Introduction

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) involve enhancing and working with nature to address various societal challenges such as biodiversity loss and climate change (Bauduceau et al., Reference Bauduceau, Berry, Cecchi, Elmqvist, Fernandez, Hartig, Krull, Mayerhofer, Sandra and Noring2015). NbS include, but are not limited to the incorporation of green and blue infrastructure in urban and rural areas (Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Chausson, Berry, Girardin, Smith and Turner2020). Recently, NbS have been embraced within diverse urban contexts as a pathway for improving the environmental conditions, climate-resilience and overall health of urban communities. Therefore, they are often approached as technical, interventions that will deliver equity and justice goals (Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). Evidence, however, consistently shows that the added value NbS generate is highly differentiated and stratified by geography, ethnic groups and socio-economic status (Curran and Hamilton, Reference Curran and Hamilton2012; Pearsall, Reference Pearsall2012; Anguelovski et al., Reference Anguelovski, Connolly, Masip and Pearsall2018; Kabisch, Reference Kabisch2019). Working-class and minority populations typically bear the brunt of this inequality. Such groups more frequently have housing opportunities in areas with fewer, and lower quality, urban green and blue spaces when compared to upper class populations. Moreover, higher income groups are historically privileged when it comes to access to, and control over urban green and blue spaces (Wolch et al., Reference Wolch, Wilson and Fehrenbach2005; Heynen et al., Reference Heynen, Perkins and Roy2006; Landry and Chakraborty, Reference Landry and Chakraborty2009; Park and Pellow, Reference Park and Pellow2011).

Thus, the impacts of NbS are not so straightforward. Ever increasing evidence demonstrates that NbS can perpetuate inequalities and potentially give rise to new forms of exclusion since the process of designing and implementing NbS is embedded within the broader societal context (Tozer et al., Reference Tozer, Hörschelmann, Anguelovski, Bulkeley and Lazova2020). NbS are a product of local social structures and can include underlying inequality and injustice based on gender, class, sexuality, age, ability and ethnicity. Moreover, NbS often occur in public spaces and their design and implementation are shaped by complex power relations. As a result, NbS are inherently political and must be tackled accordingly (Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). Hence, acknowledgement of such necessitates deeper inquiry into the design and implementation of NbS to address the perpetuation of unanticipated injustices and inequitable power structures.

The above mentioned inequalities are not merely coincidental. On the contrary, they can be seen as symptoms of oppressive political, economic, and institutional forces at all levels of socio ecological systems (Bronfenbrenner, Reference Bronfenbrenner1977; Fornili, Reference Fornili2022). Oppression is defined as “discrimination backed up by systemic or structural power” and involves biased information, stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination (McGibbon, Reference McGibbon2021). Hence, critical consciousness should be raised among these marginalized and oppressed populations (Freire, Reference Freire1978; Jemal, Reference Jemal2018). Critical consciousness involves awareness among marginalized populations about their marginalized status as well as liberating action against forces that limit or promote opportunities for certain groups (Freire, Reference Freire1978; Jemal, Reference Jemal2018). Participatory approaches could be a pathway through which to achieve critical consciousness (Abma et al., Reference Abma, Banks, Cook, Dias, Madsen, Springett and MT2019). However, participatory approaches in NbS have often failed in terms of inclusion, degree of democracy achieved and accessibility (Fainstein, Reference Fainstein2011; Certoma et al., Reference Certoma, Corsini and Rizzi2015). Therefore, it is fundamental to establish a new comprehensive approach to ensure that adequate levels of inclusion are achieved and pave the way for transformative change. Designers and implementers of NbS must ask themselves the following questions: why are NbS being implemented? By, for and with whom are NbS implemented? Who does the monitoring and how? Who reaps the benefits of NbS? These questions are essential if NbS are to work towards and not against justice.

This paper proposes an integrated theoretical framework for incorporating an intersectional understanding of gender, inclusion, and diversity (GID) into the design of future NbS, operationalizing the framework with a checklist that supports enhanced GID considerations in the full cycle of NbS creation. As the need for social, cultural and gender equity and inclusiveness has been defined as one of the nine Network for Ecohealth and One Health updated competencies for One Health (Wallace et al., Reference Wallace, Bergmann, Kock, Gilbert, Hogerwerf, Wallace and Holmberg2015; Garnier et al., Reference Garnier, Savić, Cediel, Barato, Boriani, Bagnol and Kock2022; Laing et al., Reference Laing, Duffy, Anderson, Antoine-Moussiaux, Aragrande, Luiz Beber, Berezowski, Boriani, Canali and Pedro Carmo2023), this framework is rooted in an overall One Health approach that aims to link and understand social and ecological determinants of health through a transdisciplinary approach (Keune et al., Reference Keune, Flandroy and Thys2017, Reference Keune, Kretsch and Oosterbroek2018). Hence, both academic – from several disciplines – and non-academic partners were involved in the creation of the proposed framework. For the development of this framework, we particularly focused on the context of European urban areas.

Methods

General approach

Putting GID on the agenda: creating the panel

Within the Horizon 2020 GoGreenRoutes (GGR) consortium a GID panel was established. GGR is a transdisciplinary consortium of 40 organizations aiming at implementing NbS in six European cities: Burgas (Bulgaria), Lahti (Finland), Limerick (Ireland), Tallinn (Estonia), Umeå (Sweden) and Versailles (France). The GID panel is a transdisciplinary panel consisting of GGR consortium partners possessing professional experience and commitment to the broader concept of diversity. The panel emerged spontaneously among a number of individuals across consortium partners and aimed to put GID on the agenda within the consortium’s activities in the partner cities. Therefore, the purpose of the GID panel was to actively develop a strategy to integrate diverse perspectives into the co-creation and co-evaluation processes of NbS employed by the cities partnering with the consortium. Panel participants mapped existing challenges and shortcomings within the consortium. Subsequently, relevant resources were identified, including both scientific resources and policy documents related to inclusion of minority and marginalized people. Results from the mapping process within the consortium were blended with the identified resources to develop this common theoretical framework. This framework is based on scientific literature, policy documents and consensus meetings among panel members. The development of a common framework was functional to ensure a shared understanding of the justice concept and how it applies within the context of the GGR project (Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022).

Putting GID on the agenda: challenges met

Once a common understanding of GID and the related challenges within the context of GGR was achieved, decisions were made on how to operationalize the framework in order to have a real-life impact. Several approaches were suggested, however the GID panel faced financial and structural limitations that restricted its actions.

Operationalizing the GID framework: development of a GID-checklist

As a result of consensus meetings, and taking in to account the aforementioned restrictions, a GID-checklist was developed in order to operationalize and test the applicability of the framework. Checklists are common tools to guide researchers and practitioners when completing and reporting tasks (Winters et al., Reference Winters, Gurses, Lehmann, Sexton, Rampersad and Pronovost2009) in several fields – for example, Raman et al. (Reference Raman, Leveson, Samost, Dobrilovic, Oldham, Dekker and Finkelstein2016). These tools have the potential to improve safety and quality while reducing costs (Winters et al., Reference Winters, Gurses, Lehmann, Sexton, Rampersad and Pronovost2009), ensure all items relevant to the research task are addressed, and increase transparency (Busetto et al., Reference Busetto, Wick and Gumbinger2020). The GGR approach understands the checklist as a tool for researchers and practitioners to apply when developing their tasks to ensure that gender, inclusion and diversity have thoroughly been taken into consideration.

The initial checklist was tested through a pilot workshop with NbS experts in November 2022 during a GGR consortium meeting in Barcelona. Next, based on the data obtained from the pilot workshop, practical recommendations for implementation of each item were added to the checklist during four consensus meetings with the GID panel. To further refine the checklist a feedback workshop targeting transdisciplinary NbS experts was organized in February 2023 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. In person workshop with NbS experts organized in Maynooth, Ireland (February 2023).

Gender, inclusion and diversity framework

Conceptually NbS differ from other urban greening practices such as ecological infrastructure or ecosystem services because addressing social goals are considered a key aspect instead of concomitant as Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez (Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022) pointed out. However, NbS too often rely heavily on a trickle-down perspective that results in minimal benefits for those most vulnerable and can even exacerbate inequalities for disenfranchized communities (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Lamarca, Connolly and Anguelovski2017). Therefore, critical scholars have raised concerns around the distribution of these social co-benefits (Anguelovski et al., Reference Anguelovski, Connolly, Masip and Pearsall2018; Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). When applying strategies towards climate change mitigation, such as NbS, it is important to understand the dimensions of normativity and justice, beyond pure scientific, techno-managerial, or financial issues (Gardiner, Reference Gardiner2011; Shue, Reference Shue2014). Climate change is interlinked with ethics and equity because it impacts people differently, unevenly, and disproportionately (Shue, Reference Shue2014; Gaillard et al., Reference Gaillard, Gorman-Murray and Fordham2017; Sultana, Reference Sultana2022). Social inequalities tend to co-exist with harmful environmental conditions and disproportional suffering from possible effects of climate change, resulting in greater subsequent inequality and a limited ability to cope and recover (Islam and Winkel, Reference Islam and Winkel2017; Barboza et al., Reference Barboza, Montana, Cirach, Iungman, Khomenko, Gallagher, Thondoo, Mueller, Keune and MacIntyre2023). Hence, a climate justice approach is essential because such an approach focuses on who benefits, who is harmed, in what ways privileges and losses are conferred, as well as where and why. Thus, it is also essential to recognize that climate change involves a common but differentiated responsibility. The aforementioned understanding necessitates justice to be a central entry point for this GID framework.

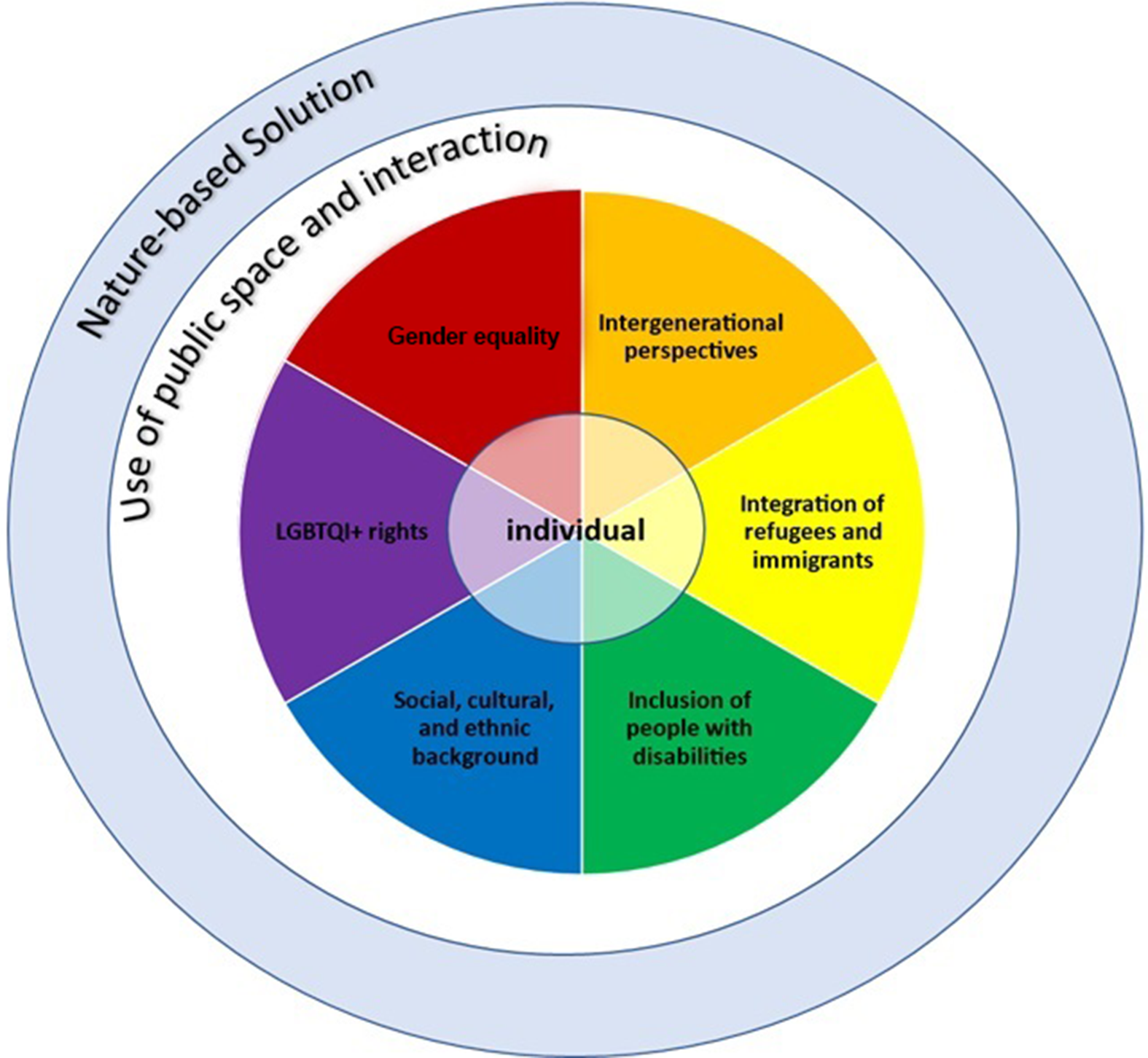

For justice to be central in NbS, it must be integrated intentionally in the design and implementation process. Furthermore, NbS development must be sensitive to the community in which it is enacted, forming explicit pathways to justice that counter and rectify implicit injustice (Sultana, Reference Sultana2022). Therefore, within the context of this framework, six domains including disadvantaged populations within a European context have been identified by the GID panel, that require specific attention: (1) gender equality; (2) LGBTQI + rights; (3) social, cultural and ethnic background; (4) people with disabilities; (5) integration of refugees and immigrants; (6) intergenerational perspectives. Although these domains are presented as distinct categories here, individuals can be affected by more than one domain or can be confronted with more than one justice issue (e.g., immigrant woman identifying as lesbian). Hence, intersectionality is a key component of the framework (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Gender, Inclusion and Diversity framework as developed within the GoGreenRoutes project applies a climate justice perspective while addressing how the nexus of gender equality, age, LGBTQI + rights, social; cultural and ethnic background, inclusion of people with disabilities and, displaced populations and immigrants impacts the use of public spaces and interactions and considers the possible consequences for participating in participatory processes towards NbS development and Implementation.

As mentioned above, the use and planning of public spaces is inherently political because the use of and the interactions in public spheres are resulting from an underlying set of social practices and social structures including the power dynamics at the core of social injustices (Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). This theoretical framework developed in the context of GGR focusses on ways in which diverse minority and marginalized groups might be underrepresented in participatory processes as a result of a compromised use of public space – for example non-binary individuals might disguise their non-binary identity when navigating through public spheres and/or limit their interactions in the public sphere due to local contextual factors such as transphobic violence or general hostile environments. Below, the five domains identified in this theoretical framework are addressed. A rationale on how minority or marginalized status linked to these domains might negatively impact the use of public spheres and the participation in participatory processes by individuals affiliated to these domains, is provided.

NbS and gender equality

Organizations such as the International Institute for Sustainable Development assert that NbS are powerful tools for women’s empowerment towards climate adaptation (Women Deliver. 2021). Women experience the urban environment differently from men, with variations in daily routines and roles. Furthermore, feelings of safety influence green space usage (Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Conigliaro and Salbitano2021; UN Habitat, 2008). It is important that NbS projects curate intentional gender equity and not simply gender diverse participation, this in order to be gender transformative with the ultimate aim to change the underlying root causes of gender inequalities (IGWG, 2017). This requires women and gender diverse individuals to be engaged in decision-making roles to account for gender specific outcomes (Bremer et al., Reference Bremer, Keeler, Pascua, Walker and Sterling2021). Spontaneous empowerment will not occur, but rather empowerment within NbS can be cultivated utilizing protocols and tools that are sensitive to gendered perspectives from the outset. This potentially offers a strategy to track and measure the project outputs and gender representation over time, working towards targeted metrics.

NbS and LGBTQI+ rights

Individuals identifying as LGBTQI+ face significant legal and societal challenges in EU countries and around the globe, often including criminalization and medicalization. As such, LGBTQI+ individuals are in marginalized positions from a social, legal and physical perspective (Whitley and Bowers, Reference Whitley and Bowers2023). Moreover, structural inequalities like poverty and stigma (e.g., transphobia) are also prevalent and might limit their active participation in participatory processes (Moazen-Zadeh et al., Reference Moazen-Zadeh, Karamouzian, Kia, Salway, Ferlatte and Knight2019). Furthermore, climate change is expected to exacerbate the inequalities faced by LGBTQI+ people (Dietz and Whitley, Reference Dietz and Whitley2018; Cappelli et al., Reference Cappelli, Costantini and Consoli2021). Nonetheless, LGBTQI+ people have largely been excluded from conversations and policy responses with climate mitigating potentials such as NbS, reflecting heteronormative and cisnormative practices (Gaillard et al., Reference Gaillard, Gorman-Murray and Fordham2017). Moreover, the United Nations expresses the need to advance and prioritize LGBTQI+ health in all policies and research strategies (United Nations. 2015).

NbS and social, cultural and ethnic background

Apart from the fact that investments in greening initiatives such as NbS often overlaps with wealthy areas of the cities (Dai, Reference Dai2011; Wen et al., Reference Wen, Zhang, Harris, Holt and Croft2013; Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Conigliaro and Salbitano2021), it is important to acknowledge that even if NbS are planned in areas where people occupying lower social positions (also) reside, there are two additional risks: a) participation might be skewed in favor of people occupying higher social positions (Dalton, Reference Dalton2017), and b) a process of gentrification might occur. Green gentrification is a complex issue that can lead to displacement and alienation of socio-economic vulnerable residents (Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Conigliaro and Salbitano2021; Sax et al., Reference Sax, Nesbitt and Quinton2022). Participatory processes should integrate different actors from the public sector in order to minimize the risk of gentrification. Moreover, people that occupy higher social positions often possess what Bourdieu has called “symbolic capital”, that is, a form of capital that is not recognized as such. For example, prestige can operate as symbolic capital because it means nothing in itself, but rather depends on crowds believing that certain people hold this attribute (Webb et al., Reference Webb, Schirato and Danaher2002). We argue that in the context of participatory processes this could result in specific groups dominating the narrative and, ultimately, the NbS reflecting the needs of those groups. When considering cultural and ethnic backgrounds the fear of experiencing racism and feelings of unsafety can lead to the exclusion of some groups (Borelli et al., Reference Borelli, Conigliaro and Salbitano2021). Moreover, diverse spaces need to be provided to meet the needs of diverse communities.

NbS and people with disabilities

People with disabilities are negatively impacted by a range of factors relating to attitudes and the environment that affect their access to NbS. This includes barriers relating to a lack of awareness surrounding persons with disabilities, access to participating and leading NbS, and discriminatory attitudes or lack of consideration for this group (Martin and Hossain, Reference Martin and Hossain2022). Additional barriers are also related to inaccessibility of infrastructure, information, equipment and training (Martin and Hossain, Reference Martin and Hossain2022). Also, at an institutional level, lack of consideration for including persons with disabilities in the creation of programs negatively impacts people with disabilities’ access to NbS. In addition, lack of thought toward their unique needs, through insufficient participation as well as discriminatory policies negatively impact this population’s access to NbS (Martin and Hossain, Reference Martin and Hossain2022). The four main factors which compound these barriers are 1) lack of inclusion of the capabilities and needs of this population especially within laws, mandates and funding, 2) lack of data on persons with disabilities especially relating to NbS and climate change, 3) lack of meaningful consultation and engagement with persons with disabilities (NIRAS, 2021; Jodoin et al., Reference Jodoin, Lofts, Bowie-Edwards, Leblanc and Rourke2022; Martin and Hossain, Reference Martin and Hossain2022), 4) lack of additional funding and resources to increase outreach, activities and accommodations for disability inclusion (Grant, Reference Grant2022).

NbS and integration of refugees and immigrants

Immigrants and refugees in Europe generally live in densely populated areas with less access to green spaces (Sekulova and Anguelovski, Reference Sekulova and Anguelovski2017). Research shows that immigrants living in these urban areas have less access to green areas and parks in comparison to nonimmigrants (Kabisch et al., Reference Kabisch, van den Bosch and Lafortezza2017). These limitations can have significant long term impacts on immigrant communities through health, loss of culture and social integration to their new community (Gentin et al., Reference Gentin, Pitkänen, Chondromatidou, Præstholm, Dolling and Palsdottir2019). Integration policies on an European level emphasize the health of immigrant communities and suggest that NbS can help bridge the gap on these impacts (Gentin et al., Reference Gentin, Pitkänen, Chondromatidou, Præstholm, Dolling and Palsdottir2019).

NbS and intergenerational perspectives

Youth

Involving youth in the decision-making process of developing NbS is important as this builds a sense of empowerment to make changes and decisions in their communities. This has been shown to be beneficial in combating external pressures of climate change through involvement in NbS and fighting for the future they want (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, van Ham, Reilly and Hopkins2019). Young people see the world from their own unique perspective and have their own wants and needs related to play (Dushkova and Haase, Reference Dushkova and Haase2020). NbS can have a positive impact on the current and future health of this population. It has been shown that children are more vulnerable to the health impacts of living in urban environments, especially during their developmental years (Kabisch et al., Reference Kabisch, van den Bosch and Lafortezza2017). This because activity within green spaces improves the mental health and social well-being of young people during challenging times of their lives (MacKinnon et al., Reference MacKinnon, van Ham, Reilly and Hopkins2019).

Elderly

The elderly population interacts with NbS and environments differently than others. It is shown that they are more sensitive to heat/cold, subject to loss of cognitive functions and reflexes, higher rate of urinary incontinence, cardiovascular and respiratory issues, as well as feelings of insecurity in public places (Higueras et al., Reference Higueras, Román and Fariña2021). Thus, it is important to offer the aging population a seat at the table to share their experiences and give them a sense of ownership over their community. Urban green space has been proven to improve mood, reduce stress, prevent cardiovascular disease, and decrease risk factors associated with air pollution or urban heat (Kabisch et al., Reference Kabisch, van den Bosch and Lafortezza2017). Those are all important factors to an aging population. Also, green space provides an opportunity for physical activity and social interaction both of which can have a positive impact on overall health and well-being (Kabisch et al., Reference Kabisch, van den Bosch and Lafortezza2017).This is particularly important for isolated aging populations. Thus, it is important to ensure that these groups have an opportunity for their voices to be heard and needs to be met, to provide them with equal opportunities and access to NbS.

Checklist

The checklist was co-created by transdisciplinary experts keeping in mind the concrete moments of interaction between municipalities and citizens for co-designing and co-implementing NbS. It includes three main aspects namely, (1) when preparing for activities engaging with the public, (2) when communicating with the public and, (3) when reflecting on engagement with the public. These are interrelated parts given that there should be proactive communication in advance of public invitation to engage in activities as well as post activity communication and reflection. Therefore, it is important that these parts are seen as interlinked and should be considered in relation to interactions with the public by the municipalities. The aim of the checklist is to ensure the fundamental elements for inclusivity are taken into account when communicating with the public or engaging them in any activities. The checklist is published as supplementary material.

Recommendations for further application of the framework

This framework provides some theoretical understanding of how the participation of diverse minority and marginalized groups might be compromised. However, it often remains unclear how groups experience different barriers and how far the full width of this impact extends. It is therefore essential to investigate the lived experiences of these groups in order to gain insights into how historically rooted injustices can be eradicated and rectified. The authors acknowledge that the framework was created considering the dynamics of European urban settlements and also suggest that further research is needed to explore how the proposed framework could be adapted for further applications in more rural environments and other regions.

Moreover, little is known on the level of inclusion NbS achieve during both planning and implementation processes as Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez (Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022) has previously stated. This framework demonstrates in a theoretical sense the necessity of assessing the level of inclusion throughout the entire NbS lifecycle as there are empirical arguments to contest that NbS will, by default, deliver on equity and justice goals (Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). In addition, there are normative arguments to urge the NbS community to make explicit who was involved throughout the NbS lifecycle and at which level of participation (Biermann and Kalfagianni, Reference Biermann and Kalfagianni2020; Cousins, Reference Cousins2021; Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez, Reference Wijsman and Berbes-Blazquez2022). The checklist as developed in the context of GGR can aid in making these factors explicit, however further research should seek to implement and refine this checklist in different contexts, as well as thoroughly evaluate its impact on the participation of marginalized and minority people.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/one.2023.14.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratefulness to all GoGreenRoutes consortium partners who participated in the Barcelona pilot workshop in November 2022 and/or the Maynooth feedback workshop in February 2023.

Author contributions

BD coordinated the development of the framework and wrote the original draft of the manuscript. EPB and HK critically reviewed the manuscript and finetuned the framework. EVR coordinated the panel meetings. KP, EMC, AMB, SU, KR, MJFOF, AD, and JG contributed to the framework based on their expertise. All authors contributed to the development of the checklist.

Financial support

This work was supported by GoGreenRoutes through the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program under grant agreement No 869764.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest of any kind.

Comments

No accompanying comment.