1 Introduction

Sahaptin is a Sahaptian language spoken in Washington and Oregon, U.S.A. Rigsby & Rude (Reference Rigsby, Rude and Goddard1996) divide Sahaptin into three broad dialect areas: Northwest, Northeast, and Columbia River.Footnote 1 This Illustration of the IPA reflects the Yakama (also spelled Yakima)Footnote 2 subdialect (ykm) of Northwest Sahaptin. Sahaptin has fifty or fewer native speakers (Beavert & Jansen Reference Beavert and Jansen2012). The second author is a native speaker of this dialect. Her voice is on the accompanying recordings.

Sahaptin grammars include Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1931), Rigsby & Rude (Reference Rigsby, Rude and Goddard1996), and Jansen (Reference Jansen2010). For Northwest Sahaptin in particular, Pandosy (Reference Pandosy1862) is a grammar-dictionary, Griva (no date) and Beavert & Hargus (Reference Beavert and Hargus2009) are dictionaries, and Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1929, Reference Jacobs1934, Reference Jacobs1937) are text collections. Jansen (Reference Jansen2010) also includes three texts by the second author of this article.

Sahaptin and Nez Perce are the only two languages in the Sahaptian family (Aoki Reference Aoki1962). Sahaptian was once thought to be a branch of Plateau Penutian (Sapir Reference Sapir1929), along with Cayuse, Molala and Klamath. Although the Plateau Penutian hypothesis is now generally discredited, following Rigsby (Reference Rigsby1965), there is some evidence that Klamath and Sahaptian are historically related (Aoki Reference Aoki1963; Rude Reference Rude1987, Reference Rude, Traugott and Heine1991; DeLancey, Genetti & Rude Reference DeLancey, Genetti, Rude and Shipley1988; DeLancey Reference DeLancey1992).

2 Consonants

The consonant inventory of Sahaptin is typical of languages in the Plateau linguistic area (Kinkade et al. Reference Kinkade, Elmendorf, Rigsby, Aoki and Walker1998). Ejective and non-ejective stops and affricates contrast at several places of articulation.

The marginal segment [ʁ] is discussed in Section 2.2 below.

The Sahaptin plosives, though phonemically unaspirated, could be described as lightly aspirated. Grossblatt (Reference Grossblatt1997) studied the pre-vocalic contrast between /p’ t’ k’ k’w q’ q’ w / and their plosive counterparts in word list recordings produced by the second author. Some of his findings are shown in Table 1, where it can be seen that relative to plosives, ejectives have long VOT, a clear silent period, and elevated f0 at vowel onset. (f0 averages were calculated for this article from data provided in Grossblatt's (Reference Grossblatt1997) Appendix C.) The VOT and f0 differences were significant (VOT, p < .0001; f0, p = .0184).

Table 1 Some phonetic characteristics of Sahaptin plosives and ejective stops (Grossblatt Reference Grossblatt1997).

2.1 Examples

Where possible, each consonant has been illustrated before accented [a].

2.2 Low type frequency consonants

/ʁ/ has been found in only one morpheme, shown in 2.1. This sound has not been listed in any previous consonant inventory of Sahaptin.

The velar and labial velar fricatives /x x w / are found in relatively few morphemes, as noted by Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002a). However, there are a few near-minimal pairs for /x/ vs. /χ/ and /x w / vs. /χ w /:

2.3 Secondary articulations

As seen in the Consonant table above, labialization is considered a secondary articulation of velars and uvulars. The labial dorsals are analyzed as unit phonemes because like the plain velars and uvulars, they can occur in word-final position:

No other consonants can precede [w] in word-final position.

Labial dorsals pattern with dorsals in word-initial position. Both can be directly followed by a consonant:

In contrast, word-initial [w] cannot be followed directly by any consonant except [j] (see Section 2.5 below), but instead undergoes ɨ-epenthesis in this context:

As the second member of a word-initial cluster, [w] must be followed by a vowel, not a consonant, unlike the labial component of a labial dorsal.

2.4 Contextually limited contrasts

Contrasts between [ʔ] and Ø occur only word-internally and (somewhat rarely) word-finally:

Word-initially, [ʔ] is predictable before a vowel, as in [ʔiˈt’ɨχ w t’χ w ʃa] ‘it's raining’ (/iˈt’ɨχ w t’χ w ʃa/).Footnote 6

Contrasts between the voiceless unaspirated plosives and ejectives occur mainly before vowels or sonorant consonants:

However, some contrasts are found before obstruents:

Even more rarely, contrasts also occur word-finally. All examples of word-final ejectives are found in onomatopoetic words:

2.5 Phonotactics

The Sahaptin syllable requires an onset consonant and permits both onset and coda clusters. As noted by Rigsby & Rude (Reference Rigsby, Rude and Goddard1996: 671), ‘the clustering of consonants shows few restrictions and is common’. In Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b), we suggested that word-internal consonant clusters are generally limited to two consonants. Longer sequences can occur at word edges.

Word-initial clusters distinguish Sahaptin even from its closest relative Nez Perce, which disallows word-initial consonant clusters. Restrictions on consonant sequences were discussed and exemplified in Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b), a qualitative acoustic study, where we suggested that unstressed [ɨ] is inserted to break up certain kinds of clusters.Footnote 7 This inserted [ɨ] is predictable from the length of the cluster and the major classes of segments which comprise the cluster. Further discussion of properties of onset and coda clusters, including place restrictions within onset but not coda clusters, can also be found in Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b).

Some of the properties of bisegmental word-initial clusters are described and exemplified in this section. First, a summary is provided in Table 2, which uses a slight expansion of the rows of the Consonant table above. (Note that the sequence semi-vowel + lateral approximant occurs in a trisegmental, but not bisegmental, initial cluster.)

Table 2 Pronunciation of underlying sequences of consonants.

Examples of bisegmental clusters (without epenthetic [ɨ]) are provided next. All examples in this section are monomorphemic unless otherwise indicated.

The cells in Table 2 which surface with [ɨ] between the two consonants and those which surface as is (without [ɨ]) are in complementary distribution. For this reason, we treat [CɨC] as underlyingly /CC/. Examples of these underlying bisegmental clusters which consistently surface with epenthetic [ɨ] are provided next:

In the three contexts of Table 2 where some cells surface with or without epenthetic [ɨ], the first consonant is always nasal. Two further generalizations are possible, maintaining the predictability of [ɨ] in such clusters:

-

(i) When the second consonant is the semi-vowel [j], there is no ɨ-epenthesis. The following sequences occur:

-

(ii) Otherwise, when the initial nasal is [m], then ɨ-epenthesis always occurs. However, [n] surfaces in sequence with the following consonant, except when the following consonant is a labial dorsal:

Here we see that the labial dorsals, although single consonants with respect to word final distribution and some aspects of word-initial distribution (§2), behave like consonant sequences in other ways in initial clusters. In longer initial clusters, i-epenthesis is more frequent. Compare /ʃm/ followed by a vowel in [ˈʃmat’a] shmát’a ‘wash face’ vs. /ʃm/ followed by a consonant in [ʃɨmˈtaj] shɨmtáy ‘pubic hair’. See Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b) for further examples of i-epenthesis in triconsonantal and longer clusters.

Turning briefly to the laryngeal consonants, [h] does not occur in clusters. [ʔ] may occur as the first consonant in a cluster, where it is always followed by [ɨ]:

For further details on initial and final clusters, see Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b).

3 Vowels

3.1 Vowel quality contrasts

There are four contrasting vowel qualities, all found root-internally:

Although [ɨ] occurs root-internally like the other vowels, the distribution of [ɨ] differs from that of the other vowels in certain ways. [ɨ] does not occur root- or word-finally, is the only vowel with no long counterpart (3.3), and does not occur before semi-vowels (3.4) except in initial clusters (3.3).

3.2 Spectral properties

An acoustic chart of the four contrasting vowel qualities of Sahaptin is shown in Figure 1 below. This figure is based on measurements of the words in Table 3 (ten tokens per quality).

Figure 1 F1 × F2 plot of short vowels (tokens, means and 95% confidence intervals).

Table 3 Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of F1 and F2.

Comparing Figure 1 with the IPA vowel chart, [ɐ] would be a more accurate symbol for the low vowel than [a] in a narrow transcription, since the second formant of the low vowel is intermediate between that of back [u] and central [ɨ]. In the broader transcription used in this Illustration, the symbol [a] is used to show parallelism between the short and long vowels: each peripheral vowel has a long counterpart (3.3).

The vowel [ɨ] was transcribed [ə] by Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1931). However, following Rigsby (Reference Rigsby1965), we use [ɨ] for this vowel. As can be seen in Figure 1, this vowel is relatively close in F1 to [i] and [u], although in the sample plotted in Figure 1, [i] and [u] each has significantly lower F1 than that of [ɨ] (by the Bonferroni Dunn post hoc test). A more accurate symbol for the central vowel might therefore be [ɘ] or perhaps [

![]() ]. In support of our broad transcription of this vowel as [ɨ], we note that [ɨ] patterns with [i

u] rather than [a] in undergoing Destressed High Vowel Deletion (Hargus & Beavert Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b). When accent (4.1) shifts leftward (as when an accented prefix is added to an accented root, when a root is reduplicated, and in some compounds), the root accent is deleted. When [i

u] are adjacent to a homorganic glide within a root, these vowels are deleted when deaccented:

]. In support of our broad transcription of this vowel as [ɨ], we note that [ɨ] patterns with [i

u] rather than [a] in undergoing Destressed High Vowel Deletion (Hargus & Beavert Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b). When accent (4.1) shifts leftward (as when an accented prefix is added to an accented root, when a root is reduplicated, and in some compounds), the root accent is deleted. When [i

u] are adjacent to a homorganic glide within a root, these vowels are deleted when deaccented:

Like the other high vowels, [ɨ] also deletes when deaccented (and followed by one or more obstruents):Footnote 13

Although the contexts for unstressed /i u/ deletion vs. unstressed /ɨ/ deletion are different, note that [a] does not delete in any context. Compare the retention of [a] in ‘ring it’ with the deletion of [ɨ] in ‘Eel Trail’:

3.3 Vowel length

As noted above, all vowel qualities but [ɨ] can occur long or short.

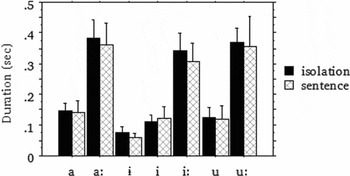

Rigsby & Rude (Reference Rigsby, Rude and Goddard1996: 667) describe [ɨ] as ‘invariably shorter in duration than the other short vowels’. One- or two-syllable words containing the second author's seven contrastive vowels in closed syllables were recorded in isolation and also in a sentence frame. Average durations and standard deviations for the seven contrastive vowels of Sahaptin are shown in Figure 2. This figure is based on measurements of the vowels of interest in the words (four repetitions per word) in Table 4.

Table 4 Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) for vowel duration in two contexts.

Figure 2 Vowel durations (averages and standard deviations) in two contexts.

Across both contexts, the average duration for [ɨ] is 68 msec, for short vowels [i a u] 128 msec, and for long vowels [iː aː uː] 354 msec. Post hoc analysis (Bonferroni Dunn) showed that [ɨ] was significantly shorter than each of [i a u], thus confirming Rigsby and Rude's statement above. [i a u] did not differ significantly from each other in duration. Each of [i a u] was significantly shorter than each of [iː aː uː]. Of the long vowels, [iː] was significantly shorter than [aː], but there were no other significant differences in duration among the long vowels.

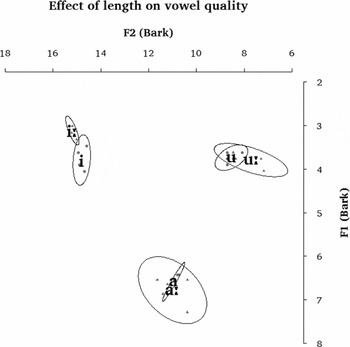

Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1931: 100) noted that [i u] are more ‘open’ than their long counterparts. Spectral analysis of short vs. long vowel qualities, in Figure 3, shows that long vowels are more peripheral in the vowel space than corresponding short vowels, although the only significant differences in F1 are between [i] and [iː], and for F2, [i] vs. [iː] and [u] vs. [uː] (Bonferroni Dunn). Figure 3 is based on measurements of the vowels of interest in the words shown in Table 5 (five repetitions per word).

Figure 3 F1 × F2 plot of short (non-central) vs. long vowels (tokens, means and 95% confidence intervals). Short vowel tokens are plotted with dots, and long vowels with triangles.

Table 5 Means and standard deviations (in parentheses) of F1 and F2 for long and short vowel contrasts.

3.4 Vowel and semi-vowel combinations

In contrast to consonant sequences, vowel sequences in Sahaptin are strictly disallowed. Tautosyllabic closing ‘diphthongs’ are attested, but these are arguably simply long or short vowels followed by a semi-vowel.Footnote 14 The only distributional restriction on ‘diphthongs’ is that in a high vowel + semi-vowel combination, the vowel and semi-vowel must be of opposing labiality. All of the vowels except [ɨ] (as noted above) can occur long or short before semi-vowels.

Minimal and near-minimal pairs for [iw] and [ju], [wi] (or [ w i]) and [uj] are shown next:

Note also that [iji] contrasts with [iː]:

[uwu], on the other hand, does not occur in Northwest Sahaptin.

4 Prosody

4.1 Lexical pitch accent

The prosodic system of Sahaptin fits the characteristics of what is usually described as pitch accent (see e.g. McCawley Reference McCawley and Fromkin1978). Sahaptin morphemes are either underlyingly accented or unaccented. Unaccented free morphemes are a small set, including function morphemes such as conjunctions [ku] ‘and’ and [uː] ‘or’:

Because of the existence of unaccented free morphemes, we transcribe accent on monosyllables in this article and in our other work.

Unaccented bound morphemes are more common than unaccented free morphemes. The unaccented bound morphemes include pronominal clitics:Footnote 15

Unaccented bound morphemes are a source of accent contrasts in polymorphemic words. Words surface with one accent.Footnote 16 As described by Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2002b, Reference Hargus, Beavert, Baumer, Montero and Scanlon2006a), if a word contains both an accented prefix and an accented root, the accent surfaces only on the prefix, as in [ˈmajkuːkit] ‘morning cooking’ and [ˈpaʔɨna] ‘3sg told 3sg’, the morphological decomposition of which is shown next:

(However, Hargus & Beavert Reference Hargus, Beavert, Baumer, Montero and Scanlon2006a noted that some roots, termed ‘strong roots’, resist the attraction of accent to a prefix.Footnote 17 ) Accented suffixes either realize their accent on a vowel of the suffix (e.g. -ɬá ‘agent’) or are pre-accented, with the accent realized on the syllable before the suffix (e.g. -ˊɬam ‘malevolent agent’). If a word contains both an accented suffix and an accented root, the strongest accent in the word is on the suffix, as in [paˈχ w iɬam] or [pamʃpaχ w iˈɬa]:

-

[paˈχ w iɬam] ‘thief, burglar’

-

pá x wi-ˊɬam

-

steal-mal.agt

-

compare [ˈpaχ w i] páxwi ‘steal’

-

[pamʃpaχ w iˈɬa] ‘eavesdropper’

-

pá-mɨshpá x wi-ɬá

-

inv-eavesdrop-agt

-

compare [mɨʃˈpaχ w i] mɨshpáxwi ‘eavesdrop’

Minimal pairs for accent location can also be found in polysyllabic, monomorphemic roots:

Compounding is not a common word-formation strategy in Sahaptin, but compounds are sometimes distinguishable from homophonous phrases by virtue of the fact that the compound contains only one accent:

([ʔaˈsumʔɨ

![]() t] (Asúm ɨshcht) ‘Eel Trail’ in 3.2 is another example of a compound with one accent.)

t] (Asúm ɨshcht) ‘Eel Trail’ in 3.2 is another example of a compound with one accent.)

Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1931: 117) noted that ‘stress and high tone are one phenomenon in northern Sahaptin; they are very strongly marked in northwest Sahaptin’. Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus, Beavert, Jinguji and Moran2005) determined that the principal phonetic correlates of accent are increased pitch and energy, but not duration. Figure 4 Footnote 19 shows the relative quality of accented vs. unaccented vowels. While there is a tendency for F1 to be higher for accented vowels, the effect of accent on F1 was not significant in this sample.

Figure 4 F1 × F2 plot of accented vs. unaccented vowels (means).

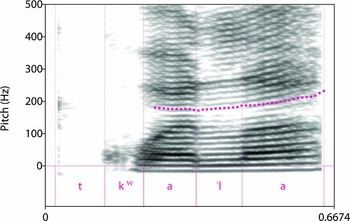

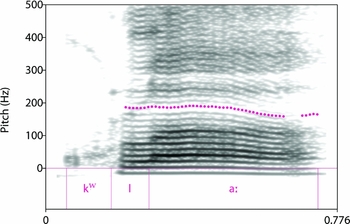

Jacobs (Reference Jacobs1931: 117) further noted that accented ‘short vowels have high tone’ and that ‘long vowels or diphthongs in accented syllables have falling tone, high to normal’. We have found both of these statements true of the second author's word-final accented vowels. Figure 5 contains a word which ends in a short, accented vowel. Note the lack of pitch fall at the end of the word. In contrast, Figure 6 contains a word-final accented long vowel. Note the fall in pitch.

Figure 5 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [tk w aˈla] tkwalá ‘freshwater fish'.

Figure 6 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈk w laː] ‘slight'.

4.2 Intonation

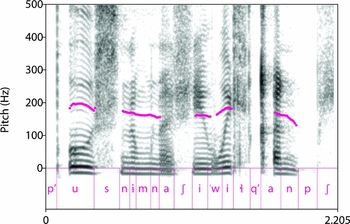

In declarative sentences, the lowest pitch of the sentence is at its right edge if the sentence does not end in a short accented vowel, suggesting that declarative sentences are marked by an intonational low (L) boundary tone. (The word-final fall on long vowels as seen in Figure 6 can then also be considered an instance of this declarative L.) An example of the lowest pitch occurring sentence-finally is presented in Figure 7. The sentence in Figure 7 contains two lexical pitch accents, on the syllables [p’uːs] (197 Hz) and [wi] (184 Hz). The lowest sentence-internal pitch is on the syllable [naʃ] at 154 Hz, and the pitch drops to 135 Hz at the end of the sentence.

Figure 7 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈp'uːsnɨmnaʃ iˈwiɬq'anpʃ] Ɨp'úusnɨmnash iwíɬk'anpsh ‘The cat scratched me'.

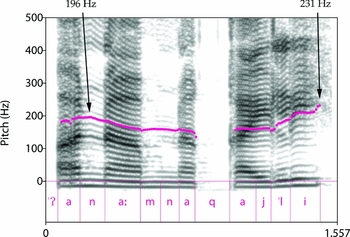

Declarative L boundary tone never overrides or concatenates with a sentence-final lexical pitch accent. Just like words in isolation (Figure 5), if the sentence ends in a lexical pitch accent, there is no final pitch fall at the end of the sentence. An example is provided in Figure 8, where the similarity of the highest pitches in each word and lack of sentence-final L can be observed.

Figure 8 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈʔanaːmna qajˈli] Ánaamna kaylí ‘His/her shoe wore out'.

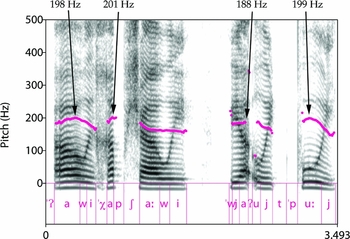

As noted by Hargus & Beavert (Reference Hargus and Beavert2009), the pitch peaks of declarative sentences are determined largely by lexical pitch patterns. In Figure 9, which contains a sentence-final long vowel, notice the similar pitch level of the lexical pitch accents in each word. (Declarative L boundary tone can also be seen in Figure 9.)

Figure 9 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈʔaw iˈχapʃaːwi ˈwjaʔujt ˈpuːj] Áw ixápshaawi wyá'uyt púuy ‘Now the first snow has fallen'.

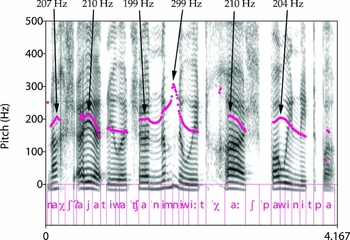

Two kinds of deviations from lexical pitch accents, both involving elevated pitch, have been identified:

-

(i) Elevated pitch excursion can be used for semantic emphasis. In Figure 10, note the raised pitch (299 Hz) on [ˈnɨmnɨwiːt] ‘really’ relative to the other lexical pitch accents.

-

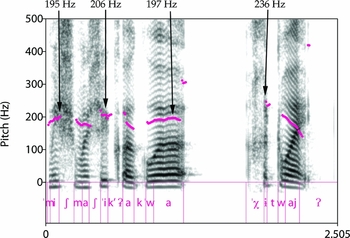

(ii) Yes/no questions can be marked by elevation of the rightmost pitch accent of the sentence, as in Figure 11.

Figure 10 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈnaχʃ ˈʔajat

iwa

![]() a ˈnɨmnɨwiːt ˈχaːʃ ˈpawinitpa] Náxsh áyat iwachá n

a ˈnɨmnɨwiːt ˈχaːʃ ˈpawinitpa] Náxsh áyat iwachá n

![]() mnɨwiit xáash páwinitpa ‘One woman was really aggressive at the give-away'.

mnɨwiit xáash páwinitpa ‘One woman was really aggressive at the give-away'.

Figure 11 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈmiʃmaʃ ˈik'ʷak ˈwa ˈχɨtwajʔ] Míshmash íkw'ak wá

x

![]() tway'? ‘Is that your relative?'.

tway'? ‘Is that your relative?'.

Yes/no questions are alternatively optionally marked by a sentence-final glottal stop, also seen in Figure 11. Sahaptin glottal stop frequently exhibits widely spaced glottal pulses, and would thus be expected to depress pitch. However, like sentence-final declarative L, final glottal stop does not override sentence-final lexical pitch accent, as seen in Figure 12. (This sentence also illustrates the optionality of rightmost pitch accent raising in yes/no questions: in Figure 12 the sentence-final lexical accent is not the highest pitch in the sentence.)

Figure 12 Narrow band spectrogram and pitch track of [ˈmiʃpam ˈχtwajakʃana waˈtimʔ] Míshpam xtwáyakshana watím'? ‘Did you (pl) come to visit me yesterday?'.

5 Transcription

-

1.

-

2.

-

3.

-

4.

-

5.

-

6.

-

7.

-

8.

-

9.

Acknowledgements

We thank two anonymous JIPA reviewers for the time they took to prepare helpful comments which improved the quality of this article. For research support we thank the Jacobs Research Funds (2009–2014, to Hargus and Beavert) and Native Voices Endowment (2010–2014, to Beavert).