Introduction

Dementia and cognitive decline are among the greatest public health challenges Mexico will face in the coming years. Mexico's population has quickly aged in the last decades. Mexicans 60 years and older will represent one in every five people by 2030 (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública [INSP], 2014). Meanwhile, the average life expectancy, currently 77, continues to increase to a projected 80 by 2050 (Instituto Nacional de Salud Pública [INSP], 2014; World Health Organization, 2015). This population shift has led to one of the highest rates of dementia in the Americas, currently 30.4 per 1,000 person-years among Mexicans 65 years and older (Prince et al., Reference Prince, Bryce, Albanese, Wimo, Ribeiro and Ferri2013). A better understanding of brain health is needed to reduce the health and financial impact of dementia on individuals, families, and societies (World Health Organization, 2012).

Studies such as the Mexican Health and Aging study show that individual cardiovascular risk factors are associated with cognitive decline and dementia (Mejía-Arango et al., Reference Mejía-Arango, Miguel-Jaimes, Villa, Ruiz-Arregui and Gutiérrez-Robledo2007; Mejia-Arango and Gutierrez, Reference Mejia-Arango and Gutierrez2011; Silvia and Clemente, Reference Silvia and Clemente2011). Cardiovascular risk indices have been associated with cognition among Mexican Americans in the Sacramento Area Latino Study on Aging study and other populations (Yaffe et al., Reference Yaffe, Haan, Blackwell, Cherkasova, Whitmer and West2007; Unverzagt et al., Reference Unverzagt2011; Al Hazzouri et al., Reference Al Hazzouri, Haan, Neuhaus, Pletcher, Peralta and López2013). Health indices of factors that coexist and have a common pathway are promising as they are more comprehensive than single factors (Pearson et al., Reference Pearson2013). However, prevention strategies need to also focus on optimal levels of modifiable health to increase population impact rather than merely on poor levels (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010).

The American Heart Association (AHA) defined a cardiovascular health (CVH) index to track health status in relation to their 2020 strategic goal (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010). This concept includes a set of modifiable cardiovascular risk factors and health behaviors graded either poor, intermediate, or ideal. The AHA's CVH index has been shown to be associated with lower incidence of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and related mortality (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Rundek, Wright, Anwar, Elkind and Sacco2012; Kulshreshtha et al., Reference Kulshreshtha2013). A few studies in the USA have found associations between the AHA's CVH index and cognitive outcomes among people of different ethnic backgrounds (Reis et al., Reference Reis2013; Crichton et al., Reference Crichton, Elias, Davey and Alkerwi2014; Thacker et al., Reference Thacker2014; Gardener et al., Reference Gardener2016; González et al., Reference González2016). For example, one cross-sectional study found positive associations between CVH and scores of cognitive status, verbal learning, phonemic word fluency, and processing speed among USA middle-aged Latinos (González et al., Reference González2016). The Northern Manhattan Study found that in a sample with 65% of mostly Caribbean Latinos, the higher number of ideal CVH metrics was associated with less decline in different cognitive domains (Gardener et al., Reference Gardener2016).

Determining the association between CVH and cognitive function in Mexico is important to promote dementia and cognitive decline prevention and healthy brain aging in this country. Mexico has not just one of the highest rates of dementia in the Americas but also the highest prevalence of diabetes (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Sicree and Zimmet2010), obesity (World Obesity Federation, 2017), and hypertension (Ordúñez et al., Reference Ordúñez, Silva, Rodríguez and Robles2001). Therefore, the aim of this study is to explore the association between an index of ideal levels of modifiable CVH factors and cognitive function among Mexican older adults using nationally representative cross-sectional data. We hypothesize that better levels of CVH will be associated with higher cognitive function. Previous research shows that some CVH components including body mass index (BMI) are associated with dementia in midlife but not later in life (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick2009). This study also aimed to explore whether the association CVH and cognitive function is moderated by age. This analysis builds on prior research in Mexico by using an index of ideal levels of modifiable CVH factors as opposed to individual risk factors or indexes that include non-modifiable factors.

Methods

The current study used cross-sectional data from Wave 1 of the World Health Organization Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE) undertaken in Mexico. This is an observational, longitudinal study representative of the general non-institutionalized adult population (18 years or older).

Sample and procedure

The methodology for SAGE has been published elsewhere (Kowal et al., Reference Kowal2012). In brief, the survey was conducted between 2009 and 2010. A stratified, multi-stage cluster sampling design was used to obtain a nationally representative sample. A probability proportion to size design was used to select clusters. Within each cluster, an enumeration of existing households was done to obtain an accurate measurement of size. As the focus of SAGE was on older adults, individuals aged ≥50 years were oversampled. Interviews were conducted face-to-face at respondent's homes using Paper and Pencil Assisted Interview (PAPI). All the interviewers participated in a training course for the administration of the survey protocol. Quality control procedures were implemented during fieldwork (Üstun et al., Reference Üstun, Chatterji, Mechbal and Murray2005). Those participants who were not able to respond to the survey due to cognitive problems were administered a proxy interview. The individual response rate was 51%. Sampling weights were generated to account for the sampling design. Post-stratification corrections were made to the weights to adjust for the population distribution obtained from the national census and for non-response.

Ethical approvals followed the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki and were obtained from the Institutional Review Board of the National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Mexico. Study procedures for the secondary analysis were supervised by the University of Kansas Medical Center's Institutional Review Board as not involving human subjects research. Written informed consent from each participant was obtained by the National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Mexico. The SAGE dataset is publicly available at the WHO website (http://apps.who.int/healthinfo/systems/surveydata/index.php/catalog/sage).

Measures

Cognitive function

Cognitive function was assessed using performance Spanish language measures of immediate and delayed verbal recall, verbal fluency, and forward and backward digit span. Verbal memory was tested using the Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease verbal recall test, consisting of three repetitions of a ten-word list for immediate recall with scores ranging from 0 to 30 words recalled correctly, and then assessing the recall of these words after a 10-minute delay with scores ranging from 0 to 10 words recalled correctly (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Mohs, Rogers, Fillenbaum and Heyman1988). The verbal fluency test consisted of naming as many animals as possible in 1 minute with scores being the sum of different words correctly named (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Mohs, Rogers, Fillenbaum and Heyman1988). Digit span was used to assess memory capacity and executive function, using both forward and backward digit recall tests (Wechsler et al., Reference Wechsler, Coalson and Raiford1997). The forward digit span version contained nine and the backward version eight series. Each series had two trials. The score in each digit span task was the series number in the longest series repeated without error in the first or second trial. An overall cognitive function score was calculated by averaging the standardized scores of each test. All cognitive tests have been validated in the Mexican population (Ostrosky-Solís et al., Reference Ostrosky-Solís, Ardila and Rosselli1999; Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2001; Tulsky and Zhu, Reference Tulsky and Zhu2003; Escobedo and Hollingworth, Reference Escobedo and Hollingworth2009; Sosa et al., Reference Sosa2009). The score in each digit span task was the series number in the longest series repeated without error in the first or second trial. An overall cognitive function score was calculated by averaging the standardized scores of each test.

Cardiovascular health index

We obtained the CVH indices following four of the seven criteria from the AHA definition (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010). Full data on the remaining three criteria (fasting cholesterol, glucose, and diet) was not collected in the survey, and therefore was not included in the composite measures. All participants were asked whether they had ever used tobacco. Participants who had used tobacco were asked whether they currently used it daily, non-daily, or not at all. Those who reported former tobacco use were asked how old they were when they stopped using tobacco. Participants who had never smoked or quit more than 12 months before the survey were considered to have ideal smoking status in that criterion. Those who were current smokers or quit within the last 12 months were considered to have poor/intermediate smoking status. The Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) was used to measure the intensity, duration, and frequency of physical activity in three domains: occupational; transport-related; and discretionary or leisure time (Bull et al., Reference Bull, Maslin and Armstrong2009). The Spanish GPAQ has been validated among an almost fully Mexico-born sample in California (Hoos et al., Reference Hoos, Espinoza, Marshall and Arredondo2012). The total time spent in physical activity during a typical week, including the number of days and intensity, were used to generate categories of ideal physical activity levels (≥150 minutes per week of moderate intensity, ≥75 minutes per week of vigorous intensity, or a combination of both) and poor/intermediate levels (0–149 minutes per week of moderate intensity, 0–74 minutes per week of vigorous intensity or a combination of both). Weight and height were measured to calculate BMI, calculated as weight/height2 (kg/m2). Participants with a BMI <25 kg/m2 were considered to have ideal BMI levels and those with higher BMI were considered to have poor/immediate levels. Blood pressure was measured three times on the right arm of the seated respondent using a wrist blood pressure monitor. Out of three measurements, an average of the first two measurements was used as the blood pressure value in this analysis. Participants with systolic values <120 and diastolic values <80 mmHg were considered to have ideal blood pressure levels. Those with either systolic or diastolic blood pressure levels than ideal were considered to have poor/immediate levels. The four criteria for ideal CVH are in line with the Mexican national guidelines for tobacco use, physical activity, BMI, and blood pressure (Secretaría de Salud, 1999, 2009; Bonvecchio et al., Reference Bonvecchio, Fernández-Gaxiola, Plazas, Kaufer-Horwitz, Pérez and Rivera2015). Participants obtained a score of 1 if they met the ideal criterion for each component (smoking, physical activity, BMI, and blood pressure) and a 0 otherwise, with total score ranging from 0 to 4 points (Table 1). We used two definitions of CVH, first as a continuous variable and second as a categorical variable with five groups (0, 1, 2, 3, and 4). Secondary analyses examined the moderating effect of age (50–64 years and 65+ years) in the association between CVH and cognitive function and the association of cognition with each of the CVH components individually.

Table 1. Criteria for ideal or poor/intermediate levels of cardiovascular health of individual factors according to the index

Covariates

Socio-demographic information included age (continuous), gender, years of education (continuous), wealth (continuous), and urbanicity (rural/urban). For wealth, a multi-step process was used where asset ownership was first converted to an asset ladder, and then the Bayesian post-estimation method was used to generate raw continuous income estimates. Urbanicity was defined consistently with the way the areas were legally proclaimed to be, including towns, cities and metropolitan areas (urban), commercial farms, small settlements, rural villages, and areas further away from towns and cities (rural).

Statistical methods

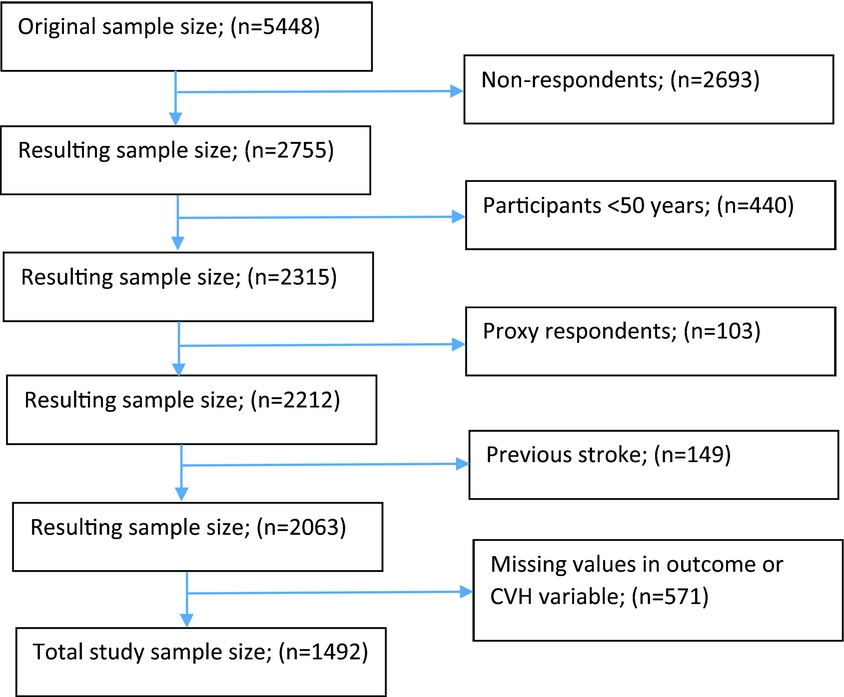

The analysis was restricted to participants aged ≥50 years. Proxy respondent data was not included as they did not provide information on key variables. Participants with stroke assessed through either an algorithm or self-report of diagnosis were excluded from the sample as the association of CVH and stroke is well established (Dong et al., Reference Dong, Rundek, Wright, Anwar, Elkind and Sacco2012; Kulshreshtha et al., Reference Kulshreshtha2013). Descriptive analyses included weighted percentages, unweighted frequencies, means, and standard errors. Models controlled for age, gender, education, wealth, and urbanicity. Interaction analysis was conducted to assess the moderating effect of age. Cross-sectional analyses were conducted using linear regression. The level for statistical significance for all analyses was set at p < 0.05. Complete case analysis was conducted. Figure 1 shows a flowchart with information on how the final sample was reached. Participants deleted based on missing values in CVH or cognitive function (n = 571) did not differ statistically from those not missing in age, gender, education, wealth, and urbanicity. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 using complex samples analysis (IBM Corp. Released, 2013).

Figure 1. Sample flowchart and reasons for exclusion.

Results

Among the 1,492 participants included in this analysis, the mean age was 61.6 years, ranging from 50 to 93 years and 53.6% were women. The average years of education was 5.1 and 21.6% lived in a rural setting (see Table 2). Socio-demographic factors were not associated with CVH. CVH was worst (score 0) for 8.4%, and best (score 4) for 2.2%.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of SAGE participants aged 50 years and over by cardiovascular health (CVH)

Table 3 shows the bivariate and multivariate linear regressions of global cognitive function with the continuous and categorical CVH indices and covariates. The continuous CVH index was not associated with cognitive function in either the bivariate or multivariate models. Regarding the 0–4 categorical CVH index, in the bivariate linear regression, participants with the best levels of CVH (score 4) had cognitive function scores 0.47 SD higher than those with a score of 2 (p < 0.05). After controlling for covariates, participants with best CVH (score 4) had higher cognitive function scores than those with a CVH score of 0 (0.41 SD), 1 (0.39 SD), and 2 (0.56 SD; p < 0.05 for all differences). The interaction between CVH and age group was statistically significant (p < 0.001). The association between CVH and cognitive function was only present among participants 50–64 years old in which best CVH (score 4) was associated with higher cognitive function scores compared to CVH scores of 0 (0.56 SD), 1 (0.49 SD), 2 (0.68 SD), and 3 (0.42 SD; p < 0.05 for all differences).

Table 3. Relationship of continuous and categorical indices of CVH and covariates with global cognitive function in the total sample and by age group

a Bivariate associations between each of the variables in the column and global cognitive function independently.

b Multivariate models control for all the gender, age, education, wealth, and urbanicity.

c Multivariate models control for all the gender, education, wealth, and urbanicity. Data are β’s (95% CI) for global cognitive function z scores. REF: reference category. Statistically significant associations at the 0.05 level are marked in bold.

Table 4 shows the bivariate and multivariate associations of global cognitive function with the individual CVH factors (smoking, exercise, BMI, and blood pressure). Poor/intermediate levels of smoking were associated with 0.33 SD higher of cognitive function compared to ideal levels in bivariate and 0.17 SD in multivariate associations (p < 0.05 each). In bivariate associations, ideal levels of exercise were associated with 0.17 SD higher of cognitive function than poor/intermediate levels, but the association disappeared after controlling for covariates. BMI was not associated with cognitive function in either model. Ideal blood pressure levels were associated with 0.29 SD higher of cognitive function compared to poor/intermediate levels in the bivariate model and 0.27 SD in the multivariate model.

Table 4. Relationship of individual CVH factors with global cognitive function

a Bivariate associations between each of the variables in the column and global cognitive function independently.

b Multivariate models control for all the gender, age, education, wealth, and urbanicity. Data are β’s (95% CI) for global cognitive functionz scores. REF: reference category. Statistically significant associations at the 0.05 level are marked in bold.

Discussion

This study has examined the cross-sectional association between an index of ideal levels of modifiable CVH factors and cognitive function among a representative sample of Mexican older adults. Findings suggest that CVH is positively but non-linearly associated with cognitive function in this population. In particular, participants with the best levels of CVH have higher cognitive function than those at lower levels. These associations are modified by age and are only present among people aged 50–64 years but not older.

The present study adds to the growing evidence that CVH is important for cognitive function (Reis et al., Reference Reis2013; Crichton et al., Reference Crichton, Elias, Davey and Alkerwi2014; Thacker et al., Reference Thacker2014; Gardener et al., Reference Gardener2016; González et al., Reference González2016). The exclusion of participants with stroke suggests that there might be alternative vascular mechanisms for cognitive impairment other than stroke (Kulshreshtha et al., Reference Kulshreshtha2013). Contrary to findings from some previous studies using the AHA definition of CVH, we found that only the best levels of CVH were associated with substantially higher cognitive function. This data contrasts with linear cross-sectional associations found among Latinos aged 45–74 years, and longitudinal associations in the general population aged 18–30 years in the USA (Reis et al., Reference Reis2013; González et al., Reference González2016). The results also contrast with a longitudinal study among Americans 45 years and older that found that cognitive impairment was highest for those with poor CVH but the same for those with intermediate and high levels of CVH (Thacker et al., Reference Thacker2014). In our study, however, CVH was measured using only four out of the seven AHA components of CVH, making comparisons with other studies different. We also found that the association between the categorical index of CVH and cognitive function was stronger than associations with individual CVH components. This finding supports the idea that dementia prevention trials should focus on multiple cardiovascular risk reduction (Olanrewaju et al., Reference Olanrewaju, Clare, Barnes and Brayne2015). These results are also in line with the AHA notion that prevention should not merely focus on preventing poor CVH levels but also promote optimal levels (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010).

These results are the first attempt to examine the association between an AHA-like index of ideal levels of modifiable CVH factors and cognitive function in the Mexican population. The importance of using an AHA-like approach of CVH relies upon including biomarkers and behaviors that are modifiable and account for optimal levels of CVH (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010). Therefore, the index used in the present study has more direct implications for health promotion and disease prevention than studies assessing the association with single factors, (Biessels et al., Reference Biessels, Staekenborg, Brunner, Brayne and Scheltens2006; Cataldo et al., Reference Cataldo, Prochaska and Glantz2010; Bherer et al., Reference Bherer, Erickson and Liu-Ambrose2013) examining solely poor levels of CVH (Biessels et al., Reference Biessels, Staekenborg, Brunner, Brayne and Scheltens2006; Reitz et al., Reference Reitz, Tang, Manly, Mayeux and Luchsinger2007) or including non-modifiable components (Unverzagt et al., Reference Unverzagt2011).

This study shows that the association between CVH and cognitive function is only present among participants 50 – 64 years old. These findings are consistent with the literature as for example, BMI in midlife has been shown to be associated with dementia and cognitive function in later life, whereas BMI measured later in life has an inverse association with cognitive impairment (Fitzpatrick et al., Reference Fitzpatrick2009). Similarly, midlife hypertension has been shown to be an important modifiable risk factor for late life cognitive decline and dementia (Whitmer et al., Reference Whitmer, Sidney, Selby, Johnston and Yaffe2005). However, the association in older ages remains unclear (Verghese et al., Reference Verghese, Lipton, Hall, Kuslansky and Katz2003; Kloppenborg et al., Reference Kloppenborg, Van Den Berg, Kappelle and Biessels2008). This study therefore adds to the evidence on the importance of timing and supports the idea that midlife may be a critical period for conducting CVH interventions to reduce dementia risk (Kloppenborg et al., Reference Kloppenborg, Van Den Berg, Kappelle and Biessels2008; Gorelick et al., Reference Gorelick2011).

Findings from this study may also apply to many older adults living in the USA. In fact, a higher AHA CVH index score was cross-sectionally associated with better cognitive function among USA Latinos of whom 33.4% were of Mexican descent (González et al., Reference González2016). Currently, 34% of the 33.7 million Mexican Americans are Mexico-born (Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez, Reference Gonzalez-Barrera and Lopez2013). Mexican Americans might share cultural and genetic characteristics related to CVH with the Mexican population, especially first generation ones. However, studies also suggest that the adaptation of Mexican Americans to the USA dominant culture might put them at a higher risk of dementia, as their risk of obesity, diabetes, sedentary lifestyle and smoking increases with the number of years lived in the USA (Goel et al., Reference Goel, Mccarthy, Phillips and Wee2004; Caballero, Reference Caballero2005; Kondo et al., Reference Kondo, Rossi, Schwartz, Zamboanga and Scalf2016). Generalizability of these findings to Mexican Americans may be threatened due to the Hispanic paradox in which there is a positive selection of immigrants from Mexico to the USA from the general population (Markides and Eschbach, Reference Markides and Eschbach2005).

There are limitations to this study. First, the study lacked data on nutrition, glucose levels and cholesterol and therefore could not replicate the AHA definition of CVH (Lloyd-Jones et al., Reference Lloyd-Jones2010). Differences found between this and other studies using the AHA definition of CVH may be related to the incomplete composite score. Second, the CVH index has not been previously validated in the Mexican population. Third, the assessment of CVH gives the same weight to the different domains, which might not represent their real contribution. Fourth, this study is cross-sectional, and therefore, causality cannot be inferred from the associations. In fact, associations such as the one between smoking and higher cognitive function have been shown to be an artifact of cross-sectional data, whereas longitudinal data shows associations in the opposite direction (Cataldo et al., Reference Cataldo, Prochaska and Glantz2010). Fifth, urbanicity was predefined according to the way the areas were legally proclaimed to be, which ignores the participants’ urban or rural migrations. However, 90.6% of the sample had lived in the same locality either always or most of their adult lives adding little information to the predefined urbanicity variable. Finally, the lower response rate (51%) may increase the risk of selection bias. Regarding potential public health implications, this study highlights the importance of optimal levels of CVH, especially in midlife as a potential means to improve brain health among Mexican older adults. If results are confirmed with longitudinal data, this will mean that greater effort needs to be made to prevent cognitive decline by promoting optimal levels of CVH as a whole as the current prevalence of best CVH levels is 2.2%. Comprehensive worksite wellness programs targeting weight, physical activity, blood pressure, and tobacco use might be optimal given that most Mexicans 50–64 years old are working and spend a significant part of their day at work. Workplace interventions have the potential to have economic and productivity benefits to employers in addition to health improvements (Baicker et al., Reference Baicker, Cutler and Song2010). These interventions will work best if paired with improvements in other evidence-based population CVH strategies, including media and educational campaigns, labeling and consumer information, taxation, subsidies, and other economic incentives, local environmental changes, direct restrictions, and mandates (Mozaffarian et al., Reference Mozaffarian2012).

Conclusion

These findings add to the growing evidence that CVH is an important factor for cognitive health and is the first study in Mexico to address this association using an index of ideal levels of modifiable CVH factors. We found that the best levels of CVH were associated with higher cognitive function compared to other levels among stroke-free Mexican older adults. These results suggest that dementia-related policies in Mexico need to focus on optimizing CVH as a whole rather than simply preventing poor levels of isolated CVH factors. These findings also suggest that improving CVH at midlife might be more beneficial for cognitive function than later in life. Future research is needed as CVH might be a key to slow down the devastating health and financial dementia consequences affecting individuals, families, and societies in Mexico.

Conflict of interest

None.

Description of authors’ roles

J. Perales was involved in the conception and design of the work and carried out the analysis. J. Perales, L. Hinton, J. Burns, and E. Vidoni were involved in the interpretation of data. The first version of the manuscript was written by J. Perales and was subsequently improved by L. Hinton, J. Burns, and E. Vidoni with important intellectual contributions. All authors have approved the final version.

Acknowledgments

JP is thankful to the SAGE teams in Mexico and the World Health Organization. He is also grateful for the chance to attend the Mexico capacity building sessions granted by his former team at the Parc Sanitari Sant Joan de Déu, Barcelona and funded by the European Commission and the Instituto Carlos III through the COURAGE in Europe project. This study was supported by the World Health Organization and the US National Institute on Aging through Interagency Agreements (OGHA 04034785; YA1323-08-CN-0020; Y1-AG-1005-01) and through a research grant (R01-AG034479). Research reported in this publication was also supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P30AG035982. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.