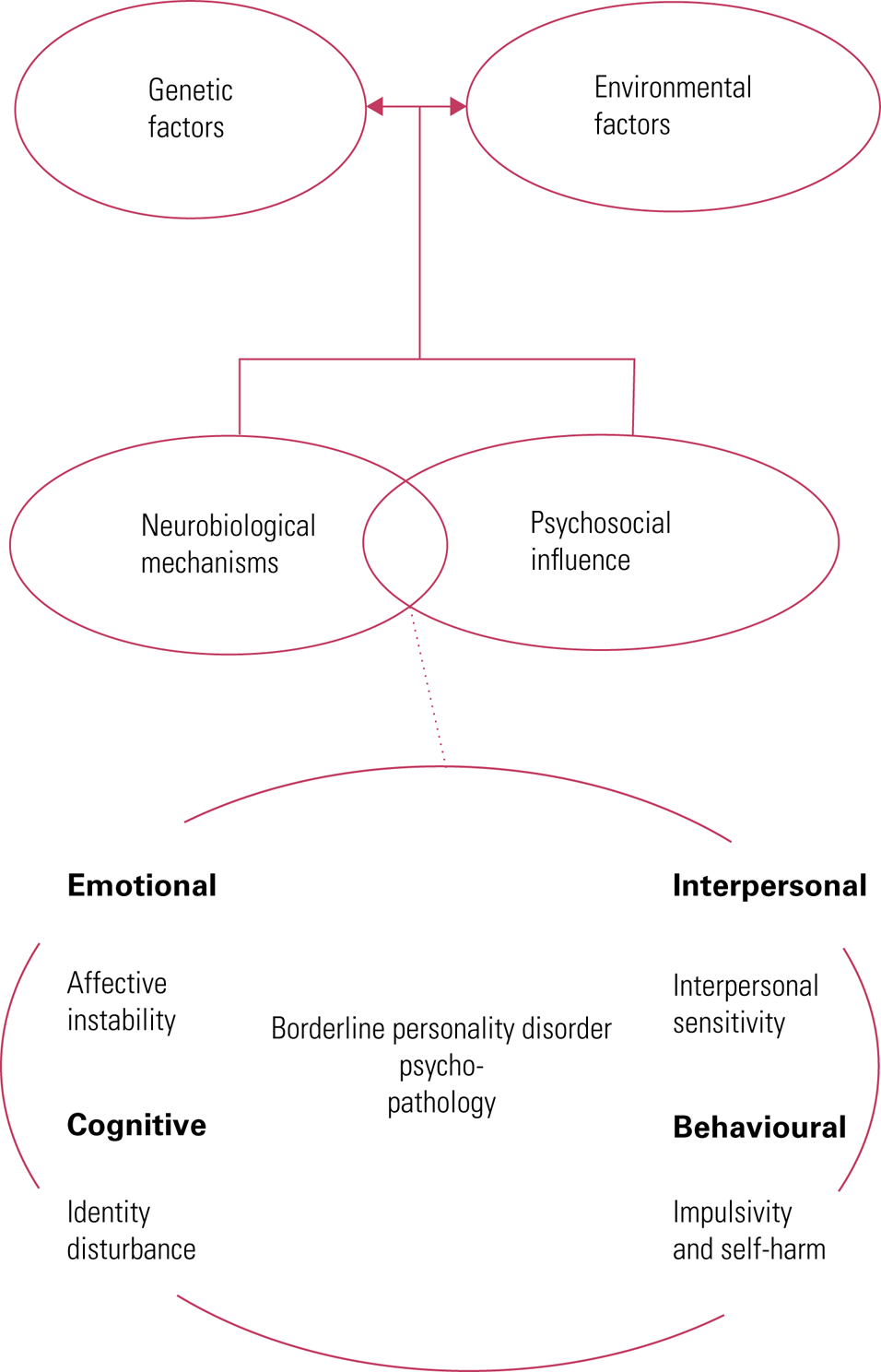

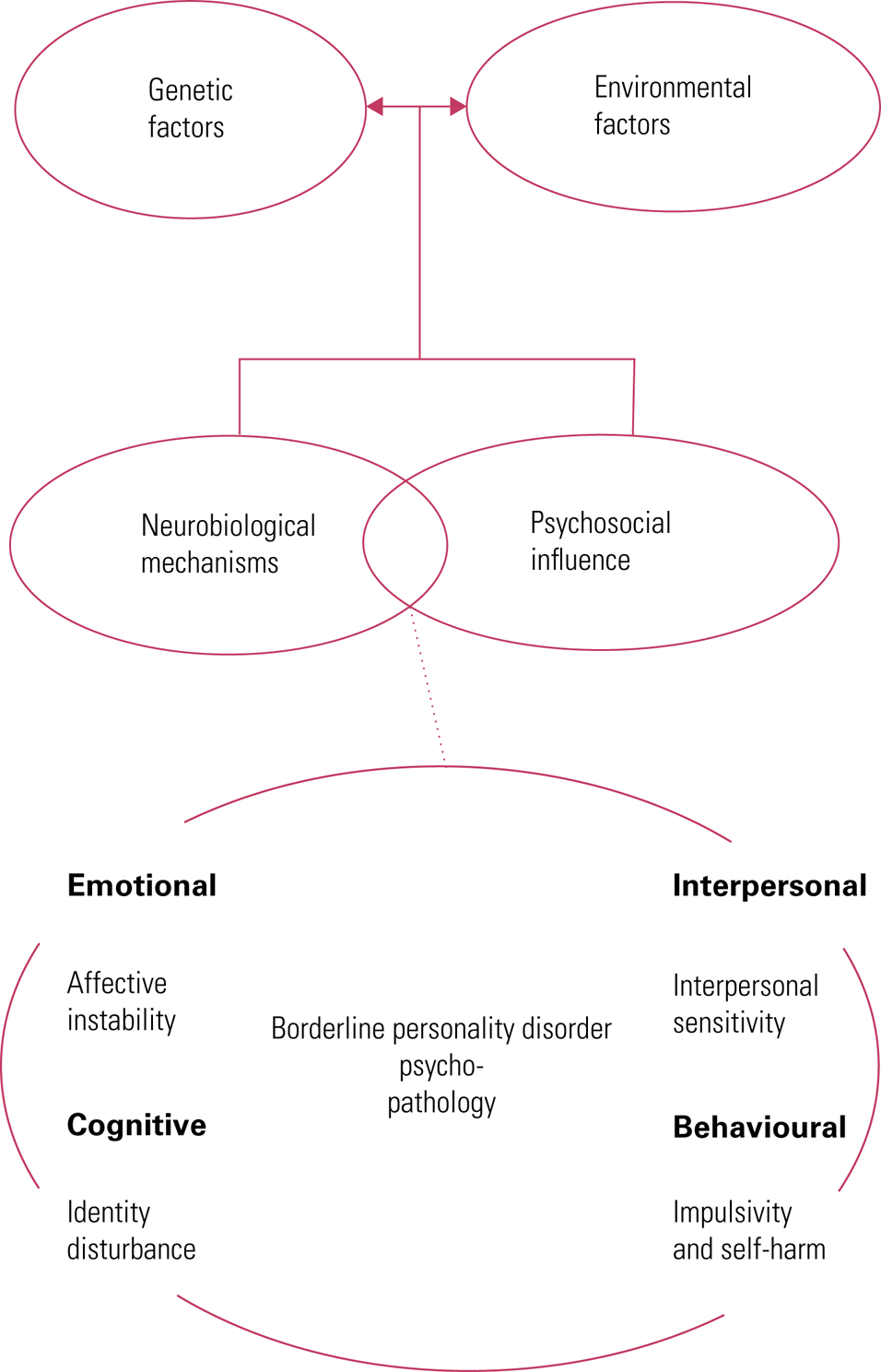

The pathways to development of BPD are complex and uncertain and it is likely that multifactorial contributions to aetiology include both genetic vulnerability and exposure to influences that undermine the development of social cognitive capacities and affect regulation (Fig. 1) (Amad Reference Amad, Ramoz and Thomas2014). Epigenetic processes such as DNA methylation, histone modifications and post-transcriptional regulation by non-coding RNAs may have a role in the pathogenesis of BPD as a consequence of childhood stress exposure (Martin-Blanco Reference Martin-Blanco, Ferrer and Soler2014a).

FIG 1 Aetiology of borderline personality disorder: the biopsychosocial model.

Biological factors

Genetic factors

Borderline personality disorder has been shown to be moderately heritable, with reported heritability estimates of 0.69 (Torgersen Reference Torgersen, Lygren and Oien2000). Contemporary literature (Sharp Reference Sharp and Kim2015) has highlighted the emergence of research that supports the complex biology–environment interactions that lend to the development of BPD over time.

Neurobiological mechanisms

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis

The HPA axis is one of the neuroendocrine systems that regulate the response of the body to stress. However, when activated by exposure to chronic stress, such as childhood trauma, the homeostatic functioning of the system can be compromised, leading to increased risk for developing stress-related psychiatric disorders. Findings suggest an association between dysfunction of the HPA axis and childhood trauma and the involvement of this system in the development of BPD (Cattane Reference Cattane, Rossi and Lanfredi2017).

Neurotransmitters and endogenous opioids

It has been suggested that neuropeptides involved in the regulation of affiliative and attachment behaviours, such as oxytocin, opioids and vasopressin, are altered in BPD and may represent neurobiological substrates of the interpersonal sensitivity dimension of the disorder (Stanley Reference Stanley and Siever2010). Studies also suggest that abnormalities in serotonergic function may underpin impulsive aggressive symptoms in BPD (Silva Reference Silva, Ituura and Solari2007).

Structural and functional brain changes

Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated evidence of both structural and functional deficits in brain regions concerned with regulation of affect, emotion recognition and attention, including the amygdala, orbitofrontal areas and the hippocampus. Structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies have reported reduced amygdala volume in people with BPD (Weniger Reference Weniger, Lange and Sachsse2009). It has been postulated that exposure to stress or early life experiences could lead to changes in hippocampal and amygdala size (Schmahl Reference Schmahl, Vermetten and Elzinga2003). Positron emission tomography (PET) studies also suggest frontolimbic dysfunction in people with BPD. Such abnormalities in brain regions involved in emotional control and processing may contribute to the affective instability of BPD (Koenigsberg Reference Koenigsberg, Fan and Ochsner2009).

Psychosocial factors

Developmental theories

Linehan (Reference Linehan1993) postulated a biosocial theory that BPD is a disorder of emotion regulation, heightened emotional sensitivity and reactivity and slow return to the emotional baseline that results from interactions between individuals with biological vulnerabilities and an emotionally invalidating environment. Children exposed to such a developmental context have difficulty understanding, representing and regulating emotional experiences.

Haigh (Reference Haigh2013) describes five necessary primary emotional development experiences for healthy personality formation: attachment, containment, communication, inclusion and agency. A secure early attachment gives the developing infant a coherent experience of existence and is the experience through which loss and change can be tolerated. Containment offered to the infant by parental figures through the establishment and enforcement of boundaries that can hold distress within agreed, safe limits forms the basis of a safe world in which intolerable feelings and experiences can be survived. A further principle of healthy personality development involves open communication, whereby the child's distress can be put into words and acknowledged and mirrored contingently by caregivers. Inclusion occurs when individuals are held in mind by others who share their environment and where interdependence and social cohesion can emerge. An environment that promotes empowerment and the exercising of agency supports individuation and self-efficacy. Disruption in these fundamental requirements for emotional well-being and healthy personality development can occur when abuse, neglect, deprivation or loss occur in the early environment.

Attachment theory

There is a strong association between insecure attachment style and BPD, which is in line with the understanding that relationship instability is a core feature of the disorder (Agrawal Reference Agrawal, Gunderson and Holmes2004). Bowlby postulated that human infants demonstrate behavioural patterns such as proximity-seeking, smiling and clinging, which evoke reciprocal care-taking behaviour in adult caregivers such as touching, holding and soothing. These reciprocal behaviours promote the development of an emotional tie between infant and caregiver that constitutes attachment. It is through this attachment relationship that the infant develops an internal representation of self and other (Bowlby Reference Bowlby1973). A secure attachment allows the child to explore their environment safe in the knowledge that the caregiver is available when needed. A secure attachment supports the development of a stable, consistent, coherent self-image and a sense that one is worthy of love, along with an expectation that attachment figures will generally be responsive and accepting. Hence, early-life interactions with attachment figures inform a cognitive template that influences the experience of adult relationships later in life (Madigan Reference Madigan, Hawkins and Plamondon2015). An insecure attachment relationship compromises the capacity to develop such mental representations of mental states of the self and the ability to reflect on and correctly interpret those of others. Insecure adult attachment is associated with borderline traits, whereas secure attachment has a negative predicative value for personality disorders (MacDonald Reference MacDonald, Berlow and Thomas2013). In BPD, attachment anxiety negatively affects social cognition, including the ability to mentalise and to differentiate self from other (Beeney Reference Beeney, Stepp and Haliquist2015).

Mentalising theory

Fonagy (Reference Fonagy and Bateman2008) proposes that deficits in mentalising capacity are a core aspect of the psychopathology of BPD. Mentalising is the capacity to make sense of ourselves and of others in terms of mental states. It is suggested that parental emotional under-involvement with children impairs the acquisition of normal social cognitive capacities and undermines a person's experience of their own mind. People with BPD tend to misread their own minds and the minds of others when in intense interpersonal encounters, particularly when emotionally aroused.

Adverse events

Borderline personality disorder is associated with childhood trauma more than any other personality disorder (Yen Reference Yen, Shea and Battle2002), which in turn is related to BPD symptom severity (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Hennen2006). Although a history of abuse is common in people with BPD, childhood sexual abuse is neither necessary nor sufficient for the development of BPD, and other childhood experiences, particularly neglect by caregivers, represent significant risk factors (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Williams and Lewis1997). Parental responsiveness following reports of abuse (believing the report, protecting the child and not expressing high levels of anger) may be a more important mediating factor than the pathogenic effects of the abuse itself in the long term (Horowitz Reference Horowitz, Widom and McLaughlin2001). It has also been postulated that the interaction of childhood trauma and temperamental traits, such as high neuroticism, particularly anxiety, could be associated with the severity of BPD (Martin-Blanco Reference Martin-Blanco, Ferrer and Soler2014b).

Prognosis

Prognosis of BPD should be considered optimistically in light of contemporary research evidence – several long-term outcome studies demonstrate high levels of remission. For example, 88% of people with BPD achieved remission over the course of a 10-year follow-up study (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Hennen2006). This study also identified a number of factors that were found to predict earlier time to remission, such as younger age, absence of childhood sexual abuse, no family history of substance use disorder and temperamental characteristics of low neuroticism and high agreeableness.

The assessment interview

If approached with interest and curiosity, the assessment process affords an opportunity to initiate the development of a therapeutic alliance with the patient. The clinician can maintain clear boundaries at the outset by explaining their role and the purpose and timeframe of the assessment. Adopting a warm and optimistic stance is important, particularly if the patient is anxious about the assessment and its potential outcome. The assessment may necessitate more than one session and should include a careful review of the available medical records to avoid premature arrival at an inaccurate diagnosis.

Screening tools

Personality assessment can be time-consuming so a brief screen for identification of people who might warrant further detailed assessment for personality disorder may be particularly valuable for the clinician. Self-report instruments are likely to overestimate prevalence rates of personality disorder (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman and Coryell1990) so a clinician-rated scale may be preferable (see ‘Assessment tools’ below).

Screening for personality disorder

The Standardised Assessment of Personality – Abbreviated Scale (SAPAS) is an eight-item screening interview for personality disorder in general rather than for specific personality disorders. It consists of eight questions, corresponding to a descriptive statement about the person. Possible scores range from 0 to 8. A score of 3 or more is sensitive and specific as a measure of the presence of a personality disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) (Moran Reference Moran, Leese and Lee2003).

Screening for BPD

The McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD) is a ten-item, true/false self-report screening measure for BPD (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Vujanovic and Parachini2003a). Each endorsed item is scored 1 point on a scale that ranges from 0 to 10. A cut-off score of 7 or more on the measure's ten items yields both good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of BPD as defined by DSM-IV.

Adapting the standard psychiatric assessment for BPD

Suspicion of personality disorder will arise during a standard psychiatric assessment when key features (Box 1) are elicited. When this is the case, it is important to be able to focus the history in order to distinguish BPD from other mental disorders with similar symptom profiles.

Presenting complaint

Symptoms should manifest in emotional (unstable mood, anger), cognitive/ideational (identity disturbance, dissociation, instability of goals), interpersonal (unstable and conflictual relationships, fears of abandonment) and behavioural domains (self-harm, impulsivity).

History of presenting complaint

Chronicity is the key feature here. One is looking for evidence of a disorder that began in adolescence or childhood and continued to manifest reasonably consistently throughout adulthood. The DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing BPD are the same in young people (under the age of 18 years) as in adults (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Although the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence acknowledges that BPD can occur in young people, it suggests that caution should be exercised when making a diagnosis of BPD in this age group owing to potential stigmatising effects of the diagnosis and limited evidence of its stability over time (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009). There is increasing awareness that personality problems can emerge later in life than late adolescence, even in middle to old age, when factors that may have previously compensated for personality disturbance are compromised (e.g. loss of a supportive relationship or occupational status).

Emotional domain

Emotional dysregulation is a core feature of BPD. It is characterised by heightened emotional sensitivity, impairments in regulation of emotional responses and slow return to baseline from emotionally heightened states. This feature may be elucidated by asking the patient whether their emotions are liable to change quickly over the course of hours or days. Emotions may shift rapidly, particularly in response to interpersonal interactions, but the person may not be able to readily identify reasons for vacillations in emotional states. It is helpful to enquire how the patient manages their emotions and whether they regret their actions when their emotions have been intense. It is likely that their behaviour and responses are determined by their mood and emotional states.

Chronic feelings of emptiness or hollowness may also be endorsed that may relate to a variety of factors. Emptiness in BPD is closely related to feeling hopeless, lonely and isolated. Avoidance of engaging with activities and relationships that have previously engendered distress and disappointment and shutting out of emotions may contribute to feelings of emptiness and lack of fulfilment.

Difficulty controlling angry feelings, characterised by low frustration tolerance and a pattern of discharging angry feelings in verbal or physical aggression, may be described. Anger is typically inappropriately intense, with rapid escalation in emotional intensity and a slow return to the baseline state.

Interpersonal domain

A seminal feature of BPD is relational instability. In the assessment interview this aspect of the disorder can be elucidated directly by asking the patient about the quality of past and current relationships with their lovers, parents or significant family members. A potentially useful rule of thumb is that the more intimate the relationship, the more likely symptomology will be demonstrated. However, this disturbance is on a continuum and for more disturbed patients this will manifest in relationships with decreasing intimacy, including those with work colleagues or even casual encounters. Open questions such as ‘What are you like in relationships?’ are a good way to start. After receiving general information one can then move on to more specific questions about experiences of self and others such as ‘In the relationship with [x] do you find your thoughts and feelings about him/her changing between extremes?’, ‘[In the relationship] do you experience your feelings and thoughts about yourself changing between extremes?’. Typical symptomology in BPD includes unstable mental representations of self and other, which at the extremes may rapidly switch between love and hate. The individual may be exquisitely sensitive within relationships and it is useful to ask ‘Are you concerned about what others think of you?’, ‘Do you find yourself sensitive and easily hurt, offended or disappointed by others?’ and ‘Do you worry about others intentions?’ to draw out this feature. A history may be revealed that includes a high number of intimate relationships over the years, characterised by easily falling in love, rapid development of intimacy, followed by disillusionment and estrangement. Similarly, relationships with parents, family members and friends may be conflictual and oscillate between extremes of idealisation and denigration.

A fear of being abandoned or rejected in relationships may be endorsed. Worries about perceived impending separation and loss may engender expressions or acts of suicide or self-harm in an effort to prevent abandonment. Ultimately, however, such behaviour may have a destructive effect on the very relationship the person is trying to protect. On the other hand, individuals may pre-emptively end relationships that they perceive will inevitably lead to abandonment, thereby avoiding the experience of being rejected.

Behavioural domain

Impulsive behaviours may arise for people with BPD in an understandable attempt to manage difficult emotional experiences. A history of impulsivity may be examined with the questions ‘Do you tend to seek out novelty or risky experiences?’ and ‘Do you make plans in advance and consider the possible consequences?’. If a history of impulsivity is endorsed, enquire which behaviours are problematic: ‘Have you had problems with eating binges, spending sprees, drinking too much and verbal outbursts?’. Other impulsive behaviours may include gambling, reckless driving and sexual activity that is later regretted. Self-harm and suicide risk assessment are detailed under ‘Risk’ below.

Cognitive domain

Identity

Another key feature is identity disturbance, which is characterised by the experience of uncertainty or instability about who one is. This may manifest in difficulty committing to goals and confusion about what one should do or believe: factors that impede the development of a coherent, stable sense of self-identity (Jorgensen Reference Jorgensen2010). Persons with BPD may endorse being easily influenced by other people and may not have clear distinctions between self and others. Questions such as ‘Do you have a sense of who you are and what makes you “you”?’ may be useful in examining this aspect of the diagnosis. A recent systematic review of sexuality-related issues in BPD highlights that individuals with BPD have higher rates of gender identity disturbance, which may be most appropriately considered to be part of general identity disturbance rather than a distinct comorbidity (Frías Reference Frías, Palma and Farriols2016).

Psychotic symptoms

According to DSM-5, people with BPD may experience transient stress-associated psychotic symptoms (American Psychiatric Association 2013). Contemporary studies demonstrate that people with BPD commonly report psychotic symptoms. In clinical populations chronic, persistent, critical auditory hallucinations are particularly common and are phenomenologically similar to those in schizophrenia (Pearse Reference Pearse, Dibben and Ziauddeen2014), and other symptoms, such as delusions, negative symptoms and formal thought disorder, may differentiate between the two groups (Tschoeke Reference Tschoeke, Steinert and Flammer2014). Emerging evidence suggests that hallucinatory experiences in BPD may be related to memories of trauma and can be intensified by life events and stress (Merrett Reference Merrett, Rossell and Castle2016).

Dissociation

Dissociative symptoms in BPD are positively associated with subjective experience of stress (Stiglmayr Reference Stiglmayr, Ebner-Priemer and Bretz2008). Dissociation has been defined as ‘disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control and behaviour’ (American Psychiatric Association 2013) and may manifest clinically as depersonalisation, derealisation or amnesia. It is a process that provides psychological containment and detachment from overwhelming experiences of a stressful nature. This feature may be elicited by enquiring whether the patient has ever felt detached or disconnected from their body, whether their body or the world around them has ever felt unreal, or whether they have no recollection for particular periods of time that cannot be explained by ordinary forgetfulness.

Family history

A family history of mood and impulse control disorders is associated with the development of BPD (White Reference White, Gunderson and Zanarini2003). The nature and quality of relationships with significant attachment figures should be explored, keeping in mind the importance of secure attachment in the facilitation of the development of a sense of the self being lovable and others as supportive and dependable (Bowlby Reference Bowlby1982).

Educational and occupational history

Psychosocial functioning includes both vocational and social functioning. Regarding social functioning, assess for the presence of at least one emotionally sustaining relationship in which the patient has regular, close contact without elements of abuse or neglect. Typically, educational and occupational function will be impaired. Features of BPD, particularly impulsivity and affective instability, prospectively predict negative academic achievement (Bagge Reference Bagge, Nickell and Stepp2004). In clinical populations, people with BPD experience greater impairment in work, social relationships and leisure compared with those with depression. Establishing a patient's educational attainments and occupational history may illuminate scholastic underachievement, incapacity to sustain employment or a poor disciplinary record.

Forensic history

A diagnosis of personality disorder is associated with an increased risk of violence compared with the general population. In BPD, externalised aggression can result in intimate partner violence and various types of aggressive criminal behaviour (Sansone Reference Sansone and Sansone2012). Offenders with personality disorder have 2–3 times higher odds of being repeat offenders than mentally or non-mentally disordered offenders (Yu Reference Yu, Geddes and Fazel2012), and enquiry about contact with the law should therefore form part of the standard personality disorder history.

Risk

Self-harm

The nature, variety and frequency of self-harming behaviours should be examined during the assessment interview. Community-based studies show rates of self-harm of 10% in young people; the behaviour is frequently repetitive and more common in females than males (Hawton Reference Hawton, Saunders and O'Connor2012). Self-harm takes a variety of forms, including cutting, bruising, burning, biting and head-banging. People with BPD who engage in self-harm report more frequent, severe and diverse methods of self-injury, have greater diagnostic comorbidity, and report more severe depressive symptoms, suicidal ideation and emotional dysregulation compared with those without a diagnosis of BPD who self-harm (Turner Reference Turner, Dixon-Gordon and Austin2015). Self-harm behaviours can be conceptualised as coping efforts that serve to moderate emotional distress.

Sexual risk

People with BPD and comorbid substance misuse report higher rates of sexual risk behaviours, sexually transmitted diseases and commercial sex-work (Harned Reference Harned, Pantalone and Ward-Ciesielski2011). Women with BPD are at increased risk of teenage and unwanted pregnancies compared with women with Axis I disorders (De Genna Reference De Genna, Feske and Larkby2012). Women with BPD are more likely to be raped by a stranger and be coerced to have sex than women without BPD traits (Sansone Reference Sansone, Chu and Wiederman2011).

Suicide

Enquiry about past episodes of attempted suicide is imperative. Suicide attempts are common in BPD, with 60–70% attempting suicide at some point and rates of completed suicide of 10% (Oldham Reference Oldham2006). A history of attempted suicide is a risk factor for completed suicide (Brent Reference Brent2011). Non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts are considered to be phenomenologically distinct, distinguished largely by motivational factors, for example a suicide attempt is motivated by a wish to die but self-harm may be motivated by an attempt to regulate emotion or communicate distress. Several characteristics are associated with suicide attempts in this population, including major depressive disorder (Soloff Reference Soloff, Fabio and Kelly2005), substance use disorders (Black Reference Black, Blum and Pfohl2004) and affective instability (Yen Reference Yen, Pagano and Shea2005). Feelings of deep hopelessness are associated with severe suicide-related behaviours. Hopelessness differentiates more severe suicide attempters from non-attempters (Stanley Reference Stanley, Gameroff and Michalsen2011).

Dependent children

During the assessment it is important to identify the needs of any dependent children, since parental mental health difficulties have an impact on parenting and, subsequently, mental health outcomes of the child (Vostanis Reference Vostanis, Graves and Meltzer2006). A recent systematic review explored the nature of parenting in mothers with BPD and the impact of such difficulties on child outcomes (Petfield Reference Petfield, Startup and Droscher2015). The findings describe an association between maternal BPD and reduced sensitivity and increased intrusiveness in their interactions with their infant children. Mothers with BPD also found it more difficult to structure their child's activities, and their family environments had higher levels of disorganisation and hostility and lower levels of cohesion. Mothers with BPD reported feeling less competent and satisfied in the parenting role and, in turn, children appeared to experience interactions with their mother as less satisfying. Children of mothers with BPD experienced a range of difficulties, including problems with labelling and understanding emotions, more difficulties with friendships, increased negative attributional style and self-criticism. Increased levels of depression, suicidality and behavioural problems were shown in children of mothers with BPD.

Assessment tools

Structured interviews

There are several diagnostic interviews available for the reliable and valid assessment of BPD (Carcone Reference Carcone, Tokarz and Ruocco2015). Formulating a reliable diagnosis of personality disorder can be challenging and formal personality assessment tools may be used as an adjunct to clinical interview.

The SCID-II (First Reference First, Spitzer and Gibbon1995) is a clinician-administered interview for the assessment of personality disorders according to DSM. The interview begins with an overview of the patient's patterns of behaviour and typical relationships. There is an optional screening questionnaire, which asks the patient to review items linked to each of the DSM-5 personality disorder criteria. The clinician then administers interview items that correspond to those endorsed on the screening questionnaire. Each item is scored as 1 (absent), 2 (subthreshold) or 3 (threshold). If a threshold is reached on a sufficient number of items, the category of personality disorder is deemed to be present.

The Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV) is a semi-structured interview consisting of 108 items pertaining to the past 2 years of the patient's life (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Sickel1996). It assesses the ten DSM-IV personality disorders, along with passive–aggressive and depressive personality disorders. Each disorder is rated on a scale of 0 (absent) to 2 (present): if the totalled score exceeds the threshold for a particular disorder the clinician can diagnose that disorder (Furnham Reference Furnham, Milner and Akhtar2014).

Specific measures of BPD

The Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD) is a clinician-administered rating scale that was designed to measure changes in borderline symptomatology overtime (Zanarini Reference Zanarini2003b). The scale features nine symptom items based on each of the DSM-IV criteria for BPD, grouped in four sectors reflecting the core areas of psychopathology: affective, cognitive, impulsive and interpersonal. Each symptom item is rated on a 5-point scale representing the frequency and severity of psychopathology. There are three affective symptoms in the ZAN-BPD: inappropriate anger/frequent angry acts, chronic feelings of emptiness, and mood instability. There are two cognitive symptoms: stress-related paranoia/dissociation and severe identity disturbance. The two impulsive symptoms include self-mutilative/suicidal efforts and at least two other forms of impulsivity. The interpersonal dimension includes intense, unstable relationships and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment. The four sector scores sum to provide a total score of borderline psychopathology.

Gender differences

Women with BPD have greater overall symptomology than men (Silberschmidt Reference Silberschmidt, Lee and Zanarini2015) and appear to exhibit an ‘internalising’ clinical picture manifested by higher rates of histrionic personality disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), other anxiety disorders, somatoform, affective and eating disorders (McCormick Reference McCormick, Blum and Hansel2007). Men tend to present with an ‘externalising’ picture, with higher rates of substance use disorders, antisocial personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder.

Comorbidity

Borderline personality disorder is a heterogeneous condition whose symptoms overlap with depressive, psychotic and bipolar disorders. It is important both to discriminate between BPD and disorders with shared symptoms and to recognise the presence of comorbidity when it does occur (although at times it is impossible to distinguish).

Affective disorders

Depression

Depression and BPD frequently co-occur and recurrence rates of depression are high in this population (Grilo Reference Grilo, Sanislow and Shea2005). A recent review (Yoshimatsu Reference Yoshimatsu and Palmer2014) examined the literature pertaining to major depressive disorder (MDD) in people with BPD. It is helpful to keep in mind that depression in BPD is experienced as subjectively more severe, is more related to interpersonal sensitivity, is more persistent than depression without BPD and tends not to improve until BPD improves. A 10-year study revealed that BPD and MDD have reciprocal negative effects on one another's time to remission and time to relapse (Gunderson Reference Gunderson, Stout and Shea2014).

Bipolar affective disorder

Phenomenological similarities between BPD and bipolar affective disorder confer a clinical challenge when distinguishing between these disorders and recognising their co-occurrence. This is important for a variety of reasons, including treatment, prognosis and suicide risk. Bipolar disorder with comorbid BPD has a more severe presentation of illness than bipolar disorder alone and BPD is highly predictive of a future diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Bipolar affective disorder and BPD are both associated with increased rates of suicide attempts, but their co-occurrence confers an additive risk, with the influence of BPD greater than that of bipolar affective disorder (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman, Martinez and Young2014). Clinical studies suggest that people with BPD may be at increased risk of being misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder (Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman and Morgan2013). Diagnosis relies on endorsement of similar symptoms, which may result in diagnostic error, for example in distinguishing between the emotional instability consistent with BPD and the affective disturbance of bipolar disorder. However, the pattern of affective instability in BPD is characterised by transient changes in mood in response to interpersonal stressors, whereas bipolar disorder is associated with more sustained mood shifts (Paris Reference Paris and Black2015). Additionally, mood change in BPD is usually from euthymia to anger, which contrasts with the shift from depression to elation seen in bipolar disorder (Koenigsberg Reference Koenigsberg2010).

Anxiety disorders

Borderline personality disorder is strongly associated with anxiety disorders, with elevated rates of panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, simple phobia, obsessive–compulsive disorder and PTSD (Grant Reference Grant, Chou and Goldstein2008). Attention should therefore be paid to examining for the presence of such comorbid disorders during the assessment.

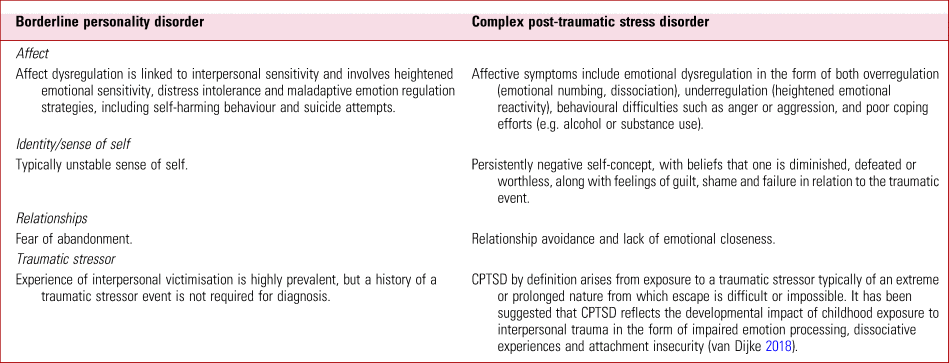

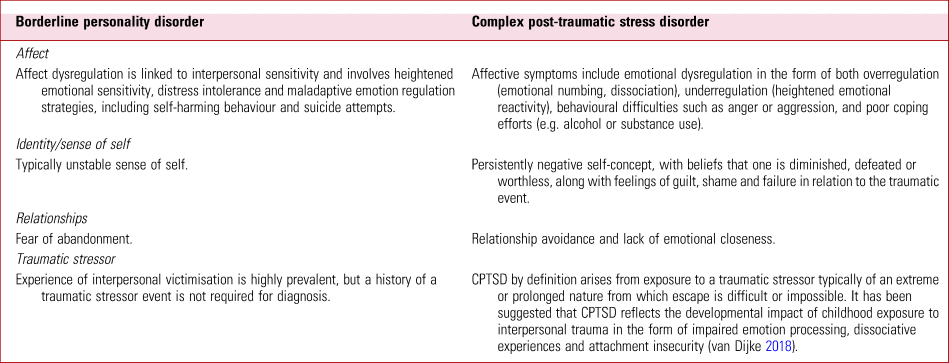

BPD with PTSD versus complex PTSD

Childhood trauma exposure increases the risk for development of a range of psychiatric diagnoses, including personality disorders, and there has been much debate on whether complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is distinguishable from BPD and comorbid PTSD or whether it is an amalgam of these disorders. ICD-11 has introduced an additional CPTSD construct comprising the three core features of PTSD (re-experiencing of the traumatic event(s) in the present, internal or external avoidance of traumatic reminders and hypervigilance to a sense of current threat) and additional disturbances in emotional dysregulation, self-concept and interpersonal relationships (World Health Organization 2018). CPTSD has been proposed as an alternative way to conceptualise the symptoms of adults exposed to prolonged and severe interpersonal trauma. Distinguishing between BPD and CPTSD – disorders that share characteristics in the domains of affect, identity and relational functioning – may present a diagnostic challenge, particularly since it is known that BPD is a disorder associated with traumatic experiences.

However, clinical differences are recognisable and will inform differences in treatment approach (Maercker Reference Maercker, Brewin and Bryant2013). Symptoms that are highly indicative of BPD rather than CPTSD include frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment, unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterised by alternating between extremes of idealisation and devaluation, markedly and persistently unstable self-image or sense of self, impulsiveness and the presence of suicidal and self-injurious behaviour (Cloitre Reference Cloitre, Garvert and Weiss2014). Further details of these and other distinguishing symptoms are outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1 Some features in the differential diagnosis of borderline personality disorder and complex post-traumatic stress disorder

It has been suggested that CPTSD reflects the developmental impact of childhood exposure to interpersonal trauma in the form of impaired emotion processing, dissociative experiences and attachment insecurity (van Dijke Reference van Dijke, Hopman and Ford2018). Although the overlapping features of CPTSD and BPD may reflect conceptual similarities between these conditions, it has been argued that CPTSD is neither a replacement diagnosis for BPD nor a subtype of BPD itself. Rather, it has been suggested that CPTSD captures the developmental effects of exposure to complex trauma and may better describe the group of people with a history of prolonged and severe trauma (such as childhood sexual abuse, torture or slavery) who develop fear-based symptoms related to traumatic stimuli (core PTSD symptoms) and trauma-related disturbances that are enduring and pervasive (emotion dysregulation along with altered relational and self-schemas) who have been previously ascribed a BPD diagnosis (Ford Reference Ford and Courtois2014).

Substance use

The lifetime prevalence of substance use disorder in people with BPD is 78% (Tomko Reference Tomko, Trull and Wood2013). Persons with BPD and a substance use disorder are more impulsive and less clinically stable than those with BPD without substance misuse (Kienast Reference Kienast, Stoffers and Bermpohl2014), making identification and management of substance misuse a priority.

Schizophrenia

Borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia frequently co-occur and BPD has a negative effect on the longitudinal course and outcome of people with schizophrenia (Bahorik Reference Bahorik and Eack2010). People with schizophrenia and comorbid BPD report more childhood trauma than people with schizophrenia without BPD (Kingdon Reference Kingdon, Ashcroft and Bhandari2010). As previously stated, psychotic symptoms frequently occur in BPD and careful exploration of other symptoms, including delusional beliefs, negative symptoms and formal thought disorder, may help to discriminate between BPD and primary psychotic illness.

Eating disorders

A study examining the prevalence of eating disorders in a large sample of people with personality disorder found rates of 17% in women and 3% in men (Reas Reference Reas, Ro and Karterud2013). A significantly higher proportion of women with BPD were diagnosed with bulimia nervosa or eating disorder not otherwise specified, whereas the rate of anorexia nervosa was significantly elevated in women with obsessive–compulsive personality disorder. Bulimia nervosa is associated with impulsivity and emotion dysregulation, whereas anorexia nervosa is associated with obsessive–compulsiveness, rigidity and perfectionism.

Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

In clinical populations the overlap between bipolar disorder, BPD and ADHD is high (Eich Reference Eich, Gamma and Malti2014). BPD and ADHD share features of impulsivity and difficulty controlling anger and aggression. When ADHD co-occurs with BPD impulsivity may be further increased. It may be helpful to remember that the characteristics of impulsivity in ADHD are different from those in BPD. In ADHD, individuals report stronger tendencies to act without thinking, more problems with planning and more difficulties maintaining attention on a task (Ende Reference Ende, Cackowski and Van Eijk2016).

Dissociative disorders

Chronic, complex dissociative symptoms and disorders are common in BPD, and cluster B personality disorders in particular are associated with non-epileptic seizures (Beghi Reference Beghi, Negrini and Perin2015).

Physical assessment

Mental disorder is associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, social disadvantage, difficulties accessing medical healthcare and unwanted physical effects of psychotropic medication, and people with personality disorders in particular struggle to obtain adequate healthcare and have greater unmet treatment needs (Hayward Reference Hayward, Slade and Moran2006). A body of evidence is emerging that asserts that people at risk for personality disorders in the general population are at significantly increased risk for poor physical health. Therefore, careful screening and treatment of physical health conditions among people with BPD is warranted.

Recognising and using the countertransference

Working with patients with BPD can evoke strong feelings in the clinician and it is of diagnostic utility to attend to these emotions while working with the patient, i.e. recognising countertransference. The patient may interact with the clinician in ways that reflect repetitive patterns of relating to significant others (Colli Reference Colli, Tunzilli and Dimaggio2014), yielding clues as to how they interact within their relationships. In personality disorder, countertransference responses occur in predictable patterns, which are useful in understanding the patient's patterns of relating to others (Betan Reference Betan, Heim and Zittel Conklin2005). Patients with BPD tend to arouse more negative responses, with clinicians reporting feeling inadequate, anxious and apprehensive about failing to help the patient and guilt when their patient is in distress. Immature defence mechanisms such as splitting and projective identification are strongly associated with borderline psychopathology (Zanarini Reference Zanarini, Frankenburg and Fitzmaurice2013). Splitting is a primitive defence mechanism in which there is a failure to integrate the positive and negative aspects of the self and others into a cohesive whole. Other people may be compartmentalised into ‘all good’ or ‘all bad’ groups and the patient may hold alternating contradictory representations of themselves. Projective identification involves an unconscious disavowal of aspects of oneself while simultaneously attributing these disavowed aspects to another. In the clinical encounter, such disavowed attributes from the patient can be induced in the clinician so that the clinician as a recipient of the projection identifies with the emotions induced in them, which can lead to a belief that the projected attributes originate from the clinician rather than the patient (Schlapobersky Reference Schlapobersky2016). Therefore, it may be clinically helpful to reflect on one's countertransference experience as part of the assessment process as a source of information about the patient.

Giving a diagnosis

Clinicians may be concerned that disclosure of the diagnosis of BPD may engender pessimism in the patient and may not wish to ascribe a diagnostic ‘label’ that may be perceived as pejorative (Lequesne Reference Lequesne and Hersh2004). However, not sharing the diagnosis of BPD disadvantages patients by denying the potential relief that a diagnosis unifying their various symptoms may bring and limiting the therapeutic options available to them if the presence of a diagnosis is a treatment requirement. It is important to explain the diagnosis of BPD in a clear, understandable manner, all the while maintaining a sense of hopefulness for change and recovery. Therefore, sharing a diagnosis of BPD is an opportunity for psychoeducation about both the diagnosis and treatment options, which can help the patient to make informed decisions about their care (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2009). It facilitates the development of a shared understanding of the patient's difficulties and a common language to discuss symptoms. It can be helpful to use examples from the person's experience to illustrate features of the diagnosis, with a view to making the diagnosis personally relevant and meaningful. The patient should be afforded the opportunity to ask questions and to seek clarification on what has been discussed. Helpful online resources for patients and significant others are available from the Royal College of Psychiatrists and reputable mental health websites such as MIND.

Conclusions

Borderline personality disorder is a common, serious and clinically heterogeneous disorder, although the prognosis should be considered optimistically. Particular attention should be paid to assessing for psychiatric comorbidity, as BPD is highly comorbid with other mental disorders and its presence typically confers a worse prognosis. Careful clinical assessment should promote understanding of the patient's emotional, behavioural, relational and occupational needs, in addition to informing assessment of risk and physical health status among people with this disorder.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 The prevalence of BPD in primary care is estimated to be about:

a 0.5%

b 15%

c 5%

d 10%

e 20%.

2 Regarding the prognosis of BPD, the following factor predicts earlier time to remission:

a older age

b history of childhood sexual abuse

c family history of substance misuse

d high neuroticism

e high agreeableness.

3 Research evidence regarding BPD shows that:

a BPD is not associated with increased risk of sexually transmitted diseases

b impulsivity and affective instability prospectively predict negative academic achievement

c children of mothers with BPD experience similar levels of satisfaction in interactions with their mothers as children of mothers without BPD

d people with BPD are not at increased risk of death by natural causes

e rates of completed suicide in BPD are around 1%.

4 Special tests useful in the diagnostic assessment of BPD include:

a PANSS

b S-RAMM

c SCID-II

d GDS

e HCR-20.

5 Regarding gender differences in BPD:

a BPD is more prevalent in women than in men

b self-harm is more frequent in women with BPD than in men with BPD

c women typically present with an ‘externalising’ clinical picture

d anorexia nervosa is the most commonly associated eating disorder in women with BPD

e substance misuse is less common in men with BPD.

MCQ answers

1 c 2 e 3 b 4 c 5 b

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.