Introduction

Cognition encompasses discrete yet overlapping processes including, but not limited to, executive functions (eg, planning, behavioral initiation and monitoring, and impulse control), attention, memory, and processing speed.Reference McIntyre, Cha and Soczynska 1 Although bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are distinct diagnostic entities based on their clinical presentations, neurocognitive impairment is recognized as a core feature of both disordersReference Bortolato, Miskowiak, Kohler, Vieta and Carvalho 2 ; approximately 40% to 60% of patients with bipolar disorder and up to 75% of patients with schizophrenia experience cognitive deficits.Reference Sole, Jimenez and Torrent 3 , Reference Raffard, Gely-Nargeot, Capdevielle, Bayard and Boulenger 4 While some studies have found comparable degrees of cognitive impairment in patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia,Reference Altshuler, Ventura, van Gorp, Green, Theberge and Mintz 5 – Reference Schretlen, Cascella and Meyer 10 others indicate that patients with schizophrenia have more severe and/or pervasive impairment.Reference Lewandowski, Cohen and Ongur 11 – Reference Vohringer, Barroilhet and Amerio 13 In both disorders, however, cognitive deficits are associated with worse outcomes and diminished quality of life, including more hospitalizations, longer duration of illness, positive and negative psychotic symptoms, nonremission status, and lower psychosocial functioning.Reference Kuswanto, Chin and Sum 14 , Reference Gkintoni, Pallis, Bitsios and Giakoumaki 15 As no therapeutic agent is currently approved to treat cognitive impairment in patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, cognitive deficits are widely recognized as an unmet medical need and a novel treatment target in these illnesses.Reference Kuswanto, Chin and Sum 14 , Reference Martinez-Aran and Vieta 16

While dopamine dysregulation has been implicated in the pathophysiology of both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia,Reference Ashok, Marques and Jauhar 17 , Reference Howes, McCutcheon, Owen and Murray 18 evidence from animal and human research suggests that the dopaminergic system also plays a role in cognitive function.Reference Backman, Nyberg, Lindenberger, Li and Farde 19 – Reference Nakajima, Gerretsen and Takeuchi 21 Specifically, dopamine D3 receptors appear to be associated with cognitive functioning in healthy individuals and in those with neuropsychiatric disorders,Reference Nakajima, Gerretsen and Takeuchi 21 , Reference Stahl 22 with evidence that domains of memory, attention, learning, processing speed, social recognition, and executive function are potentially enhanced by D3 receptor blockade and impaired by D3 receptor agonism.Reference Nakajima, Gerretsen and Takeuchi 21 As such, cognitive performance in individuals with a neuropsychiatric disorder may be improved by D3 receptor blockade,Reference Nakajima, Gerretsen and Takeuchi 21 suggesting that a dopamine antagonist/partial-agonist agent that more potently targets D3 receptors than D2 receptors could have potentially beneficial effects on cognition.Reference Kiss, Horvath and Nemethy 23 It is important to note, however, that cognition is a complex concept, and although clinical observations support the role of dopamine D3 in cognitive function in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder, cognitive deficits may have a heterogenous origin and other factors, including receptors other than dopamine D3, could be involved.

Cariprazine is a dopamine D3-preferring D3/D2 receptor partial agonist and serotonin 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist that is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat adults with depressive (1.5-3 mg/d) or manic/mixed (3-6 mg/d) episodes associated with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia (1.5-6 mg/d). The pharmacology of cariprazine is unique among dopamine modulating agents, demonstrating almost 10-fold greater affinity for D3 than D2 receptors in vitro,Reference Kiss, Horvath and Nemethy 23 as well as high and balanced in vivo occupancy of D3 and D2 receptors.Reference Girgis, Slifstein and D’Souza 24 In support of a potential advantage for treating cognitive symptoms, cariprazine has demonstrated efficacy in animal models of cognitive impairment,Reference Neill, Grayson, Kiss, Gyertyan, Ferguson and Adham 25 , Reference Zimnisky, Chang, Gyertyan, Kiss, Adham and Schmauss 26 with evidence that procognitive effects were mediated by the dopamine D3 receptor.Reference Zimnisky, Chang, Gyertyan, Kiss, Adham and Schmauss 26 The efficacy of cariprazine was established in randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pivotal phase 2/3 clinical trials for the treatment of depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder (3 trials),Reference Durgam, Earley and Lipschitz 27 – Reference Earley, Burgess and Khan 29 acute manic/mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorderReference Calabrese, Keck and Starace 30 – Reference Sachs, Greenberg and Starace 32 (3 trials), and schizophrenia (3 trials)Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 – Reference Kane, Zukin and Wang 35 ; cariprazine has also demonstrated broad efficacy across individual symptoms and symptom domains in each approved indication.Reference Fleischhacker, Galderisi and Laszlovszky 36 – Reference Yatham, Vieta, McIntyre, Jain, Patel and Earley 39

To investigate the effects of cariprazine on cognitive symptoms across the indications of bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia, we conducted post hoc analyses of data relevant to cognitive symptom change. As the constituent studies were not prospectively designed to assess cognition, these post hoc analyses were exploratory and they were based on available measures in each indication.

In bipolar I disorder, most of the presented analyses were based on pooled data from the pivotal studies in bipolar depression and mania; an additional post hoc analysis that was based on a cognitive measure collected in one bipolar depression study is also presented. Pooled cognition analyses in schizophrenia have been previously reportedReference Fleischhacker, Galderisi and Laszlovszky 36 , Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 37 ; results from a computerized battery of cognitive tests that was conducted in one pivotal study in patients with schizophrenia (RGH-MD-04) are reported here as a supportive analysis.

Methods

Study designs and participants

Post hoc analyses were conducted on data from phase 2/3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter clinical trials of cariprazine in bipolar I depression, bipolar I mania, and schizophrenia. Patients in the constituent studies gave informed written consent; study protocols were approved by institutional review board (U.S. centers) or ethics committee/government agency (non-U.S. centers).

Detailed methods of the bipolar I depression studies,Reference Durgam, Earley and Lipschitz 27 – Reference Earley, Burgess and Khan 29 the bipolar mania studies,Reference Calabrese, Keck and Starace 30 – Reference Sachs, Greenberg and Starace 32 and RGH-MD-04 in schizophreniaReference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 have been previously published. Briefly, each study had a washout period of up to 1 week, followed by a 6-week (bipolar depression studies and schizophrenia study) or 3-week (bipolar mania studies) double-blind evaluation period, and a 2-week safety follow-up. Adult patients (bipolar I disorder: 18-65 years; RGH-MD-04 [schizophrenia]: 18-60 years) met Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR or DSM-5) 40 , 41 criteria for bipolar I disorder (acute manic/mixed or depressive episode) or schizophrenia depending on the disorder under investigation; patients with bipolar I mania and schizophrenia were hospitalized during screening and for at least the first 2 weeks of treatment. Post hoc analyses were conducted in the respective intent-to-treat populations modified by pooling and the application of subgroup criteria (mITT).

Participants in the constituent studies met inclusion and exclusion criteria that are typical of criteria used in clinical studies of bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia. In the bipolar depression studies, participants were required to have a Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD17) total score ≥20 and an item 1 score ≥2,Reference Hamilton 42 and a Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S) score ≥4.Reference Guy 43 In the bipolar I mania studies, participants were required to have a Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) total score ≥20 and a score ≥4 on at least 2 of 4 YMRS items (irritability, speech, content, and disruptive/aggressive behavior)Reference Young, Biggs, Ziegler and Meyer 44 and a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) total score <18.Reference Montgomery and Asberg 45 In the RGH-MD-04 schizophrenia study, participants were required to have a Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total score ≥80 and ≤120 and a score ≥4 on at least 2 of 4 PANSS items (Delusions, Hallucinatory Behavior, Conceptual Disorganization, and Suspiciousness/Persecution Items),Reference Kay, Fiszbein and Opler 46 and a CGI-S score ≥4. Key exclusion criteria in each study included a DSM axis I diagnosis other than the disorder under investigation, alcohol- or substance-related disorders within a specified timeframe (3 months for bipolar mania and schizophrenia and 6 months for bipolar depression), risk for suicide, and previous nonresponse to approved treatment or treatment resistance.

Bipolar I depression

To analyze cognitive symptoms in adult patients with bipolar I disorder and a current depressive episode, 6-week data were pooled from all 3 pivotal cariprazine studies.Reference Durgam, Earley and Lipschitz 27 – Reference Earley, Burgess and Khan 29 In RGH-MD-53 (NCT02670538) and RGH-MD-54 (NCT02670551), patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive placebo, or cariprazine 1.5 or 3 mg/d; in RGH-MD-56 (NCT01396447), patients were randomized (1:1:1:1) to receive placebo or cariprazine 0.75, 1.5, or 3 mg/d. The double-blind period was 6 weeks in RGH-MD-53 and -54, and 8 weeks in RGH-MD-56; the primary efficacy endpoint was week 6 in all studies. Cariprazine 0.75 mg/d was not included in these analyses since it is below the recommended dose for bipolar depression. The primary efficacy outcome in all 3 studies was change from baseline to week 6 in MADRS total score. The Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST),Reference Rosa, Sanchez-Moreno and Martinez-Aran 47 a 24-item clinician-rated scale that assesses 6 areas of functioning in patients with bipolar disorder (ie, autonomy, occupational functioning, cognitive functioning, financial issues, interpersonal relationships, and leisure time), was administered as an additional efficacy assessment in RGH-MD-56 only; changes in FAST outcomes were assessed from baseline to end of the 8-week double-blind period.

Post hoc analyses evaluated changes from baseline to week 6 in MADRS Concentration Item (item 6) score and MADRS total score in the overall mITT population (all patients who received study treatment and had at least 1 postbaseline efficacy assessment) and in 2 patient subgroups with greater levels of cognitive symptoms (at least mild cognitive symptoms = item 6 score ≥3; at least moderate cognitive symptoms = item 6 score ≥4). Scores on item 6 range from 0 (no difficulty in concentration) to 6 (unable to read or converse without great initiative). In RGH-MD-56 only, cognitive functioning was also evaluated by changes from baseline to week 8 in FAST total score, FAST Cognitive Functioning subscale score, and FAST Cognitive item scores in the mITT population and in a patient subset with baseline cognitive symptoms defined as a FAST Cognitive Functioning subscale score ≥2 on 2 or more of 5 cognitive items. The FAST Cognitive Functioning subscale is scored as the sum of 5 items (Ability to Concentrate on a Book/Film, Make Mental Calculations, Solve a Problem Adequately, Remember Newly Learned Names, and Learn New Information); scores range from 0 (no difficulty) to 3 (severe difficulty) for each item, with higher scores indicating greater impairment.

Bipolar I mania

To analyze cognitive symptoms in adult patients with manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder, data were pooled from all 3 pivotal 3-week cariprazine studies.Reference Calabrese, Keck and Starace 30 – Reference Sachs, Greenberg and Starace 32 In RGH-MD-31 (NCT00488618) and RGH-MD-32 (NCT01058096), patients were randomized (1:1) to receive placebo or flexible-dose cariprazine 3 to 12 mg/d; in RGH-MD-33 (NCT01058668), patients were randomized (1:1:1) to receive placebo or fixed/flexible dose cariprazine 3 to 6 mg/d or 6 to 12 mg/d. The primary efficacy outcome in each bipolar mania study was change from baseline to week 3 in YMRS total score; the PANSS was also administered as an additional efficacy outcome in each study.

Post hoc analyses evaluated changes from baseline to day 21 in PANSS Cognitive subscale score,Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 , Reference Meltzer, Cucchiaro and Silva 48 PANSS Cognitive subscale individual item scores, and YMRS total score. The items of the PANSS Cognitive subscale are P2 (Conceptual Disorganization), N5 (Difficulty in Abstract Thinking), N7 (Stereotyped Thinking), G10 (Disorientation), and G11 (Poor Attention), with scores ranging from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme). Outcomes were assessed in the mITT population and in a subset of patients with greater cognitive symptoms, defined as PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15 (representing an average score of 3 [mild severity] on each item of the 5-item subscale). Changes from baseline were also evaluated in a less restrictive subset defined as patients with a baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score greater than or equal to the median (median = 11).

Schizophrenia

Cognitive symptom outcomes from all 3 pivotal 6-week cariprazine studies in adult patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia and from a 26-week study in patients with schizophrenia and predominant negative symptoms have been previously analyzed and reported.Reference Fleischhacker, Galderisi and Laszlovszky 36 , Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 37 To objectively evaluate the effect of cariprazine on cognitive symptoms in schizophrenia, performance-based outcomes from the Cognitive Drug Research (CDR) system attention battery,Reference Simpson, Surmon, Wesnes and Wilcock 49 which was an additional efficacy parameter in pivotal study RGH-MD-04 (NCT01104766),Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 were investigated. The CDR system attention battery consists of 3 brief and highly sensitive tests (simple reaction time, digit vigilance, and choice reaction time) organized into factors; power of attention (PoA) and continuity of attention (CoA) factors were reported. In RGH-MD-04, patients with a current psychotic episode <2 weeks in duration were randomized (1:1:1:1) to receive placebo, cariprazine 3 mg/d, cariprazine 6 mg/d, or aripiprazole 10 mg/d (included for assay sensitivity).

Statistical analyses

Change in MADRS, PANSS, and FAST assessments were analyzed using a mixed-effects model for repeated measures with an unstructured covariance matrix including study, baseline score, treatment, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction, and baseline-by-visit interaction as covariates. All statistical tests were 2-sided at the 5% significance level; P values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons. Median changes and P values for CDR system attention battery outcomes were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test based on a last observation carried forward approach.

Results

Bipolar depression

Patient disposition

There was a total of 1383 patients in the pooled mITT bipolar depression population (Table 1). At baseline, 88.4% of patients had at least mild cognitive symptoms (MADRS item 6 score ≥3) and 66.0% had at least moderate cognitive symptoms (MADRS item 6 score ≥4); baseline MADRS item 6 and total scores were similar in placebo- and cariprazine-treated groups. In RGH-MD-56, 393 patients had baseline and postbaseline FAST scores and were included in the mITT population. Mean baseline FAST total score in the mITT population was 38.8, indicating a population with moderate-to-severe functional impairment.Reference Bonnin, Martinez-Aran and Reinares 50 A total of 75.8% of patients had baseline cognitive symptoms (FAST Cognitive score of ≥2 on at least 2 of the 5 items; Table 1).

Table 1. Bipolar Depression: Subsets with Greater Cognitive Symptoms at Baseline

Abbreviations: FAST, Functional Assessment Short Test; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale; mITT, modified intent to treat.

a mITT is defined as all randomized patients who took at least 1 dose of double-blind study drug and had at least 1 postbaseline efficacy score.

Changes in cognitive and depressive symptoms: MADRS item 6 and total score

In the pooled mITT population, least squares (LS) mean change from baseline to week 6 in MADRS concentration item (item 6) was −1.2 for placebo, −1.6 for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d, and −1.4 for cariprazine 3 mg/d; differences vs placebo were statistically significant for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d (P < .0001) and 3 mg/d (P = .0365). The difference in mean change from baseline in MADRS item 6 was statistically significant for cariprazine 1.5 and 3 mg/d vs placebo in patients with at least mild cognitive symptoms (item 6 score ≥3) and at least moderate cognitive symptoms (item 6 score ≥4; Figure 1A). In patients with at least mild cognitive symptoms, the LS mean change from baseline to week 6 was −1.3 for placebo, −1.8 for 1.5 mg/d (P < .0001), and −1.5 for 3 mg/d (P = .0292); in patients with at least moderate cognitive symptoms, the LS mean change was −1.5 for placebo, −1.9 for 1.5 mg/d (P < .0001), and −1.7 for 3 mg/d (P = .0366).

Figure 1. MADRS change from baseline to week 6 in patients with bipolar depression and cognitive symptoms. Differences in change from baseline on the (A) MADRS Concentration item and (B) MADRS total score were statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 1.5 and 3 mg/d vs placebo for patients in higher and lower cognitive symptom subgroups.

*P < .05 and ***P < .001 vs placebo. Abbreviations: LS, least squares; MADRS, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale.

The difference in mean change from baseline in MADRS total score (depressive symptoms) was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine vs placebo for patients with at least mild cognitive symptoms and at least moderate cognitive symptoms (Figure 1B). LS mean change in MADRS total score was −12.0 for placebo, −15.1 for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d (P < .0001), and −14.7 for 3 mg/d (P = .0001) in patients with at least mild cognitive symptoms and −12.3 for placebo, −15.6 for 1.5 mg/d (P < .0001), and −15.2 for 3 mg/d (P < .0006) in patients with at least moderate cognitive symptoms.

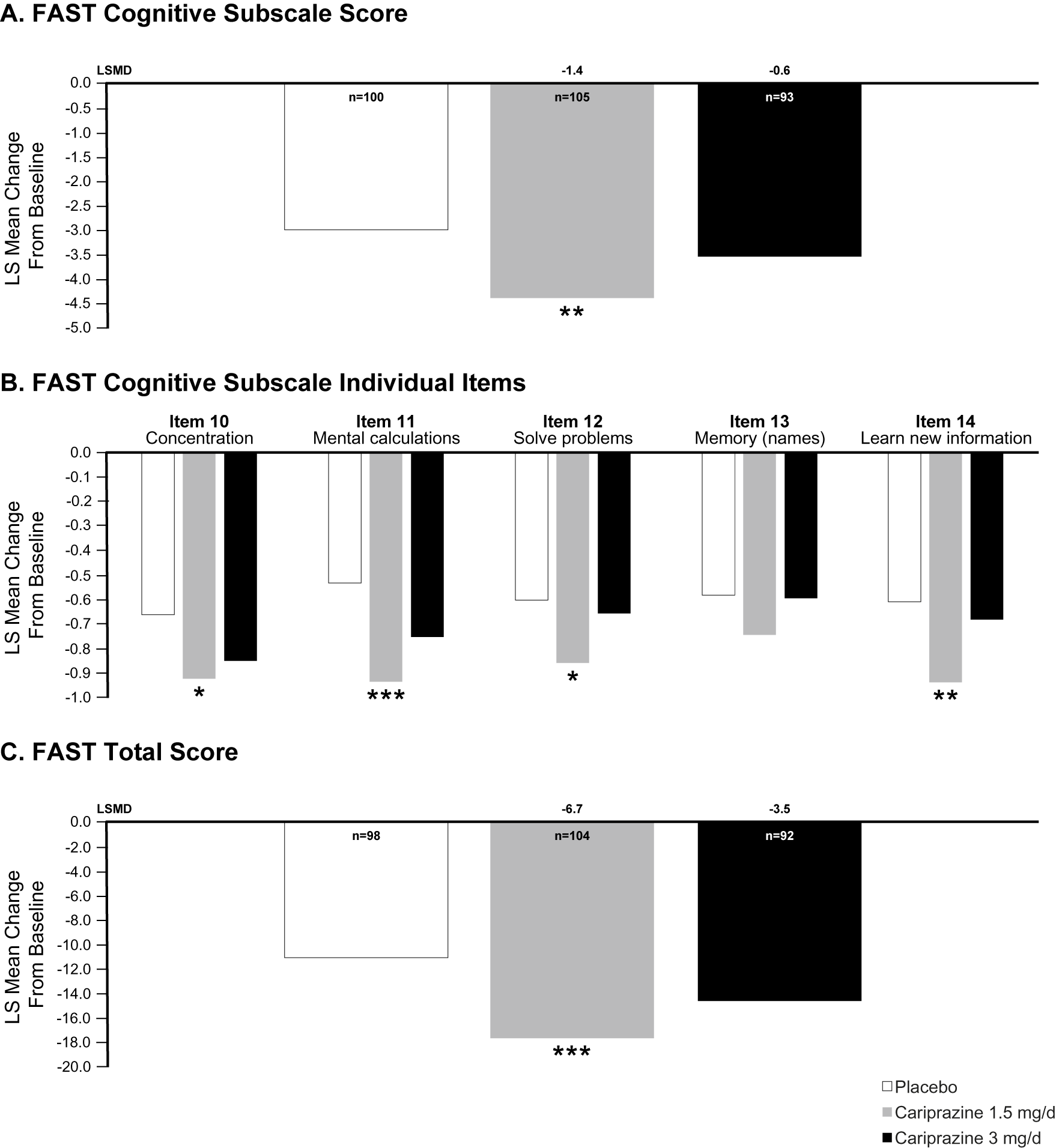

Change in functioning: FAST Cognitive subscale score, item scores, and total score

In the overall ITT population, the difference in change from baseline to week 8 in FAST Cognitive subscale score was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d vs placebo (LSMD = −1.2; P = .0035); the difference for cariprazine 3 mg/d vs placebo was not statistically significant (LSMD = −0.5). In patients with baseline cognitive symptoms (scores ≥2 on at least 2 of 5 FAST Cognitive subscale items), the difference in change from baseline in FAST Cognitive subscale score was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d vs placebo (LSMD = −1.4; P = .0039); the difference for cariprazine 3 mg/d vs placebo was not statistically significant (LSMD = −0.6; Figure 2A). Also of note, changes from baseline were significantly different in favor of cariprazine 1.5 mg/d vs placebo on 4 of 5 individual symptom items included in the FAST Cognitive subscale (ie, Concentration, Mental Calculations, Solve Problems, and Learn New Information); no statistically significant differences vs placebo were seen for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d on the “Memory For a New Name” item or for cariprazine 3 mg/d on any item (Figure 2B). In the subset of patients with baseline cognitive symptoms, the difference in change from baseline in FAST total score was also statistically significant for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d (LSMD = −6.7; P = .0009) vs placebo, suggesting overall functional improvement in this group; cariprazine 3 mg/d was not significantly different than placebo (LSMD = −3.5; Figure 2C).

Figure 2. FAST change from baseline to week 8 in patients with bipolar depression and cognitive symptoms (FAST Cognitive subscale item score ≥2 on at least 2 of 5 items). (A) The difference in change from baseline on the FAST Cognitive subscale was significantly different for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d vs placebo. (B) Changes from baseline in FAST individual item scores were significantly different for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d vs placebo on all items except Memory. (C) Change from baseline in FAST total score was significantly different than placebo for cariprazine 1.5 mg/d.

*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 vs placebo. Abbreviations: FAST, Functional Assessment Short Test; LS, least squares.

Bipolar mania

Patient disposition

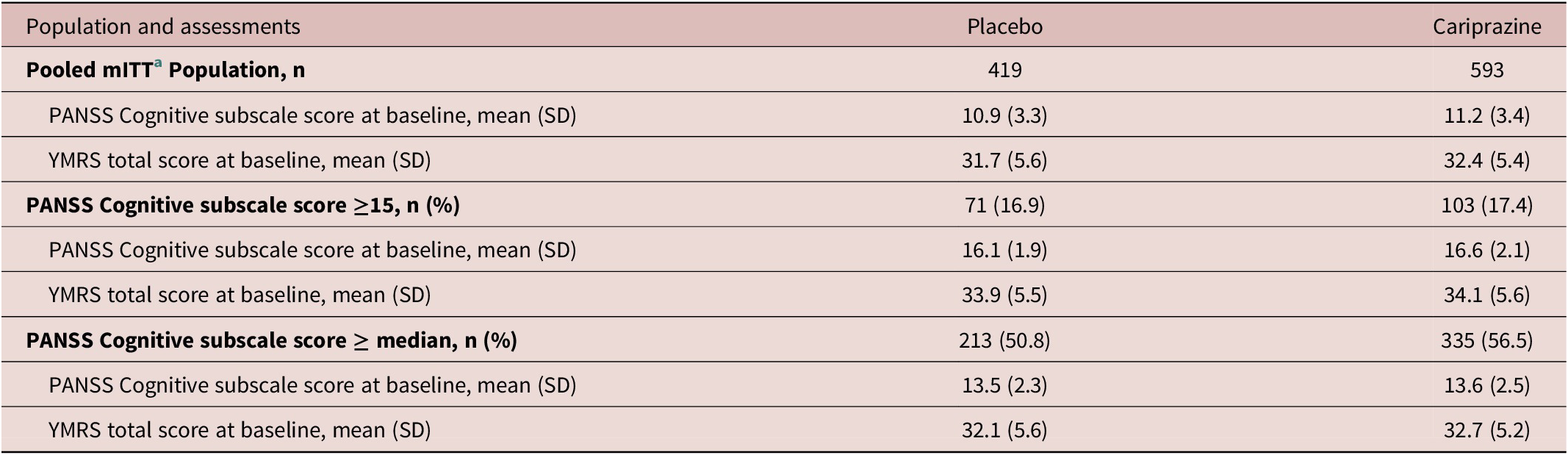

There were a total of 1012 patients in the pooled mITT bipolar mania population (Table 2). Baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale scores and YMRS total scores were similar in the cariprazine and placebo groups in the mITT population. Similar PANSS Cognitive subscale scores and YMRS total scores for cariprazine and placebo were also noted at baseline in the subset with PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15 and in the subset with a baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score at or above the median (Table 2). More than half of all patients had a baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score at or above the median (11), whereas 17.2% of patients had PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15 (Table 2).

Table 2. Bipolar Mania: Baseline Scores Overall and in Subsets with Greater Cognitive Symptoms at Baseline

Note: Median PANSS cognitive subscale score = 11.

Abbreviations: mITT, modified intent to treat; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

a mITT is defined as all randomized patients who took at least 1 dose of double-blind study drug and had at least 1 postbaseline Cognitive subscale PANSS assessment.

Change in cognitive symptoms: PANSS Cognitive subscale score and item scores

In the pooled mITT population, mean change from baseline to day 21 in PANSS Cognitive subscale score was −2.2 for cariprazine and −1.3 for placebo, with a statistically significant LSMD in favor of cariprazine over placebo (−0.9; P < .0001). In patients with PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15, the difference in change from baseline to day 21 was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine vs placebo (P = .0002); in patients with a PANSS Cognitive subscale score above the median, a statistically significant difference in favor of cariprazine vs placebo was again noted (P < .0001; Figure 3A). In patients with a PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15, changes from baseline to day 21 were significantly different in favor of cariprazine vs placebo on all individual PANSS Cognitive subscale items except for “Disorientation” (Figure 3B). For patients with a baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score at or above the median, LSMDs were also statistically significant in favor of cariprazine on 4 of 5 items (P2: −0.4, P < .0001; N5: −0.2, P = .0127; N7: −0.1, P = .1246; G10: −0.1, P = .0392; G11: −0.3, P = .0002); unlike the subset with baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15, the difference on item N7 was not statistically significant, although the difference on item G10 was statistically significant (data not shown).

Figure 3. PANSS Cognitive subscale change from baseline to day 21 in patients with bipolar mania and cognitive symptoms. (A) The difference in change from baseline was statistically significant for cariprazine vs placebo in patients with cognitive symptoms defined as PANSS Cognitive subscales score ≥15 and greater than or equal to the median. (B) On individual subscale items, differences were statistically significant in favor of cariprazine on each item except Disorientation for patients with subscales score ≥15.

*P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .001 vs placebo. Abbreviations: LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale.

Change in mania symptoms: YMRS total score

The difference in mean change from baseline to day 21 in manic symptoms was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine vs placebo in the subset of patients with baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale score ≥15 (LSMD = −8.6; P < .0001); a smaller, but statistically significant mean difference was also noted for cariprazine vs placebo in the subset with baseline PANSS Cognitive subscale scores at or above the median (LSMD = −5.6; P < .0001; Figure 4).

Figure 4. Change from baseline in YMRS total score at day 21 in patients with bipolar mania and cognitive symptoms. The difference in change from baseline in manic symptoms was statistically significant for cariprazine vs placebo in patients with cognitive symptoms defined as PANSS Cognitive subscales score ≥15 and greater than or equal to the median.

***P < .001 vs placebo. Abbreviations: LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; YMRS, Young Mania Rating Scale.

Schizophrenia

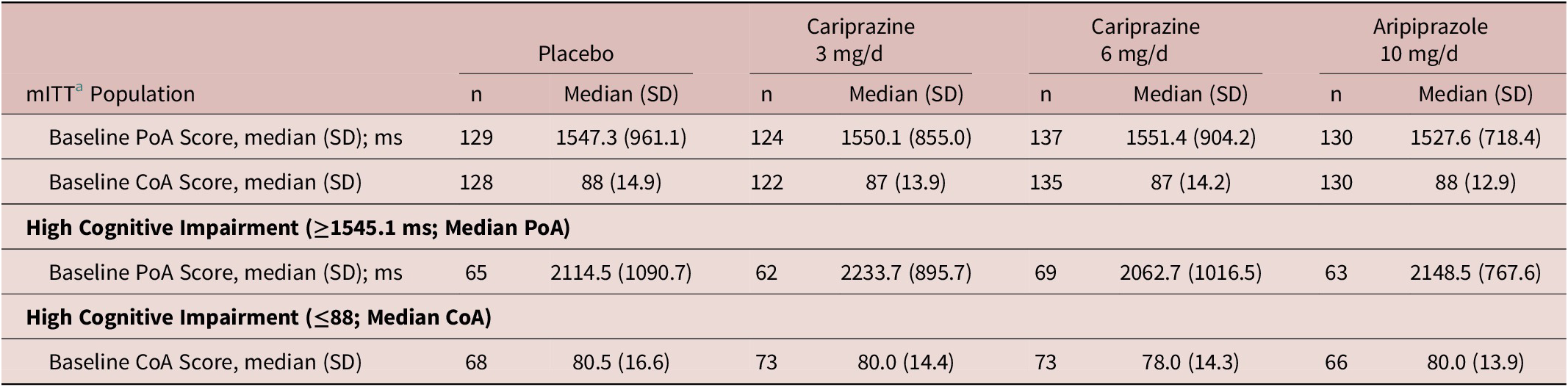

Patient disposition

A total of 520 patients were included in the mITT population of schizophrenia study RGH-MD-04 (Table 3). The high cognitive impairment subsets included patients with scores above or equal to the median PoA time (≥1545.1 ms) and below or equal to the median COA score (≤88).

Table 3. Schizophrenia: Performance-Based Measures at Baseline Overall and in Subsets with Cognitive Impairment at Baseline

Abbreviations: CoA, continuity of attention; mITT, modified intent to treat; ms, milliseconds; PoA, power of attention.

a mITT is defined as all randomized patients who took at least 1 dose of double-blind investigational product and had at least one postbaseline PoA or CoA assessment.

Changes in cognition performance measures: CDR system power of attention and continuity of attention

In the mITT population, the median (SD) change from baseline to week 6 in PoA (ms) was 27.3 (597.5) for placebo, −59 (595.1; P = .0036) for cariprazine 3 mg/d, 5.7 (781.8; P = .1272) for cariprazine 6 mg/d, and 44.2 (828.1; P = .4104) for aripiprazole 10 mg/d; differences vs placebo were statistically significant for cariprazine 3 mg/d, but not for cariprazine 6 mg/d or aripiprazole (P values based on Wilcoxon rank-sum). Differences in PoA change were also statistically significant for both doses of cariprazine vs aripiprazole (cariprazine 3 mg/d, P = .0006; cariprazine 6 mg/d, P = .0260). In patients with a PoA score above or equal to the median PoA at baseline (high cognitive impairment), the difference in median change from baseline to week 6 was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 3 mg/d vs placebo (P = .0080) and vs aripiprazole (P = .0064); differences vs placebo were not significant for cariprazine 6 mg/d (P = .2974) or aripiprazole (P = .4443; Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Change from baseline to week 6 in CDR attention battery. (A) In patients with schizophrenia and high cognitive impairment, the difference in median change from baseline to week 6 was statistically significant in favor of cariprazine 3 mg/d vs placebo and aripiprazole; differences vs placebo were not significant for cariprazine 6 mg/d or aripiprazole. (B) In patients with higher cognitive impairment, median change from baseline to week 6 was significantly higher (improvement) in favor of all treatment groups vs placebo; there were no statistically significant differences between other individual groups.

*P < .05 vs placebo, **P < .01 vs placebo, and †† P < .01 vs aripiprazole. P values based on Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Abbreviations: COA, continuity of attention; NC, no change; PoA, power of attention.

For CoA score in the mITT population, the median (SD) change from baseline to week 6 was 0 (11.7) for placebo, 2 (10.5; P = .0005) for cariprazine 3 mg/d, 1 (14.1; P = .0168) for cariprazine 6 mg/d, and 0 (13.9; P = .1685) for aripiprazole 10 mg/d; differences vs placebo were statistically significant for cariprazine 3 and 6 mg/d, but not for aripiprazole 10 mg/d. In patients with a CoA score below or equal to the median CoA at baseline (higher cognitive impairment), the median change from baseline to week 6 was significantly higher, indicating improvement, in favor of all treatment groups vs placebo (cariprazine 3 mg/d, P = .0012; cariprazine 6 mg/d, P = .0073; aripiprazole, P = .0160); there were no other statistically significant differences between other individual groups (Figure 5B).

Discussion

In multiple post hoc analyses conducted to evaluate the effect of cariprazine on cognitive symptoms, greater improvement was seen across a range of outcomes for cariprazine-treated patients with bipolar I disorder (depressive and manic episodes) and schizophrenia. These post hoc results support earlier evidence of improvement demonstrated in animal models of cognitive impairment Reference Neill, Grayson, Kiss, Gyertyan, Ferguson and Adham 25 , Reference Zimnisky, Chang, Gyertyan, Kiss, Adham and Schmauss 26 and suggest a potential role for cariprazine in treating cognitive symptoms across indications. Given that cognitive dysfunction in serious mental illnesses is associated with decreased quality of life and worse functional outcomes, cognitive symptoms should be considered a critical clinical and therapeutic target for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder.Reference Martinez-Aran and Vieta 16 , Reference Millan, Agid and Brune 51

In patients with bipolar disorder, the pattern of cognitive impairment is broad and heterogenous, with evidence suggesting that cognitive symptoms and depression may amplify each other in producing disability.Reference Miskowiak, Seeberg and Kjaerstad 52 , Reference Depp, Dev and Eyler 53 In these pooled post hoc analyses of data from patients with bipolar depression, greater improvement was observed for cariprazine vs placebo on measures of cognition, depression, and functioning in the overall population and in subsets of patients with greater cognitive symptoms. Since evidence points to a gap between clinical outcomes and functional recovery in patients with bipolar disorder,Reference Martinez-Aran, Vieta and Torrent 54 findings that cariprazine 1.5 mg/d improved cognitive and depressive symptoms as well as functioning in patients with bipolar depression is an interesting clinical outcome. Furthermore, in patients with manic or mixed bipolar I disorder episodes and cognitive symptoms at baseline, significant improvement for cariprazine vs placebo was observed in cognitive symptoms (ie, change from baseline in PANSS Cognitive subscale and on 4 of 5 individual subscale items) as well as in manic symptoms (ie, change in YMRS total score), demonstrating that manic symptom efficacy was not compromised by the presence of baseline cognitive symptoms.

The neurocognitive profile of patients with schizophrenia is characterized by deficits across numerous cognitive domains accompanying general intellectual impairment, which may predate illness onset.Reference Bortolato, Miskowiak, Kohler, Vieta and Carvalho 2 To augment previously published findings reporting subjective cognitive outcomes in cariprazine-treated patients with schizophrenia,Reference Fleischhacker, Galderisi and Laszlovszky 36 , Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 37 post hoc analyses were conducted on data from cariprazine RGH-MD-04, a pivotal trial in which a computerized, performance-based attention battery, the CDR system, was administered.Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 When the PoA factor, an outcome measuring focused attention, and the CoA factor, an outcome measuring sustained attention, were analyzed in the overall ITT population, the difference vs placebo was significant for cariprazine 3 mg/d (P = .0036), but not for cariprazine 6 mg/d or aripiprazole.Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33 When PoA was analyzed in patients with baseline attentional impairment, significantly greater median change from baseline on the PoA was again noted for cariprazine 3 mg/d vs placebo, as well as for cariprazine 3 mg/d vs the active-comparator aripiprazole. As the speed scores from the PoA attentional tasks reflect the intensity of concentration at that particular moment,Reference Wesnes, Caldwell and Wesensten 55 faster responses suggest that more cognitive processes and high levels of effortful concentration were being used. When the CoA factor was examined, significantly greater median change from baseline was seen for both cariprazine 3 and 6 mg/d vs placebo. The CoA reflects the ability to sustain concentration,Reference Wesnes, Caldwell and Wesensten 55 with greater change from baseline suggesting that cariprazine-treated patients were able to sustain focus on a single task for a more prolonged period than placebo-treated patients. Of note, these findings support previous evidence of cognitive symptom improvement in RGH-MD-04, which was shown by statistically significant differences in favor of cariprazine 3 and 6 mg/d vs placebo (P < .001 both doses) in change from baseline on the PANSS Cognitive subscale.Reference Durgam, Cutler and Lu 33

While these CDR system factor results provide an objective assessment of attention in one schizophrenia trial, additional evidence of a treatment effect for cariprazine in cognitive symptoms has been suggested in pooled post hoc analyses of data from the pivotal studies in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia.Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 37 , Reference Fleischhacker, Marder and Lu 56 Namely, statistically significant improvement for cariprazine 1.5 to 9 mg/d vs placebo has been noted in change from baseline to week 6 on various outcomes including PANSS Cognitive subscale (LSMD = −1.47; P < .001),Reference Fleischhacker, Marder and Lu 56 each individual item of the PANSS Cognitive subscale (P < .001 each item),Reference Fleischhacker, Marder and Lu 56 and the PANSS Disorganized Thought factor (LSMD = −2.0; effect size = 0.47; P < .0001).Reference Marder, Fleischhacker and Earley 37 The PANSS 6-item Disorganized Thought factor consists of the Difficulty in Abstract Thinking, Mannerisms and Posturing Disorientation, Poor Attention, Disturbance of Volition, Preoccupation, and Conceptual Disorganization items. Additional evidence of cognitive symptom improvement for cariprazine was also observed in a 26-week study of patients with schizophrenia and persistent, predominant negative symptoms.Reference Fleischhacker, Galderisi and Laszlovszky 36 Of note, differences in change from baseline were statistically significant for cariprazine 4.5 mg/d vs risperidone 4 mg/d (the active-comparator) on both the PANSS Cognitive subscale (LSMD = −0.53; P = .028) and the PANSS Disorganized Thought factor (LSMD = −0.63; P = .05). Since the severity of cognitive dysfunction has been related to psychosis as well as to negative symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder,Reference Zhu, Womer and Leng 57 the favorable findings for cariprazine in cognitive symptom domains in patients with documented negative symptoms may be of particular interest.

Although currently available medications can effectively treat depressive and manic symptom states in bipolar I disorder and psychosis in schizophrenia, evidence of treatment efficacy for illness-related cognitive symptoms is limited, and to date, there is no well-established pharmacologic treatment for cognitive impairment. In addition to cariprazine, preclinical and clinical studies of several other newer atypical antipsychotics (eg, lurasidone, brexpiprazole, and lumateperone) have demonstrated procognitive effects that are likely related to their dopaminergic mechanisms.Reference Corponi, Fabbri and Bitter 58 , Reference Torrisi, Laudani and Contarini 59 A systematic review of studies investigating cognitive enhancement with novel pharmacologic agents (eg, mifepristone, galantamine, and donepezil) in bipolar disorder yielded disappointing or preliminary results without convincing effects.Reference Sole, Jimenez and Torrent 3 , Reference Miskowiak, Carvalho, Vieta and Kessing 60 Furthermore, because cognitive difficulties can persist during periods of euthymia for patients with bipolar I disorder, it is interesting to note that adjunctive lurasidone was more effective than treatment as usual in improving cognition in euthymic patients with reduced cognitive functioning.Reference Yatham, Mackala and Basivireddy 61 In schizophrenia, studies of change in cognitive deficits in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics have been equivocal, with some results suggesting a greater potential for improvement in cognitive symptoms for atypical vs conventional antipsychotic agentsReference Davidson, Galderisi and Weiser 62 , Reference Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer and Zald 63 and others not supporting this finding.Reference Keefe, Bilder and Davis 64 In meta-analyses of prospective clinical studies, atypical antipsychotics were found to have mild effects in cognitive deficits in schizophrenia, with specific atypicals differentially effective within certain cognitive domains.Reference Woodward, Purdon, Meltzer and Zald 63

Although cognitive deficits are a complex problem with a potentially heterogenous etiology, the unique mechanism of action of cariprazine may offer benefits in the treatment of cognition through its activity at the dopamine D3 receptor, which has been identified as a treatment target for cognitive symptoms.Reference Joyce and Millan 65 Unlike other dopamine D2 and D3 dopamine receptor antagonists or partial agonists, cariprazine has a higher potency for the D3 receptor than does dopamine itself, which results D3 receptor blockade.Reference Stahl 66 With almost 10-fold greater affinity for D3 than D2 receptors in vitro,Reference Kiss, Horvath and Nemethy 23 cariprazine also shows high in vivo occupancy at both dopamine D2 and D3 receptors at clinically relevant doses.Reference Girgis, Slifstein and D’Souza 24 , Reference Gyertyan, Kiss and Saghy 67 Cariprazine has demonstrated dopamine D3-dependent procognitive effects in an animal study,Reference Zimnisky, Chang, Gyertyan, Kiss, Adham and Schmauss 26 further suggesting the potential for an efficacy advantage in cognitive symptoms in patients with serious mental illness. Of additional interest, since cariprazine has greater preference for occupying dopamine D3 receptors vs D2 receptors at lower doses,Reference Girgis, Slifstein and D’Souza 24 greater effects for lower doses of cariprazine on cognitive symptoms in both bipolar depression and schizophrenia in our current analyses are consistent with its pharmacologic profile.

These analyses have several limitations including their post hoc nature and lack of adjustment for multiple comparisons, which is typical of post hoc evaluations. Since thorough neuropsychological evaluations were not performed, our findings should be considered relevant to cognitive symptoms, but not necessarily to cognitive deficits or social cognition, which are separate domains that are profoundly impaired in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.Reference Cigliobianco, Paoli and Caletti 68 Because cognition was not a primary outcome in any of the studies and objective measures of cognition were not included in most cases, analyses were based on cognition-relevant rating scale measures that were included in the study protocols. For example, MADRS item 6 (Concentration Item) was used in post hoc analyses of the bipolar depression studies since concentration is considered a subdomain of higher-level cognitive processes (ie, executive function).Reference Harvey 69 As global cognitive functioning requires the coordination and effective use of component cognitive abilities, change in concentration could influence cognitive function, but this item alone is not considered a measure of cognition. Interpretation of some outcomes is limited by the use of rating scale measures that were not specifically designed to investigate cognitive function. Moreover, since cognitive symptoms are closely related to affective and psychotic symptom loads, determining whether treatment effects are attributable to improvement in subjective cognitive function vs overall symptom improvement is difficult. Furthermore, no path analysis was conducted to determine whether improvement in cognition items was independent of improvement in other items and adjustments were not made for common conditions in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, such as obesity, that may affect cognitive outcomes.Reference Bora, McIntyre and Ozerdem 70 , Reference McIntyre, Mansur and Lee 71 The constituent studies were of short duration, there was no objective measure to determine whether cognition was influenced by emotion or was independent of it, and the studies were not designed to detect treatment differences in patient subsets; patients were required to meet stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, which may limit the ability to generalize these results to other bipolar I disorder or schizophrenia populations. Although patient characteristics such as age, sex, age of onset, number of affective or psychotic episodes, comorbid conditions, and concomitant medications may affect cognitive functioning, our analyses did not control for these variables. Differences in the available measures of cognition, doses, and cognitive impairment definitions precluded pooling data across indications for analysis. Finally, the small sample size of some subsets may also reduce the stability and certainty of results.

In conclusion, cariprazine improved cognitive symptoms, function, and performance vs placebo in these exploratory post hoc analyses of patients with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia. Furthermore, the greater improvements vs placebo reported previously for primary outcomes in the original studies (mania measured by YMRS and depression measured by MADRS) were also observed in these post hoc analyses of patient subsets with worse cognitive symptoms. Although manic and depressive symptoms associated with bipolar I disorder and exacerbation of schizophrenia can be well controlled with pharmacologic agents, treatment of cognitive symptoms remains an unmet need in patients with serious mental illness.Reference McIntyre, Berk and Brietzke 72 These analyses provide preliminary evidence, suggesting that cariprazine may have potential benefits on cognitive symptoms in patients with bipolar I disorder and schizophrenia. As such, future prospectively designed acute and long-term trials investigating cariprazine and cognition are warranted.

Additional information

Data inquiries can be submitted at https://www.allerganclinicaltrials.com/en/patient-data/.

Previous presentations

Presented at the American Psychiatric Association (APA) Annual Meeting, May 18-21, 2019; the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology (ACNP) Annual Meeting, December 8-11, 2019; the Neuroscience Education Institute (NEI) Virtual Poster Library, posted online July 2, 2020.

Acknowledgments

Writing and editorial assistance were provided to the authors by Carol Brown, MS, of Prescott Medical Communications Group (Chicago, IL), a contractor of AbbVie. Statistical analysis support was provided by Qing Dong of AbbVie (Madison, NJ).

Financial support

This manuscript was supported by funding from Allergan (prior to its acquisition by AbbVie). The authors had full control of the content and approved the final version. Neither honoraria nor payments were made for authorship.

Disclosures

R.S.M. has received research grant support from CIHR/GACD/National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC); speaker/consultation fees from Lundbeck, Janssen, Alkermes, Mitsubishi Tanabe, Purdue, Pfizer, Otsuka, Takeda, Neurocrine, Sunovion, Bausch Health, Novo Nordisk, Kris, Sanofi, Eisai, Intra-Cellular, NewBridge Pharmaceuticals, AbbVie, Atai Life Sciences. Dr. McIntyre is a CEO of Braxia Scientific Corp. D.G.D. is an employee of Signant Health. E.V. has received grants and served as consultant, advisor, or speaker for: AB-Biotics, Abbott, AbbVie, Angelini, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Farmindustria, Ferrer, Forest Research Institute, Gedeon Richter, Glaxo-Smith-Kline, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Roche, SAGE, Sanofi-Aventis, Servier, Shire, Sunovion, Takeda, the Brain and Behaviour Foundation, the Generalitat de Catalunya (PERIS), the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (CIBERSAM), EU Horizon 2020, and the Stanley Medical Research Institute. I.L. is an employee of Gedeon Richter Plc. P.J.G. is an employee of Signant Health. W.R.E. was an employee of AbbVie at the time of the study, and is a shareholder of AbbVie, AstraZeneca, and Eli Lilly. M.D.P. was an employee of AbbVie at the time of the study and may hold stock.