Introduction

António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations opened the twenty seventh Conference of Parties (COP27) by telling participants that:

“Greenhouse gas emissions keep growing. Global temperatures keep rising. And our planet is fast approaching tipping points that will make climate chaos irreversible. We are on a highway to climate hell with our foot on the accelerator.”

Indeed, there has been an increasingly urgent tone in policy discussions regarding climate change, and as a result it is perhaps unsurprising that scholarship in this field has rapidly grown over the course of the last decade. Given this, there is increased understanding about the social impact of climate change (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (henceforth IPCC), 2014; IPCC, 2022) with a growing focus on how people who are socially, economically, politically and institutionally vulnerable will be affected the most (IPCC, 2014: 6). Furthermore, evidence suggests that the impact of climate change will be substantial and far-reaching, impacting diverse areas such as agriculture, labour productivity, economic growth, civil conflict, and migration (IPCC, 2022) to name just a few. As such, there is significant attention being paid to developing and implementing new policies that seek to provide measures of climate change adaptation, and mitigation policies that reduce the harmful greenhouse gas emissions that are causing itFootnote 1 .

Whilst a broad literature base grounded in both theoretical and empirical work relating to climate change and climate policy exists, research and scholarship within the discipline of social policy is often very specific, complex, and over-specialised (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014). Indeed, as a result of this Williams (Reference Williams2021) has argued there is an urgent need to start comprehensively embedding environmental thinking across all domains of social policy. Given this, whilst acknowledging the importance of existing work conducted within the field of social policy and the environment, and indeed published in a previous Themed Section of this journal (see Beveridge Report Collection: Towards A Sustainable Welfare State, Coote, 2022), this paper takes a different, and in many respects, broader perspective. This paper responds to Williams’ call, considering the current challenges for social policy as a discipline within the context of the climate crisis, and suggesting pathways to embed thinking about climate change. Our approach here is deliberately broad as it is our ambition to highlight the relevance of the climate crisis to all areas of social policy as it currently stands and to provide practical ways in which this can be achieved.

The paper begins by outlining existing work that draws together social policy, the environment, and climate change. It then presents findings from workshops held with social policy scholars, policymakers, and practitioners, using these discussions to propose pathways to embed climate change within the field of social policy, such that thinking and doing on climate change and the environment is no longer a niche activity for the discipline.

Background: what do we know about social policy and the environment?

Overview

As Williams (Reference Williams2021:3) argues scholars of social policy and the environment have been ‘pushing hard to get onto the social policy agenda over the past two decades’. This has occurred with varying degrees of success, with many discussions about the environment and social policy occurring at the edges of the discipline rather than at its core. Moreover, it has perhaps resulted in a vast literature that is highly relevant to social policy that is fragmented across multiple disciplines including geography, politics, and sociology (e.g. Bell, Reference Bell2014 and Gillard et al., Reference Gillard, Snell and Bevan2017).

There has been a number of explicit attempts to make connections between social policy and environmental issues - led by a number of trailblazers such as Fitzpatrick (Reference Fitzpatrick, Ellison and Pierson2003), Gough (Reference Gough, Kaasch and Stubbs2014a, Reference Gough and Kennett2014b, Reference Gough2017), Gough et al. (Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008), Cahill (Reference Cahill2002) and Huby (Reference Huby1998), and more recently Koch and Mont (Reference Koch and Mont2016), Hirvilammi and Koch (Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020), Büchs and Koch (Reference Büchs and Koch2017), Mandelli (Reference Mandelli2022), Snell and Haq (Reference Snell and Haq2014) and Snell et al. (Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022). Literature that exists within the discipline tends to focus on a number of core issues: the societal impact of environmental problems; resulting challenges posed for social policy and welfare systems; and an imagining of what a future, sustainable, social policy might look like and the policy instruments necessary to deliver this. Throughout this literature is a concern about the unsustainability of existing systems, institutions, and policies.

Whilst we acknowledge the broader (and indeed larger) literature base that operates beyond the discipline, and indeed it is our intention in this paper to promote interdisciplinary working, it is the specific literature that focuses on how environmental challenges intersect with social policy that we focus on here, aiming to summarise existing knowledge within the field and to highlight gaps in knowledge.

Inequalities, the environment, and social policy

At its heart the social policy literature emphasises that environmental issues, and climate change in particular present a challenge to everyday life, and that intersecting inequalities exacerbate these challenges. Cahill (Reference Cahill2002), Huby (Reference Huby1998), Gough (Reference Gough2017), and Gough et al. (Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008) have led the way here – for example, highlighting the relationship between poverty and environmental hazards; where the poorest in society will suffer disproportionately from, and are most vulnerable to, environmental hazards. This work emphasised the synergy between environmental issues and social policy, making the argument that not only is there a synergy, but poverty and environmental degradation are explicitly seen to perpetuate each other (Huby, Reference Huby1998: 156), for example, climate change is regarded by Gough as a ‘threat multiplier’ (Gough, Reference Gough2017: 37; Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008). Therefore, the imperative to solve social problems surrounding poverty becomes all the more pressing as the negative effects of climate change are felt more keenly. Fitzpatrick (Reference Fitzpatrick2014)’s concept of ‘eco-social poverty’ enhances the view that we cannot address climate change without simultaneously resolving social problems given the inherent connections between the two. Whilst this literature considers existing patterns of inequality at a range of administrative/spatial levels, it is also closely tied to sustainable development policy narratives that raise concerns about future generations (i.e. intergenerational equity) (Gough, Reference Gough2017; Cahill, Reference Cahill2002; Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008).

Existing challenges to policy and policymakers are also discussed within this context, for example, scholarship within the field discusses the need to both balance and integrate environmental and social policies to ensure that the former do not prevent people’s immediate needs being addressed through policy, and vice versa (Cahill, Reference Cahill2002; Huby, Reference Huby1998; Snell and Thomson, Reference Snell, Thomson, Ramia and Farnsworth2013; Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011; Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008). Most recently, Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022 highlighted the importance of making eco-social policies that provide ‘protection’ against the risks of the ‘green challenge’ (e.g. support to protect low income households from rising energy costs associated with changes in energy policy), ‘investment’ to ensure that those affected by policy changes can participate in them (e.g. through active labour market policies to support the creation of green jobs and associated training), and that play a ‘preventative’ function in reducing the environmental impact of social policies (e.g. through investment in low carbon social housing or green pension fund investment).

This body of work has gathered both momentum and gained nuance. The concept of ‘sustainable welfare’ (see below) has gained significant traction, there has been a greater emphasis in most recent work of the significance of the (just) transition to a low carbon economy/net zero (Gough, Reference Gough2022; Krause et al., Reference Krause, Stevis, Hujo and Morena2022; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022), and the integration of climate and environmental justice concepts with social policy literature has reframed and refreshed debates around social policy, inequality, and the environment (Bell, Reference Bell2014; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022; Snell, Reference Snell, Yeates and Holden2022; Urban and Nordensvärd, Reference Urban and Nordensvärd2013; Nordensvärd, Reference Nordensvärd2017; Williams, Reference Williams2021, see also Middlemiss et al. and Thomson et al. within this themed section).

Concerns are also raised over the threat that environmental problems pose to current systems and policy responses – for example, social welfare systems (see, for example, Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008; Dean, Reference Dean2019); although this literature is relatively limited within the discipline (even if more present in other fields – see, for example, British Medical Association, 2023; Paterson et al., Reference Paterson, Berry, Ebi and Varangu2014).

Sustainable Welfare and related concepts

The most coherent body of literature within the field at present falls under the banner of ‘sustainable welfare’, with two special issues published on the topic between 2020-2022.

Literature within this sphere is often highly critical of existing systems, structures and responses. Concepts such as ‘eco social welfare’ ‘sustainable welfare’ ‘eco social state’ ‘eco social policy’ and ‘sustainable wellbeing’ originally inspired by the work of Fitzpatrick, Gough, Cahill, and Koch have been developed as part of this critique, stemming from ‘green criticisms’ of the welfare state first made in the 1970s (Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020). Whilst the concepts take different approaches, Hirvilammi and Koch (Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020: np) use the umbrella term of ‘sustainable welfare’ to collectively describe these, arguing that they share a ‘common ambition to develop welfare concepts and policies that consider the environmental crisis and/or limits to growth’ (Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020: np).

Many writing from this perspective highlight the problematic relationship between welfare states and their systems on growth, arguing instead in favour of welfare systems that operate within planetary boundaries (Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2017) and are growth-critical in outlook. Indeed, in almost all literature within this field, the current political economy of neoliberalism (Gough, Reference Gough2017:14; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014: 13) and consumerism (Cahill, Reference Cahill1994: 180; Gough, Reference Gough2017: 170) are challenged. For example, after blaming the existence of eco-social poverty on unequal access to economic growth, Fitzpatrick suggests a possible solution that calls for new forms of economic organisation that are more socially egalitarian and inclusive (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014: 214). Fitzpatrick is not alone in suggesting that sustainability is incompatible in the current global political economy of growth (see Koch, Reference Koch2022 and Coote, 2022). In the wider literature that takes a global perspective, environmental problems are often viewed as a result of globalisation’s drive for economic growth, expansion of global capitalism and unbridled consumerism (Assadourian, Reference Assadourian, Nicholson and Wapner2015; George and Wilding, Reference George and Wilding2002: 53; Jackson, Reference Jackson2017; Laurent, Reference Laurent, Vanhercke, Spasova and Fronteddu2020). Given the context of globalisation and the global nature of climate change, the need for a global outlook is highlighted here, particularly as the global political economy of capitalism is viewed as a facilitator of environmental harm (White, Reference White2014: 161) and that global economic priorities ‘swamp’ environmental goals (Yearley, Reference Yearley and Ritzer2007: 245). This literature contends that the constant capitalist aim of growth holds significant costs on society and the environment (Midgley, Reference Midgley, Midgley, Surender and Alfers2019: 24; Sklair, Reference Sklair2001: 206).

Given that scholarship within the sustainable welfare tradition tends to raise critical questions about how current economic models and welfare systems currently function and how they could function in a greener future (Gough, Reference Gough2017; Cahill, Reference Cahill1994; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick, Ellison and Pierson2003, Reference Fitzpatrick2014; Ferrera and Rhodes, Reference Ferrera and Rhodes2000; Koch and Mont, Reference Koch and Mont2016; Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020; Zimmerman and Graziano, Reference Zimmermann and Graziano2020; Bohnenberger, Reference Bohnenberger2020; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020; Büchs and Koch, Reference Büchs and Koch2017; Gough, Reference Gough2015; Büchs, Reference Büchs2021, Laurent, Reference Laurent, Vanhercke, Spasova and Fronteddu2020) it is not surprising to see calls for an upheaval of social policies (and the systems they operate within) economic systems in favour of new, ‘eco-social’ policies (Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014; Fitzpatrick and Cahill, Reference Fitzpatrick and Cahill2002; Gough, Reference Gough2017, Reference Gough2022; Coote, 2022, Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022). For example, Büchs (Reference Büchs2021) calls for universal basic services, while Gough (Reference Gough, Kaasch and Stubbs2014a) puts forward proposals for personal carbon rationing and trading.

Most recently research in this field has taken steps to address the criticism that eco-social policy scholarship is of a ‘predominantly normative orientation’ and has responded to the call for more ‘empirically grounded approaches’ (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022: 334). Mandelli (Reference Mandelli2022), for example, provides a much needed definition of eco-social policy and an associated typology to help understand and categorise its different actual and potential functions. Moreover, the work of Bohnenberger (Reference Bohnenberger2020) attempts to move the ‘sustainable welfare’ debate into a more applied social policy setting, outlining a new typology for welfare benefits within an environmentally aware context. Similarly, the work of Khan et al. (Reference Khan, Hildingsson and Garting2020) considers the integration of environmental concerns into urban policy, and Brandl and Zielinska (Reference Brandl and Zielinska2020) consider the relationship between sustainable welfare, degrowth, and quality of work.

Building on existing literature and identifying gaps in knowledge

Despite the advances described above, especially in terms of the sustainable welfare and eco social policy fields, there remain gaps in knowledge, with the environment still regarded as a peripheral issue in most social policy debates.

Significantly, there is virtually no recent social policy scholarship on the impact of climate change and climate policy on existing social and physical infrastructure, institutions, and processes, and (with the exception of Snell et al., Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022; Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011; Urban and Nordensvärd, Reference Urban and Nordensvärd2013; Nordensvard, Reference Nordensvärd2017) limited applied work on the broader implications of the ‘transition to net zero’ for both societies and social policies. Moreover, the burgeoning ‘sustainable welfare’ literature has historically lacked application (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022), and where it has been applied this is often limited to a limited number of policy areas – for example, housing, energy, or labour markets. This highlights another gap, that the original, literature base (for example, the work of Cahill and Huby) that drew together issues of the environment and social policy in broad terms is now very dated and has not been replicated, and this has perhaps created a ‘patchiness’ where the significance of the environmental challenges across all aspects of the discipline has been lost.

As such, there is much work still to be done, and rapidly given the increasingly urgent tone within international, national, and local policy debates (for example, 260 local authorities in the UK have declared a climate emergency, and terms such as ‘climate crisis’ and ‘climate chaos’ are increasingly common). Given these gaps there is a clear need for scholarship that:

-

Creates an up to date, comprehensive understanding as to how climate change is inherently interconnected with social policy;

-

Identifies the most significant established and emerging issues and pressing gaps in knowledge;

-

Considers how the discipline can begin to embed these issues together

-

Provides practical pathways that enable the integration of social and environmental policies (see, for example, Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022).

The paper represents a significant contribution to knowledge within the field as it seeks to broaden discussions about social policy and climate change; to identify theoretical and empirical relationships that exist between the two fields but have not been fully recognised in existing scholarship; and to bring new perspectives and voices into the discussion.

Methodology

Our data is drawn from two participatory onlineFootnote 2 workshops held via Zoom with 106 social policy scholars, policymakers, and practitioners over the course of November – December 2021. Our participants were recruited using a call circulated to key disciplinary mailing lists, as well as targeted emails to Heads of Departments, resulting in a diverse group from a range of institutions, including Russell Group, post 1992, and overseas universities, alongside practitioners from various third sector organisations. Informed consent was gained at the point of signing up for the workshops, with participants made aware that they could opt-out at any point. While there are some limitations to our sampling approach, namely that it was self-selecting, our workshops represent the first large-scale attempt to draw together the social policy community into such discussions, including areas of the discipline that have rarely, if at all, considered climate change.

Participants were asked to sign up to one of eleven thematic breakout groups with the themes drawn from an adapted version of the Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) Subject Benchmark Statement for Social Policy (2019) and covering the themes indicated in Box 1.

Box 1. Thematic breakout groups

Crime and Criminal Justice;

Education;

Family and Childhood;

Food poverty;

Fuel poverty;

Health and Social Care;

Housing and Urban Regeneration;

Income Maintenance and Social Security;

Migration;

Water Poverty;

Work, Employment, and Labour Markets

Source: Adaptation of Quality Assurance Agency for UK Higher Education (2019)

Two page rapid reviews of existing literature on climate change and the themes were provided to workshop participants in advance of the sessions, to give participants an overview of research to date, and to trigger group discussions. Over the course of the two, one and a half hour long sessions, the breakout groups mapped the relationships between the themes and climate change, loosely anchored around the ‘Johari Window’ framework (Luft and Ingham, Reference Luft and Ingham1955; see Figure 2 for an example). This is used throughout social science research, often because, as Justo (Reference Justo2019) highlights it allows critical engagement with knowledge: allowing consideration of what we know, what we think we know, our biases and unconscious decisions, and assumptions. Other materials including ‘jamboards’ (an online equivalent of adding post-its to a board – see Figure 1 for an example) were used to generate discussion and record key points. The online workshops switched between breakout rooms and plenary sessions to allow in depth discussions in the smaller, thematic groups, alongside whole group discussions that allowed a broader discussion about common themes, and key priorities for the discipline to be held. Notes of the discussions were taken by members of the team. A qualitative thematic analysis of the outputs from each discussion was undertaken (notes, jamboards, the completed Johari Window), highlighting the main themes within each group (presented in Finding section), and then across the discussions (presented in Discussions section).

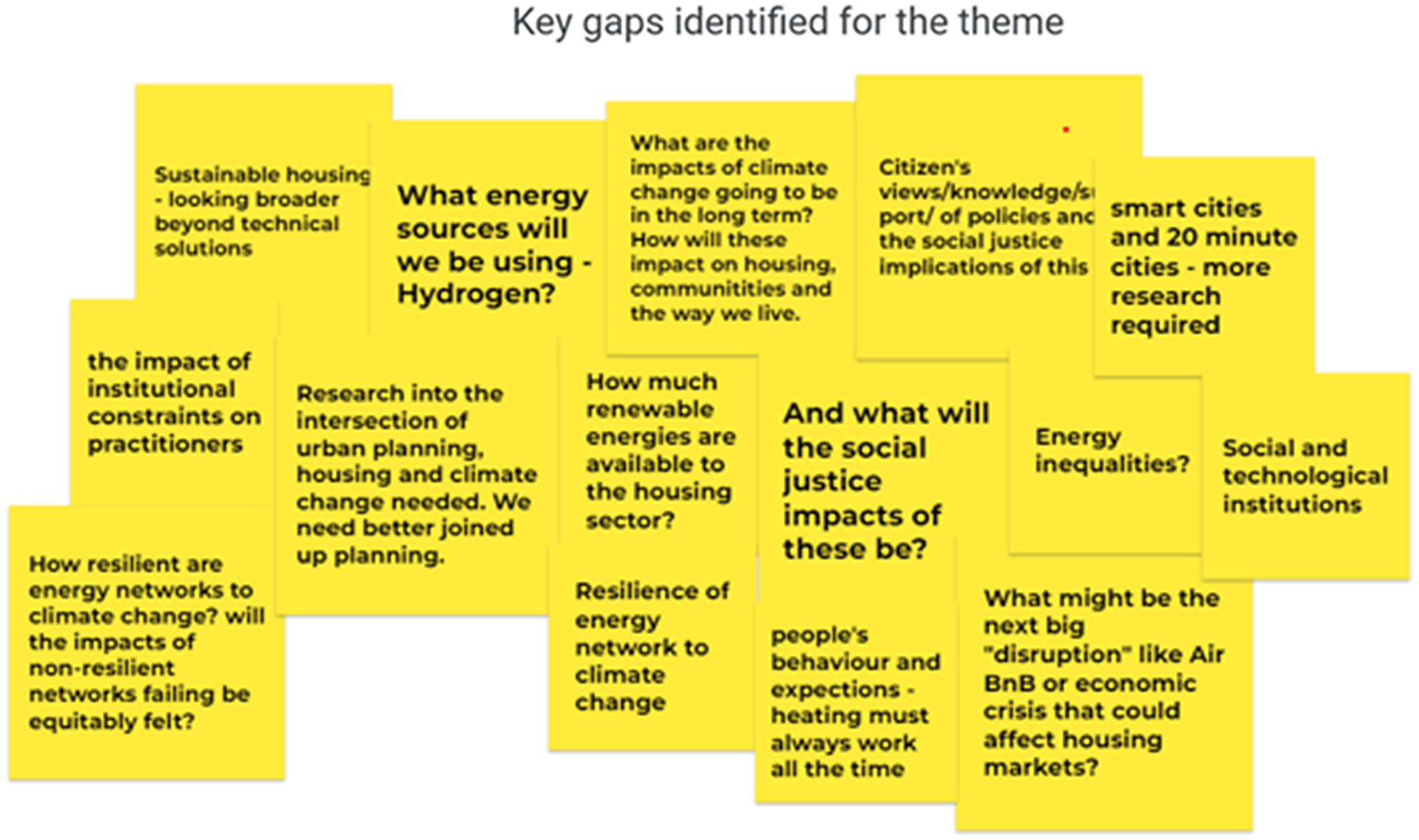

Figure 1. Gaps identified by the housing and urban regeneration group

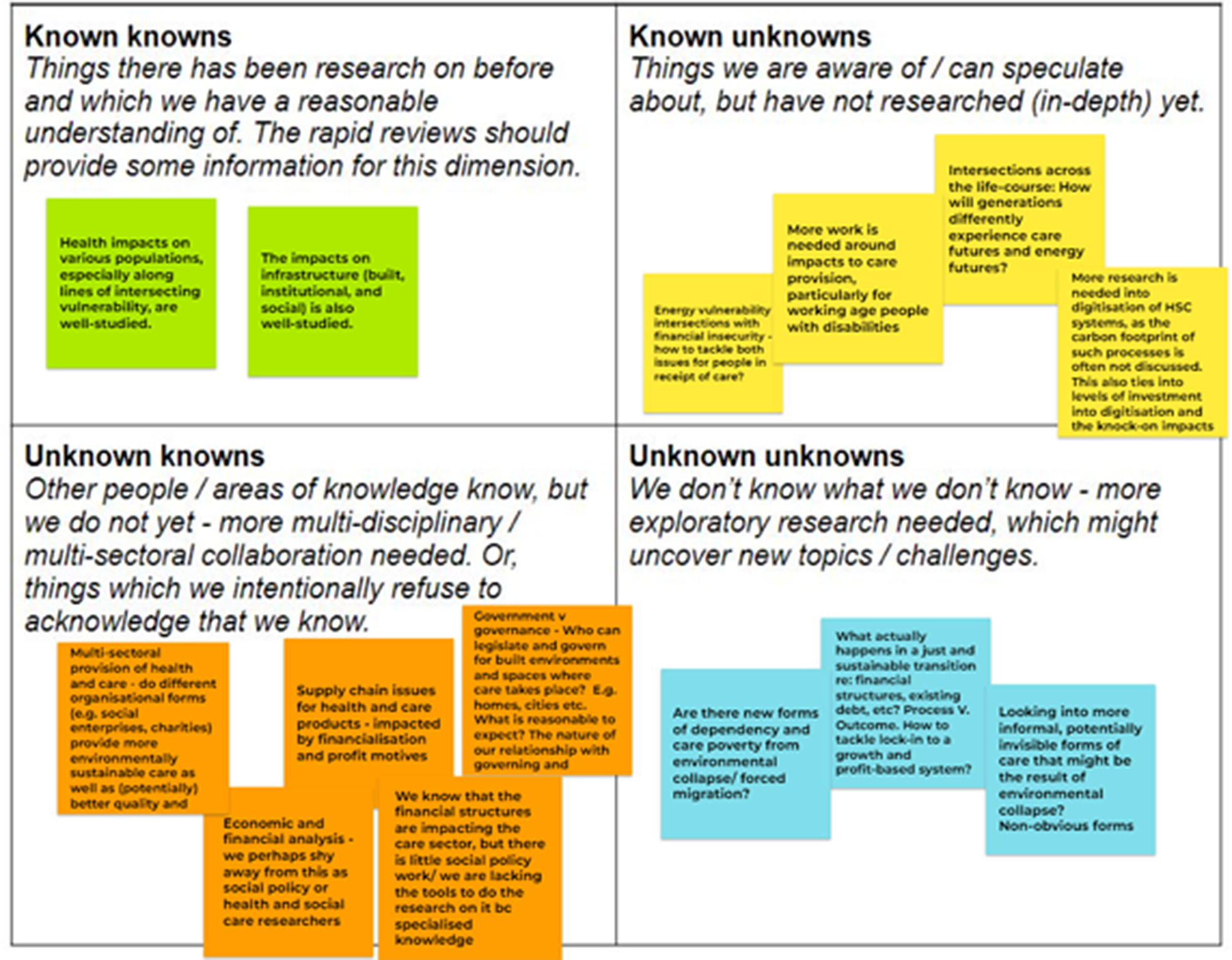

Figure 2. Completed Johari window framework for health and social care group

Findings

The section starts with the themes that speak directly to the fulfilment of basic needs (housing, energy, and water), before moving onto key areas of social policy – health, social care, employment and income maintenance, crime and criminal justice, and migration. Finally children, families and education are considered.

Housing, energy, and water

These three themes are grouped because they have strong links with each other, focusing particularly on physical infrastructure and the allocation of increasingly scarce resources. The housing and urban regeneration group identified that current literature and research focuses on ‘technical’ solutions to climate policy (e.g. retrofitting houses, installing new technology in the home, etc.), leaving some important gaps in knowledge as a result (highlighted in Figure 1). Most notable gaps identified were: the lack of knowledge about how people will interact with new technologies; whether new infrastructure and technology will cause (or reinforce) inequalities; how prepared institutions are for the changes that climate change and climate policy will present, especially given the current lack of joined up working across related policy areas (housing, planning, energy etc.); and how housing and other infrastructure will be affected by climate change (and the changes that might be necessary).

There were many similar issues raised within the fuel poverty group, although additional issues were identified. The group highlighted the relationship between energy, climate change and fuel poverty, identifying ‘win win’ policy approaches such as household energy efficiency that are able to balance both environmental and social policy objectives (as discussed in section 2). This group highlighted the impact of climate change on home energy, discussing changing heating and cooling needs, alongside greater disruption to energy supply as a result of more extreme weather events (e.g. floods). The group identified gaps in knowledge including: the extent to which vulnerable people will be able to engage with new energy systems; how new sources of fuel will work within the home; and the extent to which these challenges will disproportionately affect people along typical intersections of inequalities. Additionally, the lack of research or data amongst low- and middle-income countries, despite the importance of sustainable and reliable energy to these countries was discussed. The group also highlighted how the risks posed by climate change are exacerbated by geopolitical crises (perhaps foreshadowing the war in Ukraine and subsequent energy crisis).

The water poverty group considered the impact that water systems are likely to experience as a result of climate change, causing reduced access and reduced water quality, and risks to public health. Inequalities were highlighted with more severe effects noted in low- and middle-income countries, in rural areas, amongst Indigenous Peoples, and those in informal settlements or refugee camps. In the context of increased water scarcity fundamental questions about rights, responsibilities, and the role of the state were raised.

Health and social care

This group discussed the substantial literature linking climate change and health (for example, health inequalities work conducted by the University College London institute of Health Equity) and the intersections of inequalities associated with this. The threat of climate change to built, institutional, and social infrastructure was also discussed. The group identified key challenges and gaps in knowledge:

-

The need for more nuanced data about the impacts of climate change on vulnerable groups;

-

The need for more information about the potential impact of climate change on health and social care systems, whether these are suitable to respond to challenges created by climate change, and if they are not, what changes are necessary

-

The extent to which the health and care sector can reduce its carbon footprint.

A completed ‘Johari window’ for this group that summarises the main discussion is shown in Figure 2.

Work, employment and labour markets, and Income maintenance and social security

Discussions in these two groups overlapped substantially. The rapid reviews and initial discussions identified a number of key issues including:

-

The impact of climate change and climate policy on labour markets and employment;

-

The significance of the ‘just transition’ within international climate agreements and the importance of policymaking that enables this.

In discussing key challenges and gaps in knowledge in this area both groups asked the ‘big’ questions that perpetually underlie social policy such as ‘who pays’, ’who should benefit’ (cf. Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014; Gough, Reference Gough2017; Gough and Meadowcroft, Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Norgaard and Schlosberg2011; Huby, Reference Huby1998; and most recently, within a social policy context, reparation – i.e. who should be compensated for the damage caused by climate change (Williams, Reference Williams2021)). Additionally, more technical questions relating to the suitability of policy interventions (e.g. carbon taxes) were discussed (cf. Gough, Reference Gough2017; Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011). Whilst both groups focused heavily on those of working age, the income maintenance group also highlighted the lack of research about the relationship between pensions, climate change and climate policy. The group highlighted the domination of fossil fuel investments in pension schemes, and lack of green investment. This was considered significant in slowing decarbonisation whilst increasing risks for future pensions. Inequalities relating to income, education, age, gender, and place were identified, with concerns raised that both climate change and climate policy has significant potential to deepen these.

Migration, Crime and criminal justice

Both groups focused substantial time on climate migration and conflict, and the likelihood of this increasing both within and across borders as the climate changes and resources become scarcer. The impact of migration on origin and recipient countries was discussed (for example, on labour markets and public services) with ‘big’ questions raised about responsibility and action, questioning which states should take the greatest supportive action, and how. Discussions were also held regarding adaptation measures that might be taken to improve vulnerable infrastructure and allow communities to remain (once again this links to questions regarding who pays). A substantial concern within the migration group was the ‘elite sphere’ that was thought to dominate this field – with more bottom up data, and voices of those affected required to counter this. Further, the group highlighted a very limited ‘coherent narrative about the relationship between climate change and migration’ with existing evidence largely being case study based, and an urgent need for more systematic research. Both groups considered the human rights related issues associated with increased migration and conflict including increased child labour, domestic violence, and gender-based violence. Concerns were raised about climate migration and conflict further entrenching existing inequalities.

Beyond migration, discussions within the ‘crime and criminal justice’ group focused heavily on the concept of environmental harm (White, 2018). The group considered state and corporate harms, and the weakness of existing regulations. Patterns of environmental harm between the Global North/South, environmental racism and colonialism were also considered, with discussion about the harm caused to groups with least power (for example, Indigenous Peoples), alongside their habitual criminalisation. Finally, climate activism and civil disobedience was considered, including the United Kingdom government’s attempts to criminalise some forms of environmental activism (Public Order Act, 2023). Overall, several ‘big questions’ were raised:

-

What will crime and criminal justice in a changing climate look like and ‘who/what’ should be protected via the criminal justice system;

-

To what extent will institutions, systems, and processes need to adapt to a changing climate

-

How should states respond to environmental protesters?

Family and childhood, and Education

Discussions from the family/childhood group identified the elevated risks that children and young people face as a result of a changing climate. The group also explored evidence highlighting increased mental health impacts associated with climate change, acknowledging that at present these issues are more prevalent within the global south. The group also raised concerns that whilst children and young people are often referenced within climate change discussions, this lacks nuance– for example, by failing to recognise differences between age groups, places, and other intersecting inequalities. Related to this, there was concern about environmental narratives being overly focused on privileged groups – for example, environmental activism can often exclude those from lower incomes or people of colour. The discussion also considered how children and young people might be protected from climate change or harmful effects of policy. One proposed solution was to ensure that climate policies are assessed through the frame of children’s rights – for example, by conducting a children’s rights impact assessment on climate policies.

Discussions within the education group considered the role of climate education which the group considered underpinned many areas of social policy– for example, by ensuring a skilled labour force and climate-aware society. A number of significant challenges for the sector were raised in the discussions regarding the role of education in: fighting climate denial and encouraging sustainable lifestyles; supporting the net zero transition by enabling reskilling, retraining, and preparation for green jobs; considering different types of knowledge (e.g. traditional knowledge) within climate change education and the potential for this to be more democratic, rather than reflecting dominant narratives.

Discussion – steps needed to mainstream

Challenges arising and suggested pathways

Given the wealth of ideas generated, the workshops have set a precedent by bearing down on areas of social policy that have not always been explicitly considered in social policy-climate discourses. This section now draws together common issues, themes, and challenges discussed, with a summary of this analysis presented in Table 1.

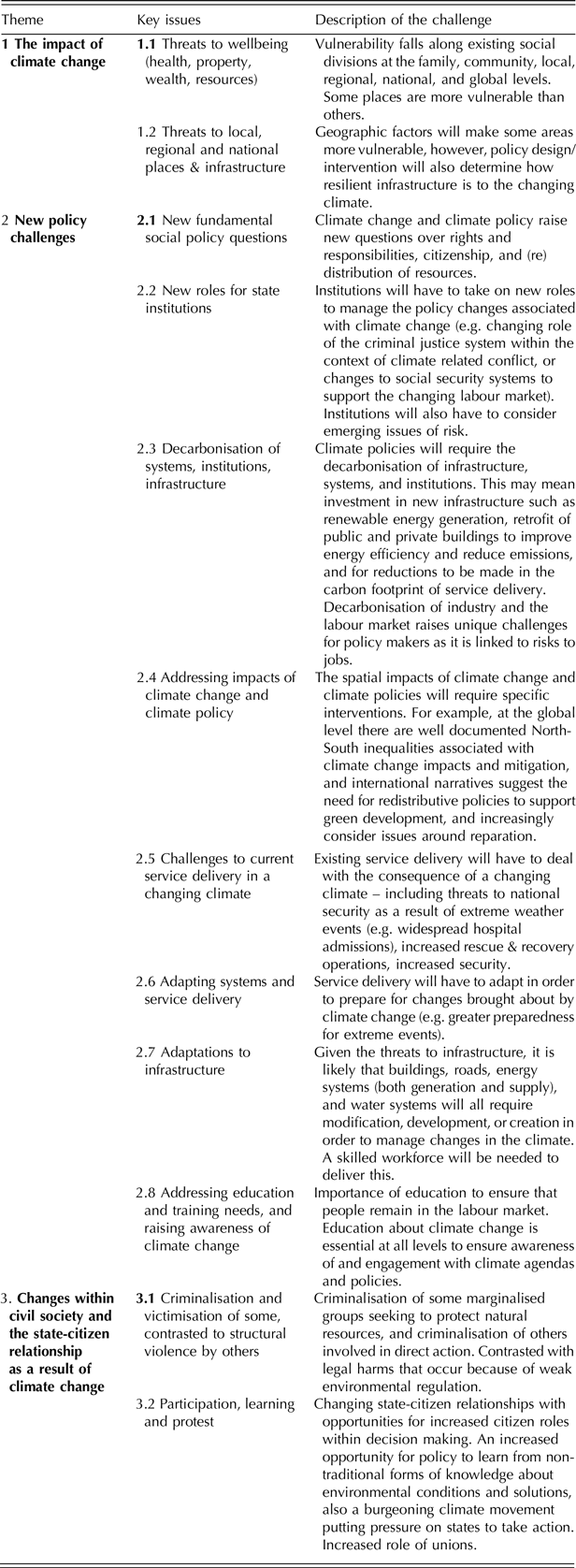

Table 1 Thematic analysis of the key challenges for social policy

A key opening observation is that some areas of Table 1 are already served well by research, across a broad range of disciplines. For example, Theme 1 ‘the impact of climate change’ is covered well by the climate justice literature (e.g. Roberts and Parks, Reference Roberts and Parks2007), and by IPCC reports (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (henceforth UNFCCC, 2022), and has also received coverage in Marmot’s work on health inequalities and climate change (Institute of Health Equity, 2020). Despite this, and the overwhelming evidence of a clear threat to everyday lives and existing infrastructure, these issues have remained limited within mainstream social policy debates and literature. This indicates an urgent need for systemic reform of knowledge generation and handling within the discipline, as Williams recognised in her 2021 call for scholars to engage in border thinking and pluriversality in the pursuit of achieving human and planetary flourishing.

Theme 2 ‘new policy challenges’ is more varied. The sustainable welfare literature emphasises the need for new systems, and inherent within this new social arrangements and policy measures (Hirvilammi and Koch, Reference Hirvilammi and Koch2020), speaking to the concerns raised in sections 2.1-2.4 of the table. Moreover, eco-social policy work that considers policy integration (e.g. Mandelli Reference Mandelli2022) and the justice orientated climate policy research (Snell, Reference Snell, Yeates and Holden2022; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022; Nordensvärd, Reference Nordensvärd2017; Williams, Reference Williams2021) can also help understand distributional impacts of policies, their underlying causes, and solutions at a range of levels. Existing social policy literature is less instructive in terms of the widespread adaptations that are necessary in the context of climate change although research can be found on the issues highlighted in 2.5-2.7 by looking beyond the discipline. For example, Balbus et al. (Reference Balbus, Berry, Brettle, Jagnarine, Soares, Ugarte, Varangu and Prats2016) and Paterson et al. (Reference Paterson, Berry, Ebi and Varangu2014) consider the resilience of healthcare facilities to climate impacts, and within policy itself there is already action being taken in terms of readiness for climate change – for example, the UK’s Local Government Association (LGA) 2020 guidance for fire and rescue services to help deal with local climate emergencies (LGA, 2020).

There is also very limited writing on the role of education and awareness raising (2.8) aside from research that highlights the significance of education in making climate policies acceptable (see Gugushvili and Otto, Reference Gugushvili and Otto2023), and factors influencing environmental attitudes (Fritz and Koch, Reference Fritz and Koch2019). Whilst wider policy debates emphasise the significance of protecting workers during decarbonisation and the significance of education and re-training (UNFCCC, 2022) a discussion of this within mainstream social policy appears missing.

Theme 3 ‘Changes within civil society and the state-citizen relationship as a result of climate change’ received little coverage in the literature reviewed in part two, however, the increasing popularity of the concept of social harm theory, and small but influential sub branch of ‘environmental harm’ that draws together green criminology with environmental justice theory (largely driven by the work of Rob White, Reference White2014) is highly informative for issues raised under 3.1.

This literature, alongside early work on sustainable development (e.g. Brundtland, Reference Brundtland1987), and climate justice work on procedural and recognition justice all provide insight into issues rasied under 3.2, however, with the exception of the work of Emilsson et al. (Reference Emilsson2022) and Williams (Reference Williams2021) there has been limited work undertaken within social policy.

The interconnected nature of the different strands of social policy can also start to be articulated – for example, education, the labour market, and the social security system will need to function together to deliver the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC)’s vision of a ‘just transition’ to net zero, compensating those affected by the loss of ‘brown jobs’, supporting re-training, and ensuring that new entrants to the labour market have the appropriate skills to enter ‘green jobs’. There is also clear interconnection between the different challenges – for example, ‘impacts of climate change’ have the potential to be either prevented or cushioned with appropriate eco-social policies (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022), and the ‘impacts of climate policy’ will be determined to some extent by wider social arrangements. For example, Gough argues for a social guarantee in the form of an eco social contract to ensure sufficient human security and well being in the context of challenges posed by climate change (2022).

In summary, multiple cross-cutting issues will affect all areas of the discipline, most notably: the need to respond to climate related challenges; the need to adapt to climate change and minimise its societal effects; and the pressures associated with the transition to a decarbonised economy. Below we further summarise these cross-cutting challenges and present pathways to guide those working in the discipline. Our pathways here suggest the need for further research, greater interdisciplinarity, the development of new methodologies and approaches to knowledge, an expansion of debates that goes well beyond the global north in focus and scholarship, and in the final recommendation, greater inclusion of climate related issues within mainstream social policy teaching.

Challenge One: Inequality and climate change remain deeply interlinked

The climate crisis will be felt unevenly, across time and space, and across existing social divisions, potentially deepening some further, especially where existing protections are limited (cf. cross border migrants, children, Indigenous Peoples). Moreover, there is an ongoing challenge of integrating and balancing environmental and social policy objectives (cf. Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022) – for example, addressing inequality without worsening environmental issues and vice versa. This has been recognised throughout scholarship on social policy and the environment (Cahill, Reference Cahill2002; Huby, Reference Huby1998; Snell and Thomson, Reference Snell, Thomson, Ramia and Farnsworth2013; Büchs et al., Reference Büchs, Bardsley and Duwe2011; Gough et al., Reference Gough, Meadowcroft, Dryzek, Gerhards, Lengfeld, Markandya and Ortiz2008; Snell et al., Reference Snell, Jenkins, Scott, Kennedy, Thomson, Yenneti, Stockton, Gough, Jolly, Cefalo and Pomati2022; Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020) and remains true today, albeit with new challenges, for example, the global energy crisis.

Suggested pathway

Improved understanding about the current risks that climate change poses to vulnerable groups, with recognition that these risks are evolving and interlinked. Specifically, we argue that social policy research can play a significant role in work that helps to understand and appropriately balance the risks of policies that have potentially negative social or environmental outcomes. Progressive, pro-active policy can indeed play an empowering and enabling role here (Mandelli, Reference Mandelli2022; Hirvilammi, Reference Hirvilammi2020). Research in this field needs to go further than it has to date, spanning different areas within social policy, recognising nuance and intersectionality, and that impacts of both climate change and climate policy may be temporally and spatially varied. Whilst we lack the space here to discuss in detail the numerous groups that might need specific attention, we instead highlight the need to recognise contexts, difference, and intersectionality. For example, the specific needs of children and future generations, and the potential value of rights based approaches.

Challenge two: The climate crisis poses an existential crisis for the discipline of social policy

Within the workshops discussions it was clear that there is a lack of accessible conceptual work around the ‘big’ questions raised concerning the new state-citizen arrangements, rights, and responsibilities. Thinking about these questions is essential to prepare us for the changes that will occur in tandem with climate change including: the protection and/ (or?) policing of climate migrants, how to respond to the changing labour market, and whether greater protections for some groups need to be further embedded into institutions and policy responses. There remains a lack of more specific, technical analysis of what responses are needed, and how they might work (for example, how labour market social protection packages might work best in different contexts). Whilst the formative literature in this area raised this challenge (e.g. Gough, 2014, Reference Gough2017; Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014) we suggest a far deeper, more immediate need for the discipline to respond to this.

Suggested pathway

More theoretically driven work is needed in order to help understand how social policy might respond to the ‘big’ questions such as the role of social policy within the climate crisis, and citizens’ rights and responsibilities within this changing context. Here research on Sustainable Welfare and Eco Social Policy (and indeed related concepts) are key – given their critique of existing approaches to welfare states and systems, challenges to the emphasis on growth, and often transformative outlook. There is also an opportunity to build on the burgeoning citizenship literature (see Dwyer, Reference Dwyer2010), or indeed the growing literature on environmental protest and criminalisation (White, 2018). In addition to this, there is a need for more applied research considering specific policy approaches to climate change and climate policy across the areas considered by social policy, for example, understanding how the labour market, social security system, and education can best support the changes in jobs associated with the net zero transition.

Challenge four: Some areas of social policy have considered the climate crisis more than others

Different areas of social policy are at different points in terms of existing knowledge, data, policy and practice. Whilst the housing, energy, water, and employment fields have engaged with the climate agenda for some time, in part due to international agendas (e.g. the just transition narrative that emerged from the Paris Agreement in 2015 has led to an uptick in interest in what climate policies might mean for labour markets), and also given that these are already exposed to the effects of climate change and broader geo-politics (e.g. energy), other areas are less developed. For example, the field of pensions remains in its infancy, and the debates emerging from crime and criminal justice, children and young people, and migration currently lack nuance despite raising extremely important, often urgent, questions.

Suggested pathway

We urge scholars in fields such as children and young people, education, social security, health and social care, crime and criminal justice, and migration to fill these gaps in knowledge as a matter of urgency, drawing on learning from other fields and disciplines. As discussed above, there is a pressing need to both adapt and decarbonise, ensuring that policy is preventative where possible, reactive where necessary, and does not add to the harm caused by climate change.

Challenge five: The climate change and social policy literature remains focused on the global north and has a narrow understanding about what constitutes ‘knowledge’

At present existing knowledge tends to focus on the global north drawing on quite specific types of ‘acceptable’ evidence. There is a need for a broader evidence base, that considers alternative forms of knowledge, and that recognises global inequalities (e.g. the enduring impact of colonialism). Whilst early social policy-environment literature raised the importance of the focus of research and debate (e.g. Fitzpatrick, Reference Fitzpatrick2014), substantial changes have occurred since these early discussions, and it is important to reflect this, building on Williams’ (Reference Williams2021) work for example.

Suggested pathway

As a start we suggest that the decolonisation of research and publishing agendas is accelerated, alongside a greater engagement with and understanding of different types of knowledge and knowledge creation, proactive investment in research from the global south (including but not limited to: skills, funding, platforms).

Challenge six: There is a significant, so far underutilised, role for social policy educators

Our discussions raised important questions about how climate change should be taught within education settings, and the role of education providers in supporting the new skills and training required for the labour market. They also raised questions about how climate change education can be embedded within social policy curricula at the Higher Education level, something that is often neglected. A call here is to all social policy teaching academics – climate change debates are not just for COP season, but are fundamentally related to all aspects of mainstream social policy teaching. We have seen no scholarship in this area previously, despite the increased recognition of children and young people’s climate literacy and activism (cf. Gasparri et al., Reference Gasparri, Omrani, Hinton, Imbago, Lakhani, Mohan, Yeung and Bustreo2021).

Suggested pathway

Recognise the importance of embedding issues of climate change into the social policy curriculum, and the role that social policy departments within Higher Education can play within this. Here we also highlight the importance of decolonising the curriculum – as a global issue, climate change often has far reaching impacts in the global south, but rarely are forces of colonialism and neo colonialism recognised within these debates. Here, the emerging environmental harm literature may allow a more critical lens to be applied.

Conclusion

We started this paper by outlining the climate crisis, and we conclude with a call to arms. The pathways identified above stem from our discussions with over 100 social policy scholars. As a collective, these workshops identified existing progress in the field, but also areas where climate change has had little or no traction. As such, we have argued that there is an urgent need for new research that is embedded in an openness for different types of knowledge and data, that is interdisciplinary, that considers the impact of climate change and climate policy on societies, that considers the conceptual, existential questions raised by this threat, and builds applied, contextualised policy and practice pathways to help navigate these challenges. Not only is there a central role for social policy scholars as we manage the climate crisis, but so too for social policy teaching and learning. Arguably mainstreaming climate change within our teaching will have an enduring, normalising effect on the discipline.

Acknowledgements

The support of the Social Policy Association in funding our Climate Justice and Social Policy group is gratefully acknowledged. We would also like to thank our workshop participants for their time and ideas, with specific thanks to the following people who supported with facilitating the workshops: Karla Ricalde, Anna O’Connor, Lisa O’Malley, Ruth McKie, Lee Gregory, Gill Main, Anne Luke, Kelli Kennedy, Lucie Middlemiss, Matthew Lariviere, Becky Ince, Peter Matthews, Paul Bridgen, Jennifer Allsopp, Jess Cook, Elke Heins, Meron Fikru, Evandro Coggo, Emma Thackray, David Beck, Courtney Stephenson, Katie Zwerger, Trudi Tokarczyk, Larissa Nenning, Natasha Nicholls, Angus Lee, Yongxin Ye.